On the 16th of April, 2010, at the magnificent Teatro Arriaga in Bilbao, four hundred people took turns performing dramatic readings from the only novel written by the Basque-speaking French author, Jon Mirande1. Among the participants were the Mayor of Bilbao, Iñaki Azkuna, the General Secretary of the Nationalist Basque Party, Josune Ariztondo, a Socialist MP, Isabel Celaa, a specialist in Basque literature, Blanca Urgell, and the Bishop of Bilbao, Mario Iceta. Mirande had died in 1972, yet for decades the Spanish Basque Nationalists never celebrated his works, despite his unflagging passionate support for their cause. The reason for this reticence was because Mirande had been a fierce anti-Semite and outspoken admirer of the Third Reich. In one article, he had celebrated the 1328 Estella pogrom in Navarre as a manifestation of the proud Basque race confronting an outside threat. The National Basque Party’s sympathy for Israel, rooted in admiration for its national and linguistic achievements, helps explain why such a fervent Basque nationalist had been shrouded in silence in the Basque country up until 2010 2. The celebration that took place at the Arriaga Theater in Bilbao that year was a symptom of the amnesia, cynicism, and historical ignorance of the participants, local politicians, and local intellectual elite.

Jon Mirande, dreaming of the Basque ideal from Paris, enthusiastically backed the Nazi plan to carve up France in favor of the Basques and the Bretons. He believed in implementing the ideas of Obergruppenführer-SS Dr. Werner Best, who organized the 1942 deportations of the Jews in France, and was enchanted by the fascinating “Basquenfrage”3. Dr. Best admired the idea that “the Basques kept their racial purity by prohibiting Jews from entering the Basque country”. His lieutenant, Manchen, sent him a letter from the town of Biarritz, in the French Basque region, explaining: “from the ideological point of view, because the Basques and the Germans share the same racial principles, the Basques feel close to the new Germany. The Basques base their conception of the people on the blood that flows in their veins”4.

Recently, Spanish audiences have discovered how certain famous high-ranking Nazis believed that the Basque case was evidence for their theories of race. The recent rediscovery of the movie Im Lande der Basken, made in 1944 by the German Director Herbert Brieger, made a significant impact in Spain. The movie offered a mythical portrayal of the Basque people, with shots filtered through the language of Nazi propaganda. This was not the only German motion picture from the period on this topic, but it is the only one to survive in movie archives. The same director, Brieger, made a movie entitled Biscaya südwärts (The South of Biscay) in 1944, which has since been lost. In the surviving movie, the voice-over poses the central question that so preoccupied these specialists on race: “Where did this people come from? Nobody knows. Maybe from those who built the Tower of Babel, from the Phoenicians, from Atlanteans, the Finns, or the Mongols. In any event, the most popular theory says they came from the Iberians”5.

Herbert Brieger, Im Lande der Basken, 1944.

The racist underpinnings of Basque nationalism

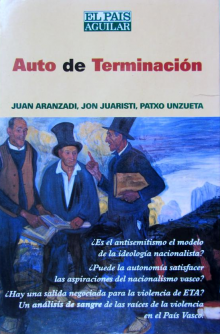

It is not surprising that the Basque question and Nazi history intersect here. In July 1993, a book was published in Madrid with the punning title Auto de terminación6. While evoking self-determination, it means “report of the end”. It was written by an anthropologist, Juan Aranzadi, a philologist, Jon Juaristi, and a political journalist, Patxo Unzueta. All three had been E.T.A. militants in their youth, or had had ties to it up until Franco’s death. The book was published by Aguilar-El País, a publishing house that belonged to the PRISA news corporation, which also owned the newspaper El País, ensuring it made a splash with the Spanish public. The cover of the book asks three questions: “Is anti-Semitism the model for nationalist ideology?”; “Can autonomy meet the aspirations of Basque nationalism?”; “Can there be a negotiated end to E.T.A. violence”? The book contains several chapters demonstrating the presence of an anti-Semitic element in the centuries-long construction of Basque political identity. In a chapter entitled What the Empty Ghetto Tells Us, Jon Juaristi writes “[…] the Basque anti-Spanish sentiment is, has, and always be –for as long as it exists– a form of anti-Semitism7. This shuttling back-and-forth between the Basque question and the Jewish question takes up half of Auto de terminación. This was at a time when the number of assassinations carried out in the name of Basque liberation continued to horrify the Spanish population: 25 in 1990, 46 in 1991, 26 in 1992. At the time, the head of the Basque government, the Lehendakari José Antonio Ardanza, a member of the Basque Nationalist Party, was promoting a policy of dialogue between all organizations rejecting terrorism. As if to counterbalance this political strategy of conciliation, the leader of the very same Basque Nationalist Party, Xabier Arzalluz, defended a radical ideology based on an ethnic conception of political identity. As indicated in the editor’s introductory note, Auto de terminación was an immediate response to a turning point in the political debate:

In 1993, Juan Aranzadi, Jon Juaristi and Patxo Unzueta published Auto de terminación.

“In 1993, some began once again invoking the existence of a separate and unique Basque race as an argument for demanding equally separate and unique political treatment”.

What was the editor’s note referring to? In early February 1993, six months prior to the book’s publication, the leader of the Basque Nationalist Party, Xabier Arzalluz, speaking a political rally in the city of Tolosa (in the Guipúzcoa province), had taken provocation to new heights. He had reaffirmed the importance of blood markers, that is to say the significant preponderance of blood [Type O negative] in the Basque population. He included these markers in a definition of Basque identity, and presented them as clearing a path to specific, legitimate political aspirations, asserting: “if, ethnically speaking, any nation truly exists in Europe, then it is the Basque nation”. He added that biological analyses proved that specific Cro-Magnon traits had survived only among the Basques8. By the early 2000s DNA sequencing had buried the hope of founding Basque identity upon physiological markers. But only a decade earlier it had still been possible to dust off and trot out the pseudo-biological language of nineteenth–century racism.

Arzalluz, a brilliant propagandist, provocateur, and formidable rhetorician, was the hard-line leader of the Basque Nationalist Party from 1980 to 2004. Following the outcry over the racist nature of this blood type argument, Arzalluz took advantage of the storm he had provoked. Two days after the Madrid and Barcelona press had denounced his reference to these biological ideas, he hit back in an article published in the February 7, 1993 issue of the Basque newspaper Deia. In this he referred disdainfully to his opponents as spokesmen for “Eternal Spain, a term taken from Francoist propaganda, and championed the activist Sabino Arana, founder of the Basque Nationalist Party in 1895, who stood rightly accused of having created an ethnic – even racist – conception of Basque identity9. In defending the political honor of its founding father, Arzalluz was affirming the very legitimacy of the movement itself.

Left: Sabino Arana and his wife, circa 1900.

Right: Xabier Arzalluz in a nationalist meeting (Batzoki May, 13th of 1979).

What was at stake here? Arana’s brand of Basque nationalism was based on his rejection of the migrant workers who had come to the Basque country to work in the steel mills and shipbuilding yards, and on an affirmation of the ethnic identity of the region's inhabitants. He designated the invaders as maketos, their society as maketería, and the political will behind their invasion of Basque society as maketismo. In order to draw a lasting distinction between the different populations, he deemed it essential to guarantee their rigorous segregation. This is why he accorded such importance to the issue of marriage, rejecting any marriage that would unite a pure Basque with anyone of maketa descent. He himself chose his wife only after checking the origins of her sixteen great-great-grandparents. In an 1895 article he wrote:

Today, when so many Bizkaino families are mixed with maketos, or Spaniards, thanks to Bizkainos who have already lost awareness of their nationality, we shall establish (if we are free to do so) a distinction between natives and mestizos, with regard to rights and to the places where they are permitted to settle; but someone of pure maketa race will ever be maketo, even if he is a descendant of seven generations born in Bizkaya, and a speaker of Euzkera10.

In this passage, the expression in parenthesis “(if we are free to do so)” has a very specific meaning: if the Basque country were to regain its political sovereignty. His plan would have involved a statutory distinction (or separation) and the placing of limits on where certain populations could reside. But what is most striking is his definition of Basque. This has nothing to do with how many generations a family has resided in the Basque country, but depends solely on its natural maketa or Basque origins. This rejection of socio-historical, cultural, and even environmental factors in the definition of national identity was a trademark of Sabino Arana's thought. The 1895 article is not polemical or rhetorical overreach, but the very basis of his worldview, as can be seen in a passage from a different article published the same year:

to be born in one place or another does not mean anything, as is clearly the case with regards to race. A child of Bizkainos born in Madagascar or Dahomey will be as racially Bizkaino as anyone born in Olakueta; in turn, a descendant of Spaniards born in Bizkaya will never be racially Bizkaino.

Dióscoro Teófilo Puebla y Tolín, Primer desembarco de Cristóbal Colón en América, 1862, Museo del Prado.

