(Kyoto University - Institute for Research in Humanities)

Nomenclature shapes our perceptions and modes of thought. The ways the Japanese perceived others changed drastically with the introduction of racial terminology and hierarchies from Western countries during the late Edo period (1603-1868) and early Meiji period (1868-1912). Terminology such as “Caucasoid”, “Mongoloid”, and “Negroid”, or “White Race”, “Yellow Race”, and “Black Race”, which continue to be used in school textbooks and encyclopedia down to the present day, arrived in Japan during these periods as purportedly “scientific knowledge”. The former nomenclatures can be traced back to Johan F. Blumenbach, a German anthropologist, whilst the latter classifications were devised by Georges Cuvier, a French naturalist. Although this terminology was carried over from the original books from the West, the meanings attached to these terms shifted under the effects of modern Japan’s nation-building and the expansion of its empire. Race is a contested and constantly evolving term, so it stands to reason that its associated nomenclature and attendant meanings need to be carefully examined in their sociohistorical context, particularly when race is evoked outside its traditional setting of Western intellectual frameworks and illustrative contexts.

I have discussed elsewhere the descriptions of race and related terms (such as jinshu, minzoku, and shu) in school textbooks during the first half of the Meiji period1. In this article, I flesh out my examination of these various descriptions, including ones denoting minoritized groups in Japan and the Japanese Empire, and covering a longer period, through to the end of the Meiji period. The topic of “race” attracted greater attention than other topics such as language and religion in textbooks on foreign geography, especially during the first half of the Meiji period.

School textbooks, exerting the utmost influence on children and students, reproduce knowledge through the public education system. A number of case studies on descriptions of race in North American and European textbooks have shed light on the significant role they play in the construction of the idea of race and on assimilation policies imposed on indigenous peoples2. Examining race-related terminology in Japanese school textbooks during these periods corroborates case studies conducted in Western societies and their former colonies, while also providing fresh insight into the role textbooks play in constructing race. To the best of my knowledge, there is no research which specifically analyses race and related terms in textbooks used for nationwide school education during the Meiji period3.

Through a diachronic examination of nearly 70 textbooks used during the Meiji period, in addition to several geography books published around the turn of the Meiji period and other related material, this article elucidates their race-related content to demonstrate how the Meiji government employed race as part of its project of empire expansion. The article explicates the processes by which knowledge was produced and circulated during and around the Meiji period, and demonstrates how discourse involving these terms subsequently acquired a transformative turn amidst domestic and international instability.

Historical Background: Prior to the Meiji Restoration

Firstly, examination of the history of the original meanings attached to the Chinese compound “人種,” in both China and Japan, shows them to have changed drastically over the periods under study. The Chinese compound “人種,” today pronounced jinshu, meaning “race”, dates to (at least) the fourteenth century. For instance, it was used in Shintōshū, a medieval text (c. 1358), to mean “the seed of humankind”, or simply “humans.”

While skin color would later come to be an index for racial classification, it was not what initially drew the attention of the Japanese when they first encountered Europeans in the mid-sixteenth century. Figure 1 depicts an artist’s impression of a group of “Nanban” (lit. southern barbarians, the name used at the time to refer to Westerners, specifically the Portuguese and Spanish) arriving in Japan in the late sixteenth century4. It is noteworthy that the European men’s skin appears essentially identical to that of the Japanese men, while the Japanese women inside the building are paler than either. Here and in the other Nanban screens I have examined, the physical characteristics the artists emphasized were, rather, the European’s prominent noses, beards, and tall height.

Nanban Screen (right wing). Designated as an Important Cultural Property.

Painter Unknown. Between the end of the sixteenth century and the beginning of the seventeenth century.

Other foreigners include sailors and servants, depicted in the screens as black and grey respectively, depending on whether they hailed from Africa or from South or Southeast Asia. The fact that the first Africans and south or southeast Asians whom Japanese encountered were subordinate to Europeans probably also influenced later prejudice against them.

This image differs little from depictions of the Dutch, who, after the suppression of Christianity, were the only Europeans allowed into Japan during the Edo period. For example, the following description of Italian missionaries in Seiyō kibun (Tidings of the West, 1715) by the well-known mid Edo-period intellectual and politician Arai Hakuseki5, closely matches such depictions:

They are tall of stature, standing well over six feet; the average person does not even reach their shoulders. They keep their black hair cut short, their eyes are deep-set, and their noses prominent. They wear dark brown narrow-sleeved padded jackets, woven from Japanese silk6.

Arai notes first their height, then the style and color of their hair, the shape of their eyes, the size of their noses, and the style of their clothing, but he does not once mention the color of their skin.

This sort of fragmentary information about Western nations and peoples made its way into intellectual and samurai families of the late Edo period in the form of cultivated education acquired via Christian missionaries and Rangaku, or Dutch (i.e., Western) learning7. Exactly how, when, and by whom the modern Western reading of it, which is used to denote the conceptunderstanding of race and human classification, i.e. “race”, was introduced to Japan during the Edo period remains unknown. Nonetheless, it presumably accompanied other Western learning reaching Japan via Christian missionaries and Dutch learning.

As it happens, Dutch learning of the Edo period also conveyed French language and culture to Japan. For example, the Lyonese monk Noel Shomel’s Hyakka zensho (Complete Encyclopedia), first published as a two-volume set in 1709, was widely read during the eighteenth century8.

The first Japanese intellectual to discuss人種 as the translation for “race”, and European human divisions more generally, is Watanabe Kazan, a late Edo period painter, man of letters, and devotee of Dutch learning. In Shinkiron (A Private Proposal), published in 1838, thirty years before the Meiji Restoration, he draws on the ideas of Linnaeus and Johann F. Blumenbach to present four categories for dividing humankind: “Tartar”, “Ethiopian”, “Mongolian”, and “Caucasian”9. He states, “All the five continents on the earth with the exception of Asia belong to Europe”.

At the period Kazan was writing about foreign affairs, Russia, England, and America emerged as threats to Japanese sovereignty. In 1806 and 1807, the Russians attacked the shogunal army’s northern bases on the islands of Sakhalin (Jp. Karafuto) and Iturup (Jp. Etorofu). At the same time, English ships were appearing in Japanese waters, repeatedly making illegal landfall and clashing with local fishermen. In his Gaikoku jijōsho (On Matters Foreign), Kazan writes: “I have heard the English have found an island close to Japan and landed there”10. In another book, he notes: “within Asia, only the three countries of China, Persia, and our country have avoided the ‘defilement of Westerners’”11. This passage demonstrates Kazan’s growing anxiety about the future of Japan, his gaze turned overseas to Europe’s expanding colonialism in Asia, its shadow encroaching over Japan.

Superseding the premodern meaning of 人種, and taking root even as it was wholly transformed in its new context, this new concept of jinshu, classifying humans into different races on the basis of visible phenotypical traits, such as skin color, first reached Japan via Europe and later the United States. The English and French word “race” and the German “Rasse” each have a number of definitions, therefore there is no single Japanese translation that can accurately capture the original “race”, as its meaning varies depending on the context of its source. Discussion of human classifications, however, almost always used the word jinshu 人種 as a general translation of “race”.

