(The American University of Paris (AUP) - Department of Communication, Media and Culture)

The utopic perspective that guides our contribution encourages experimentation1. Therefore, like the tasting practice we examine, this contribution is a hybrid. This requires risk-taking on our part, but also on yours. We all share certain understandings about what academic texts should include. We also know, however, that power is entangled in this process, shaping our assumptions about what can be said and received.

A reflexive approach encourages us to actively consider how power works through us. The end-goal is to free ourselves from power long enough to think and act differently. For this reason, we believe that socio-sensory reflexivity is essential for utopic practice. Our interlocutors taste, as we research and write, in a reflexive manner. For the circle to be complete, we ask that you too, the reader, do the same2.

We also experiment here with form. Therefore, while this text reads like other scholarly works—there is an introduction, literature review, methodological discussion, analysis and conclusion—it also diverges from traditional academic conventions. It is, for example, elaborated through a cooperative process involving professor and undergraduate students who have only just encountered sensory and ethnographic methodologies. It is also multimodal: integrating photos and a student film alongside the central text. These contributions represent a patchwork of experiences and relationships that span time and space. With this multi-modal play we hope to thicken our description by evoking not only our positionalities, but also aspects of our experiences and those of our interlocutors that transcend the text proper yet resonate with the jury terroir’s cooperative practice and its utopic process.

Our main analytical point is this: the conventional view sees taste primarily as a marker of social distinction. From this perspective, tasting practices merely reproduce existing hierarchies rather than create change. In this article, we propose another model of taste. Cooperative taste is a tactical practice characterized by egalitarian exchange and thick description, with the explicit political aim of resisting standardization, that renders an old, yet new food imaginary possible through shared embodied and affective experience.

We draw this model from ethnographic research with the jury terroir, a sensory panel consisting of Comté cheese producers and regional inhabitants who meet several times a year to describe the tastes of Comté cheeses. Founded in the early 1990s, the jury terroir is a hybrid practice, first developed in response to industry pressures to standardize tastes and rationalize production. The jury develops a new practice and vocabulary for articulating and valuing the gusto-olfactive diversity that characterizes Comté production. In so doing, it plays a key role in maintaining the web of farmer cooperatives, or fruitières, at the heart of the production model.

In this article, we focus on the jury terroir’s early years. Florence Bérodier, the food scientist who developed the jury terroir, refers to members of the early jury as ‘trailblazers’ (défricheurs). This group set out to invent and then experiment with a new tasting practice to see if Comté could be reimagined as a terroir product, a notion both they and chain3 members found inconceivable at the time. They render the unimaginable imaginable; in so doing, they invent a unique cooperative tasting practice and an interpretation of terroir that articulates diversity (alongside typicity). Wilder defines utopia as “thought or action oriented toward that which appears to be, or is purported to be impossible when such impossibility is only the function of existing arrangements”4. We contend that cooperative tasting as elaborated by the jury terroir is a utopic practice.

Central to our analysis is the jury’s practice of mise en commun (placing in a commons) of sensory perceptions. Mise en commun is used locally to refer to the pooling together of farmers’ milk to make Comté cheese each morning as well as the organization of collective discussions within cooperative meetings. When used in the jury terroir, the mise en commun organizes the sharing of sensory perceptions, particularly the aromatic descriptors we focus on in this paper. Importing the mise en commun into the jury terroir introduces cooperation as an organizing framework within their tasting practice.

While our analysis is focused on the mise en commun we also tend, with more impressionistic strokes, to the wider historical evolution of taste within the Comté chain. This approach is inspired by the work of two scholars: first, economic anthropologist Gibson-Graham calls for a “new performative ontology” characterized by “thick description and weak theory” in order to bring solidarity economies into view5; and second, cultural studies scholar Ben Highmore argues that to see taste as “an agent that orchestrates and transforms sensibilities” we need to foster a new “kind of aesthetic form”, one that treats tastes as an endless series of micro-practices and an unfolding evolution of macro-practices6. To return to our experimental approach: capturing the transformational power of taste in the manner suggested by these scholars, and doing justice to the jury terroir’s story, has required us to expand beyond conventional article length, embracing the time and space needed for thick description to reveal its full potential.

In what follows we briefly introduce our utopic perspective and methodology as well as Comté cheese and the challenges it faced at the turn of the century. Then, we examine cooperative tasting as tactical, egalitarian, descriptive, embodied and felt. In a final analysis, we return to our utopic perspective to explore how cooperative taste creates both concrete interventions in institutional structures and resonant spaces that extend beyond immediate contexts.

A utopic perspective

By utopia, we do not suggest some lofty ideal that cannot exist in the real world. Instead, we refer to the imaginative and convivial use of everyday sensory and social practices that give rise to a differential consciousness – an awareness that allows us to acknowledge and survive disempowering structures while generating alternative beliefs and tactics that resist domination7. We argue that the jury terroir ignites such a process in the 1990s, acting as an “incubation space” where the experimental and imaginative use of local practices and experiences make “new configurations of people and things possible”8 through sensory perception.

Our utopic perspective brings the cooperative into view. A cooperative is an organization owned and run jointly by its members, who share in labor and profits. Cooperatives share key features: voluntary membership, democratic control (one person, one vote), operational autonomy, ongoing education, and care for the wider community9. While maintaining some hierarchical structures, cooperatives prioritize egalitarian participation and solidarity. Despite mixed success in achieving their ideals, they remain an important bulwark against the excesses of industrial capitalism. Comté's fruitière system is part of a rich history of cooperation in the Franche-Comté region (France) that includes utopic thinkers like Charles Fournier and a range of “solidarity forms”, both past and present10.

While the cooperative is key to this story, our analysis focuses on the tasting practices of the jury terroir. Our perspective is therefore informed by the social science literature devoted to food and the senses. Like cooking or eating together, tasting can be understood as a system of communication11. The senses are our first media, the conduit through which we perceive, make sense of, and act within the world12.

A wide range of critical studies has demonstrated how our tastes are interwoven with global, industrial food systems—how our taste for sweetness is shaped by the global political economy13, or how taste for luxury or necessity normalizes social hierarchies14. By standardizing tastes, the modern food system disembeds us from place and disturbs our sense of self15. This critical literature is vital in understanding how power structures our senses. However, when taken too far or applied too dogmatically, this literature can leave us feeling that change or resistance to these systems would be naïve and futile.

We draw here from contemporary scholars who reimagine taste as a means toward emancipation. They highlight the co-constructive nature of taste practices that form attachments between things and people16, the practice of sensory intersubjectivity17, tasting as integral to place-making18 and the taste of place19, or the entanglement of the senses, memory and affect in ritual process20.

Our encounter with the jury terroir invites reflection on the interconnections among cooperatives, sensory perception, and utopic intentions in ways rarely explored in the literature. Charles Fourier (1772-1837), a Franche-Comté native, drew inspiration from the fruitière for his “gastrophilosophy,” envisioning Harmony—a social order where food functions as a “total social phenomenon”21. Fourier and fellow utopians (like Victor Considerant) believed that “a more just society must be built from a small basic unit [...] reconstructed from below”22. While not claiming our case represents Fourier’s Harmony, we suggest that his emphasis on sensory development, the fruitière as a ‘basic cell’, and bottom-up utopian practice resonates with our story.

