Emmanuel Gatti, Grotte. Gravure, morsure directe sur trame d’aquatinte, 25 ex., 70x100.

What the Proposed Predappio Museum Can Learn from the Piana delle Orme Collection

Predappio, the little town in the Emilia-Romagna region where Mussolini was born in 1883, made the news and generated some controversy in 2016, when it announced plans for a museum on the subject of fascism, to be housed inside the town’s outsized former Fascist Party headquarters building (the casa del fascio), which towers over its only piazza1.

Press outlets have been interested in sensationalizing the project – the Washington Post falsely announcing, most entertainingly, that the displays would be shaped like the rings of the Inferno with Mussolini at their center2. Scholarly circles (including Passés Futurs), however, have seized the chance for long-overdue debates about the representability of Italian fascism for Italian museum audiences, whether in Predappio or elsewhere. Both opposition to and support for the planned museum and its location have been articulated3. In response, the project’s advocates have posted the 500-page project on line, for all to study4.

Those in favor point out, rightly, that no such museum exists anywhere in Italy yet – implying that this one therefore should. (This is a remarkable thing indeed, and worth paying attention to: Italy has no mainstream national, government-sanctioned representation of the fascist era, or of World War II. Why not? What does this imply, and what are the consequences?) But given that this is so, the antagonists reply, why should the first museum of its kind be in Predappio, a very small, remote town of just over 6,000 people that is tainted with the pro-fascist sentiment of tens of thousands of visitors per year to the house of Mussolini’s birth and the crypt holding his remains, who buy fascist and neo-fascist souvenirs from the shops along the town’s main drag, and chant fascist slogans and perform the fascist salute in public? Predappio is the epicenter of today’s continuing cult of Mussolini: doesn’t that make it, they argue, the least appropriate place for a museum dedicated to serious impartial study of fascism?

This and the other back-and-forths5, however, have neglected the most essential aspect of all. If Predappio creates such a museum – or if any museum of its kind is created anywhere in Italy – how will it depict Mussolini? What will its displays convey about how to regard him? What will it tell visitors about how to evaluate the dictator’s cult – then, and more urgently, today? A museum that takes no position on these questions (which is the case of the projected Predappio museum, judging from its published documentation) may be innovative because its topic is unprecedented. But it will add nothing to the landscape of ambivalence about the regime that Italians already possess; it will be, in short, pointless.6

Museal Contexts

The planners of the Predappio museum would certainly strengthen their case if they presented their project within a broader context of museums portraying extreme-right movements and governments, to clarify the intended contribution of their own museum. Several critics rightly note the necessity of discussing the project in relation to existing museum and documentation-center displays in Germany7, the most obvious comparanda for Predappio’s proposal. Even so, none have specified the qualitative, narratological decisions made in the assembly of the German displays – which, after all, are the best reason for comparing an Italian project to the German museums already in existence.

Before describing German displays, it must be said that depictions in other western European museums, and American ones, concerning World War II regularly include large images of Hitler, and amplified recordings of his speeches. These are staples of the representations at museums designed to be didactic, such as France’s (superlative) Mémorial de Caen-Normandie. The purpose, of course, is to impress upon the visitor the hypnotic power of Nazi Germany’s dictator – the enemy of the British, the anti-Vichy French, the Dutch, and so on – and give an experiential feel of the terror of the era for Germany’s victims, while also underscoring the heroic courage of those who resisted.

In contrast, in Germany’s national history museum (the Deutsches Historisches Museum, in Berlin) the only “experience” one can have of Hitler is by standing in one spot, under a small audio projection cone, and facing a video clip that is projected on a very small scale. Because it is so reduced and the viewer-listener must stand in a precise location, not even two people can fully take in the combined audio and video recordings simultaneously, which limits the effect and prevents group sensations that could foster cultic sentiment. More generally, the documentation throughout this portion of the museum is extremely detailed regarding German citizens, as individuals and as groups: as participants with agency in the story of National Socialism. The entire exhibition program squarely places responsibility on society’s shoulders, without overstating Hitler’s individual charisma or power. In this official national historiographic narrative no one is exculpated, and no single individual had the power to sway millions of others.

Munich’s Documentation Center for the History of National Socialism (NS Dokuzentrum) is more locally focused, on how Munich’s pillars of society supported Hitler early on – and by implication, how without their local support, he likely would never have attained national office in 1933. Here too, we see little of Hitler and a great deal of “ordinary” citizens and their interests. But in this case, the site also plays an important part, in a way that is relevant to the Predappio project: the Center, a new building, stands on the plot of land previously occupied by the Brown House (Braunes Haus), the National Socialist Party’s first headquarters. That building did not survive the war, and the empty lot had stood vacant up until the construction of the Documentation Center, which opened in 2015. Replacing this history-laden structure with the Center, even after such a long time, and simultaneously filling anew a site that still held cultic potential, was a judicious decision about the site itself. Predappio’s Fascist Party headquarters is not nearly so auratic, of course – one has to look to Milan for the sites of Mussolini’s earliest successes – but this is one idea Predappio’s planners might want to consider: changing the architectural container, i.e. replacing the old casa del fascio with a new building that is free of fascist history, in order to present their historical expositions more neutrally.

Predappio planners could also examine the sorts of museums that already exist in Italy and are relevant to their own project. Although there is no national Italian museum portraying fascism, Mussolini, or World War II – in fact, any period past the Risorgimento and Unification (unless, as in Rome’s Museo centrale del Risorgimento al Vittoriano, it follows from Unification) – there are many local museums, municipal or private, adding up to an uncoordinated, incomplete jigsaw puzzle of historical depiction across the country. The undeniably philo-fascist ones call themselves “study centers” rather than museums, acknowledging Italy’s (regrettably limited) law forbidding “the apologia of fascism”, the Scelba Law of 1952. Countless collections concerning fascism and the War dot the land, in any case, aiming to portray historical events through a local lens. Among the best are Catania’s museum narrating how World War II unfolded in Sicily in 1943, with the Allies’ landing and combat between Nazi and Allied forces (Museo storico dello sbarco in Sicilia 1943); and the Museum of the End of the War (Museo della fine della Guerra) in Dongo.

