( College of William & Mary)

Today, Maroons – self-liberated slaves and their descendants – still form semi-independent communities in several parts of the Americas, for example, in Suriname, French Guiana, Jamaica, Belize, Colombia, and Brazil. As the most isolated of Afro-Americans, they have since the 1920s been an important focus of scientific research, contributing to theoretical debates about slave resistance, the heritage of Africa in the Americas, the process of creolization, and the nature of historical knowledge among nonliterate peoples1.

Communities formed by Maroons dotted the fringes of plantation America, from Brazil to Florida, from Peru to Texas. The English word “Maroon”, like the French marron derives from Spanish cimarrón, itself based on an Arawakan [Taino] Indian root2. Cimarrón originally referred to domestic cattle that had taken to the hills in Hispaniola, and soon after it was applied to American Indian slaves who had escaped from the Spaniards. By the end of the 1530s, the word was being used primarily to refer to Afro-American runaways and had strong connotations of “fierceness”, of being “wild” and “unbroken”3.

The Unknown Maroon (carved by Albert Mangonès, ca. 1971), in front of Haiti's National Palace.

Marronage: a transatlantic history

Maroon communities, called palenques in the Spanish colonies and mocambos or quilombos in Brazil, ranged from tiny bands that survived less than a year to powerful states encompassing thousands of members that lasted for generations or in some cases centuries. Maroons and their communities can be seen to hold a special significance for the study of Afro-American societies. While they were, from one perspective, the antithesis of all that slavery stood for, they were also a widespread and embarrassingly visible part of these systems. Just as the very nature of plantation slavery implied violence and resistance, the wilderness setting of early New World plantations made marronage and the existence of organized Maroon communities a ubiquitous reality.

Marronage was also a response to enslavement in Africa in the wake of the internecine wars fostered by the Atlantic slave trade4. Fugitives from the chaos and violence that dominated much of West Central Africa, including runaways from slave coffles during the seventeenth- and eighteenth- century expansion of the trade, frequently founded Maroon settlements in marginal areas. Some had populations of several hundreds, lived by raiding more settled groups, or even fought against their former masters. But all remained sufficiently caught up in the political ebb and flow of the era that they did not maintain separate Maroon identities for more than a generation or two. During the eighteenth century, fugitives from the trade along the Upper Guinea coast also formed Maroon communities, sometimes on islands just offshore, but mass recapture after months or years was the norm.

In the Americas, the meaning and attractiveness of marronage differed for enslaved people in different social positions, varying with their perceptions of themselves and their situations, which were influenced by diverse factors such as their places of birth, the periods of time they had been in the New World, their task assignments as slaves, their family responsibilities, and the particular treatments they were receiving from overseers or masters, as well as more general considerations such as the proportions of Blacks to Whites in the region, the proportions of freedmen in the population, the natures of available terrain in which to establish communities, and the opportunities for manumission. Many Maroons, particularly men, escaped during their first hours or days in the Americas. Enslaved Africans who had already spent some time in the New World seem to have been less prone to flight. But Creole slaves who were particularly acculturated, who had learned the ways of the plantation best, seem to have been highly represented among runaways, often escaping to urban areas where they could pass as free because of their independent skills and ability to speak the colonial language.

The large number of detailed newspaper advertisements for runaway slaves placed by masters attests to the high level of planter concern, while at the same time affording the critical historian an important set of sources for establishing the profiles of Maroons, which varied significantly by historical period and country. Individual Maroons fled not only to the hinterlands – many, especially skilled slaves, escaped to urban centers and successfully melted into the population of freedmen – but also became maritime Maroons, fleeing by fishing boat or other vessel across international borders. In Haiti, Maroons played a signal role as catalysts in the Haitian Revolution that created the first nation in the Americas in which all citizens were free.

During the past several decades, anthropological fieldwork has underlined the strength of historical consciousness among the descendants of these rebel slaves and the dynamism and originality of their cultural institutions. Meanwhile, historical scholarship on Maroons has flourished, as new research has done much to dispel the myth of the docile slave. The extent of violent resistance to enslavement has been documented rather fully – from the revolts in the slave factories of West Africa and mutinies during the Middle Passage to the organized rebellions that began to sweep most colonies within a decade after the arrival of the first slave ships. And there is a growing literature on the pervasiveness of various forms of “day‑to‑day” resistance – from simple malingering to subtle but systematic acts of sabotage.

Marronage represented a major form of slave resistance, whether accomplished by lone individuals, by small groups, or in great collective rebellions. Throughout the Americas, Maroon communities stood out as a heroic challenge to white authority, as the living proof of the existence of a slave consciousness that refused to be limited by the Whites’ conception or manipulation of it. It is no accident that throughout the Caribbean today, the historical Maroon – often mythologized into a larger-than-life figure – has become a touchstone of identity for the region’s writers, artists, and intellectuals, the ultimate symbol of resistance and the fight for freedom.

Planters generally tolerated “petit marronage” – truancy with temporary goals such as visiting a friend or lover on a neighboring plantation. But in most slave-holding colonies, the most brutal punishments – amputation of a leg, castration, suspension from a meat hook through the ribs, slow roasting to death – were reserved for long-term, recidivist Maroons, and in many cases these were quickly written into law.

“A Negro hung alive by the Ribs to a Gallows”,

“The Execution of Breaking on the Rack”,

“Flagellation of a Female Samboe Slave”,

Engravings by William Blake (1770s). From John Gabriel Stedman, Narrative of a Five Years Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, London, Joseph Johnson, 1796, hand-colored edition (collection of Richard and Sally Price).

It was marronage on the grand scale, with individual fugitives banding together to create communities, that struck directly at the foundations of the plantation system, presenting military and economic threats that often taxed the colonists to their very limits. Maroon communities, whether hidden near the fringes of the plantations or deep in the forest, periodically raided plantations for firearms, tools, and enslaved women, often permitting families that had formed during slavery to be reunited in freedom.