He made no secret of the fact that these views served a dual purpose. First, they reaffirmed the irreducible alterity of migrants of “Spanish” or “maketa” descent who had settled in the Basque country. Second, they reassured the Basque communities who had left for Mexico, Argentina, Cuba, and various other New World republics, including the United States –reassuring them, of course, so as to rally them to the Basque nationalist cause. This was of great importance, because the last decade of the nineteenth century saw the celebration of the Hispanic “race” spread ever more rapidly in Spain and a number of Latin American republics. The Día de la Raza, held on the October 6th holiday, celebrates what the founder of the Spanish Falanje Nacional-Sindicalista, José Antonio Primo de Rivera, would later call a “unity of destiny in the universal” (unidad de destino en lo universal). This concept was a way to exalt the unitary universalism of a Hispanic-ness that had managed to impose a single, intransigent, Catholic faith upon diverse populations, as evidenced by Leo XIII’s encyclical of July 16, 1892, Quarto Abuente Saeculo11. Defending the Spanish race would therefore have exerted a powerful attraction, including among Basques in Europe and the Americas. In this context, radical Basque nationalism felt a need to assert a racial incompatibility between the Basque subgroup and the Spanish whole. To use the language of today, this was an ideological and political contest within an ultra-reactionary current. Likewise, in the late nineteenth century, a racial definition of the Basque identity expanded while Spaniards attempted to define their own identity in a racial way. Two symetrical projects therefore12. This is why Sabino Arana, in an article published in 1899, advocated a strict separation within Basque society:

It is, therefore, clearly and plainly evident that the salvation of Basque society, its regeneration and its future hope, depend on the most absolute isolation, on the removal of every foreign element, on the rational and practical exclusion of everything that does not clearly bear the fixed and indelible imprint of pure Basque origins13.

Arana’s observations, whether he wished it or not, partake in a larger moment of introspection affecting Spain as a whole, centered on a feeling of collapse on losing its last remaining distant colonies (Cuba, Puerto Rico, and the Philippines) in 189814. His arguments employ two semantic registers: political apocalypse and racial difference. He seeks to portray himself as sounding an alarm before it is too late – which is to say before intermarriages between pure Basques and migrants from the rest of Spain irrevocably muddy the bloodlines. In these circumstances, it would have been surprising if he had not used racial terminology, which at the time had not fallen into the disgrace that would befall it after the tragedy of Nazism. In 1894 he wrote:

Your race – unique because of its beautiful qualities, but even more so because it does not have any contact points or fraternity with either the Spanish race or the French race, which are its neighbors, or with any race whatsoever in the world – is the one upon which your Bizkaya Fatherland was founded. And you, without a shred of dignity or respect for your ancestors, have sullied your blood with Spanish or maketa blood, mixed and consorted with the vilest and most despicable race in Europe, and you seek for this debased race to replace your race in the very territory of your Fatherland15.

The key point here is the designation of the non-Basque Spanish population as the “vilest and most despicable race in Europe”. Here is where the Basque question and the Jewish question intersect in Arana’s political worldview. Because, according to a long tradition of intransigent Catholic thought to which he was firmly beholden, the traces of Jewish – as well as Muslim – villainy had never been washed away, thus abasing the Spaniards in comparison to the populations of the rest of Europe. Throughout the sixteenth century and beyond, polemicists (both Catholic and Protestant) who were hostile to Spain never tired of repeating the same argument: Spain and the Inquisition were barbaric because the regime was tyrannical and because its population was composed of mixed-bloods, half-Jews, half-Moors. What is more, the defense of Basque identity was founded on the conviction that the Bizkainos, to use the language of both Arana and earlier writers, never allowed the converted Jews or Muslims to intermix with them:

While the Spanish race was never a race, but an amorphous product of the admixture of several and different peoples, there are Bizkaino laws of a foundational nature, inspired by the natural repulsion that Bizkaino families feel toward the idea of mixing with foreign families, since they had a relatively clear awareness of their primordial and unique race. […] Hence while the presence of the words “Moors” and “Jews” in Spanish legislation must always be understood as expressing religious affiliation, their presence in Bizkaino laws, on the contrary, is more likely to reflect an idea of race than the spirit of religion16.

Here we can intuit Arana’s sense of competing with the notion of defending the Hispanic “raza”, which was in vogue to varying degrees at the time he was writing. Here the “amorphous product of the admixture of several and different peoples” that was the Spanish population did not refer to intermarriage with Gascons, Neapolitans, Aragonese, or Portuguese, but specifically to Jews and Muslims. And for Arana, it was important that there be no doubt that this rejection of the Jewish or Moorish element by the Basque people was racial, not religious.

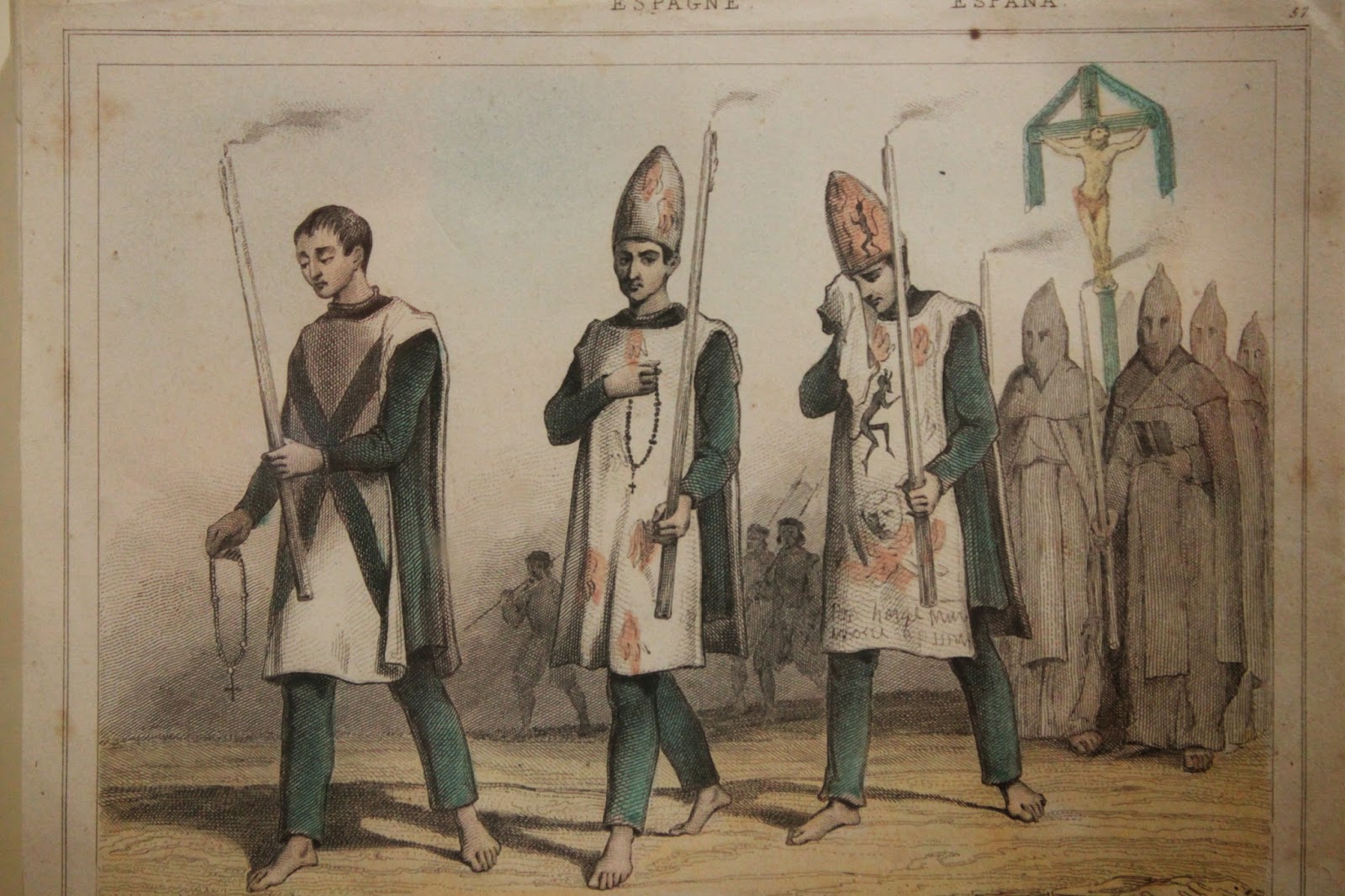

Men condemned to wear the San Benito.

Championing Arana’s ideology

Almost a century later, his distant and faithful successor, Xabier Arzalluz, in his February 1993 article cited above, sought to present Arana's rhetoric as simply typical of his time. On this point he is not wrong. The intermixing of these different registers was quite commonplace at the time: ethnic identities, racial profiles, linguistic differences, cultural heritages, and political traditions, were all too often grouped together in the nationalist logorrhea infecting late nineteenth-century Europe. Arzalluz takes the accusation that Basque nationalism was the cradle of a radical form of racism on turns it on its head. He argues that anti-Jewish and anti-Muslim segregationist sentiment in Biscay was simply an extension of the segregationist ideology present across all of Spain in the early modern period. But before we examine this argument, which is stronger than it might initially appear, I would like to pause a moment longer over the close relationship between the construction of the Basque question at the turn of the twentieth century, on the one hand, and the Jewish question, on the other.