An experimental methodology

Our methodology, like the jury terroir itself, can be understood as an experimental, hybrid practice. It builds on traditional ethnographic protocols through long-term research carried out over fifteen years using observational, sensory, interviewing and writing techniques embedded within dialogical exchange. Yet it diverges through its unique ‘cooperative’ nature – beginning not with a solitary research trip but with a cooperatively-designed pedagogical experiment involving sensory ethnographer (author Shields-Argelès) and sensory educator and jury terroir member (Claire Perrot), funded through small research grants rather than major foundations.

This research has been carried out tactically, in available moments: during the study trips mentioned above, on weekends, within family vacations23. It therefore involves, from the onset, students testing ethnographic methods for their first time as a means for understanding themselves and others through encounters with difference. Like the home cook described by Luce Giard, this approach weaves connections through embodied and multisensory practices embedded in orchestrated, nourishing events24.

The present article and its accompanying film draw particularly from a two-week field study conducted in June 2024 by its authors: professor Christy Shields-Argelès and students Eliza Schwartz and Annika Lovgren. Our immersive approach encompassed four key dimensions:

From left to right: Montbéliard cows (© Eliza Schwartz); Lovgren at the fruitière (© Christy Shields-Argelès); visit to an aging cellar (© Annika Lovgren); visit with the jury terroir (© Eliza Schwartz).

First, we engaged with all three stages of the Comté production chain—visiting farms, fruitières, and affineurs—while attending to the sensory environment at each stage. Second, we participated in a jury terroir meeting, experiencing firsthand the process of identifying aromatic descriptors. Third, we extended our research beyond the Comté chain to engage with local artists, artisans (wine makers, potters), and collectives (L’Entrepôt), in order to get a sense of other artisanal and solidarity-focused practices in the region. Finally, we participated in shared meals, tastings, market visits, and nature walks with interlocutors and friends—experiences that highlight the intricate relationships among local products, landscapes, and people.

From left to right: Shields-Argelès and Lovgren filming insects in a pasture (© Eliza Schwartz); visit with winemaker Jean-Mi (© Christy Shields-Argelès); a visit to the ‘Entrepôt’ with Claire Perrot (© Eliza Schwartz); Shields-Argelès and Bérodier in conversation (© Eliza Schwartz).

Throughout this process, we cultivated what Dara Culhane terms “sensory embodied reflexivity”25. This approach operates on three levels: multisensory (fostering mindful attention to all senses and their interactions), embodied (treating the body as both research tool and social agent, recognizing its entanglement with other humans and nonhumans in shared environments), and affective (understanding emotion as both individual and collective, constituted by interconnected movements of feelings circulating among emplaced beings in particular times and places).

Ultimately, our methodology aimed to transcend individual experience to become itself a shared, collective, cooperative endeavor—reflecting and embodying the very practices we sought to understand.

Comté cheese: Cooperation, Diversity, and Response to Industry Pressures

This section examines how the Comté cheese supply chain maintained its distinctive character while adapting to market pressures at the turn of the last century.

Comté cheese: Gusto-Olfactive Diversity and the Cooperative System

Comté cheese is a raw milk cheese produced in eastern France, along the Jura mountain range. Today, Comté is widely recognized as a model PDO (Product of Designated Origin)26. What is often overlooked in Comté’s success is the gusto-olfactive diversity that characterizes Comté production, and its imbrication with the chain’s cooperative structure. Tastes vary according to age, season, savoir-faire and terroir. Cheeses vary in physical appearance, texture, and even sound. They can be more or less salty, acidic, bitter, sweet or umami. They also offer diverse smells, both in terms of odeurs (olfaction) and arômes (retro-olfaction).

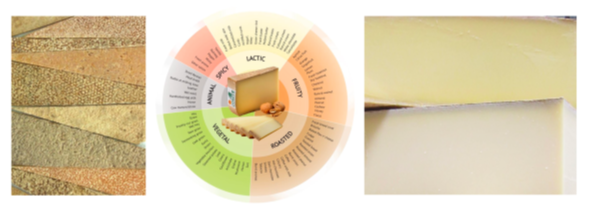

From left to right: Comté cheese crusts (© Claire Perrot); the Comté Aroma Wheel in English (© CIGC); Comté cheeses displayed on market stall (© Shields-Argelès).

This diversity is interwoven with production through the fruitières, or cooperative cheese dairies owned and run by their farmer-members. Today 2400 dairy farmers are organized into 140 fruitières. Farms must be located within a 25-kilometer diameter of their fruitière, meaning that the milk contributed represents a distinct terroir. Farmers hire cheesemakers to transform their milk into wheels of Comté every morning and work with regional aging facilities to bring their cheese to maturity and market27.

Prior to the 1980s, Comté’s gusto-olfactive diversity required little sustained attention. A retired farmer expressed it this way:

“We’d say ‘it’s good’ or ‘it’s not good’. (...) I liked the Comté of Villers, and the people of Villers didn’t like the Comté of Arc because.... well, because it was from Arc! (...) We only liked the one we produced”.

Challenges to Diversity: The Emergence of the Jury Terroir

In the 1980s, Comté’s gusto-olfactive diversity was recast as a liability. Jean-Jacques Bret, Director of the Comité interprofessionnel de gestion du Comté (CIGC) from 1983 to 201328, explains:

“Comté was considered unsuitable for the consumer world. (...) At the time, the experts were saying that the future belonged to traditional products, but consistent in taste.”

For Bret and others, this seemed a “paradoxical diagnostic”. He adds:

“At the time, there was an expression in the industrial dairy sector, including AOC [i.e. PDO], which was: ‘All milk is white’. This meant that milk is only a raw material. (...) An ideological statement, no doubt sincere.”

These experts identified the fruitière system as the main culprit, and suggested replacing it with two to three factories. This, they argued, would allow Comté to increase production volumes, oversee quality control and standardize tastes. Of course, it would also deprive farmers of ownership and control over production, and villages of an important socio-economic institution.

Florence Bérodier remembers encountering these challenges through a conversation with Yves Goguely, Comté milk producer and CIGC president from 1987 to 2002. The regional council had asked local producers to present their products. Goguely presented three different Comté cheeses but returned from the meeting feeling humiliated. Bérodier recalls his face was red as he twisted a paper clip until it broke; he said:

“We didn't have anything to say! You do as you please, but make sure we can talk about our product! [...] Afterall, we have a product with qualities too. We have different tastes”.

A terroir model thus emerged as a potential solution, promising to articulate the value of the fruitières and Comté’s gusto-olfactive diversity by linking place, production and taste. In 1990, the CIGC enlisted Jacques Puisais, a well-known oenologist who championed terroir during these years. Puisais and his team offered initial lists of descriptors and suggested they form a “jury terroir” of regional inhabitants and chain members, to reappropriate their descriptive tasting practice and its vocabulary, establishing it thus as a potential site for empowerment. Bérodier remembers him suggesting to her, for example, to integrate as many farmers and as few technicians as possible. In other words, the jury terroir was to train and then integrate the perceptions of those who rarely participated in such instances of power.

However, there was a problem, and an important one: no one in the chain, let alone the jury terroir, felt terroir had anything to do with their cheese. As one early panelist recalled from Puisais’ initial training:

“I remember when Mr. Puisais arrived and said ‘in your Comté we can find this and that’, I said to myself, ‘this is nonsense!’”

