In 1984, in his work Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies1, John W. Kingdon introduced the concept of “window of opportunity”. Today, it is widely used in political science to explain the implementation of public policies. Only recently has it been increasingly applied in history, as have other notions from public policy analysis, such as “framing” and “instrument”2. This transdisciplinary use goes hand in hand with the still largely utilitarian use of borrowed notions and is very seldom accompanied by a reflective approach. This article, written by researchers specialised in urban history and in the sociology of public policy, in contrast seeks to put into practice the concept of window of opportunity with the goal of enriching historical debate and adding complexity to the notion, in light of new empirical data on housing policies in Paris during World War II, treated from a historical point of view3.

The aim here is not to present Kingdon’s model in detail, but simply to highlight some of aspects of it that, in our view, can be contextualised through the case study that follows below. First of all, although Kingdon’s approach does not deny the importance of cognitive and strategic factors, it places the notion of opportunity at the core of the process. Secondly, opportunity emerges at the intersection of three streams: the problem stream, the stream of various solutions offered by public policy entrepreneurs, and the political stream, composed of several aspects of political life such as elections, changes in administrative organisation, public opinion and pressure groups. The opportunity can be seized when these three streams are in sync. In this model, social actors, called “policy entrepreneurs”, play a central role. The concept of window of opportunity was, as the foregoing suggests, developed to analyse phenomena in a democratic context.

Analysing the housing policies in Paris during the Second World War offers, firstly, an occasion to apply the concept to a situation involving an authoritarian regime and, secondly, to examine the role of policy entrepreneurs further, particularly in a case in which they are members of an administration. During this period, the case of Paris was characterised by a specific power relationship between policy-makers and administration. Indeed, it was the government-appointed Prefect of the Seine that governed the capital city, and Paris did not enjoy truly autonomous political representation. The city council only met to discuss matters that the Prefect had submitted to it, and city councillors were elected by neighbourhood, which ensured their relative apoliticism4. Public policies were therefore implemented in Paris under the aegis of the all-powerful prefectural administration.

The relevance of applying the notion of opportunity appeared to us during the first phase of our research on city planning in Paris between 1940 and 1944. Our aim was to understand the implementation of an urban planning decision in 1941 relating to an insalubrious area, a set of blocks called Îlot 16, located in the fourth arrondissement, at a time when a shortage of building materials and the German occupation might make this decision seem as unrealistic to current-day observers as it did to several commenters at the time5. The idea of a windfall effect came to us. In 1941, an operation that had been envisaged for more than twenty years thus came into being as a result of the persecution of Jews during the same period, which represented a windfall for both the prefectural administration and architects. When the first groups of Jews in Paris were rounded up and sent to concentration camps, their flats were “vacated”. Compensation and rehousing procedures were denied to these absent Jewish tenants (the prefecture overestimated number of them in the neighbourhood) and, elsewhere in Paris, dwellings inhabited by Jewish families gradually became “vacant” and therefore available to rehouse non-Jewish people evicted from Îlot 16. The notion of a windfall effect allowed us firstly to determine the complex links between urban management policies and measures to persecute Jews: neither totally independent, nor was the former a mere by-product of the latter. This first phase of our research helped to reveal a broader intrinsic link between housing policies and anti-Semitic policies, in particular through the discovery of hitherto untapped archival collections. In particular, we found a thread connecting resettled people who had been evicted from Îlot 16 with an empty stock of flats at the disposal of the Seine Prefecture to meet the needs of other population groups. This empirical discovery led us to work further on a theoretical approach to the observed phenomenon and therefore to take seriously the notion of opportunity and the possible associated moral, or rather amoral, implications for some people.

The expelled from insalubre island N° 16 are looking for "Jewish apartments" to relocate,16 September 1943.

Various studies on the confiscation of Jewish property have shown the active involvement of local administrations in seizing persecuted Jews’ assets and the material gain obtained from redistributing them to the population. Only a handful of studies on the Reich have tried to describe such participation and motives, which lie at the intersection of ideological factors and material pressures.

In looking at the Reich’s Ministry of Finance, the Wehrmacht and the families of German soldiers as regards the plundering of Europe, in particular the confiscation of European Jews’ property, Götz Aly has highlighted the financial and material motivations for the Holocaust, the societal dimension of the Nazi State and the way in which wealth obtained through the extermination of the Jews constituted an important factor in the German population’s acceptance of the persecution programme6. Aly concentrated mainly on the inhabitants of the Reich, however, without focusing his analysis on the administrations and populations in German-occupied territories.

The bombing of the St-Denis plain, Porte de la Chapelle, in the North of Paris, on 21-22 April 1944, which left 438 dead and 2,000 wounded, and that of Renault's workshops in St-Ouen, near Paris, on 24 April 1944.

The case of Vienna has provided material for various studies on the policies and procedures for reallocating rental units, in both the public and private housing stock. In 1975, in his pioneering study, Gerhard Botz looked at how, after the Anschluss in 1938, the non-Jewish population of the city seized the rehousing possibilities offered by the persecution of the Jews. He revealed how this process was directed by the National Socialist German Workers’ Party (Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei – NSDAP) and then the municipal housing office. Between March 1939 and March 1940, with the authorisation of the Reich Commissioner for the Reunification of Austria with the German Reich, the office reallocated 8,000 flats. Botz showed that this procedure, more than merely putting into order the uncontrolled plundering that was taking place, a reading that has been advanced to justify it, constituted rather a social policy for the benefit of non-Jews at a time when the construction of municipal housing units had been suspended. Botz spoke of “negative social policy” insofar as, like other social promises by the Nazis, it emerged as a by-product of anti-Semitic policies7.