Patchwork cape sewn ca. 1910 by Peeepina (Ndyuka from the village of Totikampu) for her husband Agbago Aboikoni, who later became Saamaka Paramount Chief.

Collection Richard and Sally Price.

From Sally Price & Richard Price, Les Arts des Marrons, p. 90.

To be viable, Maroon communities had to be inaccessible, and villages were typically located in remote, inhospitable areas. In the southern United States, isolated swamps were a favorite setting, and Maroons often became part of Native American communities5. In Jamaica, some of the most famous Maroon groups lived in the intricately accidented “cockpit country,” where water and good soil are scarce but deep canyons and limestone sinkholes abound. In the Guianas, seemingly impenetrable jungles provided Maroons with a safe haven.

Successful Maroon communities learned quickly to turn the harshness of their immediate surroundings to their own advantage for purposes of concealment and defense. Paths leading to the villages were carefully disguised, and much use was made of false trails replete with dangerous booby traps. In the Guianas, villages set in swamps were approachable only by an underwater path, with other, false, paths carefully mined with pointed spikes or leading only to fatal quagmires or quicksand. In many regions, man traps, or even dog traps, were used in village defenses.

Throughout the hemisphere, Maroons developed extraordinary skills in guerrilla warfare. To the bewilderment of their colonial enemies, who attempted to employ rigid and conventional tactics learned on the open battledfields of Europe, these highly adaptable and mobile warriors took maximum advantage of confined environments, striking and withdrawing with great rapidity, making extensive use of ambushes to catch their adversaries in cross fire, fighting only when and where they chose, depending on reliable intelligence networks among non-Maroons (both slaves and white settlers), and often communicating by drums and horns.

“March thro’ a swamp or Marsh in Terra firma”,

“A Rebel Negro armed & on his guard”,

Engravings by William Blake (1770s). From John Gabriel Stedman, Narrative of a Five Years Expedition against the Revolted Negroes of Surinam, London, Joseph Johnson, 1796, hand-colored edition (collection of Richard and Sally Price).

In many cases, the beleaguered colonists were eventually forced to sue their former slaves for peace. In Brazil, Colombia, Cuba, Ecuador, Hispaniola, Jamaica, Mexico, Panama, Peru, Suriname, and Venezuela, for example, the whites reluctantly offered treaties granting Maroon communities their freedom, recognizing their territorial integrity, and making some provision for meeting their economic needs, in return for an end to hostilities toward the plantations and an agreement to return future runaways6. Of course, many Maroon societies were crushed by massive force of arms, and even when treaties were proposed they were sometimes refused or quickly violated. Nevertheless, new Maroon communities seemed to appear almost as quickly as the old ones were exterminated, and they remained, from a colonial perspective, the “chronic plague” and “gangrene” of many plantation societies right up to final emancipation7.

Maroon communities’ originality and dynamism

Today, the relationships between Maroon communities and the nation-states in which they live vary broadly. In much of Brazil or even Jamaica, communities remain proud of their Maroon heritage but, to an outsider, seem little different from the non-Maroon rural population that surrounds them. In contrast, along the rivers of Suriname, Maroons live in villages that outsiders often compare to precolonial Africa, where everything from language, dress, kinship, transportation, and laws are unique Maroon creations that instantly differentiate the population from others in the country. The tension between Maroon identity and national identity has become acute for many younger people who have moved from traditional territories to cities or even to foreign countries. Yet in some areas, such as the Saamaka villages along the Suriname river, both Maroon culture and identity remain vibrant8.

Sepu (leg accessory), 1950's : accessory worn by many until the 1970's among the Saamaka Maroons from Suriname; today, worn for funerals or for New Year's fest (See the Amazonian Museum Network's website).

The initial Maroons in any New World colony hailed from a wide range of societies in West and Central Africa – at the outset, they shared neither language nor other major aspects of culture. Their collective task, once off in the forests or mountains or swamplands, was nothing less than to create new communities and institutions, largely via a process of inter-African cultural syncretism. Those scholars, mainly anthropologists, who have examined contemporary Maroon life most closely seem to agree that such societies are often uncannily “African” in feeling but at the same time largely devoid of directly transplanted systems. However “African” in character, no Maroon social, political, religious, or aesthetic system can be reliably traced to a specific African ethnic provenience – they reveal, rather, their hybrid composition, forged in the early meeting of peoples of diverse African, European, and Amerindian origins in the dynamic setting of the New World9.

For example, the political system of the great seventeenth-century Brazilian Maroon kingdom of Palmares, which R.K. Kent characterized as an “African” state, “did not derive from a particular Central African model, but from several”10. In the development of the kinship system of the Ndyuka Maroons of Suriname, writes André Köbben, “undoubtedly their West-African heritage played a part ... [and] the influence of the matrilineal Akan tribes is unmistakable, but so is that of patrilineal tribe... [and there are] significant differences between the Akan and Ndyuka matrilineal systems”11. Historical and anthropological research has revealed that the magnificent woodcarving of the Suriname Maroons, long considered “an African art in the Americas” on the basis of formal resemblances, is in fact a fundamentally new, Afro-American art “for which it would be pointless to seek the origin through direct transmission of any particular African style”12. And detailed investigations – both in museums and in the field – of a range of cultural phenomena among the Maroons of Suriname and French Guiana have confirmed the dynamic, creative processes that continue to animate these societies13.

Saamaka interior door carved ca. 1930 by Heintje Schmidt, village of Ganzee.

Surinaams Museum, Paramaribo.

From Sally Price & Richard Price, Les Arts des Marrons, p. 106.

Maroon cultures do possess direct and sometimes spectacular continuities from particular African peoples, from military techniques for defense to recipes for warding off sorcery14. These are, however, of the same type as those that can be found, albeit with lesser frequency, in Afro-American communities throughout the hemisphere. In stressing these isolated African “retentions,” there is a danger of neglecting cultural continuities of a more significant kind.