In fact, there was nothing original about Sabino Arana’s ideas. He simply gathered various commonplace statements and lent them a hysterical tinge. In 1911, nine years after Arana’s death, the Basque intellectual Luis de Eleizalde published a thin volume, Raza, lengua y nación vascas, which saw Arana’s legacy as part of a commonplace tradition:

In Biscay a law was passed that in order to become a citizen, not just a resident, people either needed to demonstrate their racial roots or be foreign with a proven record of no forefathers from either the Jewish or the Muslim caste. This law, as noted by Master Arana Goiri’tar Sabin, remained in place well into the nineteenth century17.

Here, the focus of exclusion was not on the foreigner in general, so much as those unable to prove they were not descendents of Jewish or Moorish converts. In other words, the “maketos” or Spaniards were considered more undesirable than other potential foreigners, because from the perspective of the dominant tradition of blood purity they were seen as more suspect. Of course, this political language also served another purpose. It excluded proletarian immigrants from the central or southern regions of Spain, since they belonged to the “maketería”, whilst welcoming the arrival of British engineers and German chemists.

Blast furnaces, Bilbao, 1890, photograph, 1890, Hauser y Menet.

This distinction between different types of migrants was based on the idea that Spanish society had been Judaized, with the exception of the Basques. This notion dates back to the sixteenth century:

With regard to the Semitic element, we have already seen in a previous chapter its important influence in the ethnic makeup of today’s Spanish people. Such influence is absent from the Basque race; this race has not received any Semitic infiltration whatsoever. In Biscay, Gipuzkoa and highland Navarre, there has never been any trace of a Hebrew population18.

So supposedly there was no Semitic infiltration among the Basques and Navarrese, at least not those in the mountains, as it would have been difficult to deny the glorious history of medieval Judaism in Navarre. The following passage should be sufficient to quell any remaining doubts as to the racial reason for defining Jews as a source of impurity, and the Basques as a pure population:

[…] with regard to the Hebrew race, things in Euzkadi were very different from the rest of the peninsula. Beyond the Ebro, Spanish society welcomed the conversos with open arms, allowing them to reach the highest echelons of church and state. In Navarre, the courts decreed that conversos were not eligible for certain civil and ecclesiastical offices and could not receive their revenues, and the Navarrese people always held conversos in contempt, shying away in horror from the idea of mixing their blood with them. The lowliest Basque taxpayer would have thought it dishonorable to allow a Hebrew wet-nurse to nurse his children. […] Basque people have always felt an instinctive repugnance towards mixing their blood with foreign blood, as if they sensed that their greatest treasure, after the purity and integrity of the Catholic faith, was the immemorial purity of the race. Mestizaje is relatively new to Euzkadi, and not very common; even today, ninety percent of those born in Euzkadi are pure-race Basques19.

In a 1904 lecture, another local intellectual, Mariano Arigita y Lasa, addressed the question of the presence of Jews in the Basque Country, seeing it as essential to determining the future of Basque identity. This short text complements Eleizalde’s beliefs:

The people never loved the Jews, and if they coexisted in the social sphere this was due to the law of necessity, which made people seek Jewish help when in dire financial straits. But the people never partook in the Jews’ racial qualities, and they never mixed their blood with Hebrew blood, which they always regarded as base. Finally, the presence of Judah’s offspring in the Basque Country for so many centuries had no influence on the customs or way of life of the natives of the very noble Basque Country, whose social education was based on nobility, hidalguía generosity and honesty, which frankly are genuine characteristics of the people of Euskadi, but unknown to the foreign schemers who were forced upon our land by an unspeakable and execrable crime, and whose life was made tolerable only thanks to our forefathers’ proverbial hospitality20.

Map of Basque Country and Asturias, XVIIth century.

Thus with Arigita, as with Eleizalde, we find the same physiological references to a Jewish infection against which the Basques, unlike the Spaniards, were able to defend themselves. In this case, the means of contagion was neither impure blood nor sperm, but the milk of Jewish wet-nurses that was not allowed to sully the lips of the babes of Biscay:

In this regard the Basques were so intransigent – kings and magnates, nobility and commoners acted in such unison – that though they relied on the services of Jews and Jewesses for medical purposes, and for the delivery of their babies, there is not one single recorded case showing any Basque ever let a Hebrew wet-nurse care for his children, as if they were afraid of contaminating the blood of their descendants if they allowed it to be mixed with the breast milk of the Jewesses21.

The long anti-Semitic genealogy of Basque particularism

These flights of fancy no doubt partake in the nationalist frenzy that gripped Europe in the second half of the nineteenth century, taking openly racist form in the German völkisch movement and Arana’s Basquism for instance22. But in the case of the assertion of Basque singularism, the racial dimension to this political claim is rooted in a past far predating the formation of nation states in the nineteenth century23. The wet-nurse example helps us understand a mechanism that the sixteenth-century Spanish had incorporated into their social stratagems. It was presumed that the populations of the Basque country, Cantabria, and the Navarrese Pyrenees had not been “sullied” through mixing with Muslim invaders or Jewish communities24. They therefore benefited from a kind of general blood purity that – and this is the key point – did not have to be proven. This advantage led the Basques to assert the “universal nobility” of their entire population25. They were all purportedly noble because they were pure-blooded, whereas in the rest of Spain the blood purity of certain families allowed them to assert the nobility of their lineage in contrast to families suspected of shameful intermixing. Here is how, in 1607, Baltasar de Echave defined the extraordinary privilege of the “universal nobility” of the Basques:

Although they have intermixed among themselves, some families transforming into different ones, it is of no great import, since, being of a single kin, and sharing relatives, it is the same people who succeed each other in the same solares and houses, even if it is through the purchase of said solares and houses; for as these provinces are close to each other and isolated from the rest, they have not allowed for any intermixing, in general or in particular, with any foreign people or nation, people of unclean blood or those who are not hidalgos […] from which it follows that they are all relatives with each other […] and all of these houses and solares do not just belong to known hijosdalgo of the blood, and of known household, but also and above all these Provinces are themselves a single known and recognized household of noble hidalgos; and this is so true that simply proving one’s descent from parents and grandparents native to the two Provinces of Vizcaya and Guipúzcoa from time immemorial is sufficient to file executoria […] and for them to be deemed hijosdalgo of the blood, of known household26.

♦ From Mexico where he settled as a painter, Baltasar de Echave asserts the purety of his native Basque province. The collective nobiliary privilege was based on the conviction that the Basque territory had never been contaminated by islamic or jewish migration. In Baltasare Echave's treaty, racial and linguistical genealogies are intertwined: the basque language would had been imported from Tubal, Noe's grandson, and first inhabitant of the province ♦

Baltasar de Echave, Discursos de la antigüedad de la lengua cantabra bascongada, Mexico, Henrico Martinez, 1607.

This is why families residing in other regions of Spain would sometimes invent false Basque or Cantabrian genealogies. Some attempted to purchase a house in the region, in order to present it as the residence of their ancestors. This is why Articles XIII and XIV of the first Title of the Fuero Nuevo of Biscay (1526) prohibited conversos from acquiring property or setting up residence:

all men of Vizcaya are hidalgos of noble lineage, and pure blood, and thanks to your high graciousness enjoy royal decrees forbidding recent converts, Jews, Moors, and the descendents of their lineage from living or residing in Biscay27.

and the law 14:

certain persons among recent converts to our Holy Catholic Faith, Jews and Moors and their lineages, due to their fear of the Inquisition and so as to claim they are not lowly but say they are hidalgos, have come and are coming to my kingdoms and seigniories of Castille, to live and reside in the towns and villages of the county and seigniory of Biscay; if a stop is not put to this it could result in harm and inconvenience against God’s and my service28.

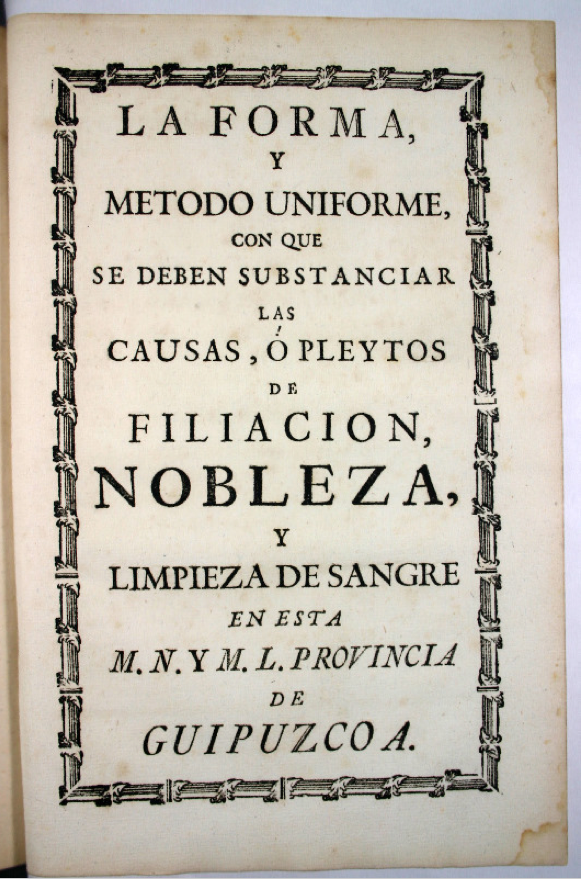

Evidence of these phenomena can be found in the records of thousands of sources which are kept in the archives of the Inquisition, the military orders, and the nobility section of the high courts in Valladolid, Granada, and Seville. The privileges granted to Biscay were extended to neighboring Guipúzcoa in 1610.