In earlier Chinese writings, the compound 人種 had the meaning of “bloodline” or “blood lineage”. This is exemplified in a sentence in Jingkangzhuanxinlu, originally published in 1127, referring to the bloodline of the Chinese emperor which, it contends, would be extinguished. Nevertheless, my survey of classical Chinese texts in China between 1750 (around the time of the first publication of Blumenbach’s dissertation) and 1840 (shortly after the publication of Watanabe Kazan’s Shinkiron in Japan) found no examples of the word being used to refer to divisions of humankind12. It is widely known that the Chinese terms renzhong 人種 and mínzú 民族 were introduced into Chinese from Japanese, along with other terms associated with Western science and civilization, by Liang Qichao and many other Chinese intellectuals who studied in Japan in the early twentieth century.

The early Edo period had seen the advent of temple schools which dispensed elementary education. Their numbers rose dramatically in the nineteenth century, such that by the end of the Edo period there were an estimated 30,000-40,000 temple schools throughout the Japanese archipelago13. As noted elsewhere, this resulted in literacy rates in Edo Japan as high as those in parts of Europe14.

In 1853, US Navy Commodore Matthew Langford Perry came to Japan with four massive black battleships to press the Tokugawa shogunate into opening the country, which in the following year resulted in the end of more than two hundred years of isolationist policy. Thereafter, a large number of Japanese intellectuals traveled to the United States and to Europe to acquire Western knowledge, including theories of race.

The First Decade of the Meiji Period (1868-1877)

In 1868, the Meiji Emperor, who regained the Imperial Rule back from the shogunate, started what is now known as the Meiji Restoration, a series of reforms centered around policies of industrialization, enriching the nation and strengthening the military, and so-called “civilization and enlightenment” Of Japanese society. One measure into which the Japanese government poured a great deal of energy was the nationwide propagation of elementary education. In accordance with the Great Council of State’s (Daijōkan) Meiji 5 (1872) proclamation, the government set about establishing at least one elementary school in every school district in Japan.

Europe and America provided the template for the Meiji government’s policy of Bunmei Kaika (civilization and enlightenment), as, to their eyes, modernization equated to Westernization. For the Japanese authorities, it was thus imperative that the textbooks produced for their new school system be similar in content to those used in the West.

After the Meiji Restoration, even Japanese elementary-school education actively promoted the ideology of “leave Asia and join the West”. Discussing the characteristics of early-Meiji geography textbooks, Nakamura Kikuji notes: “The pre-Restoration reverence for China vanished completely, to be replaced by a powerful interest in the West and consequently a prejudiced and contemptuous view of Asia, and of ‘Shina’ in particular”15.

It required some years to prepare school textbooks to reflect the major shift from the Shogun-led Edo system to the Emperor-led Meiji government. Creating comprehensive material was an enormous task, so during the first decade of the Meiji period the vast majority of textbooks were based on translations or adaptations of texts imported from Europe and America. This period is accordingly referred to, in the history of Japanese education, as “the translated textbook era”.

Japanese intellectuals made significant strides, translating a vast number of Western books between the late Edo period and the beginning of the Meiji period, particularly between the 1850s and 1870s16. Geography was considered a particularly important subject in the eyes of the Ministry of Education. According to the “Charter of Regulations for Elementary Education” promulgated in Meiji 5 (1872), reading geographical names was to be introduced at Lower Division Level 5 (7 ½ years old) and round-table geography reading at Level 3 (8 ½ years old); from Level 3 through to Upper Division Level 1 (13½ years old), more time was devoted to geography than to any subject other than arithmetic and calligraphy17.

Due to the small number of geography books produced in Japan at the time, the “Regulations for Elementary Education” (shōgaku kyōsoku) designated five geography textbooks. Three were primarily composed of translations from foreign geography textbooks, while the remaining two dealt with Japanese domestic geography. Sekai kunizukushi, a million-copy bestseller of the time, and Yochishiryaku, of which one hundred and fifty thousand copies were printed by 1874–1875 (and more later with new editions), both exerted an enormous influence. Their passages on race and related topics became the models for other early Meiji world geography textbooks.

Uchida Masao, the author of Yochishiryaku, was a Ministry of Education bureaucrat who had collected Western textbooks and geography books at the end of the Edo period while studying abroad in the Netherlands and later travelling around the world. Yochishiryaku18 is partially based on entries in Tour du Monde: nouveau journal des voyages, a popular French travel journal published in the middle of the nineteenth century, with almost half the illustrations in his book copying those in this weekly19.

Gōrudosumisu, credited by Uchida in his “Introduction” as the author of one of the main works he consulted in writing Yochishiryaku, refers to the London-based missionary J. Goldsmith (whose real name was Richard Philips), the author of A Grammar of Geography for the Use of Schools, with Maps and Illustrations—a series of geography textbooks widely used in English elementary schools20. Goldsmith’s original book in English describes the approximate populations of the world’s five continents under the heading “Race Categories”, with details of the inhabited area, population, physical characteristics, and the stages of civilization of the “five races”: Mongolian, Caucasian, Ethiopian, Malay, and American21. Yochishiryaku likewise discusses the stages of civilization: It lists China, Siberia, and Turkey as “half-civilized” countries, and European countries and the United States as “civilized” countries. It defines “half-civilized” countries as having a constitution, land de-privatized by a sovereign, and so on.

Fukuzawa Yukichi, the author of Sekai kunizukushi, also collected Western books during his travels abroad at the end of the Edo period. Although he does not list the titles of the books he consulted, Fukuzawa states in his explanatory foreword that he selected and translated only the “important parts of world geography and history books already published in England and the US”, emphasizing that “therefore, none of my own proclivities are included”. This reflects the contemporary background, in which translation-based textbooks “received higher evaluations, being the education of civilization, and being new books”22.

In Sekai kunizukushi, Fukuzawa divides humankind into four categories: “chaos” (konton); “barbarian” (ban’ya); “as yet uncivilized (mikai) or half-civilized (hankai)”; and “civilized” (bunmeikaika). The “most inferior people”, “Chaos”, were described as those who sometimes “eat human flesh”, fight each other, and are illiterate, lawless, and unmannered. “Natives” (dojin) of Australia and inner Africa were presented as examples. “One stage above savage people” were the “Barbarians”, represented by the Tartars living in northern China, and “natives” of Arabia and north Africa. Chinese and some other Asians were considered “as yet uncivilized (mikai) or half-civilized (hankai)”. Finally, “civilized” (bunmeikaika) people were described as those who value manners, are moderate in their emotions, and actively engage in academic work, the arts, and farming. The United States, England, France, Germany, and the Netherlands were presented as ideal examples23. Fukuzawa proclaims:

“Dividing the world into five races, their levels of intelligence are not the same, and likewise countries’ customs and industry are not the same”24.

The ideas about the stages of civilization presented in Sekai kunizukushi became the basis for discussions that appeared in other Japanese geography textbooks, often in a section on the “Stages of Civilization” (bunmei no tōkyū) comprised of sub-sections such as “Barbarian”, “Savage”, “Half-Civilized”, and “Enlightened”. Each sub-section included a rudimentary definition of the respective stage, and the names of several countries presumed to provide examples for visualizing the kinds of people comprising each category.

Straying from the convention in Western textbooks, Asia was accorded a central place in the first volume of Fukuzawa’s series, which includes many descriptions and illustrations of China and the Chinese. In his discussion of China’s defeat by the British in the Anglo-Chinese War, which resulted in indemnity payments and the transfer of Hong Kong to Britain, he argued that China “in the end earned the contempt of other countries, because there were truly no people who held patriotic thoughts”25.