Roger Bastide divided Afro-American religions into those he considered “preserved” or “canned” – like Brazilian Candomblé – and those that he considered “alive” – like Haitian Vaudou. The former, he argued, manifest a kind of “defense mechanism” or “cultural fossilization,” a fear that any small change may bring on the end, while the latter are more secure of their future and freer to adapt to the changing needs of their adherents15. Although he considerably oversimplified, it does seem that tenacious fidelity to “African” forms, in many cases, does indicate a culture finally having lost meaningful touch with the vital African past. Certainly, one of the most striking features of West and Central African cultural systems is their internal dynamism, their ability to grow and change.

The cultural uniqueness of the more developed Maroon societies (e.g., those in Suriname) rests firmly on their fidelity to “African” cultural principles at these deeper levels – whether aesthetic, political, religious, or domestic – rather than on the frequency of their isolated “retentions.” With a rare freedom to extrapolate ideas from a variety of African societies and adapt them to changing circumstances, Maroon groups included (and continue to include today) what are in many respects at once the most meaningfully “African” and the most truly “alive” and culturally dynamic of all Afro-American cultures.

Son Palenque. Songs by the Afro-Colombian band "Son Palenque".

Images & Edit by Vincent Moon Sound & Mix by Andres Velasquez

Produced by Vincent Moon and Lulacruza

Examples of Maroons communities in the Americas

The most famous Maroon societies in the history of the Americas are Palmares in Brazil, Palenque de San Basilio in Colombia, the communities in Esmeraldas, Ecuador, the Mexican Maroons of San Lorenzo de los Negros, the Maroons of Jamaica, and the Saamaka and Ndyuka Maroons of Suriname.

Palmares, in northeastern Brazil, flourished for a full century before its final defeat by a large Portuguese army in 1694–95. A close-knit federation of villages made up of some 11,000 people, largely Angolan-born Africans, it also included some Brazilian Indians, poor whites, and Portuguese deserters. During the seventeenth century, wave after wave of Dutch and then Portuguese armies was sent out against Palmares, which resisted with the help of its complex political and social organization, under the leadership of Ganga Zumba and, during its final years, the legendary Zumbi. Knowledge of the internal affairs of Palmares remains limited, based as it is on soldiers’ reports, the testimony of a captive under torture, official documents, archaeological work, and the like. But as a modern symbol of black (and anticolonial) heroism, Palmares continues to evoke strong emotions in Brazil and serve as the touchstone of the Black Movement16.

Zumbi's Bust in Brasilia, Brazil. With the inscription: "Zumbi dos Palmares, Black leader of all races".

El Palenque de San Basilio boasts a history stretching back to the seventeenth century. In recent years, historians, anthropologists, and linguists – working in collaboration with Palenqueros – have uncovered a great deal about continuities and changes in the life of these early Colombian freedom fighters, whose proud descendants still occupy the town today17.

Palenqueros, San Basilio de Palenque, Colombia. See Forum of Biodiversity.

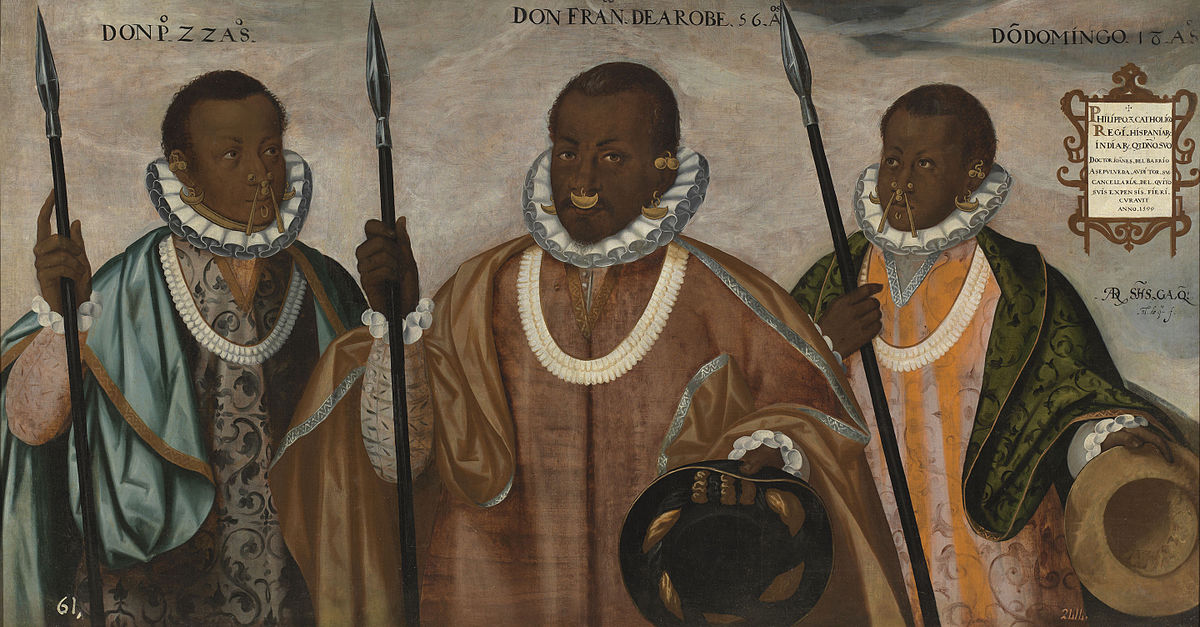

The Maroon history of Esmeraldas, on the Pacific coast of Ecuador, and neighboring Barbacoas in Colombia, began in the early sixteenth century, when Spanish ships carrying African slaves from Panama to Guayaquil and Lima were wrecked amidst strong currents. A number of slave survivors sought freedom in the unconquered interior, where they allied with indigenous peoples. In the 1580s, having beaten back military expeditions sent to capture them, several Maroon leaders traveled to Quito to make peace with the Spanish. In 1599, a famous portrait of one such leader, Don Francisco de Arobe, and his two sons, was commissioned and sent to Philip III of Spain as a coronation gift and to commemorate these negotiations. Later, these Maroons were joined by rebel slaves from highland haciendas and lowland mines and formed a number of free towns, even as slavery continued nearby18.