Rural house with its blazon (Biscay), Felipe Manterola (1910-1920).

These legal statutes were accompanied by the production of an ideological corpus, whose principal authors were the engineer and philologist Andrés de Poza30, and the historians Zaldivia and Garibay. From the mid-sixteenth century onwards, their writings built up the theory of the absolute singularity of the Basques, reinforcing the presumption of purity they were granted by law. Thus Poza wrote the first essay on the origins of the Basque language and a treatise on the universal nobility of the Basques. In the latter he emphasized the importance of a genealogical understanding of the Basque character:

There is no beginning or end to the nobility of Biscay, and it may be said of it (without lying like the Athenians, who claimed they were as old as the earth they walked on, nor the Arcadians, who said they appeared thirty thousand years before the moon appeared in the sky) that it has truly retained its freedom, its tongue, and its customs since Patriarch Tubal down to the present day. [...] In conclusion, the natural Biscayan originating from the province of Biscay has every reason to state they are of noble blood since time immemorial through to the present day (except for bastards and other such illness)31.

Reasoning of this kind can be found in the manuscript records of the older jurisdictions. We can find it in the treatises written at the time, affirming the singular status of Basque and Cantabrian populations. From this rhetoric we can see how, from the perspective of sixteenth- and seventeenth-century political institutions, it was impossible to make a distinction between religious faith and racial purity, as two distinct spheres of human experience. A passage drawn from the Suma de la cosas cantábricas y guipuzcoanas by the historian Juan Martínez de Zaldivia (1560) offers an example of how intertwined they were:

Even rustic fellows and shepherds take pride in the purity of their blood and their lineages, and they especially boast of having always been far removed from heresies, from Jews, Moors, and other infidels, and of never having intermixed, and of always having kept the Christian name pure. And if any Jew traveled to that land on business it was forbidden to them to linger in any given place for more than three days or for more than thirteen days within the region, from which followed that, when young men heard the very word “Jew”, they were no less frightened than on hearing of another species different from humans, and to this day they reserve the privilege of prohibiting any of the Jews newly converted to our sacred Catholic faith from inhabiting that land32.

Typical treaty on the collective nobility in Gupuzcoa, Francisco Antonio de Olave, 18th century.

The Enlightenment built on this ideological and legal impetus viewing Basque exceptionalism and its attendant privileges as issuing from the absence of pollution by Jews or Muslims. For the Jesuit Manuel de Larramendi, writing in the first half of the eighteenth century, Basque exceptionalism was to be demonstrated primarily by invoking the purity and intransigence of local Catholicism:

The Moors flooded Spain, but Mohammedism did not enter Guipuzcoa. Ever since Christ’s gospel has been preached there, Guipuzcoa has received and always preserved the apostolic Roman Catholic faith, without a single case of a Guipuzcoan apostate heretically becoming Jewish or Moorish 33.

But the Basque purity of Guipuzcoa is not solely a matter of loyalty to the faith, for it also involves a racial dimension:

they belong to the oldest nation in Spain […] a little nation that has not mixed, that has no race [raza] of Moors, Goths, Alans, Silings, Romans, Greeks, Jews, Carthaginians, Phoenicians, or other nations said to have come to Spain. It is a small, clean nation, free of any sullying of blood, lineage, or genealogy34.

Larramendi’s argument is wholly logical. He sets out the measures adopted in Castille relating to purity of blood, together with steps taken by the Council of Orders to ensure that only subjects with faultless pedigree became knights in a military order. He points out that these were intended to allay the risk of “villeins, Moors, Jews, Negroes, and mulattos” assuming leading social positions. He further states that “there is absolutely no risk of this in Guipuzcoa”35.

The jurist Pedro de Fontecha y Salazar, in his 1749 treaty on the legal definition of the Basque polity, goes over the provisions of the Nuevo Fuero forbidding the descendants of converts from residing permanently on land in the seigniory of Biscay. He introduces no distance between the rhetoric in use in the sixteenth century, and the time when he is now writing his summary:

The seigniory of Biscay, with the ancient firmness its inhabitants are known for, and its naturals being of very famous and recognized nobility, will undergo great harm were they to accept that people of such vile, foul, and ignoble condition reside amongst them. For the ascendants and descendants of Jews and Moors who have and are unable to acquire any nobility are well known amongst all nations. And should the parents or grandparents of any amongst them have converted, experience proves they are a not constant in their faith, not loyal towards their king, but traitors guilty of human and divine lèse-majesté, and their conversation and communication could do great harm to naturals36.

As this assortment of texts has demonstrated, the cultural construction of Basque political identity is seamlessly rooted in textual traditions dating from the turn of the sixteenth century. It brings out the existence of an intellectual genealogy owing nothing to the emergence of Herder’s anti-universalism or to the Romantic concept of a nation. At most one may note that the Napoleonic invasion and, later on, the three Carlist civil wars, precipitated the amalgam between, on the one hand, ancient particularism, and, on the other, demands for institutional separation in response to the advances of liberalism in nineteenth-century Spain37.

Manuel Salvador Carmona, The engagement supervised by the rabbi, 18th century

Let us now return to Xabier Arzalluz, the former leader of the Basque Nationalist Party, whose 1993 article set out a different perspective on the racism of Sabino Arana and other advocates of blood purity. Like any good cultural historian, he sees Arana’s language within the context of the political culture of his era:

All Sabino Arana did was apply the “nationalities principle” which was in vogue at that point throughout Europe, to the Basque case. Hence the issue of family names was, at its origins, a “Spanish” demand for blood purity rather than an expression Basque arrogance. And in order to uphold the “status” requested by the Law of Castile, the Fuero prohibited Moors, Jews, blacks and people of impure blood from becoming vecinos.

This passage is the strategic crux of a virulent and ironic essay that Arzalluz flung at his adversaries. The argument runs as follows: the sixteenth-century Basques simply took advantage of the fact that the institutions and power structures of Spanish society discriminated against the descendents of converts in their midst. The blood purity statutes that designated the undesirable element throughout Spain, also thereby designated Cantabria, Navarra, and the Basque country, as a refuge and reservoir of blood purity for all of Spain, a reservoir that was useful to all and as a source of purity by all, not only by the Basques, Navarrese, and Cantabrians. On this point, Xabier Arzalluz is entirely correct: if the Basque question became a site of racial discrimination, it was in response to a purity requirement emanating from the rest of Spain from the fifteenth century onwards.

Basque purity and Spanish purification

The quotes from late nineteenth-century texts given above, especially those by Sabino Arana, illustrate the extent to which the construction of Basque identity was underpinned by the argument of racial purity, in contrast to a Spanish population unable to fight off Jewish and Muslim infection. But it would be altogether unfair and inaccurate to claim that this unselfconscious anti-Semitism was, both then and in the twentieth century, confined to the narrow circles of Basque nationalism. Perhaps contemporary Spain itself offers a good example of what might be called “anti-Semitism without Jews”.

Nineteenth- and twentieth-century Spain, despite its political instability and strategic setbacks, did not avoid international developments in racist thought. As Joshua Goode has shown in his work on racial thought in present-day Spain:

This view of the nation as comprised of spirits, traditions, and history, combined with the modern biological assumption that elements of identity are passed down physically through the millennia, remained a constant leitmotif among Spanish intellectuals of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries38.

Rock Painting, Altamira caves, Cantabria.

In fact, Spanish scientific debates surrounding archeology, physical anthropology, and the theory of evolution were deeply embedded in late nineteenth-century international discussion. Spanish intellectuals attended international congresses on the origins of human populations. The discovery of pre-historic art in the caves of Altamira in Cantabria, together with the mystery of the origins of the Basques, gave Spanish scientists an opportunity to play a central role in many early twentieth-century anthropological debates in the early twentieth century39. Contrary to the ideas produced by earlier slave societies, and by European colonial empires in Africa and Asia, Spanish racial thought focused on the composition of Spanish society itself. According to Joshua Goode:

Spain’s problematic nineteenth century, defined by civil wars, political and military insurrections, and an endemic regional problem, led most racial thinkers to be more concerned with the enemy within than the enemy without40.

This is not the place to examine in detail the history of reactionary anti-Semitism in contemporary Spain; several studies have done an excellent job shedding light on these phenomena41. Yet one element that might attract our attention is the persistence, in this Judeo-phobia, of themes carried over from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. I do not wish to focus here on the important distinctions between the discourse and administrative enforcement of Jewish exclusion as this transpired during the Civil War and under the dictatorship. I would prefer to reflect on the longevity of certain types of arguments.