Beyond the initial skepticism, Bérodier faced challenges in establishing the jury terroir as a legitimate practice within an already charged sensory field with established power dynamics. Various actors already had tasting authority: technicians identified defects, agers guided maturation decisions, and an INAO-required panel evaluated typicity for labeling. The jury terroir emerged within this context, with Bérodier aware that proposing a new tasting practice could provoke suspicion among already-pressured cooperatives. She also navigated the power dynamics inherent in tasting protocols themselves, which can inadvertently reproduce social hierarchies or normalize industrial standards29. Because she imagined her work as applied science in service of farmers, she continuously evaluated and adjusted which protocols worked best for participants.

The Jury Terroir and its Mise en Commun: En Bref

Florence Bérodier formed the first jury terroir in 1990, developing this hybrid practice through trial and error with early “trailblazers”. The jury operated under her guidance until 2020, evolving throughout her thirty-year tenure, and continues today under new leadership.

The jury consists of a diverse array of volunteer tasters from the region and Comté chain, including farmers, cheese technicians, cellar masters, cheese mongers, food and wine enthusiasts, and culinary professionals from the local culinary and hospitality school. While there is no data concerning age or gender, we note from interviews and photos that early panelists were generally at the onset of their careers, though a few senior panelists played an important guiding role. The panel consists of both men and women, with a slight numerical advantage for the former in the early years. Typically, about eighteen trained panelists are available (with ten to twelve attending each session), and participation remained remarkably stable—by 2009, 55% were original members from 199030.

Importantly, the jury has always served a dual function. They produce scientific knowledge while fulfilling an important pedagogical mission. From 1990-2009, Bérodier trained 45 individuals in the tasting method. This educational dimension shaped both the jury’s open recruitment policy and its format. Bérodier aimed to maintain a rigorous practice while creating a welcoming space. Panelists often note that participation requires openness and curiosity, which certainly induces a certain self-selection. Newcomers participate in all aspects of a given session, but only contribute to the mise en commun when ready. Similarly, their tasting sheets are integrated into statistical analysis only after sufficient training.

The jury’s work appears in various scientific publications, notably the Comté Aroma Wheel—the first of its kind for artisanal cheese—and the fruitière ‘aroma palettes’ developed through the Terroir Programme, which linked sensory profiles with soil maps, climate assessments, and plant inventories to scientifically support the concept of terroir in Comté31. Today, these ‘aroma palettes’ continue to appear in the chain’s bi-monthly newsletter alongside descriptions and images recounting each fruitière’s social life.

As for the jury proper, it is organized into two main phases. A typical 2.5-hour session begins with the “mise en condition”—training exercises for attuning senses and training novices. Panelists then evaluate three to four Comté cheeses anonymously at 15-17°C, individually completing detailed evaluation sheets covering appearance, texture, odeurs, saveurs, and arômes.

The mise en commun operates at multiple levels. For Bérodier, it really begins during the individual tasting, which is structured to guide perception while allowing personal expression. For aromatic descriptors, tasters check boxes for aroma families and specific descriptors (with a space to include ‘other’ descriptors not listed). They then write down three to four primary descriptors as their “aromatic synthesis” and write out a description of the “image left by this Comté”.

After individual assessment, panelists share their perceptions. Sharing for visual aspect, texture, odeurs and saveurs happens in a rather informal way. However, exchange concerning aromatic descriptors is highly structured and ruled. Participants refer to this exchange as the mise en commun. Each participant shares their 3 to 4 descriptors in turn in a tour de table, followed by discussion moderated by Bérodier32. Importantly, the final synthesis—or sensory profile of a single fruitière’s cheese—is produced through statistical analysis carried out by Bérodier who works from the tasting sheets from 6 to 12 samples, generally between 8 and 18 months of age, from the same fruitière over a 3 to 4 year period (accounting for variation in season, age and other contextual variables)33.

Cooperative Taste is…

Tactical

The mise en commun is a key element of the jury’s hybridity. Its inclusion is a tactical move34 that brings everyday cooperative practice into the jury structure. Comté farmers use this term for pooling milk for cheesemaking—the chain’s foundational act of solidarity. Historically, farmers, with few cows, pooled milk to make large cheese wheels that would last the winter. Today, they continue this practice to counter global market forces. Chain members also use mise en commun for debates in fruitières’ cooperative meetings and CIGC commission meetings.

From left to right: The cheesemaker senses the right moment to gather the curd (© Jean-Claude Uzzeni); farmers pooling their milk together at the fruitière in Champagnole in 1901 (© Antoine Bérodier).

Of course, the mise en commun as used in the jury terroir is fundamentally different from those practiced elsewhere in the chain. In particular, the jury terroir does not have any decisional power. Indeed, as we saw above, their collective discussions do not produce the final synthesis proper.

And yet the mise en commun of aromatic descriptors is also similar to others in the chain. For example, in the jury, too, the mise en commun is a practice that assumes a diversity of perceptions as a starting point. As in cooperative meetings, it also consists of a structured tour de table and a moderated collective discussion. Ideally, this all takes place at an open table organized in a round.

From left to right: photos of tasting cubicles and Florence Bérodier in the early 1990s (© Florence Bérodier); the jury terroir in 2018 (© Thierry Petit).

These seemingly minor organizational aspects of the jury’s tasting practice represent thoughtful adaptations of standard sensory protocols. The mise en commun is introduced in between the individual tasting and statistical analysis of traditional protocol. Bérodier initially tried working in cubicles, per sensory protocol, but moved to an open format so participants could “taste alone first and then exchange and discuss”. In addition, even if panelists recognize that Bérodier calculates the final published synthesis, the mise en commun nonetheless renders the work of intersubjective attunement “public”35, opening up the process to both confirmed taster and novice alike. One jury member who experienced both cubical and open table approaches explained:

“When we worked in individual boxes, we would fill out the sheet, go see the moderator, and he compared 4 or 5 sheets saying ‘you found this, the others found this’, but the others weren’t there necessarily (...). With the jury terroir there is a real work. We are not in boxes but around a table, we circulate the cheeses, we describe them individually and discuss each one. There is an exchange, there is something shared, and a synthesis”.

In short, in rendering the ‘work’ of synthesis public, the mise en commun recognizes the jury’s syntheses as forms of power—not productive power (like making cheese) or decisional power (like voting on specifications), but representational power. This resonates with what Bret told Shields-Argelès about being an actor (acteur):

“When there was the mad cow crisis, we saw farmers interviewed on TV that were crushed by the system... When you interview a guy here, the difference is impressive. These people are actors. (...) They are actors because they define the production rules, they run their fruitières (...) They are actors in the identity they give to their product”.

Paradoxically, the jury’s work is also tactical because its practice is never generalized throughout the chain, and the jury’s representations (like the aroma palettes) rarely circulate outside of the chain or the region. The fruitière remains largely out of view to consumers outside the region, who interface uniquely with the aging houses. We will reflect upon such paradoxes later in the paper.

Egalitarian

An important component of the jury’s tactical nature relates to the egalitarian aspirations embedded in mise en commun. While egalitarianism holds that all people deserve equal treatment, anthropologists recognize that power differentials persist and require constant negotiation36. In this section, we examine the jury’s negotiated egalitarianism, which works against ranking reflexes and social hierarchies that typically dominate taste practices.

