An interview with Barbara Taylor on her book The Last Asylum: A Memoir of Madness in Our Times

The intellectual and cultural historian, Barbara Taylor, is currently professor of humanities at the Queen Mary University of London. Her work centres on feminist theory, psychoanalysis and history, and the Enlightenment, “with a special interest in the subjective dimension of historical change” – as she writes on her personal academic webpage. In 1983, early in her career, her book, Eve and the New Jerusalem: Socialism and Feminism in the 19th Century, was published by Virago Press. It went on to win that year’s Isaac Deutscher Memorial Prize. She was also a member of the editorial collective of the History Workshop Journal. In the 1980s, her mental health began to deteriorate and she eventually suffered a breakdown, which cost her her status as an up-and-coming young historian. Following a period of intensive psychoanalysis, she checked herself into what was once Europe’s largest psychiatric hospital: the Friern Hospital (formerly Colney Hatch Lunatic Asylum). This lengthy period of illness, in which psychoanalytic and psychiatric therapies were the principal activities of daily life, was to rule out any kind of intellectual work. Discharged in 1993, she embarked on a new life, first finding a job at a London university and then, a few years later, meeting her partner and creating a family. Her comeback as a historian would be her 2003 work on Mary Wollstonecraft. This personal and – it must be said – traumatic experience is not only part of Taylor’s biography, however. Its beginning, its course and its end became the subject of a book in which her special interest, the subjective dimension of historical change, took on particular significance.

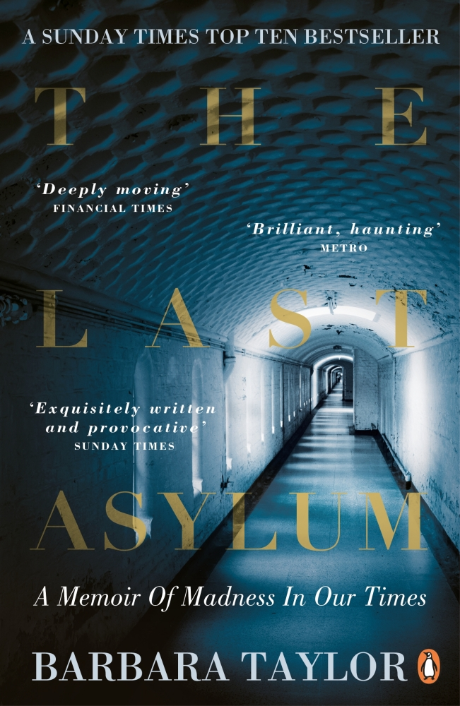

In 2014 Barbara Taylor’s book The Last Asylum. A Memoir of Madness in Our Times was published by Penguin Books. It is, she writes

“the story of my madness years, set inside the story of the death of the asylum system in the late twentieth century. The book is a historical meditation on mental illness: primarily my own illness but also that of the millions of other people who have suffered, are suffering, will suffer from mental illness” (p. xi).

The volume is divided into three parts, of which the first may be considered the most introspective and psychoanalytical. By blending fragments of her family story, summaries of therapy sessions with the psychoanalyst (v. in the book) who accompanies her throughout, and her dreams and current thoughts, the author seeks to portray her descent into serious mental illness. She writes:

“for many people, experiencing the past as past, allowing it to become truly historical, is very difficult. It involves uncovering aspects of our lives, especially our early lives, which we have forgotten or have never really known about, except perhaps as occasional spasms of mind or body, disturbing dreams, strange movements in the blood... […] The sources of self run deep. In my case, exploring them required me to become a historian of my own life, through the peculiar and demanding labour of a long term psychoanalysis, of which The Last Asylum is also an account” (p. xii-xiii).

The reader becomes the witness of a delicate and measured intimacy which discusses mothers, fathers, sex, drugs, solitude, physical and emotional pain, all bound up together. Nothing is revealed solely for the pleasure of exposing the intimate. Rather, the whole of the first part is an attempt to make public through writing the way in which a person enters into madness – the how rather than the why.

