Mabogo P. More

Mabogo P. More is an Azanian (Black and Indigenous) Africana existential philosopher. Born in 1946 in Benoni, east of Johannesburg, he is one of South Africa’s great living philosophers. Despite what he referred to as philosophy’s “viciously hostile atmosphere” for Black people, More was one of the few Black professors of philosophy during apartheid in South Africa. He completed his BA and Honors at the University of the North, where Cyril Ramaphosa and Chabani Noel Manganyi also studied. While more than half of the white lecturers there at the time were both incompetent and Secret Security agents, the Black Consciousness Movement held its first national conference on the campus during More’s first year of study and, in his final year, a fellow student established a local branch of the South African Student Organisation (SASO) there. More would also study at Indiana University in Bloomington, Birmingham University in England, the University of Illinois, Chicago Circle, and Harvard University, before earning his PhD from University of South Africa (UNISA) in 2005. At the time of obtaining his degree, he had published more than twenty journal articles and book chapters on African philosophy and racism. More taught philosophy at University of Limpopo, University of Cape Town, University of Durban Westville, and University of KwaZulu Natal. In retirement, he has published four books, Biko: Philosophy, Identity and Liberation (2017), Looking through Philosophy in Black: Memoirs (2019), Sartre on Contingency: Antiblack Racism and Embodiment (2021), and Noel Chabani Manganyi: Being-While-Black-and-Alienated in Apartheid South Africa (2024). In 2015, More received the Frantz Fanon Lifetime Achievement Award from the Caribbean Philosophical Association. In South Africa, he has faced a polarized reception: on the one hand, decades of professional recognition denied, on the other, consistent and clear evidence of the hunger of youth, students, and activists for philosophical work like his.

Jane Anna Gordon (JAG) – You describe Azania – the name chosen by the Pan-African Congress and the Black Consciousness Movement to replace the colonial name of South Africa “as the rightful name of a political horizon for true independence.”1 It gestures well beyond “pseudo-independence,” “flag independence,” or what you call “post-apartheid apartheid.”2 You write, “The land issue for the poor is one of the main issues that has preoccupied my intellectual work.”3 What are the conditions of possibility for steadily approaching the Azanian horizon? What is entailed in reopening the aim of reappropriating land, of closing the gap between possessing a right to own land and being Black, of having a relation to the land itself without the mediation of predominantly white land, capital, and resources (the Bill of Rights of an otherwise pathbreaking South African Constitution guaranteed 87% of the land to whites, land that was originally stolen by white colonialists from Black people)?

Mabogo Percy More (MPM) – Yes, it is correct that the name Azania was chosen by the Pan-African Congress (PAC) and later adopted by the Black Consciousness Movement as the legitimate and original name of the country now called “South Africa,” which was created by English and Dutch settlers in 1910 as the Union of South Africa without and against the native Black peoples of the territory. For the PAC, Azania represented an idea and a vision of an African state that is completely liberated from the vestiges of colonial hegemony, be it political, economic, social, cultural, and ideologies of domination. Such a polity would then rejoin and become a part of the entire African community of states. The name “South Africa,” for the Azanians, is a colonial designation that represents a historical trajectory of the dispossession, oppression, exploitation, and dehumanization of Black people. Besides being a colonial name, it is, by virtue of its coloniality, as the late jazz musician Zim Ngqawana’s titled track “Sad Afrika (A Country Without a Name)” in his CD Zimphonic Suites indicates,4 a colonial geographical reference and not even a proper name. Preserving this colonial geographical reference is indicative of its enduring colonial baggage. Unlike Zimbabwe (formerly Rhodesia), Malawi (formerly Northern Rhodesia), both named after Cecil John Rhodes, Ghana (formerly Gold Coast), or Zambia (formerly Nyasaland), South Africa remains a colonial enclave in which the land is still in the hands of the colonial settlers in accordance with the Native Land Acts of 1913 and 1936, which ultimately limited African land ownership to thirteen percent of the entire country’s landscape.

By Azania I mean the emergence of a polity completely decolonized and free from its colonial baggage. Since colonialism, especially settler colonialism, is first and foremost the seizure of the land of the native population, the name Azania is therefore fundamentally connected to land dispossession. Let me say that the struggle against colonialism throughout the world has hitherto been the fight for land repossession. The struggles of the Native Americans in the USA, the Mȃori people of New Zealand, the Australian Aborigines, the Mapuche in Southern Chile, the Eskimos of Arctic Canada, and Africans in Africa have all been struggles against land expropriation by the colonizers. While the focus of the new activism for reparations such as the National Coalition of Blacks for Reparations in America (N’COBRA) and the Africa Reparation Movement (ARM) has been on economic reparations (cancellation of the external debt of Third World countries, the return of stolen art objects to their home countries, etc.), the land question has not been abandoned. Indeed, the hottest issue in the Southern African region today is still the Zimbabwean and “South Africa” land question. The region’s political leaders are caught between the legitimate demands of the land by hungry Black African masses and the minority white farmers’ occupation of the land.

The importance of the land for continued existence and survival cannot be overstated. It is a matter of life and death as the over forty thousand plus Palestinians body bags count indicates today. Israeli settlers, for example, are expropriating land occupied by the Palestinians in the West Bank. As Fanon correctly pointed out, “For a colonized people, the most essential value, because the most concrete, is first and foremost the land; the land which will bring them bread and above all, dignity.”5 Taking the land away from someone is essentially taking away their life; and this is an act of pure and absolute violence. So, Azania, as I have argued in my contribution to Living Fanon in 20116 and other writings, would be a completely liberated zone, not an abstract freedom or “pseudo-independence” that offers only a new flag (flag freedom) but genuine freedom that would bring an equitable distribution and restoration of the land to the rightful owners. Flag independence was expressed through what is, even today, absurdly glorified to be the most progressive Constitution. It is this very “progressive” Constitution that guaranteed the former colonizers 87% of the land and only 13% to the African people. Strictly speaking, the land was not a priority of the ruling African National Congress (ANC) from its inception in 1912. So, the Convention for a Democratic South Africa (CODESA) settlement in 1991-1992 was simply an exchange of land rights for political power. From the settlement, the land stolen from the African people would not be returned.

The Economic Freedom Front (EFF) led by Julius Malema with its land expropriation without compensation demand has proverbially put the cat among the pigeons. As a result, the land issue has gained momentum among landless poor Black communities, civil movements and organizations such as Black First Land First, Landless People’s Movement, Abahlali baseMjondolo, or Anti-Eviction Campaign Movement, etc. Disgruntled with the ANC’s failure to deal effectively with landlessness, members of these movements and organizations have proclaimed: “No Land, No Vote.” Indeed, the recent failure by the ruling ANC to obtain a majority vote during the 2024 general elections indicates this disgruntlement and dissatisfaction about their handling of the land issue.

What are the possibilities and limits of achieving genuine independence through land restitution? Indeed, Black people are aware that the possibility of realizing Azania is marked by a number of obstacles which require serious attention. It will be naïve, for example, to think that the land issue will be resolved in our favor in my life-time precisely because there are numerous hostile opposing players involved in South African land as it was for Zimbabwe as well. We are aware that our struggle for land is not only against South African whites who own 87% of the total landscape, but also against the former colonial masters, the USA, United Kingdom, European countries such as the Netherlands, France, etc., multinational corporations, the World Bank, the IMF, and Western conglomerates, growing right-wing groups and governments, and white capitalist individuals’ economic interest. We have learned from the Zimbabwe experience of land expropriation without compensation that the wrath of the white Western world, the center of power, will descend upon us with a heavy vengeance and a heavy price to pay. White reactions to the EFF’s expropriation without compensation cry and its demand for the amendment of Clause 25 of the Constitution, predictably and unsurprisingly caused the local currency (the Rand) to immediately weaken as the Zimbabwe Dollar did when President Mugabe appropriated land from the white colonial settlers. We now get statements such as “The protection of property rights is fundamental to sound economics” or “The proposed amendment is the removal of a fundamental human right essential for democracy” or the historically problematic claim that the original owners of the land are the San and the Khoikhoi people, that Black Africans migrated to the tip of Africa from up north. What we have to realize is that reappropriating the land will come through heavy struggles, that it will not be easy, and that the odds are stacked against us. But this does not mean sinking into despair. On the contrary, it means being prepared and ready to encounter resistance, to take the responsibility for our actions (struggles) and to believe that sooner or later an equitable distribution of land will occur through our efforts. As Biko – in the same tone as Frederick Douglass – warned, the system concedes nothing without demand. Unlike some colonial enclaves (e.g., USA, Australia, and New Zealand) where genocide was carried out against the native population, we in this country have our hopes in the advantage of numbers.

