The facial casts of the anthropology museum in Florence

The particularity of the history of Italian anthropology is that it was constituted as a discipline during the founding of the nation-state. The first chair in anthropology in Italy – and in Europe too – was established in 1869 in Florence, the then capital of the country whose unification had been proclaimed eight years earlier in 1861. Paolo Mantegazza (1831-1910) was appointed to the chair. He had trained as a doctor, but was also a politician, anthropologist, photographer, and founder of the national museum of anthropology (1870)1. He also founded the Italian society of anthropology and ethnology (1870) and its journal Archivio per l’antropologia e l’etnologia (1871).

The founding of the museum was closely bound up with the eclectic thought of Mantegazza, about whom a few words are necessary2. Mantegazza was head of what is known as the Florentine school. He was a contemporary of Charles Darwin, with whom he corresponded, and of Cesare Lombroso (1835-1909), who was initially a friend and colleague of his (both taught medicine in Pavia). Mantegazza embraced evolutionist theories based on the idea of progress3. He thought of anthropology as a “natural history of man”4. To his mind, humanity should be studied “as one sees it and as one touches it”5, “following the same experimental criteria with which one studies plants, animals, and stones […], unburdened by religious traditions or preconceived philosophical theories”6.

The museum was initially housed in cramped premises in the center of Florence on Via Ricasoli, near the botanical gardens. The ethnographic holdings included objects from the old imperial collections of the museum of physics and natural history, several artefacts gathered by James Cook, the famous explorer, during his third expedition in the Pacific (1776-1779), and those brought back by the explorer Carlo Piaggia (1827-1882) from Africa7. As for its anthropological collection, it quite simply did not exist. The Catalogo cronologico del museo nazionale di antropologia di Firenze (chronological catalogue of the national museum of anthropology in Florence) is an essential tool for understanding how its collection was progressively built up. The first items in the catalogue are two skulls from Mantegazza’s personal collection. In 1874, in reaction to this dearth of artefacts, a journal, Archivio per l’antropologia e l’etnologia, appealed “to diplomats, consuls, directors of great trading houses, doctors, and all Italians living in European colonies, to remember this national museum and send it photographs, skulls, skeletons, clothing, weapons, industrial products, information, in short everything they deem relevant for characterizing a population”8. The museum’s collection grew rapidly over the first thirty years thanks in part to these donations, and especially to anthropological missions9.

The first part of the chronological catalogue is dedicated to anthropology, and lists an important collection of skulls and skeletons, together with the remains of mummies, samples of hair, and a collection of plaster casts. The latter include facial casts – the focus here – together with casts of skulls and of fossils10. In common with European anthropological circles generally, Mantegazza based the study of man on measuring bodies, for he held morphological characteristics to reflect an individual’s moral and intellectual qualities. Like his French colleagues, Mantegazza attached key importance to craniometry, of which he was one of the main theoreticians in Italy. That is why the most complete collection held by the museum in Florence is that of skulls. Nevertheless, he eventually distanced himself from this method, stating in 1870: “woe betide us if anthropology is reduced to craniometry; woe betide us if we have no other measurement to classify men than Camper’s facial angle, or Virchow’s sphenoidal angle! The skull is merely the husk of the brain, and the brain in turn an infinite accumulation of still undefined viscera, that we have not yet studied”[2].

Mention needs to be made of Mantegazza’s famous 1876 experiment to expose the largely unscientific nature of craniological studies11. Mantegazza selected 200 skulls from his collection and took the ten most significant measurements. He then mixed up these exemplars and invited two of his friends (one a zoologist, the other an anthropologist) to sort them into two categories: “an upper category and a lower category”. The first was symbolized by “Olympian Zeus” embodying “one of the highest human forms”, in opposition to the second, designated “the prognathic negro or microcephalus pithecoid, [constituting] the lowest and last human echelon”12. The results of this experiment upset all expectations. Among the first category figured the skull of a Polynesian, alongside a few Italians, while the second category included an Italian and Australians. Even the skulls of Florentines – considered as the worthiest representatives of the Italian people – were scattered across the two categories. The skull of the eminent Italian poet Ugo Foscolo was placed a bit higher than that of an illiterate Sardinian, and lower than a beggar from Brescia. Mantegazza laid out the skulls in the order of these results and put them on display for several weeks as a warning against “geometrical metaphysics” and the “esoterics of figures”13.

Disagreements on this subject were probably behind Mantegazza’s disenchantment with Lombroso, a theoretician and fervent advocate of criminal craniometry14. During the 1880s, other European schools of anthropology went through a similar crisis15. In France in particular, the founder of craniometry, Paul Broca, was, surprisingly, the person who “perceived its contradictions and sterility better than most of his contemporaries”16. This growing disinterest for craniometry encouraged scientists to diversify their methods for characterizing “races”17. It was in this context that facial casts came to fore of anthropological practice.

Duplicating, collecting, and hierarchizing humanity: facial casts made from nature

Between 1875 and 1876, the museum moved into larger premises on Via Capponi, and could now house its ethnographic collections, numbering 10,000 items. These were crucial years in the evolution of Mantegazza’s theories. His distrust of skull measurements was accompanied by a growing interest for an aesthetics of morphology. Psychology, and the notions of beauty and pleasure, became central to his studies18. Aesthetics constituted to his mind a genuinely ethical criterion. He went as far as defining man as “an aesthetic molecule”19. “Beauty” and “truth” were one and the same thing in his Platonic approach. This was probably what led him to question the universalist conception of race characterizing his early works. In 1876, in L’uomo e gli uomini, Mantegazza denied the existence of the human species: “species do not exist in nature, only individuals exist. The species is purely and simply a creation of the human brain”. Instead, he celebrated “a universal human brotherhood”. To illustrate this, he employed an elegant botanical metaphor: the branches of the human tree “are so intertwined they resemble an extremely dense bush”20.