The second part may be regarded as a genuine encounter between subjective experience and the mental health system. Admitted to Friern Hospital in 1988, Ms. Taylor tells the story of how she lost all sense of herself as a historian. This is powerfully addressed in the chapter First Day:

“The memories recounted in this book have not been easy to retrieve. But the confusion of self that accompanied my admission to Friern makes recalling that time especially difficult. My diary entries dried up for a time: who would write them? I felt naked, stripped of my identity, my history. When I told a nurse that I had published a book, he smirked at this piece of blatant make-believe. Would I ever write another book? […] I mourned the woman I thought I had been” (p. 119).

At the same time, this is the most properly historical part. An entire chapter is devoted to the history of Friern as an example of the western psychiatry that developed out of reformist optimism before adopting an anti-institutional and anti-welfarist approach. Ms. Taylor’s stay in Friern coincided with the demise of the public mental health system: “I was formally discharged in 1992. Friern closed the following year. By the end of the decade nearly all the mental hospitals had gone. I had lived through the twilight days of the Asylum Age” (p. xi). This second part also offers an interesting reflection on the relationship between psychoanalysis and psychiatry in an English context before returning to more subjective topics, including the importance of friendship, the encounter with other patients. The chapter entitled Mad Women is an evocative description of some female patients, which also offers insights into gender issues. Finding a “new home”, a loony bin full of violence and misery on the one hand but of solicitude, camaraderie and warmth on the other, Ms Taylor provides from personal experience a point of view that is less critical and condemnatory of a venerable and gloomy place. Her sensitive and touching récit does not induce the same feelings as Goffman’s popular description in Asylums. Rather she finds human relations, little moments of kindness, of listening to other patients, a gradual reconciliation with selfhood. “Would I have forgone those long months in Friern? Absolutely. But I don’t regret them” (p. 121).

Part Three is about change. In 1990, Barbara stops drinking. After a period as a day patient at Friern, Barbara moves to a community care hostel, where she meets new friends and encounters a totally different type of care. Her psychoanalysis reaches a turning point. Barbara is getting better, she begins to visit friends, to travel, to write, and in 1993 she has a new job at a London university. The transition has taken several years from being discharged from Friern, via her journey through the community care centre, and on to a new, autonomous life. Ms. Taylor describes the change in terms of Winnicott’s theory of mother-baby separation: by gradually distancing herself from therapy, the subject gains awareness of her own existence. The cure, which respects the need for a slow, careful and undamaging leave-taking, particularly with V., takes more than ten years. “Life post-discharge felt both familiar and strange. I’m like a building under reconstruction, […] same old materials, new foundations”.

The book ends with a reflection on the current imperatives of the mental health system: independence, recovery, choice, risk, brain chemistry – seen by the author as so much Orwellian rhetoric. The author reveals her doubts, about the confusing concept of “independence”, for example, recalling that it is impossible to instil independence when mental illness is too severe and that she herself never had any choice about her treatment or any other aspect of her care. A serious and attentive look at the language of mental health policy shows that financial and political aims can inappropriately change the direction and impact of mental health care. The effects of the service users’ movement, the “open care” system, liberal care policies, the politics of recovery – recovery strategies, Recovery Colleges, recovery teams, – everything seems to support the idea that the best way to heal is to encourage individuals “to minimize the impact of their symptoms on their daily lives. In theory, this seems like an excellent idea. […] But is this what is happening? The answer would seem to be no. […] Mental health care today is a fast-track system geared to getting people back on to their feet, and back into work, as quickly as possible” (p. 251). We are in a period of chaos, where short-term therapies combined with an excess of DSM definitions and chemical treatments, together with a difficult and somewhat illogical recovery model, leave everyone disoriented – managers, staff and patients. It was in this situation in 2013 that the British Psychological Society formally attacked the psychiatric system, casting doubt on the biomedical model of mental illness, only a few days before the publication of the latest version of DSM1.

The psychiatric system must not forget the importance of personal needs and the individual patient’s life story:

“without history, people disappear. […] The personal past often weighs heavily on people with mental disorders. Lightening that burden – by revealing it, understanding it, sharing in it – is a vital part of mental healing. A psychiatric system that denies this to people needs to take a hard look at itself, to ponder its own refusals and deficiencies before setting out to remedy the ills of others” (p. 263).