The museum in Catania foregrounds the war as experienced by Sicilians and to some degree, by the troops and military medical personnel: those who experienced it on the ground. We do encounter the national leaders who made decisions in the war, but only after depictions of uniforms, materiel, and the locations of clashes in Sicily. They take the form of a series of life-size wax figures: Hitler, alone; Churchill and Roosevelt, who are together; and Mussolini with King Victor Emmanuel III, also together. In each case, the figures are behind glass and identified only briefly by name, without historical explanations as to their roles. They are all presented standing or sitting still, neither gesturing nor speaking. It is impossible to “make” eye contact with them, as one so often can in wax-figure displays; instead, within their glass enclosures they gaze not at each other but in different directions, (as do Mussolini and the King), or outward and over our heads (as Hitler does). There is no way for a visitor to derive any “charge” of illusory interaction with any of them. The scenes of battlefield medical care and radio operations, on the other hand, are in the open, not behind glass, and their figures are in action. Mussolini’s role in bringing Italy into the war is noted in the introductory narration, but his persona as dictator is entirely absent (unlike Hitler’s, whose wax figure is accompanied by a copy of his Mein Kampf).

Dongo’s museum is situated on the shore of Lake Como, at almost the exact spot where anti-fascist forces caught Mussolini and his retinue as they fled in disguise for the Swiss border on 27 April 1945 (they killed Mussolini the next day, alongside his mistress Claretta Petacci). The exhibition consists in a few small rooms, beginning with one using archival newspapers and audio recordings to put visitors in the historical moment, when everyone knew the war was on the verge of ending, but no one knew how it would end. The next room further places the visitor in the time of Mussolini’s capture by illuminating a few evocative objects (a typewriter, a rifle, a steamer trunk, a bust of Mussolini collapsed on its ear, all with a voiceover annotation), set behind a sheet of Mylar. A few seconds of footage, filmed just after the capture, are then projected over this display. Mussolini’s features are drawn, he is haggard: a dead man walking, as we know. Does he?, we have a chance to wonder. Footage of his mutilated corpse being suspended for display in Milan’s Piazzale Loreto follows, showing the jeering, festive throngs that witnessed the dictator’s ignominious end. Although a few more displays show the tension between Right and Left in the Como region at the time, and offer oral-historical clips of locals recalling how they experienced the events, it is the museum’s limited scale and precise emphasis on this moment, in this place, that make it successful. The museum is much more about the historical tipping point that happens to have occurred here, than it is about Mussolini himself – once again, leaving the fascist leader unexplained.

Piana delle Orme, Borgo Faiti (LT), Lazio

But no museum I know of matches the scale or narrative ambition of the Piana delle Orme collection in the Agro pontino area south of Rome (Pontine Marshes, in English). The area is best known for the fact that Mussolini’s regime completed its most ambitious land-reclamation project there in the 1930s, creating a drainage system for the plain’s 300 square miles that is still maintained today, making the land arable for the first time in centuries, and settling roughly 3,000 large farmer-families imported from Italy’s northeastern regions8.

Set in a large park surrounded by the Agro pontino’s farmland, the Piana delle Orme (literally, Plain of Footprints, meaning, Plain of the Traces of Our Ancestors) is the creation of Mariano De Pasquale (1938-2006), who had migrated from Sicily to the Agro pontino as a teenager in 1955 (his grandfather had bought land there in 1954) and prospered in the flower-growing business, while accumulating his personal collection of objects and machines related to the Agro pontino – as an agricultural area before and after reclamation, and as an area deeply marked by World War II.

The museum opened in 1997, and I interviewed De Pasquale in 2000, when I first visited. He described how the museum had grown directly from his collection, which itself was shaped by his love of machines – machines of war and of farming alike9. Museum Director Alda Dalzini has been in charge of shaping the assembly and display of the collection from the beginning. The Piana’s guidebook, published in 2015, credits her with the entire shape of the museum – its “organization, exhibition criteria, and development, making it increasingly prestigious and rigorous”10. In Dalzini’s own preface to the Piana’s guidebook, though, she emphasizes that she is a historian without professional training as such. In her words, the team that developed the museum, herself included, consisted of

autodidacts who [had] dispensed with the participation of “experts”, who in De Pasquale’s opinion, were likely to derail his idea of a museum. … Mariano wanted… a place that would be experienced and shared, not a cemetery or a mere container for dead things; a place where the central, dominant element wouldn’t be his collection, but the people who came to visit it. This was the hardest part, making the museum “alive”, evocative, empathetic, interactive… it was … complicated to get people to understand that the museum was neither a temple nor a site of celebration, or for that matter, a place for the élite or for experts11.

De Pasquale had said similar things to me in our interview fifteen years earlier. When I asked what his preferred sources were and whether he read the work of local authors or national ones, he explained that he was not a reader (non leggo), but that in the evenings he watched documentaries (filmati) and he was confident that the history depicted in the Piana narration was “fair” (giusta). As the rest of this section describes, the Piana’s history is largely a “people’s history” rather than a top-down one – we might say a public history, even though De Pasquale and his team have not.