With the encroachment of Western powers, Fukuzawa felt it urgent that women and children be educated and thereby encouraged to cultivate a patriotic spirit. Fukuzawa believed there were two possible outcomes for Japan: it could either succumb to the same fate as China, or it could attain the same level of civilization as Western nations. For Fukuzawa, Japan’s future depended on whether common people–especially children, the country’s future, and women, responsible for raising them–would take an active interest in the arts, sciences, and learning in the home. Fukuzawa explained his motivation for translating and introducing these descriptions into Japan as follows:

“It can be easily imagined that the source of fortune and misfortune under heaven is nothing other than the intelligence and stupidity of the people. It is my sole hope that this book Sekai kunizukushi makes mainly children and women understand the formation of the world, opens the door to this knowledge, and thereby establishes the basis of welfare and happiness under heaven.”

At the time, translations of foreign textbooks were “highly regarded, as they represented the education of enlightenment and civilization”26.

Teacher-training colleges were established with the promulgation of the educational system in Meiji 5 (1872), at which point geography was included in the curriculum.

From the right:

White Race, the First Grade; Yellow Race, the Second Grade; Black Race, the Third Grade.

Kyoto University Main Library.

Horikawa Kensai, Chikyū sanbutsu zasshi, Global Products Compendium, 1872.

Figure 2 is “An Illustration of Racial Classification,” in Chikyū sanbutsu zasshi (Global Products Compendium) (M5/1872), translated from a book by Eugène Cortambert, a French geographer. The upper labels read from right to left: Hakushu (White Race), Ōshu (Yellow Race), and Kokushu (Black Race), and the labels below the illustrations read: Dai-Ittō (The First Grade), Dai-Nitō (The Second Grade), and Dai-Santō (The Third Grade). While the French author appends “Malay”, “Polynesian”, and “American” to the list of “general races”, yielding “six racial classifications” in all, the three enumerated above are considered “the most fundamental”. Among these, he positions the white race as preeminent: “They are the cleverest and most audacious in their skills, and as such are held at present to be the most advanced civilization”. He goes on to say that “the members of [the yellow race] who live to the east have been civilized since ancient times, but those to the north are as yet barbarian in their customs”, evidently discriminating between the level of civilization in China and Eastern Japan on the one hand, and northern Asia on the other27.

In M7 (1874), the Ministry of Education published Hyakka zensho Jinshu-hen (An Encyclopaedia, Volume on Race), a translation of “Physical History of Man – Ethnology”, a chapter in Chambers’s Information for the People, an English textbook in wide use in Europe and America28. It draws on the work of leading scholars of race at that time, such as Johann F. Blumenbach (Germany), Georges Cuvier (France), James Cowles Prichard (Britain), and Daniel G. Brinton (United States). The book served as a guide for school teachers and a model for discussions of race in Japanese textbooks, resulting in the spread of the word jinshu in Japan.

In the geography books I examined, the section on “Racial Distinctions” occupies a prominent place in nearly all those that had been translated and published during the first ten years after the Meiji Restoration, regardless of country of origin. This section tended to appear at the beginning, following discussion of world population. While the translated texts rarely provide the publication years and titles of their sources, their forewords and explanatory notes allow us to deduce that the most frequently used source texts were the American geography textbooks by Cornell and Mitchell, and the British geography textbooks by Goldsmith.

In addition to those listed above, the teacher-training college’s Elementary School Reader (Meiji 6) is another representative example of early-Meiji translated/adapted textbooks. It was reprinted throughout much of Japan until Meiji 18, becoming so widespread that a survey of the circulation per prefecture of Ministry of Education textbooks, published in the Ministry of Education Magazine, ranked it second, only exceeded by the Glossary. Volume 1, chapter 1 of the Elementary School Reader begins with the following, which elementary school students were expected to recite from memory: “Broadly speaking, there are five types of people living in the world: the Asian race, the European race, the Malay race, the American race, and the African race. The Japanese are part of the Asian race”. According to Nakamura, the illustration accompanying this passage comes not from the original textbook by M. Wilson on which the Reader is based, but probably from High School Geography (1860) by S. S. Cornell (Figure 3). In the Elementary School Reader version, however, the Chinese have been replaced with the Japanese, and the position and attitudes of the five races have been altered (Nakamura 1984: 58). Cornell’s illustration of the five races was also repurposed for Fukuzawa Yukichi’s On Matters Western – Volume 1 (Keiō 2) (Figure 4).

On the left: Illustration of Five Races in High School Geography (1860) by S. S. Cornell

On the right: Illustration in Fukuzawa Yukichi’s On Matters Western (1866)

During the early Meiji period, which extolled civilization (bunmei), geography textbooks focused greatly on “civilized” European countries. It is interesting to note that although Japanese intellectuals viewed the Japanese as more civilized than the Chinese, their writings on the stages of civilization, based on Western textbooks, failed to clearly place Japan in the category of the civilized or that of the half-civilized (a category used to describe China and certain other Asian countries). Consequently, the readers of these books remained for the most part unaware of Japan’s position, from a Western viewpoint, in the different stages of civilization.

The Second Decade of the Meiji Period (1878-1887)

The earlier translated texts continued to set the tone in the beginning of the second decade of the Meiji period. Bankoku chirishi (World Geography), published in 1877 (Meiji 10)29, lists “Augustus Mitchell’s school atlas (Model Geography), with excerpts translated from Harper’s American geography text, Goldsmith’s English geography text, and others” as its sources of information (note to the reader). Likewise, World Geography Guidebook (Meiji 11)30 was also published as a “translation”. Both use a five-part “racial classification” based on Blumenbach, and both list four “degrees of civilization” as barbarian, savage, half-civilized, and enlightened, with definitions and examples given for each. This is expressed symbolically in the title of World Geography Guidebook as well: the word kaitei, “guidebook”, can also mean “rank or gradation”.

Textbooks from around the middle of the second decade of the Meiji period started to reflect Japan’s domestic circumstances, with the educational system beginning to move away from texts which were mere translations of Western originals. The contents of these textbooks were intended to awaken an interest in geography by, for example, proclaiming the importance of “studying the customs and manners of the blue-eyed, red-bearded Westerners, ‘pig-tail’-wearing Chinese, and other foreigners who come and go from our ports and places of international trade”31.

With the “General Regulations for Elementary Education” adopted in Meiji 14, the introduction of geography was moved to mid-level elementary school. In terms of content, students began with the geography of the area surrounding their school, then move on to studying first the geography of Japan, and then the rudiments of the geography of other countries. In upper-level elementary school, the students studied such things as the Earth and its surface, biology, and the primary products of various nations.