A real market is created and the postulants seek to get closer to their work, March 23, 1944.

In the Federal Republic of Germany, a question has been debated in historiography for decades, namely the role of material gain, particularly as regards housing, as a motivating force in the massive deportation of German Jews starting in 19418. In this connection, Susanne Willems has analysed the activities of architect Albert Speer’s office, when he was in charge of urban developments and designs in Berlin9. She has shown how the office itself introduced measures to persecute Jews, in particular by evicting Jewish tenants to rehouse families displaced because of demolitions in the centre of the city. Evictions were adjusted to the need to resettle “clients” selected by the office. From late 1941, evictions were coordinated to coincide with deportations. Speer himself took part in decisions about withdrawing protection for Jewish tenants (in 1939) and he implemented evictions. Willems has thus revealed coordinated social and urban engineering and established a strong correlation between the persecution of Jews and urban development.

In other German or occupied cities, local studies have shed light on the rehousing possibilities opened up by the deportation of Jews and implemented by municipalities: the rehousing of evicted families in Munich, families displaced by bombings in Hamburg and Münster, German civil servants and non-Jewish inhabitants of ghettos in German-occupied territories in the East10.

The General Commissariat for Jewish Affairs served as an intermediary for the launching of the transfer of the apartments. And the subject of the letter indicates that the dispossession of Jewish tenants became an administrative category as such, July 15, 1943.

In France, comparable mechanisms have sometimes been revealed in local monographs on the persecution of Jews11. Our research into the situation in Paris allows for a fresh examination of the motives of the administration and the population in the persecution of Jews. Such comparisons illustrate Kingdon’s two points of departure for the idea of opportunity: firstly, public problems do not exist by themselves and, secondly, they can give rise to many types of constructions as solutions.

The prefectural policy to reallocate the flats of Jewish families, and the office on Rue Pernelle

Between the spring of 1943 and August 1944, the brand new "accommodation office" of the Seine Prefecture reallocated the empty flats of several thousand Jewish families in the département. It selected new tenants and imposed these choices onto the owners and building managers of private housing units and low-cost housing associations. During the summer of 1944, it partially delegated this task to city councils in the arrondissements of Paris and other municipalities in the département.

The managers of the building acted as intermediaries for the reassignment of the apartments. Their zeal was obvious: they were in contact with the German service DW which was in charge of emptying the apartments and knew that the appointment of a temporary administrator was necessary to terminate the lease of the former tenant, March 31, 1944.

The genesis of this rehousing policy has not been completely elucidated. At this point in our research, we have identified contributing factors at the end of 1942. Firstly, various decision-makers came together: the prefectural departments, the occupation authorities and the General Commissariat for Jewish Affairs (Commissariat général aux questions juives), a French organisation in charge of the persecution of the Jews and the forced transfer of their property to non-Jews (“Aryanisation”). Secondly, in Paris, landlords who were keen to continue receiving rent money made requests, as did people seeking accommodation for diverse reasons14. By stages and by trial and error, the prefecture matched housing requests with what they perceived to be a housing offer.

It would thus seem that, by the end of 1942, a precedent had been created through the resettlement of people evicted from the insalubrious Îlot 16 in vacant Jewish homes15. This example demonstrates our aforementioned observation about the plurality of ways in which the same opportunity can be seized to solve the same political problem. The case of Îlot 16 institutionalised this opportunity, as it were, by providing a solution for several situations that was eventually turned into a tool to make public policy, not just a way to solve a political problem. This process of stage-by-stage institutionalisation highlights the driving role, not of policy entrepreneurs outside the administration (e.g. pressure groups), but rather the role of a set of administrative players who came together to offer a joint solution for different social groups: people evicted from Îlot 16, landlords and property managers, those displaced by bombings, and non-Jewish families whose dwellings had been requisitioned by the Kommandantur of Paris, mainly in the chic neighbourhoods16. Similarly, the bombing of Boulogne-Billancourt, the home of the Renault factories, on 4 April 1943, resulting in the destruction of more than 1,200 housing units, was not the first in the Paris area, but it sparked a large-scale prefectural rehousing effort. While assistance to displaced people until then focused essentially on emergency accommodation, evacuation and financial aid in the spring of 1943, the prefecture took the initiative to rehouse displaced people from that municipality definitively, more precisely, in Jewish flats. In many cases, the opportunity also satisfied a need to maintain the support of those benefiting from this public policy in Vichy at a time when the tides of military operations were turning in the Allied powers’ favour.

The Housing Department (service de l’Habitation), under the Economic and Social Affairs Directorate at the Seine Prefecture, created an internal fourth section, called the Accommodation Office (service du Logement), which was set up at 2 Rue Pernelle in Paris. Its main mission was, until August 1944, to rent out the flats “left” vacant in the département by Jews who had already been arrested or fled. These flats made up a circumscription by themselves, cutting across all other municipal and sectorial categories (e.g. private/public, low-income/high-end housing). Various citizens and administrative departments sent correspondence to the “Office for Israelite Premises” on Rue Pernelle, an administrative entity that did not officially exist but which took root in the letters of applicants hoping to take advantage of the occasion.

