The concept of field allows scholars to delimit individuals’ actions at the meso-level (halfway between macro and micro approaches), in differentiated social spheres who have their own rules of the game and particular interests. Carefully developed by Pierre Bourdieu starting in the 1960s in order to reflect upon the process of social differentiation of spheres of activity that occur with the division of labor, all the while applying a relational and topographical approach, the concept of field served as a research program (as defined by the philosopher of science Imre Lakatos) and generated a substantial amount of research on political, economic, religious, academic, legal, philosophical, literary, artistic, intellectual, editorial, and athletic fields, among others. In the United States, different uses of the concept of field have emerged, at first in the 1980s with the idea of “organizational fields” created by Paul DiMaggio and Walter Powell as part of a neo-institutional approach, and later on in the 2000s with the notion of “strategic action fields” proposed by Neil Fligstein and Doug McAdam in order to connect this neo-institutional approach with theories of collective action.

The Origins and Genesis of Field Theory in Sociology

The concept of field is borrowed from theoretical physics: it understands the relations between elements in a given space, conceived of as a force field, according to the laws of attraction and repulsion. It was transposed in psychology by Gestalt theorists, notably Wolfgang Köhler, who emphasized the interdependency of elements in a perceptional experience and developed a topographical approach1Kurt Lewin adapted it to social psychology to think through the interactions between an individual and his or her environment. It is this same understanding of field that Bourdieu introduces into sociology, where this abstract concept allows for the methodological autonomization of a space of activity, providing that the historical conditions of its autonomization are studied, as he indicates for the fields of cultural production. The use of the concept of field responds to a problem which is twofold2.

Firstly, how should one think about the historical process of the differentiation of social activities, which takes place alongside the division of labor without falling into a functionalist approach? This double process is neither inevitable nor automatic. The autonomization of a domain of activity generally results from the struggle led by a group of specialists (for example, legal practitioners) to obtain social recognition of their authority and expertise in a given domain, instituting a division between professionals and laypersons (between the clergy and non-believers, for example). Field theory systematizes the analysis of this process identified by Max Weber and draws methodological consequences from it, namely the possibility of autonomizing a field as an object of study.

However, and this constitutes the second problem, this autonomy always remains relative. Bourdieu borrows the concept of autonomy from different Marxist approaches, where it had been introduced into the context of the debate surrounding “reflection theory”, which regarded works as superstructures that reflect underlying social conditions. Complicating this theory, certain Marxist theorists have suggested that literary and artistic works were mediated by a worldview that was not a simple reflection of the artist’s or his or her audience’s class belonging, but could echo the contradictions that shape the conditions of production. Bourdieu, however, finds fault with these thinkers for not taking into account the mediation exerted by the fields of cultural production regarding economic and social conditions: it is here: in what he calls the “field effect”, where he situates that relative autonomy of this universe.

Pierre Bourdieu, portrait.

Indeed, works bear the marks of their conditions of production since the cultural producers are engaged in a competitive struggle that obeys certain rules and specific interests, including but not limited to economic, political and social ones. Pertaining to the social space, “the field effect” produces a “refraction” effect (another concept that Bourdieu borrows from physics): it retranslates the exterior constraints following its own logic. This logic stems from the structure and history of the field. Such an approach (just as valid for cultural productions as for science, philosophy or law) allows to avoid a purely internalist approach as well as all forms of sociological reductionism.

The structure of the field is defined according to the (unequal) distribution of specific capital within it: agents endowed with specific capital hold dominant positions, those who have less hold dominated positions. Breaking with substantialism (relying particularly on Ernst Cassirer’s book Substance and Function3) and interactionism (the symbolic interactionism and spontaneous interactionism that prevails in literary and art history, where the tendency to differentiate trajectories foment interest in interpersonal relationships), this topographical approach claims to be structural (relational) and objectivist: united by the competition over the same issues at stake, the acquisition of specific capital, the agents are defined objectively in comparison to one another independently of the interactions that take place between them. Interactions that objectivist analysis allows, furthermore, to explain through shared dispositions, the types of capital (cultural, economic, social, political) held and the positions occupied in the field and in the social space: thus, a purely descriptive network analysis takes on its full meaning in light of the objective properties of individuals’ properties.

Although his field theory, like his understanding of the social space, is indebted to the structuralist method that he uses not only to analyze a group’s world view but also the social relations themselves, Bourdieu retains a dynamic understanding of these relations from Marxism, relations that results from their agnostic dimension. The competitive struggle is indeed the expression of principles of opposition which structure the field and determine the antagonisms and alliances (following the laws of attraction and repulsion)4. These principles of opposition also create the structural homology between fields.

In each field the “dominated” are opposed to the “dominant ones”, the latter being inclined towards preserving the dominant definition of the activity in question (“orthodoxy”), while the “dominated” are better positioned to contest it (“heterodoxy”). Drawing from Max Weber’s sociology of religions5, Bourdieu systematizes the opposition between priest and prophet, to whom he confers a paradigmatic character, transposing it to the fields of artistic production where it crops up in the opposition between consecrated producers and the avant-garde (for example, the members of the Academie française vs. the Surrealists)6. A second structuring distinction opposes the proponents of field autonomy, based on the judgment of peers articulated following particular criteria for determination of the symbolic value of products, against those who tend to import heteronomous, ideological or economic constraints into the field.

These positions evolve depending on various factors, exogenous, like the situations of crisis or politicization, or endogenous, namely internal struggles and aging populations. If the exogenous factors contribute to the synchronization of fields (like in May 19687), the endogenous factors impose a temporality specific to each field, another sign of their relative autonomy. Moreover, the relatively autonomous fields are characterized by their autotelism or self-referentiality, i.e. references to their own history: this is the case for the fields of cultural production (literature, art, music), as well as the scientific and legal fields, where past problems and their solutions cannot be ignored without the risk of being excluded from the field.

Thus, the field is a space of possibilities in which position taking – namely, the choices between different options more or less constituted as such – is defined by significant differences (according to the model of structural linguistics), differences that make sense with respect to the history of the field (for example, between tonal and atonal music, or between analytical and “continental” philosophy). For this reason, the subject matter of the work is neither the individual nor the class as Lucien Goldman suggests but, according to Bourdieu, the field on the whole.

In this way, the notion of the space of possibilities is similar to the Foucauldian concept of “the strategic field of possibilities”, however, it is distinct, especially given Bourdieu’s very specific use of the concept of “strategy” in order to understand the agents’ distinct forms of investment8. Far from supposing rational and reflexive, even cynical action, the concept of strategy refers, both in Bourdieu’s theory of practice, to agents’ room for improvisation in relation to the exterior constraints they face, and to their dispositions. In field theory, he articulates the concept of illusio, which justifies an individual’s feel for the game (sens du jeu), their belief in the relevant activity, and points to the specific profits, more often symbolic than economic, in a given field. The concept of strategy indeed aims to describe the confrontation between a social trajectory and a space of possibilities. This trajectory is largely determined by individuals’ habitus, in other words by the social structures that they internalize during their socialization in the form of dispositions and that in turn structure their schemes of perception, action, and evaluation (taste). The question of the relationship between individuals’ social properties and their position taking within the field is therefore not a given, but rather a central object in the study of how a field functions.

Towards a general theory of fields

Beginning in the 1970s, Bourdieu developed the project of a general theory of fields, which was never published in his lifetime but, of which he left traces, from the seminars and conferences that he dedicated to this question9, to the research that he, members of his team, and his students undertook on specific fields: literary, religious, scientific, political, legal, academic, philosophical, artistic, economic, editorial, not to mention on the field of haute couture. Since it is impossible to inventory all of the scholarship that has used this concept, I will limit myself here to on the one hand the contribution of field theory to the study of different sectors of activity, and on the other, the contribution of these fieldworks to the general theory.

The reflection on the fields of cultural production, which dates back to the beginning of the 1960s10, aims to create a “science of creative works” that transcends the alternative between internal analysis, which at the time was personified in literary studies by New Criticism and especially structuralism, and external analysis, split between the singularizing biographical approach (Sartre’s The Family Idiot being the most masterful example of this) and the reductionism of Marxist theory. Contrary to the myth of the “uncreated creator” invented by romantic ideology, field theory reminds us that cultural producers do not escape social determinisms and that they do not create in isolation. Contrary to the notion of “reflection”, field theory emphasizes that these determinisms are mediated, refracted by the field, specifically by a pre-existing space of possibilities, that it is necessary to reconstruct in order to explain the principles behind their esthetic choices.