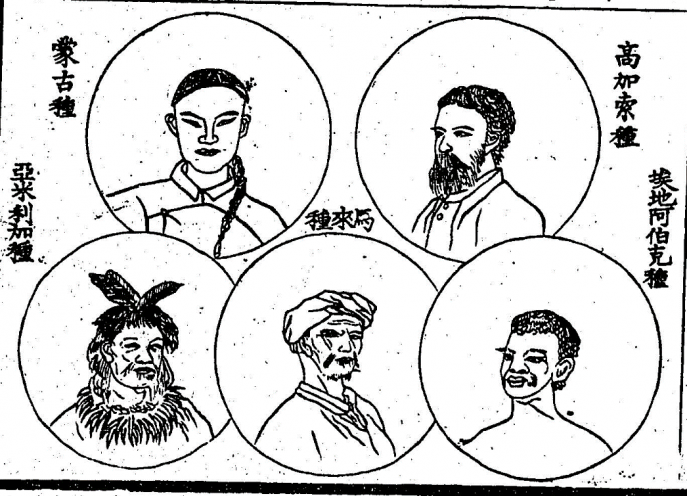

Bankoku chishiryaku, Shukan, Chiri sōron (Abridged World Geography Volume 1 – Introduction to Geography, Meiji 15) divides humanity into five races, accompanied by the following illustration (Figure 5)32.

Figure 5: From upper right to left: Caucasian, Mongolian. From lower right to left: American, Malay, Ethiopian, in Bankoku chishiryaku, Shukan, Chiri sōron (Abridged World Geography Volume 1 – Introduction to Geography), University of Tsukuba Library, Meiji 15.

Textbooks published from Meiji 10 to Meiji 20 reflected a shift towards a Japan-centric view, both of the world at large and of the country’s domestic social predispositions. As “the number of countries with whom Japan enact[ed] treaties and trade continue[d] to increase,” there was heightened interest in learning about the disposition and customs of the many Westerners and Chinese who could now be seen in Japan’s port towns. The section on “race” in Chigaku shinpen (Geography – New Edition) (Meiji 22) begins: “Have you ever seen a Westerner? Their hair is yellow, their skin is pale, their eyes are deep-set, and their noses are prominent”. We can therefore assume that by this date, the chances had increased for the average person to see Westerners or Chinese people, at least in some areas of Japan33. Bankoku chishi (World Geography) (Meiji 24), likewise, mentions the “foreigners taking up residence in places like Yokohama and Kobe”34.

The Meiji 10s brought new demand for independent Japanese pedagogy. Geography education was infused with patriotism via the notion of the “one unbroken line”, in an attempt to strengthen the foundations of an emperor-centric nation-state. For example, Shinsen chiri shōshi (Newly Compiled Geography Pamphlet, 1879) includes the phrase, “The emperors of Japan are one unbroken line (bansei ikkei)”35. Similarly, the authors of Yochishiryaku (1879) assert there had been 123 generations of emperors since Emperor Jinmu36.

Listed as a source text in Bankoku chirishi (1877) and other textbooks, Haruperu-shi no chishi (Mr Harper’s Geography Textbook) appears to refer to Harper’s School Geography, With Maps and Illustrations37. In the 1878 and 1886 editions of Harper’s, “Conditions of Society” proposes dividing people (and their respective nations) into five stages based on their “social condition”: savages, barbarians, half-civilized nations, civilized nations, and enlightened nations. Here, the concept of “enlightened” is added as a separate stage to that of “civilized”. They are distinguished in the following way:

“Civilized nations are those that engage in commerce, practice the art of writing, and have made considerable progress in their knowledge and morality. Enlightened nations are those civilized nations that possess a thorough division of labor, have established general systems of education, and have made the greatest progress in knowledge and morality38.”

Immediately after these definitions, it states: “The enlightened and civilized nations are nearly all Caucasian”39. Again, there is no mention of Japan’s place in this gradation.

It is noteworthy that my research found no passage in early Meiji geography textbooks containing the word minzoku as a translation of “race”.

The Third Decade of the Meiji Period (1888-1897)

The establishment of the Meiji nation-state in the Meiji 20s was an important turning point in the history of modern Japan. The Constitution of the Empire of Japan was promulgated in Meiji 22 (1889), with the first session of the Imperial Diet, and the impending Imperial Rescript on Education the following year. The First Sino-Japanese War broke out soon after in 1894 (M27), and ended the next year.

From this decade onward, there was as shift in approach to teaching geography focusing on the prosperity and strength of the state. This was outlined explicitly in the 1891 “Fundamental Principles of Education”. In particular, its moral training curriculum emphasized “working to foster respect for the Emperor and a spirit of patriotism, and laying out the essentials of one’s duty to the nation”. On the subject of Japanese and foreign geographies, it prescribed “teaching the essentials to create an understanding of the important aspects of the life of the people, while fostering a spirit of patriotism”.

This emphasis on the importance of fostering a patriotic spirit marked the emergence of a new trend, different from that in the early Meiji period. Under the “Fundamental Principles”, geography education was repositioned: “Geography must teach first the oceans, the continents, and the five climatic zones, and then the topography, climate, products, and races of each continent, and provide the knowledge of the basics of the geography of China, Korea, and any other countries in important positions vis-à-vis Japan” (Ministry of Education 1891).

Here, “race” is afforded the same importance as topography, climate, and national products. Moreover, teaching the basics of the geography of countries relevant to Japanese interests, including China and Korea (both of which would soon be partially under Japanese colonial rule), was perceived as having a connection to the aforementioned fostering of patriotic spirit.

During the early Meiji period, most geography textbooks were foreign books translated into Japanese, but Middle School World Geography (Meiji 29) criticized such books as “meant for Western pupils, and not appropriate for the pupils of our nation”. It instead proposed a new approach: “Rather than studying the various countries of the world, [our students] should learn the ways in which our empire is superior to them, and by studying its features, learn how beautiful its natural and geographical features are, and how gentle its climate is”40. Note here that the study of world geography shifts its emphasis from gaining knowledge of foreign countries to recognizing the “superiority” and “beauty” of Japan.

This aggrandizement of patriotic spirit was reinforced by the discourse about “lineage” in books such as Political Geography of the Japanese Empire (Meiji 26): “The races of our empire all have their origins in the same Japanese lineage, and so come together in the concept of the Japanese people”41.

The Meiji 20s saw the adoption of a model that differed from that of the early Meiji period, which had been centered around Blumenbach’s classification of the races of the world into five groups. This new model saw the “Aryan Race” explicitly situated as a part of the “Caucasian Race”42. Unlike the translated works of the early Meiji period, which had cited their sources, albeit incompletely, the textbooks of this period did not provide clear references for the sources used to define the Aryan Race, nor for the term itself. What is clear, however, is the influence of late-nineteenth-century European race studies, which further subdivided and stratified the European race. As it happened, it was also in Meiji 28 that the economist, historian, and member of the Lower House Taguchi Ukichi presented his “On the Japanese Race,” which employed linguistic evidence to assert that the Japanese people belonged to the Aryan language family43.

As described above, early Meiji textbooks have few or no references to the stages of civilization and enlightenment of the Japanese people themselves. Yet, the Meiji 20s saw the emergence of texts which, departing from European racial theories centered on Blumenbach and Cuvier, described the Mongolian or Japanese races as equally enlightened and civilized as the Caucasian race.

“[After positing a five-fold racial classification including the Asian Race, the European Race, etc.] While the Europeans and Asians are the most intellectually advanced among the five races, and are either civilized or half-civilized, the other three races are generally ignorant and the people largely uncivilized or barbarian44.”

“[Among the yellow races,] we Japanese and the Chinese are the most advanced.”

“[The white race] includes some nations that are intellectually superior and the most vigorous in the world45.”

As we can see from the above quotations, books in which the “Chinese” were situated alongside the Japanese at the pinnacle of the Mongolian Race existed side-by-side with the openly self-aggrandizing ones in which Japan boasted of its own superiority or beauty.

