Is it a revolution?

“Is it a revolt?” Louis XVI asked on hearing the noise of the crowd. “No, Sire”, came the reply, “it's a revolution”1. The 2018 Italian election followed on the heels of those in Spain, Germany, Austria, the Netherlands, France, Great Britain, and the United States, and in the wake of the Brexit vote. There have been so many rebellions one after the other that they virtually amount to a pacific electoral revolution traversing the Western world. So why not the Italians, after all? Far from being the latest to join this vast revolutionary movement, they are more probably its frontrunners. The Italian insurgency against traditional parties in the early 1990s returned explosively in the 2013 general election, the first since the great financial crisis. This saw the Five Star Movement (Movimento 5 Stelle, henceforth the M5S) – a party born four years earlier by chance, or at least by provocation – beat all comers, winning a quarter of the votes for the Chamber of Deputies.

Knowing who won an election is important. But just as important is understanding what drove many voters to withhold their trust from traditional parties and rebel against them. This electoral revolution is an international phenomenon, analyzed by academics and the press on an international scale. Some observers lay the blame on the electorate, or at least a sizeable segment of it. These voters are said to be unable to adapt to change, hostile to conventional parties, and thus a factor driving the successes of the so-called populist parties that have sprung up to exploit and feed their discontent. For others – who bring to mind, no doubt unwittingly, the lesson of the American political scientist Seymour Martin Lipset to the effect that democratic stability is based on favorable social and economic conditions – it is, rather, politicians and the severe austerity policies they have implemented that are to blame for voter discontent and populist success2. There are also intermediary positions: such as those who argue that right or wrong, policies should largely comply with voters’ wishes. In any case, the outcome of the Italian general election of March 4, 2018 was broadly prefigured by that of the 2013 general election.

In the early 1990s, the political and electoral landscape was profoundly altered by the major investigation into political corruption, known as the “clean hands” operation, and the 1993 electoral reform, in which the proportional system was replaced by a single-ballot regime, with 75% of seats allocated on a first-past-the-post basis and 25% of on a proportional basis. In 1994 the main parties that had governed for nearly half a century throughout the post-war period were swept away and replaced by political parties with few cultural roots and no solid structures. It must be said that over the quarter century since then, the parties have done all they can to confuse voters. Alongside the resounding electoral defeats of certain parties and the appearance of some new faces, there has been a ceaseless round of foundings, refoundings, unifications, splits, and name changes. However strange it may appear – given that his vices largely outweigh his virtues, and he has been beset by scandals since 1994 – for over twenty years now Berlusconi has acted as the pole around which Italian politics gravitates, and whose sway it is unable to shake off. Just as it is unable to move beyond the question of morality in political life, the cause sparking the electoral changes of 1994. This is currently a major issue for all democratic regimes, but Italy is perhaps the only country where it has crystallized in the form of a party like the M5S, currently running high.

Silvio Berlusconi, Forza Italia, 1994.

Italian society has become seriously disenchanted with politics, but this is in large part attributable to extra-political causes. The country's economy has underperformed the EU average since the 1990s. Its GDP has been below the EU average since the early 2000s, and has not yet returned to pre-2009 levels. Amongst EU countries, Italy has the second lowest rate of labor market participation (62% of the population), and one out of four Italians is at risk of poverty. Official statistics indicate very high levels of inequality, steadily increasing since the end of the twentieth century. The income of the richest 1% of the population is 240 times the income of the poorest 20%.

Attilio Pusterla, Alle cucine economiche di Porta Nuova, 1887, Polo Arte Moderna e Contemporanea. Museo del Novecento, Milan.

In parallel to this, Italy's industrial system has been declining for a quarter of a century. Large companies started running into difficulties in the 1980s under the effects of globalization. Some Industrial groups dissolved, and others were bought up by foreign groups. The privatization of major public groups in the 1990s led to the loss of Italy's “crown jewels”, which were often broken up by their new owners3. Industrial districts and SMEs, which in the 1980s and 1990s were extremely dynamic and competitive , are nowadays undergoing large-scale restructuring: some have been dismantled, others have relocated abroad, and those catering predominantly for the domestic market encounter competition from foreign companies.

Gabriele Basilico, Ritratti di fabbriche, 1978-1980, Milan. Fondation Gabriele Basilico, Fondazione Museo di Fotografia Contemporanea (Milan).

The situation in public services is just as depressing. The Italian school and university system is the most underfunded in Europe. Equally, its health system, though considered excellent, is on the decline. The entire public sector is struggling. Public administrations have been left exhausted by New Public Management reforms. After the 2007 financial crisis austerity policies acted as a financial stranglehold on local authorities, while competitive federalism, introduced by the 2001 constitutional local authority reforms, exacerbated competition between southerly and northerly regions.

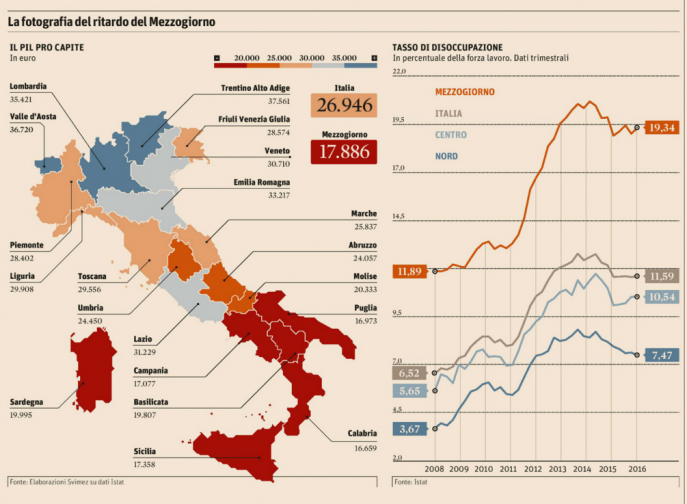

The South (Mezzogiorno) is in a parlous state4. Over the past eight years its GDP has plummeted 13%, twice as much as the rest of the country. According to data produced by SVIMEZ (Associazione per lo Sviluppo dell’Industria nel Mezzogiorno, Association for the Development of Industry in the South), 36% of the southern population is in the poorest quintile of Italians, as against 11% in the Center and the North. In parallel to, this the proportion of the workers beneath the poverty level stands at 24% in the South as against 7% in the Center and the North. One final statistic: the employment rate in the South is 47%, in comparison to 69% in the rest of the country. Southern public services are in a dire situation. To give but two examples: illness drives large-scale health migration from South to North, accompanied by a similar flow of university students, which is unsurprising given the deliberate dismantling of southern universities. One point to be borne in mind is that the political emergence of the Lega Nord (Northern League) in the early 1980s encouraged the demonization of southern society. The South was portrayed as backward, a place where clientelism, corruption, and organized crime were rife. Further, it was said to be responsible for these problems and invited to solve its problems on its own. This interpretation – endorsed from above with the academic authority of Robert Putnam's broadly disseminated research into social capital – was used to justify halting the post-war policy of “extraordinary intervention”, axing public investment, primarily in infrastructure, and above all abandoning the South to mediocre and discredited politicians5. As for the accusation that the South lacked civic mindedness, this is yet to be proven. Although some deny it, a good proportion of southern society is modern, educated, and highly dynamic. But electoral mechanisms and decisions taken by national parties do not favor those sectors of southern society who are critical of dominant political customs – hence do not favor sectors abounding in civic mindedness, preferring instead to hinder and dishearten them as much as possible.

The North-South Inequalities in Contemporary Italy.

