All three “monotheistic” religious traditions set out a conception of time as irreversible, thereby differing from the cyclical models found in other thought-systems1. The world was created by God at a specific “moment”. Throughout its course it is dependent upon this divine creator, who alone is in a stable, unchanging, and eternal fashion. The created universe, for its part, is destined to disappear. Within the field of eschatology, and more precisely the predicted end of history for human societies, the three scriptural traditions display certain convergences, all referring to final wars in which forces supporting God confront those of his Negation; they also refer to the appearance of a saviour and leader sent by God – the Messiah or Mahdî – who will bring order and harmony, both amongst men and between humanity and God. Yet there are also major differences in the way the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim traditions think about the end of time. We first need to go briefly over these conceptions, before looking more specifically at Sunni eschatology.

Saint John the Baptist's grave, Umayyad mosque of Damascus, Syria.

Jewish, Christian, and Muslim eschatology

Judaism, unlike the Judean national religion prior to exile, only really became aware of its existence when faced by the terrible threats posed by the Assyrian conquests and the disappearance of the kingdom of Israel (722 BC, with the taking of Samaria), followed by the Babylonian military campaigns which resulted in the destruction of Jerusalem and the Temple of Solomon (587 BC)2. The period of exile in Babylon, which came to an end in 538 with the Edict of Cyrus, was also a time when Judaic eschatological thought matured, as made apparent in several prophetic books. Eschatological enquiry has continued throughout the history of the Jewish people, and right up to the present day.

Old city of Jerusalem with Salomon’s Temple.

These events were all interpreted from a theological perspective endowing them with meaning. Faced with external threat, prophets had emphasised that divine punishment was imminent; and faced with fields of ruins, other texts announced that reconstruction would follow from the Lord’s forgiveness. Jewish messianism first appeared with the prophet Isaiah3. He announced the advent of a leader, a king missioned and anointed by God, who would restore the kingdom of David, and establish lasting universal peace, for the States and empires of the world would bear him allegiance. He initially drew on a disparate set of predictions taken from various sources, not on any unified body of doctrine. Gershom Scholem, in his study of Jewish eschatological doctrines over time, distinguishes between two types of messianism that combine in variable ways4. The first type is national messianism, largely political in nature. This does not rely on any secret knowledge and is addressed to all, with the predictions of the prophets relating primarily to restoring the kingdom of David. The second type may be traced as far back as the book of Daniel, and was developed by several great authors of the Kabbalah such as Abraham Abulafia (thirteenth century). It is more utopian and spiritual in nature, and linked to belief in two dimensions of the world, that of the present world (‘olam ha-zé), and that of the world to come (‘olam ha-ba). For this apocalyptic messianism, the restoration is no longer to be understood from a purely historical perspective, since it ushers in another dimension of history with the advent of another world, that of ‘olam ha-ba, which will transpire after a series of cataclysms. But both types of messianism are a “theory of catastrophe”5.

Judaism has given rise to a series of messianic declarations, taking the form of armed revolts and pacific preaching, though these are too numerous to be listed here. The most famous are those of Jesus, then the insurrection of 66 AD, followed by the destruction of the Temple in 70 AD; and the Bar Kokhba revolt (133-135 AD), which resulted in the Jews being exiled from Jerusalem6. The messianic preaching of Sabbataï Tsvi (d. 1676), who eventually apostatised, as well as that of his subsequent disciples, left their mark on history7. The list is long, and could be extended up to the present day with the messianic teachings of the Hasidic Lubavitch current8.

Destruction of the Jewish Temple, Francesco Hayez (1791-1882).

Destruction of Jerusalem, Heinrich Merz (1806-1875).

It should pointed out that messianism is not however a central belief in the Bible, or in Judaism in general9. It is possible to be a very orthodox Jew without attaching much importance to it. And those who write about messianism put forward very diverse interpretations. It should nevertheless be observed that messianic themes have a widespread and robust presence in contemporary Judaism, and influence various milieus among the Israeli population10.

Panorama of Jerusalem, beginning of 20th century.

Christianity, for its part, traces its roots back to messianic preaching in two ways. It is messianic in origin, since Jesus came to preach the advent of the Kingdom announced by the prophets of Israel, where this was to be brought to pass by adhering to his mission and even more so by placing faith in his person. The Kingdom preached by Jesus was not political in nature, lying clearly on a horizon of spiritual fulfilment. But this horizon took on a universal dimension after he was put to death and the announcements of his resurrection, with his disciples declaring he was alive and predicting his return, his parousia. It is said that when this occurs the spiritual dimension of the Kingdom will be fulfilled definitively, transpiring in a new Earth11. Hence Christian societies throughout history have awaited the second messianic coming. The prediction of “one thousand years of peace” on earth mentioned in the book of Revelation (20:6-10) went on to mark popular Christian eschatology by inspiring millenarian upswells that were sometimes political in nature, a phenomenon that occurred as of the early centuries of Church history. St Augustine criticised these outbursts vehemently, stating most clearly that the City of God, though admixed with the terrestrial city here on earth, was nevertheless wholly distinct, belonging to a higher order of being. But millenarian tendencies have occurred throughout subsequent history. Some of the most famous of these currents are those that draw their inspiration from the work of Joachim of Flore, and the revolts that started to arise as of the Reformation, often transpiring in challenges against the established order12.

Jesus preaching on the shore of the Sea of Galilee, Adriaen van Stalbemt (1580-1662).

The Second Coming, Georgios Klontzas, end of 16th century.

The detail at the right bottom represents the punishment of the weak, led to hell.

The presence of millenarian themes in contemporary Christian thought, especially in the United States, is a well-known fact. This is not the preserve of certain extreme fanatic sects, for these themes having been thoroughly absorbed by the evangelical social fabric, which views the return of the Jews to the Holy Land and the creation of the State of Israel as fulfilling the predictions of the biblical prophets. Such a vision of history inevitably has a significant political impact.