Graph, In Pierre Bourdieu, “Le marché des biens symboliques”, L'Année sociologique, n° 22, 1971, p. 114.

These considerations raise two historical questions. The first relates to the process by which these fields gained autonomy, which, according to Bourdieu, depends on three conditions: the emergence of a group of producers who specialize in the activity in question (literature, painting, music, sport); the existence of specific authorities with the power to consecrate; the creation of a market of symbolic goods, which upsets the order of supply and demand with respect to the patronage that prevailed during the Ancien Régime and that was based on commissions11. Such a market emerged as early as the end of the 18th Century, but the process of autonomization took place neither at the same time, nor in the same way in literature and in painting: while the rise of publishing and the liberalization of print at the beginning of the 19th Century abandoned writers to the ruthless law of the book market, the art market remained highly regulated up until the middle of the century by a single authority, the Académie des Beaux-Arts, which concentrates the monopoly of the power to consecrate through the control of the access to the Salon12. However, the multiplication of producers (correlative to the increase in schooling) and the bohemian lifestyle adopted by those who were excluded from the academic system contributed to the emergence of a market on the margins of this system, centered around artist societies that operated like retailers’ cooperatives.

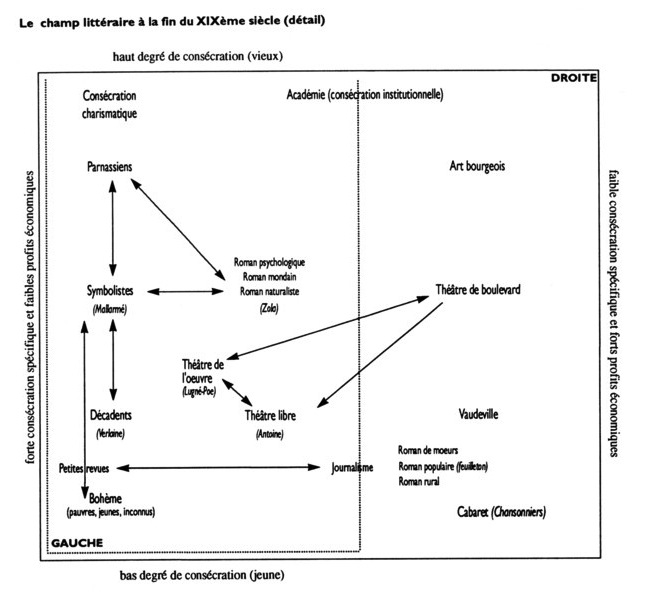

While the artistic field forms in opposition to the State, guardian of the academic system, the autonomy of the literary field must be asserted in relation to the market, which has from the outset challenged the Académie française’s power of consecration. As described by Bourdieu in The Rules of Art, against the circuit of large-scale production, forms a pole of small-scale production, ruled by the logic of the market, that imposes the primacy of the symbolic value of creative works, established on the basis of peers’ specific judgement criteria at the middle of the 19th Century.

Pierre Bourdieu, “La production de la croyance. Contribution à une économie des biens symboliques”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, vol. 13, 1977, graphique p. 24.

The economy of symbolic goods is an “reversed” economy, in which short term profitability is at odds with the process of the consecration of works over the long-term. A process which is likely to lead to the “canonization” of certain authors or artists, by integrating their works, made “classics”, into a national and universal cultural heritage, through the intervention of the educational system in particular13. The authorities, especially publishers, play a major role in this process of value production, economic value at the pole of large-scale production, symbolic value at the pole of small-scale production14.

In France, this reversal took place during the Second Empire by the advocates of “art for art’s sake”, which was just as opposed to “social art”, which is to say politically committed art, as it was to the Ecole du bon sens, which grouped together authors from the high society pole of the literary field, close to the dominant fractions of the dominant class15. Bourdieu analyzes the condition of this quest for autonomy through the double rupture carried out in particular by Flaubert and Baudelaire. He considers the latter as a “nomothète” since he instituted a new nomos in the literary field, characterized by its independence with regard to external powers, be they economic or political, and by anomie turned law. By freeing themselves from bourgeois demands in order to affirm the primacy of pure aesthetics, which goes hand in hand with an ethos combining rigor at work and anticonformism, Flaubert and Baudelaire bring about a “symbolic revolution” that will have lasting consequences on the literary field.

Pierre Bourdieu, “Le champ littéraire”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, vol. 89, 1991, p. 3-46, graph page p. 31.

How do “symbolic revolutions” like this one occur? This is the second historical question raised by the study of the fields of artistic production, which is also germane to the scientific field or even the field of haute couture16. While this question emerges from the outset of Bourdieu’s research work on cultural universes, the most fully developed formulation can be found in his lectures at the Collège de France on Manet. The difficulty in understanding these symbolic revolutions, Bourdieu explains, stems from the fact that our own categories of aesthetic perception are the products of these revolutions. One must therefore reconstruct the worldview predating this revolution, just as Bourdieu does in these lectures, by highlighting the driving principles behind the academic aesthetic.

Manet eventually goes on to destroy this aesthetic code, which was backed by a state monopoly. Neglecting technical mastery (perspective, relief, chiaroscuro) and the ‘finish’, which were of great importance to his professors, he works the canvas in its bidimensionality, thus transgressing the laws of perspective and relief - and dignifies sketches (which the Académie’s masters considered nothing more than a minor step prior to “invention”, the process of finishing). Moreover, he calls into question the hierarchy of subject matters, which was indexed to objects’ place in the social hierarchy, and favors references to the history of art rather than merely to history – which leads him, if not to devoid the work of any and all meaning, than at least to render it ambiguous, thus breaking with the principle of legibility (or the “message”), to the extent of eliciting puzzlement and contradictory interpretations, if not mocking laughs or outraged scolding.

Manet, portrait.

Bringing to light the transformations of the conditions of production, as at once technical (the invention of tubes of paint makes painting en plein air possible) as morphological (the growth of the population of artists) and economic (the development of a parallel market to the academic system) makes it possible to break with an idealistic and individualizing history, but is not enough to explain symbolic revolutions. Sociological analysis must also take into account the agents’ dispositions – here we discuss Manet’s: the significant economic, cultural and social resources possessed by this son of a trial court judge descended from a family of magistrates, his training within the academic system, his great pictorial culture, the freedom that his private income affords him, and his tightly knit network of relations, salons on the one hand, cafés and the bohemian milieu on the other. This extraordinary concentration of assets, associated with what Bourdieu calls a “habitus clivé”, or “cleft habitus”, split between the two poles of the field of power (economic and cultural), predisposed Manet to achieve this revolution. A revolution that, like all “symbolic revolutions” is defined not by destruction but through the integration of that which preceded it: the rupture takes place in continuity, as shown by the practice of pastiche. Thus, even in these universes where, unlike the bureaucratic world, the positions are left to be created, the most innovative practices fit into a dialectical relationship with the space of possibilities.

The field of haute couture offers an equally rich ground for observing the logic of fields: the production of belief in brand fetishes, by means of a process that Bourdieu compares to the workings of magic analyzed by Mauss; structural opposition between the “right bank” (Balmain) and the “left bank” (Scherer); and symbolic revolution accomplished by Courrèges who, synchronizing an internal revolution with social transformations, replaced the discourse on fashion with a reflection on the lifestyle of the modern woman, who was supposed to feel comfortable, free, and relaxed17.

Dressed by Balmain, 1954 ; Dressed by Scherer, 1983 ; Dressed by Courrèges, 1968.

This model of analysis also serves for thinking about a relatively autonomous field’s conditions of existence, where judgement from peers overrules heteronomous logics (ideological or economic), as well as scientific revolutions18. The scientific field differentiates itself from the fields of cultural production because its public is primarily made up of peers, which exacerbates the logic of regulated competition for the accumulation of specific capital. This defining characteristic allows Bourdieu to reject relativism for a historicist rationalism founded on field theory. Indeed, the introduction of social, political, and economic interests into the analysis of the conditions of production of scientific knowledge leads to a relativism ushered in by Thomas Kuhn’s model for thinking about scientific revolutions (although he did not subscribe to it himself). The sociology of sciences dramatically changed from deploying a rationalism founded upon the professional norms that dictate scholarly ethos (universalism, communalism, disinterest, skepticism) according to Robert Merton’s functionalist model, to using the relativism of the sociology of interests and constructivist approaches. Even though Bourdieu breaks with the peaceable vision of a scientific community working in harmonious cooperation in the universal interest of science, the concept of field allows him, while reintroducing power relations and non-scientific interests that span these universes, to simultaneously ensure that the field’s relative autonomy and the rules it imposes guarantees the universal validity of scientific knowledge. The scientific field produces an “interest in disinterest” which, associated with the collective control of peers, is one of the conditions of its autonomy, albeit a sometimes relative one. The analysis of the workings of the scientific field has, moreover, an additional value, in as much as it contributes to scholarly reflexivity.

