(Inalco / EHESS - Institut français de recherches sur l’Asie de l’Est / Centre de recherches sur le Japon)

The national museum of ethnology in Japan (Kokuritsu minzokugaku hakubutsukan, hereafter the Minpaku) was founded in 1974, and opened its doors to the public in 1977. It was not a renovation of a pre-existing institution, but rather the first national museum of ethnology (both a museum and a research center). In November 1977, Umesao Tadao (1920-2010) – the charismatic first director of the Minpaku who played a decisive role in its creation – responded to a journalist’s question about the new museum’s stance towards Western institutions in the following terms:

Our institution is on a different theoretical plane [to these colonial museums]. It is a world first. In going beyond the national, and sweeping colonial ideology away, we think of ourselves within a new world order1.

In a few words, revelatory of how Western museum institutions were perceived, Umesao Tadao erases the relationship between colonial phenomena and ethnology as it developed in Japan. But was the Minpaku museography truly foreign to this past? May we deem the Minpaku’s exhibition practices to be “postcolonial”, in the sense of being a critique of this form of domination2?

Placing Japanese ethnology in historical perspective casts light on the museum’s ambiguous relationship to Japan’s colonial legacy as this transpired in its initial museographic program. In what terms was the Other placed on display at the Minpaku, in a supposed “year zero” of Japanese ethnographic scholarship’s representation of alterity? The case of the exhibits of a national ethnic minority, the Ainu, brings out certain limits to this institution’s museographic and museum choices.

Silencing which past? And above all how?

Which past practices did the museum decide not to take into consideration? Did Japanese ethnology undergo a particular development enabling the Minpaku to place itself on a “different theoretical plane”?

The development of a discipline and birth of a museum

Ethnological scholarship developed in Japan in the late nineteenth century, when the country opened its maritime borders, which had been virtually closed for over two centuries. Western knowledge spread through the archipelago, and many foreign specialists were invited to come and teach new learning, including anthropology, or more specifically the natural sciences. It was the American naturalist Edward Sylvester Morse (1838-1925) who, as of 1878, laid the groundwork for the natural sciences, anthropology, and archaeology in Japan, at the biology department in the faculty of science at the Imperial University of Tokyo (nowadays the University of Tokyo), which had just been founded in 1877. In 1884, the first learned society was established by students gravitating around this university, the Friends of anthropology (Jinruigaku no tomo), which went on to become the present-day Japanese society of anthropology (Nihon jinrui gakkai). One of the lasting characteristics of anthropological and ethnological scholarship in Japan is the interest for the archipelago’s culture and its origins3. In the late nineteenth century, it was primarily a matter of (re)appropriating this field of research so as not to leave it in the hands of foreign anthropologists, for fear of being reduced to an object of study.

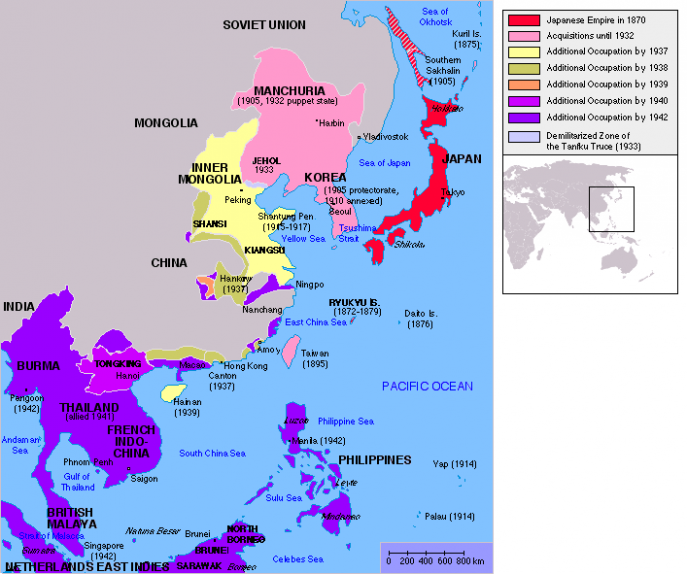

Map of the Japanese empire

Numerous field studies were soon carried out in Asia, with scholarship turning towards continental cultures as Japan progressively extended its colonial empire. The first territories absorbed into the Japanese Empire were Hokkaido, the Ryukyu Islands (the present-day province of Okinawa), followed by Taiwan (1895), then the Korean Peninsula (1910). As for the region of Manchuria, it gave rise to a puppet state, Manchukuo. This was followed by the occupation of southeast Asia, and of the eastern Pacific. The boundaries between the human sciences were initially slight, but as of the late 1920s two tendencies emerged as a result of field observations outside the metropole. These were physical anthropology (keishitsu jinrui-gaku 形質人類学) at the Imperial University of Tokyo, and ethnology (minzoku-gaku 民族学),4 which became formalized with the setting up of the Society for the study of ethnology (Nihon minzoku gakkai) with its own journal, founded in 1934.

Anthropological and ethnological work – with a pronounced archaeological dimension – examining populations in these colonized regions or places under Japanese influence was carried out in imperial colonial universities or else associated with museum institutions:

These museums and the scientific research they conducted participated in legitimizing colonial conquest, stressing shared historical and cultural roots with Japan (as is the case for the Korean Peninsula), or else building up a historical narrative that downplayed Chinese influence (in the case of Manchuria). Additionally, they responded to a desire to develop precise knowledge about colonized territories and cultures which could help the colonial endeavor. The purpose of these institutions was to create a feeling of deference towards the Japanese Empire, placed at the summit of the hierarchy of Asian peoples. At the same time, they compared continental cultures to Japan (a close Other), in an endeavor to build up a multi-ethnic empire,7 meant to “liberate” eastern Asia from Western thralldom. Additionally, in 1942 a public institute was set up in the Tokyo district of Akasaka, the Centre for ethnological study (Minzoku kenkyū-jo), though it was very short-lived (1942-1945).

Still, Japan held back from establishing a national museum of the sort found in European nations. A projected ethnology museum, plans for which were presented in 1936, did not see the light of day, nor did a museum of greater eastern Asia devised in the early 1940s, based in the metropole and with annexes on the continent8. This was not due to any lack of interest in material culture or in building up collections, the Imperial University’s research unit having gathered many Japanese and foreign objects (now held in the Minpaku). A museum with links to the Japanese society of ethnology opened to the public from 1939 to 1952 (with a hiatus at the end of the war)9. The collections of the museums in Taiwan and Korea, however, remained where they were – after capitulating Japan lost all its empire, causing the colonizers to return hastily to the metropole. To complete this overview, the national museum in Tokyo also had an ethnographic collection, as did the Tenri museum (Tenri sankō-kan) whose collections were comprised mostly of donations, legacies, and items collected during ethnographic missions.

Given the diversity of these museums, it is difficult to provide a general overview of how their ethnographic collections were exhibited. The museum annexed to the society for the study of ethnology had few visitors. The national museum in Tokyo was rebuilt after the 1923 earthquake, with a change of focus on fine arts exhibitions10. In the absence of any national museum of ethnology, it was industrial and colonial exhibits and museums built in regions under Japanese domination that no doubt came closest to exhibiting humanity.