De Pasquale told me firmly that he had no intention of making a political statement with his collection. Yet when I asked if it was possible to separate the Agro pontino’s development and prosperity from its fascist-regime origins, he conceded that No, only a totalitarian regime would have the latitude to carry such an extensive project to term so quickly and efficiently. As for the museum’s displays, while they are never overtly political, we can read some political positions into them nonetheless – but even if we do, the upshot is an ambiguous one. Aside from a few political-historical explanations, rather than political positions or objectives the museum consistently emphasizes the material conditions shaping the everyday lives of everyday Italians – who were, by implication, uninformed and unaccountable.

Piana delle Orme: Narrative overview

The layout of De Pasquale’s huge collection in the Piana is idiosyncratic, but it makes sense if we understand that it is organized almost entirely around machinery – machinery such as tractors that both destroy the beauties of pre-industrial rural life, and make organized agriculture, and thus prosperity, attainable – as well as the strictly-destructive machinery of war, including armored tanks12. The collection is distributed along carefully arranged paths winding through over a dozen barracks, which are arranged in two rows. Between the rows stand two original airplanes. Inside the barracks, parts of the collection are arranged in a narrative, and others around a theme; some spaces simply display whole sets, such as the ones devoted to tractors, or toy airplanes. In some of the displays, a short audio commentary is available at the press of a button, and in many areas posterboards provide historical and photographic context, but there is no guide to whom one can pose questions.13

The narrative arc begins with dioramic life-size scenes of the Pontine Marshes prior to Mussolini’s reclamation (bonifica) of the 1930s. The walls are painted with landscape backdrops, and life-size figures stand closer to us. Everything is designed to immerse the visitor, initially, in a technologically primitive, if bucolic, existence: we walk through a reconstructed lestra, the grass-roofed hut built by the area’s few residents in the days when the area was still extremely malarial. Inside it is a thorough array of the pre-industrial tools of subsistence, for hunting, carving, tanning, and so on, that were in use here up to the land reclamation of the 1930s. The scene exudes an air of nostalgia, thanks to the soundtrack that accompanies visitors through this and the following scenes, which combines portions of Mascagni and Massenet with others commissioned by De Pasquale: by turn sweeping, caressing, and sentimental, it guides our experience and makes clear the inspiring tone De Pasquale intended to set. We walk through to scenes of the massive reclamation, and end up in a post-reclamation Agro pontino area, with neatly lined up farmhouses and men deployed across fields astride tractors, while women pump water in their house courtyards.

At this point the exhibition interrupts its diachronic progression and we walk through an immense space filled with tractors and other farm equipment. We visit various rooms showing the production and storage of olive oil and wine. Suddenly, we will be catapulted away from the Agro pontino into other scenes in Italy, all of which we can assemble under the label “vernacular”. In this regard the Piana delle Orme celebrates the rural life, the mountain life, the non-urban life. It even hints at De Pasquale’s own experience of internal migration in the 1950s, in the form of a bus getting ready to leave a small Sicilian village, in which all the shops are permanently closed, according to signs on their doors, for lack of business.

We soon enter the second phase of the narrative arc: World War II. The drama of the Allied landings at Anzio, which is nearby, is rendered with simulations of nighttime machine gun exchange, and dioramas show how the towns and houses of the Agro pontino built in the 1930s were damaged in the long standoff between Nazi and Allied forces. We also walk through recreations of troops on the move in the North African theater of war. The war narration climaxes when we enter a grand space simulating the freshly ruined Monastery of Monte Cassino – which is nearby as well.

Piana delle Orme: Mussolini

More than anywhere else in Italy, in the Agro pontino Mussolini played the role of driver of agricultural development; locally, he is remembered especially positively in this capacity14. The Piana delle Orme represents him twice in this persona, operating machines of agricultural production – in keeping with the image he cultivated as a demiurgic, life-giving sometimes-farmer. In the first instance here, he is part of the display of a tractor, one he posed on when in 1936 he officially founded the town of Aprilia, the fourth town (of five) the regime built in the Agro pontino.

Piana delle orme: Mussolini and the make of FIAT tractor he used in the ritual founding of Aprilia, April 1936.

The second time Mussolini appears he is not identified, and yet his identity is unambiguous given his appearances in the Agro pontino during harvest days. We see him on top of a threshing machine – the same model of red ORSI threshing machine that he sat on top of for a few hours, in July 1934.

Mussolini (unidentified) on ORSI thresher in Piana delle Orme.

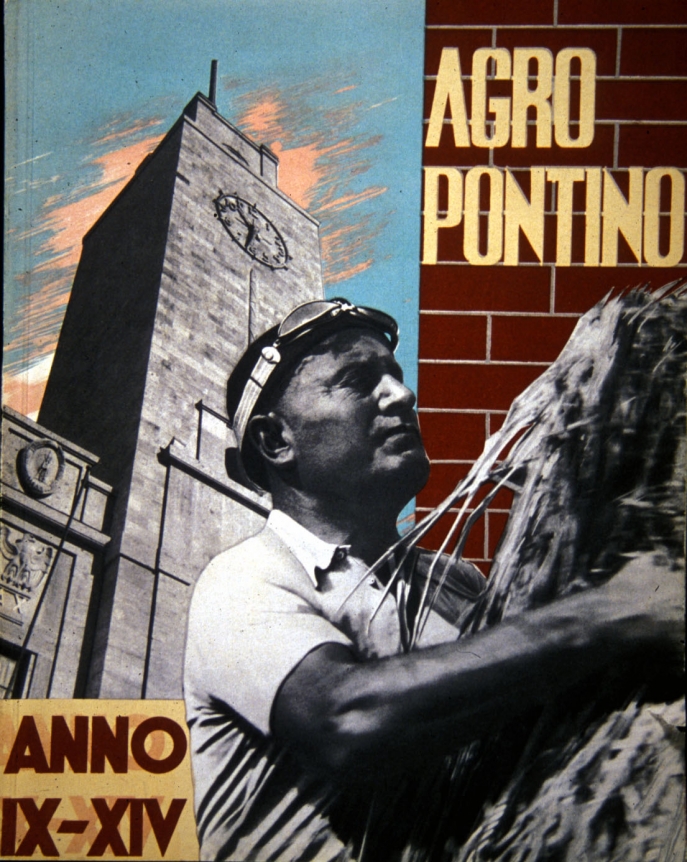

Snapshots of Mussolini’s harvest participation were widely circulated in the 1930s – and images of this same day, when he wore a white shirt, reappeared in paintings and on magazine covers.