The “field effect” is particularly perceptible in the philosophical field, which achieved a high degree of conceptualization and where the mastery of past references is the sine qua non of access to recognition from peers. The analysis of Martin Heidegger’s political ontology, placed in the context of the field of ideological production of his time, reveals not only the conservative ethical-political, nay reactionary framework, that the philosopher, like most of the mandarins whose position in the field of power was in decline, shared with “völkisch” humor – and which is the source of his embrace of Nazism -, but also the transubstantiation that the work of philosophical formatting subjects them to, euphemizing to the point of rendering them unrecognizable. The field’s specific censorship is therefore at the root of this “philosophical sublimation” transaction. The field effect gives “an objective foundation to the illusion of absolute autonomy” (1988: 10). This approach to fields thus makes it possible to transcend the alternative between an ideological reading of the work and a purely philosophical reading, an alternative which Heidegger’s students till this day continue to dispute19.

In addition to his work on Heidegger, Bourdieu’s research program on the scientific field, which is based on existing works in the history of science, was developed in the context of an empirical survey on the academic field20. Taking French academics and researchers in the 1960s as the object of study, the research program is based on a prosopographical survey that combines social properties of individuals and indicators of the positions they hold in the field. These indicators are elaborated by distinguishing different forms of capital, in the temporal (heteronomous) and symbolic (autonomous) order: academic power, scientific power, scientific prestige and intellectual notoriety capital. The institutions – universities, research institutions, the Collège de France - are conceived both as variables (belonging to such-and-such institution as an indicator of the position held by the individuals) and as agents in their own right within the field.

Pierre Bourdieu, Homo academicus, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1984.

The prosopographical data was exploited using Multiple Correspondance Analysis, the preferred statistical method for understanding the principles structuring a field. The academic field appears to be structured by the opposition between a temporally dominant pole, occupied by the law and medical schools, and a temporally dominated pole, where science departments are located – the humanities and social sciences are found between these two poles. This intermediary position is in fact a privileged site of observation of the struggles between two forms of academic power, temporal and symbolic. Colleges of arts and humanities are indeed divided between a pole of academics oriented towards the reproduction of the group (“corps”), thus towards the exercise of temporal power in the cultural order, and a pole of agents more oriented towards research, most often belonging to prestigious, yet marginal authorities like the Collège de France, and who are more often producers than reproducers (and who are also more internationally oriented). The study thus allowed for the differentiation of two types of consecration, temporal and symbolic, which each have their equivalents in the fields of cultural production with on the one hand, public success and institutional recognition (prizes, academies), and on the other, recognition by peers and specialized critics (criticism being a field structured by homologous oppositions).

The degree of centralization of the field varies depending on the ability of an institution to monopolize the power of reproduction within it, for example the Catholic Church, the University, or the Beaux-Arts system. When an institution attains a high degree of monopoly in a field, we can speak of a “corps” – as in the Corporatio of medieval canonists – rather than “field”21. The closing off of recruitment through competitive exams, the establishment of numerus clausus, etc. are ways of controlling access to the field, which are likely to lead to its transformation into a corps through the homogenization of social recruitment and the inclusion of an ‘esprit de corps’. However, it is rare that a field’s social recruitment is that homogenous, and the differences in status (or in corps in the administrative field) often produce principles of structural opposition, such as between the members of the Academy of Beaux-Arts and bohemian painters, or between legal theorists and legal practitioners (according to an opposition that Bourdieu borrows from Weber).

Pierre Bourdieu, Homo academicus, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1984.

One of the advantages of field theory in comparison to the sociology of professions is that it always considers activities, even when they have achieved a certain amount of autonomy, as relatively heteronomous (by analyzing the way in which class relations are refracted through habitus) and as more or less heterogeneous. This heterogeneity may result from work conditions and statuses (for example, the statuses of self-employed, salaried employee, or civil servant which coexist sometimes in one sector of activity) or social recruitment (whether it is social origins or educational training, pitting for example alumni of Oxbridge or French grandes écoles against students enrolled in universities). Concealed by professional ideology, such divisions often are often inherent in the power relations that structure the fields and the internal struggles that are behind their transformations. The legal field during the Ancien Régime differentiated itself in this way into three groups: government lawyers, who made up the bureaucratic pole, the judicial officers, who claimed a certain amount of autonomy with respect to royal authority, and the low ranking judicial clergy, who, during the French Revolution, managed to invert the hierarchy of the power relations with the Nobles of the Robe (to which both the judicial officers and government lawyers belonged to), and to impose the conception of the Nation state22.

Another attribute, resulting from the process of field autonomization is the divide between specialists and laymen which excludes the latter from field activities by delegitimizing their judgement. This dispossession of laymen, rooted in the religious model distinguishing clergy from non-clergy, can be observed in many professional universes (law, medicine, architecture, science, sport) and above all in the political field. In his studies on the political field, Bourdieu analyzed in particular the phenomenon of the representation and the transfer that it implies, a phenomenon that is at the heart of the monopolization of politics by professionals23.

The political field is, along with the economic field, a dominant field within the field of power. The latter is structured by the opposition between those who possess economic and political capital and those who are more endowed with cultural capital24. Owing to the help of neoliberal ideology, the economic field tends to subordinate the other fields more and more, notably the political field (through the intermediary of New Public Management), the journalistic field25, and the fields of cultural production (through the logics of concentration and the merger and acquisition of cultural industries, whose effects on French publishing in the 1990s were studied by Bourdieu26), by imposing on them its logic of financial profitability. Such a dependence threatens the autonomy of these fields by reinforcing the heteronomous pole against the autonomous pole, and raises the question of relations between fields.

Pierre Bourdieu, Le Champ journalistique et la télévision, May 1996.

Uses of the concept of field and methodological questions

Having inspired numerous empirical studies, the concept of field raises methodological and theoretical questions which we will give an overview of here. A lot of this research has focused on the literary field27, but important work has been done on other universes – political, legal, intellectual, journalistic, academic, artistic, and cinematographic fields, as well as on disciplinary fields such as philosophy, economy, sociology. And while most of these studies concentrate on French cases, there are a few remarkable works on other countries, such as Sergio Miceli’s pioneering research on the conditions of the emergence of an intellectual field in Brazil28.

The analysis of a field necessitates three operations, the study of specific authorities, the distribution of the social properties of individuals according to the positions occupied in the field, the reconstruction of the space of possibilities (and the space of actual position taking). A series of prosopographical surveys focused on the French literary field. One such study produced by Rémy Ponton took into account 616 writers active during the second half of the 19th Century, and revealed the disparity that exists, as far as social properties are concerned, between writers aligning themselves with different literary movements, like the psychological novelists and naturalists (the latter being less endowed than their predecessors)29. Anne-Marie Thiesse conducted a study on regionalist writers from the beginning of the 20th Century, relegated, in a centralized country like France, to the margins of the literary field30. For her own research on the French literary field during the Occupation, Gisèle Sapiro studied the major literary authorities and built a prosopography of 185 French writers active during this period, which she interpreted using a Multiple correspondence analysis31.

Other studies have focused on a central figure, modeled on Bourdieu’s analyses of Flaubert and Baudelaire. Anna Boschetti reconstructed Sartre’s trajectory and showed that he overcame, after the war, the former separation between the literary field and the academic field; she also developed indicators of the dominant position of his periodical, Les Temps modernes, in the field of intellectual journals (such as the citations between journals and the cultural capital held by the members of the editorial board)32. Poetry, where the formal dimension is more important and the rules of composition are more restrictive, is a privileged site to observe symbolic revolutions: Anna Boschetti studied the one carried out by Apollinaire by reconstructing the space of possibilities during his era33, whereas Pascal Durand analyzed the one carried out by the young Mallarmé who applied a radical treatment to the material that he borrows from post-romanticism34. Pascale Casanova sees in Samuel Beckett’s refusal of representation a transposition of the work of abstraction performed at the same time in painting, which raises the question of loans from one field to another35. The avant-garde also constitutes a fertile site of investigation for examining the logics of subversion at work in the fields of cultural production36. Research has also been conducted on the German literary field at different periods37.