In order to hold on to political power, the ANC, in the name of Government of National Unity (GNU) has recently – I suspect with the command from the World Bank – handed over the portfolio of the Ministry of Agriculture, Land Reform, and Rural Development to the leader of the mainly white Democratic Alliance, Mr. John Steenhuisen, whose party serves the interests of white monopoly capital and is vehemently opposed to land distribution. That appointment brings the land issue to an abrupt halt. In Zimbabwe, Western sanctions have coerced the government to consent to reimbursing the former white owners of farms for the land appropriated by President Mugabe in accordance with the Lancaster agreement of the willing seller and a willing buyer principle.

As long as the land issue is not resolved, white South Africans will never find peace. Sooner or later this struggle for land will take a different path, comparable or even worse than the Gaza massacre. I think that the measurement of real transformation in this country from its colonial and apartheid past to a truly democratic dispensation will depend directly on the extent to which land redistribution to Blacks is accomplished. Karl Marx asserted that the history of all hitherto existing societies is the history of class struggle. In the same manner, I contend that the history of all hitherto colonial societies is the history of the land struggle. The tragedy of Gaza is a clear reminder that as long as the land question is not resolved, there will be violent struggle for land redistribution.

JAG – In Memoirs,7 you describe how, before sitting down to write or before going to sleep, you would listen to the music of Curtis Mayfield, Bob Marley, Fela Anikulapo Kuti, Gil Scott Heron, and Aretha Franklin. This music “taught Black people how to make a difference.”8 You emphasize the singular writing in the liner notes of their albums, its lucidity, creativity, and rhythm, and how it put one in the right frame of mind to listen and to hear. How did this mode of writing inform how you composed your own philosophical works and how you prepared your students to hear what various philosophical voices had to say?

MPM – Philosophy is a situated activity; it does not appear from nowhere, ex nihilo. It emerges from an existential situation or social milieu in which an existential reality or social contention is inevitably entrenched. Philosophers are situated human beings whose philosophical contributions are grounded in their lived-experiences or situations. Thrown and situated within an oppressive apartheid situation, I immediately became very passionate about questions relating to racial identity and the differences among the lived-experiences of Whites, Indians, Coloureds, and Africans and this passion continues to stimulate and energize my philosophical work today.

As an Africana existentialist, I believe that philosophy must therefore begin from the subjective experience because the self and its anguish, happiness, anger, anxiety, suffering, and more cannot be apprehended through detached contemplation, but must be inwardly appropriated. In point of fact, for existentialists in general, philosophy is not simply an intellectual pursuit but a mode of being, an involvement with the realities of lived experience. Consequently, a human being is not simply a rational being, but also a passionate and spiritual being. Put differently, philosophy for existentialists is not abstract self-reflection or aloof meditation alone, but also a complete emotional involvement in the drama of existence. This conception of the world applies directly to jazz music – and maybe music as a whole – because jazz, for me, is a personal, passionate, and subjective musical interpretation of the world.

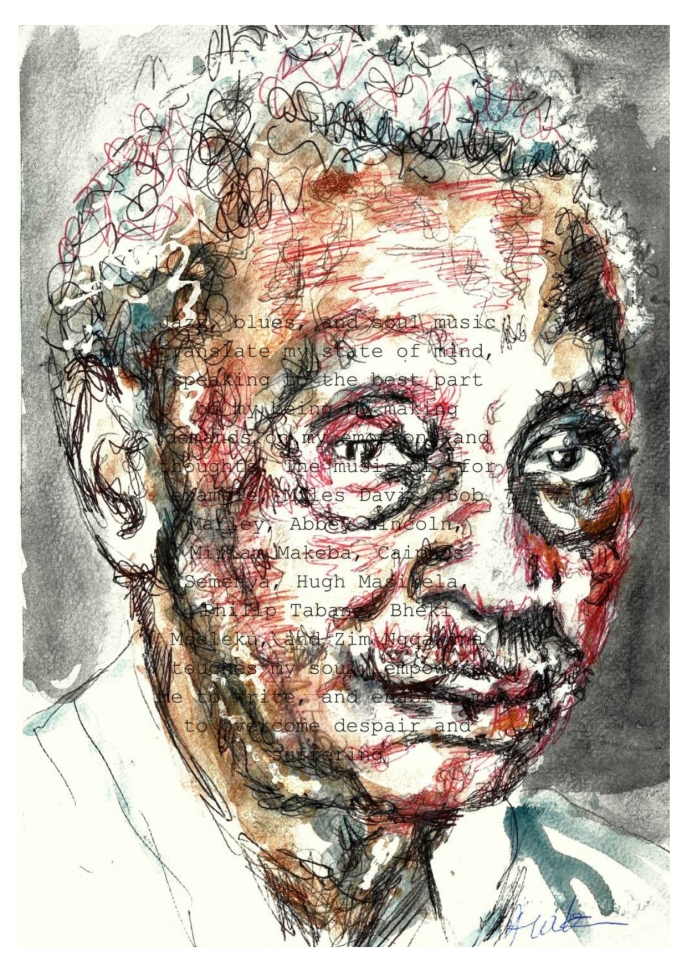

Jazz, blues, and soul music translate my state of mind, speaking to the best part of my being by making demands on my emotions and thoughts. The music of, for example, Miles Davis, Bob Marley, Abbey Lincoln, Miriam Makeba, Caiphus Semenya, Hugh Masikela, Philip Tabane, Bheki Mseleku, and Zim Ngqawana touches my soul, empowers me to write, and enables me to overcome despair and suffering. It often also brings about joy and happiness in the face of tremendous and unspeakable hardship and suffering. In a nutshell, music forces me to confront the fundamental philosophical issue of what it means to be human. It pushes me to the realization that the philosophical separation of emotion and reason is questionable and unconvincing.

As I mentioned elsewhere, I would not say that I consciously use jazz music as a mode of writing to articulate my philosophical work. Some Black philosophers who are also musicians, philosophers such as Lewis Gordon or Tommy Lott, might have transferred their musical sensibilities and rhythms directly into their writing. I cannot say that I was or am in that league. However, because I often think with my ears, I have always been moved by socially and politically radical music. The strong political and social messages in the music of Curtis Mayfield, Bob Marley, Fela Kuti, Gil Scott-Heron, Aretha Franklin, Abbey Lincoln, and Max Roach resonated with my situation as an oppressed Black subject. Such music spoke to the best part of my being. For example, when in his “Redemption Song” Bob Marley sings: “Emancipate yourselves from mental slavery, none but ourselves can free our minds […]. How long shall they kill our prophets, while we stand aside and look?”9 I hear the call of Stokely Carmichael (Kwame Ture), Steve Biko, W.E.B. Du Bois, Frantz Fanon, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, and many others imploring me and other Black folks to emancipate and decolonize our minds. When in Drums Unlimited Max Roach’s drums begin to sound like machine guns that killed Black people organized by the Pan-African Congress in Sharpville in 1960 protesting against the pass laws, and when Curtis Mayfield says “We People Who Are Darker than Blue,”10 I am inspired to keep on the struggle for justice in my writings precisely because of my facticity as “darker than blue,” a color that inevitably and spontaneously constituted me as a victim of the pass laws during the apartheid era.