Mussolini on ORSI thresher on 9 July 1934, collage on cover of propaganda volume.

Here, though, this is a local image, so we can hardly interpret it as nothing more than a straightforward piece of pro-Mussolini propaganda: it is also a specific reference to a historical event that persists in the settlers’ descendants’ collective memory. The display itself offers no fanfare; most non-local visitors are unlikely to recognize the reference to Mussolini, and in fact, I have never seen anyone even recognize the figure on the thresher as the dictator.

Piana delle Orme: Politics

It would be far beyond our scope to examine all the political uncertainties of the Piana’s historical representations, but I will detail three of them to underscore that while the history offered here is responsible-enough, it also leaves out divisive issues and maintains ample room for visitors to learn nothing new, instead being reminded of rather comfortable, partial narratives about the fascist regime, World War II, and Italy’s Empire – or of nothing, as is the case of the still unresolved civil war of 1943-4515, which is unmentioned.

One poignant display, including a vintage train and boxcars, depicts deportations of Jews and other prisoners from an Italian train station. Long texts on posterboards on the way to the platform do mention Italian concentrations of prisoners that took place before Italy’s surrender in the war in September 1943 and the Nazis’ subsequent aim to deport all of Italy’s Jews to extermination and concentration camps elsewhere – but only briefly. Far more space is devoted to the experiences of Italian prisoners of war in German camps, later in the war. But the physical display itself, which is the only thing most visitors will scrutinize, clearly takes place after October 1943: on this platform, Italians did not persecute other Italians. They were the victims, and their victimizers were outsiders.

The second key scene shows an unnamed figure leaving Rome for Bari. For the initiated, of course, this illustrates King Victor Emmanuel III’s abandonment of his post in Rome in September 1943 along with Marshall Pietro Badoglio. While he sits in the back of his chauffeur-driven car, figures by the side of the road till orti di guerra (as a sign designates them) – wartime agricultural fields – in order to survive. But there will be no references to Rodolfo Graziani, to the Repubblica Sociale Italiana, or to complicities between Italian fascists and Nazi forces in the wake of the King’s departure. And for the uninitiated, the meaning of the scene will remain opaque altogether.

Finally, another scene – again, only recognizable to those who already know the story – shows men in SS Gestapo uniform directing evacuations of the settlers in the Agro pontino plain, to higher ground. The German troops retreating northward in 1944 had broken the area’s pumps to re-flood the Agro pontino plain (which even now, requires pumps to keep it dry and habitable), slowing their enemy’s progress. There is an inconclusive debate as to whether the Germans were perpetrating a deliberate biological crime of war by knowingly increasing the level of malaria, which inevitably followed the rising water level they caused. While there is a strong case made by historian Frank Snowden that they were16, locals I have interviewed always say, “but the Germans evacuated us!” – effectively absolving the Nazis of having caused the disaster from which they, the inhabitants, needed to be evacuated. Remarkably, the Piana delle Orme’s own signage provides two different narratives: one posterboard states that the Nazi flooding of the plain was an act of biological warfare – following Snowden’s conclusions – and another set of posterboard, which is credited to the scientific authority of tthe Istituto di Parassitologia of Rome University’s “La Sapienza”, claims instead that “the war” and “bombardments” raised the level of malaria incidences as the war progressed. Meanwhile, the diorama merely sides with my interviewees, showing the Nazis as evacuators but giving no hint as to why locals needed to move into the hills above the plain in the first place.

In sum, the perspective offered by the Piana delle Orme is not only politically non-committal; it reflects a persistently “bottom-up” view. The King left, and Jews were deported, but these scenes are staged to represent the lack of context that ordinary Italians had at the time. The events portrayed are full of fascist authorities and the war scenes hold Nazi military figures, but the Piana produces an inconclusive, even unclear, “history”. It depicts Italian citizens as without agency – indeed, it reproduces their non-agency at the time – doing the exact opposite of the work done by Germany’s state-overseen museums. As in so many other depictions, Italians here are victims or bystanders, and never perpetrators17.

The problem with this deliberately non-committal depiction – and the challenge for a future government-supported museum to do better – is that the lack of a clear central political narrative leaves room for an indirect reframing of Mussolini as only a source of good. For instance: the Piana’s narrative of the War begins with Mussolini’s declaration that Italy is now a participating power, but Mussolini’s responsibility at any stage is never mentioned again. I took Mr De Pasquale at his word that he wanted to create an apolitical immersive experience of his beloved Agro pontino area and its unusual history. Yet the effort to represent history this way simply reinforces the indecisiveness of so many Italian depictions, ultimately producing openness to “nostalgia” for fascism. In 2009, the restaurant at the Piana delle Orme sold wine bottles with Mussolini on the labels, even though nothing in the barracks’ displays was openly pro-fascist. A few years later, the bottles were gone from the restaurant, but the shop sold reproductions of the 1932 “Duce scarf”, which is covered in wheat stooks and the word “Duce” – a pro-Mussolini propaganda item. In 2018, these were gone also. One gets the sense that the Piana delle Orme is either continually having to check the encroachment of pro-Mussolini customers’ tastes, or having to re-evaluate where it places the limits of its own appreciation for the dictator.