The 5th national industrial exhibition (Dai go kokunai kōgyō hakurankai) held in 1903 in the Osaka District of Tennōji was the first in which the Imperial University of Tokyo anthropology unit was involved. It was also the first exhibition of Japan as a colonial empire11, even though it was not until the 1912 exhibition in Ueno that the term takushoku (the equivalent of “colonial”12) was taken up in the name of the event. In 1903, an anthropological pavilion (Gakujutsu jinrui-kan) made its first appearance, coordinated by the anthropology department. Ethnographic objects collected in various regions were on display, accompanied by a map of the different human races drawn up by Tsuboi Shōgorō (1863-1913) – a key figure in the department at the Imperial University of Tokyo, and in the history of Japanese anthropology13. This pavilion viewed the regions under Japanese domination in hierarchical terms. In addition to objects, “natives from the colonies” in Taiwan, Korea, Malaysia, Java, and China were exhibited14. Japan thus positioned itself among the “civilized” powers facing countries peopled with “savages” (yaban-jin). The anthropology unit’s involvement in the exhibition lent scientific credibility to this discriminating discourse15. The 1903 exhibition thus followed in the footsteps of Western universal and subsequently colonial exhibitions.

The following year, the unit staged an “exhibition of anthropological specimens” (Jinruigaku hyōhon hakurankai) on its own premises. This presented five Asiatic “ethnic groups” (shuzoku), each represented by objects (arms, costumes, etc.) and photographs16. The exhibition presented these people close to Japan as belonging to a time that was now past, with objects from the Japanese Stone Age being exhibited as a comparison, thereby signifying that these other cultures were “backwards”.

In short, there was nothing atypical about Japan at this time. The reifying vision this type of exhibition presented of the Asiatic other and the contribution made by anthropology – and later ethnology – to legitimizing colonial conquest operated in broadly similar manner to what may be observed in the West. In the 1960s, however, calls to create a national museum of ethnology re-emerged in what was now a non-colonial context. In the intermediary period, identity discourse had undergone a complete reversal: after the country’s defeat, the Japanese multi-ethnic empire had been replaced by the myth of an ethnically and culturally homogenous Japan.

An “a-colonial” museum without postcolonial critique

When at the end of the 1960s preparations began for a national museum of ethnology in Japan, Western ethnology museums were confronted with a world that was very different from that of their origins, with new voices and demands emerging due to decolonization and the advent of Third World. They became the privileged target of a body of critical scholarship soon baptized “postcolonial”17. At the same time, museum facilities were ageing, leading disaffected researchers to turn to universities. The utility and legitimacy of museums as an institution was thus called into question. How may we explain the birth of a national museum of ethnology in Japan in such an inauspicious context?

The situation differed, first, in that Japan did not have an existing ethnology museum around which criticism could coalesce. The Minpaku did not inherit a museum history which might have made it necessary to redefine its purpose. Nor did it inherit any sizeable collections, most of the objects on display issuing from recent collecting (one third of the museum’s holdings in 1977 had been collected for its museographic needs during the few years preceding its opening). These two characteristics meant it could be presented as a “new” “year zero” museum18, apparently relieved of memorial responsibility. In Japan it was, rather, scientific institutions that were confronted with ethical questions about restituting human bones (notably to the Ainu)19. So despite similarities between the history of Japanese and Western anthropologies, the museum was designed in a different ideological framework to European ethnology museums if only for reasons of date. Despite renovating their exhibition rooms, the latter still conveyed the image of a disciplinary and museographic tradition marked by a hierarchical vision of the world – something they are still faced with today. Placed within the sole context of its creation, the Minpaku freed itself of a legacy that it nevertheless shares with the West.

It should nonetheless be pointed out that the anthropology unit’s collections are part of the Minpaku’s holdings, and, additionally, that the museum of the Japanese society of ethnology is considered by the Minpaku as its symbolic forerunner. Moreover, when calls were made after the war to create an ethnology museum, this filiation was emphasized and frequently repeated. At the time it was a way of avoiding any comparison with the Center for ethnological study, set up to participate in the colonial endeavor and which, despite its short-lived existence, contributed to the perception of ethnology as a science that had collaborated in the war to invade the Asiatic continent20. This was not the case of the Japanese society of ethnology (1934) and its museum established in 1939 thanks to collections ceded by the Attic museum – a learned society interested in studying the material culture of the archipelago – whose members joined the new society21. It was restructured in 1942 as the Japanese association of ethnology, becoming an auxiliary support organization of the Center for ethnological study. Nevertheless, it had all but interrupted its museum activities during this period (apart from classification and the publication of a review). Equally, in 1942 the members of the Attic museum had reorganized around the Japanese popular culture research institute (Nihon jōmin bunka kenkyūjo). Hence the Japanese society of ethnology museum and its collections were associated with studying material culture rather than the colonial endeavor. The fact that the Japanese society for ethnology, the driving force behind the Minpaku, adopted a strategy of symbolic association with the Attic museum reveals a determination to occult part of the history of the discipline, namely that of the colonial period. This is similarly displayed by the society’s laying claim to the Attic museum’s collections despite other learned societies having previously promoted a project for a national folklore museum. The museum aspect of the planned institution was foregrounded, even though those promoting the Minpaku were probably thinking more in terms of a national research institute.

The lack of debate about the ethnographic sciences and Japan’s colonial past when the Minpaku was founded (and during the following decades even) may also be attributed to the paucity of scholarship criticizing museums, particularly “postcolonial” critique. Even after Edward Saïd’s pioneering Orientalism was translated into Japanese in 1986, post-colonialism still struggled to develop. Drawing on work by Arnaud Nanta, a specialist in the historiography of the Japanese colonial period, the following hypothesis may be made: although research on colonialism as a form of domination emerged in Japan in the 1960s, this was overlaid by the end of the Second World War and the loss of the colonial empire, meaning that work on this period “eclipsed the colonial empire due to over-focusing on the nature of the regime, that is to say on the ‘imperial system”22. Anthropology students at the University of Tokyo, borne along by the May 1968 student movements, nevertheless denounced the potentially ideological dimension to the Minpaku, holding the institution to be “an integral part of the colonial and imperialist ideology of the Japanese government”23. Yet this was only a marginal reaction. Scholarship on the ideological dimension to the museum, and how this related to the building of the Japanese nation-state and the constitution of its “colonial” empire, mostly only really took off as of the 2000s24. The same is true of works about the history of ethnology and its centers of learning (including museums) in the Empire. There are now an increasing number of academic works examining the history of science and the historiography of ethnology as a discipline. They view the anthropological sciences as colonial technologies, exploring how they partook in building alterity and the nation-state25. Admittedly, the Minpaku did not itself partake in constructing alterity during the colonial period, but even today there are still no debates about the utility of such an institution. While Jean Jamin in France wondered back in 1998 whether we should “burn down ethnography museums”, the absence of any such critical literature in Japan raises legitimate questions.

Birth of a year-zero museography

So what does the Minpaku – which has placed itself “on a different theoretical plane” and “swept away” colonial ideology – in fact look like. What “a-colonial” processes and techniques does it use to exhibit humanity?

The exhibition program is based around two interlinked ideas. First, the museography should reflect the findings of the comparative ethnology research unit that is part of the museum. There are no curators at the Minpaku, it is researchers who devise the museography. Second, the project is to present foreign cultures evenhandedly, in a cultural relativism rid of the colonial legacy. The aim is therefore to avoid imposing any ethnocentric vision, any hierarchy of cultures, but instead to compare them in a way that emphasizes their singularity and thus establishes proximity, rather than distance which generates exotic representations. How does this cultural relativism advocated by the museum transpire?