The Mulattos of Esmeraldas, by Andrés Sánchez Gallque, 1599.

The remarkable gold ornaments worn by the three men in the painting are from ancient indigenous sites in Maroon territory, where they dug up and reused the Amerindian jewelry.

San Lorenzo de los Negros, in Veracruz on the Caribbean coast of Mexico, is probably the best known of the seventeenth-century Maroon towns in Mexico. Under their leader Yanga, these Maroons attempted to make peace as early as 1608, but it was not till 1630, after years of intermittent warfare, that the Viceroy and the crown finally agreed to establish the town of free Maroons19.

The Jamaica Maroons, who continue to live in two main groups centered in Accompong (in the hills above Montego Bay) and in Moore Town (deep in the Blue Mountains), maintain strong traditions about their days as freedom fighters, when the former group was led by Cudjoe and the latter by the redoubtable woman warrior Nanny (whose likeness now graces the Jamaican 500-dollar bill). Two centuries of scholarship, some of it written by Maroons themselves, offers diverse windows on the ways these men and women managed to build a vibrant culture within the confines of a relatively small island20.

The Kindah Tree of Accompong near where the Maroons signed their treaty with the British in 1739.

The Suriname Maroons constitute the most fully documented case of how former slaves built new societies and cultures under conditions of extreme deprivation in the Americas and how they developed and maintained semi-independent societies that persist in the present. From their late seventeenth-century origins and the details of their wars and treaty making to their current struggles with multinational mining and timber companies, a great deal is now known about these peoples’ achievements, in large part because of the extensive recent collaboration by Saamaka and Ndyuka Maroons with anthropologists. Today, Suriname Maroons – who number some 210,000 people – live in the interior of the country, in and around the capital Paramaribo, and in neighboring French Guiana as well as in the Netherlands21. The relevant bibliographic resources number in the thousands22.

Rickman G-Crew, “Je suis un Boni/Aluku”, Official Videoclip, 2016.

Our first detailed outsiders’ view of what Saamaka life looked like dates from the middle of the eighteenth century, thanks to the detailed diaries of the German Moravian missionaries who were sent out to live in Saamaka villages right after the 1762 peace treaty23. What we learn is that Saamaka life, including religion, language, politics, and much else, was already in its main lines very similar to its present form, with frequent spirit possession and other forms of divination, matriliny, polygyny, a strong ancestor cult, institutionalized cults for the gods encountered in the forest and the river, and a variety of gods of war. But even the great Saamaka war óbias (magical powers), including those with names that point to a particular African people or place such as Komantí, were in fact radical blends of several African traditions, largely developed in Suriname via processes of communal divination. By the time Saamakas had signed their peace treaty with the Dutch crown after nearly a century of guerrilla warfare, in 1762, there were few African‑born Saamakas still alive and their culture already represented an integrated, highly developed African‑American synthesis whose main processual motor had been inter‑African syncretism.

Rather than merely blending into the surrounding populations after the emancipation of slaves (as happened in so many places elsewhere in the Americas), the Marrons of Suriname (many of whom now live in French Guiana) continue today to display a remarkable degree of cultural difference from surrounding populations. A number of images that attest to this cultural difference in daily life as well as the arts can be found in our publications24.

Calabash container with wooden handle carved by an Aluku man (collected 1932, now in the Tropenmuseum, Amsterdam);

Calabash carved by a Saamaka woman named Kekeete, village of Asindoopo (collected 1968, now in the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, New York).

From Sally Price & Richard Price, Les Arts des Marrons, p. 148.