It was not only the music per se that inspired my writing, but the lyrics that drew my attention to the political, social, and economic sufferings of Blacks. They brought to my attention the fact that the struggles of Black people around the world, though different in some ways, were fundamentally the same in many respects. The Black Consciousness Movement connected music and speeches. Curtis Mayfield’s songs, such as “If there’s a Hell Below We’re All Going to Go” or “We’re a Winner,” Aretha Franklin’s “Respect” and “A Change is Gonna Come,” Bob Marley’s “Crazy Boldheads,” “War,” or “Redemption Song,” Fela Kuti’s “Zombie,” “ITT,” “Sorrow Tears and Blood,” Gil Scott-Heron’s “The Revolution Will Not Be Televised” and “Johannesburg,” Hugh Masekela’s “Stimela,” and Harry Belafonte and Miriam Makeba’s album, An Evening With Belafonte/Makeba, especially the track “Maba Yeke” (“Hands Off Our Land”), which is about colonial land theft, all stimulated a self-consciousness that I would probably not have acquired had I not listened to some of these songs early in my life. Such lyrics raised my consciousness about my apartheid situation. My political consciousness was also raised by African-American political speeches. Actually, I had long playing (LP) vinyl records of the speeches of Malcolm X, Stokely Carmichael, and Dick Gregory.

There is much in common between jazz and blues and existentialism and, as a jazz and blues lover, existentialism became a natural philosophical home for me. For instance, both Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir frequented jazz clubs and listened to the music with a sensitivity to its inner emotional meaning. They loved jazz and appropriated and used it in their works because, for both of them, jazz was associated with the fundamental existentialist ontological category of human reality: freedom. But, as Colin W. Nettelbec observes, where Sartre used jazz to inform and illustrate his philosophy, Beauvoir derived from it a programme of action.

Sartre refined his understanding of jazz into numerous existentialist critical qualities: spontaneity, perpetual originality and self-renewal, and the capacity to unite musician, instrument, and music into a single future-oriented act. He considered jazz a form of emotional release of freedom. For him, jazz fostered openness and this made change possible. In effect, Sartre—even Beauvoir—fused jazz and existentialism to articulate important and crucial aspects of his philosophy. He saw jazz as the musical manifestation of the existentialist freedom he described in his philosophical texts. Like Sartre’s protagonist, Antoine Roquentin in the novel Nausea, I tended to assuage the terror of my existential nausea brought about by the contingency and meaninglessness of my existence as a Black individual in an antiblack apartheid world by listening to jazz, particularly the blues.11

As a thoroughly colonized African, taught to valorize the English language and forced to internalize the lies that one is more human in proportion to one’s ability to speak and be proficient in English, I marveled at the creative and rhythmic manner in which jazz critics, especially, wrote their liner notes on the back covers of LPs. My favorite jazz critics were Leonard Feather, Nat Hentoff, and Ralph J. Gleason. For example, on Miles Davis’s Bitches Brew, Gleason beautifully wrote about the music: “And sometimes I think maybe what we need is to tell people that this is here because somehow in this plasticized world they have the automatic reflex that if something is labelled one way, then that is all there is in it and we are always finding out to our surprise that there is more to Blake or more to Ginsberg or more to ‘trane or more to Stravinsky than whatever it was we thought was there in the first place.”12

Since radical African music (e.g. Harry Belafonte and Miriam Makeba’s An Evening with Belafonte/Makeba (1965)) was banned by the apartheid Censorship Board, we were invariably drawn to radical African-American music. Radical jazz albums and songs with titles such as Max Roach’s “The Freedom Now Suite” and “Sharpeville,” Gil Scott-Heron’s “From South Carolina to South Africa,” “The Revolution Won’t Be Televised,” and “Johannesburg,” Billie Holiday’s “Strange Fruit,” Cannonball Adderley’s “Mercy, Mercy, Mercy!!” “Work Song,” or “Country Preacher,” Louis (Satchmo) Armstrong’s “That Lucky Old Sun,” Miles Davis’s “Mr. Freedom X,” Abbey Lincoln’s “Driva’ Man,” “Mendacity,” and so on, not only inspired us, but also gave us hope that one day, things will turn around for us, that, as Max Roach wrote, there would be “Freedom Now.”13

Besides jazz, other genres also attracted the attention of politically conscious South African urban Blacks, for example, soul music in James Brown’s revolutionary “Say It Loud, I’m Black and I’m Proud,” or Nina Simone’s “Young, Gifted and Black.” I personally liked the music of Curtis Mayfield with its radical lyrics, such as in the albums There’s No Place Like America Today and Curtis Mayfield Live, the social statements in Marvin Gaye’s songs, and, of course, the inimitable Bob Marley. Who, as a politically conscious Black person, could forget Bob Marley’s song, “War,” with the message that conflict is inevitable where racism reigns supreme? The rebellious spirit and music of Fela Anikulapo Kuti also had a profound influence on me personally. Despite all these influences, jazz was and still is the dominant musical form that inspires my writings and life.

JAG – You were deeply inspired by Paulo Freire’s Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Although banned in apartheid South Africa, you regularly employed his “pedagogical methodology” in your teaching career in university classrooms and as an instructor at the Workers’ College in Durban and with NGOs and community organizations, such as the shack dwellers and rural projects. In addition to affirming how antipathetic the apartheid regime was to free thinking, what did your own pedagogical work suggest about who can engage in and grow through engagement with philosophical endeavor? Given the radical inequalities that continue to limit who can become a formal student, do you continue to consider philosophy, philosophical education, and philosophical writing as necessarily continuing in and beyond formal institutions of higher education?

MPM – Indeed, Paulo Freire’s critical pedagogy, with its existentialist flavor, was inspirational during my teaching career. His ideas remained with me throughout my university teaching career and also while working as an instructor at the Durban Workers’ College and a few NGOs. At the Workers’ College, this critical pedagogy assumed a fulfilling pedagogical practice given the wide practical experiences of the workers and the infusion of a radical consciousness about the contradictions of their situation as an oppressed and exploited group.

My introduction to Freire’s revolutionary pedagogy began when I saw and bought his seminal book, Pedagogy of the Oppressed,14 from a café which sold revolutionary books in downtown Johannesburg and which, for some unknown reason, evaded detection by the ubiquitous apartheid security police. The text forced a new vision on me. I came to think of education as a site of cultivating an overpowering reciprocity between learners and teachers. Because of my schooling and student experiences of teacher authoritarianism, Freire’s insights made me rethink the very idea of the relationship between the educator and the learner, even outside of the traditional banking system of education in which I was educated and socialized.

The traditional banking system, according to Freire, is one in which students are taught not to be active participants in the learning process, but are encouraged to be mere passive recipients and reproducers of information transmitted by the omniscient teacher. For Freire, education should be dialogical, should and ought to be dangerous, especially to those who require us not to ask disturbing questions about colonialism, capitalism, and racial, cultural, social, or gender oppression. Education, for Freire, should be about the transformation of our world.

I must point out, however, that many of my university students initially resisted the Freirean method of teaching. They were used to being spoon-fed and regurgitating exactly what they were taught. Naturally, one cannot blame them. They were required by their Afrikaans-speaking white lecturers—who were taught in Afrikaans and had problems with and hatred of English—to regurgitate verbatim their class dictated notes. Also, most African students—like myself during my student days—had problems articulating themselves in English, which is not our first language. The natural tendency was to resist active participation for fear of their English incompetency being exposed or making fools of themselves. In these cases, I would urge them to express themselves in their African or any other language. But they later came to appreciate the non-authoritarian spirit of the class and slowly became free to participate.

As a matter of fact, much of Freire’s thought was already appropriated by Biko and the South African Students’ Organisation (SASO) which birthed the Black Consciousness Movement in the country. It was from Freire that the ever-revolutionary notion of “Education for Liberation” and the transformative concept of conscientization were inherited and adopted. Freire’s concept of conscientizaҫȃo meant learning to perceive social, political, and economic contradictions and to take action against oppressive elements of reality. In short, conscientization, which operated as a leitmotif of my teaching project throughout my career, referred to the awakening of critical consciousness and of having critique to bear on every facet of Black lived experience. A key element in Freire’s ideas –which stayed in my mind – is the recognition that teaching should be a political act directly related to production, politics, and social conditions in order to prepare for a society still to be realized in the future.