A nation under God's command, Mac Naughton.

Stained glasses, Chartres Cathedral, Second Coming of Jesus.

Source : http://counterlightsrantsandblather1.blogspot.fr/2014/08/chartres.html

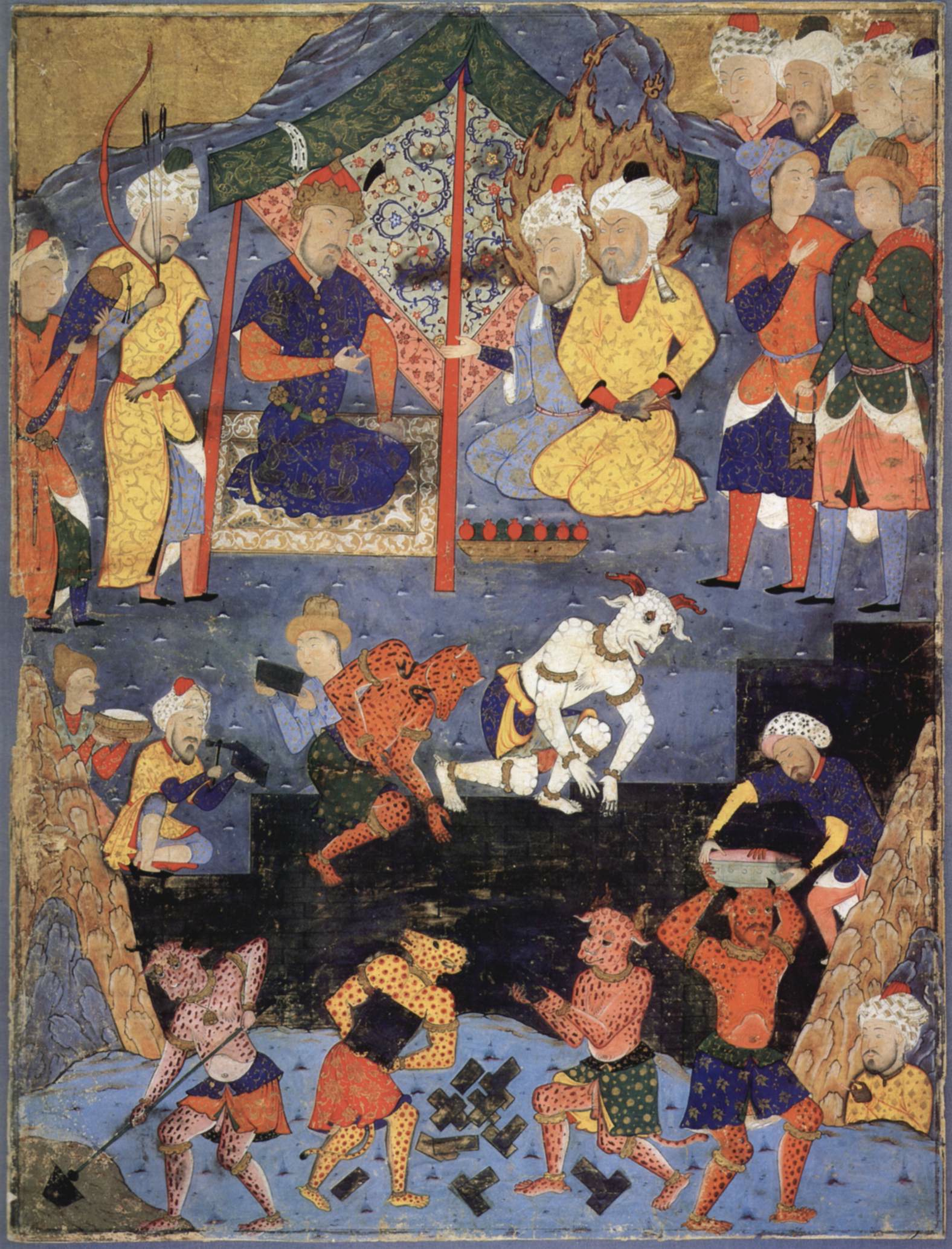

Let us now turn to eschatology in Muslim lands. The early Qur’anic message is apocalyptic, and may be resumed as: convert, for the end is nigh. It will come suddenly, in a flash. The Arabs of Mecca to whom this message was addressed were invited to repent and place their faith in the unique God, Allah, under threat of terrible punishment, in the form of an unforeseeable, irresistible, and (supra-)natural catastrophe. The ancient suras of the Qur’an do not make any distinction between the wars marking the end of history and other final cataclysms preceding the Resurrection proper, differing in this respect from the Jewish and Christian traditions. Men will be talking when the Cry will ring out – it will be death then Resurrection with no gap between the two (36: 48-52). Other less clear narrative elements were subsequently added, such as the eschatological role of Jesus (43: 61; 4: 159), and the destructive invasion of the peoples of Gog and Magog (18: 98-101). But overall, the two “moments” seem to be grouped together in ancient Qur’anic discourse, with the material collapse of perverse cities and the resorption of creation occurring in a single destructive wave, making way for the establishment of a new creation.

Alexander the Great oversees the building of the wall, attributed to 'Abd al-'Aziz. Miniature of the Books of Divinations (Falnama) [of Ja’far al-Sadiq] for Tahmasp I (r. 1524-76), between 1550 and 1560.