Given that this was a personal collection rather than a state-sanctioned museum, we can hardly criticize Mr De Pasquale for depicting what life in Italy looked like from the bottom-up perspective he favored. In a country that foregoes its own authority by never creating a national story or museum, his effort and investment are admirable. Still, it gives us some direction as to what not to do in the kind of official museum Predappio proposes.

The Museum that Is: Predappio and Villa Carpena

Meanwhile, the unwitting irony of Predappio’s project is that it fails to acknowledge the multiple ways in which the town itself is already, for many, a museum. The Predappio of today was built in the mid-1920s as an explicit glorification of Mussolini’s origins, and immediately became, by design, a site of pilgrimage18. Today, visiting “nostalgici” (“nostalgics” for fascism) routinely tour the house where Mussolini was born, and the crypt where his remains sit in a sarcophagus surrounded by the remains of his extended family members, all surrounded by ex-votos and mementoes. They sign the visitors’ books, which fill up quickly. Some follow up with a meal at the Trattoria del Moro, where Mussolini first met the mother of his legitimate children, “donna” Rachele. They can choose wine in bottles bearing Mussolini on the label; the cloth napkins bear a prominent embroidered “M” (presumably for “Moro” but with the chance that it doubles as a sign for “Mussolini” also). The fascio littorio, the emblem of fascism, still adorns the top of the church façade pediment, overlooking the same piazza as the casa del fascio.

Fascio littorio on San Antonio church, Predappio.

Out of public view, but there nonetheless, is the Madonna del fascio – a fascist Virgin Mary – which is visible in reproductions, themselves used in processions in Predappio commemorating Mussolini and fascism19.

Madonna del fascio tile-work, Predappio.

In short, as historian Simon Levis Sullam notes, “Predappio can be thought of as a mnemotopos, as a place that gave rise to a founder, and as a site of pilgrimage to the founder’s tomb, in which a religious component endures…”20; all of which make it unsuited for a (neutral) museum of fascism in Italy.

All the discussions so far, however, have omitted the Villa Carpena, or self-styled “Casa dei Ricordi”, roughly 13 km from Predappio and an essential stop on the pilgrimage of any committed “nostalgico”. If Predappio is implicitly inadequate because of its history, the “Casa dei Ricordi” issues an explicit challenge to any effort at clear, balanced historical narration. For here, we find the cult of Mussolini maintained, and even updated, with genuine fervor. A new museum in Predappio will have concretely to oppose the fairytale version of Mussolini that lives here, where he was a good family man, the only woman in his life was “donna” Rachele, and he was, most counterintuitively, a pious Catholic who exchanged letters with Padre Pio.

The house was once lived in by Mussolini and Rachele, and all of their children spent some of their early years there, keeping it beyond the deaths of their parents (Rachele died in it in 1979). Their son Vittorio was known to show people around it casually, and by the time Romano, the last surviving child, died in 2006, it had already passed in 1998 into the hands of Domenico and Adele Morosini, former entrepreneurs who retired in order to devote themselves to their cause, “memory” as embodied in the museum they have made in the house. The garden, the sheds, and the house interior are stuffed with memorabilia and plaques, to which are added increasing layers of testimonials offered by visitors. The attic floor, which houses the “study center”, is home to the stacks of signed visitor-books from Mussolini’s crypt.

Overall, the presentation emphasizes Mussolini’s domesticity and Rachele’s “heroism” (having withstood the persecutions of the post-war State) through the tour of the kitchen, the dining room, Mussolini’s study, the children’s bedrooms, and ultimately, the master bedroom. While the building per se is auratic for “nostalgici”, having been inhabited by the duce, its objects and the way they are staged provide a dramatic blend of Catholicism with the cult of Mussolini. Statuettes of Padre Pio, and even a church pew, are intermingled with the countless items of Mussolini-worship, from busts to motorcycles, to his violin. At my most recent visit (in December 2017), our radiant guide exclaimed jubilantly, “I feel like I am in church here!” (mi sento in chiesa qui!).

In a noteworthy similarity to the Piana delle Orme, the Villa Carpena also showcases farming machinery such as tractors, a press, and a thresher, all contextualized with a reference to the “battle for wheat” waged by Mussolini. At one time, also like the Piana delle Orme, it featured an airplane21. The Piana collection and Villa Carpena are, when it comes to intent and orientation, utterly different. And yet they both dwell in the domain of public (rather than professional) histories of fascism, of the sort that are made possible by the lack of official ones. Villa Carpena favors alternate historiographies and its owners denigrate the mainstream as “against history”22. Ultimately, it illustrates even more clearly than the Piana delle Orme how an open-ended, “good Mussolini” without a lucidly contextualized narrative makes room for the cult of Mussolini to continue to thrive.

Predappio’s New Museum: Suggestions

From the available materials, Predappio’s museum project appears to have originated first from the desire to make some use of the casa del fascio, the largest building in Predappio, which has long been in disrepair and begs for a decision: it needs to be demolished, or restored. The project documentation begins with architectural materials and analysis (of roughly 200 pages) and discussions of conservation and restoration, and only ends with an outline of the museographical plan (at a mere 16 pages). In other words, the idea of creating a museum does not seem to have been the town’s priority. The museum plan itself is generic at best, with absolutely no reflection of, or on, its location, and no particular consideration of the specific museological opportunities afforded by the setting of Predappio. Instead, the displays as outlined follow the most conventional of historiographies, laying out step by step what any good textbook can already offer. There is no need to travel to Predappio to learn what the planned museum is designed to teach. It preaches to the choir of those who favor a chronological reconstruction of facts with various social and economic factors mixed in – matters that most likely will never attract the attention of the pilgrims to Predappio, in any case.