We are now better able to understand the public use of Ms. Taylor’s personal past as well as the tension between intimate life and public sphere that she tries to portray:

“What would happen to me today? […] The simple answer relates to what I needed most: asylum, a safe place to be, ‘a stone mother’ to hold me for as long as I required it. […] The story of the Asylum Age is not a happy one. But if the death of the asylum means the demise of effective and humane mental health care, then this will be more than a bad ending to the story: it will be a tragedy” (p. 263-264).

Interview

— Let’s start by talking about your approach to this book. It's hard to classify and, from my personal reading, it seems to be a sort of crossover, a “metissage”: there is a novelistic side, a reflexive biographical journal and a historical case study of psychoanalytic treatment and psychiatric institutions. You describe the book as being “about the work of turning the personal past into history”. It is, you might say, a public use of multiple pasts. It would be interesting to hear more about this.

— In a sense, this wasn’t a new approach for me as I had previously written about the lives of other people, particularly the feminist, Mary Wollstonecraft. I had written about her personal life which was very complicated and often quite painful, set in a particular historical world – involving French revolutionary politics and so on. So I think, when I came to tell my own story, I, almost automatically, was sort of doing what a historian does, which was to contextualize my personal history. I had various projects in mind before I started. One was that I was simply going to write a kind of insider’s view of the transition from the asylum system to community care and that I wouldn’t really tell much of my own story and then, over time, when I decided that I would elaborate much more on my own history, it was a question of weaving my story into this much bigger historical transition in which I had participated. So I think there was a sense in which the book was always going to be like that and perhaps if one looks at it, as you say as, life stories, biographies, then they very often do take that path. The difference with mine, of course, is that it’s autobiography, a heavily historicized autobiography, which is what sets it apart, but were I not a historian I am not sure I would have wanted to do it quite that way.

— The use of the past in your work is a very particular one in the sense that it depends more on memories than on sources –

— Yes.

— You wrote “the lived past is never really past, it endures in us in more ways than we understand” as well as “the memories recounted in this book have not been easy ones to retrieve”. You go on to say that you have a lot of personal journals. How did you work on retrieving and reconstructing your story?

— Well, as I say, there was a sense in which I tried to approach myself as a historical subject, in ways that I had used with previous writing about people of the past. I had all these journals and, you know, various other documents and so on from my period of illness. I don’t think, well, I am sure, I wouldn’t have been able to undertake the book at all without them, so it depended on these sources. At the same time, of course, I was also relying on my memories, but my memories as tested against the kind of personal archive that I already had.

I think there is a much richer point, which is about the relationship between a past which was extraordinarily painful and where the memory takes on, I think, a very particular quality. I talk in the opening to the book about the question of memories that are very, very difficult to access; and, in fact, it is probably not really feasible to access them at all in the sense of resurrecting them. One can only catch their echoes, their residues, and the rest is a sort of attempt to imaginatively reconstruct things which are too painful to actually remember in any true sense. I am actually not sure I would quite put it like that. I am not sure I am even capable. I mean we don’t really live memories, they are always mediated by fantasies about the past and so on, and I was very aware of that and very aware that what I was doing was a work of the imagination, of the historical imagination. I needed to find ways of drawing the reader into a story that is complicated, multi-layered and full of very, very difficult feelings and experiences. So the question was always one about having, in terms of the personal materials, a narrative strategy that would allow me to do that and to feel true to my remembering, true to what my sources told me, as true as I felt able to make it.

— There is a question I want to ask you now that you’ve said this. Do you think, if you look back at your book, that you did have a narrative strategy or there were a lot of narrative strategies in the different parts of your writing?

— That’s right, it does move between types of writing, different genres indeed. You get the voice of the memoirist, there is a question of distance here. In a way, through a very direct evocation of particular moments in my experiences and in my analysis, I am trying to bring the readers up close, I am trying to give them some sense of what those experiences were like. When I am writing about the history of the asylum or the history of psychoanalysis in Britain or whatever, I think what comes through there is much more than just the professional historian recounting this aspect of psychiatric history. I wanted that movement between those different voices. It was important to try also to show readers that in one person there could be this coexistence of different ways, different levels of life experience; and that when someone has serious mental illness, it doesn’t wipe out other aspects of the personality. Of course, people who are professional historians, academics or whatever can also suffer from very extreme emotional experiences … so I was trying to bring those two things together.