“The likes of China, India, and Persia had great civilizations in ancient times, creating great things which neighboring countries also enjoyed, and producing indomitable heroes one after another [...]. But in recent times their power has waned [...]. Now it is our great nation of Japan alone, as a constitutional monarchy of unbroken imperial lineage, whose power increases day by day, whose culture advances month by month, and whose national polity is well equipped46.”

“Those of the Caucasian and Mongolian races, who live in the temperate zones of the northern hemisphere, are the most civilized, vigorous...47”

Thus, many textbooks positioned Japan as the top “Yellow race”, emphasizing its superiority relative to the other peoples deemed part of that same race48. By rejecting the clear binary opposition of “white races vs. colored races”, seen as self-evident in Europe and America, and grouping together the “Caucasian race” with the “Mongolian race” (“Asian race”), a newly re-formulated interpretation posited the existence of these two races and “the other three races”.

There had already been arguments tying race to degree of civilization in the early Meiji period, and this trend continued into the Meiji 20s. For example, the following quote from Elementary School World Geography, volume 1 shows that the classification into “four stages” in Western textbooks imported during the early Meiji period was carried over into this period:

“In comparing the state of intelligence and civilization of the people of the various countries of the world, we can roughly divide their level of progress into the four stages of civilized, half-civilized, uncivilized, and barbarian49.”

“Within the five races, the two races of Europe and Asia are advanced in their knowledge and are civilized or half-civilized, while the other three races are generally ignorant and unenlightened, with many of their people being uncivilized savages50.”

At the beginning of this section on “race (jinshu)”, after positing that the appearance of the Chinese is not so different from “our own” [the Japanese], it goes on to say: “And have you ever seen a Westerner? Their skin is pale, their noses prominent, and their appearance generally unlike our own”. Here “pale” skin color and “prominent” noses are given as examples of racial characteristics51.

It was in the late 1880s that “minzoku” started to appear and circulate in its contemporary sense52. The founding of the magazine Nihonjin (The Japanese) and the newspaper Nihon (Japan) in 1888, six years before the outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895), helped disseminate the contemporary meaning of the term minzoku (“nation,” “ethnic group” or “people”) across the country. The denomination minzoku, at least at its inception, was inseparably related to the Japanese “nation” and “nationalism”.

The Fourth Decade of the Meiji Period (1898-1907)

The Ministry of Education revised the law governing elementary schools again in Meiji 33, ordaining compulsory education at public elementary schools free of charge, leading to attendance rates topping 90%53. However, 40% of elementary school students either failed or withdrew without graduating, with many dropping out before completing their compulsory education due to their families’ finances. This new law designated geography as an upper-level elementary [= middle school] course, removing it from the regular elementary curriculum. The Teacher’s Education Law of Meiji 30 established the Geography/History section as part of the main curriculum for teacher-training colleges, forming the prototype for education in geography. While Japanese and foreign geography had been treated independently under the Meiji 23 Elementary School Law, here they were combined into a single “geography” class.

Climate and Civilization

Alongside attributes such as external appearance and language, climate became an additional factor for classification. The following passage from the Meiji 34 textbook New Mid-Level Geography – Foreign Countries demonstrates the belief that alongside differentia like innate intelligence and level of civilization, climate is also an important determinant of reproductive capacity:

“Racial reproductive capacity is governed not only by natural intelligence and climate, but also by degree of civilization, individual constitution, societal customs and cultural practices.”

Likewise: “in temperate climates, hard work is always rewarded with a proportionate result, as mind and body develop in tandem, with energy to spare for the arts and learning54”.

As of the middle of the Meiji 20s, climate was linked to race, with longer passages appearing in the Meiji 30s55:

[After listing the five races (Caucasian, Mongolian, “Ethiopian,” Malay, and American)] “A moderate climate is the habitat most suited to the full realization of the human race’s reproduction and development [...]. It goes without saying that the subtropics are just such a place, and indeed most civilized and enlightened nations live in these latitudes56”.

In such texts, race is said to be closely linked to climate, and the temperate zones depicted as the most favorable for the reproduction and growth of the human race. They state that most civilized and enlightened peoples in fact live in temperate zones, and assert that, because the Japanese live in a temperate climate like the people of Western Europe and the United States, they must therefore be similarly civilized and enlightened.

We can also find passages that take Japan’s form of government as proof of national advancement: “Ours is the only nation to boast an autocracy, even among the great nations of Europe57”.

Minorities and Imperial Rule

In the Meiji 30s, after the First Sino-Japanese War, heightened nationalism and Yamato-supremacist thought filtered through to descriptions of the minorities under Japanese imperial rule, namely the Ainu, Ryūkyū Islanders, and the peoples of Taiwan. The following is from the Meiji 34 textbook Middle School Geography of Our Nation:

“While the inhabitants of our nation all belong to the yellow race (jinshu), they can be divided into the following five racial groups (shuzoku) according to their language, customs, disposition, and appearance: The Yamato Race (shu), the Ryūkyū Race, the Ainu Race, the Han Race, and the Taiwanese Race58”.

In other words, while they are of the same jinshu, their shu depends on their respective language, customs, appearance, and so forth, therefore positioning shu as a subordinate concept to jinshu. The text goes on to praise the “Yamato Race59”.

The book is openly contemptuous of the Ainu: “While daring by nature, they are an ignorant and uncivilized race (shuzoku), and are rather to be pitied60”. On the “Ryūkyū Race,” however, the text withholds judgement: “Racial science has not yet been able to determine whether or not they are a separate race”. As for the “Han Race”: “They reside in Taiwan, largely having come over from the Fujian and Guangdong regions during the Ming dynasty”. The “Taiwanese aborigines”, by contrast, are described as follows: “Their customs and practices are little different from those of the Chinese, and the wild tribespeople are largely savage and bloodthirsty61”.

The textbook Mid-Level Elementary Geography: Japan (Meiji 33)62 also touches on the Ainu, Taiwanese, and Ryūkyū Islanders along with the Yamato Race. As we can see, this text differentiates the Taiwanese, Ryūkyū Islander, and Ainu races under Japanese imperial rule from the powerful Yamato Race. It suggests that in being conquered by the Yamato, these other races have altered their customs, becoming almost the same race.

“An Introduction to Geography” in General Education Geography Textbook describes “the Indo-Germanic Race (shuzoku)” as “the race with the most advanced civilization,” while stating that the Mongolian Race’s “characteristic civilization did at one time reach great heights, but they have now fallen a step behind the Caucasian Race [...] and it is to this [Mongolian] race (jinshu) that our Yamato people (shuzoku) belong63”.

In this way, the scholarly notion of ranking civilizations in terms of their relative superiority or inferiority, imported during the early Meiji period, was transformed into a means of justifying the colonial control of minority populations within the Japanese empire64.

The Fifth Decade of the Meiji Period (1908-1912)

In 1910 Japan gained exclusive colonial control of the Korean Empire beginning through the Treaty of Portsmouth (1905) that ended the Russo-Japanese War. Thereafter, Japan continued the expansion of its colonial rule through military invasion in the surrounding nations of Asia. The following phrase that praises the Empire of Japan appeared in Upper-Level Elementary Geography Volume Two (1912)— “Blessed with an Emperor of unbroken lineage at its head, and abounding with a spirit of loyalty to one’s lord and love for one’s country65”.