But Islamic eschatological doctrines went further than this. The consequences of various conflicts arising immediately after the death of Muhammad in 632 – without any planned succession or the Qur’an even written – fed into Muslim ideas about the apocalypse. At the time, certain of his Companions did not believe in the reality of his death. There are many indications the first Muslims foresaw the End as very close at hand. The hadiths, or oral teachings attributed to the Prophet Muhammad, contain archaic elements showing he expected the End of History and the world to be imminent: “the time of my advent and the Hour are like these two”, he said, holding his index and middle finger together13. Another hadith refers to his expectation that before dying he would meet Jesus and be able to greet him (and should he be unable to do so, at least those of his Companions who survived him would). The Hour was to arrive one brief generation after his death14. Still other hadiths show Muhammad prepared to identify the Antichrist as being Ibn Sayyâd, a young Jew from Medina with mediumistic abilities15. Further examples could be provided. The thesis put forward by Paul Casanova about the scale of eschatological expectation in early Islam has been confirmed and amended by more recent scholarship16.

Most of the eschatological material about wars and catastrophes at the end of time may in fact be found in collections of hadiths, often in chapters titled “Book of seditions, Kitâb al-fitan”, in which the term fitna, plural fitan (sedition or revolt) points to an important reference in the Qur’an17. These hadiths were gathered and set down in writing well after Muhammad’s death, a century and a half later in the case of the main collections. It is not possible to come to a firm conclusion about the authenticity of the words attributed to him. Ibn Khaldoun has expressed numerous doubts as to their reliability, supposing them to have been put into circulation for the benefit of various political currents during the troubled periods following the Prophet’s death18. It is nevertheless true that Sunni Muslims place great faith in them – which is what matters here – for they hold Muhammad to have been inspired at each instant, and his words to be infallible since God guarantees them against all error.

Sunni eschatology and the signs marking the end of time

Prior to the consolidation of Sunnism during the eighth and ninth centuries, Shiism was no doubt more active in taking up original Islam’s imminent expectation of cosmic overthrow, and Shiite currents over time have conceptualised a form of “permanent apocalypse”19. For them, Muhammad named his successors, who are the legitimate Imams of the community, but have been rejected by the Sunni majority. A final Imam, al-Mahdî, “occulted” in 940, will come at the End of time to repel oppressors (Sunnis) and fill the world with justice – that is to say, ensure the victory of the Shiite party. Very many Shiite revolts have occurred over the centuries, several of which met with success. But they all eventually ran out of steam, for their eschatological promises failed to materialise. Such was the fate of the Carmatian State and the Fatimid dynasty in the tenth and eleventh century, and then of the Safavid dynasty in Iran (16th to 18th century).

Poster of Imam Ali, Iran.

That being said, Sunnism at all periods has also produced a sizeable body of apocalyptic preaching. The idea that the end of time was very near admittedly diminished over the generations. Several hadiths indicated that the fall of the Byzantine capital would be one of the main signs of the “Hour”, and hence of the end of history20. The Omayyad caliphs (660-750) waged several vigorous land and sea offensives against Constantinople, though these resulted in failure. Hence the eschatological horizon of the Islamic community expanded, and overly precise predictions about fulfilling the final military campaign petered out. Still, the idea waxed and waned amongst the Sunni community over the course of the centuries. Visions of the advent of the Hour were siphoned into attempts to legitimise political movements, such as that of the Almohads in the Maghreb (twelfth and thirteenth century); this continued up until the modern period in the struggle against colonisation, as was the case with the revolt led by Mahdi Muhammad Ahmad (d. 1885) in Sudan, to give but one example.

Sunni scholars attach a certain importance to traditions relating to “the portents of the Hour”, though without treating them as an axiom of dogmatic faith. Ibn Khaldun alludes to them, mocking the credulity of the masses who adhere to such preachings which strike him as transparently false21. What elements of the literature about the “portents of the Hour” transpire in the collections of hadiths? This corpus is read widely, and extensively circulated today, not only amongst Islamist networks. I shall resume a few points, selecting those which currently seem to be the most significant, and in particular those referred to recently on social media networks.

Translation in English of The Muqaddinah. An Introduction to History of Ibn Khaldun, by Franz Rosenthal.

A regressive, “descending” notion of the history of the Muslim community developed, according to which men are ever more sinful and unbelieving over the course of time. Their sins will contrast with the supposed admirable virtues of early-generation Muslims. According to these texts, the end of time will be made manifest by struggles between Muslims22. The Arab element in Islam will be wholly weakened, as attested in 750 by the advent of the Abbasid dynasty, which saw the social and political ascension of many Iranians and Turks.

Battle between the first Umayyad caliph Muawiya and the caliph Ali in 657, Siffin's battle, Persian Safavid illustration, 1516.

Source : https://histoireislamique.wordpress.com/2014/04/24/regne-de-mouawiya-lomeyyade-41661-60680-tire-dal-fakhri-de-ibn-al-tiqtaqa-1302-lui-meme-tire-dibn-al-athir/

Society will experience a spectacular increase in wealth, while undergoing profound moral disarray23. Muslims will consume animal fat and large quantities of alcohol. This also occurred during the Omayyad and Abbasid empires as a result of conquests and rich booty, but once again the description applies to many periods, including the current one.

Religious science will be enormously weakened, with this sometimes being attributed to the large numbers of women in the final phases of history. The role of women will continue to increase, becoming far more numerous than men, and their husbands will obey them whilst neglecting their duties towards their own parents. On the whole there will be a return to idolatry and all this implies24. Sexual debauchery will spread openly, spilling out onto the streets, and men will become like animals25. Homosexuality will become commonplace. All of this will correlate to a weakening of faith and sincerity. There will be ever more apostasies and conversions with every passing day26.

In addition to these general characteristics of the end of time, certain more specific signs recur in the writings. The conquest of Constantinople, as just seen, is often presented as a major “portent of the Hour”. There will be a great final combat against Byzantines (al-Rûm, the Romans)27. The taking of Constantinople will be “the mother of great battles” (umm al-malâhim). Sometimes Rome stands in for Constantinople, leading to a certain degree of confusion in more contemporary literature28. The Rûm/Byzantines are, in an easy transposition, often currently identified as Westerners.