I have always thought it necessary for students to develop an appreciation for the socio-historical situation in which they live or find themselves. Thus, for example, in my political philosophy class and at the Workers’ College and civil society organization seminars, Fanon’s chapter “The Pitfalls of National Consciousness” in the Wretched of the Earth15 served as a springboard for critiquing apartheid and “post-apartheid apartheid” South Africa. The fundamental project and aim of my pedagogical practices, therefore, was derived from Freire’s concept of conscientization, which was later adopted by the Black Consciousness Movement in its summer schools. The aim was to foster, restore, and reaffirm the political, social, and cultural dignity of Black people and their experiences through the cultivation of their self-consciousness.

Freire’s work emerged at a critical time of consciousness awakening in South Africa, a time when Black people were beginning to profoundly question the politics of domination and the logic of apartheid antiblackness. The leadership of the Black Consciousness Movement was thrilled by Freire’s method and requested Anne Hope, an expert who was conducting training courses on Freire’s pedagogical method in Johannesburg, to assist the movement. The lessons were used effectively by Black Consciousness members in the Black Community Programme in teaching literacy to the communities where they worked. I attended one of these sessions when I was a student doing my Honours degree and gained a lot of valuable insights into conducting lectures and seminars.

One important aspect of philosophy is that it cannot be confined to the academic sphere only. In other words, one need not have formal degrees in philosophy or become a formal student of philosophy at an academic institution for one to learn philosophy or benefit from it, or even be able to advance philosophical theories. For example, a lot of the dominant figures of Western philosophy did not have formal degrees in philosophy. Yet philosophical ideas and writings have transcended formal institution of education. A case in point is the Black Consciousness Movement in South Africa. When I published my first piece on Biko as an Africana philosopher,16 a reviewer objected that Biko did not study philosophy, that he was a medical student.17 Not only do you not need to have studied philosophy for you to be considered a philosopher, you don’t even need to have been at a university to be a philosopher. Odera Oruka in his Sage Philosophy has demonstrated that African sages were philosophers in the past. Marcel Griaule also articulated Ogotemmêli’s cosmology in his text Conversations with Ogotemmêli (1965). Indeed, Fanon’s philosophy has found a home among the shack dwellers’ movements such as Abahlali baseMjondolo and civil society movements such as Black First Land First and Landless People’s Movement. Many of the young Blacks who are not students or affiliated with an institution of higher education are eager and devoted readers of Fanon, my work, Tendayi Sithole, Chabani Manganyi, Lewis Gordon, Mogobe Ramose, and a host of other philosophical texts. For instance, at a certain period in my life, I had a close working relationship with the leader of Black First Land First, and a one-time executive member of the Economic Freedom Front (EFF), Andile Mngxitama. As the editor of a radical public journal, New Frank Talk: Critical Essays on the Black Condition, Mngxitama published my non-academic piece, “Psycho-Sexual Racism and the Myth of the Black Libido,” in the journal.18 In an attempt to reach a wider audience, I have over the years published articles in several national newspapers such as City Press (Johannesburg), The Sunday Times (Johannesburg), Mail & Guardian (Johannesburg), and The Mercury (Durban).

I should close by saying that through some of my work and that of other Black philosophers in this country, I have come to realize how hungry people – especially the youth, students, and activists – are for thoughtful texts, articles, and media commentaries on political, socio-economic, and cultural issues. The reception of my book on Steve Biko and the numerous academic journals and newspaper commentaries I and other philosophers, such as Dr. Sarh Setlaelo, have published indicated to me the magnitude of the need people outside the academies have for philosophical reflection on what they do and what happens to them. Philosophers, therefore, need the courage to leave the security, comfort, and cushion of the university and address non-academic people on issues affecting them, whether they be of individual, socio-political, economic, or even religious significance. “Each generation, as Fanon said, must […] discover its mission, fulfill it, or betray it.”19 In other words, every generation has its own responsibility and all we can do is not prescribe to them but make them aware of their responsibilities. We can only bring to their consciousness their situation and lived experiences.

JAG – You describe philosophy as “finding you and not letting you go.”20 At the same time, when writing your Memoirs, you describe yourself, in the face of the paucity of young Black women and men aspiring to become future philosophers, wondering if they could be persuaded to follow your path. In the face of countless denials – of mentors who were philosophers in their own right and who were not racists; of libraries with philosophical literature in your mother tongue; of the visibility of your life-world – love of philosophy offered resilience and purposefulness in the heart of an apartheid built on nihilism and oppression, it entailed the freedom of a rehumanizing self-definition. Can you say more about how your love of philosophy nurtured resilience, purposefulness, and self-definition in the face of immense odds and why these are values worthy of our embrace and affirmation?

MPM – As I narrated in my Memoirs,21 township wisdom (life) had taught me that anyone with bright, intelligent, and deep ideas was a psychologist, such that if anyone came up with a bright and tricky idea that confused the rest of us, we would then say: “He is using psychology on us.” On arrival at the University of the North (Turfloop), which, incidentally, was the first time I ever set foot on or had seen any university campus, I immediately registered for a BA degree, choosing Psychology and History as my majors. When I became a student at this Historically Black Institution, there was no orientation or career guidance programme. I included philosophy because it was in the curriculum and not because I knew what it was. I simply had no idea what philosophy was. Some of my African-American colleagues are able to say that they were drawn to philosophy at an early age in their lives – for example, Lewis R. Gordon, Michele M. Moody-Adams, Anita L. Allen, and George Yancy – but I cannot say that about myself.22

Frankly, I was looking for a subject that had something to do with lofty ideas, but I actually mistook psychology for philosophy. Prior to my university years, I came across a book by David Hume, Treatise on Human Nature, and John Locke’s Two Treatise on Civil Government at the local library in my former township that was rezoned an Indian Area when we were forcibly removed to another township twenty kilometers away from the white town. I tried reading Hume and Locke without realizing that I was reading philosophical texts. All I knew was that I was reading very interesting ideas about human beings, even though my understanding was negligeable. Psychology at the first-year level turned out to be an uninteresting study of the brain, the eye, the nervous system, in short psychophysics. Philosophy, on the other hand, turned out to be profoundly interesting, with topics such as the existence of God, reality, equality, and freedom, even though these ideas were often approached from an analytical or linguistic philosophy point of view. Introduction to philosophy at my university did not begin with the history of philosophy. What was offered was systematic philosophy with a focus on philosophical themes or problems rather than the traditional historical approach starting with the pre-Socratic philosophers and then Greek philosophers, such as Plato and Aristotle, to the Enlightenment and then Modern philosophy.

Fortunately, professional philosophy was approached from two different perspectives, Anglo-American analytic philosophy and what is curiously called “Continental Philosophy,” curious because there are seven continents of the world, yet it is a designation of only one continent. Continental philosophy meant existentialism, hermeneutics, phenomenology, and so on. Introduced early in class to Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s The Phenomenology of Perception and Jean-Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness,23 both dealing with the phenomenology of the body and human freedom, I immediately found myself overwhelmingly attracted and seduced by Sartre. Being in pursuit of freedom, Sartre’s treatment of human freedom, responsibility, choice, agency, bad faith, consciousness, and suffering had a profound influence on me. From then on, I knew that this was the kind of philosophy I wanted to pursue as a life-goal. I simply got hooked on existentialism and ended up with a PhD on Sartre and racism. The main lesson I learned from my love of philosophy is that unlike other disciplines that prepare you for the job market in order to make money, philosophy is about mental liberation and freedom.