And the racial question was asked openly, even if the answers given differed from the Nazi model42. Among the various phenomena we could usefully examine, one deserves a little more attention than the others. This was the medical, or more specifically psychiatric literature seeking to make sense of the crisis in Spanish society during the Civil War43. Several authors presented adherence to Marxism as a degenerative psychosis, and attempted to offer descriptions of the physiological terrain conducive to this illness. The answer was to be found in the mixed racial inheritance of Spain's long history. As the psychiatrist Antonio Vallego Nagera wrote:

Today, as much as during the Reconquista, we Hispanic-Roman-Gothic people struggle against the Judeo-Moors. The pure racial core against the spurious one. […] The Marxist Spanish racial core is Judeo-Moorish, a blood mixture which psychologically sets it apart from the foreign Marxist, the pure Semite44.

If the Spanish population, though seemingly unified, was in reality divided into two irreconcilable camps, it was precisely because the assimilation of Jews and Muslims had been fraudulent, as Nagera goes on to explain:

The conversion of Jewish families was faked, an act of convenience, an adaptation to the circumstances. […] Their submission in Christian Jordan did not change the spirit of the race, did not transform their ancestral Semitic psychology, their characteristic avarice, falsehood, philistinism, and evil. […] And when the revolution came, under the guise of a republic, the converso made his intentions clear, tearing apart the vital nodes of Christian society, murdering, robbing, raping, and perpetrating all manner of excesses.

Antonio Vallejo Nájera, was a teacher of Psychiatry in the Military Sanitary Academy and director of the psychatric services under Franco's dictatorship. He was convinced of the existence of communist genes.

Amidst the chaos of the Civil War, another famous Francoist psychiatrist, Juan José López Ibor, asked the opposite question: what was the source of the heroism of the healthy portion of the Spanish population, who saw the caudillo as the savior of their homeland. He wondered where the good Spaniards had drawn their valor to resist the poisons of the republic and of Marxism. He too made use of explicitly racial terminology in providing his answer:

There is no doubt that racial and social factors have an influence here. I am in turn firmly persuaded that the expression “the Spaniards’ spiritual reserve” is not a myth. There is something in them that keeps them upright in adverse circumstances. Perhaps it is their inherent biological conditions – race –, perhaps their [own individual constitution]45.

Let us take the following emblematic example of Generalissimo Franco’s speech in Madrid on May 19, 1939, the day of the nationalist victory:

Judaism, Freemasonry, and Marxism, were hooks planted into the body of the nation by the leaders of the Popular Front, who obeyed orders that came directly from the Russian Comintern. Let us make no mistake: the Jewish spirit that is so adept at colluding with the anti-Spanish revolution cannot be extinguished overnight, and it continues to draw breath in the depths of many souls46.

May 19th of 1939's Victory parade of Franco's forces

What is interesting here is the resonance in Spanish memory of the idea of a Jewishness that could not be extinguished overnight, and that continued to reside in the depths of certain souls. This chimes almost perfectly with the spirit that, in the late fifteenth century, led to creation of a new Inquisition court. The impetus behind this was the suspicion that Judaism and Islam might continue to beat in the hearts of families who had converted, willingly or under duress, to Christianity.

Spanish society, exhausted by three years of civil war, and having remained on the sidelines during World War II due to Franco’s policy of neutrality, did not share other European societies’ recognition that the Jews had suffered unparalleled extermination. The surest sign of this was the social acceptability of anti-Semitism, which continued unabated from the pre-war to the post-war period. Franco’s regime, in order to join the United Nations, gradually eliminated all overt anti-Semitism in official pronouncements. But to take just one example, this did not prevent Luis Marquina from directing the 1952 film Amaya o los Vascos47. The movie was inspired by a historical novel by the Navarrese writer Francisco Navarro Villoslada, Amaya o los Vascos en el siglo VIII, published in 187748. The author, both a Carlist and a Navarrese traditionalist, hails from the pre-history of modern Basque nationalism. His novel addresses themes that are fairly similar to the question studied here. He offers a portrayal of Navarre – and, by extension, Spain – during the eight-century Muslim invasion. The book distinguishes between four population groups: the Visigoths (i.e., the Spain that was unable to resist), the Basques (i.e., the peoples who escaped Moorish domination), the Muslim Moors who came from Africa, and the Jews, who had everything to gain from a Muslim victory and therefore betrayed their country. The scenes in the 1952 film depicting the Sanhedrin of Pamplona might easily be mistaken for scenes in movies by Nazi filmmakers, such as Veit Harlan's Juif Süss49. The final scene depicts the search for a traitorous Jew in the streets of Pamplona as a joyous festival for the Basque-Navarrese people. The release of this film did not prevent Spain from joining UNESCO, under pressure from President Eisenhower, that very same year50.

Amaya o los Vascos, by Luis Marquina, 1952

Beyond Francoism

The fact that ideological holdovers from the 1930s survived into the Franco regime is not especially surprising. It is, however, far more surprising to realize that traditional anti-Semitism was expressed by the exiled Spanish intelligentsia. The most famous case is that of the medievalist Claudio Sánchez Albornoz, President of the Spanish government in exile from 1962 to 197151. In the great tome he published in Buenos Aires in 1957, Spain: A Historical Enigma, he was responding, as is well known, to Américo Castro's book, The Historical Reality of Spain, published three years earlier in Mexico. Castro saw Spain's uniqueness as issuing from the intersecting influences of the Christian, Jewish, and Muslim populations co-existing and confronting each other on the Iberian Peninsula. He denied that anything like a Spanish identity existed prior to the 11th century. In rebuttal to this theory, Sánchez Albornoz, a specialist in the history of medieval Asturias, rooted Spanish identity in the ruling Gothic culture, marginalizing the Muslim and especially Jewish contributions to the formation of Spanish-ness. This debate caused a great deal of spilt ink, and is not crucial to us here, except to the extent that Albornoz's book sheds light on just how acceptable anti-Semitism was in Spanish society at the time. In the 1973 edition published in Spain by Edhasa, there are many passages similar to the following two. The first, which apparently confirms Franco’s speech above, asserts that Jews who converted in the fifteenth century did not really change their character after having changed their religion:

Most conversos stayed loyal to their Jewish faith; they did not change their characteristic habits overnight, of course, they did not give up their love of lending, of finance and commerce, and since as new Christians they acquired the rights and privileges of old Christians without changing their way of life or their faith, the Spaniards realized in the fifteenth century that the hated Jews were now able to continue extorting them and exploiting them as before, and not just from outside their social leadership but now from within and without their ranks. Their false brothers in the faith were now able to govern over the Spaniards from the positions of power that they had secured in municipal governments and close to the King52.

Claudio Sánchez Albornoz, Spain a Historical Enigma, 1957

In this passage, this comrade-in-arms of Manuel Azaña deploys the battery of accusations leveled against the conversos by the Grand Inquisitors and by supporters of the statutes of blood purity in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. It is all there: the insincerity of the conversions, and the fraudulent use of the new Christian status to secure positions of power in the cities and kingdoms. But the medievalist went much further still, drawing up a balance sheet of the history of the relationship between Spain and its Jews. He constructed a symmetrical history of two equally intense persecutions.

When the moment comes to examine the details of the damage they inflicted on Spain in every matter within their reach – from espionage to the financing of military enterprises – during historic and decisive moments of her modern history, and when records emerge of their persistent violent hostility towards all things Hispanic throughout the centuries […] then it will become clear why I speak of scores settled. Our persecution of the Hebrews and their converso children on the one hand, is balanced out, on the other, by their exploitation of the Spanish people during the Middle Ages, their shadowy legacy inside Spain upon their departure and their fury after their expulsion53.

To truly understand the significance of this passage, we must remember that it was written after the Holocaust – a sign of the virulence of the author’s anti-Semitism. Or of the complete blindness in Spain to what had shaken Europe so heavily from 1938 to 1945. Or both.

At the end of the dictatorship, repressed memories of the Jewish presence welled up unrestrained, in a joyous mix of fantasy, fictive memory, desire to re-establish links with a defunct Jewish world, and a determination to latch onto Judaism as the obverse to the national Catholicism of Franco’s regime (along perhaps with its unwavering proclivity for Arabism). Historian Danielle Rozenberg is eloquent on this topic:

Nowadays, many Spaniards are interested in ethnic intermarriage in their villages and regions, as well as in the origins of their patronymic. Jewish communities in the Peninsula are often consulted about these matters and, in the absence of any evidence one way or the other about a hypothetical Jewish ancestor, many people like to imagine that they did indeed have a Jewish ancestor54.

But this fantasy, which became widespread after Franco’s death, did not seem to have much of an impact on contemporary opinions. In fact, the memory of the Holocaust and of World War II was far weaker in Spain than in any other European country. On this subject, on the eve of its joining the European Community (in 1986), opinion in Spain was even further from that in France than was opinion in Poland or Romania. As Alejandro Baer highlights in his study of how Sephardic Jews have been forgotten in present-day Spain: “when Spain finally emerged from the grip of Franco’s dictatorship, the country’s democracy was rebuilt on the margins of the prevailing European value system, in which the memory of Auschwitz and the concentration camps occupy a central place” 55.