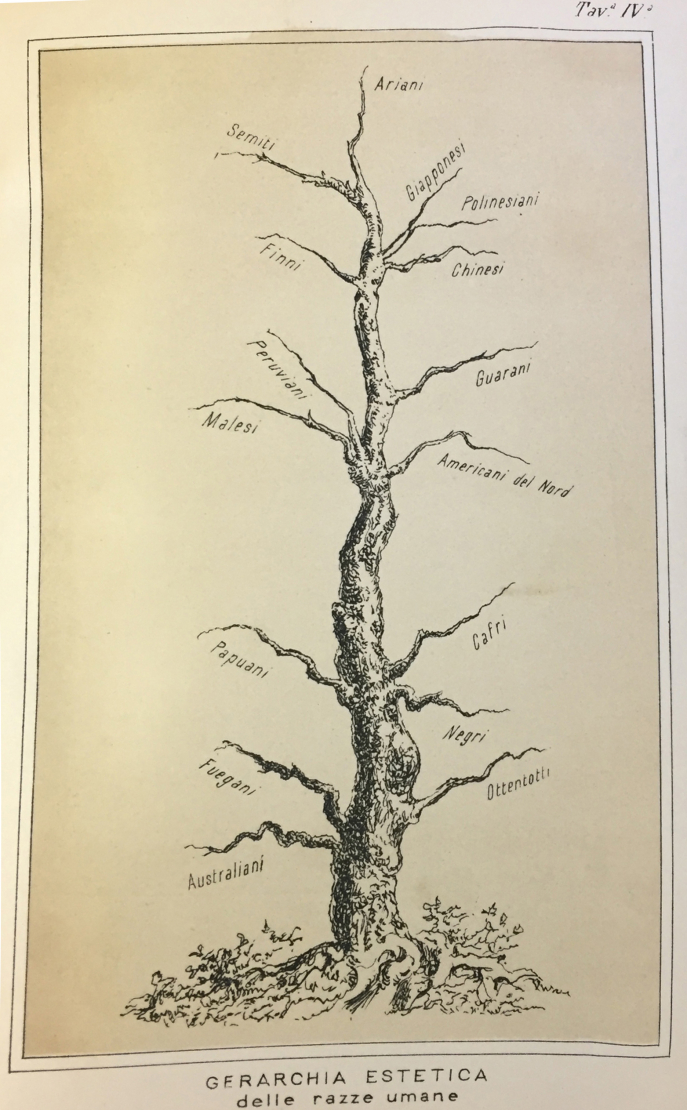

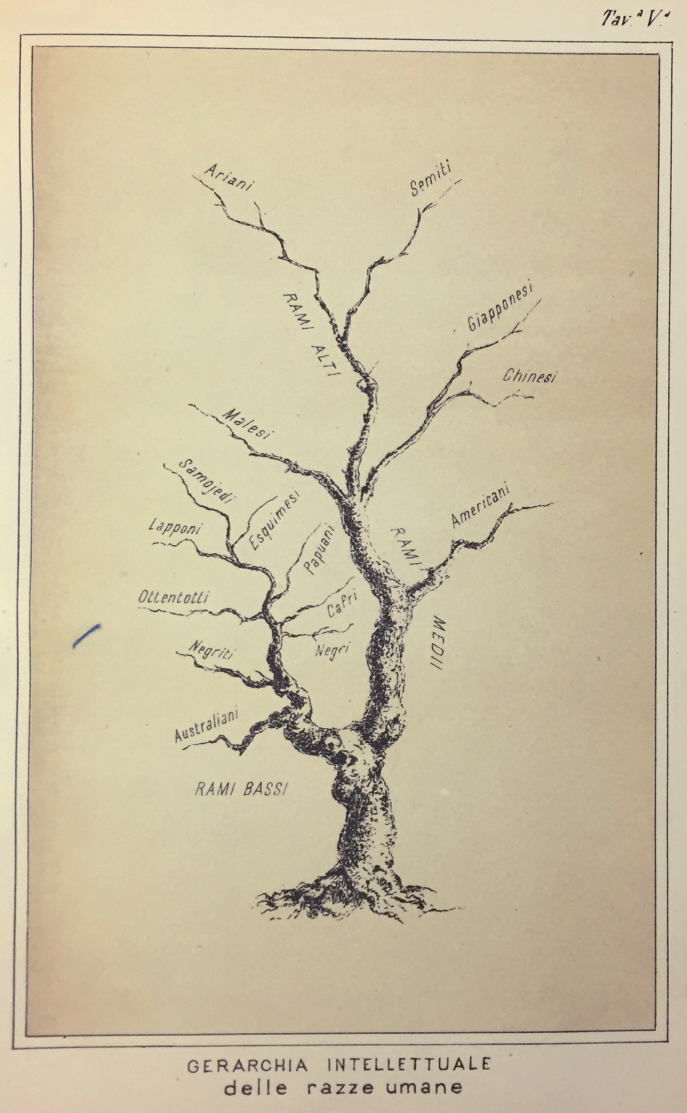

Five years later, in Fisionomia e mimica (1885) – translated into English in 1890 as Physiognomy and Expression – this universalist conception of humanity gave way to a classification of races grounded in the hypothesis that men’s aesthetic characteristics reflected their degree of intelligence. In this work, Mantegazza states: “I firmly believe in a type of beauty, superior to all the secondary types of beauty – Mongolian, American, Negro, etc. – and I always find that when a man of inferior race is exceptionally beautiful he approximates to our Aryan type”21. The dense bush symbolizing humanity is replaced by three “ethnological trees” [fig. 1, 2, 3] illustrating his conception of the aesthetic hierarchy, defined as “a system, a method; and a modus agendi”:

At the foot and at the summit of the tree of humanity, the branches and branchlets approximate, so that the highest and the lowest touch. The negro, who rises to the Caffir, approaches the European, and the European degenerated by goitre, cretinism, or hunger, approaches the Negro and the Australian.22

Paolo Mantegazza, Fisionomia e mimica, Milan, Fratelli Dumolard, 1881,

tav III, IV, V.

This theory, in which aesthetics and physical anthropology coincide, was probably behind Mantegazza’s growing interest for photography and facial casts made from nature. He was one of the pioneers and greatest experts on photography in post-unification Italy, and in 1889 was named president of the Società Fotografica Italiana23. He argued that anthropological photography, freed from the strict limits of anthropometric portraiture, should represent the subject together with its environment. This conception, a forerunner of contemporary documentary photography, was laid out in official instructions sent to travelers and published in Italy by the geologist, anthropologist, and paleontologist Arturo Issel24. Enrico Heyller Giglioli and Mantegazza’s assistant, Arturo Zanetti, wrote the entry for “L’Antropologia e l’Etnologia”, which included the following instructions: “the man should be photographed face-on and in profile […]. This scientific photography needs to be supplemented by an artistic form capable of restituting the natural attitude, almost the character of the individual belonging to a race”25. In accordance with Mantegazza’s teaching, the Florentine school of anthropology used photography as a privileged means of documenting human diversity and comparing individuals26.

While anthropologists were unanimous in welcoming the capacity of photography to reproduce reality, it did not replace plaster casts. This technique was officially legitimized as an anthropological method by Paul Broca in 1865, in his Instructions générales pour les recherches et observations anthropologiques (anatomie et physiologie)27. It is useful to briefly go over the history and issues involved in the practice of anthropological casts. This technique, in use since Roman times (mainly to make funereal masks for votive purposes), was taken up again in the mid-nineteenth century by anthropologists because of its capacity to constitute a document deemed “authentic”. It was first adopted by phrenology, before gradually being used during expeditions. The busts produced by Alexandre Dumoutier (1797-1871) during the final three-year (1837-1840) scientific expedition in the Pacific Ocean led by Jules Dumont d’Urville (1790-1842) is one of the first examples of molds taken on living subjects28.

Lidio Cipriani molding a facial cast on a living individual (1/2)

Lidio Cipriani molding a facial cast on a living individual (2/2)

Casts were made in two stages. The first consisted in taking a mold in situ, while the cast tended to be produced and colored in anthropology laboratories. Making the mold was an invasive technique which obliged individuals to lie on the ground and breathe through a straw for the time needed to place the plaster on the face and for it to set. In most cases this frightened populations, and anthropologists had to negotiate or use force to convince models. Casts do not provide any indications about the bone structure of the bodies, but have other qualities which lent themselves well to the ambition of late-19th-century anthropologists to visually hierarchize humanity. Their effectiveness resides primarily in the realism of the shapes and colorings. The life-size three-dimensional reproduction of individuals’ faces allowed these objects to be moved, exhibited, compared, and studied. They could be reproduced in series, and thus distributed across Europe, making it possible to partake in common debate about the same material, at a time when anthropology was becoming established as a university discipline and devising its first theories.

Mantegazza praised the effectiveness of casts made from living individuals for their capacity to restitute forms “in their entirety”, unlike photography which could only reproduce “certain elements”29. In 1891, he used this technique when two Aka pygmies discovered by the explorer Giovanni Miani passed through Florence,30 an event I return to later on. Mantegazza recognized that his anthropometric measurements of these two individuals were imprecise. For this study he referred to the “photos taken by Mr. Giacomo Brogi, a Florentine photographer, and the plaster casts of Thibaut’s hand and foot, produced by Mr. Giuseppe Felli, modellatore and formatore at the Italian museum of anthropology”,31 deemed to be of greater scientific value.