Academic debates about marronage

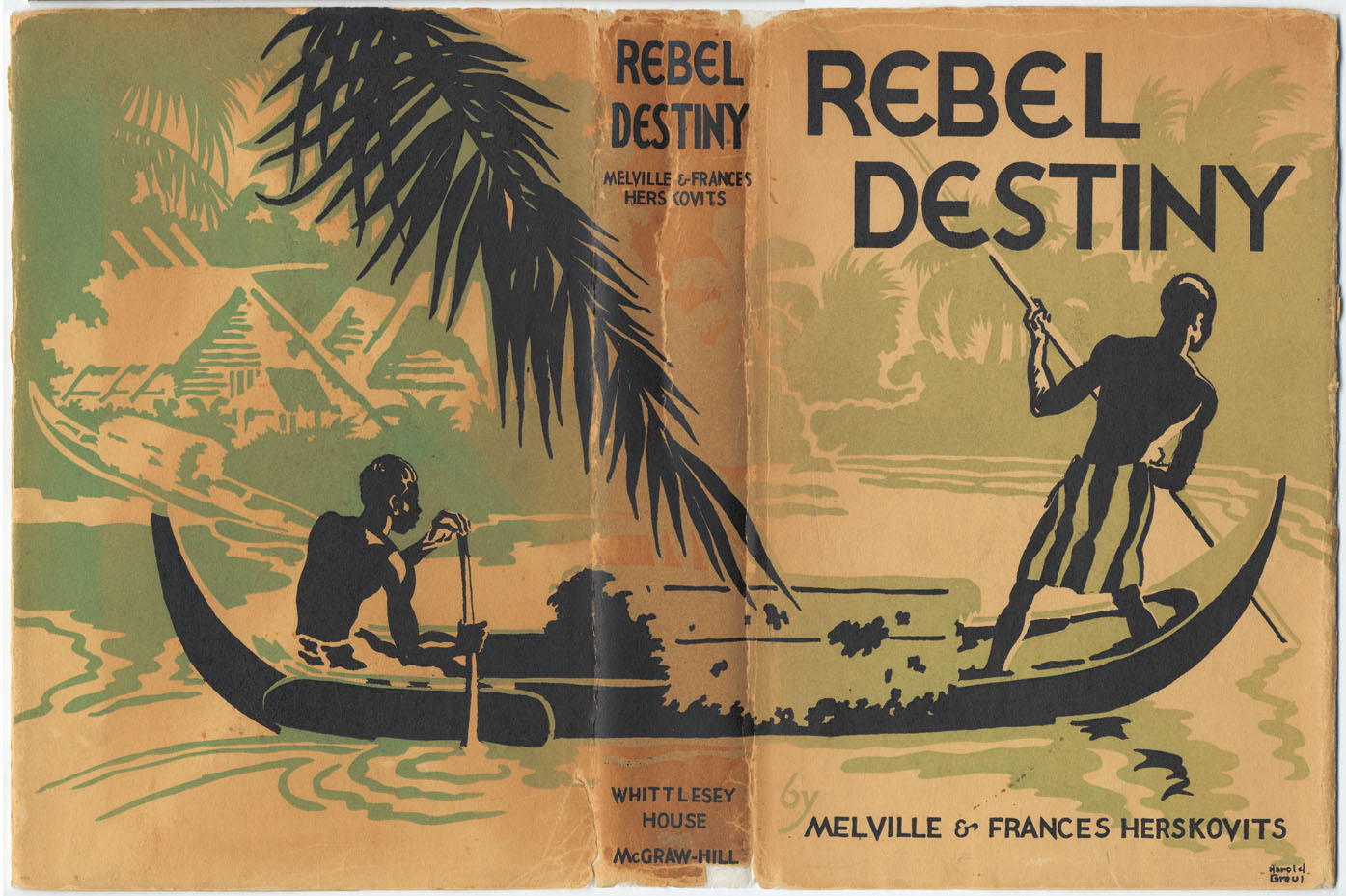

Since Melville and Frances Herskovits’s first foreign fieldwork, with Saamaka Maroons during the summers of 1928 and 1929, Maroons (in particular, the Saamaka) have moved to the center of anthropological debates, from the origins of Creole languages and the “accuracy” of oral history to the nature of the African heritage in the Americas and the very definition of Afro-American anthropology.

Book cover of Rebel Destiny by Melville and Frances Herskovits (New York, London: Whittlesey House, McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1934)

The Saamaka fieldwork played a signal role in Melville Herskovits’s career, exercising – in the words of his widow – “a profound influence on his thinking”:

In the Guiana bush ... he saw, as he often told his students, nearly all of sub-Saharan Africa represented, from what is now Mali to Loango and into the Congo – and the Loango chief who came to our base camp [in Saamaka territory] invoked both the Great God of the Akan of the Gold Coast, Nyankompon, and the Bantu Zambi25.

During that Maroon research, and on the voyages to and from Suriname, Herskovits developed a comparative vision of Afro-American studies (and of the Caribbean as “a social laboratory”) that would fuel his own prodigious work, and that of countless students, for decades to come. The seeds of his interest in exploring the African provenience of New World Negroes, in establishing an historical-ethnographic baseline in Africa for the study of New World developments, and in analyzing processes of cultural change (such as ‘acculturation,’ ‘reinterpretation,’ and ‘syncretism’) were all sown during this early fieldwork26.

The expansion and critique of Herskovits’ work, especially the controversial essay by Sidney W. Mintz and Richard Price27 and the reactions to it, have kept Maroons at the center of debate among Afro-Americanist anthropologists and historians28. Indeed, David Scott argues that the Saamaka Maroons have by now become “a sort of anthropological metonym – providing the exemplary arena in which to argue out certain anthropological claims about a discursive domain called Afro-America”29.

Much of the recent anthropological research among Maroons has focused on historiography and historical consciousness – how Maroons themselves conceptualize and transmit knowledge about the past – and it has privileged the voices of individual Maroon historians. First-Time30 presented oral historical accounts by Saamakas of the early years of their society’s formation, 300 years ago, including their rebellions from slavery and their battles against the colonists. Its sequel, Alabi’s World supplemented these Saamaka accounts with archival materials from German missionaries and Dutch administrators who lived in Saamaka villages beginning right after the 1762 peace treaties with the colonists, directly juxtaposing ever more complex written and oral materials about the same events31. Kenneth M. Bilby’s True-Born Maroons combined oral and archival materials, with an emphasis on the perspective of Maroons themselves, for Jamaica, uncovering a remarkable number of African practices as well as a great deal of early New World creolization, involving language, religious practices, and much else32. A recent history in Dutch of the first century of Ndyuka Maroons presents alternating chapters based on oral and archival materials, creating a rich historical picture of politics and social life in this Suriname Maroon society33.

Taken together, these studies helped pioneer the complementary use of oral history and archival research in the disciplines of anthropology and history more generally. They have caused significant chinks in traditional historians’ reluctance to take oral data as seriously as written materials. Not surprisingly, this type of work has occasionally raised the charge of “verificationism” from post-modernist scholars34 but the particular kinds of attention it shows to the politics of memory – the strategic use of archival materials to complement Maroon narratives – can be defended as a decisive and progressive political act, one intended in part to foster social justice, rather than being judged as naive or politically retrograde35.

Recent anthropological research has also focused on the ongoing debate about “creolization” and the extent to which (and the ways in which) Maroons and other African-Americans have drawn, on the one hand, upon their diverse African heritages and, on the other hand, upon their New World experiences and their own creativity in building their cultural worlds. Researchers have been asking how, in each New World colony, enslaved Africans, coming from a variety of nations and languages, became African-Americans. Scholars have found that to begin to explore these processes, across the many regions where Africans were landed as captive laborers, one must first ask: How “ethnically” homogeneous (or heterogeneous) were the Africans who arrived in a particular New World locality – in other words, to what extent was there a clearly dominant group – and what were the cultural consequences? How quickly and in what ways did they and their African- American offspring begin thinking and acting as members of new communities? In what ways did the African arrivants choose – and to what extent were they able – to continue particular ways of thinking and doing things that came from the Old World? What did “Africa” (or its subregions and peoples) mean at different times to African arrivants and their descendants? How did the various demographic profiles and social conditions of particular New World settings encourage or inhibit these cultural processes? In short, what is it that made what Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot called “the miracle of creolization”36possible, across the Americas, over and over again?