— In the book, you mention a “collective dimension” to your experiences. Working this way, the book is you and your remembering but there are memories of other people too.

— Yes.

— With this organization of different positions, different experiences and different ways of living the illness, you tried to present something that you share with others. This kind of sharing, this action, is a political action too. I can sense something of the political although not in a mainstream sense.

— Well, I think it does have, certainly, a political dimension. I think the epilogue to the book is very explicit in its strong criticisms of the current state of the mental health services and I came to that critical position through many conversations with people who are inside the system now, either as practitioners, workers or service users. And I think I also tried to locate that criticism of the current system inside a sort of – maybe this isn’t so explicit – broader critique. I suppose what we usually call a new liberal ideology of anti-welfare is a very inhumane way of thinking about the relationship between people and the state in public services and so on. People are expected to earn their way through life with minimal support and this is having a devastating effect not just on people with severe mental health problems but also, of course, right across the spectrum of difficulties. So it was an attack. I feel very strongly in this sense that the current predicament of people with mental illness is part of a much larger problem.

— In this sense, your effort is far removed from Goffman’s Asylums. With this shared use of memories and examples, you open up a more ambivalent and elaborate universe. Certainly, the backgrounds and the periods are not the same but you seem to have a strong leaning toward anti-psychiatry…

— I’m not sure what you mean by that but I don’t in fact have strong views on anti-psychiatry: it was the product of a particular moment and it had many strands to it. What I do feel very strongly about is the decline of psychotherapeutic services and psychoanalytic psychotherapeutic services. In this country we have provisions for behavioural therapy, although it is not as available as the government claims it is. But, in a sort of longer term, depth psychotherapies are not available on the National Health Service and I think this is having a very bad impact on psychiatric care.

Your question then is a very important one because of what you are suggesting about my attitude towards the asylum’s closure, towards the hospitals’ closure, because of course the hospitals’ closures were not driven just by the anti-psychiatric movement, it was an alliance between anti-psychiatry and a government wanting to change mental health care for a whole variety of reasons, including reducing its costs.

But I just want to make clear that my book certainly does talk about the importance of making available institutional care for people when they need it. There is a powerful anti-institutional attitude in western societies now, where institutions cannot be used in dynamic and helpful ways for people and I don’t agree with that at all. I think it depends entirely on how institutions are organized and run. What we need is a combination of institution-based and community-based care to make really effective mental care, but I certainly think the hospital that I was in, for example, should not have been kept open. It wasn’t a good place for people to be looked after and there needed to be much better places, but sadly that’s not what’s happened… And the situation that we are in now is one where people are left too much without access to proper care and the kind of resources they need.

— Thank you, that’s very helpful. I’d like to move on to talk more about your personal view of psychoanalysis and psychiatry. We can see a triple movement in the book. There is the first familiar past, a personal past and, at the same time, the beginning of psychoanalysis and a moment that is described as the fall. There is a chapter called Inferno. We see a fall in the first part, do you agree?

— I am not sure I would say a fall necessarily, although I can see why you use that metaphor, but certainly it often felt like a descent into Hell.

— There is a very profound description of your intimate and personal history in the first part, a description of your treatment and your three admissions to the asylum in the second, and a third part talking about the end of that treatment and your separation from it. With this tryptic, you also describe movement: a fall during the first, psychoanalysis period, a sort of journey – inside Friern Asylum – with your psychiatric treatment and the encounters you had there, and a third moment of change, of cure and rebirth. I don’t want to use religious language but something of a descent into the inferno and a way back do appear. Can you tell us what place you gave to psychoanalysis and psychiatric treatment in this personal journey? Their agencement in your personal experience?