The original core of the Florentine collection of casts, acquired by Mantegazza in 1885, comprises 154 casts made by the German explorer, naturalist, and ethnologist Otto Finsch (1839-1917) during a three-year (1879-1882) voyage in New Guinea, Polynesia, Australia, and New Zealand32. Finsch thus built up a repertoire of Oceania’s populations. He vaunted its merits in a pamphlet (veering towards advertisement) with the title Gesichtsmasken von Völkertypen der Südsee und dem malayischen Archipel, nach Lebenden abgegossenin den Jahren 1879-1882 (1887)33. This lists the casts with their prices, accompanied by enthusiastic comments by the most eminent contemporary European anthropologists: Rudolf Virchow, the president of the Berlin anthropology society; Armand de Quatrefages, the professor of anthropology at the natural history museum in Paris; Leopold von Schrenk from the St Petersburg academy; William Henry Flower, the director of the British museum for natural history in London, and Adolf Bernard Meyer from Dresden. The pamphlet included a short text in English written by Mantegazza and the vice-president of the Società di antropologia, Enrico H. Giglioli:

Società italiana d’Antropologia, Etnologia e Psicologia comparata :

Firenze, 14, November 1885

The collection of plaster-casts representing different ethnical types of Micronesia, Polynesia, Melanesia, Australia, Papuasia and Malesia, taken from Nature by Dr. Otto Finsch in his travels in the lands bathed by the Pacific-Ocean in the years 1879-82 is a truly and quite unique series of its kind. It has been formed on a strictly scientific method, and enables us to study and compare several races of Mankind hardly known by name in Europe, or scantily represented in one or two museums by a few crania or a few bad photographs.

With the aid of such a collection several of the most intricate problems of the complicated ethnology of that vast region, will be solved. And especially the highly interesting question of the results of the contact and intermixture of Malayan-Negroid (so called Papuan) and Polynesian elements.

What gives moreover a very special value of this collection is the admirable manner (by the skill of Mr. Castan) in which the many and varied shades of color of the skin have been reproduced from life in all these casts.

The collection is a very extensive one; and truly Dr. Finsch is singularly deserving of the highest praise and in successfully conducting so difficult, and sometimes dangerous undertaking, he has rendered a very great service to Science, and earned the gratitude and admiration of all anthropologists.

For us it is indeed not only a duty but a pleasure to sign this testimonial.

Anthropologists were fascinated by Oceania, for it reflected the “paradox of infinite racial complexity within a space unified by common cultural and linguistic features”34. Especially, it fueled a heated debate between monogenists and polygenists for “its immensity seemed to exclude the hypothesis of a population with a unique origin”, and thus to favor theses of multiple origins35. The fact that Mantegazza and Giglioli mention the realism of the skin, reproduced from life, suggests a monogenistic perception of humanity, for skin color makes it possible to observe interbreeding, a central phenomenon in the theory favoring a unique race displaying geographical variations determined by climate, then further variations arising from the encounter between different populations.

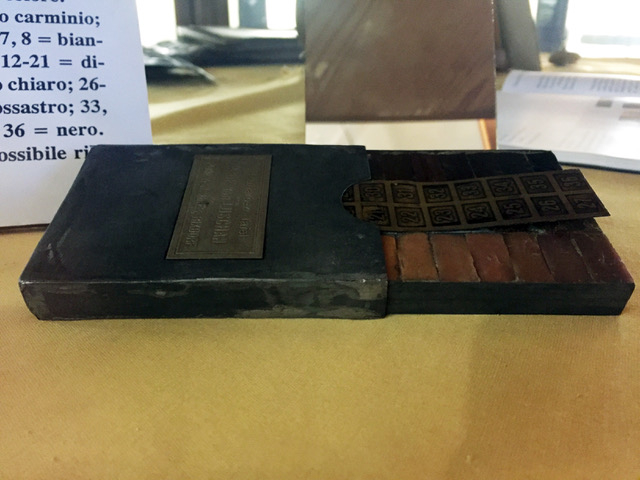

Felix von Luschan's color look up table held by the Bologne Museum of anthropology

However, this supposed authenticity of color needs to be counterbalanced by several observations. Many studies have shown the incoherence of any claims to objectivity given the inherently subjective incursions in all visual observation36. Finsch thus assessed skin color using a scale drawn up by Broca37. He nevertheless complained that this color chart “leaves much to be desired, and rarely renders skin colors exactly, with the precise hue generally lying between two figures”38. The authentic coloring of Finsch’s casts is even more debatable for they were produced on white plaster casts by Louis Castan (1828-1908), at the Berlin Panoptikum. This was a popular exhibition venue run by the Castan brothers where waxworks were displayed alongside a variety of items including ethnographic objects, elephant tusks, and mummies, and where exhibitions of human phenomena were held in which individuals were turned into circus freaks39.

Casts made from living individuals by Otto Finsch, held by the Florence museum of anthropology and ethnology

These two casts by Finsch from the Florentine collection [figures 4 and 5] are high-reliefs on a rectangular block. On the bottom right is the model’s first name, gender, and place of provenance. The number engraved above the neck is the reference in Finsch’s catalogue. The cast of Ibobon from Gilbert Island, number 48, thus bears the inscription: “between eighteen and twenty years old; pretty young woman; height 1m50; chest size 86 cm, head 182 mm; black hair, uniform color; typical, but very light in color”40. Ibobon’s face is quite detailed: the eyelashes and eyebrows are painted carefully, and there is a red necklace in relief. The cast of Tamaituk (Tomaituk in the catalogue), from the northern tip of New Ireland (Papua New Guinea), is striking for its uniform color, turning the face into an unrealistic and expressionless mask. It corresponds to number 108 in the catalogue, with the laconic description, “from Nusa Island; strong man about 25 years old; height 188 cm”41.

Yet the improbably scientific nature of these artefacts did nothing to dampen anthropologists’ enthusiasm. Their eagerness needs placing in context, for at this time colonial and universal exhibitions, in which non-Western populations were placed on display,42 were highly popular with scientists and the general public alike. The tale of th43e two Aka pygmies studied by Mantegazza is only one tragic example among many of placing humanity on display and of scientific racism. During Giovanni Miani’s final expedition, concluding in his death in 1872, a king apparently gave him two pygmies. On Miani’s death, the two Akas, whom he had named Cher Allà (Divine Fortune) and Thiebaut, were transported to Italy. This ancient population mentioned by Homer was viewed by the scientific community as the missing link between humans and apes in evolutionary theories. Their arrival made the headlines and sparked public curiosity, and also drew the attention of several European anthropologists including Mantegazza. It was soon discovered that the reason Chair Alla and Thiebaut were especially small was because they were still children. In 1883, Thiebaut died of tuberculosis during this enforced trip to Italy. It is not known what became of Chair Alla.

But this type of spectacle was not unanimously appreciated in anthropological circles44. Claude Blanckaert points out that “the creation of ever more ‘anthropo-zoological’ spectacles raised ethical questions which were immediately perceived by contemporaries”45. The success of casts could be one explanation for this reticence, for they were a morally preferable compromise to human fairs. Otto Finsch’s collection of facial molds acquired by Mantegazza in 1885 was mainly exhibited to a public composed solely of scientists and students. During the years 1909-1910, the room of physical anthropology – supplemented by a donation by the ethnologist and anthropologist Elio Modigliani (1860-1932)46 – was placed after the ethnographic collections, in a layout corresponding to the evolution of races. An article published in 1909 in the Archivio per l’antropologia e la etnologia throws light on what was on display:

The museum still owns a collection of 163 colored plaster masks [displayed] in a separate room. They are mainly of individuals from New Guinea, New Brittany, and Micronesia, and come from the Finsch collection. Forty-three other masks were produced by Doctor Modigliani during his journeys among the Toba, on the Mentawai Islands and Engano. There is also an Aka cast produced in Florence, and five other busts of negroes of various provenance, two Americans, two from the New Hebrides, and one Tasmanian47.