Following Urfalino37, we understand mise en commun as a form of deliberative democracy aiming for consensus through discussion. While this approach ensures minority viewpoints are considered, those with strong personalities or perceived expertise may influence the final consensus. The jury terroir brings together participants from different professional backgrounds, inevitably reflecting existing social stratification. As moderator, Bérodier herself shapes interactions and calculates final syntheses, sometimes struggling to moderate sessions involving authority figures whose presence influences others’ participation. Professional expertise occasionally surfaces, as when Shields-Argelès observed a cheese technician use a technical word instead of descriptive term during a mise en commun. We should therefore avoid romanticizing the mise en commun, even within the wider chain, interlocutors have noted fierce disagreements and strategic uses of the tour de table.

Nevertheless, the mise en commun structures sharing so each person’s perception receives “equal footing” (Bérodier). The strict silence during tasting and the three-to-four-descriptors-only rule ensures each intervention consists of the same descriptive vocabulary and equal length. The jury also employs leveling mechanisms—joking and gentle derision—that can work to prevent status differences from hardening into dominance. When the technician used a technical term in the above example, the jury responded with exaggerated “ooooooohs”, while a farmer exclaimed “there goes the technician!” Such exchanges both reflect and defuse social differentiation linked to sensory skills while reminding us that cooperation requires negotiation38.

Negotiated egalitarianism appears in the jury’s difficulty finding appropriate terminology for their role. Bérodier and jury members explicitly reject “connoisseur” as a label. When Shields-Argelès inadvertently used this term, she was quickly corrected. They prefer “amateur”, signaling their role as enthusiasts engaged in co-constructive practices39. Being “open” to others’ sensory worlds is crucial for jury members. Yet because jury members perform important sensory labor with long-term political implications beyond leisure activity, “amateur” never fit quite right, nor was it necessarily understood outside the jury.

We propose thinking of panelists as “cooperators” who import collaborative practices from the wider chain into the jury. Drawing from Illich, we conceptualize active listening and mutual respect as “tools for cooperation”—social practices that enable meaningful collaboration while respecting individual autonomy. These tools for cooperation build upon Illich’s notion of “tools for conviviality”, which he defines as facilitating “autonomous and creative intercourse among persons and the intercourse of persons with their environment”40. While conviviality might suggest mere friendliness or leisure, Illich’s concept—and our extension of it—carries explicitly political dimensions. In this way, tools for cooperation function as political instruments, resonating with Matta’s application of Illich’s conviviality in this volume, where such tools enable “holistic and interdisciplinary approaches addressing the interrelationship between culture, nature, politics, and the economy”41. In the jury terroir, active listening and mutual respect represent essential social skills that, alongside sensory skills, create spaces where individuals from various backgrounds can participate equitably in co-creating sensory knowledge and representations. A further analysis could identify additional social skills that function as tools for cooperation within this context, including an ethic of solidarity, referenced by more than one interlocutor among them.

This term “cooperator” emerged unexpectedly when a retired cooperative president described the cooperative as a “school of democracy” with the mise en commun as its most powerful socialization tool. Through this practice, newcomers learn collective decision-making and recognize shared responsibility. As the president noted, this experience “changed their way of interacting”—“instead of yelling, they began to listen to others and then to respect the other person’s speech, not interrupting them”. Interlocutors regularly identify active listening and mutual respect as central to meaningful collaboration, linking these modes to solidarity and creative solutions.

Within the jury terroir, these convivial practices are equally emphasized. After the cooperative president mentioned this, his wife, an early jury member, added, “it was the same in the jury terroir”. Bérodier identified listening and respect as vital, especially during the jury’s formative years as panelists developed tasting abilities by listening to one another. She consistently emphasized the importance of listening to new recruits:

“Each person has their own food culture and their ability to find certain words more easily than others (...) afterward we each learn to take on a larger part of each other’s puzzle and the zones of overlap increase. Initially you’ll be individualistic, but be sure to listen to one another”.

From left to right: Jury members exchange during the mise en condition with Shields-Argelès participating (© Claire Perrot); Claire Perrot starts the tour de table (© Thierry Petit).

The mise en commun’s egalitarian character connects to the jury terroir’s pedagogical mission. It was during mise en commun that early participants gained confidence as they “heard” their attunement. As one “trailblazer” reflected:

“Once that initial shock passed (…) and we sat around a table taking turns, and we realized that if I had found chocolate and around the table there were 5 or 6 out of 10 who had also found chocolate, we said to ourselves, ‘Well, ultimately, this isn’t just random’”.

Even when participants heard their disagreements (and felt frustrated), they were reassured that the final synthesis would emerge from multiple tastings and statistical analysis. Novices who join the jury today continue to learn through others’ observations during mise en commun. Bérodier believed anyone could learn effective tasting, broadening participation and empowering chain members to articulate sensory experiences: “Farmers have incredible sensory memories; they had just never put them into words”. The jury terroir created a space where implicit knowledge could become explicit, particularly for those whose sensory expertise had been historically undervalued.

Descriptive

The language panelists use is descriptive. While commonplace today, this approach was radically new in early years when vocabulary was limited to “mild” (doux) and “nutty” (fruité). Descriptive language aims to account for differences while suspending judgment—an important means of working against ranking reflexes.

In an early conference paper, Bérodier explains that descriptors differ from technical terms (e.g., propionic) used to identify defects. She recognized that quality control vocabulary throughout the chain focused on identifying defects; quality was defined by their absence—a definition aligned with industrial standards. Descriptors, instead, name qualities; Bérodier writes: “a cheese is a quality cheese only if its qualities outweigh its defects”. These descriptors are never “hedonic” (pleasant) or “closed” (characteristic) because such terms “represent a conclusion, not a description”. Instead, descriptors are intended to be open, precise, and discriminating, encouraging panelists to describe a cheese in its “entirety”. A cheese previously labeled as “mild” becomes: “notes of butter, milk caramel, hazelnut and a little vegetal”42. This vocabulary emerges through careful consideration of which terms resonate with local experience, as we explore further in our discussion of embodied practice.

This descriptive approach enables jury terroir members—like anthropologists—to account for differences while suspending judgment, avoiding hierarchies (like ‘rustic’ versus ‘refined’). In anthropology, describing supports an ethical stance treating all cultures as different but equal43. Similarly, jury terroir panelists use description to treat all Comté cheeses as different but equal—a form of sensorial relativism. As one panelist states: “the jury terroir is there to speak of all the richness in the taste of one Comté, in order to talk about the diversity of Comtés”.

In both sensory and cultural encounter, using a descriptive language, that works to explicitly avoid judgement, has the potential to articulate and value diversity. We, anthropologist-authors and jury terroir members, engage in “thick description”44 to build a holistic view through microscopic focus, and understand our practice as interpretive. One jury member articulates this: “You know there’s no such thing as Truth, huh? You don’t say how cheese is, you say how you sense it”. Because a multispecies encounter between living cheeses and humans forms the core of the jury’s work, descriptive language provides the fundamental skill for the “arts of noticing”—engaging all senses, relying upon “polyphonic assemblages”, and freeing utopic imaginations45.