Japanese intellectual historian Shin’ichi Yamamuro points out, a “discourse of East-West harmony” aimed at both the West and the East appeared in Japan after the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-1905, and some began to tout the idea that Japan had a mission to enlighten the rest of East Asia in its capacity as the leader of Asian civilization66. This paternalistic idea that Japan had a mission to bring civilization to the rest of Asia was a colonialist mentality, and an imperialization movement to turn the colonized peoples of Taiwan and Korea into subjects of the Japanese emperor followed.

“Ethnicity (minzoku)”

The word minzoku is virtually absent from geography textbooks written in the first half of the Meiji period, but it does appear in An Introduction to Geography (Meiji 36)67: “It is to this race [the Mongolian Race] that our Yamato people (minzoku) belong” (17)68.

Although it is beyond the scope of this article, it is worth pointing out that from the Russo-Japanese War (1904-1905) through to World War I, Japanese aggression within Asia and the expansion of the Japanese empire proceeded in tandem with a marked increase in the number of pages devoted to foreign geography in Japanese textbooks69.

From “Leave Asia, Enter Europe” to the Construction of the Japanese Empire

This article has examined descriptions of race (jinshu) and related terms in Japanese geography books and textbooks from the late Edo period through to the end of the Meiji period. It has elucidated transformations in their content about foreign geography, as well as in the roles they played: works similar to the imported scholarship in the early Meiji period underwent a radical change as the Japanese empire expanded from the middle of the Meiji period onward.

After the First Sino-Japanese War, Japan started to nurture a sense of its superiority, not just vis-à-vis China but throughout Asia. Wang Ping, who has written about the changes in Japan’s view of China, argues that Japan’s victory in the First Sino-Japanese War was a watershed moment: “[After the war,] it was a simple matter for Japan to replace the model of ‘Civilization = the West vs. barbarian = the East’, with ‘Japan = civilization = the West vs. China = barbarian = the East’70”.

Throughout the Meiji period, the racial dichotomies and positionings described in textbooks demonstrate a major shift in Japanese epistemologies about race: the original “white races vs. colored races” dichotomy became “the white and Mongolian Races vs. other races”, then “the white race and the Chinese and the Japanese race vs. other races,” and finally “the white race and the Yamato race vs. all other races”.

These concepts were later used from the mid-Meiji period to gauge power dynamics between Japan and other countries, and to instill the idea that the Japanese had reached an equal level of civilization to white people. At the same time, they served as a central tool for strengthening colonial control over other areas in Asia and over the surrounding minority peoples such as the Ainu, the Ryūkyū people, and the indigenous peoples in Taiwan, whilst mobilizing discourses about the imperial family and Japanese bloodline to increase ethnic and national awareness.

In Japan, the concept of “race (jinshu)” was interpreted and transformed into the supposed stages of civilization, thus becoming a non-physical, invisible marker. The highest stage was seen as attainable by lower-ranked countries – especially Japan. Skin color and head shape, visible essential markers and devices used to justify colonialism in Europe and the United States, were replaced with the invisible index of “civilization”.

Notes

1

Yasuko Takezawa, “Translating and Transforming ‘Race’: Early Meiji Period Textbooks”, Japanese Studies, 2015, 35(1), p. 5-21.

2

For example, see Christine Rogers Stanton, “The Curricular Indian Agent: Discursive Colonization and Indigenous (Dys)Agency in U.S. History Textbooks”, Curriculum Inquiry 2014, 44 (5), p. 649-676; J. A. Mangan, The Imperial Curriculum: Racial Images and Education in the British Colonial Experience, London and New York, Routledge, 1993(2012); Marta Araújo and Silvia Rodríguez Maeso, “History Textbooks, Racism and the Critique of Eurocentrism: Beyond Rectification or Compensation”, Ethnic and Racial Studies, 2012, 35(7), p. 1266-1286; M. Spearman, Race in Elementary Geography Textbooks: Examples from South Carolina, 1890–1927, edited by C. Woyshner and C.H. Bohan, Histories of Social Studies and Race, New York, Palgrave and Macmillan, 2012, p. 115-134; Gilmer Blackburn, Education in the Third Reich: Race and History in Nazi Textbooks, Albany and New York, SUNY Press, 1985; A. M. C. Maddrell, “Discourses of Race and Gender and the Comparative Method in Geography School Texts 1830–1918”, Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 1998, 16(1), p. 81–103.

3

Most of the material examined in this article is from the Rare Books Collection held at the University of Tsukuba (formerly the Tokyo Higher Normal School), Kyoto University Library, the Textbook Research Center (Tokyo), and the National Diet Library Modern Digital Collection.

4

The Chinese character for “ban” originated from China. It was used to referred to others in relation to the four cardinal directions. Since these Europeans came from the south on ships, they were called nanban.

5

In this essay, the name order of Japanese historical figures uses the Japanese style according to which the surname preceded the given name, whereas all remaining Japanese names follows the Western style.

6

Arai Hakuseki, “Seiyōkibun” (Tidings of the West), in Mishima Saiji ed., Nanbankibunsen (A Nanban Anthology), Tokyo, Shūhōkaku, 1926 (originally published in 1715), p. 7-8.

7

Rangaku, or Dutch learning, refers to the study of knowledge acquired through the Dutch traders staying in the Dejima area of Nagasaki and to books translated into Japanese, providing Japan the window to Western knowledge, especially of science and medicine.

8

Takahashi Kunitarō, “Oranda wo tsūjite inyū sareta Furansu bunka”, in Ogata Tomio ed., Rangaku to Nihon bunka (Dutch Studies and Japanese Culture), Tokyo, University of Tokyo Press, 1971, p. 167-169.

9

Watanabe Kazan, “Shinkiron” (A Private Proposal), in edited by Satō Shōsuke, Uete Michiari, Yamaguchi Muneyuki, Watanabe Kazan, Takano Chōei, Sakuma Shōzan, Yokoi Shōnan, Hashimoto Sanai, Nihonshisōtaikei 55 (Watanabe Kazan, Takano Chōei, Sakuma Shōzan, Yokoi Shōnan, Hashimoto Sanai, Japanese Thought System 55), Tokyo, Iwanami shoten, 1971[1838], p. 69.

10

Watanabe Kazan, “Gaikoku jijōsho” (On Matters Foreign), in edited by Satō Shōsuke, Uete Michiari, Yamaguchi Muneyuki, Watanabe Kazan, Takano Chōei, Sakuma Shōzan, Yokoi Shōnan, Hashimoto Sanai, Nihonshisōtaikei, p. 31.

11

Watanabe Kazan, Saikō seiyō jijōsho (On Matters Western - Revised), in edited by Satō Shōsuke, Uete Michiari, Yamaguchi Muneyuki, Watanabe Kazan, Takano Chōei, Sakuma Shōzan, Yokoi Shōnan, Hashimoto Sanai, Nihonshisōtaikei 55, p. 49.

12

I searched the Database of Chinese Classic Ancient Books, a database of over 10,000 Chinese book titles from the pre-Qín (778 –206 BC) to the Republican period (1912–1949), for cases of the compound appearing in print in China between 1750 and 1840. See Li Gāng, Jingkangzhuanxinlu 靖康傳信錄 (Accounts of Stories Transmitted in the Jingkang Era), Ginza, Yamashiroya Masakichi, 1865 (originally published in 1127).