This description is supplemented by the words used by Aldobrandino Mochi (1875-1931), appointed director of the museum after Mantegazza’s death in 1910, in commemoration of him. He stated that the layout reflected the thought of the museum’s founder and his wish to place Italian anthropology midway between the French anthology of Paul Broca, deemed overly focused on anatomical study, and the British school, felt to be too ethnographic:

With its presentation, first, of skulls, skeletons, masks and various plaster models, photographs, and hair samples for somatological research, and with its collection, second, of the most characteristic craftwork of various people for ethnographic study, the museum corresponds to the concept that physical anthropology should be mutually combined and integrated with the history of culture. Mantegazza produced this concept from observation of the relative internal homogeneity of the somatological characteristics of human groups with primitive though clearly differentiated cultures, and from a certain parallel between the degree of cultural evolution and the hierarchy of certain morphological characteristics48

These accounts enable us to place the Florentine collection of casts within the history of European anthropology. Its initial composition reflected the interest in south-east Asia, a geographical frontier raising scientific issues, for the British anthropologist Alfred Russel Wallace and Charles Darwin had both arrived at their theories of evolution on the basis of research conducted in this region. But the newly formed Italian state soon turned a covetous eye to the African continent, causing a shift in the center of interest of Italian anthropological studies. During the two decades following unification, the country took part in the scramble for Africa. After taking Assab (1882) and conquering Massawa (1885), initial forays by the Italian state led to the establishment of the colony of Eritrea (1890) and the conquering of Somalia (1908).

Making race visible under fascism: plaster casts as proof

After Mantegazza’s death in 1910, the museum, directed by Aldobrandino Mochi, moved to the Palazzo Nonfinito, where it is still housed today. The collections were only definitively transferred there in 1923. The refurbishment of the museum took so long that Mochi, who died in 1931, was unable to attend its official opening in the presence of King Vittorio Emanuele III, on April 30, 1932. The museum opened to the public shortly after, on June 16, 1932. In the initial plans for refurbishment overseen by Mochi, the anthropological rooms were to occupy the ground floor and the main reception floor [piano nobile], though in fact the ethnographic collections were eventually displayed there. The anthropological casts, osteology collection, and the skull collection were not included in the exhibition circuit, but placed in the attics. They were next to the laboratories, library, and classrooms, and used mainly for teaching purposes49.

The years during which the museum moved to Palazzo Nonfinito were ones of profound political upheaval in Italy, during which colonial policy was intensified and fascism came to power. In 1911, the Giovanni Giolitti government decided to invade Tripolitania and Cyrenaica (present-day Libya). This campaign with markedly nationalist overtones was an opportunity to celebrate fifty years of unification. After the First World War, Italy’s hopes to strengthen its hold in Africa during negotiations of the Treaty of Versailles, in recompense for the heavy tribute it had paid for supporting the Triple Entente, were dashed when it only obtained Jubaland – a territory in south-west Somalia. This disappointment was one of the arguments put forward by the fascist regime to support its claims in Africa. After Benito Mussolini took power in 1922, the fascist regime stepped up its colonial actions. This led to the Second Italo-Ethiopian war, resulting in the proclamation of the Empire in 1936 and the founding of the colony of Italian East Africa, comprising Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Somalia. The “frenetic expansion”50 characterizing fascism was directed by Mussolini, who justified Italian expansion across the Mare nostrum as a way of guaranteeing the survival and prosperity of the Italian people. The imperialist rhetoric of fascism was accompanied by increasingly radical racial discourse. It should be remembered that the first race law was promulgated in April 1937, in a prelude to the 1938 Manifesto of Race. It outlawed relations of a conjugal nature between Italian citizens and African women, making it an offence punishable by up to five years in prison.

Italian colonialism was long judged to be less violent than that of its European neighbors – a view stemming from the myth of Italy as a regionalist and rural country peopled by good, stay-at-home folk little inclined to warfare. But major works published over the past twenty years have broken the long historiographic silence51, and called this prejudice into question52. Nevertheless, the history of the key role played by aesthetic and analogical representations in the process of othering is still to be explored by scholarship.

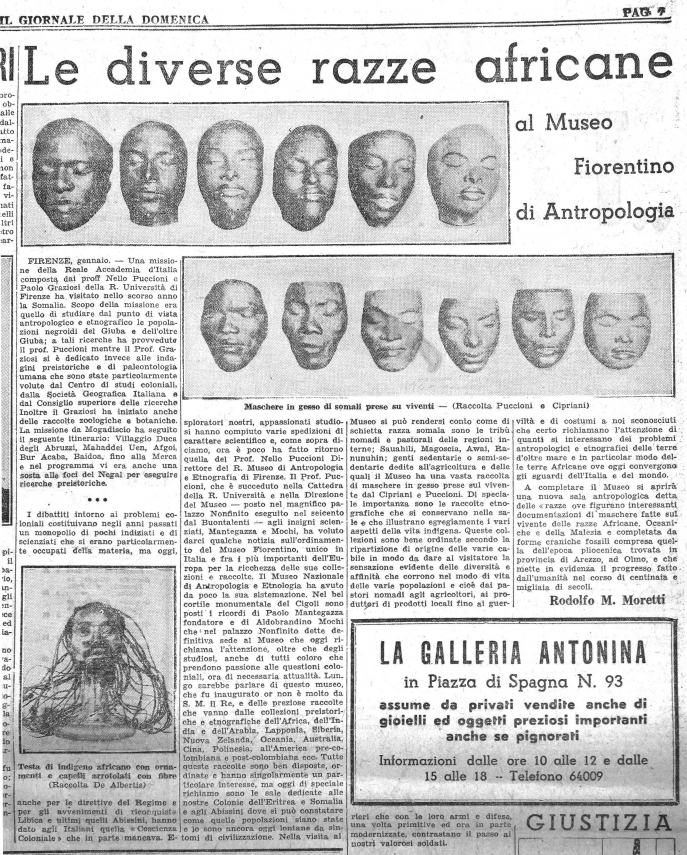

This territorial expansion policy and attendant racial theories of fascism influenced the museographic project of the museum of anthropology in Florence. Africa progressively became the preferred field of Italian anthropologists53. Research missions led by successive directors of the museum – Nello Puccioni (1881-1937) and Lidio Cipriani (1892-1962) – to Italian colonies during the years 1920-1940 were part of a broad consensus about the Mussolini regime’s colonial policy54. Puccioni thus took part in three expeditions – two in Somalia (1924, 1935), one in Cyrenaica (current Libya)55 – , while Cipriani went to Africa at least seven times, particularly Ethiopia and Eritrea. The practice of taking molds from nature was extensively employed by these two anthropologists. Puccioni brought forty molds back from Somalia, but the greatest contribution to the Florentine collection was by Cipriani, who produced over 350.

Cipriani’s intellectual baggage included the evolutionary theories of Darwin and of the criminologist Cesare Lombroso56. His method of fieldwork consisted in taking somatometric measurements, photographing subjects,57 then making molds. At the same time, he wrote intensively, seeking to demonstrate the biological inferiority of African populations58. His theories merely reiterate the most commonplace and dangerous cliches of racism, stating that interbreeding resulted in idleness, decadence of populations, and prevented any possibility of progress. This violence may be clearly seen in Un assurdo etnico: l’impero etiopico (1936), in which Cipriani describes Ethiopians as a “decadent residue”59, in a forerunner to the Manifesto of Race (1938) of which he was a signatory60.