“Typically Japanese”? De-partitioning space to de-partition cultures

The first point to make concerning museum choices is that the Minpaku does not seek an aestheticized presentation of its collections. It uses a certain number of photos, maps, and technologies (such as video booths) in the exhibition space. Objects are laid out in series, often alongside full-scale or miniature reconstitutions of habitats, sometimes including their external environment. These choices are attributable to reasons specific to the institutional and disciplinary context in Japan, but should not thereby be seen as a Japanese characteristic26. The Minpaku has no model or antecedent on which to ground its museography. It seeks to distinguish itself from the museography of other national fine arts-type museums in Japan (through its choice of a non-aestheticizing presentation). It borrows from the Western models visited by those who worked on its preparatory project, as well as from the exhibition of the museum of the Japanese society for ethnology, notably in its use of models. Yet architecturally, the proposals are “typically Japanese”.

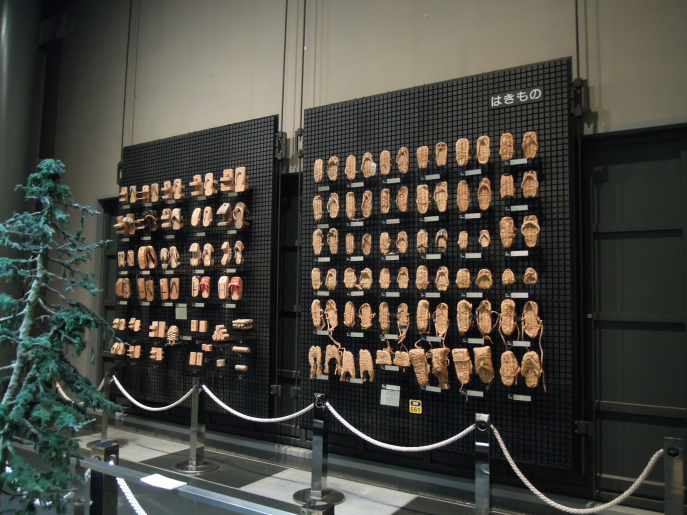

on the left: typical layout of the north area of Honshû

kept at the Minpaku museum in the space dedicated to the japanese culture (Minpaku, june 2011)

on the right: exhibition of shoes (Minpaku, june 2011)

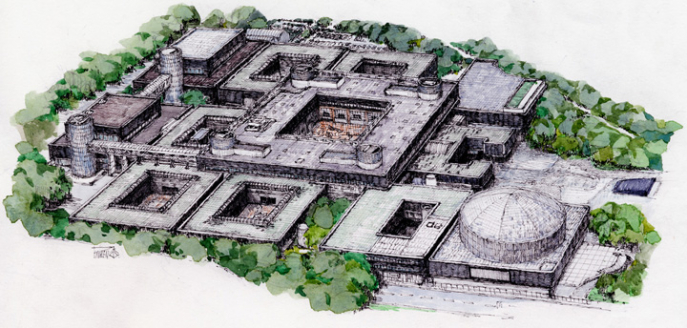

Kurokawa Kishō (1934-2007) was the head architect for the Minpaku, which benefited from a new building. He was one of the young founders of the “Metabolism” current in architecture (1959-1975). This group suggested creating towns and buildings that could evolve and thus adapt to societal transformations and population increase. The Minpaku is a clear illustration of this movement, which developed mostly in Japan. While the architecture generally reflects the function of the building as a museum and a place of science, what distinguishes the Minpaku is the concern to reflect specifically “Umesao’s anthropology” (Umesao jinruigaku) – the key figure behind the museographic choices of the Minpaku – and to differentiate it from Western museums via new architectural options. In other terms, the architecture seeks to translate the principle of cultural relativism via which the Minpaku, presenting itself as an “indigenous” museum, sought to break with Western museums27.

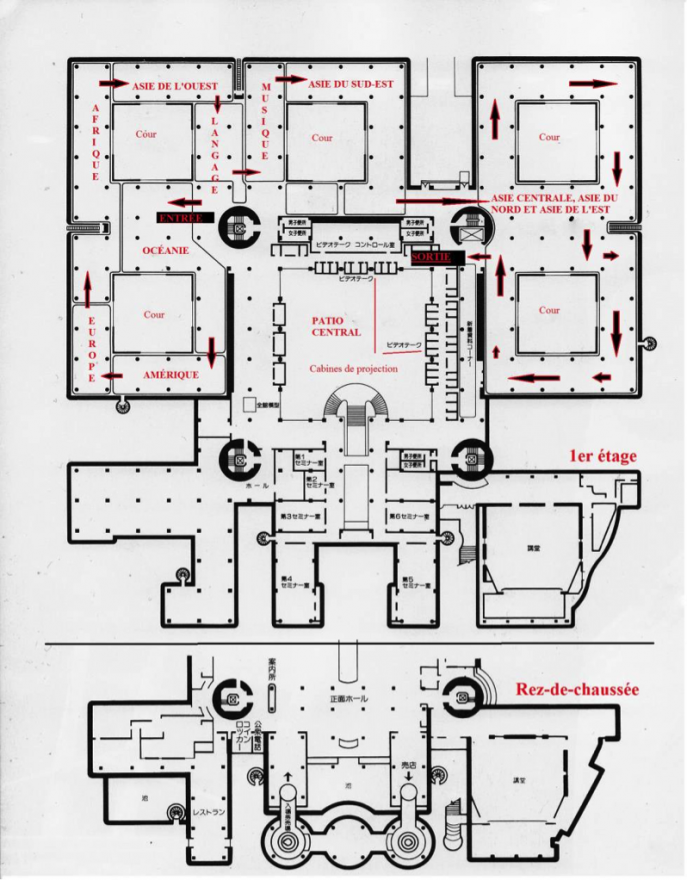

Plan of the permanent exhibition in 1981, Minpaku

The clearest architectural translation of this museum concept is its structure, based on lattice modules. The museum is built around a central patio, associating several autonomous modules, within which a system of lattices makes it possible to modify the space, partitioning it off or opening it up depending on needs. The building is not an entity made up of a single unit, but an evolving modular construct. Kurokawa compared this form to the architecture of tea pavilions (chashitsu), in opposition to pyramidal Western architecture with its hierarchic spaces. In this way the structure of the museum coincides with how cultures are exhibited. The architecture does not impose any fixed or settled interpretation. Another of Kurokawa’s ideas was to think of the exhibition space as a circuit or “circulation” (kaiyû-shiki), rather than as a partitioned pathway with a fixed beginning and end. On this point he contrasted the law of perspective in Europe, which tends to think of buildings and structures from a single perspective, with the plurality said to predominate in Japan. The circuit through the exhibition provided a way of foregrounding the diversity of interpretations and points of view. Similarly, it was decided to cover the indoor and outdoor space in black to avoid creating any demarcation, thus retaining a visual unity across all the regions on display28

Draw of an overhead view of Minpaku, 2016

Gallery dedicated to the Chinese regions, Minpaku (juin 2011)

“Moving beyond the national” in a “new global ordering”

The way the permanent exhibition divides up the world reflects the desire to treat cultures equally and without any hierarchy. The rooms of the Minpaku are divided into several large zones, each representing a continent – apart from Asia, which is divided into subsets. The museum calls these “regions” (chiiki), in reference to very broad geographical divisions that do not correspond to any political, cultural, or ethnic entity. Indeed, ethnic units, for example, run the risk of conveying reifying discourse, for they draw on ethnic names or cultural groups which do not correspond to reality, or else are marked by learning dating from the colonial period. Similarly, it shuns borders between countries, for these reflect political or administrative units rather than cultural or ethnic ones. Hence the zones or “regions”, each organized into themes, make it possible, the Minpaku argues, to break free from any ideological delimitation of the world. The absence of subdivisions by ethnic group or culture in each zone or region also brings to light resemblances or differences within and between exhibition spaces.