The bombing of Boulogne-Billancourt, in March 1943 and April 1944.

Choosing flats inhabited by exiled or deported Jews can be explained by several factors. In 1942, the non-Jews who had fled the capital in the summer of 1940 in a mass exodus had, for the most part, returned17. Jewish households therefore made up the main category of residents who had been absent for a long time. After the Vel d’Hiv round-up on 16 July 1942, the number of homes abandoned by Jewish families grew. Importantly, most of these flats had been, or were being, looted of their furniture by the occupation authorities. The Western Department (Dienststelle Westen) of the Reichsleiter Rosenberg Taskforce (Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg) organised the massive looting of French Jews’ furnishings in order to send them to Germany18. Nearly 40,000 Parisian flats held by Jews were entirely emptied between 1942 and 194419. Yet the occupation authorities were not interested in all the flats whose furniture they confiscated, even in the chic neighbourhoods. These were the flats that the office on Rue Pernelle reassigned to applicants. The fact that the former tenants had been identified as Jewish was not the justification for the reallocation procedure, but rather “removal by the occupation authorities” and the availability of the flats. The extensive correspondence between the Seine Prefecture and the occupation authorities attests to this administrative hierarchy, which was scrupulously respected, and the intertwining interests of the French administration and the German army.

The choice of these flats may reflect a merely managerial logic, supported by the fact that a certain category of flats was vacant. It can, however, be argued that renting out the flats to others placed the Seine Prefecture in a line of action continuous with the anti-Semitic legislation in effect. That decision confirmed the idea that the Jews would not return and erased evidence of their presence in Paris, thus adding new forms of violence to those already imposed on them by the authorities responsible for their persecution (plundering, arresting, deporting, etc.). Moreover, the choice of these flats in particular stemmed not only from the fact that they were empty: in June 1944, the Prefect made a point of reminding the city councils and departments that “flats whose occupants are war prisoners, workers in Germany, civil servants who have been withdrawn, or people who have been evacuated outside Paris within the last six months” were to be exempted20. Setting the procedure into motion also created a market and social relationships that in turn accelerated and legitimized the looting of flats. The administration itself was a driving force behind the seizing of opportunity, and its housing practices institutionalised a new public policy that, as we shall see below, created a new category of policy entrepreneurs: the beneficiaries of this availability of “Jewish flats”.

Was this re-leasing of Jewish apartments the result of anti-Semitic ideology? It should be emphasised that it was not accompanied by a formalised ideological discourse. The Seine Prefecture produced no other arguments supporting this policy than the proper management of available rental assets and a population looking for housing. The difference with the Aryanisation of Jewish property or the looting of flats is major: racial rhetoric was used to justify both.

The service of Pernelle street could only reallocate apartments on lists drawn up by the German authorities. The latter also recommended future tenants, as in the case of housing no. 4 for which the FeldKommandantur intervened, 14 August 1944.

Here too, we put forward the hypothesis of a windfall effect rendering possible a managerial opportunity in the shadow of the anti-Semitism of the occupation authorities and Vichy. Several facts support this hypothesis. For example, the armistice agreement provided that the French government would pay compensation in the event of German requisition: half to the evicted tenant, and half to the property owner. In the case of already vacated Jewish flats, however, the administration did not have to indemnify the tenant. In a meeting on 21 April 1942, the requisitions advisory committee decided to suspend the payment of compensation for the requisition of the Kahn and Salomon families’ flats located at 195 Boulevard Malesherbes (second and sixth floors) after 25 June 1940. These tenants were deemed “defaulting” and would have to make any request personally21. There was thus an obvious advantage to having Jewish flats available for reallocation. A window of opportunity had clearly been created by the persecutions: a decree on 27 September 1940 banned Jewish families in the free zone from re-entering the occupied zone, and the Germans’ looting of flats triggered legal and administrative eviction procedures to terminate the previous lease and allow the dwellings to be lawfully rented out again. Such discrimination against Jewish people opened up the possibility of confiscating their homes, and this window of opportunity – compared with the one highlighted in the case of Îlot 16 – reveals more concrete measures imposed by the Germans such as the prohibition to circulate and the looting of flats. Any advantages that the prefectural administration could gain from the persecution measures depended on practical decisions by the occupying forces, in particular in terms of time. Indeed, sometimes the prefecture had to wait several months for a flat to be emptied of its furnishings before it could be rented out again.