Maroon societies play a privileged role in such discussion, in part owing to their relative isolation and, in the case of Suriname and French Guiana, their persistence into the present. The most detailed ethnography of creolization to date analyzes extensive data from esoteric Maroon languages, as well as other ritual materials, to demonstrate the complexity of these issues from both an ethnohistorical perspective and that of Maroons themselves37. Eric Hobsbawm, commenting on the significance of this kind of work in the more general context of the social sciences, notes that “Maroon societies raise fundamental questions. How do casual collections of fugitives of widely different origins, possessing nothing in common but the experience of transportation in slave ships and of plantation slavery, come to form structured communities? How, one might say more generally, are societies founded from scratch? What exactly did or could such refugee communities ... derive from the old continent?”38 Questions such as these are sure to keep students of Maroon societies engaged in active research for many years to come.

Recent struggles for sovereignty and land rights

Since the turn of the twenty-first century, Maroons have taken center stage in the struggle for territory and sovereignty within nation-states, particularly in Brazil and in Suriname. Following promulgation of the new constitution of Brazil in 1988 (and subsequent reforms), the descendants of historical quilombos (which originally meant ‘Maroon communities’) have, under certain conditions, had the right to claim collective title to the lands on which their ancestors lived. In the process of the ensuing legal battles, the definition of quilombo has expanded to include almost any landless black Brazilian community, rural or urban, whose members can claim a history of resistance to state power – not just descendants of Maroons. Today, many young Brazilian anthropologists are trained explicitly to help such quilombo-descendant communities in their quest for title to lands and related rights39.

In 1990’s Suriname, the Saamaka Maroons–then some 80,000 people – found the lands that their ancestors had lived on since the late seventeenth century invaded by Chinese loggers and other multinational mining and extraction companies that had received permits from the national government. Suriname’s postcolonial constitution grants ownership of the forest, which is inhabited by a number of indigenous peoples as well as six Maroon peoples, to the State, which during that decade began doling out mining and logging concessions to foreign multinationals. Organizing themselves and obtaining legal aid, the Saamaka People fought a decade-long legal battle with the Republic of Suriname. This struggle culminated in a landmark 2007 judgment by the Inter-American Court for Human Rights (the case of “Saramaka People v Suriname”), requiring the nation to change its laws to grant the Saamaka people collective title to their traditional territory as well as considerable sovereignty over it – a judgment that establishes jurisprudence for indigenous peoples and Maroons throughout the Americas. Richard Price served as advisor and expert witness for the Saamaka during this case, providing an example of advocacy in anthropology and he later wrote a book the Saamaka struggle for their sovereignty40.

Inter-American Court for Human Rights, San José, Costa Rica.

Two lawyers – Elizabeth Abi-Mershed (Inter-American Commission of Human Rights) and Fergus MacKay (attorney for the Saamaka People) help prepare two witnesses (Richard Price and Headcaptain Wazen Eduards) the day before the trial, Costa Rica, 2007.

It is sad to have to report that as I write in 2018, the government of Suriname has continued to act as if the judgment of the court had never taken place – and its refusal to abide by the court’s decision increasingly makes the 2007 judgment look like a Pyrrhic victory. The rights of Saamakas, as well as other Suriname Maroons and indigenous peoples, remain today under serious threat, despite the continued efforts of the Saamakas, their lawyers, and the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights to persuade the government to comply with the orders of the court.

Notes

1

This article borrows from numerous of my previous publications, beginning with the long introduction to my first book, Maroon Societies: Rebel Slave Communities in the Americas, New York, Doubleday/Anchor, 1973. Other relevant works can be found at www.richandsally.net.

2

José Juan Arrom, “Cimmarón: Apuntes sobre sus primeras documentaciones y su probable origen”, in J.J. Arrom and M.A. García Arévalo (eds.), Cimmarón, Santo Domingo, Fundación García Arévalo, 1986, p. 13-30.

3

Georg Friederici, Amerikanistisches Wörterbuch und Hilfswörterbuch für den Amerikanisten, Hamburg, Cram, De Gruyter & Co., 1960, p. 191-192.

4

Joseph C. Miller, Way of Death: Merchant Capitalism and the Angolan Slave Trade, 1730-1830, Madison, University of Wisconsin Press, 1998.

5

See, for example, Sylviane A. Diouf, Slavery’s Exiles: The Story of the American Maroons, New York, NYU Press, 2013.

6

Kenneth M. Bilby, “Swearing by the Past, Swearing to the Future: Sacred Oaths, Alliances, and Treaties among the Guianese and Jamaican Maroons”, Ethnohistory, vol. 44, nᵒ 4, 1997, p. 655-689.

7

Yvan Debbasch, “Le marronnage : essai sur la désertion de l’esclave antillais”, L’Année Sociologique, 3e série, 1961, p. 1-112 ; 1962, p. 117-195, p. 124.

8

Richard Price and Sally Price, Saamaka Dreaming, Durham NC, Duke University Press, 2017.

9

Richard Price, Travels with Tooy: History, Memory, and the African American Imagination, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2008.

10

R.K., Kent, “Palmares: An African State in Brazil”, Journal of African History, nᵒ 6, 1965, p. 165-175, p. 175.

11

André J.F. Köbben, “Unity and Disunity: Cottica Djuka Society as a Kinship System”, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, nᵒ 123, 1967, p. 10-52, p. 14.

12

Jean Hurault, Africains de Guyane: la vie matérielle et l’art des Noirs Réfugiés de Guyane, La Haye-Paris, Mouton, 1970, p. 84.