Furthermore, coverage of the project suggests that Predappio’s mayor, Frassineti, hopes that a museum will counteract the local cult activity. But it cannot do that per se; it needs specific engagement with relevant topics, facts, and political positions. The task of a new museum in Predappio must be first and foremost, not to ignore Villa Carpena, or Predappio’s own museum status at present, or indeed the forever-fascist aura of the building they intend to use, the casa del fascio; but to counter these, by proposing a different, anti-cultic narrative. Displays should document Mussolini’s origins, and his cult in terms of its origins too. The methods of those who built the cult up during the regime should be made explicit, and juxtaposed with the methods still in effect today (such as the dextrous use of Catholic imagery and overtones)23. They should also clarify what was false in the cultic representations of Mussolini then – and what is false now. Point by point, such a museum should confront the falsehoods that still cluster around the dictator, and demystify him as pugnaciously as possible. This would be a museal use of the building (or even for a new building replacing it) that is fitting for its place, Predappio, and the best possible use of the opportunity it provides. Engaging fully with what is at stake in the pilgrims’ visits would be a true innovation for the town of Predappio, and a new horizon in Italian representations of fascism and its leader.

Conclusion

Scholars of the Italian 20th century typically rely on the trope of “divided memory”24 to summarize the faultline that has cut through Italian society and politics since the still-unresolved civil war of 1943-1945. But in the context of historical representations and what is at stake in creating museums, I would characterize the problem, rather, as one of ambivalent memory: a scene that can be read “either way”, or an entire museum itinerary that plays to “all sides”, in the end making no claims for itself and teaching nothing new25. I propose that instead we see it as ambiguous, uncommitted memory — the risk being that concurrent historical memories, over time, develop into inverse universes. In one of these universes, conspiracy theories are taken for historical truth, and if no one argues against them directly, so they will remain.

I offer a last example of how commemorating all parties’ views non-committally results in a symbolic and cognitive no-exit: the site in Giulino di Mezzegra where Mussolini and Claretta Petacci died has signage from loyalists, on the one hand – around the gate of Villa Belmonte, a crucifix for Mussolini, and portraits of the two, framed together – and a few steps away, signage from the Partisans’ Association (Associazione Nazionale dei Partigiani d’Italia, or ANPI) dispassionately (but righteously) underscoring that Mussolini’s was an execution carried out on military orders. A third sign, with an explanatory paragraph, belongs to the Museum of the End of the War in Dongo described above. Here the idolatry-worthy and execution-worthy Mussolini co-exist (joined by the textbook version), unmediated and shedding only confusion as to the meaning and character of Italy’s fascist dictator, ad infinitum. If official museums are created, they should strive to break this impasse.

Notes

1

I am thankful for the grants and fellowships that have allowed me to visit the museums discussed here, from the American Council of Learned Societies, the École Française de Rome, the National Endowment for the Humanities, the University of California - Berkeley, and Université-Paris Est Créteil; and to the National Humanities Center, where the article was written. Many more people than I can list here have accompanied me to the Piana delle Orme, and some have discussed it with me many times since; a few have also joined me on visits to Villa Carpena’s ‘Casa dei Ricordi’. In particular I am delighted to thank Patricia Gaborik, Stephanie Malia Hom, Anne Marijnen, and Richard Wittman. I am further grateful to Patricia Gaborik for commenting on a draft of this article.

2

Michael Birnbaum and Stefano Pitrelli, “The Surprising Reason Mussolini’s Home Town Wants to Build a Fascism Museum”, 31 January 2018.

3

Passés futurs. Uncontrolled past [online] ;

Doppiozero. Museo del fascismo a Predappio: perché sì, perché no o perché forse? [online] ;

Doppiozero. Predappio sì perché? [online] ;

Doppiozero. Documentare il fascismo [online] ;

Doppiozero. Contro il Museo del fascismo [online] ;

E-Review. Rivista degli Istituti Storici dell’Emilia Romagna in Rete. Osservatorio Predappio. Per discutere del progetto di un museo sul fascismo [online] ;

Il Blog di Wu Ming. Predappio Toxic Waste Blues parts 1 , Predappio Toxic Waste Blues parts 2 , Predappio Toxic Waste Blues parts 3 [online].

Serge Noiret, “La public history italiana si fa strada : un museo a Predappio per narrare la storia del ventennio fascista”, Digital and Public History, 9 May 2016.

5

For a helpful overview of the discussions in sequence, see Micro Carrattieri, “Predappio sì, Predappio no… Il dibattito sulla ex Casa del fascio e dell’ospitalità di Predappio dal 2014 al 2017”, E-Review. Rivista degli Istituti Storici dell’Emilia Romagna in Rete, 25 April 2018.

6

This is not meant to dismiss the essential post-de-Felicean Italian scholarship delving deeply into the meaning(s) of Mussolini, such as: Luisa Passerini, Mussolini immaginario. Storia di una biografia 1915-1939, Laterza, 1991, and Sergio Luzzatto, Il corpo del duce, Turin, Einaudi, 1998.

7

In particular, see: Matteo Pasetti, “‘Modello Germania’? Sulle rappresentazioni museali del nazionalsocialismo”, E-Review. Rivista degli Istituti Storici dell’Emilia Romagna in Rete, 25 April 2018.