Like his predecessors, Cipriani attached particular importance to facial casts which he viewed as “scientific documents of the first order, preferable to any metric or photographic data”61. To his mind, “morphological detail” was of greater value than any skull measurements: “everybody knows that one can recognize the ethnic provenance of an individual at a glance; when that is not immediately possible, measurements are generally of no help for understanding what group an individual belongs to”62. In addition to these strictly anthropological reasons, I believe we should add the fact that these casts could be displayed to the scientific community and to a broader public. Their strong visual impact and the fascination they exerted by their compelling realism made them a powerful propaganda tool. Unlike the casts made by Otto Finsch, Cipriani did not indicate his models’ first names, only identifying them by one (sometimes two) numbers engraved on the skull, corresponding to the inventory of the museum’s anthropological collection and the catalogue of its collection of plaster casts63.

Casts made on living individuals by Lidio Cipriani, held by the museum of anthropology and ethnology in Florence (1/2)

Casts made on living individuals by Lidio Cipriani, held by the museum of anthropology and ethnology in Florence (2/2)

Cipriani made over 350 casts, and during the 1930s most Italian university anthropology museums bought reproductions to support his theories. He also used these casts to back up his arguments during conferences in London, Paris, and New York64. In 1934, he presented twenty-four examples in the anthropological room in the Italian section of the Sahara exhibition held at the Trocadéro in Paris65. They were also displayed in the pavilion illustrating the racial policy deployed in Libya and in East African territories during the Triennale delle terre d’Oltremare exhibition in Naples (1940).

Publicity campaign for the selling of facial casts made by Nello Puccioni et Lidio Cipriani.

I thank Jacopo Moggi Cecchi for having informed me of this document

It is highly likely that Cipriani played a leading role in reintegrating plaster cast collections into the exhibition circuit at the Florence museum of anthropology. Puccioni, the director of the museum from 1931 until his death in 1937, seconded by Cipriani, moved the anthropological collections of skulls and plaster casts down to the ground floor from the attics where they had previously been confined:

Puccioni was able to place several series which had not yet been put away after Mochi had moved the museum from its premises on Via Gino Capponi to the Palazzo Nonfinito: three rooms of collections gathered by Modigliani in Malaysia, two from Oceania, three from Africa, in addition to the skull collection and masks from the ground-floor room. Very important items produced by Cipriani in various zones of Africa […] were added to these collections under Puccioni’s supervision66.

These years coincided with the war in Ethiopia and the hardening of the fascist regime’s racial policy. In 1936, several newspaper articles mentioned the opening of “a new anthropology room, known as the race room”67 in the museum of anthropology in Florence. It included “a large display case in which an improbable number of colored plaster casts are exhibited. They are ‘masks’ taken from living people in Malaysia by Modigliani, in Somalia by Puccioni, and in other zones of Africa and India by Cipriani”68. One journalist described the room in the following terms: “these are the faces and expressions of “our” so distant “relatives” – faces and expressions which, as I felt on several occasions, stir something like a vague memory of people once known. Might our subconscious be returning to the origins? Maybe”69. This observation illustrates how plaster casts were received visually. They were perceived less as representing infinite human diversity than as demonstrating a racist concept of humanity, in which African populations were relegated to the status of prehistoric man.

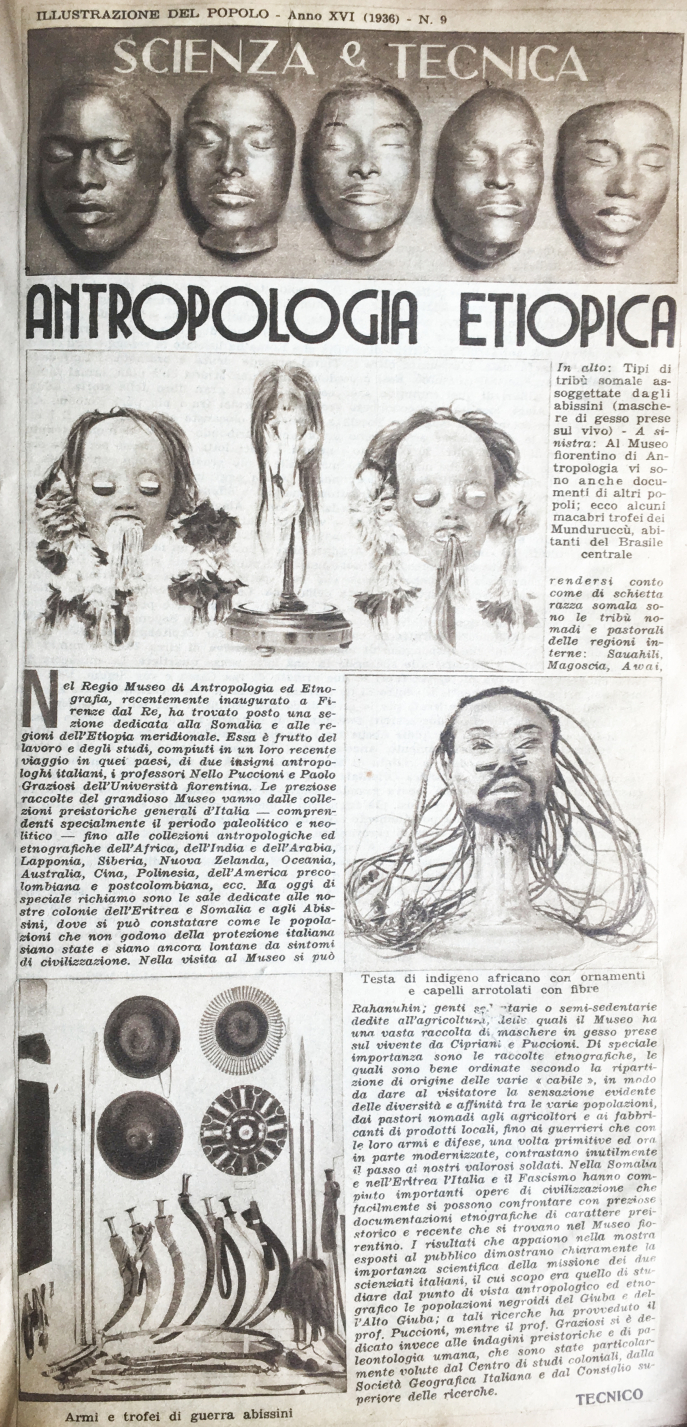

On the left: article by Rodolfo Moretti, “Le diverse razze africane”, Il Giornale della Domenica, January 12-13, 1936, p. 7

On the right: anonymous article, “Antropologia etiopica”, Illustrazione del popolo, 1936

These objects, which are inherently non-scientific due to the systematic intrusion of subjectivity in their manufacture, were nevertheless used by anthropologists as of the late nineteenth century to observe the bodies of distant populations. They changed status on being placed in a museum space open to the public, for their hierarchical layout in the museum rooms was used to support theories on the classification of humanity. They thereby acquired the status of tangible scientific proof of the existence of races.

These casts raise many ethical and museographic questions. Cipriani’s collection is the most problematic. After the Second World War, the casts were hung provisionally in a space not accessible to the public. They are currently stored in stairwells at the museum. The molds are also inaccessible, being piled up behind cupboards. Nowadays the museum only has twenty or so examples on display. Five of these, produced by Nello Puccioni, are exhibited in two display cases about Somalia, among such varied objects as masks, jewelry, utensils, and so on, without any attempt to place them in context or perspective. Fourteen casts produced by Cipriani are part of an educational panel called “Diversity is a value” alongside two other panels, one going over the history of the Cipriani collection and the other asking the supposedly rhetorical question: “Is it appropriate to classify mankind based on [skin color]?”.