Embodied and Felt

At the onset, the jury terroir reappropriates Jacques Puisais’ lists of descriptors, deciding which ones were meaning-full for them, and which were not. As Bérodier explained while reviewing lists with Shields-Argelès:

“‘Rose petals’, never used. ‘Buckwheat’, never used. ‘Licorice’, it happens, but rarely. Look here, ‘havana’, like the cigar. We took it out. What stood out was the vegetal, strong, fermented side, and the horse side. It’s true that for me, whose grandfather was a blacksmith, it is easy to find ‘horse’ on a cigar”.

This process of adaptation continues through exchanges during the mise en commun. This is also where intergenerational transmission occurs. Several interlocuteur recalled with affection senior members of the early jury terroir, like cellar master Maurice Bressoux. “I always knew that a freshly pressed cheese that smelled of ‘hazelnut’ would be a good cheese”, he told them. New discoveries also enrich the vocabulary, which evolves over time; one panelist, after a vacation abroad, introduced “pineapple” as a descriptor.

These collective experiences are emotionally charged. Bérodier described the early years as “a real adventure!” combining doubt and uncertainty (“what’s the point?”; “where are we going?”) with wonder, hope, and camaraderie. That participants vividly recall these emotions years later speaks to their significance.

We envision the jury terroir, with the mise en commun at its heart, as a revitalization ritual. Such practices are not conservative reactions, but creative, emotionally-charged and locally embedded responses to profound transformations linked to the dynamics of modernization and globalization46. In this view, rituals of revitalization are tactical manoeuvres; structure, ruled and collective but tactical nonetheless. As Reuter and Horstmann observe, such rituals are “motivated by the desire to consciously shape one’s own future” and represent “essentially utopian” forms of deliberate social engineering47. Two qualities make this ritual particularly powerful: smell’s inherent liminal nature; and the structured, egalitarian practice of sharing smells (within the mise en commun) that channels and strengthens this sensory power.

Smell offers distinctive advantages for the imaginative reconfiguration processes central to utopic process. Through retro-olfaction, aromas are experienced at the threshold: spanning boundaries between the inside and outside of our bodies, between self and other, time and space48. Smells evoke memories as emotionally-charged wholes49. Olfactive memories are simultaneously individual and collective, shaped by shared environments and practices. Many of the aromatic descriptors chosen by the jury terroir function as symbols that recall different “domains of experience” of the chain and region50. Jury members refer to their aromatic descriptors as the “words of the terroir”, acknowledging how memory influences their recognition and emotional impact. These properties make smell particularly potent in ritual contexts. As neuroanthropologist Robert demonstrates, ritualized sensory activities can physically change our brains; a particularly powerful argument for the transformative potential of such practices51.

Pictorial representation of some of the ‘domains of experience’ (the fruitière, farm, garden, forest and pasture) represented by aromatic descriptors.

From left to right: cheesemaker (© Claire Perrot), barn (© Leyla Halabi, AUP class of 2017); garden (© Shields-Argelès); landscape (© Anne Elder, AUP class of 2017).

Paradoxically, difficulty articulating smells also strengthens connection. Because smells are elusive and resist verbalization52, the collective experience of smelling together within the mise en commun creates a pathway for communication, granting agency to both smellers and what is smelled. Several jury members described their wonder upon first experiencing sensory attunement during this process. At the same time, this practice attributes agency to the cheeses themselves, as they reveal themselves or not to the group. Members sometimes even refer to cheeses as speaking subjects (in passing and without much ado): “The cheeses do not always speak to us in the same way; some are more or less talkative”. This practice thus brings participants beyond mere synesthesia (the union of senses)53 toward what Carbonell terms “panesthesia”—“a form of attunement that promotes an awareness of all human senses in order to form an active correspondence with the more than human”54.

When jury members refer to the cheeses as speaking subjects, Shields-Argelès recalls her many visits, with AUP students, to the ‘old’ Comté museum (which closed its doors in 2021). Above are screenshots taken from the film which began the visit. It was narrated by a wheel of Comté cheese.

Through repeated mise en commun sessions, participants achieve what Carbonell calls “thick emplacement”—“the process of sensing and making sense as a richly detailed, contextualized, multisensory and affective attunement with place”55. This extends traditional ritual theory by incorporating conscious techniques that decenter the human, opening participants to new forms of experience. The shared aromatic language, collective sensory interpretation, and dialogue with the cheese creates this thick emplacement, transforming the mise en commun from merely a social revitalization ritual into one that revives cross-species relationships as well.

As the jury terroir and its mise en commun continues, so does the possibility for this encounter. A retired farmer who recently joined the jury terroir, when asked by Shields-Argelès in a 2014 interview why he chose that activity, replied:

“To look up close! Like when you lie down in a field of grass and look at the earth. It’s amazing what you see! You see things that you never noticed before. (...) Mais oui! Some people don’t know that a field is teeming with life. They just don’t pay any attention. And yet, that is part of the existential chain of life. (...) And, you know, we are not even really at the top of the chain, because we are fragile, somewhere in the middle. So, it’s about returning to these things. You know, there are generations of farmers who never bent over in their fields to wonder at all the life that abounds there”.

Tasting in the jury, like lying down in a field and closely observing the life teeming there, is a sensorial experience focused on the minutiae of everyday life that gives way to a higher order reflection and sense of connection. James Fernandez refers to this as the “‘shock of recognition’ of a wider integrity of things”—a sharp feeling provoked by “the collapse of separation into relatedness (...) the recognition of a greater whole”. Through the “figurative language and the argument of images” involved in exchanging aromatic descriptors, jury members achieve “a wider and more transcendent view of things”56. Fernandez calls this experience, returning to the whole.

Extending the Thread, (Re)imagining the Whole

When sharing her ethnographic analyses with others outside the chain, Shields-Argelès was surprised that the farmer’s citation in particular touched her audience. This was also true for Eliza Schwartz and Annika Lovgren, co-authors of this article, who agreed at the onset that this citation would be at the heart of Lovgren’s film project. Thus, a thread is drawn from farmer to ethnographer to student.

This resonates with something that ‘Tas’ Marmier, a Comté farmer and jury terroir member, often told AUP students while they were visiting his farm and fruitière. The whole idea of such a trip, he said, was not to encourage them to consume Comté; there was only so much of that to go around in any case. It was, instead, to give them a sense, through this one specific example, that other sets of relationships—with their food, with one another and the wider world—were possible. The idea then was to bring such ideas home in order to create similar processes in other places. We might consider this a moment of utopic transference, when an imaginative spark is ignited, or a thread drawn from one site to the next, from one set of practices to another through a socio-sensory encounter.

Many of Shields-Argelès’ students attempted this through research projects, directed studies, film and photography projects, internships and career paths. We could view these as cooperative experiments with Shields-Argelès as professor-mentor. Of course, such processes are also contingent and incomplete, filled with tensions.

Here we represent an encounter between ‘Tas’ Marmier and AUP students that extends to another cooperative project, the Food without Borders project.

From left to right: Marmier, Shields-Argelès and AUP students in 2017 (© Jean-Claude Uzzeni); ‘Tas’ Marmier speaking to students (© Alex Bilodeau); Beth Grannis at the fruitière (© Alex Bilodeau); Shields-Argelès and Grannis working together (© Charles Talcott); and a screenshot of one of the project’s final films.