It is easy to attribute the current state of Italy to inappropriate government action, the best known (yet not gravest) indication of which is the extremely high level of public debt. The great promise in the wake of changes to electoral law in 1993 was to clean up public finances: in 1994 public debt stood at only 122% of GDP; it is now 130%. Yet center-left parties took modest steps to reduce it when in power from 1996 to 2001 and 2006 to 2008, encouraging privatization, and taking Italy into the Eurozone, albeit with great difficulty and at the cost of yielding certain state prerogatives to the EU. Center-right parties, headed by Berlusconi since 1994, have consistently allowed the level of debt to rise, while Europe has turned a blind eye, before intervening severely at the last moment, as it did in Greece. That is how the Monti government's austerity measures were imposed on a struggling country in 2011.

In October 2011, the president, Giorgio Napolitano (from 2006 to 2015), was harried by EU partners and institutions into dissolving the Berlusconi government. Napolitano imposed an emergency government headed by former EU Commissioner Mario Monti, a liberal-leaning economist. Supported by a parliamentary majority comprising the two main parties – Forza Italia and the Partito democratic (henceforth Democratic Party) – Monti handed out ministerial portfolios to a team of experts, and axed public spending, pushing through a particularly unpopular pension reform. The fate of the Greeks and Spaniards was far worse.

A revolution first launched in 2013

The result of the 2018 elections was prefigured by the 2013 elections, to which the electoral revolution may be traced back. In the 2008 elections, parties from the center-left and left won about 42% of votes cast, parties from the center-right 46%, and those from the center 5%. A center-right government was formed with a comfortable parliamentary majority, headed by Berlusconi. But the joint actions of EU institutions and the Italian president led it to capitulate and accept the Monti government. The next elections were in spring 2013, in accordance with the planned electoral calendar. Abstention rose 5%, the center-left and left suffered a drop of about 10% in their share of the vote, the center-right and right a drop of over 15%, and Mario Monti's centrists took 10% of the vote.

Voters came out, however, in support of the M5S, the party founded by comedian Beppe Grillo. It had met with some success in local elections between 2009 and 2013, but this was the first time it stood in a national election. On its first attempt, it won over a quarter of the votes cast, about 10% more than polls predicted. Studies show that these votes came from both main political alignments, with a clearly larger number of swing voters from the center-left. The same studies also show that younger voters flocked to the M5S6.

However, there was one thing enabling the traditional parties to get around these election results – electoral law. Law no. 270 of December 21, 2005 still governed the general elections of 2006, 2008, and 2013. It had been passed with the backing of center-right parties, despite opposition from the center-left. It had been described by the Northern League minister who tabled it, Roberto Calderoli, as “crap”. Beneath a veneer of proportionality, it stipulated that the winning coalition be guaranteed 340 seats in the Chamber of Deputies. Equally, it introduced a region-by region majority bonus for the Senate. The law thus made different results for the Chamber and the Senate more likely, a risk which transpired in 2013 when the center-left, headed by the Democratic party, won a large majority in the Chamber but none in the Senate. And because governments in the Italian republic have to win a vote of confidence in both chambers, the legislative was condemned to instability. It must also be remembered that on December 4, 2013 the Constitutional Court finally ruled that this law was unconstitutional for two reasons: first, it found that the majority bonus was excessive, and second, it rejected the use of closed lists as stipulated by this law, for this made it impossible for voters to choose among candidates.

Domenica del Corriere, elections at the parliament and the Senate, May, 25th o f1958.

The uncertain electoral verdict did not prevent the Democratic Party from governing for five years. Invoking Italy's obligations to the EU, the Italian president initially encouraged the advent of a government with a Chamber majority but Senate minority (yet able to draw on the support of a few center-right senators). It was headed by the comparatively youthful Enrico Letta, a Democratic Party heavyweight picked by the president in person for fairly transparent reasons, being the nephew of one of Berlusconi's closest and most influential advisers. The majority was shored up when a group of center-right deputies abandoned Berlusconi and switched their support to the government. Meanwhile Bersani, the Democratic Party leader who had run the unsuccessful electoral campaign, resigned. At the 8 December 2013 primaries he was replaced by Matteo Renzi, the mayor of Florence, who soon demanded to be appointed prime minister, once again negotiating the support of deputies from the center-right. Renzi was doubtless a more dynamic prime minister than Letta, but both governments were clearly very weak, pressured by EU bodies, and hostage to the center-right deputies propping up their majority.

Renzi holding Berlusconi on his shoulders, Parody of The Fire in the Borgo by Raphaël (Sirante - street art).

The policies implemented by both Letta and Renzi differed little from the austerity policies of the Monti government. It is only fair to note that Renzi displayed some capacity for innovation, even though his measures departed from the center-left tradition. His government introduced a law on civil partnerships. But more importantly, it loosened up labor law in line with EU and IMF demands, and in the face of open opposition from trade unions. It is hard to gauge whether voters approved of this reform. However, polls showed that voters were fairly dissatisfied with government action on various sensitive issues, including unemployment, pensions, support for the needy, and immigration – not to mention its inaction in the South. As a center-left government, it is unlikely to have endeared itself to the electorate with its support for business and open irritation with trade unions and public – and private-sector employees.

Seeking to capitalize on his popularity in the polls, Renzi immediately set out to consolidate his position by changing the rules of the game. The first occasion was during the EU elections at the height of the crisis hitting Berlusconi (who had just received a criminal conviction and parliamentary ban) and the Northern League, when the Democratic party won 40% of the vote (though with an abstention rate of 42%). After having reached agreement with Berlusconi, Renzi presented sweeping constitutional reforms (which would basically have abolished the so-called “perfect” bicameralism and deprived the Senate of any major role), and sought to get electoral law rewritten. Under the law approved by parliament, a majority of seats would have been granted to any party winning 37% of the vote. If no party reached that threshold, there would be a runoff between the two leading parties. This constitutional reform was rejected by 60% of voters in a referendum on December 5, 2016, partly because in the intervening period Berlusconi had withdrawn his support. Immediately afterwards, and this time with the greatest solicitude, the Constitutional Court ruled that certain articles of Renzi's intended electoral reform were unconstitutional. His initial support had clearly dried up, and the political climate changed. On losing the referendum Renzi resigned and named one of his most faithful lieutenants, Paolo Gentiloni, as prime minister, who carried on with his policies but in far more sober style.

Handover of power between Matteo Renzi and Paolo Gentiloni (décembre 2016).

Source : Wikipedia.

In the meantime, the migration crisis had come to the fore. The number of North African immigrants was never very high, but was amplified by the media and the League’s propaganda7. Matteo Salvini, the successor to the Northern League's long-standing leader Umberto Bossi, renewed the party. First, he changed its name from Norther League to League. Second, he chose to replace the South with immigration as the main polemical subject for his party. Government policy to confront the migrant emergency was visibly timid and contradictory. The Letta and Renzi governments had admittedly pursued a generous sea rescue policy, but they had economized on integration policies, laying themselves open to ferocious criticism from the right and the League, and contributing to the unpopularity of these measures with certain voters. There is no doubt that other EU countries failed to do their part. With the Gentiloni government at the helm, and in the light of poor poll ratings, the new minister of the interior, Marco Minniti, thought it was a good idea to alter tack. The government introduced restrictive new measures, limited the action of NGOs, and signed agreements with the Libyan authorities, sparking criticism from some on the left and Catholic circles.

European migrant crisis provoked a humanitarian crisis in the Southern peninsula harbours as Lampedusa. Since 2014, more than 600,000 migrants arrived in Italy, mostly crossing the Mediterranean Sea. On February 2nd 2017, Italy signed an agreement with the Libyan coastguards: during that year, more than 20,000 migrants were captured and landed in Libya in the midst of a violent context. Italy has been accused to negociate discreetly with Libyan smuggler in order to slow down the arrival of men and women coming from Africa.