Accrochage provisoire des moulages, photothèque du musée d’anthropologie, SMA, Università degli Studi di Firenze

Educational wall : « Diversity is a value…different like you! », Florence Museum of anthropoloy

Thus since the fall of fascism through to the present day, the Florentine museum’s collection of plaster casts has been progressively relegated to the confines of history. The materiality of these artefacts which are stacked in boxes and kept out of sight, together with their conservation and their status, alert us to the need to historicize these objects, and to reintroduce them into an exhibition circuit capable of driving a much-needed deconstruction of racial categories.

Notes

1

Jacopo Moggi Cecchi, Roscoe Stanyon (eds.), Il Museo di Storia Naturale dell’Università degli Studi di Firenze. Le collezioni antropologiche e etnologiche, Florence, Florence University Press, 2014; Nicola Labanca, ““Un nero non può essere bianco’. Il Museo Nazionale di Antropologia di Paolo Mantegazza e la Colonia Eritrea”, in N. Labanca (ed.), L’Africa in vetrina, Trevise, Pagus, 1992, p. 69-106.

2

On Paolo Mantegazza, see Giovanni Landucci (ed.), Paolo Mantegazza e il suo tempo: l’origine e lo sviluppo delle Scienze antropologiche in Italia [convegno di studio, Firenze, 30-31 maggio 1985], Milan, Ars medica antiqua editrice, 1986; Cosimo Chiarelli, Walter Pasini (eds.), Paolo Mantegazza: medico, antropologo, viaggiatore [selezione di contributi dai convegni di Monza, Firenze, Lerici, Firenze], Florence, Florence University Press, 2002; Giulio Barsanti, Mariangela Landi, “Fra antropologia, etnologia e psicologia comparata: il museo della ‘storia naturale dell’uomo’. Paolo Mantegazza e Aldobrandino Mochi”, in J. Moggi Cecchi, R. Stanyon (eds.), Il Museo di Storia Naturale dell’Università degli Studi di Firenze. Le collezioni antropologiche e etnologiche, Florence, Florence University Press, 2014, p. 3-22.

3

Giovanni Landucci, Darwinismo a Firenze tra scienza e ideologia: 1860-1900, Florence, L.S. Olschki, 1977; Barbara Continenza, “Il dibattito sul darwinismo in Italia nell’Ottocento”, in Storia sociale e culturale d’Italia. V. La cultura filosofica e scientifica, II. La storia delle scienze, Busto Arsizio, Bramante ed., 1988.

4

Paolo Mantegazza, “Del metodo dei nostri studi antropologici” (1871), in P. Mantegazza, L’Uomo e gli uomini. Antologia di scritti antropologici (eds. G. Barsanti, F. Barbagli), Florence, Edizioni Polistampa, 2010, p. 55.

5

Paolo Mantegazza, “Del metodo dei nostri studi antropologici” (1871), in P. Mantegazza, L’Uomo e gli uomini. Antologia di scritti antropologici (eds. G. Barsanti, F. Barbagli), Florence, Edizioni Polistampa, 2010, p. 56.

6

Paolo Mantegazza, “Trent’anni di storia della Società Italiana d’Antropologia e etnologia e Psicologia comparata” (1901), in P. Mantegazza, L’Uomo e gli uomini. Antologia di scritti antropologici (eds. G. Barsanti, F. Barbagli), Florence, Edizioni Polistampa, 2010, p. 236.

7

Monica Zavattaro, “Le collezioni etnografiche del Museo di Storia Naturale di Firenze: storia e prospettive museologiche e museografiche”, Museologia scientifica, no 8, 2014, p. 57.

8

La direzione, “Avviso”, Archivio per l’Antropologia e la etnologia, vol. IV, 1874, p. 407.

9

Jacopo Moggi Cecchi, “Le collezioni antropologiche”, in J. Moggi Cecchi, R. Stanyon (eds.), Il Museo di Storia Naturale dell’Università degli Studi di Firenze. Le collezioni antropologiche e etnologiche, Florence, Florence University Press, 2014, p. 183-196.

10

Jacopo Moggi Cecchi, “Le collezioni antropologiche”, in J. Moggi Cecchi, R. Stanyon (eds.), Il Museo di Storia Naturale dell’Università degli Studi di Firenze. Le collezioni antropologiche e etnologiche, Florence, Florence University Press, 2014, p. 184.

11

Paolo Mantegazza, “Dei caratteri gerarchici del crnaio umano. Studi di critica craniologica” (1875), in P. Mantegazza, L’Uomo e gli uomini. Antologia di scritti antropologici (eds. G. Barsanti, F. Barbagli), Florence, Edizioni Polistampa, 2010, p. 119-131.

12

Paolo Mantegazza, “Dei catteri gerarchici del cranio umano. Studi di critica craniologica” (1875), in P. Mantegazza, L’Uomo e gli uomini. Antologia di scritti antropologici (eds. G. Barsanti, F. Barbagli), Florence, Edizioni Polistampa, 2010, p. 127.

13

Paolo Mantegazza, “Dei catteri gerarchici del cranio umano. Studi di critica craniologica” (1875), in P. Mantegazza, L’Uomo e gli uomini. Antologia di scritti antropologici (eds. G. Barsanti, F. Barbagli), Florence, Edizioni Polistampa, 2010, p. 122.

14

Cf. in this issue, the articles by Maddalena Carli, “Patrimonialiser la déviance” and Silvano Montaldo, “To Be Done with Cesare Lombroso”.

15

Claude Blanckaert, “La crise de l’anthropométrie. Des arts anthropotechniques aux dérives militantes”, in Cl. Blanckaert (ed.), Les politiques de l’anthropologie. Discours et pratiques en France (1860-1940), Paris, L’Harmattan, 2001, p. 95-172; Hartmann Heinrich, “Une affaire de marges. L’anthropométrie au conseil de révision, France-Allemagne, 1880-1900”, Le Mouvement Social, no 256, 2016, p. 81-99 [on line].

16

Claude Blanckaert, “La mesure de l’intelligence. Jeux des force vitales et réductionnisme cérébral selon les anthropologues français (1860-1880)”, Ludus vitalis, 1994, II/3, p. 53 and 60.

17

To reduce the number of characters and for ease of reading, I do not systematically place the terms race, racial, and racialist in scare quotes.

18

Nicoletta Pireddu, “Paolo Mantegazza: ritratto dell’antropologo come esteta”, in C. Chiarelli, W. Pasini (eds.), Paolo Mantegazza: medico, antropologo, viaggiatore [selezione di contributi dai convegni di Monza, Firenze, Lerici, Firenze], Florence, Florence University Press, 2002, p. 183-196.

19

Paolo Mantegazza, Epicuro. Saggio di una filosofia del bello, Milan, Fratelli Treves editori, 1891, p. 47.

20

Paolo Mantegazza, “L’uomo e gli uomini. Lettera etnologica del Prof. Paolo Mantegazza al Prof. Enrico Giglioli, estratta dal Viaggio intorno al Globo della R. Pirocorvetta Italiana Magenta” (1876), in P. Mantegazza, L’Uomo e gli uomini. Antologia di scritti antropologici (eds. G. Barsanti, F. Barbagli), Florence, Edizioni Polistampa, 2010, p. 101, 107, 115.

21

Paolo Mantegazza, La Physionomie et l’expression des sentiments, Paris, Alcan, 1885, p. 65.

22

Paolo Mantegazza, La Physionomie et l’expression des sentiments, Paris, Alcan, 1885, p. 62.

23

Paolo Chiozzi, “Fotografia e antropologia nell’opera di Paolo Mantegazza”, Archivio Fotografico Toscano, 1987, no. 6, p. 51-61; Alberto Baldi, “Paolo Mantegazza: alle origini dell’Antropologia visiva italiana”, in Paolo Mantegazza e il suo tempo: l’origine e lo sviluppo delle scienze antropologiche in Italia, Milan, Ars medica antiqua editrice, 1986, p. 69-76.