Freedom and suffering are infinitely and intimately linked and interrelated. Consider Sartre’s seemingly paradoxical statement during the German occupation of France in World War II: “We were never more free than during the German occupation.”24 Freedom is experienced through the act of resisting suffering. Suffering, by its very nature, requires its own elimination, that is freedom from suffering. Indeed, as Sartre with his characteristically Hegelian flair, puts it: “Suffering carries within itself its own refusal…it opens onto revolt and liberty.”25 In other words, the suffering which I and many other Black South Africans endured, carried within itself a rejection of suffering. This knowledge of suffering offered me a glimmer of hope for the future, an optimism, a hope that things need not be as they are, that, as African-American soul singer Sam Cooke says, “A Change is Gonna Come” (1963). Hope for the future and a sense that our suffering and sacrifices had meaning were among the very conditions for resistance, resilience, and survival in the face of the brutality of apartheid. They were also the condition of possibility for my pursuit of philosophical immersion. Without hope, there is utter despair, nihilism, anguish, and trembling. With hope, there is the conviction of inexorable progress toward freedom.

The work of Sartre on consciousness likewise threw me inexorably into Black Consciousness philosophy. My undergrad period at the University of the North was the period that birthed the South African Students’ Organisation (SASO), a break-away Black student movement from the white-dominated National Union of South African Students (NUSAS). The impact of Sartre and existentialism on my appreciation and understanding of Black Consciousness philosophy was immense. This relation between Sartre and Black Consciousness led to my first book, Biko: Philosophy, Identity, and Liberation.26 Indeed, the Sartrean sensibility requires that philosophizing be linked directly to existentially concrete situations.

The philosophical work of Frantz Fanon also contributed immensely to my philosophical development. When I clandestinely read Fanon’s books – his books were banned by the apartheid regime Censorship Board under the Suppression of Communism Act. No 44 of 1950 – it dawned on me that my own life was reflected by what Fanon said in his analysis of the colonial and racist system. I grew up in a township that was consistent with the Manichaean structure of colonial settlement described by Fanon in the Wretched of the Earth (1968) and the alienation that I experienced as articulated in his Black Skin, White Masks (1967). Noel Chabani Manganyi’s classic book, Being-Black-in-the-World (1973), which appeared immediately after my junior degree, was also immensely influential not only in its contents, but also because for the first time a Black man courageously and defiantly published a philosophical text in the face of constant intimidation by the apartheid regime. Given that he was a psychologist, Manganyi became a distant role model for me, distant because he was in a different field, psychology, but important as a Black intellectual. He demonstrated to me that a Black man could engage in philosophical thought with such ease. My first aborted PhD at the University of Cape Town was based on his work.

Finally, one is not born with a particular nature, a particular determinate, predestined being. Professors of philosophy are first and foremost human beings before they become professors. In other words, one is not born a philosopher but becomes a philosopher just as, in the famous words of Simone de Beauvoir, “one is not born but becomes a woman.”27 No one is born anything except human. Every one of us makes or chooses to become something. A woman is born female but chooses to become a woman by doing so-called womanish things. A person first exists as a biological male or female, and thereafter, becomes that which they make of themselves. This means that a human being is nothing but the sum of their actions. A criminal or a priest, for example, makes themself criminal or priestly through their actions. And each one of us – precisely because we choose ourselves individually – is responsible for what we become. I am who and what I chose to be. Therefore, the whole responsibility for my choice rests on my shoulders. So, I was not born a philosopher, I chose to be a philosopher through my actions and I have to take responsibility for what it means and entails to be perceived as such.

Because of the suffering brought about by grand apartheid and the dehumanization resulting from it, some of us acquired and developed a sense of revolt and a love of freedom. As a consequence, philosophy for me became a needing-to-be, the desire and hope to be someone different from what I was, a changed being, a free being. Philosophy made me and I tried to make philosophy. It offered me a survivalist and radical consciousness that enabled me to face the limitations placed before me and to philosophize.

JAG – In your 2020 interview with Rosemere Ferreira da Silva, you describe how the language spoken in the townships where you came of age was a creolized/patois language that conjoined linguistic elements of the Pedis, the Tshangaans, Vendas, and Xhosas, among others. When speaking with students’ movements for decolonizing the curriculum and South African life in general, what is your response to the absence of philosophical literature written in students’ mother tongues? Is it vital, existentially, intellectually, and politically, for it to reflect the full range of mother tongues, both radically creolized ones and those of the many distinct nations that compose Azania?

MPM – Let me first begin by saying that the centrality of language in any (post)-colonial country cannot be overemphasized. It is an issue that confronted African philosophers, literary scholars, and intellectuals in general. The “Language Question” in African literature, indeed in African philosophy as well, has been one of the most contested issues in both colonial and postcolonial discourse. The dilemma of writing in the mother tongue or colonizer’s language is a subject that has generated passionate responses from African writers such as Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, Ama Ata Aidoo, Chinua Achebe, Gabriel Okara, Es’kia Mphahlele, Wole Soyinka, and many others.

This discourse has in the main been a debate between two rival positions, namely: (a) The Retentionist Argument and (b) The Culturalist Argument. For the former position, European languages play a socio-political unifying role in the midst of linguistic fissures created by a plethora of diverse linguistic segments of contemporary African communities. European languages serve as a cohesive, unifying force in Africa’s postcolonial nations and therefore should be encouraged. A lighter version of the retentionist position is the “domestication” thesis, which is an attempt to fuse African language phrasing with English, an English less marked by English culture. For example, Chinua Achebe, Es’kia Mphahlele, and Gabriel Okara have attempted to develop this hybrid language in which English is localized in accordance with African idioms, metaphors, symbolism, and African experiences. Another version of domestication in South Africa is the urban creolized languages of the townships, variously referred to as “flytaal,” “Tsotsitaal,” “Wittie,” or “Isicamtho.”28 The problem with these creole languages is that there is no single version that can be adopted nationally. Such creole languages are not only regional, they are also predominantly city languages, different from rural languages, and differing from one city to another. Even if Afrikaans, as the base, is the same, and then welded with Spanish, English, Zulu, Sotho, Venda, Pedi, and Xhosa words, there are serious regional differences that render writing in these creolized languages problematically limited.

The culturalists reject the use of European languages in literature or philosophy for the simple reason that to learn and speak a language, in Fanon’s view, is to take on its world, its culture. The argument here is that if the African heritage and cultural difference have to be protected, preserved, and maintained. African languages are the vehicles through which this political, historical, cultural, and philosophical specificity can be achieved. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o is the dominant figure of the culturalist position. Echoing the Sapir-Whorf linguistic determinism hypothesis, he articulated the view that language determines a person’s basic ontology and cultural metaphysics. Ngũgĩ then conceives of language as a reservoir of culture with ontological status and a tool or technology of power. In this respect, he argues that the domination of native languages by languages of the imperial powers is critical to the domination of the mental universe of the colonised.

There is much to be said in support of Ngũgĩ’s position. Consider the painful truth of Sartre’s observations in “Black Orpheus,” an observation which we confronted during the heydays of apartheid. According to him, for activists and resistance movements to incite and call for solidarity among the colonized oppressed, the leaders necessarily had to rely on the language of the oppressor. This meant that the colonist became the mediator between the colonized masses and their leaders, a presence in an absence even in the most secret meetings. The problem then is that the words and syntax of the colonizer’s language are basically unsuitable to provide the colonized with the means of speaking about themselves and their own aspirations. Sartre’s observation raises the same problem raised by Audre Lorde’s “The Master’s Tools will Never Dismantle the Master’s House.” Such tools, Lorde argues, “may allow us temporarily to beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change.”29 To speak and use the oppressor’s language to liberate oneself from the oppressor’s oppression is ironically to dangerously slow down the very effort of liberation.

At the political and ideological level, language becomes an instrument of power tied to class, race, and culture. In a colonial or neo-colonial situation, only a few acquire petit-bourgeois (intellectual) status through colonial education. Since every language has words full of ideological connotations and are value laden, those who learn the language absorb and interiorize the ideology of the ruling class. They begin to see the language and values of the coloniser as a means of enlightenment and social progress. As they seek to be European, the colonised are increasingly alienated from their individuality and culture, in short, from their Africanity.