— I understand what you’re asking, I think. These are questions I still ask myself because what the book tries to show in my case, and this is only one person’s story, is that being in analysis, being in the relationship with my analyst, took me into feelings, fantasies and experiences that were in me, but it was as if they were in a terrible frozen wasteland inside me, a kind of terrible sort of dead frozenness, and when dead and frozen things in people begin to come to life again the pain is terrible, and the encounter with myself that happened in the first five-six years of my analysis was truly terrible, excruciating. That’s why I describe it as a descent into hell, but the hell was there already, you know, you don’t go there unless it’s already there. Other people going into analysis wouldn’t experience this. Analysis is a stormy business for people, who are often in trouble, but not like that, not unless they are as ill as I was. I think it’s a big thing for an analyst to take someone on when they realize this is the state of the person. And now… would have I survived that, without the support of my psychiatrist and the institutions? I will never know the answer. I mean, people do die in psychoanalysis and I was certainly running that risk. If I hadn’t gone into psychoanalysis, would I have died? If I had simply tried to muddle through my life? I will never know that either. I think I would probably not have survived but then also one has to ask the question, because the psychiatrist was there, because the institution was there, perhaps that made it possible for my analyst and me to go very, very deep in ways that, maybe without that kind of support, we might not have been able to do. So this is also possible but it’s very difficult to know. My psychiatrist was unusual and this was my great fortune. I had a lot of good fortune in my time of illness but it was having a psychiatrist who was so sympathetic to psychoanalysis, so aware of how difficult it could be, so intelligent about providing effective support so that I could carry on in my analysis, which was very unusual. The way that she used the institutions, not just Friern, but other institutions that I attended, that was very important to me. The hospital and the day centres were both very effective, making it possible for me to carry on and to feel that, whatever happened in the analysis, I was probably going to survive it. I might only survive as a lifelong mental patient. Many times I thought that was what was going to happen. So yes, you are absolutely right, there is a descent into hell, a period of being sustained through the institutions, but at the same time, carrying on the analysis, which goes on being hellish, until there is a real change. I don’t use religious language to describe this change, but I suspect it was the sort of change that underpins much religious experience. It felt like a transfiguration. It was an extraordinary experience. When I set out to write about it, I didn’t think I would be able to find the words for a period when I felt a sort of war in my soul, a battle between life and death. But there wasn’t anything mystical about this. In the book I try to show that in some ways it was very simple. I was in an empty world and then it wasn’t empty anymore: my analyst was there, both in reality and in my inner world. That experience of the psyche opening up to another human being is what happens to healthy people in infancy, so I was a very late developer in that sense.

— Yes, but we feel something like that when we read the book. You said it’s very difficult to give words to this kind of unconscious experience but we do have a little sense of touching it, not to apprehend or to comprehend it in all its fullness but we do gain a sense of it. You achieved that goal, I think.

— That’s very nice to hear, thank you.

— At the same time, and I think it’s connected to what you’ve said, the professional dimension of your life story is almost absent, isn’t it?

— Yes.

— You said you cannot talk about Barbara Taylor as historian in this book.

— Yes, well, it did almost disappear, I mean, I struggled very hard in the early years to keep it going, to try and carry on, I mean, I had to give up my job – I tell that story – and then I tried to continue to do research and I continued to work on History Workshop Journal and so on, but over time these activities became so difficult and finally impossible for me, and the period of time in which I was completely incapable of doing any intellectual work I think probably lasted about four to five years, I suppose. And that was preceded by years in which I could hardly do anything. That’s a long time. I consider I lost a decade, really, in terms of my professional life and I think I did feel that that aspect of my life was completely over by the time I had been in and out of the Friern and at the Whittington. I don’t think I ever really believed that I would have a career again so I was amazed when I found I could pick up the reins again. And this transition from being unable to do anything to being back as a researcher and writer and thinker was quite abrupt. Toward the end of 1991, while I was still at a day centre, I was beginning to look back again at my files from my book on Mary Wollstonecraft. Then I wrote an introduction to a new edition of Mary Wollstonecraft’s Vindication of the Rights of Woman, which felt like a huge achievement.

— So this emptiness, this absence was real. It wasn’t a choice for your writing, it was really impossible for you to have a time for work, a time for studying, a time for research, but at the same time you saw your colleagues occasionally?

Oh yes, I couldn’t even read a book. I don’t mean a scholarly work. In the daytime, most of the time I could not read at all, and that was a terrible deprivation. The feelings inside me just made it impossible to follow a line of print and then things would get a little bit easier and I would be able to do so. But of course I maintained my connections with all my friends and I did continue for a while with History Workshop Journal. Even when I was in Friern for the first time, I had some editorial meetings there. It would come and go, I guess, probably more than I remember, and probably in patches of time, in which I could do a bit more again and then it would vanish… That’s what it was like.