Like the literary field, the academic field was the subject of a substantial amount of scholarship. Connecting the processes of professionalization and specialization with the creation of a field, Jean-Louis Fabiani studied the training of a “corps” of philosophy professors during France’s Third Republic, a group whose mental structures and categories of classification he grasps through a close look at the syllabi, and the simultaneous emergence of a market for philosophical books, distinct from literary production38. Christophe Charle’s comparison of the social recruitment of the literary and academic fields at the beginning of the 20th Century shows that writers are overall better endowed than Parisian university professors, who are themselves at the height of their academic careers39. In his study on the founding principles of economic belief, Frédéric Lebaron, for his part, revealed with a Multiple Correspondence Analysis, the opposition between “pure” economists (neoclassical and regulationist) endowed with a great deal of scientific capital and those who have temporal resources because of ‘political’ positions that they hold as consultants, political forecasters or within firms40.

Norbert Bandier, Sociologie du surréalisme. 1924-1929, Paris, La Dispute, 1999; Pascale Casanova, Beckett l'abstracteur. Anatomie d'une révolution littéraire, Paris, Le Seuil, 1997; Pascal Durand, Mallarmé. Du sens des formes au sens des formalités, Paris, Le Seuil, 2008.

Bourdieu’s discussion of the problem of political representation opened up a set of questions about on the one hand, the social properties of politicians, their variations in time and space41, and on the other, individuals participating in political labor: advisors, activists, pollsters, or communication experts, whose growing importance is maintained by the increasing dependency of the political field towards the field of media. Furthermore, the conception of the State as a meta-field opens up perspectives for renewing the study of public policy42.

A number of studies have raised questions about the relationships between fields: relations of subordination (thus, intellectual production does not start to become autonomized from the religious field till the 18th Century), of dependence, of hierarchy (between disciplines within the academic field for example) or of exchange (between the literary and artistic fields). Studies on the politicization of the intellectual field in moments of crisis that lead to the loss of autonomy, whether it is the Dreyfus Affair or the French literary field during the German occupation43, reveal that political position taking is tightly linked to the positions held by agents in their field of reference. These studies confirm the effect of refraction exerted by the field on exterior constraints, while highlighting the heteronomous role played by certain authorities at the edge of the field of power, like the Académie française.

This structural homology between positions and political position taking is also apparent in the differentiated forms of politicization at the different poles of the literary or intellectual fields, according to dominant or dominated positions, the degree of autonomy, and in the intellectual field, the degree of specialization44. Heteronomous logics resulting from the subordination to religious and political fields were also treated in the case of catholic and communist intellectuals, the latter bringing into play the condition of political “obedience”45. The relationship between the journalistic and the economic fields has been explored via the field of the financial press46.

The essential historicity of fields raises the question of their genesis and their temporality. In his seminal book Naissance de l’écrivain, Alain Viala traces the beginning of the process of autonomization of the literary field back to the 17th Century, with the emergence of rankings of men of letters, claims for royalty payments, and the official recognition of the Académie française, who is bestowed the authority to codify rules regarding language and literature47. This is why Viala disputes along with Denis Saint-Jacques, the chronology proposed by Bourdieu in The Rules of Art48. For his part, Christian Jouhaud draws attention to a paradox: the autonomization of the literary field is achieved through a reinforced dependency on the State, epitomized by the officialization of the Académie française49. It can be said that this also applies to the artistic field, which the State promoted to the rank of liberal art with the creation of the Académie des Beaux-Arts. Nevertheless, in the two cases if there exists a consecrating authority and more or less specialized producers, the third factor of field autonomization is missing, namely the existence of a market allowing to evade State control.

The fields of cultural production are thus located between the State and the market, which more or less exerts pressure on them, depending on the political regime and economic conditions. If the market allowed for their autonomization from the State, the State can in return protect them from economic constraints with laws (such as the French fixed book price law) or financial policies supporting the arts and cultural production50. Studies on communist regimes, where the power to consecrate was monopolized by an authority controlled by the Communist party, the Writers’ Union, show however, that forms of relative autonomy can subsist even in contexts of increased heteronomy and dependency on the State51. Likewise, autonomous logics can be observed even in the fields of cultural production most dependent on the market such as film, which is also structured according to the opposition between the pole of large-scale production and the pole of small-scale production52, the latter receiving a great deal of financial support in France by the State (as is the case at the pole of small-scale production in the field of publishing). If Bourdieu analyzed the process of the autonomization of a pole of small-scale production as concerns the market, literary trials offer a fertile site for observing other kinds of heteronomous logics, political and moral, that continue to bear upon literature, the social expectations which it is the subject of, as well as the progressive process of State recognition of its autonomy beginning in the 20th Century53. In addition, the autonomization of the literary field must be explained in the context of the division of intellectual labor that increased throughout the 19th Century54.

The relatively autonomous temporality of fields can be undermined in crisis situations or in contexts of extreme politicization, that produce synchronization effects, as previously stated. Do the transformations incurred by these situations obey past logics specific to the field of reference, as shown by studies on the French literary field during the German occupation or during the events of May 196855 ? Or, do crises, through the fluidity generated by the conjuncture, create their own dynamics, undetermined by the past states of the field56? Logics specific to crises can indeed be observed in the reshuffling of alliances and the reconfiguration of power relations that ensue. The fact remains that these transformations do not occur at random: they can be explained in light of both the specific issues at stake in the field and agents’ dispositions and resources57.

The concept of field is a powerful heuristic tool for comparison, whether it is a question of different states of the same field (for example, the French literary field before, during, and after the German occupation, or the transformations of the field of power in France between the 1970s and 1990s58), or the structuring principles of a field in two different countries. For example, the functioning of publishing in France and in the United States displays differences from the standpoint of legal organization (nonprofit publishing plays a major role in the United States, unlike in France), state intervention (virtually absent in the United States, while ubiquitous in France), and of the division of labor (for instance, in the United Stated, literary agents have largely taken over the task of selecting publishable books in addition to author representation in trade publishing, whereas in France publishers have kept these roles); nevertheless, comparing the structure of the publishing field, which in the two cases is divided between a pole of large-scale production and a pole of small-scale production, enables us to understand the place that translations hold in these two spaces59.

However, in order to avoid methodological nationalism, international comparison must take into account the exchanges between national fields as well as the power struggles in which they themselves are embedded and that determine the circulation of symbolic goods and models accross cultures. Phenomena of importation and reception must also be attributed to the specific issues at stake in the field of reception, as proven by studies on the importation of Russian formalism and Eastern European literatures into France during the communist period, or on the reception of theories of justice in this country60. A study of the introduction of the neoliberal economy and the philosophy of human rights in Latin America reveals the driving forces behind the process of globalization61.

Transnational approaches have nevertheless raised the question of the geographical limits of fields. This questioning first appeared regarding linguistic areas, and more particularly the francophone literary space62, before spreading to other transnational spaces. A number of studies on fields fall within national frameworks. However, Bourdieu never said that fields are necessarily delimited to the boundaries of the Nation State. Their borders are not fixed, they evolve over time and are constantly called into question. Consequently, they are left to the researcher to construct. The nationalization of professional fields and fields of cultural production is a historical fact linked to the monopolization of education and the State’s control of access to organized professions (to varying degrees country to country) as well as the construction of national identities63. However, these national cultures were formed in relation to each other and quickly established an international space presided over by authorities like the League of Nations, then the United Nations, and for the sector of culture and science, the International Institute of Intellectual Cooperation, taken over after the war by UNESCO , which furthered the circulation of organizational models and people between countries64. At the same time, markets were formed, whose borders considerably spilled over the edges boundaries of Nation-States, owing to their hegemonic ambitions and to colonialism (linguistic areas composed this way thus became spaces of circulation of printed works in vehicular languages such as English, French, Spanish, Portuguese, and Arabic).

Bourdieu himself analyzed the process of the emergence of a global economic field, dominated by multinational corporations and characterized by, among other things, outsourcing and capital flows65. Likewise, the legal field, closely tied to the Nation State, became thoroughly internationalized, when its heteronomous pole began to serve the interests of the market66. Though the political field remains deeply national, European construction favors the formation of a European bureaucratic field and the creation of a European legal field (even though they are still strongly dependent on Nation States)67. The emergence of more or less autonomized transnational spaces depends however on the existence of sites of exchange and specific authorities of consecration, which differentiates fields from markets – for example, international scientific conferences or the Nobel Prize in Literature68. The space of reception of symbolic revolutions also delimits a transnational space, time-span and retranslation of issues at stake from one field of reception to another being indicators of the degree of autonomy of national fields.