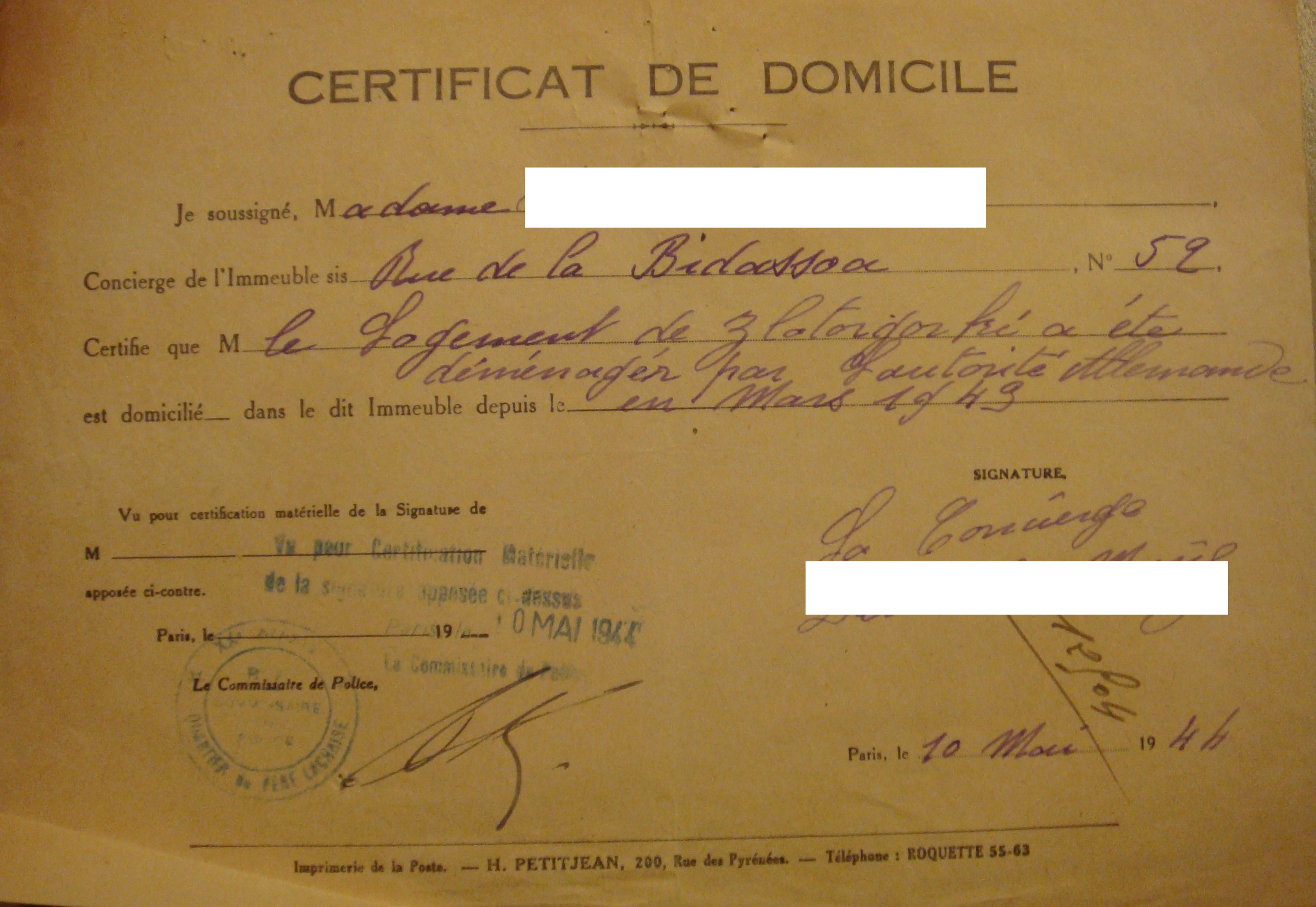

The managers of the building were part of the information circuit that contributed to the functionning of the housing market and the residence certificate forms were diverted from their original function, May 10, 1944.

The case study

In the archival collections that we consulted, the files relating to re-letting procedures are very scattered and are never identified as such, with the vocabulary of the catalogues serving as a smokescreen. In the Archives of Paris, the collection containing individual rehousing files is stored under the name “requisition files for vacant dwellings for the benefit of individuals, filed in alphabetical order, 1942-1944”22. We should point out that it was while trying to find out whether the residents of Îlot 16 were mentioned in these files that we happened upon the thread of empirical data providing the material for the present study. The vagueness of the catalogues is conductive to “good finds” and discoveries. The prefecture had provisionally requisitioned a certain number of vacant premises, mainly “Jewish” ones, to rehouse displaced residents. The public policy analysed here cannot be reduced to those minor requisitions, however. The legal language of requisitions was used in summary tables showing the affected flats, which were established well after the prefecture’s actions. The Jewish holders of terminated lease agreements were designated as “providers” – a term never used between 1943 and 1944 when the operations took place – and rehoused people were described as “beneficiaries”. In the archives of the General Commissariat for Jewish Affairs at the National Archives in Pierrefitte-sur-Seine, the documents that are relevant to our study are stored in a few cardboard boxes with miscellaneous contents belonging to the unit in charge of Aryanising Jewish properties23. In the municipal archives of Boulogne-Billancourt, documents related to the forced transfer of the flats of Jewish families can be found in files on the assistance to refugees and bombing victims24. Filed under “requisitions”, “Aryanisation”, and “assistance to bombing victims”, the rehousing policy in favour of non-Jews was fragmented through an archival classification system based on categories of action already unearthed by historiography. Our research must therefore reshuffle the records, so to speak, in order to flesh out and describe this specific policy.