Without this marginal position it would be harder to explain the deceit perpetrated by Enric Marco, the pretend former deportee, recounted by Javier Cercas in his book The Impostor56. I also remember the extraordinary impact when Holocaust, an American television series by Marvin Chomsky, was aired in June 1979. Coming after over thirty years of Spanish silence on the subject, it felt like a bolt from the blue. The day that the fifth episode aired, June 29, 1979, the Spanish neo-Nazi group CEDADE (Spanish Circle of the Friends of Europe) launched a campaign of posters denouncing the series57. They referred in a press release to “the myth of six million deaths”, and accused Spanish television of having scheduled the airing of Holocaust so as to prepare public opinion for Spain’s upcoming official recognition of the State of Israel. Faithful to the Francoist tradition, the Spanish neo-Nazis were vehemently opposed to the idea of establishing relations with Israel. The series had been purchased in 1978 and was originally scheduled for January 1979. Its broadcast was suspended sine die. An article in El País offers an account of the suspension, in terms reflecting the persistence of anti-Semitic language, even in the pages of this center-left pro-democracy newspaper:

We imagine that this decision was made due to the controversy that arose surrounding the made-for-TV movie QB VII, which was considered Zionist propaganda, and defended by the Jewish community. Holocaust, like QB VII, is an indisputable sign of the power of Jewish capital in the North American movie industry58.

Holocauste's poster

The tone is quite removed from that of the CEDADE neo-Nazis, but not all that different from the literature inspired by the Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which was commonly found across Spain during the 1920s and 30s59. Every other country in Western Europe, as well as all those in the Soviet bloc, had recognized Israel in 1948 and 1949, even if some of them had severed relations after the Six-Day War. Spain alone had not recognized Israel. The year it joined the European Community, the socialist government of Felipe Gonzalez made the leap and recognized Israel, after both the dictatorship and the conservative transition government had refused to do so. This was more than sufficient to fuel the paranoia of the CEDADE activists.

Nowadays, and however regrettable this may be, it is impossible to wholly separate the Jewish question from that of Israel in public debate. This is as true in Spain as elsewhere. Hence two of the authors who edited and contributed to the volume Auto de Terminación in 1993, later had a falling out, not over the Basque question, but over their relationship to Judaism. Jon Juaristi, philologist, poet, and director of the National Library of Madrid, later converted to Judaism. As a public intellectual, he took up the defense of the (continued) existence of the state of Israel . And he did so in a country like Spain, where the majority of public opinion is either critical or hostile towards Israel, and where there is a great deal of sympathy for the Palestinian cause. Whatever personal motivation Jon Juaristi had for converting to Judaism (and I certainly do not claim to know all his motives), the adoption of Jewish identity by a son of the Basque bourgeoisie from Bilbao and a former E.T.A. militant should be understood in relationship to this legacy and this trajectory. To become Jewish, in these circumstances, comes down to turning one’s back on the deepest and most secret core of Basque exclusivism. This is an ironic thumbing of the nose at five centuries of phantasmagoria, five centuries of the assertion of a specifically Basque purity based on the absence of any Jewish element. For his part, Juan Aranzadi, professor of social anthropology, saw the Jewish question from two altogether different angles. Like Juaristi, and many others, he did not fail to emphasize the important role the fantasy of blood purity had played in the genesis of Basque identity. However, he also observed the Judaism question in asserting that, as of the sixteenth century, the ethnic and religious construction of Basque Catholics followed the model of the chosen people. He was well aware that the Basque Nationalist Party, post-World War II, overtly admired the accomplishments of Zionism (a sovereign state, a resurrected language). As such, he put forward the idea of a parallel history of Basque political hysteria and the irrationality of political Zionism, both of which he condemned with the same polemical vigor. In truth, this parallel has a very long history in intellectual debate in Iberian countries. We are well aware that the doctrinal intransigence of the Inquisition and the ideology of blood purity primarily and overwhelmingly targeted the descendents of Jewish and Muslim converts. But religious intransigence and a refusal to intermix were often interpreted as the transposition into Spanish Christian society of social mechanisms and norms from the Jewish world. This was even a commonplace in the most reactionary Spanish historiography of the Franco era that while appreciating that the Inquisition was a useful tool of political and spiritual cohesion, interpreted its brutality as a legacy of Judaism. In any event, Juan Aranzadi frequently denounced the policies of successive Israeli governments. He rejected Zionism as a political phenomenon based on an ethno-religious identity, just as despicable in his eyes as the racial nationalism of certain Basque political organizations, whether legal or terrorist.

The split between these two famous Basque intellectuals became irreconcilable, though both continued to display true political courage. It is striking, but in truth not altogether surprising, that their joint front in the fight against radical and violent nationalism should have fractured over the Jewish question. A question, as we know, that has haunted Spain since 1492 – both Spain as a whole and the Basque region of Spain specifically.

Since the 1970s, in any case, Spanish society has undergone very profound cultural, social, and political transformation. The only ones who feign not to see this are those commentators who, pining for exoticism, fill the columns of newspapers and magazines with articles on how Francoism persists beneath the surface of present-day Spanish life. Significant steps have been made in the intellectual and creative fields with regard to the Jewish question. Jon Juaristi’s conversion to Judaism may also be viewed as signaling a break with a Basque imaginary of purity, embedded in that of Spanish purification. Mention may also be made of Seharad (2001), by Antonio Muñoz Molina, a book that addresses anti-Semitism as a central legacy in European history – including in Spain – that was bequeathed by the Inquisition to Nazism and Stalinism60. This book blends genres, and provides a compendious overview enabling the Spanish reader to revisit and share in a common European awareness of the historical importance of the paths taken by anti-Semitism.

Conclusion: Basque nationalism as a radical form of Spanish nationalism

Thus the ethnic essentialism of Basque nationalism, including its racist dimension, was no exception in late modern Spain. Its argumentative mode, much like its appeals to an intellectual and institutional history stretching back to the sixteenth century, are virtually indistinguishable from pronouncements in the rest of the country. The socio-political processes that formed the Kingdom of Spain at the end of the Middle Ages gave birth to a system of religious and racial societal regulation. Catholic intransigence, attachment to ideas of blood purity, obsession with remaining faithful to the lineage, the code of honor – these were all features that fed into the assertion of Basque universal nobility, as well as Spanish casticismo more generally. The idea of the Basque country as a refuge of Old Christian purity only made sense because the New Christians were victims of segregation throughout Spain61. These two phenomena had been, in truth, perfectly harmonized as of the sixteenth century. The tragedy of Basque nationalism was that, from that point on, it was unable to distinguish itself from Spanish nationalism in general. We see the same prejudices, the same values, with both founded in the same historical conception of blood purity, and the same Catholic intransigence. This was a sibling rivalry between twins, perhaps even Siamese ones, spawned of the same reactionary bed.

Notes

1

Eva Larrauri, “Saizarbitoria en voz alta”, El Pais, Pais Vasco, June 17th 2011.

2

Gonzalo Álvarez Chillida, El antisemitismo en España: la imagen del judío, 1812-2002, Madrid, Marcial Pons, 2002, p. 238.

3

Ulrich Herbert, Werner Best. Un nazi de l'ombre (1903-1989), Paris, Tallandier, 2010, p. 290-293.

4

Santiago de Pablo and Teresa Sandoval, “Im Lande der Basken (1944). El País Vasco visto por el cine nazi”, Estudios Vascos, Sancho el Sabio, n° 29, 2008, p. 157-197.

5

Santiago de Pablo, Teresa Sandoval, “Im Lande der Basken (1944). El País Vasco visto por el cine nazi”, Estudios Vascos, Sancho el Sabio, n° 29, 2008, p. 157-197.

6

Juan Aranzadi, Jon Juaristi and Patxo Unzueta, Auto de terminación: (raza, nación y violencia en el País Vasco), Madrid, Aguilar-El País, 1993.

7

Juan Aranzadi, Jon Juaristi and Patxo Unzueta, Auto de terminación: (raza, nación y violencia en el País Vasco), Madrid, Aguilar-El País, 1993, p. 129.

8

Arzalluz : “if there is a true nation in Europe, ethnically speaking, it is Euskady”, El Pais, February 7th 1993.

9

Antonio Elorza, Tras la huella de Sabino Arana : los orígenes del nacionalismo vasco, Madrid, Temas de Hoy, 2005.

10

Sabino Arana, “Maketería y maketismo”, Bizkaitarra, February 2nd 1895.

11

Léon XIII, Quarto Abeunte Saeculo, Acta Santae Sedis, vol. XXV, Roma, 1892-93, p. 3-7.

12

José Alvarez Junco, Mater Dolorosa: la idea de España en el siglo XIX, Taurus, 2001, p. 269.

13

Sabino Arana, “Extranjerización”, El Correo Vasco, August 10th 1899.

14

Carlos Serrano Lacarra, “Conciencia de la crisis, conciencias en crisis”, in J. Pan-Montojo (ed), Más se perdió en Cuba. España, 1898 y la crisis de fin de siglo, Madrid, Alianza Editorial, 1998, p. 335-404.

15

Sabino Arana, “Nuestra voz”, Bizkaitarra, September 30th 1894.