Besides the previously cited case of Brazil, the international reception of the concept of field took place at the end of the 1980s via specialists in French literature such as Jacques Dubois and Pascal Durand in Belgium, Joseph Jurt in Germany, Anna Boschetti in Italy, and in Israel thanks to the Polysystem theorist Itamar Even-Zohar, who combined his theory drawn from Russian formalists with field theory69. It was also used in Greece and in Russia during this time. Employed much less in the United States than the concept of habitus, the field as Bourdieu theorized it, began to serve as a research program there only after his death in 2002. The concept of field contributed notably to renewing studies on imperialism and colonialism70 : colonial States are understood in this perspective as meta-fields, which include state fields in the colonies, themselves traversed by power struggles and competition between different fractions of the colonial field of power in conflict over the definition of native policy71. The concept of field is also introduced more and more in the domain of international relations, where it is used to understand diplomatic relations as a meta-field72. In the sociology of law, a study was conducted on the field of international criminal justice, situated at the intersection of three transnational fields: interstate relations, the defense of human rights, and criminal justice, which is going through a process of internationalization73.

Organizational fields and fields of strategic

Additionally, the concept of field experienced two major theoretical reworkings, around the notions of “organization fields” and “fields of strategic action”, inspired by Bourdieu’s theory. Neo-institutional theory of “organizational fields” developed by Paul DiMaggio and Walter Powell aims to explain the phenomena of institutional isomorphism between organizations belonging to the same field74. According to them, the process of rationalization described by Weber depends now less on competition and the search for efficiency than on strictly institutional factors. Constraint (by authoritative means, legally or orders), imitation in situations of uncertainty and the normative pressures tied to professionalization are three mechanisms that foster the homogenization of these fields. It is therefore possible to predict this tendency for resemblance based on the type and degree of dependence between organizations of the same field, the degree of uncertainty as for the relations between the means and the objectives, or even the social recruitment of professionals with the same academic training and/or members of professional bodies.

The empirical studies used by these sociologists to elaborate their analysis focus on the organizational models for the production of upmarket cultural services appearing in the United States at the end of the 19th Century, and on the progressive homogenization of American academic publishing75. Paul DiMaggio, “Cultural Entrepreneurship in Ninetenth Century. Part 1. The Creation of an Organizational Base for High Culture in America”, Media, Culture and Society, n° 4, 1981, p. 33-50; Lewis A. Coser, Charles Kadushin, Walter W. Powell, Books. The Culture & Commerce of Publishing, New York, Basic Books, 1982.

Largely fueled by Bourdieu’s field theory, the concept of “fields of strategic action” developed by Neil Fligstein and Doug McAdam, combines a new institutionalist approach with collective action theories to think about the reproduction and changes taking place at the meso-level of the social order76. They take up Bourdieu’s ideas of specific stakes, rules of the game, unequal positions and the link between the actors’ position and their worldview. However, these fields of strategic action are less stabilized than Bourdieu’s fields, their boundaries shift depending on the definition of the situation and what is at stake. They can organize themselves along a continuum depending on their degree of consensus. In the case of avowed conflicts, struggles are likely to create a new order. These struggles play out primarily between “incumbents” and “challengers”, they are regulated by the “governance units” which control the functioning of the field, and tend to maintain the existing power relations within it. They can be identified as the equivalent of the consecrating authorities, or the other types of regulating bodies, whose decisive role in the fields of cultural production were emphasized by Bourdieu.

Though the model of fields of strategic action share the agonistic dimension present in Bourdieu’s theory, it more clearly distinguishes the founding principles of collective action through coercion, competition and cooperation, and therefore differentiates the fields organized hierarchically from those where different forms of coalition prevail. The question of the relationship between individuals and the field, that Bourdieu problematized with the concepts of habitus, strategy and the feel for the game, is thought of here in terms of actors’ skills at playing within a field. Far from being self-sufficient, these fields of strategic action maintain relationships with other proximate fields that differentiate themselves according to distance and proximity, independence or dependence (and in certain cases, interdependence), and the distinction between State and non-state fields – the State being understood, like in Bourdieu’s theory, as a set of fields.

Proximate fields often play a major role in change, especially through the importation of models. Transformations are frequently produced by exogenous confrontations, which offer challengers unprecedented opportunities, but they also require mobilization, the implementation of organizational resources, as well as effective means of protest. For example, Rosa Park’s refusal in 1955 to give up her seat on the bus to a white man and her ensuing arrest were not new actions in and of themselves, but the leaders of the civil rights movement with the help of ministers managed to mobilize the black community in Montgomery, Alabama in a large-scale collective protest. Throughout “episodes of contention”, one often observes recourse to innovative forms of collective action, as well as a (re)framing of the established world view, likely to lead to a new institutional settlement.

In conclusion, the concept of field is a very powerful heuristic tool for delving into the meso-level of social activity. Although different uses of the concept emerge in relation to organizational and collective action theories, that may undoubtedly enrich Bourdieu’s field theory, their scope remains more limited than Bourdieu’s. The analysis of isomorphism in the “organizational fields” must be counterbalanced by studying the processes of differentiation at work especially in the fields of cultural production77. As for the notion of “fields of strategic action”, its conceptualization is less rigorous and less historicized than the concept of field as formulated by Bourdieu. The idea of field continues, as we have seen, to function as a research program in different domains, raising new questions about colonial and transnational fields as well as the relationships between fields.

A spanish version of this entrie is accessible. See Links at the bottom of this page.

Notes

1

On these origins, see for example: John Levi Martin, “What is Field Theory?”, American Journal of Sociology, vol. 109, n° 1, 2003, p. 1-49.

2

Pierre Bourdieu, “Le marché des biens symboliques”, L’Année sociologique, n° 22, 1971, p. 49-126.

3

Bourdieu published the French translation of this book in his series “le sens commun” at the Éditions de Minuit publishing house, see Ernst Cassirer, Substance et fonction. Éléments pour une théorie du concept, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1977 (first edition 1910).

4

Pierre Bourdieu, “Quelques propriétés des champs”, in P. Bourdieu, Questions de sociologie [1980], Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1984, p. 113-120.

5

Pierre Bourdieu, “Une interprétation de la théorie de la religion selon Max Weber”, Archives européennes de sociologie, vol. XII, n° 1, 1971, p. 3-21.

6

Pierre Bourdieu, “Le marché des biens symboliques”, L’Année sociologique, n°22, 1971, p. 49-126.

7

Pierre Bourdieu, Homo academicus, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1984, p. 226-242.

8

Michel Foucault, L’Archéologie du savoir, Paris, Gallimard, 1969; Pierre Bourdieu, Raisons pratiques. Sur la théorie de l'action [1994], Paris, Le Seuil, 1996.

9

Pierre Bourdieu, “Séminaires sur le concept de champ, 1972-1975”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 200, 2013, p. 4-37; Pierre Bourdieu, “Quelques propriétés des champs”, Questions de sociologie [1980], Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1984, p. 113-120.

10

Pierre Bourdieu, “Champ intellectuel et projet créateur”, Les Temps modernes, n° 246, 1966, p. 865-906.

11

Pierre Bourdieu, “Le marché des biens symboliques”, L'Année sociologique, n°22, 1971, p. 49-126.

12

Pierre Bourdieu, Manet. Une révolution symbolique, Paris, Le Seuil-Raisons d’agir, 2013.

13

Pierre Bourdieu, Les Règles de l’art. Genèse et structure du champ littéraire, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1992.

14

Pierre Bourdieu, “La production de la croyance”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 13, 1977, p. 3-43.

15

Pierre Bourdieu, Les Règles de l’art. Genèse et structure du champ littéraire, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1992; see also: Pierre Bourdieu, “Le champ littéraire”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 89, 1991, p. 4-46, and Pierre Bourdieu, The Field of Cultural Production (éd. Randal Johnson), Cambridge, Polity Press, 1993.

16

Pierre Bourdieu, “Haute couture et haute culture” [1974-1975], in P. Bourdieu, Questions de sociologie, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1980, p. 196-206.

17

Pierre Bourdieu, “Haute couture et haute culture” [1974-1975], in P. Bourdieu, Questions de sociologie, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1980, p. 200.