This situation can be explained by several factors. It was unusual for the French administration to intervene in the sphere of private housing, and administrative restructuring after the war scattered the archival collections. We primarily interpret this situation as being a consequence of the opportunistic dynamics at the very heart of the administration. Indeed, the policy we are studying emerged in the shadow of other policies. After the war, the fact that re-leasing authorisations were relabelled requisitions raises several questions, in particular legal, to which answers must be found.

Our study fans out in several directions which, in light of the foregoing, must take into consideration the post-war period including the perception of these operations after the liberation of France, their legal treatment, the purging of prefecture staff and so forth. One of our main lines of inquiry entails studying the social relationships forged through the reallocation of flats. Each rehousing request file involved a set of stakeholders, with an applicant, various prefectural departments, property managers, owners, caretakers, as well as the Kommandantur, the Dienststelle Westen, and so forth. The recurrence of specific scenarios and individual correspondence, always drawing on the specificity of the person’s situation, analysed as a whole, offers the occasion to understand relationships between Jews and non-Jews, between the population of Paris and the prefectural administration. These prisms have a magnifying effect on the tangled social relationships in an anti-Semitic context. What was the spatial, as well as mental and linguistic, map of these social relationships linked through rehousing requests? What “ordinary” connections to anti-Semitic policies did the various participants have?

All means were used to move into a "Jewish apartment". Joseph Morganti, a postman, wrote to the German authorities (May 8, 1944), and was then recommended by the vice-president of the Paris city council (May 13, 1944), who was told that he could move to Rue des Carreaux when the occupying authorities have put the apartment on market (May 23, 1944). On the other hand, the Bld Ornano dwelling was invested by the janitor of the building, another neighborhood scenario in the reassignment.

In addition, thanks to an examination of German archives25, our analysis of the relationships forged with the occupying authorities and the latter’s perspective on the property transfers, will pave the way for comparisons with other cities, in France and elsewhere. We shall also raise the question of the spread of “Nazi-style” municipal practices beyond the Reich, where we know that such transfers were commonplace26. The issue of how opportunity was consolidated over time and its possible geographical transfer will also be documented, breaking with the largely situational approach of Kingdon’s model and thus enriching discussion about the dynamics of opportunity as applied to the genesis of public policies.

Opportunity in practice: The first data and figures

At the Archives of Paris, we have thus far carefully gone through three-quarters of the collection (Pérotin 901/62/1), which contains files related to rehousing. The first stage involved simply counting and locating the addresses for the rehousing authorisations, which led us to our first observations. We estimate that this archival collection accounts for the re-renting of around 9,000 “vacant” flats. Among them, only 6,000 cases of re-leasing orchestrated by the prefecture were actually processed, and a few dozen by the city councils. We strongly believe, however, that the archival collection in question does not cover all of the administrative procedures analysed. Other archival discoveries will undoubtedly enable us to go further in our study.

The authorization of relocation of the flat situated at 175 rue du Temple, 14 January 1944.

In chronological terms, the phenomenon gathered continuous momentum from the summer of 1943 until the spring of 1944, when it peaked: nearly half of the processed authorisations were issued between March and June 1944. At the end of April 1944, bombing victims, displaced from Noisy-le-Sec and La Chapelle benefited from this acceleration: among the 20,000 families that lost their home in the bombings of the Paris region, we have already identified 800 cases of rehousing. The later decrease in the number of re-let flats can be explained by the fact that the implementation of the procedure was delegated to the city councils, the effect of which is poorly documented in this particular archival collection.

Who were the rehoused people? One per cent of the authorisations were granted to families who were already living on-site. In other words, the landlords had not waited for the prefecture’s permission before renting out the flats again. Half of the beneficiaries named by the prefecture were considered to be bombing victims. They are not representative of the whole Paris area. Four large bombed-out areas account for three quarters of the victims who were rehoused in the flats of Jewish families: Courbevoie and the Gennevilliers peninsula (30 % of those who were rehoused), the neighbourhood of La Chapelle in Paris and the municipalities of Saint-Denis and Saint-Ouen (25 %), Boulogne-Billancourt and Porte de Saint-Cloud (13 %), and Noisy-le-Sec (12 %). The existence of different areas of origin for the displaced people must be examined in terms of chronology, knowledge networks and proximity. For example, the town council of Noisy-le-Sec, itself displaced in April 1944, was moved to Rue Sorbier in the 20th arrondissement of Paris, which seemed to favour the rehousing of its residents in this neighbourhood beginning at that time.

Le pillage des appartements juifs à Paris sous l'occupation

La conférence d'Isabelle Backouche et Sahah Gensburger aux Archives nationales à Paris, en 2015.

Families whose dwellings were requisitioned were, in the end, not very well represented in the sample (5%), but this fact may be explained by poor documentation during the first few months of the procedure27. Half of them were evicted by the occupation authorities, in particular from Avenue de la Bourdonnais and from barracks such as the one in Place de la République. A third of the families were evicted by the French authorities, in particular from the insalubrious Îlot 16 and from the demilitarised zone surrounding the city of Paris, which had been the object of large-scale demolition operations beginning in 194128. When our examination of archives has been completed, a comparison between the timeline for the implementation of the procedure and the reallocation of the flats in question will provide much information for understanding the fate of the Jewish community in Paris. We shall be able to fine-tune our analysis of the strategies of Parisian Jews for hiding and survival, and to pinpoint the gradual decrease in their numbers within a more precise chronology.