The circuit through the permanent exhibition circles the world from East to East. It starts with Oceana, passing through the Americas, Europe, and Africa, continuing across western Asia, central Asia, northern Asia, and south-eastern Asia, before finishing in eastern Asia. All the regions of the world are represented, and the way the circuit unfolds geographically does not presuppose any evolutionist vision or any superior cultural reach of one region over another. The presence of Europe and of Japan among the various regions of the world symbolizes the Minpaku’s wish to place all cultures on an equal footing, thus distancing itself from any Eurocentric or ethnocentric vision. Integrating Japan within the exhibition circuit offers a way of positioning the national culture in comparison to other countries, linked to the idea that ethnocentrism disappears once the country presenting the exhibit includes itself in the display.

These choices partly result from visits by members of the Minpaku preparatory committee to Western ethnology museums. The presence of Europe, for example, comes across as a response to the way Japanese culture is treated exotically, often immobilized in the past, as observed by committee members during their travels around the Europe. One of them, Inui Susumu, from the agency for cultural affairs, ironically summarized the reasons for this choice as follows:

Europeans, as the peoples elected by the gods, present themselves as the main protagonists in the study of cultures other than those belonging to the European race (jinshu), who lag behind their civilization. Apparently, it has not occurred to them that they could in turn be objects of study. Nevertheless, from the point of view of cultural anthropology, there is no reason why not. The fact that Umesao and his teams are currently conducting a full scientific survey of the indigenous populations (genjûmin) of the Mediterranean region of Europe reflects this way of thinking29.

The Minpaku’s attitude towards the West partakes in this repositioning of Japan on the international scene. Whether consciously or not, it reflects discourse about the cultural specificity of Japan (Nihon bunka-ron 日本文化論) – and of “Japan-ness” in general – which developed as of the 1960s, rather than any specifically “postcolonial” critique. These writings peaked during the following two decades, coinciding with the country’s spectacular economic growth. They explain this success in terms of endogenous culturalist characteristics30. This body of literature, in which the humanities and social sciences took part, puts forward an interpretation of Japan’s psychology, culture, society, and history centered on a particularism built up and developed in contradistinction to the West. It takes the opposing stance to Saïd’s Orientalism, as it were, replaced by a Westernism31. In calling for a totally different type of museum to be established, distinct from those in the West, the Minpaku, whether voluntarily or not, falls in with this current of thought.

There is undeniably an aspect of this discourse that is eminently critical of Western hegemony. It could be compared to a postcolonial stance given the blanket rejection by Minpaku staff – starting with its director – of the system to produce Western knowledge, which builds up an exotic image of foreign populations. A similar stance transpires in its architectural choices. Nevertheless – and herein lies the Minpaku’s paradox, and a certain schizophrenia even – without having been colonized by the West, Japan was a colonizer itself, producing an exotic vision of the Other. Besides, Japan’s particular status may be detected in the way the West views the archipelago’s culture, presented in art museums rather than anthropology museums, and prized in comparison to that of other populations deemed “savage”.

Comparing in order to relativize. Fine, but how?

The permanent exhibition uses region-specific themes to approach the cultures in each region, rather than systematic ones used, for example, at the Musée de l’Homme where each display case seeks to reconstitute a “way of life as a whole”, an isolated “cultural totality”32. The approach prevents any unique interpretive framework being imposed on the cultures on display, keeping the flaws of universalist ambition at bay. But it has the drawback of making it difficult to compare cultures. The overrepresentation of Asiatic regions, a reflection of the fields privileged by Japanese ethnological scholarship, reveals the limits of this museography. While the exhibition yokes numerous cultures together within certain geographical areas (Oceana, Africa, Europe, etc.), eastern Asia is subdivided into three more limited territories, virtually amounting to national units (the Korean Peninsula, the Chinese regions, and Japan). This dissymmetry stymies comparison. Any work to place cultures in perspective is left to the appreciation of visitors, apart from two cross-cultural exhibition spaces placed mid-circuit, the first devoted to music and the second to language.

on the left: intercultural space of exhibition dedicated to music (picture 2019)

on the right: intercultural space of exhibition dedicated to langage (picture 2019)

The second limit to this museographic choice is its very extensive recourse to the “traditional” order, supposedly characteristic of the societies on display. Yet the desire to scientifically exhibit foreign cultures without reproducing the flaws of exoticizing representation could have led to adopting the shin-kyû-to-hi exhibition principle, invented when the program was being drawn up for the museum. This refers to exhibiting the new (shin) and the old (kyû), the urban (to) and the rural (hi), in order to dynamically represent foreign cultures. But the urgency with which items were collected over just a few years prevented this method from being fully applied. It was however one of the most interesting and innovative of the Minpaku’s suggestions, and may be seen as a further attempt to differentiate itself from the West.

The concern with fully retaining the specific characteristics of the cultures on display (presumably in opposition to the universalist ambitions of Western museums), extensively undermines the process of placing them in perspective, meant to be the first step in enacting the principle of cultural relativism. Ultimately, rather than a year-zero museography, the Minpaku follows a museography of substitution. Colonial and neocolonial ideology is replaced by cultural relativism, and questioning the West is prioritized over any critique of the Minpaku’s own practices.

Exhibiting Japanese ethnic minorities: the limits to an “ideology-free” approach

Umesao went so far as to speak of a museum that was “ideology-free” (ideorogî furî)33. The failure to take the colonial legacy into account is clearly not problematic for regions which have not been dominated or even studied by Japanese ethnology. But what about other regions, and particularly, to take a specific example, Ainu culture? The Ainu are a Japanese ethnic minority whose territory consists of the island of Hokkaido, the island of Sakhalin, the Kuril Islands, and the far east of Siberia. Hokkaido was annexed in 1869, and remained Japanese after 1945. The Ainu have been subjected to a brutal assimilation policy, and only very recently considered by Japan as the indigenous people of Hokkaido (in 2008), after demands were taken up internationally in the wake of the 2007 UN declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples.

The fate of the Ainu was closely bound up with the advent of the Japanese nation-state, which constituted itself as an empire. The anthropological sciences have paid particular attention to this “close Other”, whose culture was put on display notably during the 5th national industrial exhibition in 1903, and the Saint Louis world fair in 1904. The way the Ainu, their culture, and their origins have been represented has fluctuated with successive ideologies. From the outset, anthropologists researching the origins of Japan looked at these northern settlements. The Ainu were perceived as issuing from a settlement predating the Japanese (said to have pushed these earlier people northwards), or else as living proof of an earlier stage (close to the Stone Age) in the evolution of the Japanese34. Research focused primarily on their racial origins and on their relations with Japanese settlements35. They were viewed as “barbarians” (Yaban-jin), in opposition to the civilized Wajin (Japanese).