24

Arturo Issel (ed.), Istruzioni scientifiche per i viaggiatori [1874-1881], Rome, Eredi Botta, 1881.

25

Arturo Issel (ed.), Istruzioni scientifiche per i viaggiatori [1874-1881] Rome, Eredi Botta, 1881, p. 358.

26

Enzo Alliegro, Antropologia italiana: storia e storiografia, 1869-1975, Florence, SEID, 2011, p. 87; Alberto Baldi, “Ipse vidit. Fotografia antropologica ottocentesca e possesso del mondo”, EtnoAntropologia, vol. 4, no 1, 2016, p. 3-25.

27

Paul Broca, Instructions générales pour les recherches et observations anthropologiques (anatomie et physiologie), Paris, Victor Masson et fils, 1865.

28

Marc Renneville, “Un terrain phrénologique dans le Grand Océan (autour du voyage de Dumoutier à bord de l’Astrolabe en 1837-1840)”, in Cl. Blanckaert, Le Terrain des sciences humaines (Instructions et enquêtes. XVIIe-XXe siècles), Paris, L’Harmattan, 1996, p. 89-138; Romain Duda, “Dumoutier et la collecte de moulages anthropologiques. Une empreinte de l’alterité au dix-neuvième siècle”, Id. Juhé-Beaulaton, V. Leblan (eds.), Le Spécimen et le Collecteur. Savoirs naturalistes, pouvoirs et altérités (XVIIIe-XXe siècles), Paris, Publications du Muséum national d’histoire naturelle, 2018, p. 315-347.

29

Paolo Mantegazza, Epicuro. Saggio di una filosofia del bello, Milan, Fratelli Treves editori, 1891, p. 223.

30

Sandra Puccini, “Gli Akka del Miani (1872-1883)”, in S. Puccini, Andare lontano. Viaggi ed etnografia nel secondo Ottocento, Rome, Carrocci, 1999, p. 75-112.

31

Paolo Mantegazza, Arturo Zannetti, “I due Akka del Miani”, Bollettino della Società Geografica Italiana, t. XI, 1874, p. 492.

32

On Otto Finsch, see Andrew Zimmerman, Anthropology and Antihumanism in Imperial Germany, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2001, p. 165-166; Hilary Susan Howes, The Race Question in Oceania. A. B. Meyer and Otto Finsch between metropolitan theory and field experience, 1865-1914, New York, Peter Lang, 2013, p. 147-169.

33

Otto Finsch, Gesichtsmasken von Völkertypen der Südsee und dem malayischen Archipel, nach Lebenden abgegossenin den Jahren 1879-1882, Brême, Druck von Homeyer & Meyer, 1887.

34

Pierre Labrousse, “Les races de l’Archipel ou le scientisme in partibus (France, XIXe siècle)”, Archipel, no. 60, 2000, p. 235 [on line].

35

Pierre Labrousse, “Les races de l’Archipel ou le scientisme in partibus (France, XIXe siècle)”, Archipel, no 60, 2000, p. 237 [on line].

36

Jonathan Crary, Techniques of the Observer. On Vision and Modernity in the Nineteenth Century, Cambridge, Mass., The MIT Press, 1990; Lorraine Daston, Peter Galison, “The image of objectivity”, Representations, no 40, 1992, p. 81-128; Lorraine Daston, Peter Galison, Objectivity, New York, Zone Books, 2007; Nélia Dias, “La fiabilité de l’œil”, Terrain, no 33, 1999 [on line].

37

Paul Broca, Instructions générales pour les recherches et observations anthropologiques (anatomie et physiologie), Paris, Victor Masson et fils, 1865, planche V.

38

Otto Finsch, Anthropologische Ergebnisse einer Reise in der Südsee und dem malayischen Archipel in den Janren 1879-1882, Berlin, A. Asher, 1884, p. 1; republished in H. Susan Howes, The Race Question in Oceania. A. B. Meyer and Otto Finsch between metropolitan theory and field experience, 1865-1914, New York, Peter Lang, 2013, p. 149.

39

On the Panoptikum, see Peter Letkemann, “Das Berliner Panoptikum: Namen, Häuser une Schicksale”, Mitteilungen des Vereins für die Geschichte Berlins, no 69, 1973, p. 319-326; Stephan Oettermann, “Alles-Schau: Wachsfigurenkabinette und Panoptiken”, in L. Kosok, M. Jamin (eds.), Viel Vergnügen. Öffentliche Lustbarkeiten im Ruhrgebiet der Jahrhundertwende, Essen, Ruhrlandmuseum-P. Pomp, 1992. On the links between the Panoptikum and contemporary anthropology, see in particular Sierra Ann Bruckner, The Tingle-tangle of modernity. Popular anthropology and the cultural politics of identity in Imperial Germany, Ann Arbor, UMI, 1999, p. 250-251; Stefan Goldmann, ”Wilde in Europa. Aspekte und Orte ihrer Zurschaustellung”, in T. Theye (ed.), Wir und die Wilden. Einblicke in eine kannibalische Beziehung, Reinbek bei Hamburg, Rowohlt, 1985, p. 259-261; Andrew Zimmerman, Anthropology and Antihumanism in Imperial Germany, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2001, p. 16-20.

40

Otto Finsch, Gesichtsmasken von Völkertypen der Südsee und dem malayischen Archipel, nach Lebendenabgegossenin den Jahren 1879-1882, Brême, Druck von Homeyer & Meyer, 1887, p. 8.

41

Otto Finsch, Gesichtsmasken von Völkertypen der Südsee und dem malayischen Archipel, nach Lebenden abgegossenin den Jahren 1879-1882, Brême, Druck von Homeyer & Meyer, 1887, p. 14.

42

Nicolas Bancel, Pascal Blanchard, Gilles Boetsch, Éric Deroo, Sandrine Lemaire (eds.), Zoos humains. De la Vénus hottentote aux reality shows, Paris, La Découverte, 2002. Read too the critique of this exhibition by Claude Blanckaert: “Spectacles ethniques et culture de masse au temps des colonies”, Revue d’histoire des sciences humaines, no 7, 2002, p. 223-232; Guido Abbbattista, Umanità in mostra. Esposizioni etniche e invenzioni esotiche in Italia (1880-1940), Triste, Edizioni Università di Trieste, 2013.

43

Sandra Puccini, “Gli Akka del Miani (1872-1883)”, in S. Puccini, Andare lontano. Viaggi ed etnografia nel secondo Ottocento, Rome, Carrocci, 1999, p. 75-112.

44

Armand de Quatrefages supported a project to exhibit living specimens during the world fair, which was rejected by the empress. See Isabelle Gaurin, “Du rapt légitimé de “sujet d’étude vivants”. Une démarche de Quatrefages auprès du ministère de l’Instruction publique (1891)”, in J. Guillerme (ed.), Les Collections. Fables et programmes, Seyssel, Champ Vallon, 1993; Claude Blanckaert, “Pour une théorie évolutive humaine. Armand de Quatrefages, la formation des races et le darwinisme au Muséum national d’histoire naturelle”, Revue d’histoire des sciences humaines, no 27, 2015, p. 189-230.

45

Claude Blanckaert, “Spectacles ethniques et culture de masse au temps des colonies”, Revue d’histoire des sciences humaines, no 7, 2002, p. 230.

46

A friend of Mantegazza and member of the Società italiana per l’antropologia e la etnologia, Modigliani went on three expeditions to the Indonesian archipelago. During a voyage to the island of Nias, he produced molds on the populations of Nias, Toba, and Engano. See Elio Modigliani, L’Isola delle donne, viaggio ad Engano, Milan, U. Hoepli, 1894, p. 79-80.