8

Propaganda of the 1930s (in Italian, German, English, and French) put the Pontine Marshes reclamation and settlement at the forefront of the regime’s self-proclaimed successes. Studies of the area by architectural historians, urban historians, and geographers are numerous; some essential sources are Riccardo Mariani, Fascismo e 'città nuove', Milan: Feltrinelli, 1976; Diane Ghirardo and Kurt Forster, “I modelli delle città di fondazione in epoca fascista”, in Cesare De Seta (ed.), Storia d'Italia, insediamenti e territorio, vol. 8, Turin, Einaudi, 1985, p. 628-674; Diane Ghirardo, Building New Communities. New Deal America and Fascist Italy, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1989, p. 46-82; Federico Caprotti, Mussolini's Cities. Internal Colonialism in Italy, 1930-1939, Youngstown, NY, Cambria Press, 2007; Helga Stave Tvinnereim, Agro Pontino. Urbanism and Regional Development in Lazio Under Benito Mussolini, Oslo, Solum Forlag, 2007; Antonio Pennacchi, Fascio e martello. Viaggio per le citta del duce, Bari and Rome, Laterza, 2008; and Daniela Spiegel, Die città nuove des Agro Pontino. Im Rahmen der Faschistischen Staatsarchitektur, Petersberg, Michael Imhof Verlag, 2010.

9

De Pasquale, personal communication, 24 June 2000.

10

“la strutturazione, i criteri espositivi e lo sviluppo rendendolo sempre più prestigioso e scientificamente qualificato” (Luigi Zaccheo, “Presentazione”, in Luigi Zaccheo, Museo Piana delle Orme, Ariccia, Associazione Museo Piana delle Orme, 2015, p. 7).

11

“un museo da autodidatti rinunciando al ruolo degli “esperti” che per De Pasquale tendevano a snaturare la sua idea di museo… Mariano voleva… un luogo che fosse vissuto e condiviso, e non un cimitero o un semplice contenitore di cose morte; un luogo dove l’elemento centrale e preminente non fosse la sua collezione, ma chi lo visitava. È stata questa l’impresa più difficile, rendere il museo “vivo”, evocativo, empatico, interattivo.” “… è stato… complicato far capire che il museo non era un tempio o un luogo di celebrazione, o ancora un luogo di élite o per esperti di settore”: Alda Dalzini, “Presentazione”, in Luigi Zaccheo, Museo Piana delle Orme, Ariccia, Associazione Museo Piana delle Orme, 2015, p. 3-4.

12

The collection’s points of pride include the tank that has appeared, among others, in the well-known films The English Patient and La vita è bella; a near-unique submersible tank; and an American fighter plane fished out of the sea, painstakingly restored, and reunited with the serviceman who had been shot down with it, brought for the occasion from the United States.

13

For a more thorough recounting and interpretation of the Piana delle Orme’s exhibits, see Suzanne Stewart-Steinberg, “Grounds for Reclamation: Fascism and Postfascism in the Pontine Marshes,” d i f f e r e n c e s: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies, 27(1), 2016 (doi: 10.1215/10407391-3522769)

14

Oscar Gaspari, "Il mito di Mussolini nei coloni veneti dell'Agro Pontino”, Sociologia, 12, n.s., 1983, p. 155-174.

15

As it has been known since Claudio Pavone, Una guerra civile. Saggio storico sulla moralità nella Resistenza, Turin, Bollati-Boringhieri, 1991.

16

See Frank Snowden, The Conquest of Malaria. Italy, 1900-1962, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2006. For a strongly opposed critique of Snowden’s conclusions, see: Erhard Geissler, Jeanne Guillemin, “German Flooding of the Pontine Marshes in World War II”, Politics and the Life Sciences, 29 (1), 2010, p. 2-23.

17

On Italian denials of accountability, see, for example: Michele Battini, Peccati di memoria. La mancata Norimberga italiana, Bari and Rome, Laterza, 2014; and Angelo Del Boca, Italiani brava gente?, Vicenza, Neri Pozza, 2005.

18

See Sofia Serenelli, “A Town for the Cult of the Duce: Predappio as a Site of Pilgramage”, in Stephen Gundle, Christopher Duggan, Giuliana Pieri (eds.), The Cult of the Duce. Mussolini and the Italians, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2013, p. 93-109.

Also note the website of ATRIUM (Architecture of Totalitarian Regimes of the XXth Century in Europe’s Urban Memory), calling Predappio an architectural “open-air museum”. Its principal architect-planner was Florestano di Fausto, a career employee of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and the most prolific of Italian architects in the colonies (Libya and Rhodes in particular); see Mia Fuller, Moderns Abroad. Architecture, Cities, and Italian Imperialism, London, Routledge, 2007, p. 128-132; and Sean Anderson, “The Light and the Line: Florestano di Fausto and the Politics of ‘Mediterraneità’”, California Italian Studies, 1, 2010.

19

See Maria Elena Versari, “È fascista la Madonna del fascio? Arte e architettura a Predappio tra conservazione e polemica politica”, in Luciano Curreri, Fabrizio Foni (eds.), Fascismo senza fascismo? Indovini e revenants nella cultura popolare italiana (1899-1919 e 1989-2009), Cuneo, Nerosubianco, 2011, p. 134-144.

20

“Predappio può essere pensato come mnemotopo, in quanto luogo che ha dato origine a un fondatore e in quanto méta di pellegrinaggio presso la tomba del fondatore, in cui persiste una componente religiosa…” (Simon Levis Sullam, “Contro il museo del fascismo,” Doppiozero, 31 March 2016, ).

21

The plane appears in the DVD, which provides a tour of the house and grounds: Casa dei Ricordi. Villa Mussolini, n.d. (but purchased in 2010).