Admittedly, the Ainu became Japanese in 1869 – although discriminated against and referred to as kyûdojin (former aborigines) from 1878 to 1997. But their culture was perceived as archaic, in need of civilizing by making it more like Japanese culture. The assimilation policy, introduced in 1872, obliged them to become farmers – thereby precluding their hunting and fishing activities –, and sought to “minimize” (mikuro-ka) differences between Japanese and Ainu culture. As of the late nineteenth century, the latter was held to be endangered. It was only after 1945 that ethnology, now shorn of its colonial field, turned to studying the Ainu in terms of their culture and societal structure, thus reasserting control over a field of study dominated by Westerners. But this was hampered by the loss of traditions in the wake of the long-lasting assimilation policy. As Noemi Godefroy observes:

In 1937, [...] in the eye [sic] of the Japanese government, the Ainu have been [sic] completely assimilated and have, in fact, vanished as a people. This line of thought will be [sic] perpetuated by the [sic] successive governments for the next six decades36.

After the war, the theory of an ethnically homogenous Japan met with much success. Although critiqued since the 1990s, this myth is still very widespread37. It is a postulate of discourse about Japanese specificity which emerged in the 1970s, the same decade the Ainu started to voice identity demands and campaign for equal rights. This was the context in which the Minpaku devised the exhibition space devoted to Ainu culture. How was it possible to evacuate this burdensome history without triggering protests?

First presented in 1979 alongside the cultures of eastern Siberia, with which it shares many similarities, Ainu culture was presented autonomously in 1982, between eastern Siberia and the final space in the permanent exhibition devoted to Japanese culture. The Ainu display was divided into two large sections, one about daily life, and the other about beliefs. The first section had a model of an Ainu village and a reconstruction of part of the interior of a traditional house (chise), together with costumes, adornments, tools, and ceramics. The second section focused on celebrations for the ritual sacrifice of a bear (iomante), representative of the Ainu’s worship of this animal, with no reference to shamanism (already on display in far eastern Siberia).

on the left: tools for the nutritious activities of the Ainus, Minpaku (june 2011)

on the right: layout of an Ainu's traditionnal house (chise) and its surroundings (2011)

The purpose of these exhibits was to show the extent to which Japanese and Ainu culture had followed separate routes. For example, Japanese agricultural culture (mainly represented by rice farming) contrasted with Ainu subsistence livelihoods (hunting and fishing) which were closer to the practices of Siberian peoples. Equally, the ceremony “to send back the spirit of the bear” stood in sharp contradistinction to the part on rites and other festivities in Japan. These museographic choices and the position of the exhibits (outside Japanese culture) show the Minpaku’s desire to recognize Ainu culture as a fully-fledged indigenous culture specific to Hokkaido, thereby positioning itself in opposition to the political discourse of the Japanese state and the myth of Japanese cultural and ethnic homogeneity. Ōtsuka Kazuyoshi – the head of the team behind the exhibition – summed up the Minpaku’s point of view as follows:

[...] it was decided to show Ainu culture as an independent ethnic culture and affirm the reality that Ainu culture might be decreasing, but that there were still speakers of the Ainu language, that the original heart of the culture was still beating, that its traditions were being maintained, and that a sizable number of people affirmed their ethnic identity as Ainu38.

It should be noted that the exhibition was conceived in cooperation with people involved in promoting Ainu culture, such as the Hokkaidô Utari Association (Hokkaidō Utari kyōkai), one of the largest and oldest associations, the commemorative museum of the development of Hokkaido (Hokkaidō kaitaku kinen-kan), and Kayano Shigeru (1926-2006), a charismatic figure in the Ainu rights movement39. The fact that their opinion was taken into account marks a notable change in practices for exhibiting the Other. Even though it was feared that the opening of the exhibition might be marred by incidents, particularly actions by the Ainu liberation league, it was in fact welcomed by the community of Ainu associations.

It was only at a later stage that the exhibition attracted criticism, mainly for its a-historical dimension which resulted in there being no mention of the history of relations between Imperial Japan and the Ainu40. Additionally, the emphasis placed on what differentiates Japanese culture from Ainu culture meant the present-day reality of Ainu life was left to one side, resulting in an essentializing exhibition. Visitors could legitimately wonder whether it was an extinct culture, or whether the Ainu still lived in this manner. The Minpaku has thus encountered the same flaws as Western ethnology institutions, as well as the same setbacks as these museums when they have endeavored to make room for “multiple voices” of indigenous peoples41.

The exhibition of an ethnology museum – and by extension its interpretation – is subject to the context of any given period. When the gallery opened at a time when Ainu demands were being voiced, it was a matter of recognizing the existence of Ainu culture as a culture in its own right, even though this vanished Ainu culture had repercussions for Japan’s cultural and ethnic homogeneity. The endeavor to recognize the Ainu took precedence over any form of postcolonial critique. But by the time the exhibition was criticized two decades later, the context had changed, and its interpretation was thus a matter of debate.

Since then the museum has renovated its entire permanent exhibition – an undertaking which was completed in 2017 after fifteen years of work. Greater stress is accorded to placing cultures in perspective with their contemporary situation. The dwindling of the myth of Japan’s ethnic homogeneity and the advent of a multicultural society (something the government still refuses to openly acknowledge) have transformed the ideological context once again. Far from questioning the utility of the museum, these renovations, together with a reorganization of its research departments, reassert the importance of associating museum activity with research activity. The museum now presents itself as a “contact zone” and “forum” – terms borrowed from James Clifford and Duncan Cameron respectively – and has to face the advent of multiculturalism. The new museography makes some steps in this direction. However, to meet this challenge, the museum will have to a adopt a clearer political stance, as it has done with regard to the Ainu, and confront Japan’s colonial past head-on.

Notes

1

Umesao Tadao (ed.), Hakubutsukan no shisō. Umesao Tadao taidanshū (Museum thought. Collection of interviews), Tokyo Heibonsha, 1989, p. 47-48.

2

Seiderer Anna, Une critique postcoloniale en acte : les musées d’ethnographie contemporains sous le prisme des études postcoloniales, Collections digitales: Documents de sciences humaines et sociales, p. 13.

3

Kreiner Joseph, “Nihon minzokugaku/bunka jinruigaku no rekishi” (History of the Japanese society of ethnology and the Japanese society of cultural anthropology), in K. Joseph (ed.), Nihon minzokugaku no genzai. 1980 nen-dai kara 90 nen-dai he, Tokyo, Shin.yōsha, 1996, p. 3.

4

Anthropology, translated as jinrui-gaku 人類学 (literally, the science of mankind/humanity) as it developed at the Imperial University in the late nineteenth century was initially close to archaeology and the natural sciences, although its field of research rapidly expanded to include the study of customs. The term ethnology, translated minzoku-gaku 民族学 (literally the science of ethnic groups) was taken up in the wake of Japanese imperial expansion into new lands on the continent. It should also be mentioned that, in parallel to this, ethno-folklore (minzoku-gaku 民俗学 in Japanese, literally the science of folklore/folklore studies) developed outside institutions, focusing on the ethnography of Japan. Kunik Damien, 2018. “Fédérer les folkloristes japonais: histoire de la Minkan denshō no kai” in Bérose - Encyclopédie internationale des histoires de l’anthropologie, 2018 [on line].