13

Sally Price, Richard Price, Maroon Arts: Cultural Vitality in the African Diaspora, Boston, Beacon Press, 1999.

14

See, for example, Richard Price, Travels with Tooy: History, Memory, and the African American Imagination, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2008, p. 432.

15

Roger Bastide, African Civilizations in the New World, New York, Harper & Row, 1972, p. 128-151.

16

See, for example, João José Reis, Flávio dos Santos Gomes (eds.), Liberdade por um fio: Historia dos quilombos no Brasil, São Paulo, Companhia das Letras, 1996; and Flávio dos Santos Gomes, Palmares, São Paulo, Contexto, 2005.

17

See, for example, Armin Schwegler, Bryan Kirschen, Graciela Maglia (eds.), Orality, Identity, and Resistance in Palenque (Colombia): An Interdisciplinary Approach, Amsterdam, John Benjamins, 2017. For an illustrated introduction to this community, see Nina de Friedemann, Richard Cross, Ma ngombe: Guerreros y ganaderos en Palenque, Bogotá, Carlos Valencia Editores, 1979.

18

Kris Lane, Quito 1599: City and Colony in Transition, Albuquerque, University of New Mexico Press, 2002.

19

For a summary of Maroon communities in Mexico, see Joe Pereira, “Maroon Heritage in Mexico,” in E.K. Agorsah (ed.), Maroon Heritage: Archaeological, Ethnographic and Historical Perspectives, Kingston, Jamaica, Canoe Press, 1994, p. 94-107.

20

For the Maroons of Accompong, see Jean Besson, Transformations of Freedom in the Land of the Maroons: Creolization in the Cockpits of Jamaica, Kingston, Ian Randle, 2016; for the Windward Maroons (Nanny’s descendants), see Kenneth M. Bilby, True-Born Maroons, Gainesville, University Press of Florida, 2005.

21

Richard Price, “The Maroon Population Explosion: Suriname and Guyane”, New West Indian Guide, nᵒ 87, 2013, p. 323-327.

22

Good starting places are Richard Price and Sally Price, Saamaka Dreaming, Durham NC, Duke University Press, 2017; Richard Price and Sally Price, Les Marrons, Châteauneuf-le-Rouge, Vents d’ailleurs, 2003; and www.richandsally.net. See also Jean Moomou (ed.), Sociétés marronnes des Amériques: mémoires, patrimoines, identités et histoire du XVIIe au XXe siècles, Matoury, Guyane française, Ibis Rouge, 2015.

23

Richard Price, Alabi’s World, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990.

24

See, in particular, Sally Price, Richard Price, Les Arts des Marrons, La Roque d'Anthéron, Vents d’ailleurs, 2005; Richard Price, Travels with Tooy: History, Memory, and the African American Imagination, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2008; Richard Price, Sally Price, Saamaka Dreaming, Durham NC, Duke University Press, 2017. For some images on the web, see https://www.facebook.com/Fesiten ; https://www.facebook.com/Boo-go-a-Kontukonde-162476164189085/ ; https://www.facebook.com/rixsal/.

25

Frances S. Herskovits, “Introduction”, in F. S. Herskovits (ed.), The New World Negro, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1966, p. vii-viii.

26

Richard Price and Sally Price, The Root of Roots: Or, How Afro-American Anthropology Got Its Start, Chicago, Prickly Paradigm Press/University of Chicago Press, 2003.

27

Sidney W. Mintz, Richard Price, The Birth of African‑American Culture, Boston, Beacon Press, 1992 [1973].

28

Richard Price, “On the Miracle of Creolization”, in K.A. Yelvington (ed.), Afro-Atlantic Dialogues: Anthropology in the Diaspora, Santa Fe, SAR Press, 2006, p. 113-145.

29

David Scott, “That Event, This Memory: Notes on the Anthropology of African Diasporas in the New World”, Diaspora, nᵒ 1, 1991, p. 261-284, p. 269.

30

Richard Price, First‑Time: The Historical Vision of an Afro‑American People, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983 (now translated into the Saamaka language at the request of the Saamaka People as Fesiten [translated and adapted by Richard Price & Sally Price], La Roque d'Anthéron, Vents d’ailleurs, 2013).

31

Richard Price, Alabi’s World, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990.

32

Kenneth M. Bilby, True-Born Maroons, Gainesville, University Press of Florida, 2005.

33

H. U. E.Thoden van Velzen and Wim Hoogbergen, Een zwarte vrijstaat in Suriname: De Okaanse samenleving in de 18e eeuw, Leiden, KILTV, 2011.

34

David Scott, “That Event, This Memory: Notes on the Anthropology of African Diasporas in the New World”, Diaspora, nᵒ 1, 1991, p. 261-284.

35

Richard Price, “On the Miracle of Creolization”, in K.A. Yelvington (ed.), Afro-Atlantic Dialogues: Anthropology in the Diaspora, Santa Fe, SAR Press, 2006, p. 113-145.

36

Michel-Rolph Trouillot, “Culture on the Edges: Creolization in the Plantation Context”, Plantation Society in the Americas, vol. 5, nᵒ 1, 1998, p. 8-28, p. 8

37

Richard Price, Travels with Tooy: History, Memory, and the African American Imagination, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2008.

38

Eric Hobsbawm, “Escaped Slaves of the Forest”, New York Review of Books, December 6, 1990. p. 46-48, p. 46.

39

Richard Price, “Scrapping Maroon History: Brazil's Promise, Suriname's Shame”, New West Indian Guide, nᵒ 72, 1998, p. 233-255; Véronique Boyer, “Qu’est le quilombo aujourd’hui devenu ? De la catégorie coloniale au concept anthropologique”, Journal de la Société des Américanistes, vol.96, nᵒ 2, 2010, p. 229-251.

40

Richard Price, Rainforest Warriors: Human Rights on Trial, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011.