The migrant crisis in Italy (Italy navy during a rescue operation).

Immigration was not the only reason for the widespread malaise of center-left voters. It is possible that persistent economic difficulties and the Democratic Party's shift towards the center had a still greater impact. In fact, after its outstanding performance in the 2014 EU elections, the center-left went on to lose virtually all the regional and municipal elections, hit by a swing to the right and to the M5S. Furthermore, Renzi's shift towards the center finally led to the (actually very moderate) left wing splintering away from the Democratic Party, which thus entered the 2018 elections in a seriously weakened position.

One of the most important measures introduced after the formation of the Gentiloni government was a new electoral law, to replace Renzi's proposed law which had been partially rejected by the Constitutional Court. The new law was passed by common assent between the dominant pro-Renzi current of the Democratic Party, Berlusconi's Forza Italia, and the Northern League. Law no. 165 of November 3, 2017 provides for a single round of voting using a mixed system, with 36% of seats awarded on a first-past-the-post basis and 64% on a proportional basis. It favors coalitions and stipulates a minimum threshold of 3% for party representation. The purpose of the law, suspected by some of being unconstitutional once again, was clearly to hamper the M5S, which was topping all the polls. The law's backers hoped to benefit from their strong local roots, which the M5S was deemed to lack, and from the M5S's refusal to enter into a coalition with any other party.

Political outfits, electoral offerings and issues

Let us now turn to the “political enterprises”8 competing on March 4, 2018 and their electoral offerings. The party that most alarmed the others and pundits was the M5S. In the aftermath of the 2013 general election, when it scored 25% of the votes, opinion polls announced a surge in its popularity. After a brief slump during the 2014 EU elections, the M5S rapidly recovered its position in the polls and entered the 2018 elections as the front-runner

If one thing is certain, it is that the M5S is an original political party. In 1994 Berlusconi had founded a major party with Forza Italia. Despite his anti-political pronouncements and style often described as populist, he was one of the best-known businessmen in Italy, the owner of a TV empire, newspapers, publishing houses, a major advertising company, and a supermarket chain. Furthermore, he had close ties with the two major parties that had just collapsed, the Italian Socialist Party and Christian Democracy. The M5S started out as a small outfit, seeking to embarrass other parties, particularly the Democratic Party, rather than aspiring to govern the country. Initially, its ambitions went no further than running a few municipalities9.

The principal characteristic of the M5S was that it chose to criticize traditional political parties and champion morality in public life, while declaring itself a “non-party” with a “non-constitution”. In addition, on being founded the M5S promised “disintermediation”, allowing voter participation via the web. The not very original idea was that if citizens actively contributed to conducting public life, it would become less immoral and more efficient.

Il Blog delle stelle, June 7th of 2018.

A fair share of the M5S's national activity took place on the web. It is important not to underestimate its work to mobilize people, a task mass parties neglected. By polarizing political debate, the M5S reinvented activism and participation, starting with its founder's very popular blog, which tackled such topics as the probity of elected politicians, environmental protection, and the excessive power of big finance. A constellation of meetups – informal and often very active participation forums – was set up across the length and breadth of Italy10. But the M5S devised its policies and selected its candidates mainly in the course of discussions and decisions taken by its members online.

Irrespective of appearances, the M5S is primarily a Zelig party (named after the chameleon protagonist of Woody Allen's 1983 Zelig). This is especially true in terms of its organization. It denies being a “party” but, on closer examination, it turns out to function, when necessary, in an extremely centralized, oligarchic, and authoritarian manner11. Anybody can join, anybody can give their opinion, there are no ideological taboos, but the party leadership is all-powerful. It is embodied by its founder, Beppe Grillo, long accompanied by IT entrepreneur Gianroberto Casaleggio. Together they were the sole owners of the logo. They have always controlled and carefully filtered the movement’s membership, latterly on the Rousseau platform set up and owned by Casaleggio. After Gianroberto Casaleggio died, his role as Grillo's alter ego went as of right to his son Davide. Grillo and the two Casaleggios have always stayed on the sidelines of ballots, but it is also they who, after an online plebiscite, appointed the movement's political leader and prime ministerial candidate. They chose a not particularly competent and clearly inexperienced thirty-year-old Neapolitan deputy named Luigi di Maio. Di Maio was tasked with appointing the leaders and the treasurers of the parliamentary groups both in the Chamber of Deputies and the Senate, with half of the budget of these groups being siphoned off to the Casaleggio company. M5S local and national representatives have to submit to iron discipline, and those who show signs of being unruly are systematically disavowed and excluded, at times after grotesque online denigration rituals. The Zelig party manages to combine the highest and lowest rate of democratic participation.

The M5S is also a Zelig party in terms of its policy program. Admittedly, it makes much of its anti-political tub-thumping style. But it would be wrong to see it as belonging to the populist right. It was born of committed environmentalism, advocates severe controls on the banking system and major financial and industrial groups, and calls for a referendum on the euro. Yet its anti-political diatribes, such as demanding the abolition of MPs' and regional councilors' privileges, are a classic right-wing trope. Over time it has altered its positions on several occasions, in the light of circumstance and interests. As the elections dew near its attitude to the euro and EU institutions became more conciliatory, it watered down its criticism of NATO, and, no doubt to track opinion polls, changed its stance on immigration to a restrictive, securitarian approach closer to that of the populist right. It also changed its mind about tax, SMEs, and unauthorized building. But the economic policies it proposed for the 2018 elections are Keynesian and pro-welfare. The M5S's manifesto promises to halt privatization, relaunch public policies to invest in the South, introduce a “citizens income” for the unemployed, repeal Renzi's labor law (while remaining relatively hostile towards trade unions), re-visit pension reform, encourage sustainable development with “happy degrowth”, and put an end to the pensions of former MPs. Does this make it a centrist party?

The other fundamental feature about its electoral offering is its radical renewal of political personnel, allowing party members themselves to select candidates. The movement's “non-constitution” states that parliamentary candidates must be under forty, have subscribed to the movement's ethical code, have never belonged to secret associations such as the Freemasons, have a clean criminal record, not be under judicial investigation, nor have links of any kind with companies under investigation. Last, none of its parliamentarians may serve more than two terms of office. There seems to be a frenetic search for new people who, however enthusiastic and loyal they may be, are politically inexperienced and lacking in the requisite professional qualifications – virtually none are known in what is commonly called civil society. It is hard to avoid the suspicion that this is an additional means by which Grillo and Casaleggio Jr keep the destiny of the M5S firmly in their hands.

The second main competitor in the 2018 general election was the League. Whereas the M5S is a recent political outfit, the League offers an example of a successful attempt to reposition and restyle a pre-existing party. After the collapse in its support in the 2013 general election, and the scandals involving Umberto Bossi together with his entourage, Matteo Salvini successfully took over the leadership from his supposedly charismatic forerunner. He converted the Northern League, which went from being an ethno-regionalist party calling for the independence of the northern regions, or at least a federalist reform of the Italian state, into a national far-right party. In fact the League presented a joint program with Forza Italia. But in public pronouncements Salvini confirmed that the party belonged to the populist right, insisting on five main components: racist and identity exhortations asserting Italians were “masters in our own home” (a theme used to build links with the Front National in France and national leaders of the Visegrad group); hostility to the euro, EU institutions, and the EU fiscal compact; aversion to civil unions; re-establishing security, including by changing laws governing legitimate defense; and finally, turning back “economic” migrants and deporting illegal migrants. In the joint program with Berlusconi he particularly emphasized the promise to lower taxes, with an 18% flat-rate income tax, and to simplify public administration.

Screenshot of Matteo Salvini's twitter wall.