13

Nakamura Kikuji, Kyōkasho no shakaishi: Meijiishin kara haisen made (Social History of Textbooks: From Meiji Restoration to the Defeat of War), Tokyo, Iwanami shoten, 1992, p. 2-3.

14

Ronald Dore, Education in the Edo Period, Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1965; Herbert Passin, Education and Japan’s Modernization, Teachers College, Columbia University, 1965. Quoted in Saitō Yasuo “Shikijinōryoku, shikijiritsuno rekisjitekisuii: Nihon no keiken” (Historical Shifts in Literacy and Literacy Rates—the Japanese Experience), Kokusaikyōryokuronshū, 2012, 15(1), p. 51-62.

15

Nakamura Kikuji, Kyōkasho monogatari: Kokka to kyōkasho to minshū (A Story on Textbooks: Nation, Textbook and People), Tokyo, Horupu shuppan, 1984, p. 65.

16

Katō Shūichi attributes this achievement to the then common practice of borrowing the corresponding translated terms already used in Chinese for the introduction of European and American words into Japanese. Katō Shūichi, “Meiji shoki no honyaku” (Translation during the early Meiji period), in Katō Shūichi, Maruyama Masao, Honyaku no shisō (Philosophy of Translation), Tokyo, Iwanami shoten, 1991, p. 342-380. See also Andre Haag, “Maruyama Masao and Katō Shūichi on Translation and Japanese Modernity”, Review of Japanese Culture and Society, 2008, 20, p. 15-46.

17

Unlike today’s system in which the number increases as students move through the grades, during the Meiji period the number started high and decreased. Calligraphy classes stopped at Upper Division Level 8 (10 years old). Ministry of Education, “Charter of Regulations for Elementary Education” (Addendum to the Ministry of Education Notification of November 10, 1872 [Meiji 5]) [online].

18

It served as a textbook for elementary school students through to middle school, as well as for adult education.

19

Masuno Keiko, “Mieru minzoku mienai minzoku: Yochishiryaku no sekaikan” (Visible race, invisible race, Cosmology of Yochishiryaku), in Kanagawa Daigaku 21 seiki COE program ed., Hanga to shashin: 19seiki kōhan dekigoto to image no sōshutsu (Woodblock Prints and Photographs: The Late 19th-Century - The Creation of Events and Images), 2006, p. 50-51.

20

These geography textbooks usually came in multiple versions, or had similar books with different titles. O. F. G. Sitwell, Four Centuries of Special Geography, Vancouver, University of British Columbia Press, 1993.

21

J. Goldsmith, W. Webster, A Grammar of Geography for the Use of Schools, with the Maps and Illustrations, London, William Tegg, 1868.

22

Tokyo Shoseki Co. Ltd. Company History Editorial Committee, Kyōkasho no hensen: Tokyo shoseki gojūnen no ayumi (Tokyo Shoseki – 50 Years of Progress), Tokyo, Tokyo shoseki kabushiki gaisha, 1959, p. 13.

23

Fukuzawa Yukichi, “Sekai kunizukushi” (Account of the Countries of the World), edited by Nakagawa Shinya, Fukuzawa Yukichi chosakushū dai 2 kan (The Complete Works of Fukuzawa Yukichi, Vol. 2), Tokyo, Keio gijuku daigaku shuppankai, 2002, p. 64.

24

Fukuzawa Yukichi, “Sekai kunizukushi” (Account of the Countries of the World), edited by Nakagawa Shinya, Fukuzawa Yukichi chosakushū dai 2 kan (The Complete Works of Fukuzawa Yukichi, Vol. 2), Tokyo, Keio gijuku daigaku shuppankai, 2002, p. 154.

25

Fukuzawa Yukichi, “Sekai kunizukushi” (Account of the Countries of the World), edited by Nakagawa Shinya, Fukuzawa Yukichi chosakushū dai 2 kan (The Complete Works of Fukuzawa Yukichi, Vol. 2), Tokyo, Keio gijuku daigaku shuppankai, 2002, p. 97.

26

Tokyo Shoseki Co. Ltd. Company History Editorial Committee, Kyōkasho no hensen:Tokyo shoseki gojūnen no ayumi (Tokyo Shoseki – 50 Years of Progress), Tokyo, Tokyo shoseki kabushiki gaisha, 1959, p. 13.

This is apparent in the following passage from the prefatory note, in “essential points” extracted from Western geography texts, “with no interpolation of my own point of view”. Fukuzawa, “Sekai kunizukushi”, prefatory note.

27

Eugène Cortambert, Chikyū sanbutsu zasshi (Global Products Compendium), translated by Horikawa Kensai, published by Izumiya Hanbei in 1872 (Meiji 5), p.1-3.

28

Akiyama Tsunetarō, trans, Hyakkazensho Jinshuhen (Encyclopedia, Volume on Race), Tokyo, Monbushō, 1874 (Meiji 7); William Chambers and Robert Chambers, Chambers’s Information for the People: New and Improved Edition, Philadelphia, J.B. Lippincott & Co., 1867.

29

Uchida Yoshikazu, Chigaku shinpen (Geography New Edition), Tokyo, Kinkōdōshoseki, 1877 (Meiji 10).

30

Miccheru, Bankoku chishi kaitei (World Geography Guidebook), Tokyo, Ejima Ihei, 1878 (Meiji 11).

31

Yamada Yukimoto, Shinsen chiri shōshi kan-ni (Newly Compiled Geography Pamphlet, vol.2), Tokyo, Kōfūkan, 1879 (Meiji 12).

32

Shihan gakkō, Bankoku chishiryaku, Shukan, Chiri sōron (Abridged World Geography Volume 1 – Introduction to Geography), Tokyo, Ministry of Education, 1874 (Meiji 7).

33

Uchida Yoshikazu, Chigaku shinpen (Geography New Edition), Tokyo, Kinkōdōshoseki, 1877 (Meiji 10), p. 28.

34

HATA Masajirō, Chūtōkyōiku bankokuchishi (Middle School Education World Geography), Tokyo, Hakubunkan, 1891 (Meiji 24).

35

Yamada Yukimoto, Shinsen chiri shōshi kan-ni (Newly Compiled Geography Pamphlet, vol. 2), Tokyo, Kōfūkan, 1879 (Meiji 12).

36

Yamada Yukimoto, Shinsen chiri shōshi kan-ni (Newly Compiled Geography Pamphlet, vol.2), Tokyo, Kōfūkan, 1879 (Meiji 12), p. 29.

Historians have shown that this discourse was one of the “invented traditions” of the Meiji period.

37

Ritter Harper and Humbolt Harper, Harper's School Geography with Maps and Illustrations, New York, Harper & Brothers, 1886. This mention in Bankoku chirishi implies that an edition of Harper’s School Geography was published before 1877, but I am as yet unable to confirm this.

38

Ritter Harper et Humbolt Harper, Harper's School Geography with Maps and Illustrations, New York, Harper & Brothers, 1886, p. 18.

39

Ritter Harper et Humbolt Harper, Harper's School Geography with Maps and Illustrations, New York, Harper & Brothers, 1886, p. 19.

40

Noguchi Yasuoki, Chūgaku bankokuchishi jōkan (Middle School World Geography, Volume 1), Tokyo, Seibidō, 1896 (Meiji 29), p. 2-3.