Bibliographie

José Juan Arrom, “Cimmarón: Apuntes sobre sus primeras documentaciones y su probable origen”, in J.J. Arrom and M.A. García Arévalo (eds.), Cimmarón, Santo Domingo, Fundación García Arévalo, 1986, p. 13-30.

Roger Bastide, African Civilizations in the New World, New York, Harper & Row, 1972.

Jean Besson, Transformations of Freedom in the Land of the Maroons: Creolization in the Cockpits of Jamaica, Kingston, Ian Randle, 2016.

Kenneth M. Bilby, “Swearing by the Past, Swearing to the Future: Sacred Oaths, Alliances, and Treaties among the Guianese and Jamaican Maroons”, Ethnohistory, vol. 44, nᵒ 4, 1997, p. 655-689.

Kenneth M. Bilby, True-Born Maroons, Gainesville, University Press of Florida, 2005.

Véronique Boyer, “Qu’est le quilombo aujourd’hui devenu ? De la catégorie coloniale au concept anthropologique”, Journal de la Société des Américanistes, vol.96, nᵒ 2, 2010, p. 229-251.

Yvan Debbasch, “Le marronnage: essai sur la désertion de l’esclave antillais”, L’Année Sociologique, 3e série, 1961, p. 1-112 ; 1962, p. 117-195.

Sylviane A. Diouf, Slavery’s Exiles: The Story of the American Maroons, New York, NYU Press, 2013.

Nina de Friedemann, Richard Cross, Ma ngombe: Guerreros y ganaderos en Palenque, Bogotá, Carlos Valencia Editores, 1979.

Georg Friederici, Amerikanistisches Wörterbuch und Hilfswörterbuch für den Amerikanisten, Hamburg, Cram, De Gruyter & Co., 1960, p. 191-192.

Flávio dos Santos Gomes, Palmares, São Paulo, Contexto, 2005.

Frances S. Herskovits, Melville Herskovits, Rebel Destiny, New York, London, Whittlesey House, McGraw-Hill Book Co., 1934.

Frances S. Herskovits, “Introduction” in F.S. Herskovits (ed.), The New World Negro, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1966.

Eric Hobsbawm, “Escaped Slaves of the Forest”, New York Review of Books, December 6, 1990, p. 46-48.

Jean Hurault, Africains de Guyane: la vie matérielle et l’art des Noirs Réfugiés de Guyane, La Haye-Paris, Mouton, 1970.

R.K. Kent, “Palmares: An African State in Brazil”, Journal of African History 6, 1965, p. 165-175.

André J.F. Köbben, “Unity and Disunity: Cottica Djuka Society as a Kinship System”, Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, nᵒ 123, 1967, p. 10-52.

Kris Lane, Quito 1599 : City and Colony in Transition, Albuquerque, University of New Mexico Press, 2002.

Joseph C. Miller, Way of Death: Merchant Capitalism and the Angolan Slave Trade, 1730-1830, Madison, University of Wisconsin Press, 1998.

Sidney W. Mintz, Richard Price, The Birth of African‑American Culture, Boston, Beacon Press, 1992 [1973].

Jean Moomou (ed.), Sociétés marronnes des Amériques: mémoires, patrimoines, identités et histoire du XVIIe au XXe siècles, Matoury, Guyane française, Ibis Rouge, 2015.

Joe Pereira, “Maroon Heritage in Mexico” in E.K. Agorsah (ed.), Maroon Heritage: Archaeological, Ethnographic and Historical Perspectives, Kingston, Jamaica, Canoe Press, 1994, p. 94-107.

Richard Price, Maroon Societies: Rebel Slave Communities in the Americas, New York, Doubleday/Anchor, 1973.

Richard Price, First-Time: The Historical Vision of an African American People, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1983.

Richard Price, Alabi’s World, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 1990.

Richard Price, “Scrapping Maroon History: Brazil's Promise, Suriname’s Shame”, New West Indian Guide 72, 1998, p. 233-255.

Richard Price, “On the Miracle of Creolization” in K.A. Yelvington (ed.), Afro-Atlantic Dialogues: Anthropology in the Diaspora, Santa Fe, SAR Press, 2006, p. 113-145.

Richard Price, Travels with Tooy: History, Memory, and the African American Imagination, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2008.

Richard Price, Rainforest Warriors: Human Rights on Trial, Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2011.

Richard Price, “The Maroon Population Explosion: Suriname and Guyane”, New West Indian Guide, nᵒ 87, 2013, p. 323-327.

Richard Price, Sally Price, Les Marrons, Châteauneuf-le-Rouge, Vents d’ailleurs, 2003.

Richard Price, Sally Price, The Root of Roots: Or, How Afro-American Anthropology Got Its Start, Chicago, Prickly Paradigm Press/University of Chicago Press, 2003.

Richard Price, Sally Price, Fesiten, La Roque d'Anthéron, Vents d’ailleurs, 2013.

Richard Price, Sally Price, Saamaka Dreaming, Durham NC, Duke University Press, 2017.

Sally Price, Richard Price, Maroon Arts: Cultural Vitality in the African Diaspora, Boston, Beacon Press, 1999.

João José Reis, Flávio dos Santos Gomes (eds.), Liberdade por um fio: Historia dos quilombos no Brasil, São Paulo, Companhia das Letras, 1996.

Armin Schwegler, Bryan Kirschen, et Graciela Maglia (eds.), Orality, Identity, and Resistance in Palenque (Colombia): An Interdisciplinary Approach, Amsterdam, John Benjamins, 2017.

David Scott, “That Event, This Memory: Notes on the Anthropology of African Diasporas in the New World”, Diaspora, nᵒ 1, 1991, p. 261-284.

H.U.E. Thoden van Velzen, Wim Hoogbergen, Een zwarte vrijstaat in Suriname: De Okaanse samenleving in de 18e eeuw, Leiden, KILTV, 2011.

Michel-Rolph Trouillot, “Culture on the Edges: Creolization in the Plantation Context”, Plantation Society in the Americas, vol. 5, nᵒ 1, 1998, p. 8-28.