The first Arab siege of Constantinople.

Source : http://www.medievalists.net/tag/seventh-century/

Another event that is frequently mentioned in the hadiths is the appearance of the Antichrist, al-Masîh al-dajjâl, literally “the misleading Messiah”, a sort of charismatic anti-prophet guiding men towards false prosperity and away from religion. According to these hadiths, the Dajjâl will have one eye. He will cure the sick and, like Jesus, accomplish prodigious feats, proclaiming “I am your lord, anâ rabbu-kum”. He will win over much of humanity, including many of the faithful, due in particular to the spectacular nature of the miracles he will accomplish, and by the material abundance he will bring about29. An immense combat will follow, between impious forces and the small remaining number of believers. The hadiths give many varied and contradictory indications about the origin and circumstances of this combat.

But the texts nevertheless agree that the central zone of Islam will shift towards Syria (Bilâd al-Shâm). In principle the Centre of the Community lies in Hedjaz, the region of the sacred city of Mecca, where the Mahdî will appear30. Equally Medina, where Muhammad founded his community, will, like Mecca, be preserved by angels who will prevent the Dajjâl entering there31. According to other hadiths, it will nevertheless be destroyed and abandoned to wild beasts. Other words attributed to Muhammad describe it as a bed of discord where the Antichrist’s call will ring out. It will be destroyed by “the Ethiopian”, a wholly enigmatic figure32. These fairly contradictory indications seem to suggest that the region regarded as most holy by the Muslim community will be subverted at the end of time, and even perverted by heathenism.

But the “Shâm”, that is to say Syria in the mediaeval meaning of the term – “from the Euphrates to Ashqelon” – will be a key region for the fate of the community. It is the true centre, the head of a bird with the Maghreb and the Mashriq as its two wings33. “Go and take refuge in Shâm”, one hadith advises. Once all the earth has been devastated, Shâm will still be large enough to shelter those who have taken refuge there. It will expand to become the uterus for a child. The land of Shâm is blessed by God and by the Angels34. The people of Shâm, according to the hadiths, are the most trustworthy, the best believers, most especially at the end of time. When they disappear there will no longer be any faith. Even more importantly, the “apotropean saints”, or Abdâl35, will be present amongst them. In mystical Muslim thought, this sinful world of transgression is saved from destruction by the presence of an invisible hierarchy of saints whose purity and virtue stave off divine wrath, and a local tradition holds that forty of these “apotropean saints” reside in Damascus, thereby protecting the town until the end of time36.

Possible map of Damascus, 15th century.

Lastly, two figures will appear at the end of time to rescue the small remnant of Muslims, banding them together and guiding them towards final victory. The first is called Mahdî, meaning “the well guided”. He will be a descendant of Muhammad, and bear his name. He will be a just ruler and after vanquishing paganism will bring prosperity to humanity37. He needs to be distinguished him from Muhammad ibn Hasan al-Mahdî, the twelfth Imam of the Shiites, also viewed by them as being invested with an eschatological mission.