Colonial consciousness has unfortunately sunk deep into the psyche of most Black South Africans such that, to use Fanon again, the African in South Africa is proportionately whiter, that is, they will come closer to being a real human being in direct proportion to their mastery of the English language. English has infiltrated the African’s secret corners: homes, meetings, social gatherings, literature, philosophy, movies, television, mobile phones, laptops, government notices, court procedures, advertisements, public facilities, family, and interpersonal relations. It is, however, mostly a class phenomenon, a predominantly middle-class trend through which Black families prefer English and Black pupils are forced to speak English not only at school but even at home. Most bourgeois Africans, realizing the painful reality that European languages are not only those of centers of power but also of global opportunity and survival, develop pathological disdain for their own African languages. Thus, in many ways, the language of the colonist in a post-colonial context is used against the native languages. Until the skewed existing power relations between the West and Africa are transformed, the inequalities and hierarchization of languages will remain intact. Given these existing power relations, the possibilities of successfully using African languages in philosophy and literature seem remote.

Given the practical, economic, class, ethnic, and even social problems associated with writing in (m)other tongues, perhaps a more rational approach under the present prevailing power relations between the West and Africa is to posit what psycholinguists call coordinate bilingualism. This is the view that human beings have the ability to operate in two or more languages in such a way that neither language and its cultural or worldview baggage becomes hegemonic. Such a person is able to cross cultural and cognitive boundaries to a different mental universe each time they speak either language. In essence, as Ali Al’amin Mazrui points out, “a coordinate bilingual ‘controls’ two cultures and two ‘worldviews’ corresponding to the two languages in his/her repertoire.”30 In my view, this position expresses a weaker culturalist position which claims that, because language influences cognition in a culturally specific manner, the privileging of African languages in Africa for Africans is a necessary condition for the maintenance and protection of African cultural difference. The central concept here is “privileging” because it does not completely exclude other languages but strongly recommends the use of indigenous languages. There are, to be sure, other equally competing influences on cultural specificity. But, the advantage of this view is that, because of its anti-determinism, it creates space for Africans to denounce the privileging of foreign languages while writing in English themselves.

Since the majority of Blacks in South Africa speak one of the nine African languages, efforts have been underway to write in some of these languages. For example, recently, Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth was translated into Zulu by Dr. Makhosazana Xaba. I recommended that a series of excerpts from that translation be published in the local daily and weekly Zulu newspapers, such as Isolezwe and Ilanga. Because of the high rate of unemployment, a lot of people cannot afford to or even think of buying books. However, most people do have access to newspapers. The problem here is that this translation is for a certain ethnic group and therefore is not accessible to other non-Zulu-speaking South Africans, such as the Tshivenda, Xhosa, Pedi, Tswana, Ndebele, and Sotho speaking peoples. This would mean translations into these other languages. In philosophy, Mogobe Ramose has begun writing the abstracts of his South African Journal of Philosophy publications in Setswana. I hope he will follow this up with a full-length article in Setswana.

JAG – You reflect poignantly on how “one has to pay [the] price for trying to ‘tell it like it is.’”31 After all, you devoted your intellectual life to articulating the lived experience of being Black or doing philosophy in Black, perspectives that are generally denied significance in an antiblack world. Among the “prices” were forced retirement and lack of recognition from your national community. Is there a particular way of understanding the kind of fight and struggle undertaken in and through intellectual and educational work? Is there a particular temporality to this fight, even when its aim is to respond with a sense of urgency to immediacy?

MPM – I think we should first start with the existentialist notion of freedom and responsibility. The choice of “telling it like it is” was a free act of commitment to a particular cause and involved taking responsibility for that choice. This means that the “price” of forced retirement and non-recognition emanate from the very choices I made and therefore I have to take responsibility for them. For example, while a Black subject is always free to interpret their Blackness positively or negatively, they are not free to change into a White subject. If this were possible, then the Black subject would be his own foundation, an equivalent of God, ens causa sui, because total freedom can exist only for a being which is its own foundation, in other words responsible for its facticity.

That I am Black is a given, it is my facticity, but it is the meaning I give to my Blackness that gives it its significance. My facticity paradoxically limits my freedom while constituting the very conditions against which my freedom can manifest itself. However, within a world where it is easy and comfortable to live one’s life in terms of social demands and prescriptions, and thus in bad faith, to be one’s own freedom, a rebel, a nonconformist, a being who refuses to play the game according to certain well-established and revered rules, carries with it a heavy price. This means that an individual is free, as Sartre would say, “because he can always choose to accept his lot with resignation or to rebel against it.”32

After my retirement, I realized that the route to centering is situational. This means that I became conscious of the fact that I need to demand and appropriate spaces, intellectually and physically, in any situation that may present itself, no matter the obstructions that I may encounter. Because I no longer had direct access to students, I could, among many ways, fight against being invisibilized and ignored through producing texts. In South Africa, as I have indicated in the Memoirs, being a full-time professor requires extraordinary talent, intelligence, and commitment to teach with all the attendant responsibilities (e.g. the large numbers in classes, grading assignment essays, test scripts, and exams, departmental, faculty, and senate meetings). Compared to U.S. professors, South African professors have a lot of administrative and heavy teaching loads that render them almost incapable of producing voluminous research projects. U.S. professors have Teaching Assistants (TAs) who relieve them of the heavy teaching loads that South African professors have to endure. This explains the paucity of research production in this country.

On retirement, despite the fact that I had already accumulated a substantial number of journal publications, I then – given the time and space I had at my disposal – focused on writing books. Hence my four books were all written after retirement. The aim here was that since I had no direct access to students, the only way to reach them was through books. Except for Sartre on Contingency: Antiblack Racism and Embodiment (2021), my other three books were written with the primary aim of humanizing philosophy. Such a philosophy is not exactly a humanist philosophy but one that encompasses the lived experiences of Black people, a philosophy which is, as Biko and the Black Consciousness Movement conceived it, “a way of life.” Philosophy as a way of life has as its fundamental project the radical and concrete transformation of the being of the individual, a bringing into emergence of a certain way of being-in-the-world. Such a philosophical outlook does not attempt to construct a technical jargon reserved for specialists or esoteric abstract language used mostly by professional philosophers, but focuses on communicating with the being of the individual person in their own lived-experiential language.

Another way of continuing the fight was to involve myself with and to use my philosophical skill in NGOs and civil society movements. I immediately rejoined the Workers’ College, where I had previously facilitated discussions on Marx, Fanon, liberalism, fascism, capitalism, socialism, and community development projects. Such work and commitment is not time bound. It transcends temporal limits irrespective of who is in power, especially in the “post-apartheid” situation, which follows Fanon’s characterization as simply a replacement of one kind of face by another. A significant part of my work is to locate and give credit to the work of intellectuals who indeed recognized aspects of the truth but were denigrated as heretical, or who have gone unrecognized in the ongoing racist climate.

JAG – What does engaging in a philosophical life offer Black women and Black LGBTQIA+ scholars that would make it attractive to them in comparison to the financial and social status benefits afforded by medicine, law, economics, or politics? I am thinking of this question particularly given your framing of your Memoirs as addressed to your daughter who might not have previously understood who you were as a person.

MPM – I am not sure whether I grasp this question fully, but let me proffer an answer. What philosophy as a profession or as a career can offer Black women and Black LGBTQIA+ people is exactly what it can also offer Black men, White women, and people of any gender and sexual orientation in terms of, for example, job security, a certain social status, travelling opportunities, conference attendance, etc. However, the philosophical content which offers itself as philosophy to Black women and Black LGBTQIA+ people in particular is of paramount importance because it will either empower or dehumanize them. Entry into a space in which you contemplate issues about your situation, for me, takes precedence over simply being in philosophy for philosophy’s sake. Relevant philosophy, for both Black women and men, offers an integrative power to connect ideas from different points of view across disciplinary differences.