The form sent by the Prefecture of the Seine to the flat owners in Paris to declare the vacancy of the apartments of their former Jewish tenants in the spring of 1944.

As in Munich, however, there was a large gap between the prominence given to this rehousing operation and the social categories of people who were actually rehoused29. In Paris, more than a third of the authorisations were granted to families who were named by the Kommandantur or the Dienststelle Westen, which reflects a little-known closeness between the German authorities and the Parisians who visited their offices and sought appointments with them. Another scenario involves nearly 10% of the files, which contain a letter of recommendation from an influential French person (e.g. the director of a large company; Pierre Taittinger, President of the City Council of Paris; and city councillors such as Maurice Levillain). The large number of players involved in these various exchanges reflects the level of publicity that the procedure enjoyed, largely forgotten today.

The locations of the rehousing addresses reveal a high concentration in Paris proper, with only 1% of flats located outside Paris (mainly in Clichy, Montreuil, Neuilly-sur-Seine, etc.). Yet we know that around a quarter of the Jews in the Seine département were living in the suburbs30. Several hypotheses must be considered to explain the situation, in particular regarding the extent to which the procedure was concentrated in rental units and did not concern owner-occupied houses, which were largely represented in the Paris suburbs. The social relationships created around the transfers might explain this concentration (e.g. closeness between Parisian landlords and the prefecture, neighbourhood-related factors). Above all, in a context characterised by the bombing of the suburbs and by the widespread belief that Paris would not be bombed, a major inflow of people into inner Paris can be observed. Suburbanites who made requests mostly asked to be resettled in Paris. In contrast, bombed-out municipalities, such as Boulogne-Billancourt, deemed it inopportune to rehouse their displaced residents on their territory31. Whatever the explanations may have been, this large-scale reallocation of properties resulted in a massive influx of suburbanites into Paris.

In Paris, the geographical breakdown of housing locations also shows, in a quantitative way, the Jewish population’s places of residence at the beginning of the 1940s. An expected concentration in the northern and eastern arrondissements of Paris can be seen, which correlates, however, with average population densities in general. It can also be observed a larger share of addresses in the 16th and 17th arrondissements and the left bank than among those who were registered in the Drancy internment camp. Yet, since part of the Paris police’s census report on Jews was destroyed, these Jewish residents only appear on the lists of the Paris Shoah Memorial and its historical maps. Our research shall examine the status of these different addresses – shedding light on how Jewish families moved around to avoid being arrested – and compare them with the current map of Jewish presence in Paris. Lastly, these residential movements call into question an approach that, when developing tools to understand the Jewish population of Paris, only takes into account sources produced by anti-Semitic policies, an approach whose limitations are demonstrated by our study32.

Concentrating on the dynamics of opportunity as regards to the implementation of housing policy has produced several results in terms of knowledge. First of all, this approach has confirmed the importance of not limiting oneself to an emphasis on ideological factors when analysing the persecution of the Jews during World War II. Secondly, conducting research on a topic in the context of an authoritarian regime highlights the fact that, while the opportunity made possible by a junction of streams − the window as defined by Kingdon − must effectively be seized by stakeholders, they can very easily be members of the administration. Such “opportunistic” public policies, from an administrative point of view, lead to the creation of new social players who, as soon as the context changes, are likely to establish themselves, in turn, as policy entrepreneurs in order to solve a new problem. In the case at hand, after the liberation of Paris, a proportion of Jews from the Seine département returned from hiding and, to a much smaller extent, from concentration camps. With the issue of housing having vanished from national priorities beginning in 194833, however, tenants who had been rehoused in Jewish flats, called “tenants acting in good faith” at the time, established themselves as stakeholders. They asserted what they deemed to be their rights, created in a window of opportunity that the defeat of the Reich then definitively shut. The intersecting of urban history and Holocaust history makes the city a prime spot for analysing all the stakeholders operating in a sought-after and shared area, albeit damaged by bombing. The city, as the issue of housing, is an ideal focale from which observing the social interactions giving rise to opportunities. Historical inquiry enriches the political scientist’s toolbox, and our research has not only benefited from interdisciplinary dialogue, it has also expanded it, attesting to the interactivity of the social sciences.

Notes

1

John W. Kingdon, Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies, Little, Brown and Co, Boston, 1984.

2

Christophe Capuano, Vichy et la Famille. Réalités et faux semblants d’une politique publique, Rennes, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2009 and Sébastien Ledoux, Le devoir de mémoire. Une formule et son histoire, Paris, CNRS Éditions, 2016, to cite only a couple of examples.

3

The interest of studying the administrative apparatus of the French state in order to advance the analysis of public policies has already been demonstrated by Wolfgang Seibel, “A Market for Mass Crime? Inter-institutional Competition and the Initiation of the Holocaust in France, 1940−1942”, International Journal of Organization Theory and Behavior, vol. 5, no. 3 & 4, 2002, pp. 219−257.

4

A law on 16 October 1941 stipulated that, from then on, city councillors would be appointed rather than elected, according to Philippe Nivet, “L’histoire des institutions parisiennes d’Etienne Marcel à Bertrand Delanoë” Pouvoirs, no. 110, September 2004, pp. 5−18.