Yet removing the reference to the North from its logo did not suffice to erase its past. Making the main enemy immigrants, as opposed to the South, did not suffice either, as its electoral results proved. Be that as may, Salvini made up for these shortcomings with his strategy for recruiting candidates. In the South, candidates were carefully selected from among survivors of Berlusconism and on occasions of Christian Democracy, and mainly from among former post-fascists. In the Center and North, on the other hand, Salvini favored candidates who held local office for the party, such as mayors, assessors, and municipal and regional councilors.

The third political party fighting the election was Berlusconi's Forza Italia, part of the European People's Party. Despite his parliamentary ban for a tax fraud conviction, Berlusconi led his party's campaign and placed his name on its logo. Given that he is now over eighty, one could legitimately have expected him to designate his successor. From the outset the party exerted less pull than previously, but Berlusconi still put up a stiff fight against Salvini for leadership of the center-right. Given Italian electoral law, and despite official denials, the prospect of agreeing to govern with Renzi's Democratic Party clearly figured among its plans, an agreement that EU partners looked upon most favorably. Thus after having dusted off his anti-political discourse and populist style, Berlusconi presented himself as speaking for the European People's Party, and providing a bulwark against the M5S's supposed populism, and an antidote to the populism of his ally Salvini. His campaign focused on an overhaul of the tax system and introduction of a flat tax. It also committed to overturning the pension reform passed under the Monti government, with a proposed minimum pension of €1000. The final aspect related to immigration, with the promise to curb the flow of immigrants and send back at least half a million of them.

Let us now turn to the Democratic Party, established in 2007 when some heirs to the Communist Party fused with some of their Christian Democracy counterparts. The Democratic Party immediately adopted Blairite language and policies. After the calamitous 2008 general election, Pierluigi Bersani sought to change tack, though he subsequently supported without opposition the Monti government's austerity measures imposed between autumn 2011 and spring 2013. When Bersani was compelled to resign after disappointing election results, Renzi took the party reins. Renzi was foreign to both the main Democratic Party's political traditions. His plan was to reposition the party on the center ground, and to seize the opportunity presented by the imminent end to Berlusconism. This worked for the 2014 EU elections, when Berlusconi was at his weakest, but was then belied by successive ballots. At local elections, the Democratic Party lost control of various cities including Rome, Turin, Genoa, and Venice, and its constitutional reform program was rejected in the 2016 referendum. In the wake of the modest achievement of the Renzi and then Gentiloni governments, certain serious bank scandals involving figures in Renzi's entourage, and the split of the party's left flank, it entered the campaign severely damaged, with a manifesto of strict adherence to EU policy. Furthermore, Renzi prioritized personal loyalty in his selection of candidates, often appointing virtual unknowns for first-past-the-post constituencies. The obvious yet officially denied prospect of an agreement with Berlusconi, which was certainly not popular among his traditional electorate, also needs to be included in the picture.

The other parties fighting the election may be mentioned for sake of completeness. On the left were: Emma Bonino's party with a radical pro-European manifesto, and coalition ally with the Democratic party; the breakaway former Democratic Party members grouped under the banner Liberi & Uguali (Free & Equal, L&U), offering a classic program of welfare and state intervention; and a radical left-wing party named Potere al popolo (Power to the people). On the right were: Fratelli d’Italia (Brothers of Italy, “Fratelli d’Italia” being the first words of the national anthem), comprising a few former neo-fascists mainly from the Movimento Sociale Italiano (Italian Social Movement) and coalition partners of Forza Italia and the League; and two openly fascist parties, Forza nuova (New Force), and Casa Pound (named after the 20th-century US poet who supported Mussolini's fascism).

The different parties competing at the March elections of 2018.

To close this section on the electoral offerings of the parties, additional information may be gleaned by looking at the social profiles of elected candidates. Though it needs treating with requisite caution, parliamentary semi-official data provides some interesting insights. The M5S parliamentary group comprises 13% barristers (traditionally a profession producing many MPs), 11% employees, 17% self-designated entrepreneurs, 7% teachers, 7% doctors, together with a solitary MP from a blue-collar background. The rest come from varied professions as consultants, business leaders, experts, journalists, in the military, and so on. The Democratic Party's group comprises 14% barristers, a remarkable 13% party officials, 9% self-designated business leaders, 9% academics, 9% employees, 7% journalists, and 4% entrepreneurs. Teaching, with a traditionally large share of center-left MPs, accounts for a mere 4%. The profile of Forza Italia MPs conforms to expectations with 21% entrepreneurs, 15% barristers, 9% business leaders, 6% journalists, 6% academics, plus one doctor and two employees. As for the League, 10% of its MPs give local elected official as their profession, a category not found for the other parties, together with 12% barristers, 13% entrepreneurs, 13% employees yet again, and 3% journalists. Overall, three-quarters of M5S MPs hold university diplomas (up to the level of doctorate), as do two thirds of Democratic Party and Forza Italia MPs, and 60% of League MPs. Equally, 45% of M5S MPs are women, and 75% percent are under forty. For the Democratic Party, Forza Italia, and the Northern League, about a third of MPs are women, and the proportion of MPs under forty stands respectively at 20%, 10%, and 40%. From this perspective it is hard to deny that the politicians of the four main rivals present fairly different social profiles, aligned with their target voters.

The main topic of the election campaign was how to contain the M5S, accused of populism. The Democratic Party and Forza Italia openly campaigned against it, with the support of major national newspapers and leading TV channels (some belonging to Berlusconi), the two parties thereby indirectly confirming their intention of entering into an agreement after the elections. The other main topic was the struggle to succeed Berlusconi himself, the undisputed protagonist of Italian politics over the past quarter century. On the one hand, Salvini openly ran as the center-right candidate. On the other, with Berlusconi – the great enemy who had hitherto compelled the left to unite – now in decline (a factor which goes some way to explaining the breakaway by Liberi & Ugual), and the center-left slipping behind, Renzi also positioned himself as a leader, shifting towards the center ground in a redrawn political and electoral landscape. He confirmed his intentions by emphatically displaying his agreement with Macron. Berlusconi, it must be said, fought tooth and nail to hamper the plans of both Salvini and Renzi.

The voters' verdict

How did voters react? The first overall point to make is that abstention rose by 2%, with 73% of those registered casting a vote as against 75% in 2013. Despite appearances, this is not a bad result, quite the contrary in fact. In 2013 polling stations were open on the Sunday and on the Monday morning. In 2018 they were only open on Sunday, March 4. The election campaign was also very poor, due to a reform that abolished the reimbursement of campaign expenses and ended public funding for political parties. Thus overall, and despite poll predictions, the level of participation remained stable. Nevertheless, a few differences between the North and the South may be observed. There was a slight drop in the North, while in southern regions, with a traditionally lower turnout, the proportion of people voting actually increased on 201312.

All in all, the center-right coalition won about 12.2 million votes, 2 million more than in 2013 – bearing in mind that in 2013 a centrist party headed by Mario Monti had considerably weakened the center-right, winning 3.5 million votes. The big winner was the League, quadrupling its score to win 5.7 million votes, to the detriment of Forza Italia. On the center-left, the Democratic Party won 7.5 million votes, to which may be added the 1.1 million votes for the breakaway Liberi & Uguali. Their combined total is far from the 10 million votes won by Bersani five years previously, and still further from the record 14 million votes the Democratic Party garnered in 2008. With 10.75 million votes, the M5S was up 2 million on the previous ballot, making unprecedented gains for an established party and confirming its place as the leading party. To finish, the radical left (Potere al popolo) scored 300,000 votes, and the two openly fascist parties (Casa Pound and Italia agli Italiani-Forza Nuova) a little over 400,000 votes.