41

Yazu Masanaga, Nihonteikoku seijichiri (Political Geography of the Japanese Empire), Tokyo, Maruzenshōsha, 1893 (Meiji 26), p. 47.

42

Jonsuton Keisu, Chūtōkyōiku Joshi chirikyōkasho dai-i-chitsu (Mid-Level education Johnston’s geography textbook, first part), Tokyo: Uchida rokakuho publishing co., 1888-1890. contains the following explanatory note: “The Aryans” “came from central Asia and spread among the ethnicities in all directions” (p.150); the “Aryan Race [jinshu]” also appears in Noguchi Yasuoki, Chūgaku bankokuchishi jōkan, Tokyo, Seibidō, 1896 (Meiji 29).

44

HATA Masajirō, Chūtō kyōiku (Middle School Education World Geography), Tokyo, Hakubunkan, 1891 (Meiji 24), p. 20.

45

Kinkōdōshosekigaishahenshūjo ed., Shōgaku bankoku chishi shukan (Elementary School World Geography vol. 1), Tokyo, Kinkōdō, 1894 (Meiji 27), p. 37-38; Miyake Yonekichi, Chūgaku gaikoku chisi zen (Middle School Foreign Geography Complete), Tokyo, Kinkōdō, 1896 (Meiji 29), p. 27-28.

46

Takashiro Yogorō ed., Bankoku shinchishi kannojō (New World Geography, vol.1), Tokyo, Shishodō,1894 (Meiji 27), p. 47.

47

Yamada Yukimoto ed., Shin chishi (New Geography), Uehara Saiichirō, 1893 (Meiji 26), p. 8.

48

In addition to the above, other works contain descriptions related to “race” [jinshu]. These include Nakamura Goroku ed, Chūtō chiri bankokushi (Mid-Level Geography of the World), Meiji 25; Matsushima Takeshi, Kinsei shōchirigaku gaikoku no bu (Modern Elementary Geography: Foreign Countries), 1895 (Meiji 28); Miyake Yonekichi, Chūgaku gaikoku chisi zen (Middle School Foreign Geography Complete), Tokyo, Kinkōdō, 1896 (Meiji 29); Noguchi Yasuoki, Chūgaku bankokuchishi jōkan (Middle School World Geography, Volume 1), Tokyo, Seibidō, 1896 (Meiji 29). Some of these also employ the term shu in addition to jinshu.

49

Shōgaku bankoku chishi shukan (Elementary School World Geography, Volume 1), Meiji 27, p. 39.

50

Kōtō shōgaku bankoku chiri (Higher Elementary School World Geography), Meiji 26, p. 64.

51

Shibue Tamotsu, Kōtō shōgaku bankoku chiri (Higher Elementary School World Geography), Tokyo, Hakubunkan, 1893 (Meiji 26), p. 61.

52

Yun Koncha, Minzoku gensō no satetsu (The Failure of the Illusion of Ethnicity), Tokyo, Iwanami shoten, 1994.

53

“Meiji Education” National Archives [online].

54

Yokoyama Matajirō, Chūtō chibungaku (Mid-Level Physical Geography), Tokyo, Hōeikan, 1900 (Meiji 33).

55

See also: Matsushima Takeshi, Kinsei shōchirigaku gaikoku no bu (Modern Elementary Geography: Foreign Countries), Tokyo, 1895 (Meiji 28); Ono Masayoshi and Muraki Kangō, Chūtō shinchiri gaikoku no bu (Mid-level School Geography of Foreign Countries), Tokyo, Rokumeikan, 1901 (Meiji 34), p. 287.

56

Nakamura Goroku ed., Chūtō chiri chirigaku (Mid-Level Geography, Geography), Tokyo, Bungakusha 1891 (Meiji 24), p. 53-54.

57

Yamanoue Manjirō, Saikin tōgōgaikokuchiri chūgakuyō jō (Recent Integrated Foreign Geography for Middle Schools), Tokyo, Dainippon tosho kabushikigaisha, 1906 (Meiji 39), p. 11.

58

Satō Denzō ed., Chūgaku honpō chiri kyōkasho (Middle School Textbook of Japanese Geography), Tokyo, Rokumeikan, 1901 (Meiji 34), p. 26.

59

Satō Denzō ed., Chūgaku honpō chiri kyōkasho (Middle School Textbook of Japanese Geography), Tokyo, Rokumeikan, 1901 (Meiji 34), p. 26-27.

60

Satō Denzō ed., Chūgaku honpō chiri kyōkasho (Middle School Textbook of Japanese Geography), Tokyo, Rokumeikan, 1901 (Meiji 34), p. 27.

61

Satō Denzō ed., Chūgaku honpō chiri kyōkasho (Middle School Textbook of Japanese Geography), Tokyo, Rokumeikan, 1901 (Meiji 34), p. 28.

62

The textbook Mid-Level Geography and Geographical Studies, Volume on Japan (Meiji 33) also touches on the Ainu, Taiwanese, and Ryūkyū Islanders along with the Yamato Race. The text reflects the zeitgeist of the Meiji period by arguing for the superiority of the Yamato people while in the same breath mentioning reverence for the imperial family. Bungausha ed., Chūtō shōchiri honpō no bu (Mid-Level Geography and Geographical Studies, Volume on Japan), Tokyo, Bungakusha, 1900 (Meiji 33), p. 17-18.

63

Yamazaki Naokata, Chirigaku tsūron (General Education Geography Textbook: An Introduction to Geography), Tokyo, Kaiseikan, 1903 (Meiji 36).

64

In addition to the above, the following texts published in the Meiji 30s also contain passages regarding race (jinshu): Yamazaki, Chirigaku tsūron; Wakimizu Tetsugorō, Chiri kyōkasho: Gaikoku (Geography Textbook: Foreign Countries), Tokyo, Kinkōdōshoseki, 1904 (Meiji 37); Gaikoku shinchiri (New Foreign Geography), Tokyo, Sanseidō, 1905 (Meiji 38).

65

Ministry of Education, Kōtō Shōgaku chiri Kan-ni (Higher Elementary School Geography Vol. 2) Tokyo, Nihonshoseki, 1912, p. 48

66

Yamamuro, Shin'ichi, Shisō kadai toshiteno Ajia (Asia as a Subject of Intellectual Thought), Tokyo, Iwanami shoten, 2001, p. 50-53.

67

Yamazaki Naokata, Chirigaku tsūron (General Education Geography Textbook: An Introduction to Geography), Tokyo, Kaiseikan, 1903 (Meiji 36).

68

Yazu Masanaga and Akaboshi Yoshito, Kōtō chiri Yōroppashū no bu (Upper Level Geography – Europe), Tokyo, Maruzenshōsha, 1910 (Meiji 43), p. 17.

69

Taking the example of Theory of Social Studies Education, a mere 17 pages were devoted to foreign geography in the Meiji 44 edition, but this had increased to 43 pages in the Taisho 8 edition, and ballooned to 82 pages by the Taisho 15 edition. Educational Science Research Society/Social Studies Section, Shakaika kyōiku no riron (Theory of Social Studies Education), Tokyo, Mugi shobō, 1966, p. 60.

70

Wang Ping, “Nihonjin no Chūgokukan no rekishiteki hensen ni tsuite” (On the Historical Changes of the Japanese “China Perception”), Hiroshima Daigaku Management Kenkyū, 2004, 4, p. 264.