5

Isabelle Backouche and Sarah Gensburger, “Expulser les habitants de l’îlot 16 à Paris à partir de 1941 : un effet d’‘aubaine’?”, in Tal Bruttmann, Ivan Ermakoff, Nicolas Mariot, Claire Zalc (dir.), Pour une microhistoire de la Shoah, Genre humain, Paris, Le Seuil, no. 52, 2012, pp. 169−19; Isabelle Backouche, Paris transformé. Le Marais, 1900−1980 : de l’îlot insalubre au secteur sauvegardé, Grane, Créaphis, 2016, pp. 72−73.

6

Götz Aly, Hitler’s beneficiaries: Plunder, racial war, and the Nazi welfare state, New York, Metropolitan Books, 2007.

7

Gerhard Botz, Wohnungspolitik und Judendeportation in Wien 1938 bis 1945: Zur Funktion des Antisemitismus als Ersatz nationalsozialistischer Sozialpolitik, Wien/Salzburg, Geyer, 1975.

8

This historiography begins with Hans Günther Adler, Der verwaltete Mensch. Studien zur Deportation der Juden aus Deutschland, Tübingen, Mohr, 1974 (chapter “Bewegliche Habe und Wohnung”, pp. 606−611).

9

Susanne Willems, Der entsiedelte Jude. Albert Speers Wohnungsmarktpolitik für den Berliner Hauptstadtbau, Berlin, Hentrich, 2002.

10

All these categories can be found in Riga, a German-occupied soviet city. A study on this city is currently being conducted by Eric Le Bourhis, one of the co-authors of this text. It sheds light on the involvement of the municipality in reallocating the flats of Jewish families in the early days of the German occupation of the city.

11

Nicolas Mariot and Claire Zalc, Face à la persécution. 991 Juifs dans la guerre, Paris, Odile Jacob, 2010; Shannon L. Fogg, “Everything Had Ended and Everything was Beginning Again’: The Public Politics of Rebuilding Private Homes in Postwar Paris”, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 2014, vol. 28, no 1, pp. 277−307.

12

Archives of Paris (AP), Perotin collection (901/62/1).

13

Archives of the Ministry of Defence (Service historique de la Défense − SHD), GR 9R 641, minutes from a meeting of the Central Service for Property Requisitions at the French Ministry of War on 22 December 1944.

14

For example: AP, 1397W 184, letter from the Paris public housing agency (Régie Immobilière de la Ville de Paris) to the Housing Department of the prefecture dated 4 September 1942; AN, AJ38 815, letter from René Fontaine, building manager at 11 Rue de Turin in Paris, to police headquarters, dated 26 September 1942; Contemporary Jewish Documentation Centre (Centre de documentation juive contemporaine − CDJC), 193 160, letter from J. Marlhens, property manager, to the General Commissariat for Jewish Affairs, dated 7 December 1942.

15

AP, Perotin collection 6096/70/1 753, letter from the Director of Requisition and Occupation Affairs, 19 November 1942. He indicates that the General Commissariat for Jewish Affairs and the special unit at police headquarters let him know that the request was within the exclusive remit of the occupation authorities.

16

AP, Perotin collection 6096/70/1 753, report of visit, 8 December 1942.

17

Hanna Diamond, Fleeing Hitler: France 1940, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2007.

18

It was also the same Seine Prefecture that was entrusted with the logistical management of the Drancy internment camp upon its opening, according to Michel Laffitte and Annette Wieviorka, À l’intérieur du camp de Drancy, Paris, Perrin, 2012.

19

Sarah Gensburger, Images d’un pillage. Album de la spoliation des Juifs à Paris, Paris, Textuel, 2010 [Witnessing the robbing of the Jews: A photographic album, Paris, 1940−1944, translated by Jonathan Hensher with the collaboration of Elisabeth Fourmont, Bloomington, Indiana University Press, 2015] and, with Jean-Marc Dreyfus, Des camps dans Paris. Austerlitz, Lévitan, Bassano, Paris, Fayard, 2003.

20

AP, 1106 W 47, order of the Prefect of the Seine, 8 June 1944.

21

AP, Perotin collection 6096/70/1, box no. 799.

22

AP, Perotin collection 901/62/1.

23

For example, AJ38 2692: inventory of Jewish flats that were rented out again to displaced people designated by the Seine Prefecture or the police headquarters.

24

Municipal Archives of Boulogne-Billancourt (AMBB), 6H 81 “Assistance to refugees and displaced persons”.

25

Bundesarchiv-Lichterfelde, collection NS 30 (Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg); Bundesarchiv-Freiburg, collection RW 35 (Militärbefehlshaber Frankreich).

26

Wolf Gruner, “The German Council of Municipalities (Deutscher Gemeindetag) and the Coordination of Anti-Jewish Local Politics in the Nazi State”, Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 1999, 13 (2), pp. 171−199.

27

Bias that we may be able to correct by analysing the files of the General Commissariat for Jewish Affairs (AN, AJ38), which provide better documentation.

28

Isabelle Backouche, “Rénover le centre de Paris : quel impact sur les marges ? 1940−1970”, in Florence Bourillon and Annie Fourcaut (dir.), Agrandir Paris, 1860−1970, Paris, Publications de la Sorbonne, 2012, pp. 325−341.