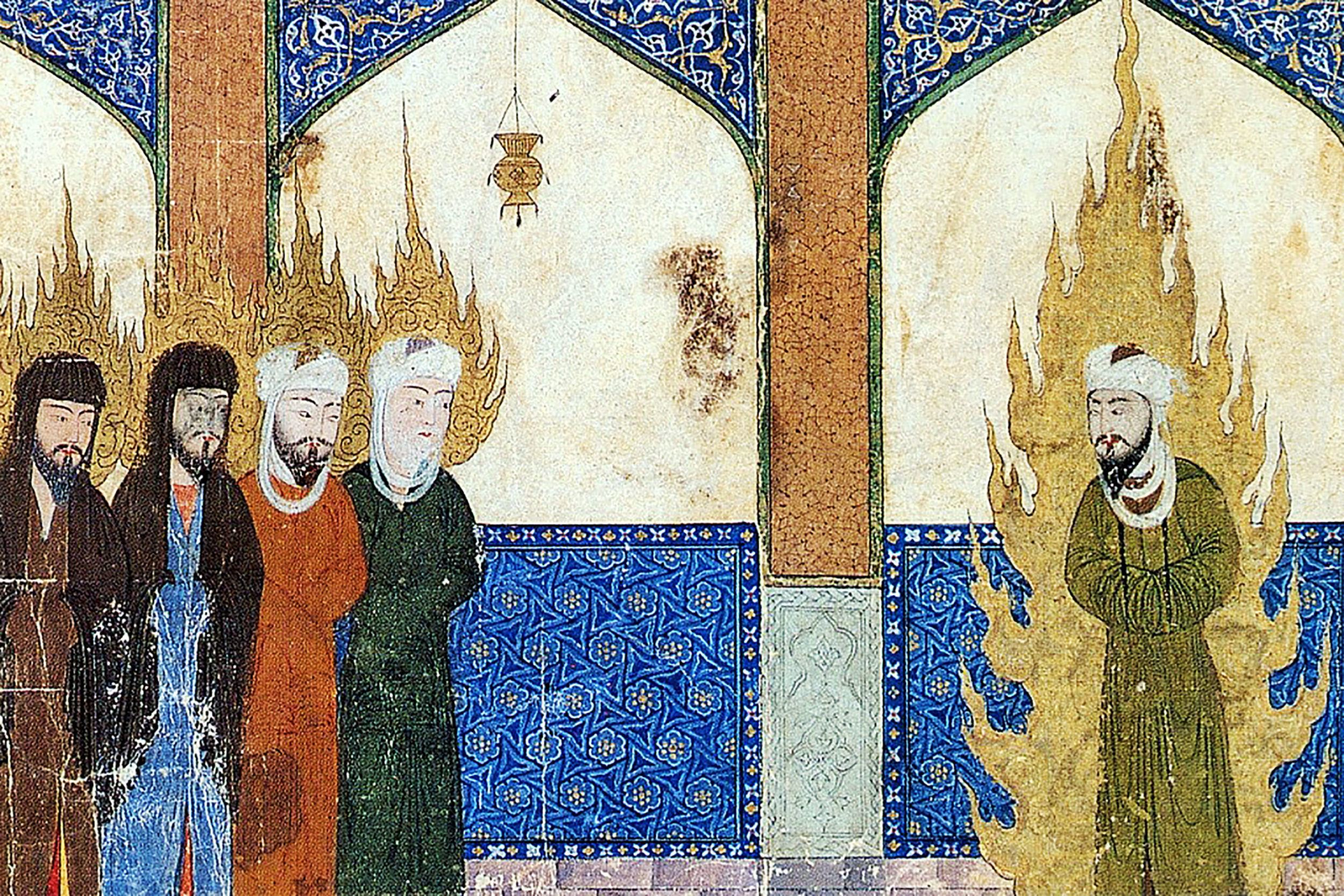

The second figure is Jesus. His eschatological role, as mentioned above, is referred to in the Qur’an in ambiguous terms (43: 61). The hadiths have more to say about this. Jesus, who according to the Qur’an was not crucified and has ascended to heaven, will descend to earth and go to Damascus to rally Muslims together38. He “will kill the swine and break the cross”. Then he will combat Gog and Magog, and kill the Dajjâl with his own hands using a spear. The Hour will rise over the faithful who have remained to fight alongside Jesus39 . Jesus will work together with the Mahdî, and – admittedly according to a different hadith – the two figures are in fact one of the same40.

Muhammed leads Abraham, Moses and Jesus in prayer, medieval Persian manuscrit.

Source: The Middle Ages. An Illustrated History, Oxford University Press, 1998.

The ultimate phase of the great final battle, malhama, will take place in Shâm, and more specifically in Palestine41. The sites of certain battles are even indicated: Dabiq, in Northern Syria, which at the time of writing in 2016 has been much in the news, ‘Aqabat Afîq, Lod, Lake Tiberius, and Jerusalem. The troops will be comprised of the elect, the “foreigners”, or ghurabâ’, mentioned in a famous hadith. One predictive hadith known as “the hadith of the spy, al-Jassâsa”, appears to indicate that this is where the Antichrist will strike42 . Damascus will become the new “Medina” where the faithful will come together, in order to deliver the new Mecca, namely Jerusalem. At the end, Jerusalem will become the central town of the new Muslim empire, and its new pre-eminence will be concomitant to the destruction of Medina. It is where Mahdî and/or Jesus will establish their sultanate. The setting up of this new holy geography is the subject of the hadith affirming that on the Day of Resurrection, Mecca will be transported to Jerusalem as a bride43.

Jesus will reign over humanity reunited under the banner of Islam. He will be just, and usher in an era of peace. His reign will mark the fulfilment of the sharia, and all non-Muslims in the world will be obliged to convert. It will be a moment of paradise, and wild beasts and domestic animals will live alongside one another44. Jesus will marry, have children, and die. He will be buried next to Muhammad and his two Companions Abû Bakr and ‘Umar45. But the length of his reign and his relationship to the Mahdî are not clearly spelt out.

Finally, let us point out that these events do not have the same meaning in Christianity. There is no mention of one thousand years of peace following on from a terrible and limited period of combat. Once the wars come to an end the reign of the Muslim Jesus will, according to the hadiths quoted here, be very brief. The final cataclysm will occur and the world be destroyed. The final Resurrection of all the dead will take place. The judgement of human deeds will occur in Jerusalem46.

Dome of the Rock, Jerusalem.

What may we conclude from these observations? The eschatology of Sunni Islam is not lifted directly from the Jewish and Christian traditions, despite echoes, similarities, and clear textual borrowings47. It contains clear traces of specific historical events, and of the political and military issues from the time when the Muslim community originated, a period covering more or less the first century and a half of the Hegiran era.

In fact, in the Muslim way of apprehending history, this heterogeneity takes on meaning once it is appreciated that these eschatological moments actually started during the Prophet’s lifetime. At each period of history Muslims, waging a combat that they view as ultimate, see themselves as directly continuing the campaigns of Muhammad. They do not perceive any temporal hiatus between the days of the Prophet and the end of time. The entire history of the Islamic community thus takes place within the series of “Portents of the Hour” prefiguring the Great Resurrection. There may have been several Dajjâl-s, several Mahdî-s, for ultimately they assume a constant function, recurrently giving meaning to specific historical situations. The eschatological period in the sense of a final moment will be a repetition, a conclusion, a signature fulfilling once and for all the meaning of the human adventure, as proclaimed fourteen centuries ago.

Notes

1

For examples see Mircea Eliade, Le Mythe de l’éternel retour. Archétypes et répétitions, Paris, Gallimard, 1969.

2

Thomas Röhmer, “Origines des messianismes juif et chrétien”, in J.-Ch. Attias, P. Gisel, L. Kaennel (eds.), Messianismes. Variations sur une figure juive, Geneva, Labor et Fides, 2000, p. 18-28.

3

Distinguishing the first Isaiah, who wrote in the eighth century BC, from the second (towards the end of the exile), and the third, who lived during the fifth century BC. Mentions of the Messiah may also be found in Jeremiah (chapters 22-23), who lived through the destruction of 587, in Ezekiel, one of the main prophets of the exile, and in Zachariah (writing post-exile, chapter 12:3-13).

4

Gershom Scholem, “Pour comprendre le messianisme juif” [1959], in G. Scholem, Le Messianisme juif. Essais sur la spiritualité du judaïsme, Paris, Calmann-Lévy, 1974, p. 23-69.