Beyond this, I doubt whether academic philosophy per se has something special and unique to offer Black women. Philosophy is not a first order concept referring us to an entity, object, or thing called philosophy. Philosophy is the activities of human thinking beings. It is human beings who make philosophy and not the other way round. Indeed, we certainly need Black women and Black LGBTQIA+ philosophers but this should not be the major career path for them, important as philosophy is. We need Black women and LGBTQIA+ people to occupy every academic disciplinary space at every level at universities. Black women and LGBTQIA+ people are not passive observers, acted upon by philosophy, they act upon the discipline. The issue, as Anita Allen has pointed out, is more of what do Black women offer philosophy and less of what does philosophy offer Black women.33 In other words, what do Black women bring to philosophy which is unique and advances the expansion and progress of philosophy? By virtue of their embodiment and situatedness within the context of a profession that is both sexist and racist, a profession and indeed a world that does not take them seriously and questions their critical and original thought, Black women and LGBTQIA+ people bring a unique contribution to philosophy through their exploration of the ontological, political, social, and epistemological implications of what it means to be a Black woman and LGBTQIA+ in philosophy. This means that, from Black women’s and other oppressed groups’ point of view, writing philosophy brings to bear on any philosophizing endeavor a gender, racial, and sexual orientation, a set of values, a different conceptualization of such phenomena as embodiment, time, space, and subjectivity, different competing theories of knowledge, highly specialized forms of language, and the architecture of power. In short, they bring to the philosophical table a philosophy of difference, that is, ideas about gender, race, and sexual orientation and what these issues mean for society can be of value to philosophy.

I am here not making a generalizing claim about all Black women and all LGBTQIA+ groups. I am simply saying that those who are conscious about their identities and how they are perceived and reacted to in the profession of philosophy will bring this uniqueness into the discipline. One such area of contribution is Black feminist philosophy. Black women have the capacity to expand the scope of philosophical discourse through contributions about identity and Black feminist theory. When Black women and Black LGBTQIA+ people are interested and are active participants in philosophical discourses, they certainly contribute perspectives and argue in ways that enrich the experience of philosophy for everyone. I can think of the myriad contributions Black women have made in philosophy, for example, Nkiru Nzegwu has contributed a number of journal articles, book chapters, and books on African aesthetics, epistemology, African feminism, and African diaspora art. Her book Family Matters: Feminist Concepts in African Philosophy and Culture (2006) is a classic in its own right. She is also the co-founder of the International Society for African Philosophy and Studies journal. Sophie B. Oluwole headed the Department of Philosophy at the University of Lagos for years and helped in developing philosophy in Nigeria. Marie Paulin Eboh’s contribution to Nigerian philosophy and Black women’s emancipation is well known. Professor Ratnamala Singh, who brought me to Durban and was the Head of the Department of Philosophy at the University of Durban Westville, contributed enormously to philosophy and education in South Africa. The contributions of Joyce Mitchell Cook, Angela Davis, Anita Allen, Kathryn Sophia Belle, and many others cannot be overstated.

JAG – I am returning to the States now from the Conference of the Centre for Phenomenology in South Africa, held in the Eastern Cape, inspired to construct a semester-long course on South African political thought. To reflect the full range of contributions, such a class would not only include written texts, but also photographs, music (perhaps also liner notes), and creative literature rich with theoretical insights. (With photography, I was particularly convinced by Tendayi Sithole’s powerful presentation on Ernest Cole’s A House of Bondage.) If you were offering such a seminar right now, which figures and works would be indispensable and why?

MPM – A seminar on South African political thought, I think, would depend on whether the approach is historical, theoretical (ideological), or thematic. A historical approach would require an account of the development of political thought from pre-colonial time to the present and an engagement with the available literature. The theoretical approach would involve certain types of theories about the origins of political arrangements, the basis of political institutions, and the theoretical justification of certain political systems. In the thematic approach, certain themes and problems peculiar to political thought would be examined and analyzed. It seems to me that a combined historical and theoretical approach would involve the histories of communism, liberalism, trade unionism, capitalism, Pan-Africanism, Afrikaner Calvinism, Marxism, Black Consciousness, Liberalism, etc., but these are at the same time also ideologies (theories).

There are innumerable texts that can be utilized in a seminar course on political thought in South Africa. Starting with work from philosophers, one can then move to work by political scientists and political activists. Among the texts that I think would cover the historical and theoretical frameworks that are relevant are the following:

Richard Turner, The Eye of the Needle: Towards Participatory Democracy in South Africa (1972). Turner is important for his concerns with pollical philosophy and with justice. He defends what he calls “participatory democracy” as opposed to representative democracy. Utilizing Sartre’s Critique of Dialectical Reason (1982), Turner defends the view of dialectical reason as critique of the South African oppressive system, that is, the dialectic of emancipation and domination. He then theorizes what he calls “participatory democracy,” which involves participation by more lay citizen in decision making. Steve Biko, I Write What I Like (1978) on the political philosophy of Black Consciousness. There is much written about Steve Biko and Black Consciousness philosophy that deserves close attention. Mogobe B. Ramose, African Philosophy Through Ubuntu (1999). This is an Africanist ethical and political theory in South Africa. Ramose again in The African Philosophy Reader (2nd edition), edited by P.H. Coetzee and A.P.J. Roux (2003). In several chapters in the text, Ramose theorizes about land restitution in South Africa. The papers included in this collection appeared earlier in different journals. David Theo Goldberg’s The Racial State (2002) is about the formation of a racial state in which he argues race is integral to the conceptual, philosophical, and material emergence of the modern nation-state’s creation. Another important contribution to South African political thought is Goldberg’s The Threat of Race: Reflections on Racial Neoliberalism (2008). This text is an account of the historical production of race. It contains an informative chapter on South African racism, “A Political Theology of Race (On Racial Southafricanism).” Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth (1968). Fanon’s critique of post-colonial African governments is appropriate for the South African post-apartheid condition. N. Chabani Manganyi and Andre du Toit’s Political Violence and the Struggle in South Africa (1990). This is a theorization of political violence as a means of liberation from apartheid by the political philosopher Andre du Toit and Africana psychologist-philosopher Chabani Manganyi.

Political leaders also contributed to political thought in South Africa. Among these I could think of Govan Mbeki’s South Africa: The Peasant Revolt (1962). Mbeki was a Marxist theoretician and a communist party leader who supported the Pondoland peasant revolt in 1960. The Pan-Africanist leader Robert Mangaliso Sobukwe’s contribution was published as Speeches of Mangaliso Sobukwe (1989). Since political thought in South Africa did not emerge ex nihilo, a lot of influences should be included as background reading, for example Kwame Nkrumah’s Consciencism (1964), Neocolonialism: The Last Stage of Imperialism (1965), and Class Struggle in Africa (1970) and Julius Nyerere’s Ujamaa: Essays on Socialism (1968).

Additional important resources are contributions from academics in other disciplines apart from philosophy. The relevant discourses center around the thorny and typically South African race/class debate. For example, the former University of Connecticut Professor of Sociology, Bernard Magubane published an important book, Political Economy of Race and Class in South Africa (1979), which is a Marxist defense of class over race in the South African political space. Sam C. Nolutshungu’s Changing South Africa: Political Considerations (1982) is a prioritization of race over class in South Africa. Further readings may include Peter Vale, Lawrence Hamilton, and Estelle H. Prinsloo’s edited collection, Intellectual Traditions in South Africa (2014), C.R.D. Halisi’s Black Political Thought in the Making of South African Democracy (1999), Robert Fatton’s Black Consciousness in South Africa: Dialectics of Ideological Resistance to White Supremacy (1986), Lou Turner and John Alan’s Frantz Fanon, Soweto and American Black Thought (1986). Several journal articles would also be of value for the course. For example, Andre du Toit’s “Philosophy in a Changing Society” (1982) and Johan Degenaar’s “Ideologies: Ways of Looking at South Africa” (1983). This list is not exhaustive. Quite a lot of texts written especially by white liberals and Afrikaner academics would make the list either as main readings or as further readings.