16

Juan Aranzadi, El escudo de Arquíloco. Sobre mesías, mártires y terroristas, vol. 1 Sangre vasca, Madrid, A. Machado Libros, 2001, p. 230.

17

Luis de Eleizalde, Raza, lengua y nación vascas (A propósito de unos artículos publicados en el Debate de Madrid, por el Señor Don Fernando de Antón del Olmet, bajo el título El nacionalismo vasco y los orígenes de la raza vascongada), Bilbao, Eléxpuru Hermanos, 1911, p. 44.

18

Luis de Eleizalde, Raza, lengua y nación vascas (A propósito de unos artículos publicados en el Debate de Madrid, por el Señor Don Fernando de Antón del Olmet, bajo el título El nacionalismo vasco y los orígenes de la raza vascongada), Bilbao, Eléxpuru Hermanos, 1911, p. 41.

19

Luis de Eleizalde, Raza, lengua y nación vascas (A propósito de unos artículos publicados en el Debate de Madrid, por el Señor Don Fernando de Antón del Olmet, bajo el título El nacionalismo vasco y los orígenes de la raza vascongada), Bilbao, Eléxpuru Hermanos, 1911, p. 44-45.

20

Mariano Arigita y Lasa, Los Judíos en el País Vasco: su influencia social, religiosa y política, Pampelune, García, 1908, p. 21-22.

21

Mariano Arigita y Lasa, Los Judíos en el País Vasco : su influencia social, religiosa y política, Pamplona, García, 1908, p. 47.

22

George L. Mosse, Les Racines intellectuelles du Troisième Reich. La crise de l’idéologie allemande, Paris, Seuil, 2008, p. 165-193.

23

Mikel Azurmendi, Y se limpie aquella tierra. Limpieza étnica y de sangre en el Pais Vasco (siglos XVI-XVIII), Madrid, Taurus, 2000.

24

Juan Aranzadi, “Raza, linaje, familia y casa-solar en el Pais Vasco”, Hispania, 61-3, 2001, p. 879-906 ; José Maria Portillo Valdés, “Republica de hidalgos. Dimension política de la hidalguía universal entre Vizcaya y Guipúzcoa”, in José Ramón Díaz de Durana Ortiz de Urbina (ed.), La Lucha de bandos en el pais Vasco: de los Parientes Mayores a la Hidalguía Universal: Guipúzcoa, de los bandos a la provincia (siglos XIV a XVI), Bilbao, Universidad del País Vasco, 1998, p. 425-437.

25

Jon Arrieta, “Nobles, libres e iguales, pero mercaderes, ferrones... y frailes. En torno a la historiografía sobre la hidalguía universal”, Anuario de Historia del Derecho Español, LXXXIV, 2014, p. 799-842; Pablo Fernández Albaladejo and José María Portillo Valdés, “Hidalguía, fueros y constitución política: el caso de Guipúzcoa”, in Hidalgos & hidalguía dans l’Espagne des XVIe-XVIIIe siècles. Théories, pratiques et représentations, Paris, Editions du CNRS, 1989, p. 149-165.

26

Baltasar de Echave, Discursos de la antigüedad de la lengua cantabra bascongada, Mexico, Henrico Martinez, 1607, f. 66v.

27

Fuero Nuevo de Vizcaya (1526), Durango, Leopoldo Zugaza, 1976, p. 11.

28

Fuero Nuevo de Vizcaya (1526), Durango, Leopoldo Zugaza, 1976, p. 12-13.

30

Jon Arrieta, “El licenciado Andrés de Poza y su contribución a la ubicación de Vizcaya en la Monarquía hispánica », in J. Arrieta, X. Gil, J. Morales (éds)., La diadema del rey. Vizcaya, Navarra, Aragon y Cerdeña en la Monarquía de España, Bilbao, Universidad del Pais Vasco, 2017, p. 169-229.

31

Andres de Poza, De la antigua lengua, poblaciones, y comarcas de las Españas, Bilbao, Mathias Mares, 1587; Jon Juaristi, Vestigios de Babel. Para una arqueología de los nacionalismos españoles, Madrid, Siglo XXI, 1992.

32

Juan Martínez de Zaldivia, Suma de las cosas cantábricas y guipuzcoanas, Diputación Provincial de Guipúzcoa, 1944, p. 25-26.

33

Manuel de Larramendi, Corografia de la Provincia de Guipuzcoa (1754), Echévarri, Editorial Amigos del Libro Vasco, 1986, p. 140.

34

Manuel de Larramendi, Corografia de la Provincia de Guipuzcoa (1754), Echévarri, Editorial Amigos del Libro Vasco, 1986, p. 298.

35

Manuel de Larramendi, Corografia de la Provincia de Guipuzcoa (1754), Echévarri, Editorial Amigos del Libro Vasco, 1986, p. 157.

36

Pedro de Fontecha y Salazar, Escudo de la mas constate fe y lealtad (1749), Jon Arrieta Alberdi ed., Bilbao, Universidad del Pais Vasco, 2013, p. 826.

37

Coro Rubio Pobes, Revolución y tradición. El País Vasco ante la Revolución liberal y la construcción del Estado español, 1808-1868, Madrid, Siglo XXI, 1996.

38

Joshua Goode, Impurity of blood. Defining race in Spain, 1870-1930, Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Press, 2009, p. 28.

39

Francisco Pelayo López, Rodolfo Gonzalo Gutiérrez, Juan Vilanova y Piera (1821-1893), la obra de un naturalista y prehistoriador valenciano, Valence, Museo de Prehistoria de Valencia /Diputación de Valencia, 2012.

40

Joshua Goode, Impurity of blood. Defining race in Spain, 1870-1930, Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Press, 2009, p. 29.

41

Carlos Carrete Parrondo, Los judíos en la España contemporánea: historia y visiones, 1898-1998, Cuenca, Universidad de Castilla La Mancha, 2000; Danielle Rozenberg, L’Espagne contemporaine et la question juive: les fils renoués de la mémoire et de l’histoire, Toulouse, Presses du Mirail, 2006; Javier Domínguez Arribas, El enemigo judeo-masónico en la propaganda franquista, 1936-1945, Madrid, Marcial Pons, 2009.

42

Salvador Cayuela Sánchez, “Biopolítica, nazismo, franquismo. Una aproximación comparativa”, Éndoxa. Series Filosóficas, 28, 2011, p. 257-286.

43

Enrique Gonzalez Duro, Los psiquiatras de Franco: Los rojos no estaban locos, Barcelona, Peninsula, 2008, p. 45-14; Alfredo Jesús Sosa-Velasco, Médicos escritores en España, 1885-1955. Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Pío Baroja, Gregorio Marañón y Antonio Vallejo Nágera, Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK; Rochester, NY, Tamesis, 2010.

44

Antonio Vallejo Nágera, “Maran-atha”, Divagaciones intrascendentes, Valladolid, Talleres Tipográficos Cuesta, 1938, p. 95-98.

45

Quoted by José María Ruíz-Vargas, “Trauma y memoria de la Guerra Civil y la dictadura franquista”, in J. Aróstegui Sánchez, S. Gálvez Biesca (éds), Generaciones y memoria de la represión franquista: un balance de los movimientos por la memoria, Valence, Universitat de València, 2010, p. 157.

46

Arriba, May, 20th of1939.

47

Luis Mariano González González, Fascismo, kitsch y cine histórico español (1939-1953), Cuenca, Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, 2009, p. 47-67.

48

Jon Juaristi, El linaje de Aitor, Madrid, Taurus, 1998.

49

Claude Singer, Le Juif Süss et la propagande nazie. L'histoire confisquée, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 2003.

50

Alberto J. Lleonart y Amsélem, España y ONU: estudios introductivos y corpus documental. (1952-1955), vol. 6, Madrid, Editorial CSIC, 1978, p. 23-61.

51

Henri Lapeyre, “Deux interprétations de l’histoire d’Espagne : Américo Castro et Claudio Sánchez Albornoz”, Annales. Économies, Sociétés, Civilisations, 20-5, 1965, p. 1015-1037.

52

Claudio Sánchez-Albornoz, España un enigma histórico, Barcelona, Edhasa, 1973, p. 241.

53

Claudio Sánchez-Albornoz, España un enigma histórico, Barcelona, Edhasa, 1973, p. 297.

54

Danielle Rozenberg, “L’État et les minorités religieuses en Espagne (du national-catholicisme à la construction démocratique)”, Archives des sciences sociales des religions, 98, 1997, p. 9-30.

55

Alejandro Baer, “The voids of Sepharad: the memory of the Holocaust in Spain”, Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies, vol. 12, n° 1, 2011, p. 95-120.

56

Javier Cercas, The Impostor, London, Quercus, 2017.

57

Xavier Casals, “La ultraderecha española: una presencia ausente (1975-1999)”, Historia y política, n° 3, p. 147-171.

58

El Pais, January the 20th of 1979.

59

Paul Preston “Una contribución catalana al mito del contubernio judeo-masónico-bolchevique”, in J. Aróstegui Sánchez, S. Gálvez Biesca eds, Generaciones y memoria de la represión franquista: un balance de los movimientos por la memoria, Valence, Universitat de València, 2010, p. 259-272; Danielle Rozenberg, L’Espagne contemporaine et la question juive: les fils renoués de la mémoire et de l’histoire, Toulouse, Presses du Mirail, 2006, p. 82-84.