5

In 1899, the government of Taiwan had already provided a public center for studying and exhibiting Taiwan, but it was only in 1908 that it became a museum. Lee Wei-i, “Cent ans de musées à Taiwan, du colonialisme au nationalisme”, Transcontinentales, no 4, 2007 [on line].

6

Mori.izumi Kai, “Manshū kokuritsu chūō hakubutsukan no tenrankai” (Exhibitions at the national central museum of Manchukuo), Hakubutsukan zasshi, vol. 36, no 1, 2010, p. 110-122; Ōide Shōko, “Nihon no kyū shokuminchi ni okeru rekishi kōko-gaku kei hakubutsukan no motsu seijisei” (The politicization of history and archaeology museums in the former Japanese colonies), Tōyō bunka kenkyū, no 14, 2012, p. 1-28.

7

Nanta Arnaud, “L’Historiographie coloniale à Taiwan et en Corée du temps de l'empire japonais (1890-1940)”, Politika, 2018 [on line].

8

Berthon Alice, “Avant la naissance du Musée national d’ethnologie 国立民族学博物館 (Kokuritsu minzokugaku hakubutsukan) à Senri, Japon (années 1930-1974)”, in Bérose. Encyclopédie internationale des histoires de l’anthropologie [on line].

9

Berthon Alice, “L’Attic museum: naissance d’un musée d’ethnologie”, in Y. Cadot, D. Fujiwara, T. Ōta, R. Scoccimaro (eds.), L’Ère Taishō (1912-1926): genèse du Japon contemporain?, Arles, Éditions Philippe Picquier, 2015, p. 89-98 [on line].

10

Seki Hideo, Hakubutsukan no tanjō: Machida Hisanari to Tōkyō teishitsu hakubutsukan (Birth of a museum: Machida Hisanari and the museum of empire in Tokyo), Tokyo, Iwanami shoten, 2005.

11

The 1912 exhibition was entirely devoted to demonstrating the power of the Japanese Empire. Most of the objects came from territories under its control. The goal was to provide the nation with an account of new conquests and industrial progress in the colonies. Manufactured objects were on display, together with scale models of bridges and major engineering works, as were the customs of the various ethnic groups living in Imperial lands.

12

Takushoku 拓殖 literally means “clearing the land/farming new land". In this context, it thus has the same meaning as "colonial" since it designates these new places. The exact title of this event was the "commemorative colonial exhibition of the Meiji era” Meiji kinen takushoku hakurankai (the Meiji era ran from 1868 to 1912).

13

Kang Inhye, “Visual Technologies of Imperial Anthropology: Tsuboi Shōgorō and Multiethnic Japanese empire”, Positions, vol. 4, no 4, 2016, p. 761-787.

14

Yamaji Katsuhiko, “Takushoku hakurankai to “teikoku-hanzunai no shojinshu”“ (Colonial exhibitions and the "map of races of the Empire ”), Shakai gakubu kiyō, no 97, 2004, p. 25-40.

15

Nanta Arnaud, “Les expositions coloniales et la hiérarchie des peuples dans le Japon moderne”, Ebisu, no 37, 2007, p. 3-17; Nanta Arnaud , “De l’importance des savoirs coloniaux à l’ère des impérialismes”, Ebisu, no 37, 2007, p. 99-114.

16

Matsuda Kyōko, Teikoku no shisen: hakurankai to ibunka hyōshō (Through the Empire’s eyes: exhibitions and representation of foreign cultures), Tokyo, Yoshikawa kōbunkan, 2003, p.161. Tsuboi S. used photography for his field studies at a very early stage, at a time when this was far from current practice.

17

Bouquet Mary (ed.), Academic Anthropology and the Museum, New-York/Oxford, Berghahn Books, 2006 [1st edition: 2001].

18

Yoshida Kenji, “Tōhaku and Minpaku within the History of Modern Japanese Civilization: Museum Collections in Modern Japan”, Senri Ethnological Studies, no 54, 2001, p. 77-102.

19

It was thus not museums but research centers and institutes which were concerned by requests for restitution. Similar requests were also made to Western institutions. Oda Hiroshi, “Hito kara hone he: aru ainu no ikotsu no repatriation to sai-ningenka” (From man to bones: about requests for the “repatriation” of human remains by certain Ainu and the reconstitution process), Hoppō jinbun kenkyū (Journal of the Center for Northern Humanities), no 11, 2018, p. 73-94.

20

Nakao Katsumi, “Minzoku kenkyû-jo no soshiki to katsudô: sensô-chû no nihon minzokugaku” (Organization and activities of the Center for ethnological study: ethnology during the war), Minzokugaku kenkyû, vol. 62, no 1, 1997, p. 47-65.

21

Berthon Alice, “L’Attic museum: naissance d’un musée d’ethnologie”, in Y. Cadot, D. Fujiwara, T. Ōta, R. Scoccimaro (eds.), L’Ère Taishô (1912-1926): genèse du Japon contemporain?, Arles, Éditions Philippe Picquier, p. 89-98.

22

Nanta Arnaud, “Pour réintégrer le Japon au sein de l’histoire mondiale: histoire de la colonisation et guerres de mémoire”, Cipango, no 15, 2008, p. 35-64.

23

This event is related in the purportedly non-official history of the Minpaku: Sofue Takao, “Minpaku de no jūnen-kan: sōsetsu zengo no koto, sono ta” (My ten years at the Minpaku: about, before, and after its establishment, and other things), Minpaku tsūshin, no 24, 1984, p. 6.

24

See the work by Kaneko Atsushi (particularly Hakubutsukan no seiji-gaku (Museum policy), Tokyo, Seikyū-sha, 2001) and the journal he edited on Japanese Museum history (Hakubutsukan-shi kenkyū, Study of museum history).

25

An ongoing research project at the Minpaku examines the relations between ethnology and building the nation-state. The anthropologist Katsumi Naoko has published articles on ethnology during the colonial period, and the historian Tōru has notably published a history of the Japanese Empire and anthropologists: Tōru Sakano, Teikoku Nihon to jinruigakusha 1884-1952 (The Japanese Empire and anthropologists. 1884-1952), Tokyo, Keisō shobō, 2005.

26

[forthcoming], Berthon Alice, “Le musée national d’ethnologie au Japon: un musée disciplinaire encore d’actualité?”, Retour à l’objet: fin du musée disciplinaire, Éditions Peter Lang.

27

Kurokawa Kishō & Umesao Tadao, “Kaiyūshiki hakubutsukan no genri” (Principle of a circuit-type museum), in T. Umesao (ed.), Hakubutsukan no shisō: Umesao Tadao taidanshū (Museum thought. Collection of interviews), Tokyo, Heibonsha, 1989, p. 133-154.

28

Iwaki Harusada, “Dezaina kara mita minpaku no tenji gijutsu” (The Minpaku’s exhibition techniques as seen by a designer), Kokuritsu minzokugaku hakubutsukan chōsa hōkoku, no 3, 2000, p. 37.