18

Pierre Bourdieu, “Le champ scientifique”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 2-3, 1976, p. 88-104; Pierre Bourdieu, “The Peculiar History of Scientific Reason”, Sociological Forum, vol. 6, n° 1, 1991, p. 3-26; Pierre Bourdieu, Science de la science et réflexivité, Paris, Liber-Raisons d’agir, 2001.

19

Pierre Bourdieu, L’Ontologie politique de Martin Heidegger, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1988, p. 10; see originally: Pierre Bourdieu, “L’ontologie politique de Martin Heidegger”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 5-6, 1975, p. 109-156.

20

Pierre Bourdieu, Homo academicus, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1984.

21

Pierre Bourdieu, “Effet de champ et effet de corps”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 59, 1985, p. 73; Pierre Bourdieu, “Le fonctionnement du champ intellectual”, Regards sociologiques, n° 17-18, 1999, p. 5-27; Pierre Bourdieu, Manet. Une révolution symbolique, Paris, Le Seuil-Raisons d’agir, 2013.

22

Pierre Bourdieu, Sur l’État. Cours au Collège de France. 1989-1992, Paris, Le Seuil-Raisons d’agir, 2011.

23

Pierre Bourdieu, “Questions de politique” , Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 16, 1977, p. 55–89; Pierre Bourdieu, Propos sur le champ politique, Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon, 2000.

24

Pierre Bourdieu, La Distinction. Critique sociale du goût, Paris, Minuit, 1979.

25

Pierre Bourdieu, Sur la télévision, Paris, Liber-Raisons d’agir, 1996.

26

Pierre Bourdieu, “Une révolution conservatrice dans l’édition”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 126-127, 1999, p. 3-28.

27

For an overview, see: Gisèle Sapiro, Sociologie de la littérature, Paris, La Découverte, 2014.

28

Sergio Miceli, Les Intellectuels et le pouvoir au Brésil (1920-1945), Grenoble-Paris, Presses Universitaires de Grenoble-Éditions de la MSH, 1981 (éd. orig. 1979).

29

Rémy Ponton, Le Champ littéraire de 1865 à 1906 (recrutement des écrivains, structures des carrières et production des œuvres), thèse de doctorat de 3e cycle, Paris, Université Paris V, 1977.

30

Anne-Marie Thiesse, Écrire la France. Le mouvement littéraire régionaliste de langue française entre la Belle Époque et la Libération, Paris, PUF, 1991.

31

Gisèle Sapiro, La Guerre des écrivains. 1940-1953, Paris, Fayard, 1999.

32

Anna Boschetti, Sartre et “Les Temps Modernes”. Une entreprise intellectuelle, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1985.

33

Anna Boschetti, La Poésie partout. Apollinaire, homme-époque (1898-1918), Paris, Le Seuil, 2001.

34

Pascal Durand, Mallarmé. Du sens des formes au sens des formalités, Paris, Le Seuil, 2008.

35

Pascale Casanova, Beckett l’abstracteur. Anatomie d’une révolution littéraire, Paris, Le Seuil, 1997.

36

Rorbert Bandier, Sociologie du surréalisme. 1924-1929, Paris, La Dispute, 1999; Éric Brun, Les Situationnistes. Une avant-garde totale (1950-1972), Paris, CNRS Éditions, 2014.

37

Markus Joch, Norbert Wolf (dir.), Text und Feld. Bourdieu in der literaturwissenchaftlichen Praxis, Tubingen, Max Niemeyer Verlag, 2005; Heribert Tommek, Klaus-Michael Bodgal (dir.), Transformationen des literarischen Feldes in der Gegenwart. Sozialstruktur. Medien-Okonomien. Autorpositionen, Heidelberg, Synchron, 2012.

38

Jean-Louis Fabiani, Les Philosophes de la République, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1988.

39

Christophe Charle, Naissance des “intellectuels”. 1880-1900, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1990.

40

Frédéric Lebaron, La Croyance économique. Les économistes entre science et politique, Paris, Le Seuil, 2000.

41

Daniel Gaxie, “Les logiques de recrutement du personnel politique”, Revue française de science politique, n° 1, 1980, p. 5-45.

42

Vincent Dubois, “L’action de l’État, produit et enjeu des rapports entre espaces sociaux”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 201-202, 2014, p. 38-43.

43

See respectively: Christophe Charle, Naissance des « intellectuels ». 1880-1900, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1990; Gisèle Sapiro, La Guerre des écrivains. 1940-1953, Paris, Fayard, 1999.

44

Gisèle Sapiro, “Forms of Politicization in the French Literary Field”, Theory and society, n° 32, 2003, p. 633-652; Gisèle Sapiro, “Modèles d’intervention politique des intellectuels. Le cas français”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 176-177, 2009, p. 8-31.

45

See: Hervé Serry, Naissance de l’intellectuel catholique, Paris, La Découverte, 2004; Frédérique Matonti, Intellectuels communistes. Essai sur l’obéissance politique. La Nouvelle Critique (1967-1980), Paris, La Découverte, 2005.

46

Julien Duval, Critique de la raison journalistique. Les transformations de la presse économique en France, Paris, Le Seuil, 2004; see also: Rod Benson, Erik Neveu (ed.), Bourdieu and the Journalistic Field, Cambridge, Polity Press, 2004.

47

Alain Viala, Naissance de l’écrivain, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1985.

48

Denis Saint-Jacques, Alain Viala, “À propos du champ littéraire. Histoire, géographie, histoire littéraire”, Annales HSS, vol. 49, n° 2, 1994, p. 395-406.

49

Christian Jouhaud, Les Pouvoirs de la littérature. Histoire d’un paradoxe, Paris, Gallimard, 2000.

50

Gisèle Sapiro, “The Literary Field Between the State and the Market”, Poetics, vol. 31, n° 5-6, 2003, p. 441-461.

51

Lucia Dragomir, L’Union des écrivains. Une institution littéraire transnationale à l’Est. L'exemple roumain, Paris, Belin, 2007.

52

Julien Duval, “L’art du réalisme. Le champ du cinéma français au début des années 2000”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 161-162, 2006, p. 96-115; Julien Duval, Le Cinéma au XXe siècle: entre loi du marché et règle de l’art, Paris, CNRS Éditions, 2016.

53

Gisèle Sapiro, La Responsabilité de l’écrivain. Littérature, droit et morale en France (XIXe-XXIe siècle), Paris, Le Seuil, 2011.

54

Gisèle Sapiro, “Autonomy Revisited. The Question of Mediations and its Methodological Implications”, Paragraph, vol. 35, 2012, p. 30-48.

55

Gisèle Sapiro, La Guerre des écrivains. 1940-1953, Paris, Fayard, 1999; Boris Gobille, “Les mobilisations de l’avant-garde littéraire française en Mai 1968. Capital politique, capital littéraire et conjoncture de crise”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 158, 2005, p. 30-53.

56

Michel Dobry, Sociologie des crises politiques, Paris, Presses de la FNSP, 1992.

57

Gisèle Sapiro, “Structural History and Crisis Analysis. The Literary Field During WWII”, in P. Gorski (dir.), Bourdieu and Historical Analysis, Durham, Duke University Press, 2012.

58

Gisèle Sapiro, La Guerre des écrivains. 1940-1953, Paris, Fayard, 1999; François Denord, Paul Lagneau-Ymonet, Sylvain Thine, “Le champ du pouvoir en France”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 190, 2011, p. 24-57.

59

Gisèle Sapiro, “Globalization and Cultural Diversity in the Book Market. The Case of Translations in the US and in France”, Poetics, vol. 38, n° 4, 2010, p. 419-439.

60

See: Gisèle Sapiro, “Comparaison et échanges culturels: le cas des traductions”, in O. Remaud, J.-F. Schaub, I. Thireau, Faire des sciences sociales. Comparer, Paris, Éditions de l’EHESS, 2012, p. 193-221; Johan Heilbron, “Towards a sociology of translation. Book Translations as a Cultural World-System”, European Journal of Social Theory, vol. 2 n° 4, 1999, p. 429-444; Gisèle Sapiro (dir.), Translatio. Le marché de la traduction en France à l’heure de la mondialisation, Paris, CNRS Éditions, 2008.

61

See: Pierre Bourdieu, “Les conditions sociales de la circulation internationale des idées” [1990], Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 145, 2002, p. 3-8; Frédérique Matonti, “L’anneau de Mœbius”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 176-177, 2009, p. 52-67; Ioana Popa, Traduire sous contraintes. Littérature et communisme (1947-1989), Paris, CNRS Éditions, 2010; Mathieu Hauchecorne, “Le ‘professeur Rawls’ et le ‘Nobel des pauvres’. La politisation différenciée des théories de la justice de John Rawls et Amartya Sen”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 176-177, 2009, p. 94-113.