60

Antonio Muñoz Molina, Séfarade, Paris, Le Seuil, 2003.

61

Christiane Stallaert, Etnogénesis y etnicidad en España. Una aproximación histórico-antropológica al casticismo, Barcelone, Proyecto A Ediciones, 1998, p. 70-76.

Bibliographie

Fuero Nuevo de Vizcaya [1526], Durango, Leopoldo Zugaza, 1976.

Gonzalo Álvarez Chillida, El antisemitismo en España: la imagen del judío, 1812-2002, Madrid, Marcial Pons, 2002.

José Álvarez Junco, Mater Dolorosa: la idea de España en el siglo XIX, Taurus, 2001.

Sabino Arana, “Nuestra voz”, Bizkaitarra, September 30th 1894.

Sabino Arana, “Maketería y maketismo”, Bizkaitarra, February 2nd 1895.

Sabino Arana, « Extranjerización », El Correo Vasco, August 10th 1899.

Juan Aranzadi, Jon Juaristi, Patxo Unzueta, Auto de terminación: raza, nación y violencia en el País Vasco, Madrid, Aguilar-El País, 1993.

Juan Aranzadi, El escudo de Arquíloco. Sobre mesías, mártires y terroristas, vol. 1 Sangre vasca, Madrid, A. Machado Libros, 2001.

Mariano Arigita y Lasa, Los Judíos en el País Vasco: su influencia social, religiosa y política, Pampelune, García, 1908.

Jon Arrieta, “Nobles, libres e iguales, pero mercaderes, ferrones... y frailes. En torno a la historiografía sobre la hidalguía universal”, Anuario de Historia del Derecho Español, LXXXIV, 2014, p. 799-842.

Jon Arrieta, “El licenciado Andrés de Poza y su contribución a la ubicación de Vizcaya en la Monarquia hispánica”, in J. Arrieta, X. Gil, J. Morales (dir.), La diadema del rey. Vizcaya, Navarra, Aragon y Cerdeña en la Monarquia de España, Bilbao, Universidad del Pais Vasco, 2017, p. 169-229.

Mikel Azurmendi, Y se limpie aquella tierra. Limpieza étnica y de sangre en el Pais Vasco (siglos XVI-XVIII), Madrid, Taurus, 2000.

Alejandro Baer, “The voids of Sepharad: the memory of the Holocaust in Spain”, Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies, vol. 12, n° 1, 2011, p. 95-120.

Carlos Carrete Parrondo, Los judíos en la España contemporánea historia y visiones, 1898-1998, Cuenca, Universidad de Castilla La Mancha, 2000.

Xavier Casals, “La ultraderecha española: una presencia ausente (1975-1999)”, Historia y política, n° 3, 2000, p. 147-171.

Salvador Cayuela Sánchez, “Biopolítica, nazismo, franquismo. Una aproximación comparativa”, Éndoxa. Series Filosóficas, n° 28, 2011, p. 257-286.

Javier Cercas, The Impostor, London, Quercus, 2017.

Javier Domínguez Arribas, El enemigo judeo-masónico en la propaganda franquista, 1936-1945, Madrid, Marcial Pons, 2009.

Baltasar de Echave, Discursos de la antigüedad de la lengua cantabra bascongada, Mexico, Henrico Martinez, 1607.

Luis de Eleizalde, Raza, lengua y nación vascas, Bilbao, Eléxpuru Hermanos, 1911.

Antonio Elorza, Tras la huella de Sabino Arana : los orígenes del nacionalismo vasco, Madrid, Temas de Hoy, 2005.

Pablo Fernández Albaladejo, José María Portillo Valdés, “Hidalguía, fueros y constitución política: el caso de Guipúzcoa”, in Hidalgos & hidalguía dans l’Espagne des XVIe-XVIIIe siècles. Théories, pratiques et représentations, Paris, Éditions du CNRS, 1989, p. 149-165.

Pedro de Fontecha y Salazar, Escudo de la mas constate fe y lealtad [1749], Bilbao, Universidad del Pais Vasco, 2013.

Enrique González Duro, Los psiquiatras de Franco: Los rojos no estaban locos, Barcelone, Peninsula, 2008.

Luis Mariano González González, Fascismo, kitsch y cine histórico español (1939-1953), Cuenca, Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, 2009.

Joshua Goode, Impurity of blood. Defining Race in Spain, 1870-1930, Baton Rouge, Louisiana State University Press, 2009.

Ulrich Herbert, Werner Best. Un nazi de l'ombre (1903-1989), Paris, Tallandier, 2010.

Jon Juaristi, Vestigios de Babel. Para una arqueología de los nacionalismos españoles, Madrid, Siglo XXI, 1992.

Jon Juaristi, El linaje de Aitor, Madrid, Taurus, 1998.

Henri Lapeyre, “Deux interprétations de l'histoire d'Espagne: Américo Castro et Claudio Sánchez Albornoz”, Annales. Économies, Sociétés, Civilisations, vol. 20, n° 5, 1965, p. 1015-1037.

Manuel de Larramendi, Corografia de la Provincia de Guipuzcoa [1754], Echévarri, Editorial Amigos del Libro Vasco, 1986.

Alberto J. Lleonart and Amsélem, España y ONU: estudios introductivos y corpus documental. (1952-1955), vol. 6, Madrid, Editorial CSIC, 1978.

Juan Martínez de Zaldivia, Suma de las cosas cantábricas y guipuzcoanas, Diputación Provincial de Guipúzcoa, 1944.

George L. Mosse, Les Racines intellectuelles du Troisième Reich. La crise de l’idéologie allemande, Paris, Le Seuil, 2008.

Antonio Muñoz Molina, Séfarade, Paris, Le Seuil, 2003.

Santiago de Pablo and Teresa Sandoval, “Im Lande der Basken (1944). El País Vasco visto por el cine nazi”, Estudios Vascos, Sancho el Sabio, n° 29, 2008, p. 157-197.

Francisco Pelayo López and Rodolfo Gonzalo Gutiérrez, Juan Vilanova y Piera (1821-1893), la obra de un naturalista y prehistoriador valenciano, Valence, Museo de Prehistoria de Valencia /Diputación de Valencia, 2012.

José Maria Portillo Valdés, “Republica de hidalgos. Dimension política de la hidalguía universal entre Vizcaya y Guipúzcoa”, in J. Ramón Díaz de Durana Ortiz de Urbina (ed.), La Lucha de bandos en el pais Vasco: de los Parientes Mayores a la Hidalguía Universal : Guipúzcoa, de los bandos a la provincia (siglos XIV a XVI), Bilbao, Universidad del País Vasco, 1998, p. 425-437.

Andres de Poza, De la antigua lengua, poblaciones, y comarcas de las Españas, Bilbao, Mathias Mares, 1587.

Paul Preston, “Una contribución catalana al mito del contubernio judeo-masónico-bolchevique”, in J. Aróstegui Sánchez, S. Gálvez Biesca (dir.), Generaciones y memoria de la represión franquista: un balance de los movimientos por la memoria, Valencia, Universitat de València, 2010, p. 259-272.

José María Ruíz-Vargas, “Trauma y memoria de la Guerra Civil y la dictadura franquista”, in J. Aróstegui Sánchez, S. Gálvez Biesca (dir.), Generaciones y memoria de la represión franquista: un balance de los movimientos por la memoria, Valence, Universitat de València, 2010.

Coro Rubio Pobes, Revolución y tradición. El País Vasco ante la Revolución liberal y la construcción del Estado español, 1808-1868, Madrid, Siglo XXI, 1996.

Danielle Rozenberg, “L’État et les minorités religieuses en Espagne (du national-catholicisme à la construction démocratique)”, Archives des sciences sociales des religions, n° 98, 1997, p. 9-30.

Danielle Rozenberg, L'Espagne contemporaine et la question juive: les fils renoués de la mémoire et de l’histoire, Toulouse, Presses du Mirail, 2006.

Claudio Sánchez-Albornoz, España un enigma histórico, Barcelona, Edhasa, 1973, p. 241.

Carlos Serrano Lacarra, “Conciencia de la crisis, conciencias en crisis”, in J. Pan-Montojo (ed), Más se perdió en Cuba. España, 1898 y la crisis de fin de siglo, Madrid, Alianza Editorial, 1998, p. 335-404.

Claude Singer, Le Juif Süss et la propagande nazie. L'histoire confisquée, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 2003.

Alfredo Jesús Sosa-Velasco, Médicos escritores en España, 1885-1955. Santiago Ramón y Cajal, Pío Baroja, Gregorio Marañón y Antonio Vallejo Nágera, Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK, Rochester, NY, Tamesis, 2010.

Christiane Stallaert, Etnogénesis y etnicidad en España. Una aproximación histórico-antropológica al casticismo, Barcelone, Proyecto A Ediciones, 1998, p. 70-76.

Antonio Vallejo Nágera, “Maran-atha”, Divagaciones intrascendentes, Valladolid, Talleres Tipográficos Cuesta, 1938, p. 95-98.