29

Inui Susumu, “Kagami ni utsuru ningen no sugata: yōroppa no minzoku hakubutsukan wo mite” (The appearance of man in the reflection in a mirror: looking at European ethnology museums), Gakujutsu geppō, vol. 25, no 4, 1972, p. 250. The report on a 1971 visit mentions statistics about the Japanese population dating from before the war, and of Japan sometimes being treated exotically. Concerning the ethnology Museum in Sweden, the report notes: "what is displayed in the room on Japan are objects such as sabers, straw pelerines, and long pipes. I wonder how Swedes are able to learn anything about Japan using such documents." Ogyū Chikasato, “Yōroppa shokoku no hakubutsukan shisatsu (1)” (Observation of European museums. 1), Kokuritsu minzokugaku hakubutsukan kenkyū hōkoku, vol. 1, no 1, 1976, p. 177-178.; Ogyū Chikasato, “Yōroppa shokoku no hakubutsukan shisatsu (2)” (Observation of European museums. 2), Kokuritsu minzokugaku hakubutsukan kenkyū hōkoku, vol. 1, no 3, 1976, p. 657.

30

On this subject, see Pigeot Jacqueline, “Les Japonais peints par eux-mêmes. Esquisse d’un autoportrait”, Le Débat, no 23, 1983, p. 19-33; Guthmann Thierry, “L’influence de la pensée Nihonjin-ron sur l’identité japonaise contemporaine: des prophéties qui se seraient réalisées d’elles-mêmes?”, Ebisu, no 43, 2010, p. 5-28.

31

Goodman Roger, “Making Majority Culture”, in J. Robertson (ed.), A Companion to the Anthropology of Japan, Oxford, Blackwell, 2005, p. 69.

32

Desveaux Emmanuel, “Le musée du quai Branly au miroir de ses prédécesseurs”, Ethnologies, vol. 24, no 2, 2002, p. 222. For other references to the museography of the Musée de l’Homme used here, see L’Estoile Benoit de, Le Goût des Autres. De l’Exposition coloniale aux Arts premiers, Paris, Flammarion, 2007 (particularly chapter V: “Des mondes sous vitrines : voyage au Trocadéro”, p. 175-204); Dubuc Élise, “Le futur antérieur du Musée de l'Homme”, Gradhiva, no 24, 1998, p. 71-91.

33

Umesao Tadao, Hakubutsukan no shisō: Umesao Tadao taidanshū (Museum thought. Collection of interviews), Tokyo, Heibonsha, 1989, p. 47-48.

34

Kinase Takashi, “Hyōshō to seijusei – Ainu wo meguru bunka jinruigaku-teki gensetsu ni kansuru sobyō” (Policy and representation. Outlines of anthropological discourse on the Ainu), Minzokugaku kenkyū, vol. 62, no 1, 1997, p. 1-21.

35

Nanta Arnaud, “Koropokgrus, Aïnous, Japonais, aux origines du peuplement de l'archipel. Débats chez les anthropologues, 1884-1913”, Ebisu, no 30, 2003, p. 123-154.

36

Noémi Godefroy, “Deconstructing and reconstructing Ainu identity. From assimilation to recognition 1868-2008”, 2001, p. 7 [on line].

37

Oguma Eiji, Tan.itsu minzoku shinwa no kigen (The origin of the myth of the homogenous nation), Tokyo, Shin.yōsha, 1995.

38

Ōtsuka Kazuyoshi, “A Reply to Sandra A. Niessen”, Museum Anthropology, vol. 20, no 3, 1997, p. 109.

39

Majima Chikako, Kayano Shigeru et la transmission de la culture aïnoue, INALCO, 2015 [Masters dissertation supervised by François Macé].

40

Niessen Sandra, “The Ainu in Mimpaku: A Representation of Japan’s Indigenous People at the National Museum of Ethnology”, Museum Anthropology, vol. 18, no 3, 1994, p. 18-25.

41

Dubuc Élise, Turgeon Laurier, “Musées et premières nations: la trace du passé, l’empreinte du futur”, Anthropologie et Sociétés, vol. 28, no 2, 2004,

Bibliographie

Alice Berthon, « Avant la naissance du Musée national d’ethnologie 国立民族学博物館 (Kokuritsu minzokugaku hakubutsukan) à Senri, Japon (années 1930-1974) » in Bérose - Encyclopédie internationale des histoires de l’anthropologie, 2018, (http://www.berose.fr/?Avant-la-naissance-du-Musee-national-d-ethnologie-国立民族学博物館).

Alice Berthon, « L’Attic museum : naissance d’un musée d’ethnologie », in Y. Cadot, D. Fujiwara, T. Ōta, Rémi Scoccimaro (dir.), L’Ère Taishō (1912-1926) : genèse du Japon contemporain ?, Arles, Éditions Philippe Picquier, 2015, p. 89-98 (http://sfej.asso.fr/spip.php?article116).

Alice Berthon, « Le musée national d’ethnologie au Japon : un musée disciplinaire encore d’actualité ? », in D. Antille (dir.), Retour à l’objet : fin du musée disciplinaire, Éditions Peter Lang, à paraître.

Mary Bouquet (dir.), Academic Anthropology and the Museum, New-York/Oxford, Berghahn Books, 2006 [1ère éd. : 2001].

Emmanuel Desveaux, « Le musée du quai Branly au miroir de ses prédécesseurs », Ethnologies, vol. 24, no 2, 2002, p. 219-227.

Élise Dubuc, « Le futur antérieur du Musée de l’Homme », Gradhiva, no 24, 1998, p. 71-91.

Élise Dubuc, Laurier Turgeon, « Musées et premières nations : la trace du passé, l’empreinte du futur », Anthropologie et Sociétés, vol. 28, no 2, 2004, p. 7-18.

Noémi Godefroy, « Deconstructing and reconstructing Ainu identity. From assimilation to recognition 1868-2008 », 2011, p. 7 (http://www.popjap.fr/blog/wpcontent/uploads/2013/03/Deconstructing_and_Recon structing_Ainu_identity_Popjap.pdf.)

Roger Goodman, « Making Majority Culture », in J. Robertson (dir.), A Companion to the Anthropology of Japan, Oxford, Blackwell, 2005, p. 59-72.

Thierry Guthmann, « L’influence de la pensée Nihonjin-ron sur l’identité japonaise contemporaine : des prophéties qui se seraient réalisées d’elles-mêmes ? », Ebisu, no 43, 2010, p. 5-28.

Harusada Iwaki, « Dezaina- kara mita minpaku no tenji gijutsu » (Les techniques d’exposition du Minpaku vues par un designer), Kokuritsu minzokugaku hakubutsukan chōsa hōkoku, no 3, 2000, p. 29-55.

Susumu Inui, « Kagami ni utsuru ningen no sugata : yōroppa no minzoku hakubutsukan wo mite » (L’apparence de l’Homme dans le reflet d’un miroir : en regardant les musées d’ethnologie européens), Gakujutsu geppō, vol. 25, no 4, 1972, p. 30-48.

Atsushi Kaneko, Hakubutsukan no seiji-gaku (La politique des musées), Tôkyô, Seikyū-sha, 2001.

Inhye Kang, « Visual Technologies of Imperial Anthropology : Tsuboi Shōgorō and Multiethnic Japanese empire », Positions, vol. 4, no 4, 2016, p. 761-787.