Here we present the latest collaborative experiment. The following film is Annika Lovgren’s production, a film major and anthropology minor at AUP. Throughout our research, this cinematic work and our written analysis developed in parallel, with each process informing the other. Lovgren offers a brief, evocative cinematic portrayal of our ethnographic exploration of the mise en commun. Inspired by experimental filmmaker Isabelle Carbonell, she uses close-ups, image layering and movement to evoke the “thick emplacement” and “panesthesia” experienced in the jury57. She also draws from sensory ethnographers who use walking and tasting as place-making practices that create connections and inspire change58. We share the film as a different but valuable way of engaging with the jury terroir as utopic process, hoping that the rencontre between visual and textual elements brings something new to our audience.

In the film Mise en commun, directed by Annika Lovgren, a thread connects the farmer, the ethnographer, and the student.

Toward Concrete and Resonant Utopianism: Power, Practice and Possibility

Of course, while the jury terroir can create powerful sensorial experiences for some panelists, not all search for or experience transcendental connection between place and product. Nor does this practice exist in isolation; rather, it operates within institutional constraints and market realities. These constraints, however, do not diminish the jury’s transformative potential. The practice is maintained and extended, generating both concrete interventions and resonant spaces that reverberate beyond its immediate context.

The Limits and Tactical Power of Cooperative Taste

Let’s begin with limits. Because sensing often produced believing in the early jury, many originally hoped to generalize the cooperative tasting practice throughout the chain. This never materialized. Jean-Jacques Bret explains:

“If we didn’t generalize it more, it is because it is too sophisticated (...)They (chain members) have an empirical knowledge of their product (...) they do not necessarily feel the need to define it with these exact terms. (...) When you eat a piece of Comté and, after a certain number of experiences at the jury terroir, you are able to say that it smells like dark chocolate or brioche; well, that irritates people”.

Paradoxically, despite attempts to make the practice accessible, tasting in this manner often remains associated with elitism and social hierarchies outside the jury terroir proper.

Additionally, understanding Comté as diverse flavors linked to fruitières and their terroirs remains largely invisible in the marketplace, even in France. A plan to codify the “crus of Comté” was voted down within the commissions of the CIGC in the early 2000s. Aging cellars remain front-facing to consumers outside the region, while fruitières remain largely invisible. Generally speaking, consumers associate taste variability with age, while season, terroir, and the fruitière structure itself remain hidden from view.

Despite these limitations, however, cooperative taste remains an important tactical power within the chain. We briefly examine the reasons for this below.

Concrete Utopianism: Structural Interventions and Power

First the jury’s cooperative taste practice, guided by Bérodier and others, leads to concrete utopianism — one that “never overthrows the system entirely” but identifies “concrete interventions that point beyond the logic of the existing order”59. At the turn of the last century, the jury’s aromatic descriptors become codified first as a technical language in scientific publications, then as identity language in fruitière identity cards elaborated for restitution meetings (and also covered by the local press), and finally as legal language in production specifications governing the chain. This transformative process, as aromatic descriptors are translated into new forms of authoritative language, represents a tactical reconfiguration of power that centers fruitières and their terroirs against homogenizing market forces. These concrete extensions enabled the jury to wield influence disproportionate to its size, embedding its terroir foodview into institutional structures.

Another form of concrete utopianism in this case is the extension of the jury’s cooperative taste practice into pedagogical tastings for the general public. In the early 2000s, the CIGC developed a television advertisement aimed at communicating the “aromatic diversity” of Comté. However, when they tested the ad, few understood the message and the campaign was abandoned. At this moment, they realized that “the message concerning aromatic diversity” was “educational and not promotional”60. The jury terroir’s practice was then retooled for public education, with some jury members leading tastings (and, indeed, some still do). These pedagogical tastings often target amateur audiences, and run alongside traditional forms of communication like TV advertisements61.

Importantly, both the jury terroir and these concrete interventions are grounded in a commitment to the transparent and equitable distribution of benefits62 throughout the chain — reflecting a wider commitment to solidarity. As “Tas” Marmier often told my students: “the sirens of modernity repeatedly sing of the promises of individualism, but members of the chain must remain collectively organized and in solidarity. And solidarity needs to be organized”. Without this equitable economic structure, the jury’s sensory work and collective vision would be reduced to empty discourse rather than meaningful transformation.

Resonant Utopianism: Creating Oases of Possibility

Building on this foundation of concrete utopianism, we propose the concept of resonant utopianism to theorize what we earlier described as utopic transference.

What farmer ‘Tas’ Marmier described was not simply knowledge transfer but what sociologist Hartmut Rosa would call a “resonant relationship”—a responsive, meaningful connection where both parties are transformed63. The transmission from farmer/jury terroir panelist to ethnographer to student creates “axes of resonance” that are vertical (connecting to nature and terroir), horizontal (linking people), and diagonal (transform sensory work into meaning-full practice). This resonance manifests in moments of discovery and connection, whether in jury members recognizing subtle variations in taste profiles or in students experiencing the revelation that cheese can embody a cooperative cheese dairy.

We propose resonant utopianism, or the cultivation of “oases of resonance” that provide a partial refuge within alienating systems while fostering attunement, responsiveness, and transformation64. These resonant spaces do not overthrow existing structures but point toward alternative relationships with the world, ourselves, and others. Importantly, within such oases, embodied practices, like cooperative tasting, generate affective connections that contain the potential to eventually transcend their immediate context, creating ripple effects that inspire similar practices across different domains.

In this way, our methodological approach—ethnographic immersion combined with collaborative pedagogical experimentation and multimodal representation—is not merely studying utopianism but actively aiming to extend it. By engaging students in sensory ethnography, collaborative productions, as well as creative projects, we extend the jury’s cooperative practice while transporting it into new contexts. In the end, our methodology resonates with the jury terroir’s: it extends across time, harnesses sensory and social methodologies for both pedagogical exchange and scientific production. It is also then, a form of utopian practice, creating spaces where alternative relationships to food, place, and community can be experienced, felt and (re)imagined.

Finally, concrete and resonant utopianism work in tandem. The jury creates concrete interventions through publications and specifications, while generating resonant experiences that extend beyond its immediate context. This relationship contains a productive tension—concrete interventions provide legitimacy, while resonant extensions maintain affective vitality that institutional codification might diminish. Each form needs the other—concrete without resonant becomes bureaucratic, while resonant without concrete risks becoming ephemeral. The jury thus demonstrates how sensory practices can both restructure power relations and create meaningful experiences pointing toward alternative food futures.

Conclusion: From Salvage Ethnography to Future Possibilities?

In sum, we propose cooperative taste as a utopic practice emerging from the jury terroir—one defined by egalitarian exchange and thick description that actively resists standardization. Through shared embodied experiences, this practice creates new food imaginaries while avoiding the hierarchical rankings that often dominate taste evaluation. Our analysis shows how the jury’s cooperative approach generates both concrete institutional changes and expansive possibilities that extend well beyond its immediate context.