5

Gershom Scholem, “Pour comprendre le messianisme juif” [1959], in G. Scholem, Le Messianisme juif. Essais sur la spiritualité du judaïsme, Paris, Calmann-Lévy, 1974, p. 31; quoted by Michael Löwy, “Le messianisme hétérodoxe dans l’œuvre de Gershom Scholem”, in J.-Ch. Attias, P. Gisel, L. Kaennel (eds.), Messianismes. Variations sur une figure juive, Geneva, Labor et Fides, 2000, p. 144.

6

Bar Kokhba was initially recognised as the Messiah by Rabbi Akiba, who along with other rabbis subsequently desisted.

7

He claimed to be the Messiah in 1648, playing on expectations about the year 1666, before finally converting to Islam in that very year. Since then the Jewish world has displayed great distrust of messianic claims. See Gershom Scholem, Sabbataï Tsevi. Le messie mystique, 1626-1676, Paris, Verdier, 2008. There were many disciples and emulators of Sabbataï Tsvi, the most famous of whom was Jacob Frank (d. 1791) in Eastern Europe.

8

Menachem Mendel Schneersohn (d. 1994), the seventh and last representative of this line of rabbis, was profoundly venerated by his disciples. Many of them saw him as the Messiah, even after his death.

9

Peter Schäfer, Mark Cohen (eds.), Toward the Millenium. Messianic Expectations from the Bible to Waco, Leiden, Brill, 1998.

10

See Laurence Podselver, “Les jours du Messie”, in E. Aubin-Boltanski, C. Gauthier (eds.), Penser la fin du monde, Paris, CNRS Éditions, 2014, p. 391-423.

11

See Matthew 24; 2 Peter 3; The book of Revelation.

12

Joachim de Flore lived in southern Italy at the end of the twelfth century. Drawing on meditations in the book of Revelation and the book of Daniel, he predicted the advent of an "age of the Spirit", following on from that of Father (the period of the Ancient Alliance), and that of the Son (corresponding to the era of the Christian Church). This age of the Spirit was to commence in 1260, and be marked by the disappearance of the ecclesiastical hierarchy. Later, in the sixteenth century, Reformation preaching was heavily marked by an eschatological turn of mind. The German Peasants' War, accompanied by the apocalyptic predictions and preaching of Thomas Müntzer (d.1525), acquired such scale that Luther forcibly condemned it.

13

“Bu‘ithtu anâ wa-al-sâ‘a ka-hâtayn”. Bukhârî, al-Jâmi‘ al-sahîh, Cairo, Dâr al-sha‘b, 1987, no. 4936, 5301, 6503-6505. This hadith has been commonly interpreted over the course of the centuries as designating the eschatological significance of Muhammad's mission, as the last Prophet in human history according to Muslims.

14

Muslim, Sahîh, Cairo, Matbû‘at Muhammad ‘Alî Subayh, 1940, no. 7598-7601. Ibn Hanbal, Musnad, Cairo, Mu’assasat Qurtuba, undated, no. 7957, 7958, 7965; Michel Hayek, Le Christ de l’Islam, Paris, Seuil, 1959, p. 247. Pierre Lory, Min ta’rîkh al-hirmisiyya fî al-islâm, Jbeil, Byblion, 2005, p. 205-206.

15

Bukhârî, al-Jâmi‘ al-sahîh, Cairo, Dâr al-sha‘b, 1987, no. 1354-1356, 2638, 3032, 3055-56, 6173-74.

16

Paul Casanova, Mohammad et la fin du monde, Paris, 1913; David Cook, Studies in Muslim Apocalyptic, Princeton, Darwin Press, 2003.

17

Qur’an 2: 191: “Revolt is worse than slaughter” (“wa-al-fitna ashaddu min al-qatli”).

18

Ibn Khaldoun, Discours sur l’Histoire universelle. Al-Muqaddima (trans. V. Monteil), Paris, Sindbad, 1967-1968, vol. II, p. 632-678.

19

Mohammad Ali Amir-Moezzi, “Fin du temps et retour à l’origine”, in La Religion discrète. Croyances et pratiques spirituelles dans l'Islam shiite, Paris, Vrin, 2006, p. 297-315. And Mohammad Ali Amir-Moezzi, “‘Alî et le Coran”, Revue des sciences philosophiques et théologiques, vol. 98, 2014, p. 669-704.

20

Ibn Hanbal, Musnad, Cairo, Mu’assasat Qurtuba, undated, no. 22076, 22098, 22174.

21

Ibn Khaldoun, Discours sur l’Histoire universelle. Al-Muqaddima (trad. V. Monteil), Paris, Sindbad, 1967-1968, vol. II, p. 672-678.

22

Bukhârî, al-Jâmi‘ al-sahîh, Cairo, Dâr al-sha‘b, 1987, no. 85, 1036, 6037, 7061-65, 7121. It is worth noting that this prediction came to pass back in 656, with the civil war that broke out between the supporters and adversaries of the fourth caliph, ‘Alî.

23

Bukhârî, al-Jâmi‘ al-sahîh, Cairo, Dâr al-sha‘b, 1987, no. 80, 5231, 5577, 6808; Tirmidhî, Sunan, Beirut, Dâr ihyâ al-turâth al-‘arabî, undated, no. 2210-12, 2221, 2302-2222; al-Hâkim al-Naysâbûrî, Al-Mustadrak ‘alâ al-sahîhayn, Beirut, Dâr al-kutub al-‘ilmiyya, 1990, no. 8516; ‘Abd al-Bâqî Mansûr, Mawsû‘at ‘alâmât al-sâ‘a, Aleppo, Dâr al-Rifâ‘î and Dâr al-qalam al-‘arabî, 2005, p. 25, 31. Most of the hadiths about society's moral decadence are also to be found in Muhammad al-Barzanjî, Al-ishâ‘a fî ashrât al-sâ‘a, Beirut, al-Maktaba al-‘asriyya, 2005, p. 83-101.