During the height of grand apartheid in the 1970s and 1980s, several revolutionary and left-wing publications, magazines, newsletters, pamphlets, and labor bulletins played an important part in articulating political thought. Examples are Frank Talk, a publication by the Azanian Political Organization (AZAPO), established in 1984. It contains local and international news, essays, and pictures of the struggle. Inkululeko (meaning Freedom), a South African Communist Party publication, Sechaba (meaning The Nation), the official organ of the African National Congress, Staffrider, a political and literary magazine established in 1984 by AZAPO. Another important publication is The African Communist, a publication of the South African Communist Party. SASO Newsletter, together with its wing, Black Community Programmes’ Black Review (first published in 1973) would provide invaluable material for such a seminar.

A valuable resource of political photographs of apartheid South Africa and resistance to it is the collection of legendary photographer Peter Magubane. His photos capture the whole spectrum of apartheid brutality and Black people’s resistance to oppression. Certain films may also be of value in articulating the political thinking of various periods of apartheid era, for example, Cry Freedom: Apartheid and the Tragedy of South Africa (Richard Attenborough) and documentary films, such as Bob van Lierop’s A Luta Continua and Nana Mohamo’s films, such as Generations of Resistance and The Last Grave at Dimbaza.

JAG – When I first wrote about statelessness, I was galvanized to continue when you immediately contacted me to describe how the analysis resonated with your experience as a Black South African. In my current work, I am exploring the extent to which Black U.S. southerners who fled to the U.S. north at the end of the nineteenth and start of the twentieth centuries were in fact living in a condition of perpetual exile and statelessness. Would you reflect on what the concept of statelessness illuminates in specific ways that other terms might miss or obscure?

MPM – Two of the modes of statelessness you identify in your text, Statelessness and Contemporary Enslavement (2020), are “being pushed out of a state”34 and “when the concrete value of political membership is eroded.”35 When I read your book, I was immediately thrown back in time to the years 1971 and 1979 in my life as a stateless individual. In 1979 I applied for a passport to study at Indiana University (USA). The apartheid South African regime refused to give me a South African passport but insisted that since I was ethnically a Motswana, I should get a Bophuthatswana Bantustan government passport. In point of fact, this was not the first time I was denied recognition. When I went to study at the University of the North, which was located in a soon-to-be Bantustan called Lebowa, I was in terms of the Section 10 of the Group Areas Act of 1952 stripped of my city-dweller status. This Act was passed to limit the rights of Black people to permanent residence in the urban areas which were by law white Areas. Under this Act were section 10.1a, 10.1b, and 10.1c. Section 10.1a gave Blacks the right to be in urban areas only as long as they were in the employment of whites. Section 10.1b stipulated that if you leave the urban area for more than three months, you forfeit your section 10.1a status, that is, you lose your right to work or live in the urban area. Because I left for university for over six months and accumulatively three years, I was then stripped of my urban area permit, that is, deprived of my section 10.1a status and left stateless since I had no connections whatsoever with any rural or Bantustan area except the University of the North.

So, the passport issue was not the first time I was rendered non-South African. Needless to say, this Bantustan passport would not have given me entry into any country. After long battles and representation from the International Institute of Education (IIE), which was offering me the scholarship to Indiana University, I was ultimately given something similar to but not quite a passport, a “Document for Traveling Purposes.” On the first page, under “Nationality,” my travelling document was written in Afrikaans: Onbepaldbaar (Undetermined). This effectively meant I had no country, I was stateless, and could not travel to other countries without being a citizen or national of any country. As it turned out, the U.S. and British governments had agreed to allow Blacks who carried such documents entry into their countries. However, on entry you were given a permit, and the traveling document was not stamped at all on the relevant entry pages.

I was certainly not the only one rendered stateless. The popular South Africa musician, Sipho “Hotstix” Mabuse, in a November 3, 2024 “Talk to Al Jazeera” program, recounted how his two children were given the same “Document for Traveling Purposes” with their nationality Onbepaldbaar (Undetermined) and thus rendered stateless. Mabuse then asks the interviewer: “What do you do as a parent when your children are declared stateless?” He answered: “Fight!!” Indeed, all Africans were designated non-citizens of the Republic of South Africa which was considered a white state, a European state in Africa. Within this polity, Africans could be enslaved at will. Because the Chief Ministers of the Zulus, Pedis, Sothos, Shangaans, Swazis, and Ndebeles refused to be declared “independent” by the apartheid regime, their peoples were rendered stateless and non-citizens of white South Africa and therefore subject to enslavement on white-owned farms. The condition of being without a state or not being a citizen or not belonging to any country, as you have accurately observed, is “to have no place to go, not due to lack of space but because to be thrown out of one’s nation has often meant to be thrown outside of nations altogether.”36 This relates to the significance of the country called South Africa and a Black territory to be named Azania, a country in which no one is rendered stateless. The former is a whites-only country while the latter is a truly African country that accommodates everyone.

I have – at the time of writing this response – been watching a four-part documentary on Al Jazeera titled “Stateless in Syria.” It is a story about a Muslim British-born citizen, Tauriq Sharif, who is an aid worker in Syria and has his British citizenship revoked because of alleged sympathies with al-Qaeda. To compound his problems, Sharif was also detained and tortured by the Syrian jihadists, the Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), and charged with funding projects that incite division. Whether the accusations are true or not, the point is that here’s a situation in which one is stateless within a state. All of us who had their citizenship revoked or denied had our revocation within a particular state and were still subjected to prosecution through the laws of that very state that paradoxically rendered us stateless. Our condition was ironically statelessness within a state.

What are the personal or subjective implications for such a situation? Statelessness is a subjective condition and, at this level, generates a feeling of belonginglessness, nationlessness (denationalization), citizenshiplessness, non-recognition, invisibility, non-being, dehumanization, and an acute sense of alienation. Es’kia Mphahlele, one of South Africa’s great literary figures, describes this experience of statelessness and exile as “the tyranny of place.”37 Chabani Manganyi had the same feeling of statelessness and the anguish of being exiled in his Mashangu’s Reverie in 1977. Statelessness is a sense of absolute alienation, what Viktor Frankl describes as a strong feeling of “existential vacuum” (1968) that is, the experience of total lack of meaning in one’s life. I suppose these feelings or emotions are also experienced by slaves.

JAG – While I was familiar with the history of apartheid education in South Africa, it was still striking to read about primarily white professor farmers who, without what we would now call requisite credentials, expressed such profound disdain for their students in the classroom and when serving as security in the afternoons and evenings, monitoring and reporting on student political activities that they deemed dangerous. At the same time, this was an institution where you went on to teach and to which, at the end of your career, you returned. You emphasize quite how significant a site University of the North (Turfloop) was for the emergence of Black political leaders, including Cyril Ramaphosa, and intellectuals, among them, N. Chabanyi Manganyi and yourself. How did an institution so hostile to Black freedom still manage to contribute so meaningfully to it? What lessons from this seeming contradiction might we glean for contemporary efforts to transform South African higher education much more radically? How does creating genuinely Azanian institutions of higher learning require different kinds of relationships of South Africa to the rest of the African continent?

MPM – I think that first and foremost, we should recognize that the contradictions in any society are a product of a conflict of values, and personal values are derived from personal circumstances, such as class location, educational achievements, political consciousness, religious affiliations, family, personal experiences, and individual personality structure. This means that because of these positional values, not all individuals will react the same way to oppressive structures and conditions. If this was not possible, there would be a complete absence of revolutionary and rebellious consciousness among the oppressed. In every oppressive situation there are of course individuals who will oppose such structures and conditions, individuals who, though living under such oppressive conditions, give a different meaning to their situation. Of course, an argument can be made for the social conditioning of individual personalities in certain societies with certain social relations between or among different groups. Yet, there is a psychological and existential fact that, for instance, reactions to stressful situations are highly individualized and based on a complex set of factors that constitute the personality profile of the individual concerned.