Data on swing voters by two major polling institutes, SWG and IPSOS, sheds light on voters' choices13. According to IPSOS, 76% of M5S voters had already voted for it in 2013. According to SWG, this figure was 58%, with 10% having previously supported the Democratic Party (in the 2014 EU elections), 20% having abstained in 2013, and 6% having voted for Forza Italia or Monti's party. IPSOS data is broadly similar, with the M5S picking up 14% of former left-wing voters and 8% of former Forza Italia voters. One third of Forza Italia voters switched to the League, according to IPSOS, and one quarter according to SWG. Still according to SWG, about 8% of League voters came from the M5S, a figure IPSOS puts at 6%. Both institutes agree that few voters swung from the left to Forza Italia or the League. According to IPSOS, 30% of those who had voted for Monti in 2013 switched their allegiance to Forza Italia, 30% to the Democratic Party, 10% to the right-wing Fratelli d’Italia, and 8% to the League. As for the Democratic Party, it held onto 43% of its 2013 voters, with 14% swinging to the M5S and 22% choosing to abstain. One final, worrying data from the IPSOS poll is that 35% of young voters abstained. The outcome was similar for the subsequent regional elections in Molise and Friuli-Venezia Giulia and for the municipal elections held last June.

The IPSOS poll also provides information about voters' social profiles14. The Democratic Party was most successful with the elderly and retired. Bonino's party, a coalition ally of the Democratic Party, did best among degree holders, students, and middle- and upper-income groups, siphoning off votes from its coalition partner. The League did particularly well with the self-employed, blue-collar workers, and homemakers. Apparently the M5S is now the party that most fully represents Italian society, though it needs noting that it is the most popular party among degree holders, scoring 29.3%, ahead of the Democratic Party, traditionally considered as the preferred option of the educated classes, with 21.8%. The M5S was also the choice of 36.1% of voters with a school-leaving diploma (as against 16.1% for the Democratic Party). The M5S attracted 31.2% of business leaders and entrepreneurs, 31.8% of the self-employed, 36.1% of employees and teachers, 37% of blue-collar workers, and 37.2% of students and the unemployed. Further, it was the leading party across all professional categories bar pensioners (among whom it came second to the Democratic Party). It even beat the League and Forza Italia among entrepreneurs and business leaders. Equally, it was the most popular party among public-sector employees, who hitherto lent towards the center-left. Lastly, Liberi & Uguali did best among social groups deserting the Democratic Party, that is to say the middle classes, students, and degree holders.

It is not surprising, despite suggestions to the contrary, that the League did extremely well with the working classes. The first point is that electoral data does not show any significant flow from left-wing parties, so working-class voters who supported the League are probably those who used to vote for Forza Italia, and for Christian Democracy before that. The rump of Democratic Party supporters is less socially homogenous. On the one hand, data on urban voting chimes with that for many left-wing parties in Europe, making it the party of the educated middle classes, wealthy cosmopolitans, social groups with an interest in LGBT rights and living wills, and those who tend to view migrants generously15. On the other hand, the Democratic Party retained its working-class roots thanks to older voters who remained faithful to the left-wing tradition. A survey conducted by the CGIL (Confederazione Generale Italiana del Lavoro, Italian General Confederation of Labor) – a union that is traditionally close to the Communist and Socialist Parties and that came in for rough treatment by Renzi – shows that of its 5 million members (half retired) 35% voted for the Democratic Party, 33% for the M5S, 10% for the Northern League, and 11% for Liberi & Uguali16. In the perception of this specific group of voters, the M5S seems to occupy a space which, if not on the left, is at least contiguous to it.

The South, Center, and North.

The Gentiloni government and the Democratic Party sought to persuade people that the financial and economic crisis was now a thing of the past. But a large proportion of voters disagreed, as indicated by the electoral map. The most significant difference in voting patterns, apart from that between cities (which are left-leaning, especially city centers) and the suburbs and provinces, was between the major zones of the South, Center, and North. In the South, the M5S's electoral offering went down a storm, while in the Center and the North, the League made serious headway. Let us now look in greater detail at the results for each of these geographical zones, starting with the South17.

Mapping the 2018 Election.

In the 2013 elections the M5S had already won over 25% of the votes in this part of the country, broadly in line with its results nationwide. In 2018, while making moderate progress in the Center and the North, it leapfrogged to over 40% in the South. As for the center-right, it equaled and even slightly bettered its 2013 score in the South, while the Democratic Party, together with Liberi & Uguali, took a hammering, which may be readily explained by the inadequacy of their action in parliament and in government.

From the outset it was clear that the South was a major prize. In a swathe running from Rome to the South, and taking in Sardinia and Sicily, the M5S came first in terms of votes and parliamentary seats. In Latium, it took 35% of the vote (up 10% on 2013), in Abruzzo 40%, and in the seven other southerly regions 47% (15% above its national score), scooping 60% of parliamentary seats. Of course, on closer examination the situation is more complex in the southerly constituencies and regions. In the northerly provinces of Calabria, for example, the M5S reached 50%, while in its southerly provinces it topped out at 37%18. But that does not alter the overall picture.

In comparison to past results, and despite a slight increase on 2013, center-right parties performed disappointingly. The 30% they received in this part of Italy was seven points below their national score. This was all the poorer bearing in mind that the UDC (Unione dei democratici cristiani e di centro, Union of Christian and Center Democrats), with a strong regional presence, and which had backed Monti's party in 2013, aligned itself with the center-right this time round. But the dynamism provided by the League in the Center and North was lacking. While the million votes and 23 seats won by the League are not irrelevant, the figures are way below those for the Center and North. The League's vote share hovered mainly around 5%-6%, reaching 10% only in Latium and Molise. Still, its xenophobic stance chimed with certain voters, and its share rose to 10%-15% in some regions with large-scale seasonal immigration (for orange-picking for example) where immigrants have rebelled against their extremely undignified living conditions19.

Despite holding power in nearly all the southern regions, the Democratic Party and its allies did catastrophically. Even combined, they did not top 16%, down more than 7% on 2013. Mirroring its results throughout the country, the Democratic Party did a bit better in middle-class districts of cities such as Naples, Palermo, and Rome, but poorly in working-class districts20. Particularly qualified candidates were, however, a relative exception, with Paolo Siani in Naples being an exemplary case. Although a doctor and brother of a journalist assassinated by the Camorra in 1985, he came second, behind the M5S candidate. It is certain that the Democratic Party cannot blame the breakaway Liberi & Uguali for its woes, given that the latter did well where the Democratic Party was strong, and struggled where the Democratic Party did too. Voters – broadly similar for both parties, being educated, middle- and upper-income city-dwellers – clearly saw the breakaway movement not as an alternative but as an (albeit distinct) sister formation.

Interpreting what voters choose and want is, as is well known, vital to political combat. What interpretations were put forward for these differences at the ballot box? One explanation eagerly taken up by major national newspapers and amongst the losing Democratic Party and center-right was that, in the South, the M5S's proposed “citizen's income” was decisive. It was said to offer yet further confirmation of an indelible cultural trait of southern society, namely its propensity to depend on welfare doled out by politicians and the state. Citizen's income is a welfare measure, debated throughout Europe, and no doubt very popular, whereas the vote for the M5S was in fact an open rebellion against clientelism.

The M5S has a large number of energetic activists, though with little in the way of local roots. Personal relationships traditionally count for much in the South, but not for the M5S. Its political staff are young people recruited among the many degree or school-leaving diploma holders with no political background or notable experience in local government (the municipalities run by the M5S being largely concentrated in the Center and North). The M5S vote primarily represents a vast subversive movement by a portion of Italian society neglected for decades, and abandoned to government policies that have become ineffective, particularly in a period of severe budget cuts.