24

Muslim, Sahîh, Cairo, Matbû‘at Muhammad ‘Alî Subayh, 1940, no. 7483, which also refers to a return to pre-Islamic pagan religion.

25

On people openly copulating, see the sahîh hadith, quoted by Suyûtî in Nuzûl ‘Îsâ ibn Maryam (translated into French under the title Jésus, l’antéchrist et la fin du monde, Lyon, Alburda, 2000, p. 124). See too Muslim, Sahîh, Cairo, Matbû‘at Muhammad ‘Alî Subayh, 1940, no. 7560, on the idea of believers being "recalled", leaving only the wicked on earth, who will be caught unawares by the final sudden catastrophe.

26

Ibn Hanbal, Musnad, Cairo, Mu’assasat Qurtuba, undated, no. 6168, 8017, 8835, 9061, 9063, 10782, 15791, 18462, 19677, 19745.

27

Bukhârî, al-Jâmi‘ al-sahîh, Cairo, Dâr al-sha‘b, 1987, no. 2924; Muslim, Sahîh, Cairo, Matbû‘at Muhammad ‘Alî Subayh, 1940, no. 7463, 7466; 4296, 4297.

28

Ibn Hanbal, Musnad, Cairo, Mu’assasat Qurtuba, undated, no. 6645; ‘Abd al-Bâqî Mansûr, Mawsû‘at ‘alâmât al-sâ‘a, Aleppo, Dâr al-Rifâ‘î and Dâr al-qalam al-‘arabî, 2005, p. 176-178.

29

Bukhârî, al-Jâmi‘ al-sahîh, Cairo, Dâr al-sha‘b, 1987, no. 86, 1555, 1879, 1881, 3439, 3450, 4402, 7122-7133. Numerous hadiths about his description may also be found in Muslim, See too ‘Abd al-Bâqî Mansûr, Mawsû‘at ‘alâmât al-sâ‘a, Aleppo, Dâr al-Rifâ‘î and Dâr al-qalam al-‘arabî, 2005, p. 203 et seq.

30

‘Abd al-Bâqî Mansûr, Mawsû‘at ‘alâmât al-sâ‘a, Aleppo, Dâr al-Rifâ‘î and Dâr al-qalam al-‘arabî, 2005, p. 142-14, 145.

31

Muslim, Sahîh, Cairo, Matbû‘at Muhammad ‘Alî Subayh, 1940, no. 3416, 7562, 7575, 7577. Mansûr, ‘Abd al-Bâqî Mansûr, Mawsû‘at ‘alâmât al-sâ‘a, Aleppo, Dâr al-Rifâ‘î and Dâr al-qalam al-‘arabî, 2005, p. 209-210.

32

‘Abd al-Bâqî Mansûr, Mawsû‘at ‘alâmât al-sâ‘a, Aleppo, Dâr al-Rifâ‘î and Dâr al-qalam al-‘arabî, 2005, p. 158-163, 254-255.

33

Abû al-Ma‘âlî al-Maqdisî, Fadâ’il Bayt al-Maqdis wa-al-Khalîl wa-Fadâ’il al-Shâm (ed. O. Livne-Kafri), Shfaram, Elmashreq, 1995, p. 320.

34

“‘Alay-kum bi-al-Shâm”, Muslim, Sahîh, Cairo, Matbû‘at Muhammad ‘Alî Subayh, 1940, no. 7560; Tirmidhî, Sunan, Beirut, Dâr ihyâ al-turâth al-‘arabî, undated, no. 2217; al-Hâkim al-Naysâbûrî, al-Hâkim al-Naysâbûrî, Al-Mustadrak ‘alâ al-sahîhayn, Beirut, Dâr al-kutub al-‘ilmiyya, 1990, no. 8426; Abû al-Ma‘âlî al-Maqdisî, Fadâ’il Bayt al-Maqdis wa-al-Khalîl wa-Fadâ’il al-Shâm (ed. O. Livne-Kafri), Shfaram, Elmashreq, 1995, p. 310-313, 325.

35

Soufis’ tradition, conveyed by popular beliefs, asseses that an invisible and small mystics’ community completes the ideal of holiness that God requires from humanity. They are called Abdâl – substitutes. If they were not alive on earth, God would not maintain sinner humanity alive and the world would disappear. Therefore they are considered as protectors, particularly in the places where they live.

36

Abû al-Ma‘âlî al-Maqdisî, Fadâ’il Bayt al-Maqdis wa-al-Khalîl wa-Fadâ’il al-Shâm (ed. O. Livne-Kafri), Shfaram, Elmashreq, 1995, p. 310-312, 319-323; where Syria is the antithesis to Iraq. On the presence of the Abdâl in Syria, see Tirmidhî al-Hakîm, Nawâdir al-usûl, Beirut, Dâr al-Jîl, 1992, vol. I, p. 21, 263; vol. III, p. 63.

37

Ibn Mâja, Sunan, Maktabat Abî al-Ma‘âtî, place of publication not indicated, undated, op. cit., no. 4082-4086; al-Hâkim al-Naysâbûrî, al-Hâkim al-Naysâbûrî, Al-Mustadrak ‘alâ al-sahîhayn, Beirut, Dâr al-kutub al-‘ilmiyya, 1990, no. 8670, 8673, 8675. It is worth noting that both Bukhârî and Muslim do not even recognise the name ”Mahdî”.

38

Muslim, Sahîh, Cairo, Matbû‘at Muhammad ‘Alî Subayh, 1940, n° 7560.

39

Muslim, Sahîh, Cairo, Matbû‘at Muhammad ‘Alî Subayh, 1940, no. 412, 7460, 7560. There is sometimes mention of a single successor to Jesus before the definitive End of the world.