Outside the case examined in this paper, we imagine that cooperative tastings take diverse forms and operate across a variety of contexts, and are perhaps especially useful in pedagogical contexts65. Like de Certeau’s pedestrians or Giard’s home cooks, the tactical actors creating and participating in such activities are dispersed across time and space, and sometimes mistake allies for strategic opponents through the lens of national differences. By identifying a wide range of practices as forms of cooperative taste, we might recognize, and eventually refine, shared resistance tactics that transcend cultural reification.

To close, what of the jury terroir today? This study could be considered a kind of ‘salvage anthropology’, one that documents key cultural practices as they begin to disappear. Shields-Argelès carried out the bulk of her research from 2012-2018, as the generation that created the jury terroir in response to the challenges of the 1980s-90s was retiring and passing leadership to a new generation. Today, the chain is facing new challenges, and just concluded another set of revisions to its production specifications, aimed specifically at addressing environmental concerns. The jury terroir continues under new leadership, but it too is changing. For example, during our last visit in June of 2024, they were experimenting with computer software that offered instantaneous synthesis. There is ongoing discussion about how to use this technology while maintaining the mise en commun.

An unexpected field encounter suggests that cooperative tasting should remain important for the chain. This past June while visiting with artist Thierry Moyne, who paints with local soils and waters, we discovered a few of his creations hung along a trail beside waterfalls—abstract works on black canvas made with limestone deposits from the falls.

A painting by Thierry Moyne alongside the falls.

He explained that increased tourism is wreaking havoc on these natural sites. He hoped that by installing such paintings on the falls he could give voice to them, creating a different connection with visitors that might encourage a sense of responsibility.

This is not so different from the practices of the jury. By giving voices to the cheeses through a cooperative tasting practice, they led the way through a period of acute change. We can only imagine that listening to the cheeses, like listening to the falls, could play a key role in processes that will impact both humans and more-than-humans in the not-so-distant future.

Notes

1

We thank the John H. Lewis Faculty Development Fund at The American University of Paris (AUP) for generously supporting our research.

2

A socio-sensory reflexivity demands engagement with process. Consider your positionality: What emotions and expectations shape your approach to this text? What constitutes “reading” for you? What informs your assumptions about tasting? On reading as positioned, embodied and affective practice, see: Jane Thompkins, “Deep Reading,” JAEPL, no. 22, Winter 2016-2017, pp. 1-5.

3

We translate “filière” as “chain” (not “supply chain”) as it better reflects our interlocutors’ usage. While “supply chain” emphasizes markets, chain members use “filière” to highlight collaborative production and solidarity. As one farmer explains: “The word ‘chain’ represents something indissoluble... If you break one link... If you don’t have the cheese ager, cheesemaker, or farmer, you don’t have Comté cheese.”

4

Gary Wilder, Concrete Utopianism: The Politics of Temporality and Solidarity, New York, Fordham University Press, 2002, p. 9.

5

J.K. Gibson-Graham, “Rethinking the Economy with Thick Description and Weak Theory,” Current Anthropology, vol. 55, supplement 9, August 2014, S147-S153.

6

Ben Highmore, “Taste as Feeling,” New Literary History, vol. 47, no. 4, 2016, pp. 547-566.

7

Carole Counihan, “Mexicanas’ Food Voice and Differential Consciousness in the San Luis Valley of Colorado,” in Carole Counihan et Penny Van Esterik (eds.), Food and Culture, London, Routledge, 2012, pp. 187-200; Chela Sandoval, “U.S. Third World Feminism: The Theory and Method of Oppositional Consciousness in the Postmodern World,” Genders, vol. 10, no. 1, 1991, pp. 1-24.

8

Michael Carolan, “The Wild Side of Agro-Food Studies: On Coexperimentation, Politics, Change, and Hope,” Sociologia Ruralis, vol. 53, no. 4, 2013, https://doi.org/10.1111/soru.12020. Paul Stock, Michael Carolan, and Christopher Rosin, “Food Utopias: Hoping the Future of Agriculture,” Food Utopias: Reimagining Citizenship, Ethics and Community, London, Routledge, 2015.

9

Theodoros Rakopoulos, “Cooperatives,” in Felix Stein (ed.), The Open Encyclopedia of Anthropology, Facsimile of the first edition in The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Anthropology, 2023 (2020). Online: http://doi.org/10.29164/20coops.

10

Michel Vernus, Coopératives : Un Capitalisme Jurassien, Participatif et Solidaire, Paris, Belvédère, 2014.

11

Roland Barthes, “Toward a Psychosociology of Contemporary Food Consumption,” Food and Culture, London, Routledge, 2018, pp. 13-20; Mary Douglas, “Deciphering a Meal,” Daedalus, vol. 191, no. 1, 1972, pp. 61-81; Claude Lévi-Strauss, “The Culinary Triangle,” Partisan Review, vol. 33, no. 4, 1966, pp. 586-595.

12

David Howes, Sensorium: Contextualizing the Senses and Cognition in History and Across Cultures, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2024; David Le Breton, Sensing the World: An Anthropology of the Senses, London, Routledge, 2020.

13

Sidney W. Mintz, Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History, London, Penguin, 1986.

14

Pierre Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, London, Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1984.

15

Constance Classen, David Howes, and Anthony Synnot, Aroma: The Cultural History of Smell, London and New York, Routledge, 1994; Claude Fischler, “Food, Self and Identity,” Social Science Information, vol. 27, no. 2, 1988, pp. 275-292.

16

Geneviève Teil and Antoine Hennion, “Discovering Quality or Performing Taste? A Sociology of the Amateur,” Qualities of Food, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2004, pp. 19-37.

17

Steven Shapin, “The Sciences of Subjectivity,” Social Studies of Science, vol. 42, no. 2, 2011, pp. 170-184.

18

Sarah Pink, “An Urban Tour: The Sensory Sociality of Ethnographic Place-Making,” Ethnography, vol. 9, no. 2, 2008, pp. 175-196.

19

Amy Trubek, The Taste of Place: A Cultural Journey into Terroir, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2008.

20

David Sutton, Remembrance of Repasts: An Anthropology of Food and Memory, New York, Berg, 2001.

21

Priscilla Parkhurst Ferguson, “A Cultural Field in the Making: Gastronomy in 19th Century France,” American Journal of Sociology, vol. 104, no. 3, 1998, p. 626.

22

Michel Vernus, Coopératives : Un Capitalisme Jurassien, Participatif et Solidaire, Paris, Belvédère, 2014.

23

Gökçe Günel, Saiba Varma, and Chika Watanabe, “A Manifesto for Patchwork Ethnography,” Fieldsights, June 9, 2020.

24

Luce Giard, “The Nourishing Arts,” in Michel de Certeau, Luce Giard, and Pierre Mayol, The Practice of Everyday Life. Volume 2: Living and Cooking, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1998, pp. 151-170; Nadia Seremetakis, The Senses Still, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1996.

25

Dara Culhane, “Sensing,” in Danielle Elliott and Dara Culhane, A Different Kind of Ethnography: Imaginative Practices and Creative Methodologies, Toronto, University of Toronto Press, 2017, p. 49.

26

Sarah Bowen, “The Importance of Place: Re-territorializing Embeddedness,” Sociologia Ruralis, vol. 51, no. 4, 2011; Valéry Elisséeff, “Le Comté AOP : Une réussite collective au cœur du territoire,” Journal de l’École de Paris du management, no. 127, 2017, pp. 8-13.