Several newspaper reports confirm this latter reading, of which two will suffice here. Pomigliano d’Arco is a town of 40,000 inhabitants in the vicinity of Naples. Extraordinary intervention policies had sited a large Fiat factory there, employing around 7000 people, without counting the many indirect jobs. Over recent years Fiat restructured the factory, laying off a share of the workers and ruthlessly marginalizing the trade unions. In 2015 Fiat CEO Marchionne met with Prime Minister Renzi, who publicly gave greater credit to Marchionne than to the unions for protecting jobs. In Pomigliano the M5S won 64% of the vote, as against the Democratic Party and Forza Italia, both on 11%. Ten years earlier, the center-left had scored 40%, and still retained 33% in 201321.

Correlation bewteen industrial areas and electoral results: the napolitan example.

Left: The Alfa Romeo Pomigliano d'Arco plant.

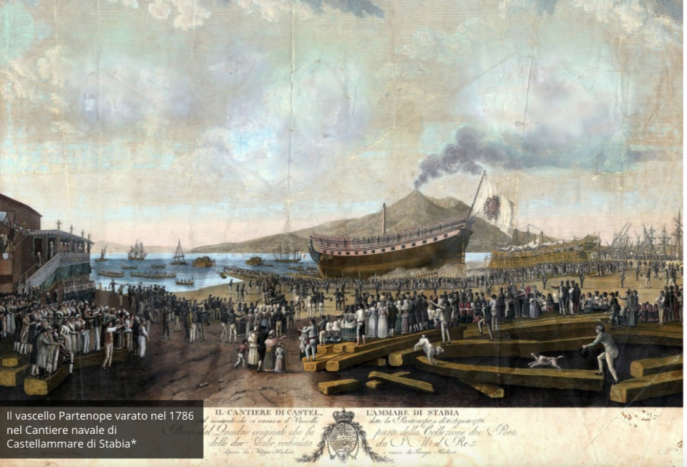

Right: Shipyard of Castellamamare di Stabia, created in 1783.

A few miles away lies Castellammare di Stabia, a town of 60,000 inhabitants and headquarters to a shipbuilder that has flourished there since the late eighteenth century. The M5S won 46% here, the center-left 15%, Forza Italia 22%, and the League nearly 4%. The shipyard has been in a critical situation for years. Fincantieri, which has just linked up with the French group STX, has long been diverting production towards other dockyards, particularly in the North. As a union official interviewed by the journalist observed:

Votes for the M5S were a rebellion… In Castellammare and Torre Annunziata the poverty is palpable. The parents are in prison and their children go about the streets armed. The center-left has turned its back on workers. The Democratic Party region of President Vincenzo De Luca uses EU funding to finance public works, which are a goldmine for the companies running the tenders but translate into miserly wages of €400 or €500 a month for those working on them22.

The vote in central Italy was also a subversive movement in a region once known as the “red zone”, with Florence and Bologna as its capitals, run by the Communist Party for an unbroken fifty years. The political cohesion of the area had been disrupted for quite some time. The Communist Party first recycled itself as the Partito democratico della sinistra (PDS, Democratic Party of the Left), then as the Democratici di sinistra (Democrats of the Left), before merging with former members of the now defunct Christian Democracy. This paved the way to the formation of the Democratic Party, which within a quarter of a century nevertheless managed to unpick the close ties the Communist Party used to have with its electorate. Over the past decade the Democratic Party has lost major municipalities one after the other, generally to the M5S (but at the municipal elections of last June to the League as well). In the 2013 elections MS5 chalked up scores in the 25%-30% range, before picking up an additional 3%-4% at the latest elections.

The most surprising data is nevertheless the advances made by the League, snatching two thirds of the electorate from Berlusconi's Forza Italia. In fact right-wing voters have become more radical. A part of the country Putnam saw as enjoying particularly high levels of social capital, together with a deep-rooted tradition of civic culture, has just enthusiastically embraced the xenophobic and securitarian political offering of Salvini's League. The hardest hit by this shift has been the Democratic Party, which, on 25%, finds itself beaten into third place in many constituencies. So what happened in this part of Italy?

Two hypotheses may be put forward23. The first sees economic transformations as the cause. The local economy of the red zone, based on SMEs who were already struggling in the face of international competition, was hard hit by the economic crisis24. The employment rate dropped far more in central Italy than it did in northerly regions (down 1.4% as against 0.4%). In Le Marche, where the M5S and League were most successful, there was an even greater drop than in the South (down 2.6% as against 2.5%). The youth unemployment rate rose even more than elsewhere (up 18.5% as against 16.6% nationwide), while the 3.9% drop in per capita GDP during the initial years of the crisis (between 2007 and 2012) was far greater than in the North (down 1.2%) and the South (down 1.7%). In the zones with the lowest employment rate the Democratic Party shed even more votes than in high-income zones and in those with higher rates of employment.

Casa del popolo di Grassine (Bagno a Ripoli), années soixante.

The second hypothesis focuses on political and cultural factors. In these regions the end of the Communist Party signaled the disappearance of a key body of representation, government, social protection, and civic education. In power, the communists (with their socialist partners) always had a reputation for high-quality governance, attentive to local society's requirements, economic development, and public service needs. At the same time the party acted as a vast network of associations, epitomized by the “People's Houses”25. When the party disappeared in 1989, its successors abandoned its techniques for building up and retaining its electorate. The mass parties of yesteryear have disappeared throughout Europe, and current opinion argues that this disappearance was inevitable. Social and economic changes, social differentiation, new forms of political communication, and rejection by younger generations are pointed to as reasons driving this. In fact the M5S and the League show that activism and civic involvement are far from having dried up. Be that as it may, an original and no doubt exceptional set of government and collective measures has disappeared in the regions of central Italy. Consequently the unique form of civic mindedness, cultivated by the Communist Party and admired by Putnam, has disintegrated. And the social cohesion built up by the party and the authorities in communist-run regions, provinces, and town halls, linking the middle classes, the self-employed, and small and medium-sized business owners, has crumbled with it.

Let us turn last to the regions of the North, the most industrialized part of the country. Like the South, the North is a politically and socially heterogeneous. Until the late twentieth century the political and electoral map was split into two, with a “white zone” to the east (Triveneto and a few adjacent Lombard provinces) dominated by Christian Democracy, and an “industrial triangle” to the west (Piedmont, Liguria, and much of Lombardy) that was politically more volatile. This situation became increasingly blurred, for at least three reasons. The first was the decline of major industry in the west and the fanning out of SMEs across Triveneto which, after Milan, is now the most economically dynamic part of the North. The second is the disappearance of the great Catholic party (Christian Democracy). The third relates to regional governments. For years, Veneto and Lombardy have been run by the center-right, and for the past ten years at least have been presided by members of the League. This helps explain why the League picked up so many additional votes in the March 4, 2018 general election, reaching 30% and crowding out Forza Italia. In Piedmont and Liguria, on the other hand, though the League increased its vote share, it ran 10% below its average elsewhere in the North.

As for the M5S, it was already attracting a quarter of votes in 2013, in both the east and west. This time it added an additional 4% in Lombardy. However prosperous the North may be, there is a widespread feeling of discontent, particularly among the younger generations, in addition to disappointment with left-wing parties. An example is the province of Turin, in Piedmont, where the Democratic Party backed the construction of a major rail tunnel to France against local wishes, whereas the M5S supported local opposition to the tunnel.

The Democratic Party and the center-left are on the decline everywhere (as is Forza Italia). It managed to retain its seats only in certain urban constituencies in Milan, Turin, and Venice, thus confirming it is the party of the wealthy and the educated. In Turin, in the city-center constituencies, the Democratic Party won 40% of the vote, and even the left-wing breakaway party notched up one of its best results. On the other hand, a significant share of its electorate in the suburbs and working-class districts appears definitively won over to the M5S. Turin is an interesting case, especially because two years ago the Democratic Party mayor was replaced by a M5S mayor, who has been targeted in the local press by an unrelenting campaign of harsh criticism accusing him of mediocrity and inefficiency.