62

Pierre Bourdieu, “Existe-t-il une littérature belge? Limites d’un champ et frontières politiques”, Études de lettres, n° 4, 1985, p. 3-6; Paul Aron, “La littérature en Belgique francophone de 1930-1960: débats et problèmes autour d’un ‘sous-champ’”, in M. Einfalt, U. Erzgräber, O. Ette, F. Sick (dir.), Intégrité intellectuelle/Intellektuelle Redlichkeit. Mélanges en l’honneur de Joseph Jurt, Memmingen, Universitätsverlag Winter Heidelberg, 2005, p. 417-427.

63

Pierre Bourdieu, “Existe-t-il une littérature belge? Limites d’un champ et frontières politiques”, Études de lettres, n° 4, 1985, p. 3-6; Paul Aron, “La littérature en Belgique francophone de 1930-1960: débats et problèmes autour d’un ‘sous-champ’”, in M. Einfalt, U. Erzgräber, O. Ette, F. Sick (dir.), Intégrité intellectuelle/Intellektuelle Redlichkeit. Mélanges en l’honneur de Joseph Jurt, Memmingen, Universitätsverlag Winter Heidelberg, 2005, p. 417-427.

64

Gisèle Sapiro, “Le champ est-il national? La théorie de la différenciation sociale au prisme de l’histoire globale”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 200, 2013, p. 70-85.

65

Pierre Bourdieu, Les Structures sociales de l’économie, Paris, Le Seuil, 2000, p. 273-280.

66

Yves Dezalay, “The Big Bang and the Law. The Internationalization and Restructuration of the Legal Field”, Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 7, 1990, p. 279-293.

67

See: Didier Georgakakis (dir.), Le Champ de l’eurocratie. Une sociologie politique du personnel de l’UE, Paris, Economica, 2012; Antoine Vauchez, “The Force of a Weak Field. Law and Lawyer in the Government of the European Union”, International Political Sociology, n° 2, 2008, p. 128-144.

68

Pascale Casanova, La République mondiale des lettres, Paris, Le Seuil, 1999.

69

See for example: Sergio Miceli, Les Intellectuels et le pouvoir au Brésil (1920-1945), Grenoble-Paris, Presses universitaires de Grenoble-Éditions de la MSH, 1981; Jacques Dubois, Pascal Durand, “Champ littéraire et classes de textes”, Littérature, n° 70, 1988, p. 5-2; Joseph Jurt, “Autonomie ou hétéronomie : le champ littéraire en France et en Allemagne”, Regards sociologiques, n° 4, 1992, p. 3-16; Joseph Jurt. Das literarische Feld. Das Konzept Pierre Bourdieus in Theorie und Praxis, Darmstadt, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1995; Itamar Even-Zohar, “Polysystem Studies”, Poetics Today, vol. 11, n° 1, 1990, p. 1-262.

70

Julian Go, “Global Fields and Imperial Forms”, Sociological Theory, vol. 6, n° 3, 2008, p. 201-229.

71

George Steinmetz, “The Colonial State as a Social Field. Ethnographic Capital and Native Policy in the German Overseas Empire before 914”, American Sociological Review, vol. 73 n° 4, 2008, p. 589-612.

72

Didier Bigo, Michael R. Madsen (dir.), “A Different Reading of the International. Pierre Bourdieu and international studies”, International Political Sociology, vol. 5, n° 3, 2011, p. 219-224; Rebecca Adler-Nissen, “Inter- and Transnational Field(s) of Power. On a Field Trip with Bourdieu”, International Political Sociology, vol. 5, 2011, p. 327–345; Rebecca Adler-Nissen (dir.), Bourdieu in International Relations. Rethinking Key Concepts in IR, New York, Routledge, 2013.

73

Peter Dixon, Chris Tenove, “International Criminal Justice as a Transnational Field. Rules, Authority and Victims”, International Journal of Transitional Justice, 2013, p. 1-20.

74

Paul DiMaggio, Walter Powell, “The Iron Cage Revisited. Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields”, American Sociological Review, vol. 48, n° 2, 1983, p. 147-160; Paul DiMaggio, Walter Powell (dir.), The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1991.

75

Paul DiMaggio, “Cultural Entrepreneurship in Ninetenth Century. Part 1. The Creation of an Organizational Base for High Culture in America” , Media, Culture and Society, n° 4, 1981, p. 33-50; Lewis A. Coser, Charles Kadushin, Walter W. Powell, Books. The Culture & Commerce of Publishing, New York, Basic Books, 1982.

76

Neil Fligstein and Doug McAdam, A Theory of Fields, Oxford-New York, Oxford University Press, 2012.

77

Gisèle Sapiro, “How do literary works cross borders (or not)?” Journal of World Literature, vol. 1, n° 1, 2016, p. 81-96.

Bibliographie

Rebecca Adler-Nissen, “Inter-and Transnational Field(s) of Power. On a Field Trip with Bourdieu”, International Political Sociology, vol. 5, 2011, p. 327–345.

Rebecca Adler-Nissen (dir.), Bourdieu in International Relations. Rethinking Key Concepts in IR, New York, Routledge, 2013.

Paul Aron, “La littérature en Belgique francophone de 1930-1960: débats et problèmes autour d’un ‘sous-champ’”, in M. Einfalt, U. Erzgräber, O. Ette, F. Sick (dir.), Intégrité intellectuelle/Intellektuelle Redlichkeit. Mélanges en l’honneur de Joseph Jurt, Memmingen, Universitätsverlag Winter Heidelberg, 2005, p. 417-427.

Norbert Bandier, Sociologie du surréalisme. 1924-1929, Paris, La Dispute, 1999.

Didier Bigo, Michael R. Madsen (dir.), “A Different Reading of the International. Pierre Bourdieu and International Studies”, International Political Sociology, vol. 5, n° 3, 2011, p. 219-224.

Rod Benson, Erik Neveu (dir.), Bourdieu and the Journalistic Field, Cambridge, Polity Press, 2004.

Anna Boschetti, Sartre et “Les Temps Modernes”. Une entreprise intellectuelle, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1985.

Anna Boschetti, La Poésie partout. Apollinaire, homme-époque (1898-1918), Paris, Le Seuil, 2001.

Pierre Bourdieu, “Champ intellectuel et projet créateur”, Les Temps modernes, n° 246, 1966, p. 865-906.

Pierre Bourdieu, “Genèse et structure du champ religieux”, Revue française de sociologie, t. XII, 1971, p. 295-334.

Pierre Bourdieu, “Une interprétation de la théorie de la religion selon Max Weber”, Archives européennes de sociologie, vol. XII, n° 1, 1971, p. 3-21.

Pierre Bourdieu, “Le marché des biens symboliques”, L'Année sociologique, n° 22, 1971, p. 49-126.

Pierre Bourdieu, “L’ontologie politique de Martin Heidegger”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 5-6, 1975, p. 109-156.

Pierre Bourdieu, “Le champ scientifique”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 2-3, 1976, p. 88-104.

Pierre Bourdieu, “La production de la croyance”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 13, 1977, p. 3-43.

Pierre Bourdieu, “Questions de politique”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 16, 1977, p. 55–89.

Pierre Bourdieu, La Distinction. Critique sociale du goût, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1979.

Pierre Bourdieu, “La représentation politique”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 36-37, 1981, p. 3–24.

Pierre Bourdieu, Homo academicus, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1984.

Pierre Bourdieu, Questions de sociologie [1980], Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1984.

Pierre Bourdieu, “Effet de champ et effet de corps”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 59, 1985, p. 73.

Pierre Bourdieu, “Existe-t-il une littérature belge? Limites d’un champ et frontières politiques”, Études de lettres, n° 4, 1985, p. 3-6.

Pierre Bourdieu, L’Ontologie politique de Martin Heidegger, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1988.

Pierre Bourdieu, “Le champ littéraire”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 89, 1991, p. 4-46.

Pierre Bourdieu, “The Peculiar History of Scientific Reason”, Sociological Forum, vol. 6, n° 1, 1991, p. 3-26.

Pierre Bourdieu, Les Règles de l'art. Genèse et structure du champ littéraire, Paris, Le Seuil, 1992.

Pierre Bourdieu, The Field of Cultural Production (éd. Randal Johnson), Cambridge, Polity Press, 1993.

