Rena Rädle and Vladan Jeremić, Paris Commune Revisited/Komuna e Parisit Revisited, 2019.

Transformative action, commissioned by Tirana Art Lab (TAL).

Introduction: The Sound of a Gun Being Loaded

The first nearly 20 seconds of Armando Lulaj’s video Live, Sunday, May 17, 2020, 4:31AM take place in total darkness1. About 18 seconds into the video, we see a few flashes of light at right, then darkness again, until more than 30 seconds have passed. 44 seconds into the video, a flashlight at lower left rakes across the screen and we realize we are inside a theater—we see the rows of seats illuminated briefly, before the screen returns to blackness. We remain in this darkness, punctuated by brief bursts of light, for almost all of the work’s 9 minutes and 45 seconds. During this time, we hear loud rustling, shouting, voices speaking in Albanian—their words often indistinguishable. Just past the 7-minute mark, a loud banging sound begins to break through the other sounds, and after about another minute the crashing noise reaches a height, echoing in the darkness, followed by a sudden outburst of frantic shouts. In the final 30 seconds of the video, we are finally able to see, as light from flashlights bathes the space. Accompanying the sudden wash of light is the sound of a gun being loaded. Armed police with flashlights mounted on rifles enter the camera’s view: the camera’s position is low to the ground, and we see the boots of one officer as he approaches and orders the person filming to get up. He appears to seize her, as we hear her voice: “Ok, calm down, I’ll get up on my own, I’ll get up on my own”2. One of the officers orders her to put her phone away. She hurriedly says she will put it away. The video ends abruptly.

Armando Lulaj, Live, Sunday, May 17, 2020, 4:31AM, 2021.

Video, color, sound, 9’45”.

Lulaj’s video was created from footage filmed by architect Doriana Musaj, a member of the activist group The Alliance for the Protection of the Theater (Aleanca për Mbrojtjen e Teatrit, often simply called the Alliance for the Theater), and it was taken inside the National Theater of Albania on the morning of the day the building was destroyed. A group of activists—including artists, architects, and heritage professionals—had been occupying the theater as part of an ongoing protest against its demolition. The protest began in February 2018, when word circulated that the theater would be demolished and replaced by a new theater, together with a number of new commercial and residential towers constructed on a portion of the site3. Over the course of more than two years, the movement to preserve the theater became the longest-running protest in Albania’s history, according to news reports4. Activists hung a banner with the words “#ProtecttheTheater” (“#MbroTeatrin”) at the site. The phrase “I am the Theater” (“Unë jam Teatri”) circulated on social media in support of the protests. Members of the Alliance for the Theater reached out to foreign heritage and preservation organizations for support; in March of 2020 Europa Nostra added the theater to its list of most endangered heritage sites in Europe, after having first expressed its support for the building’s preservation in 20185. Until the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic—and the tightened restrictions on public gatherings—the Alliance for the Theater held regular meetings, open mic forums, and performances in the plaza adjacent to the theater building. Early on the morning of May 17, after police violently ejected the activists occupying the building, injuring some and arresting several, the building was summarily demolished.

What was this theater that engendered such ardent support, and that the Albanian government saw fit to destroy so suddenly, with such a militaristic demonstration of force? Designed in 1938 by the Italian architect Giulio Bertè and completed in 1940, the theater first served as a multipurpose center of culture and sport during the period of the Italian Protectorate in Albania6. Subsequently, in the postwar period, under state socialism, the theater was the site of the first show trials held by the communist regime, and subsequently took on its function as a theater. Located adjacent to the National Gallery of Art, the National Theater was a visually distinct element of Tirana’s historic center, a quintessential visual remnant of the Italian Empire’s effort to modernize the capital city’s urban space. In 2018, after initial rumors began to circulate about the theater’s destruction—and what would replace it—the Albanian government revealed a plan for a new theater, designed by the well-known Danish architecture firm Bjarke Ingels Group (BIG). The proposed destruction of the theater unified a protest movement that included architects, artists, actors, writers, heritage experts, and other members of civil society—it was a movement that brought into stark relief the complexity of urban politics and community memory in contemporary Albania.

Armando Lulaj, Live, Sunday, May 17, 2020, 4:31AM, 2021.

Video, color, sound, 9’45”.