Takashi Kinase, « Hyōshō to seijisei – Ainu wo meguru bunka jinruigaku-teki gensetsu ni kansuru sobyō » (Politique et representation. Esquisse des discours anthropologiques sur les Aïnous), Minzokugaku kenkyū, vol. 62, no 1, 1997, p. 1-21.

Joseph Kreiner, « Nihon minzokugaku/bunka jinruigaku no rekishi » (L’histoire de la Société japonaise d’ethnologie et de la Société d’étude d’anthropologie culturelle), in J. Kreiner (dir.), Nihon minzokugaku no genzai : 1980 nen-dai kara 90 nen-dai he, Tokyo, Shin.yōsha, 1996, p. 3-8.

Damien Kunik, « Fédérer les folkloristes japonais : histoire de la Minkan denshō no kai », Bérose - Encyclopédie internationale des histoires de l’anthropologie, 2018 (http://www.berose.fr/?Federer-les-folkloristes-japonais-histoire-de-la-Minkan-densh%C5%8D-no-kai).

Kishō Kurokawa, Tadao Umesao, « Kaiyūshiki hakubutsukan no genri » (Principe d’un musée de type parcours), in T. Umesao (dir.), Hakubutsukan no shisō : Umesao Tadao taidanshū (La Pensée des musées. Recueils d’entretiens), Tokyo, Heibonsha, 1989, p. 133-154.

Benoit de L’Estoile, Le goût des Autres. De l’Exposition coloniale aux Arts premiers, Paris, Flammarion, 2007.

Chikako Majima, Kayano Shigeru et la transmission de la culture aïnoue, mémoire de Master 2 dirigé par François Macé, INALCO, 2015.

Kyōko Matsuda, Teikoku no shisen : hakurankai to ibunka hyōshō (Le regard de l’empire : les expositions et la représentation des cultures étrangères), Tokyo, Yoshikawa kōbunkan, 2003.

Kai Moriizumi, « Manshū kokuritsu chūō hakubutsukan no tenrankai » (Les expositions du musée national central de Mandchoukouo), Hakubutsukan zasshi, vol. 36, no 1, 2010, p. 110-122.

Katsumi Nakao, « Minzoku kenkyū-jo no soshiki to katsudō : sensō-chū no nihon minzokugaku » (Organisation et activités du Centre d’étude ethnologique : l’ethnologie pendant la guerre), Minzokugaku kenkyû, vol. 62, no 1, 1997, p. 47-65.

Arnaud Nanta, « Koropokgrus, Aïnous, Japonais, aux origines du peuplement de l'archipel. Débats chez les anthropologues, 1884-1913 », Ebisu, no 30, 2003, p. 123-154.

Arnaud Nanta, « Les expositions coloniales et la hiérarchie des peuples dans le Japon moderne », Ebisu, no 37, 2007, p. 3-17.

Arnaud Nanta, « De l’importance des savoirs coloniaux à l’ère des impérialismes », Ebisu, no 37, 2007, p. 99-114.

Arnaud Nanta, « Pour réintégrer le Japon au sein de l’histoire mondiale : histoire de la colonisation et guerres de mémoire », Cipango, no 15, 2008, p. 35-64.

Arnaud Nanta, « L’Historiographie coloniale à Taiwan et en Corée du temps de l’empire japonais (1890-1940) », Politika, 2018 [https://www.politika.io/fr/notice/lhistoriographie-coloniale-a-taiwan-coree-du-temps-lempire-japonais-18901940-ii].

Sandra Niessen, « The Ainu in Mimpaku: A Representation of Japan’s Indigenous People at the National Museum of Ethnology », Museum Anthropology, vol. 18, no 3, 1994, p. 18-25.

Hiroshi Oda, « Hito kara hone he : aru ainu no ikotsu no repatriation to sai-ningenka » (De l’homme aux os : à propos des demandes de “repatriation” des restes humains de certains Aïnous et le processus de reconstitution), Hoppō jinbun kenkyū (Journal of the Center for Northen Humanities), no 11, 2018, p. 73-94.

Eiji Oguma, Tan.itsu minzoku shinwa no kigen (L’origine du mythe de la nation homogène), Tokyo, Shin.yōsha, 1995.

Chikasato Ogyū, « Yōroppa shokoku no hakubutsukan shisatsu (1) » (Observation des musées européens. 1), Kokuritsu minzokugaku hakubutsukan kenkyū hōkoku, vol. 1, no 1, 1976, p. 177-178.

Chikasato Ogyū, « Yōroppa shokoku no hakubutsukan shisatsu (2) » (Observation des musées européens. 2), Kokuritsu minzokugaku hakubutsukan kenkyū hōkoku, vol. 1, no 3, 1976, p. 657-659.

Shōko Ōide, « Nihon no kyū shokuminchi ni okeru rekishi kōkogaku kei hakubutsukan no motsu seijisei » (La politisation des musées d’histoire et d’archéologie dans les anciennes colonies japonaises), Tōyō bunka kenkyū, no 14, 2012, p 1-28.

Kazuyoshi Ōtsuka, « A Reply to Sandra A. Niessen », Museum Anthropology, vol. 20, no 3, 1997, p. 108-119.

Jacqueline Pigeot, « Les Japonais peints par eux-mêmes. Esquisse d’un autoportrait », Le Débat, no 23, 1983, p. 19-33.

Tōru Sakano, Teikoku Nihon to jinruigakusha 1884-1952 (L’empire japonais et les anthropologues : 1884-1952), Tokyo, Keisō shobō, 2005.

Anna Seiderer, Une critique postcoloniale en acte : les musées d’ethnographie contemporains sous le prisme des études postcoloniales, Collections digitales : Documents de sciences humaines et sociales (https://www.africamuseum.be/docs/research/publications/rmca/online/documents-social-sciences-humanities/critique-postcoloniale.pdf).

Hideo Seki, Hakubutsukan no tanjō: Machida Hisanari to Tōkyō teishitsu hakubutsukan (Naissance du musée : Machida Hisanari et le musée de l'empire à Tōkyō), Tokyo, Iwanami shoten, 2005.

Takao Sofue, « Minpaku de no jūnen-kan : sōsetsu zengo no koto, sono ta » (Mes dix années au Minpaku : à propos de l’avant et de l’après de son établissement, et d’autres choses), Minpaku tsūshin, no 24, 1984, p. 2-10.

Sakano Tōru, Teikoku Nihon to jinruigakusha 1884-1952 (L’empire japonais et les anthropologues. 1884-1952), Tokyo, Keisō shobō, 2005.

Tadao Umesao (dir.), Hakubutsukan no shisō : Umesao Tadao taidanshū (La Pensée des musées. Recueils d’entretiens), Tokyo Heibonsha, 1989.

Lee Wei-i, « Cent ans de musées à Taiwan, du colonialisme au nationalisme », Transcontinentales, no 4, 2007, p. 1-24 (http://transcontinentales.revues.org/668).

Katsuhiko Yamaji, « Takushoku hakurankai to “teikoku-hanzunai no shojinshu” » (Les expositions coloniales et la « carte des races de l’Empire »), Shakai gakubu kiyō, no 97, 2004, p. 25-40.

Kenji Yoshida, « Tōhaku and Minpaku within the History of Modern Japanese Civilization : Museum Collections in Modern Japan », Senri Ethnological Studies, no 54, 2001, p. 77-102.