27

Comté USA, “On the Farm”. Online: https://comte-usa.com/about-comte/on-the-farm/.

28

See also: Jean-Jacques Bret, Les Héritiers du Comté : résistance et renaissance de 1945 à 2013, Dijon, Raison et Passions, 2021.

29

David Howes, “The Science of Sensory Evaluation: An Ethnographic Critique,” in Adam Drazin et Susanne Küchler (eds.), The Social Life of Materials: Studies in Materials and Society, London and New York, Bloomsbury Academic, 2015, pp. 81-97; Jonathan Lahne, “Sensory Science, the Food Industry, and the Objectification of Taste,” Anthropology of Food, n° 10, 2016.

30

CIGC, “Le Jury Terroir Comté,” Les Nouvelles du Comté, no. 68, 2009.

31

Jean-Claude Monnet, Florence Bérodier, and Pierre-Marie Badot, “Characterization and Localisation of a Cheese Georegion Using Edaphic Criteria (Jura Mountains, France),” Journal of Dairy Science, vol. 83, no. 8, 2000, pp. 1692-1704.

32

Participants do not change their initial evaluations on the tasting sheet but can move toward shared descriptors during discussion.

33

A single mise en commun from 2014 is described in prior publications, see Christy Shields-Argelès, “A Cooperative Model of Tasting: Comté Cheese and the Jury Terroir,” Food, Culture and Society, vol. 22, 2019, pp. 168-185.

34

Michel de Certeau, Luce Giard, and Pierre Mayol, The Practice of Everyday Life. Volume 2: Living and Cooking, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1998.

35

Carole Counihan and Susanne Højlund (eds.), Making Taste Public: Ethnographies of Food and the Senses, London, Bloomsbury, 2018.

36

Megan Laws, “Egalitarianism,” in Felix Stein (ed.), The Open Encyclopedia of Anthropology, 2023 (2022). Online: http://doi.org/10.29164/22egalitarianism.

37

Philippe Urfalino, “What is Collective Deliberation?,” Politika, published online on 08/04/2019, accessed on 28/04/2025. URL: https://www.politika.io/en/notice/what-is-collective-deliberation.

38

Christy Shields-Argelès, “A Cooperative Model of Tasting: Comté Cheese and the Jury Terroir,” Food, Culture and Society, vol. 22, 2019, pp. 168-185.

39

Geneviève Teil and Antoine Hennion, “Discovering Quality or Performing Taste? A Sociology of the Amateur,” Qualities of Food, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2004, pp. 19-37.

40

Ivan Illich, Tools for Conviviality, New York, Harper & Row, 1973.

41

Raúl Matta, “Towards Convivial Foodscapes,” in Tristan Fournier (ed.), “Utopies nourricières,” Politika, published online on 05/06/2024, accessed on 28/04/2025. URL: https://www.politika.io/en/article/towards-convivial-foodscapes.

42

Florence Bérodier, “Notion de Cru en Terroir de Comté,” Unpublished, Actes du Colloques, Les Mots pour Dire le Goût, 1992.

43

The notion of cultural relativism, attributed to American anthropologist Franz Boas, has also faced criticisms; it can inadvertently lead to cultural reification.

44

Clifford Geertz, “Thick Description: Toward an Interpretive Theory of Culture,” in The Interpretation of Cultures, New York, Basic Books, 1973, pp. 3-30.

45

Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2015.

46

Christy Shields-Argelès, “Tasting Comté Cheese, Returning to the Whole: The Jury Terroir as Ritual Practice,” in Making Taste Public: Ethnographies of Food and the Senses, London, Bloomsbury, 2018, pp. 83-96.

47

Thomas Reuter and Alexander Horstmann, “Chapter One: Religious and Cultural Revitalization: A Post-Modern Phenomenon?,” in Faith in the Future: Understanding the Revitalization of Religions and Cultural Traditions in Asia, Leiden, Brill, 2012, pp. 1-14.

48

Hanna Gould and Anne Allison, “Smelling Death: New Necro-Scents in Contemporary Japan,” Unpublished conference paper, NOS-HS Exploratory Workshops in Olfactory Cultural Studies Project, Ålesund/Runde, Norway, 4-6 September 2023.

49

David Sutton, Remembrance of Repasts: An Anthropology of Food and Memory, New York, Berg, 2001.

50

James Fernandez, Persuasions and Performances: The Play of Tropes in Culture, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1986.

51

Robert Turner, “Ritual Action Shapes Our Brains: An Essay in Neuroanthropology,” in Michael Bull and Jon P Mitchell (eds.), Ritual, Performance and the Senses, London, Bloomsbury, 2015.

52

Anna Tsing, The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2015.

53

David Sutton, Remembrance of Repasts: An Anthropology of Food and Memory, New York, Berg, 2001.

54

Isabelle Carbonell, Attuning to the Pluriverse: Documentary Filmmaking Methods, Environmental Disasters, and the More-Than-Human, Ph.D. Dissertation, University of California, Santa Cruz, 2022, p. 184.

55

Isabelle Carbonell, Attuning to the Pluriverse: Documentary Filmmaking Methods, Environmental Disasters, and the More-Than-Human, Ph.D. Dissertation, University of California, Santa Cruz, 2022, p. 184.

56

James Fernandez, Persuasions and Performances: The Play of Tropes in Culture, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 1986, pp. 205-206.

57

Isabelle Carbonell, Attuning to the Pluriverse: Documentary Filmmaking Methods, Environmental Disasters, and the More-Than-Human, Ph.D. Dissertation, University of California, Santa Cruz, 2022, p. 184.

58

Sarah Pink, “An Urban Tour: The Sensory Sociality of Ethnographic Place-Making,” Ethnography, vol. 9, no. 2, 2008, pp. 175-196; Sarah Pink, Doing Sensory Ethnography, London, Sage Publications, 2009.

59

Gary Wilder, Concrete Utopianism: The Politics of Temporality and Solidarity, New York, Fordham University Press, 2022.

60

Interview with Aurélia Chimier, Director of Communications, CIGC.

61

Diane Chabrol and José Muchnik, “Consumer skills contribute to maintaining and diffusing heritage food products,” Anthropology of Food, no. 8, 2011. Online: https://journals.openedition.org/aof/6847.

62

Sarah Bowen, “The Importance of Place: Re-territorializing Embeddedness,” Sociologia Ruralis, vol. 51, no. 4, 2011.

63

Hartmut Rosa, Resonance: A Sociology of Our Relationship to the World, Cambridge, Polity, 2019.

64

Tristan Fournier and Sébastien Dalgalarrondo (eds.), Rewilding Food and the Self: Critical Conversations from Europe, London, Routledge, 2022, p. 9. This concept also aligns well with Fournier and Dalgalarrondo’s ideas about "rewilding" as creating opportunities for new relationships with the world, other people, and other beings.

65

Haruka Ueda, Food Education and Gastronomic Tradition in Japan and France: Ethical and Sociological Theories, Oxford, Routledge, 2023; Jennifer Coe and Erik C. Fooladi, “Multisensory Experiences with and of Food: Representing Taste Visually and Verbally During Food Ateliers in a Reggio Emilia Perspective,” Cambridge Journal of Education, 7 February 2025. Online: https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2025.2459924.