Pierre Bourdieu, Raisons pratiques. Sur la théorie de l'action [1994], Paris, Le Seuil, 1996.

Pierre Bourdieu, Les Usages sociaux de la science, Paris, INRA, 1997.

Pierre Bourdieu, “Le fonctionnement du champ intellectuel”, Regards sociologiques, n° 17-18, 1999, p. 5-27.

Pierre Bourdieu, “Une révolution conservatrice dans l'édition”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 126-127, 1999, p. 3-28.

Pierre Bourdieu, Propos sur le champ politique, Lyon, Presses universitaires de Lyon, 2000.

Pierre Bourdieu, Les Structures sociales de l’économie, Paris, Le Seuil, 2000.

Pierre Bourdieu, Science de la science et réflexivité, Paris, Liber-Raisons d’agir, 2001.

Pierre Bourdieu, “Les conditions sociales de la circulation internationale des idées” [1990], Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 145, 2002, p. 3-8.

Pierre Bourdieu, Sur l’État. Cours au Collège de France. 1989-1992, Paris, Le Seuil-Raisons d’agir, 2011.

Pierre Bourdieu, “Séminaires sur le concept de champ, 1972-1975”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 200, 2013, p. 4-37.

Pierre Bourdieu, Manet. Une révolution symbolique, Paris, Le Seuil-Raisons d’agir, 2013.

Éric Brun, Les Situationnistes. Une avant-garde totale (1950-1972), Paris, CNRS Éditions, 2014.

Pascale Casanova, Beckett l’abstracteur. Anatomie d’une révolution littéraire, Paris, Le Seuil, 1997.

Pascale Casanova, La République mondiale des lettres, Paris, Le Seuil, 1999.

Pascale Casanova, Kafka en colère, Paris, Le Seuil, 2011.

Ernst Cassirer, Substance et fonction. Éléments pour une théorie du concept, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1977 (éd. orig. 1910).

Christophe Charle, Naissance des “intellectuels”. 1880-1900, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1990.

Lewis A. Coser, Charles Kadushin, Walter W. Powell, Books. The Culture & Commerce of Publishing, New York, Basic Books, 1982.

François Denord, Paul Lagneau-Ymonet, Sylvain Thine, “Le champ du pouvoir en France”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 190, 2011, p. 24-57.

Yves Dezalay, “The Big Bang and the Law. The Internationalization and Restructuration of the Legal Field”, Theory, Culture & Society, vol. 7, 1990, p. 279-293.

Yves Dezalay, “Les courtiers de l'international. Héritiers cosmopolites, mercenaires de l'impérialisme et missionnaires de l'universel”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 151-152, 2004, p. 4-35.

Yves Dezalay, Bryant G. Garth, The Internationalization of Palace Wars. Lawyers, Economists, and the Contest to Transform Latin American States, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2002.

Yves Dezalay, Michael R. Madsen, “The Force of Law and Lawyers. Pierre Bourdieu and the Reflexive Sociology of Law”, Annual Review of Law and Social Science, n° 8, 2012, p. 433–452.

Paul DiMaggio, “Cultural Entrepreneurship in Ninetenth Century. Part 1. The Creation of an Organizational Base for High Culture in America”, Media, Culture and Society, n° 4, 1981, p. 33-50.

Paul DiMaggio, Walter Powell, “The Iron Cage Revisited. Institutional Isomorphism and Collective Rationality in Organizational Fields”, American Sociological Review, vol. 48, n° 2, 1983, p. 147-160.

Paul DiMaggio, Walter Powell (dir.), The New Institutionalism in Organizational Analysis, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1991.

Peter Dixon, Chris Tenove, “International Criminal Justice as a Transnational Field. Rules, Authority and Victims”, International Journal of Transitional Justice, 2013, p. 1-20.

Michel Dobry, Sociologie des crises politiques, Paris, Presses de la FNSP, 1992.

Lucia Dragomir, L’Union des écrivains. Une institution littéraire transnationale à l'Est. L'exemple roumain, Paris, Belin, 2007.

Jacques Dubois, Pascal Durand, “Champ littéraire et classes de textes”, Littérature, n° 70, 1988, p. 5-2.

Vincent Dubois, “L’action de l’État, produit et enjeu des rapports entre espaces sociaux”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 201-202, 2014, p. 38-43.

Pascal Durand, Mallarmé. Du sens des formes au sens des formalités, Paris, Le Seuil, 2008.

Julien Duval, Critique de la raison journalistique. Les transformations de la presse économique en France, Paris, Le Seuil, 2004.

Julien Duval, “L'art du réalisme. Le champ du cinéma français au début des années 2000”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 161-162, 2006, p. 96-115.

Julien Duval, Le Cinéma au XXe siècle: entre l’art et l’argent, Paris, CNRS Éditions, 2016.

Itamar Even-Zohar, “Polysystem Studies”, Poetics Today, vol. 11, n° 1, 1990, p. 1-262.

Jean-Louis Fabiani, Les Philosophes de la République, Paris, Éditions de Minuit, 1988.

Neil Fligstein, Doug McAdam, A Theory of Fields, Oxford-New York, Oxford University Press, 2012.

Michel Foucault, L’Archéologie du savoir, Paris, Gallimard, 1969.

Daniel Gaxie, “Les logiques de recrutement du personnel politique”, Revue française de science politique, n° 1, 1980, p. 5-45.

Didier Georgakakis (dir.), Le Champ de l’eurocratie. Une sociologie politique du personnel de l’UE, Paris, Economica, 2012.

Julian Go, “Global Fields and Imperial Forms”, Sociological Theory, vol. 6, n° 3, 2008, p. 201-229.

Boris Gobille, “Les mobilisations de l’avant-garde littéraire française en Mai 1968. Capital politique, capital littéraire et conjoncture de crise”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 158, 2005, p. 30-53.

Mathieu Hauchecorne, “Le ‘professeur Rawls’ et ‘le Nobel des pauvres’. La politisation différenciée des théories de la justice de John Rawls et Amartya Sen”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 176-177, 2009, p. 94-113.

Johan Heilbron, “Towards a sociology of translation. Book Translations as a Cultural World-System”, European Journal of Social Theory, vol. 2, n° 4, 1999, p. 429-444.

Markus Joch, Norbert Wolf (dir.), Text und Feld. Bourdieu in der literaturwissenchaftlichen Praxis, Tubingen, Max Niemeyer Verlag, 2005.

Christian Jouhaud, Les Pouvoirs de la littérature. Histoire d’un paradoxe, Paris, Gallimard, 2000.

Joseph Jurt, “Autonomie ou hétéronomie: le champ littéraire en France et en Allemagne”, Regards sociologiques, n° 4, 1992, p. 3-16.

Joseph Jurt. Das literarische Feld. Das Konzept Pierre Bourdieus in Theorie und Praxis, Darmstadt, Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft, 1995.

Frédéric Lebaron, La Croyance économique. Les économistes entre science et politique, Paris, Le Seuil, 2000.

John Levi Martin, “What is Field Theory?”, American Journal of Sociology, vol. 109, n° 1, 2003, p. 1-49.

Frédérique Matonti, Intellectuels communistes. Essai sur l’obéissance politique. La Nouvelle Critique (1967-1980), Paris, La Découverte, 2005.

Frédérique Matonti, “L’anneau de Mœbius”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 176-177, 2009, p. 52-67.

Sergio Miceli, Les Intellectuels et le pouvoir au Brésil (1920-1945), Grenoble-Paris, Presses Universitaires de Grenoble-Éditions de la MSH, 1981 (éd. orig. 1979).

Rémy Ponton, Le Champ littéraire de 1865 à 1906 (recrutement des écrivains, structures des carrières et production des œuvres), thèse de doctorat de 3e cycle, Paris, Université Paris V, 1977.

Ioana Popa, Traduire sous contraintes. Littérature et communisme (1947-1989), Paris, CNRS Éditions, 2010.

Denis Saint-Jacques, Alain Viala, “À propos du champ littéraire. Histoire, géographie, histoire littéraire”, Annales HSS, vol. 49, n° 2, 1994, p. 395-406.

Gisèle Sapiro, La Guerre des écrivains. 1940-1953, Paris, Fayard, 1999.

Gisèle Sapiro, “Forms of Politicization in the French Literary Field”, Theory and Society, n° 32, 2003, p. 633-652.

Gisèle Sapiro, “The Literary Field Between the State and the Market”, Poetics, vol. 31, n° 5-6, 2003, p. 441-461.