If the outcome of the elections confirmed the position of the M5S, the new factor was the score of League, really very high in the east but sizeable in the west too. The most straightforward interpretation attributes this to its xenophobic stance and the personal decline of Berlusconi. But there is no shortage of more complex explanations. In Lombardy and Veneto, not only do two regional presidents come from the League, but there are also many mayors and local politicians from its ranks who enjoy a relatively good reputation. This means that the League can draw on a dense organizational apparatus with multiple branches. It has also actively nurtured a network of energetic activists, unlike the Democratic Party or Forza Italia. When Christian Democracy disappeared, which had relied on a network of parishes and Catholic associations, the League stepped in to replace it, presenting itself as a party of reliable government with roots in local society, whose interests it heeded and protected. Equally, the decline of the Catholic Church's social presence led to the eclipse of a number of inhibitors. On the whole parishes have resisted, and there are still active Catholic volunteer networks, especially those working to help migrants. But Pope Francis's calls for solidarity have resonated little with the population. This shows, once again, that political cultures are not a legacy of the past, but depend largely on the institutions working to shape and safeguard them.

As for the League, it has turned its back on the secessionism of its early days, no longer dreaming of a Padania (the regions along the Po Valley) as a separate nation from the rest of Italy, instead lending recent backing to a highly combative autonomist movement. Two (consultative) referendums have been held, one in Lombardy and the other in Veneto, calling for greater autonomy from the state, which is blamed not so much for the difficult conditions facing the country, but, as ever, for the slowness, inefficiency, and various forms of wastage imputed to public bodies. Closer examination shows that the League represents an ambivalent feeling of discontent. As in its early days, this discontent is that of the periphery towards rich regions. In the North there are certain very fragile segments of society, as indicated by the sizeable increase in the number of those at risk of poverty, rising from 8.3% in 2006 to 15% in 201626. All in all, upward social mobility in the North has stalled in comparison to 5 years ago. This is the case for 67% of the population, with 30% moving downwards even27. The League also manages to represent the discontent of more dynamic sectors in the business world, the very ones that reacted to the great financial crisis by restructuring to face competition on international markets. For these sectors, the League's demands for greater autonomy and substantial cuts in taxation are more than welcome.

For the time being the League's xenophobia is incidental. It is possible that a fair share of the small business owners, professionals, and blue-collar workers who vote for the League are afraid of and hence reject migrants. Nevertheless, while this phenomenon should not be underestimated, it should not be overestimated either. There are two reasons for this. First, displays of intolerance have thus far been fairly episodic. Second, there has been no consistent transfer of left-wing voters to the League, not even among the most disadvantaged, for whom such issues as security, unfair competition from immigrants, and the privileges bestowed on them by government authorities could be expected to carry the day. Data suggests there is virtually no voter flow from the Democratic Party to the League. Xenophobia is no doubt a threat. But it is a threat whose causes need to be sought in the economic and social conditions on which the League has grafted its political offering, based on xenophobia, identity politics, and sovereignty, but also on denouncing government inability to negotiate more effective EU aid to tackle immigration issues and rein in austerity policies. If this interpretation is correct, renewed confirmation of EU-imposed austerity policies only risks stirring up feelings of xenophobia – a danger that needs to be taken seriously into account.

Conclusion

Italian voters have reshuffled the electoral map, but it is far from stable. After a revolution, the return to order is never smooth. The Democratic Party and Forza Italia, anticipating their defeat, had sought to turn things around by brandishing the false specter of a populist threat, and proposing an umpteenth electoral reform. Had the electorate voted as they hoped, this would have resulted in a union sacrée of neoliberal, pro-EU, anti-populist parties, as in France and Germany. Italy would have stepped back in line. Had the two parties longer memories, they would have remembered that electoral law in Italy has never delivered the expectations of those who draw it up in their favor. The eighty-seven-day lapse before a new government was formed, thanks to an agreement between the M5S and the League (curiously described as a “contract” rather than a coalition), shows that this time round the law generated a gouvernement that was all but introuvable. The complexity of the situation also stems from the fact that, after twenty-five years of left-right competition governed by majoritarian representation, the competing parties have forgotten the rules of proportional representation, in accordance with which parliamentary majorities are formed in the aftermath of elections.

No doubt the M5S has pulled off an extraordinary victory. However, it remains fragile, first of all due to its inexperienced leadership, which has made criticizing other parties its fundamental raison d’être. Given the results, the most likely prospect was an agreement with the Democratic Party, to which the M5S is close in terms of its voters' social profile and the interests it defends. But the Democratic Party, disappointed by its unanimously announced defeat, has consistently refused to listen to proposals by the M5S, falling back on denouncing the populist threat. That is how the party led by Di Maio was pushed into the arms of the League, the only point in common between the two parties being their criticism of conventional politics.

Salvini, Di Maio et Berlusconi endodying the “The Cardsharps” by Caravage (street art - Sirante).

For its part, the League seems to have pulled off the challenge of radicalizing moderate and conservative voters, plus the hitherto unimaginable one of providing an alternative the leadership of Berlusconi. But it remains a northern party, and it is to be seen whether its xenophobic statements, and government action with the M5S, will enable it to make serious inroads outside its northern stronghold in the future, and definitively relegate Berlusconi's leadership to the past.

The future is unpredictable. But looking at the program of the cabinet finally put together by the M5S and the League – headed by law academic and political novice Giuseppe Conte – seeking to reconcile the two parties' highly contradictory manifestoes, it is especially hard to detect the conditions that could deliver stability. Nor is there any indication that the electorate's discontent is about to subside. What is certain is that events in Italy on March 4, 2018 represent a new if confused chapter in the great electoral revolution that has recently shaken western democracies. Although intriguing for observers, it is an uncomfortable movement for politicians, and an extremely worrying one for citizens.

Notes

1

I wish to thank Cecilia Biancalana and Domenico Fruncillo for their help and advice.

2

Seymour Martin Lipset, Political Man. The Social Bases of Politics, Doubleday, New York, 1960.

3

Giuseppe Berta, Che fine ha fatto il capitalismo italiano? Bologna, Il Mulino, 2017.

4

Carlo Trigilia, Gianfranco Viesti, La Crisi del Mezzogiorno e gli effetti perversi delle politiche, Il Mulino, n° 1, 2016, p. 52-61.

5

Robert D. Putnam, R. Leonardi, R. Y. Nanetti, Making Democracy Work : Civic Traditions in Modern Italy, Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1993.

6

Lorenzo De Sio, Matteo Cataldi, Federico De Lucia (dir.), “Le Elezioni politiche del 2013”, Centro Italiano Studi Elettorali, 2013.

7

In 2015, Italians thought that over 25% of people in Italy were foreigners. In fact the proportion was stable, at 8% Il Post, Monday, March 27, 2017.

8

Michel Offerlé, Les Partis politiques, Paris, Presses Universitaires de France, coll. Que sais-je?, 2002.

9

Those wishing to learn more about this original party may consult Piergiogio Corbetta (ed.), M5s. Come cambia il partito di Grillo, Bologna, Il Mulino, 2017; and Paolo Ceri, Francesca Veltri, Il movimento nella rete. Storia e struttura del Movimento 5 Stelle, Torino, Rosenberg & Sellier, 2018.

10

For example: Cecilia Biancalana, “Dalla protesta al potere: il Movimento 5 stelle a Torino”, Polis, Ricerche e studi su società e politica in Italia, no 3, 2017, p. 329-356.