22

Personal communications at the time of my visits in 2010 and 2017. The biography of Mussolini they favor is Nicholas Farrell, Mussolini. A New Life, London, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2003. Farrell spent time doing research for the book at the Villa Carpena, according to the owners; copies in Italian translation are sold there.

23

With specific reference, of course, to Emilio Gentile, Il culto del littorio. La sacralizzazione della politica nell’Italia fascista, Bari and Rome, Laterza, 1993, and the discussions that followed from its publication.

24

The expression has been canonical at least since Giovanni Contini, La memoria divisa, Rizzoli, 1997, which concerns one particular cluster of Nazi massacres in Tuscany in summer 1944. It now summarizes the vast array of conflicted political memories in 20th century Italy: see John Foot, Italy’s Divided Memory, Palgrave, 2009.

25

There are unfortunately-rare exceptions, such as the temporary exhibition Hercules e la guerra at Naples’ National Archaeological Museum (Museo archeologico nazionale) (29 September 2018 – 31 January 2019), which plainly points the finger at Mussolini for the antisemitic “racial laws” (leggi razziali) of 1938 rather than laying the blame on Hitler; and clearly notes the internment of civilians in concentration camps by the Italian government, prior to Germany’s deportations begun in late 1943.

Bibliographie

Sean Anderson, “The Light and the Line: Florestano di Fausto and the Politics of ‘Mediterraneità’”, California Italian Studies 1, 1 (2010).

Michele Battini, Peccati di memoria: la mancata Norimberga italiana, Bari and Rome, Laterza, 2014.

Michael Birnbaum and Stefano Pitrelli, “The Surprising Reason Mussolini’s Home Town Wants to Build a Fascism Museum”, 31 January 2018.

Federico Caprotti, Mussolini's Cities: Internal Colonialism in Italy, 1930-1939, Youngstown, NY, Cambria Press, 2007.

Micro Carrattieri, “Predappio sì, Predappio no… Il dibattito sulla ex Casa del fascio e dell’ospitalità di Predappio dal 2014 al 2017”, E-Review. Rivista degli Istituti Storici dell’Emilia Romagna in Rete, 25 April 2018.

Giovanni Contini, La memoria divisa, Milan, Rizzoli, 1997.

Angelo Del Boca, Italiani brava gente? Un mito duro a morire, Vicenza, Neri Pozza, 2005.

Nicholas Farrell, Mussolini: A New Life, London, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 2003.

John Foot, Italy’s Divided Memory, New York, NY, Palgrave, 2009.

Mia Fuller, Moderns Abroad: Architecture, Cities, and Italian Imperialism, London, Routledge, 2007.

Oscar Gaspari, "Il mito di Mussolini nei coloni veneti dell'Agro Pontino", Sociologia 12, n.s. (1983): 155‑174.

Erhard Geissler and Jeanne Guillemin, “German Flooding of the Pontine Marshes in World War II”, Politics and the Life Sciences 29 (1)(2010): 2‑23.

Emilio Gentile, Il culto del littorio. La sacralizzazione della politica nell’Italia fascista, Bari and Rome, Laterza, 1993.

Diane Ghirardo and Kurt Forster, "I modelli delle città di fondazione in epoca fascista", in Cesare De Seta, ed., Storia d'Italia, insediamenti e territorio, volume 8, Turin, Einaudi, 1985, pp. 628‑674.

Diane Ghirardo, Building New Communities: New Deal America and Fascist Italy, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1989.

Simon Levis Sullam, “Contro il museo del fascismo”, Doppiozero, 31 March 2016.

Sergio Luzzatto, Il corpo del duce, Turin, Einaudi, 1998.

Riccardo Mariani, Fascismo e 'città nuove', Milan, Feltrinelli, 1976.

Matteo Pasetti, “ ‘Modello Germania’? Sulle rappresentazioni museali del nazionalsocialismo,” E-Review. Rivista degli Istituti Storici dell’Emilia Romagna in Rete, 25 April 2018.

Luisa Passerini, Mussolini immaginario. Storia di una biografia 1915-1939, Bari and Rome, Laterza, 1991.

Claudio Pavone, Una guerra civile. Saggio storico sulla moralità nella Resistenza, Turin, Bollati-Boringhieri, 1991.

Antonio Pennacchi, Fascio e martello. Viaggio per le citta del duce, Bari and Rome, Laterza, 2008.

Sofia Serenelli, “A Town for the Cult of the Duce: Predappio as a Site of Pilgramage”, in The Cult of the Duce: Mussolini and the Italians, edited by Stephen Gundle, Christopher Duggan, and Giuliana Pieri, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2013, pp. 93‑109.

Frank Snowden, The Conquest of Malaria: Italy, 1900‑1962, New Haven, Yale University Press, 2006.

Daniela Spiegel, Die città nuove des Agro Pontino: Im Rahmen der Faschistischen Staatsarchitektur, Petersberg, Michael Imhof Verlag, 2010

Suzanne Stewart-Steinberg, “Grounds for Reclamation: Fascism and Postfascism in the Pontine Marshes,” d i f f e r e n c e s: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 27(1)(2016), doi 10.1215/10407391-3522769.

Helga Stave Tvinnereim, Agro Pontino: Urbanism and Regional Development in Lazio Under Benito Mussolini, Oslo, Solum Forlag, 2007.

Maria Elena Versari, “È fascista la Madonna del fascio? Arte e architettura a Predappio tra conservazione e polemica politica”, in Fascismo senza fascismo? Indovini e revenants nella cultura popolare italiana (1899‑1919 e 1989-2009), edited by Luciano Curreri and Fabrizio Foni, Cuneo, Nerosubianco, 2011, pp. 134‑144.

Luigi Zaccheo, Museo Piana delle Orme, Ariccia, Associazione Museo Piana delle Orme, 2015.