29

A monograph on the persecution of Jews in Munich examined the profiles of new tenants of the flats of the 350 last Jewish families deported from the city in 1941−1942: Ulrike Haerendel, “Der Schutzlosigkeit preisgegeben: Die Zwangsveräusserung jüdischen Immobilienbesitzes und die Vertreibung der Juden aus ihren Wohnungen”, in Angelika Baumann and Andreas Heusler, München arisiert: Entrechtung und Enteignung der Juden in der NS-ZEIT, München, C. H. Beck, 2004, pp. 105−126.

30

Jean Laloum, Les Juifs dans la banlieue parisienne des années 20 aux années 50, Paris, CNRS Editions, 1998.

31

For example: AMBB, 6H 15, letter from the Boulogne-Billancourt town council to the Director of Departmental Affairs in the Ministry of the Interior, 21 January 1944.

33

Frédérique Boucher, “Les planificateurs et le logement, 1942−1952”, Cahiers de l’IHTP, no. 5, June 1987, pp. 83−91.

Bibliographie

Hans Günther Adler, Der verwaltete Mensch. Studien zur Deportation der Juden aus Deutschland, Tübingen, Mohr, 1974.

Götz Aly, Hitler’s Beneficiaries: Plunder, Racial War and the Nazi Welfare State, New York, Metropolitan Books, 2007.

Isabelle Backouche, "Rénover le centre de Paris: quel impact sur les marges ? 1940-1970", in Florence Bourillon, Annie Fourcaut (dir.), Agrandir Paris, 1860-1970, Paris, Publications de la Sorbonne, 2012, p. 325-341.

Isabelle Backouche, Paris transformé. Le Marais, 1900-1980: de l’îlot insalubre au secteur sauvegardé, Grane, Créaphis, 2016, p. 72-73.

Isabelle Backouche, Sarah Gensburger, "Expulser les habitants de l’îlot 16 à Paris à partir de 1941 : un effet d’‘aubaine’?", in Tal Bruttmann, Ivan Ermakoff, Nicolas Mariot, Claire Zalc (dir.), Pour une micro-histoire de la Shoah, Genre humain, Paris, Le Seuil, n° 52, 2012, p. 169-219.

Gerhard Botz, Wohnungspolitik und Judendeportation in Wien 1938 bis 1945: Zur Funktion des Antisemitismus als Ersatz nationalsozialistischer Sozialpolitik, Wien/Salzburg, Geyer, 1975.

Frédérique Boucher, "Les planificateurs et le logement, 1942-1952", Cahiers de l’IHTP, n° 5, juin 1987, p. 83-91.

Christophe Capuano, Vichy et la Famille. Réalités et faux semblants d’une politique publique, Rennes, Presses Universitaires de Rennes, 2009.

Hanna Diamond, Fleeing Hitler. France 1940, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2007.

Jean-Marc Dreyfus, Des camps dans Paris. Austerlitz, Lévitan, Bassano, Paris, Fayard, 2003.

Shannon L. Fogg, "Everything Had Ended and Everything was Beginning Again’: The Public Politics of Rebuilding Private Homes in Postwar Paris", Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 2014, vol. 28, n° 1, p. 277-307.

Sarah Gensburger, Images d’un pillage. Album de la spoliation des Juifs à Paris, Paris, Textuel, 2010.

Wolf Gruner, "The German Council of Municipalities (Deutscher Gemeindetag) and the Coordination of Anti-Jewish Local Politics in the Nazi State", Holocaust and Genocide Studies, 1999, n° 13, vol. 2, p. 171-199.

Ulrike Haerendel, "Der Schutzlosigkeit preisgegeben: Die Zwangsveräusserung jüdischen Immobilienbesitzes und die Vertreibung der Juden aus ihren Wohnungen", in Angelika Baumann, Andreas Heusler, München arisiert: Entrechtung und Enteignung der Juden in der NS-ZEIT, München, C. H. Beck, 2004, p. 105-126.

John W. Kingdon, Agendas, Alternatives and Public Policies, Little, Brown & Co, Boston, 1984.

Michel Laffitte, Annette Wieviorka, À l’intérieur du camp de Drancy, Paris, Perrin, 2012.

Jean Laloum, Les Juifs dans la banlieue parisienne des années 20 aux années 50, Paris, CNRS Editions, 1998.

Sébastien Ledoux, Le Devoir de mémoire. Une formule et son histoire, Paris, CNRS Éditions, 2016.

Nicolas Mariot, Claire Zalc, Face à la persécution. 991 Juifs dans la guerre, Paris, Odile Jacob, 2010

Philippe Nivet, "L’histoire des institutions parisiennes d’Etienne Marcel à Bertrand Delanoë", Pouvoirs, n° 110, 2004, p. 5-18.

Wolfgang Seibel, "A Market for Mass Crime ? Inter-institutional Competition and the Initiation of the Holocaust in France, 1940-1942", International Journal of Organization Theory and Behavior, n° 3-4, 2002, p. 219-257.

Susanne Willems, Der entsiedelte Jude. Albert Speers Wohnungsmarktpolitik für den Berliner Hauptstadtbau, Berlin, Hentrich, 2002.