11

Though not in fact more than its rivals. Berlusconi is the absolute master of Forza Italia, Salvini the undisputed leader of the League, and Renzi stifled all debate in the Democratic Party. Yet none of these claims to be a paragon of democracy.

12

On this subject and on how to interpret the results more generally, see Barbara Bertoncin, Frattura di classe. Intervista a P. Feltrin, Una città, n° 247, March 2018. An overall framework is provided in Matteo Cavallaro, Giovanni Diamanti, Lorenzo Pregliasco, Una nuova Italia. Dalla comunicazione ai risultati, un'analisi delle elezioni del 4 marzo, Roma, Castelvecchi, 2018.

13

Termometro politico, March 6, 2018; IPSOS report on the March 2018 Italian elections.

14

TGCOM, March 5, 2018. See too Davide Mancino, Il voto ai partiti, il lavoro e il titolo di studio: esiste una correlazione? Il Sole/24 hore, March 14, 2018.

15

Andrea Maccagno, “Zone rosse: il centro sinistra si rinchiude nei centri urbani”, Youtrend. Alberto Magnani, “Così vicine, così lontane. Perché città e province votano in maniera opposta”, Il Sole/24 ore, March 6, 2018.

16

Termometropolitico, April 24, 2018.

17

Domenico Fruncillo, “Il voto al Sud, e quei pregiudizi da smontare”, Sbilanciamoci info, March 21, 2018. See too Marta Fana, Giacomo Gabbutti, “I numeri per capire il voto al sud”, Internazionale, March 23, 2018. Gianfranco Viesti, “Il divorzio tra il sud e il centrosinistra”, Il Mulino, April 23, 2018.

18

Vittorio Mete, “Calabria a 5 Stelle”, Il Mulino, April 16, 2018.

19

Claudio Dionesalvi, Silvio Messinetti, “Salvini torna a Rosarno. Sul carroccio del vincitore”, Il Manifesto, March 29, 2018.

20

On Naples, see Adriana Pollice, “Barra e Scampia, il miracolo 5 Stelle parte dalle periferie”, Il Manifesto, March 22, 2018. On Rome, see Federico Tomassi, “Il voto a Roma alle elezioni politiche e regionali del 2018”, March 29, 2018.

21

Adriana Pollice, “Pomigliano, il ciclone Di Maio sulle ceneri della Fiat”, Il Manifesto, March 22, 2018.

22

Adriana Pollice, “Castellammare. Il cantiere langue e la povertà dilaga, ma il centrosinistra non se n’è accorto”, Il Manifesto, March 22, 2018.

23

These hypotheses are put forward by Francesco Ramella in “Il voto nelle (ex) regioni rosse dell’Italia del mezzo”, Il Mulino, March 14, 2018.

24

Luca Orlando, “Da Sassuolo a Lecco, i distretti con la Lega. Bassi salari e lavoro la leva dei 5 Stelle al Sud”, Il Sole/24 ore, March 7, 2018.

25

Mario Caciagli, Addio alla provincia rossa. Origini, apogeo e declino di una cultura politica, Rome, Carocci, 2017.

26

Luca Orlando, “Da Sassuolo a Lecco, i distretti con la Lega. Bassi salari e lavoro la leva dei 5 Stelle al Sud”, Il Sole/24 ore, March 7, 2018. See too Daniele Marini, “Il Nord a due velocità è arrabbiato con la politica”, La Stampa, March 14, 2018.

27

Dario Di Vico, “Ecco chi ha votato Salvini. Non solo i dimenticati. Anche i vincenti della globalizzazione hanno scelto la Lega”, Corriere della Sera, March 18, 2018.

Bibliographie

Giuseppe Berta, Che fine ha fatto il capitalismo italiano?, Bologna, Il Mulino, 2017.

Barbara Bertoncin, Frattura di classe. Intervista a P. Feltrin, Una città, n° 247, mars 2018.

Cecilia Biancalana, “Dalla protesta al potere: il Movimento 5 stelle a Torino”, Polis, Ricerche e studi su società e politica in Italia, n° 3, 2017, p. 329-356.

Mario Caciagli, Addio alla provincia rossa. Origini, apogeo e declino di una cultura politica, Roma, Carocci, 2017.

Matteo Cavallaro, Giovanni Diamanti, Lorenzo Pregliasco, Una nuova Italia. Dalla comunicazione ai risultati, un'analisi delle elezioni del 4 marzo, Rome, Castelvecchi, 2018.

Paolo Ceri, Francesca Veltri, Il movimento nella rete. Storia e struttura del Movimento 5 Stelle, Turin, Rosenberg & Sellier, 2018.

Piergiorgio Corbetta (dir.), M5s. Come cambia il partito di Grillo, Bologne, Il Mulino, 2017.

Claudio Dionesalvi, Silvio Messinetti, “Salvini torna a Rosarno. Sul carroccio del vincitore”, Il Manifesto, 29 mars 2018.

Marta Fana, Giacomo Gabbutti, “I numeri per capire il voto al sud”, Internazionale, 23 mars 2018.

Domenico Fruncillo, “Il voto al Sud, e quei pregiudizi da smontare”, Sbilanciamoci info, 21 mars 2018.

Andrea Maccagno, “Zone rosse: il centro sinistra si rinchiude nei centri urbani”, Youtrend, mars 2018.

Alberto Magnani, “Così vicine, così lontane. Perché città e province votano in maniera opposta”, Il Sole/24 ore, 6 mars 2018.

Davide Mancino, Il voto ai partiti, il lavoro e il titolo di studio: esiste una correlazione?, Il Sole/24 hore, 14 mars, 2018.

Daniele Marini, “Il Nord a due velocità è arrabbiato con la politica”, La Stampa, 14 mars 2018.

Seymour Martin Lipset, Political Man. The Social Bases of Politics, New York, Doubleday, 1960.

Vittorio Mete, “Calabria a 5 Stelle”, Il Mulino, 16 avril 2018.

Michel Offerlé, Les Partis politiques, Paris, PUF, 2002.

Luca Orlando, “Da Sassuolo a Lecco, i distretti con la Lega. Bassi salari e lavoro la leva dei 5 Stelle al Sud”, Il Sole/24 ore, 7 mars 2018.

Adriana Pollice, “Barra e Scampia, il miracolo 5 Stelle parte dalle periferie”, Il Manifesto, 22 mars 2018.

Adriana Pollice, “Pomigliano, il ciclone Di Maio sulle ceneri della Fiat”, Il Manifesto, 22 mars 2018.

Adriana Pollice, “Castellammare. Il cantiere langue e la povertà dilaga, ma il centrosinistra non se n’è accorto”, Il Manifesto, 22 mars 2018.

Robert D. Putnam, Robert Leonardi, Rafaella Y. Nanetti, Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1993.

Francesco Ramella, “Il voto nelle (ex) regioni rosse dell’Italia del mezzo”, Il Mulino, 14 mars 2018.

Lorenzo de Sio, Matteo Cataldi, Federico De Lucia (dir.), “Le Elezioni politiche del 2013”, Centro Italiano Studi Elettorali, e-book, 2013.

Federico Tomassi, “Il voto a Roma alle elezioni politiche e regionali del 2018”, 29 mars 2018.

Carlo Trigilia, Gianfranco Viesti, “La crisi del Mezzogiorno e gli effetti perversi delle politiche”, Il Mulino, 1, 2016, p. 52-61.

Dario di Vico, “Ecco chi ha votato Salvini. Non solo i dimenticati. Anche i vincenti della globalizzazione hanno scelto la Lega”, Corriere della Sera, 18 mars 2018.

Gianfranco Viesti, “Il divorzio tra il sud e il centrosinistra”, Il Mulino, 23 avril 2018.