47

Nello Puccioni, “Museo nazionale di Antropologia e Etnologia di Firenze. – Le collezioni antropologiche”, Archivio per l’antropologia e la etnologia, vol. XXXIX, 1909, p. 272. The reference in this text is probably to five facial casts of Tasmanian populations obtained by exchange by the zoologist and anthropologist Enrico Hillyer Giglioli (1845-1909).

48

Aldobrandino Mochi, “Rendiconti della Società Italiana d’Antropologia, Etnologia e Psicologia comparata. Adunanza straordinaria tenuta il 6 novembre 1910 per commemorare Paolo Mantegazza” (1910), in P. Mantegazza, L’Uomo e gli uomini. Antologia di scritti antropologici (eds. G. Barsanti, F. Barbagli), Florence, Edizioni Polistampa, 2010, p. 276.

49

Giulio Barsanti, Mariangela Landi, “Fra antropologia, etnologia e psicologia comparata: il museo della “storia naturale dell’uomo”. Paolo Mantegazza e Aldobrandino Mochi”, in J. Moggi Cecchi, R. Stanyon (eds.), Il Museo di Storia Naturale dell’Università degli Studi di Firenze. Le collezioni antropologiche e etnologiche, Florence, Florence University Press, 2014, p. 20-21.

50

Nicola Labanca, Outre-mer. Histoire de l’expansion coloniale italienne, Grenoble, Ellug, 2014, p. 148.

51

Valeria Deplano, Alessandro Pes (eds.), Quel che resta dell’impero. La cultura coloniale degli italiani, Milan- Udine, Mimesis, 2014; Riccardo Bottoni (ed.), L’impero fascista. Italia ed Etiopia, 1935-1941, Bologne, Il Mulino, 2008; Patrizia Palumbo (ed.), A Place in the Sun. Africa in Italian Colonial Culture from Post-Unification, Berkeley-London, University of California Press, 2003.

On the fascist government’s colonial policy, see Nicola Labanca, Oltremare. Storia dell’espansione coloniale italiana, Bologne, Il Mulino, 2000; Enzo Collotti (ed.), Fascismo e politica di potenza. La politica estera 1922-1939, Florence, La Nuova Italia, 2000; Nicola Labanca, “Politica e amministrazione coloniale dal 1922 al 1934”, in E. Collotti (ed.), Fascismo e politica di potenza. Politica estera, 1922-1939, Milan, La Nuova Italia, 2000, p. 81-136; Nicola Labanca, “Il razzismo coloniale italiano”, in A. Burgio (ed.), Nel nome della razza. Il razzismo nella storia d’Italia: 1870-1945, Bologna, Il Mulino, 2000; Angelo Del Boca, Gli Italiani in Africa orientale. 2. La conquista dell’impero, Rome/Bari, Laterza, 1979; Angelo Del Boca, Gli Italiani in Africa orientale. 3. La caduta dell’impero, Rome-Bari, Laterza, 1982; Angelo Del Boca, L’Africa nella coscienza degli Italiani. Miti, memorie, errori, sconfitte, Rome-Bari, Laterza, 1992; Angelo Del Boca (ed.), Le guerre coloniali del fascismo, Rome-Bari, Laterza, 1991.

52

See Angelo Del Boca, Italiani brava gente? Un mito duro a morire, Vicenza, Neri Pozza, 2005; David Bidussa, Il mito del bravo italiano, Milan, Il saggiatore, 1994; Angelo del Boca, “Il mancato dibattito sul colonialismo. L’Africa nella coscienza degli Italiani”, in A. del Boca, Miti, memorie, errori, sconfitte, Rome-Bari, Laterza, 1992, p. 111-127.

53

Sandra Puccini, Massimo Squillacciotti, “Per una prima ricostruzione critico bibliografica degli studi demo-etno-antropologici italiani nel periodo tra le due guerre”, in Studi antropologici italiani e rapporti di classe, Milan, F. Angeli, 1980, p. 67-93; P. M. Taylor, “Anthropology and the “Racial Doctrine” in Italy before 1940”, Antropologia contemporanea, no 1-2, 1988, p. 45-58.

54

Maria Pia Di Bella, “Ethnologie et fascisme: quelques exemples”, Ethnologie française, vol. XVIII, no 2, 1988, p. 131-136.

55

On Puccioni, see Mariangela Landi, Jacopo Moggi Cecchi, “L’antropologia coloniale: “dai popoli del mondo all’uomo del fascismo”. Nello Puccioni e Lidio Cipriani”, in J. Moggi Cecchi, R. Stanyon (eds.), Il Museo di Storia Naturale dell’Università degli Studi di Firenze. Le collezioni antropologiche e etnologiche, Florence, Florence University Press, 2014, p. 23-32; Beatrice Falcucci, Fausto Barbagli, “La missione in Cirenaica del 1928 nei diari inediti di Nello Puccioni”, Archivio per l’antropologia e la etnologia, vol. CXLVII, 2017, p. 71-84.

56

Jacopo Moggi-Cecchi, “La vita e l’opera scientifica di Lidio Cipriani”, AFT. Rivista di storia e fotografia, no 11, 1990, p. 11-18.

57

On Lidio Cipriani’s photography, see Paolo Chiozzi, “Autoritratto del razzismo: le fotografie antropologiche di Lidio Cipriani”, in La Menzogna della razza. Documenti e immagini del razzismo e dell’antisemitismo fascista, Bologne, Grafis, 1994, p. 91-94.

58

Lidio Cipriani, Titoli e pubblicazioni, Florence, Stamperia Fratelli Parenti di G., 1940.

59

Lidio Cipriani, Un assurdo etnico. L’impero etiopico, Florence, Bemporad, 1935, p. 224.

60

Francesca Cavarocchi, “La propaganda razzista e antisemtia di uno ‘scienziato’ fascista. Il caso di Lidio Cipriani”, Italia contemporanea, no 219, 2000, p. 193-225.

61

Lidio Cipriani, “Ricerche antropologiche sulle popolazioni della ragione del Lago Tana”, Accademia d’Italia, vol. XVI, 1938, p. 8.

62

Lidio Cipriani, “Viaggio antropologico nell’Europa Centrale”, Rivista di biologia, vol. XVI, fasc. II, 1934, p. 9.

63

Number 221 and number 6217: “plaster facial cast of one Betguik Senimagallé, ♂, 24-years-old, modeled on the living subject in Uasintet” [mask molded by Cipriani during the mission by the Center for colonial studies in Florence to northern Eritrea in 1937-1938]; no. 328 in Cipriani’s collection corresponds to number 6323 in the inventory of the anthropological collection, which indicates: “plaster facial cast of one Sidamo, ♂, 29-years-old, modeled in Dalle” [molded from a living subject by Cipriani during the “Mostra Triennale d’Oltremare e Reale Accademia d’Italia in Etiopia occidentale” mission].

64

On the occasion of the centenary of the British Association for the Advancement of Science. In 1932, during the Third International Eugenics Congress held in New York, he presented a paper on the mental capacities of African populations, and displayed some of his collection of facial casts.

65

Lidio Cipriani, “Anthropologie”, in Exposition du Sahara. Paris. Musée d’ethnographie. Le Sahara Italien. Guide officiel de la section italienne, Rome, Ministère des colonies, 1934, p. 67-72.

66

“Commemorazione di Nello Puccioni”, Archivio per l’antropologia e la etnologia, vol. LXVII, 1937, p. 22.

67

R. M. Moretti, “Le razze africane nel museo fiorentino”, Il Mattino, April 30, 1936.

68

Nando Visoli, “Una visita alle due nuove sale del Museo di Antropologia e di Etnografia”, La Nazione, November 28, 1936, p. 3.

69

Nando Visoli, “Una visita alle due nuove sale del Museo di Antropologia e di Etnografia”, La Nazione, November 28, 1936, p. 3.