40

“Lâ Mahdiyya illâ ‘Îsâ ibn Maryam”: Ibn Mâja, Sunan, Maktabat Abî al-Ma‘âtî, place of publication not indicated, undated, op. cit., no. 4039; Michel Hayek, Le Christ de l’Islam, Paris, Seuil, 1959, p. 246; Ibn Khaldoun, Ibn Khaldoun, Discours sur l’Histoire universelle. Al-Muqaddima (trad. V. Monteil), Paris, Sindbad, 1967-1968, vol. II p. 659-660.

41

Michel Hayek, Le Christ de l’Islam, Paris, Seuil, 1959, p. 254-255

42

Tirmidhî, Sunan, Beyrouth, Dâr ihyâ al-turâth al-‘arabî, s.d., n° 2253 ; ‘Abd al-Bâqî Mansûr, Mawsû‘at ‘alâmât al-sâ‘a, Alep, Dâr al-Rifâ‘î et Dâr al-qalam al-‘arabî, 2005, p. 210-212 ; Michel Hayek, Le Christ de l’Islam, Paris, Seuil, 1959, p. 249.

43

Abû al-Ma‘âlî al-Maqdisî, Fadâ’il Bayt al-Maqdis wa-al-Khalîl wa-Fadâ’il al-Shâm (ed. O. Livne-Kafri), Shfaram, Elmashreq, 1995, p. 211-213, 327.

44

‘Abd al-Bâqî Mansûr, Mawsû‘at ‘alâmât al-sâ‘a, Aleppo, Dâr al-Rifâ‘î and Dâr al-qalam al-‘arabî, 2005, p. 144-145, 153; Michel Hayek, Le Christ de l’Islam, Paris, Seuil, 1959, p. 247-249; 256. Cf. the book of Isaiah, chapter 11.

45

Muslim, Sahîh, Cairo, Matbû‘at Muhammad ‘Alî Subayh, 1940, no. 7568; Michel Hayek, Le Christ de l’Islam, Paris, Seuil, 1959, p. 265.

46

Abû al-Ma‘âlî al-Maqdisî, Fadâ’il Bayt al-Maqdis wa-al-Khalîl wa-Fadâ’il al-Shâm (ed. O. Livne-Kafri), Shfaram, Elmashreq, 1995, p. 211.

47

Studied by David Cook, Contemporary Muslim Apocalyptic Literature, Syracuse, Syracuse University Press, 2005.

Bibliographie

Mohammad Ali Amir-Moezzi, La Religion discrète. Croyances et pratiques spirituelles dans l’Islam shiite, Paris, Vrin, 2006.

Mohammad Ali Amir-Moezzi, “‘Alî et le Coran”, Revue des sciences philosophiques et théologiques, t. 98, 2014, p. 669-704.

Jean-Christophe Attias, Pierre Gisel, Lucie Kaennel (dir.), Messianismes. Variations sur une figure juive, Genève, Labor et Fides, 2000.

Emma Aubin-Boltanski, Claudine Gauthier (dir.), Penser la fin du monde, Paris, CNRS Éditions, 2014.

Muhammad al-Barzanjî, Al-ishâ‘a fî ashrât al-sâ‘a, Sayda-Beyrouth, al-Maktaba al-‘asriyya, 2005.

Bukhârî, al-Jâmi‘ al-sahîh, Le Caire, Dâr al-sha‘b, 1987.

Paul Casanova, Mohammad et la fin du monde, Paris, 1913.

Mark Cohen, Peter Schäfer (dir.), Toward the Millenium. Messianic Expectations from the Bible to Waco, Leiden, Brill, 1998.

David Cook, Studies in Muslim Apocalyptic, Princeton, Darwin Press, 2003.

David Cook, Contemporary Muslim Apocalyptic Literature, Syracuse, Syracuse University Press, 2005.

Mircea Eliade, Le Mythe de l’éternel retour. Archétypes et répétitions, Paris, Gallimard, 1969.

Hâkim al-Naysâbûrî, Al-Mustadrak ‘alâ al-sahîhayn, Beyrouth, Dâr al-kutub al-‘ilmiyya, 1990.

Michel Hayek, Le Christ de l’Islam, Paris, Seuil, 1959.

Ibn Hanbal, Musnad, Le Caire, Mu’assasat Qurtuba, s.d.

Ibn Khaldoun, Discours sur l’Histoire universelle. Al-Muqaddima, (trad. V. Monteil), Paris, Sindbad, 1967-1968 (3 vol.).

Ibn Mâja, Sunan, Maktabat Abî al-Ma‘âtî, s.l., s.d.

Pierre Lory, Min ta’rîkh al-hirmisiyya fî al-islâm, Jbeil, Byblion, 2005.

‘Abd al-Bâqî Mansûr, Mawsû‘at ‘alâmât al-sâ‘a, Alep, Dâr al-Rifâ‘î et Dâr al-qalam al-‘arabî, 2005.

Abû al-Ma‘âlî al-Maqdisî, Fadâ’il Bayt al-Maqdis wa-al-Khalîl wa-Fadâ’il al-Shâm (éd. O. Livne-Kafri), Shfaram, Elmashreq, 1995.

Muslim, Sahîh, Le Caire, Matbû‘at Muhammad ‘Alî Subayh, 1940.

Gershom Scholem, Le Messianisme juif. Essais sur la spiritualité du judaïsme, Paris, Calmann-Lévy, 1974.

Gershom Scholem, Sabbataï Tsevi. Le messie mystique, 1626-1676, Lagrasse, Verdier, 2008.

Suyûtî al-, Jésus, l’antéchrist et la fin du monde. Nuzûl ‘Îsâ ibn Maryam, (trad. anonyme), Lyon, Alburda, 2000.

Tirmidhî, Sunan, Beyrouth, Dâr ihyâ al-turâth al-‘arabî, s.d.

Tirmidhî al-Hakîm, Nawâdir al-usûl, Beyrouth, Dâr al-Jîl, 1992.