— I see and you had the access to the library in Friern?

— Yes, sitting in the lovely old library in Friern, but I didn’t spend much time there. I don’t remember how often I went. It’s just that the memory of sitting there is powerful because it was so unlike the rest of Friern. It looked like a gentlemen’s library from the nineteenth century.

— A very nice Victorian place.

— Exactly, whereas the rest of the hospital was so rundown.

— I saw in this library a sort of turning point for the selfhood side of your work. The library of Friern to me was a little shift away from personal suffering towards the possibility of going back to your work.

— No, it’s a nice idea but it wasn’t like that. It didn’t matter that much. The turning point was much later when I got a letter asking me to write the introduction to the new edition of Mary Wollstonecraft and I was going to throw the letter away as I always did, and I didn’t. I wrote the introduction. That was much later, I think it must have been around the end of 1991, because the new edition was published in 1992 and by then I was living in my own flat, I had a study in which I could work, I had a cat to keep me company, my life was getting back on track.

— Okay, but it was interesting to talk about that because for the reader it’s always different, you know.

— Absolutely, I understand.

— A question about the human relations you experience in the book. We feel that encounters, fellows, new friends, patients who lived with you in Friern, are very important to you and you explain that they were part of your healing too.

— Yes. I want to say two things about this. First of all that there is a real question and it’s an important question about psychoanalytic psychotherapy, which is to do with whether the actual content of interpretations matters as much as the relationship between patient and therapist. I think both are very important but the dynamic between me and the man I call ‘V’ in the book was absolutely fundamental to the changes that occurred in me. At the core of that dynamic was the growing sense of being understood by another human being and the experience of being understood is so profound… I think it’s one of the most profound experiences that we can have, when we know that someone has, in some sense, looked inside us and things that we may not want to have known about at all are understood and accepted for what they are. It’s the process of interpretation that then shows the patient that they have been understood, and so I just want to say for people who are interested in this question of psychoanalysis, I think that interpretation and relationship can’t be separated. Whether the other relationships around me were also part of the healing, yes, I think they were, yes, absolutely. I have had friendships all my life and they were not enough for me. They couldn’t keep me going, they couldn’t effect the sorts of changes in me that were needed, but while I was inside this process of changing, I think that the ways I started to make use of my emotional connections with people began to change, and I was able then to draw more from those relationships, to give more, which of course is part of being able to take more, and to feel connections with people in ways that I had not done before. So, having people around me, friends – so many of my friends were wonderful in the support they gave me – or people in the hospital, in the day centres where I could give forms of support to them, receive from them… Those things, I think, were very, very important to me. I don’t want to romanticize them. For people with very serious mental illnesses connecting up is difficult and faces a lot of limitations, but having these forms of companionship and feeling my own emotional resources being called upon with my friend whom I call Magda in the book, being able to give something to her in the way of help and support but without any illusions that I was making any difference to her underlying condition, which I was not, and her presence there being important to me… So, yes, these things mattered a great deal.

— Is there a connection with your 2009 book On Kindness in what we are saying now? You wrote this book with a psychoanalyst.

— Adam Phillips, a psychoanalyst, yes.

— And the title is On Kindness. Is there some connection with this process you’re talking about?

— Yes, absolutely. The wish to write the book was driven by these experiences and it was something that Adam, who has published many books, was thinking about; and it is his book as well. Those experiences also drive my current research which is on the history of solitude, because I describe in the book that for some years I wasn’t able to be on my own, that I though being alone would kill me… and that was a terrible experience. I have since discovered that is not an experience confined to people with serious mental illnesses. The capacity for solitude is something that varies a great deal in people but also has this fantastically rich history.

— So you are preparing something about that?

— Yes, I am working on a book about solitude. I am not entirely sure what shape the book is going to take yet, but I have published one essay and another one has come out, and I am thinking about whether to confine it to the eighteenth century, which is my principal area of historical work, or to broaden it out. I am trying to decide these things.

— Thank you, Barbara.

— It has been a pleasure.