The global artworld was perplexed by the apparent attachment to a building created by fascist occupiers, a clear remnant of colonialism. Their confusion was compounded by the fact that major artistic figures close to Edi Rama, such as Anri Sala, had declared the protests to be merely a tool of the opposition party in Albania, an effort to manufacture dissent7. As such, when more protests broke out after the demolition, some artworld figures8 took to social media to suggest that the protests were an example of the widespread resurgence of right-wing populism in Europe and beyond, which has often sought to recuperate fascist symbols, figures, and legacies. But the National Theater, while recognized as a remnant of fascist occupation, was not widely regarded as a “symbol” of fascism—at least no more so that the building housing the Prime Minister’s offices, which Rama had transformed into a multifunctional art exhibition space in 2016. What the activists who occupied the theater protested was not the destruction of a fascist, colonial structure, but the erosion of the capital city’s historic center, since the theater was only one in a long line of recent projects involving the demolition of historic structures and the remaking of public space. Even more so, they protested the economics of the plan for the site, which gave over a large section of public land for private development.

Armando Lulaj, Live, Sunday, May 17, 2020, 4:31AM, 2021.

Video, color, sound, 9’45”.

Ultimately, despite the National Theater’s destruction, the protest successfully brought to the fore the complexities of urban development in contemporary Tirana, and revealed the ways that government power is intertwined with the economic interests of private companies. The Alliance for the Theater also successfully thematized the polysemy inherent in historic architecture—the theater was never simply a sign of fascist empire, nor simply a trace of the violence of the communist show trials. It was both of these, and more: a structure that spatially designated multiple generations of the city’s lived history, and as such also represented the multidimensional character of memory embodied in structures and urban space. At the same time, its destruction represented not merely an effort to modernize the capital city’s cultural infrastructure (as both Tirana mayor Erion Veliaj and Albanian prime minister Edi Rama claimed); it was also another step in normalizing a pattern of development in Tirana’s city center that focuses on the privatization of public spaces, transforming public institutions into retail spaces and high-priced housing units that afford a consumerist experience aligned with the values of global neoliberal capitalism. Finally, it represented a particularly troubling legal direction in the context of contemporary Albanian politics because in order to destroy the theater the government passed a special law that transferred the land directly to a private construction company9, an action widely perceived as illegal by both the general public and experts10.

The protest to protect the National Theater is a profound example of the ways that civil society actors can come together to expose how contemporary neoliberal politics in postcolonial and postsocialist urban contexts function to mask economic profit and the privatization of space by targeting architectural sites that are connected to undesirable histories (in this case, the period of fascist rule and postwar state socialism). In this article, I provide an overview of the National Theater protest, pointing out the various discourses (aesthetic, historical, political, and legal) that the government and the activists utilized at various points throughout the protest. I contextualize the theater’s destruction within a wider discussion of urban transformations in postsocialist Albania, and to pay particular attention to the way that art and activism coalesced around the theater protests. Finally, I will consider the broader theoretical and practical implications posed by the National Theater as counter-heritage (to use Andrew Herscher’s term)11, showing the ways that the protests thematized violence and destruction as part of contemporary (and supposedly progressive) transformations in urban space.

A Brief History

Although this article is not intended as an exhaustive historical analysis of the National Theater itself (either its architecture or its uses)12, it is nonetheless necessary to understand something of the building’s original context, and about its construction, as these details often played central roles in the debates about whether the building merited preservation. The National Theater, first known as the Circolo italo-albanese “Scanderbeg”13, was designed by Giulio Bertè, who served as the director for the Central Office for Construction and Urbanism of Albania14 (located in Tirana) from 1930 to 193515, and who also designed the Presidential Palace (Pallati i Brigadave), among many other structures and urban spaces in the country. Bertè16, along with other Italian architects and planners such as Armando Brasini, Florestano di Fausto, and Gherardo Bosio, had a tremendous impact on Tirana’s urban fabric, transforming the city from—essentially—a minor town into a capital, a role that Tirana first took on in 1920. Bertè had come to Albania in 1929, during a period in which Albanian King Zog’s government had increasingly begun to allocate power to Italy, with which it was closely aligned throughout the interwar period. In April of 1939, Mussolini officially invaded Albania, establishing a Fascist Party, setting up its own government, and taking control of the country’s military.

The infrastructure put in place before and during the Italian fascist occupation would continue to define the trajectory of urbanism in many Albanian cities throughout the socialist period17, and this was especially true in Tirana, a city that had only been designated as the capital in 1920. Bertè, along with Brasini, di Fausto, and Bosio, worked to establish Tirana’s monumental impact, and to define its urban space through a modernist idiom. One primary transformation that reshaped Tirana during the period of Italian alliance and later fascist control was the creation of a long axial boulevard in the heart of the city, one that effectively divided the old Ottoman city from the newer city18. Several official buildings were sited along its length, while the theater (then a multi-use cultural and sportive space that housed a library, as well as the “Savoy” theater, located in its northern section19) was located just off the main boulevard. Bertè’s design for the Circolo “Scanderbeg” has variously been described as Futurist, post-Futurist, and Rationalist20 —its form is undeniably modernist, distinct from many of the other neoclassical official structures created prior. Several commentators (writing in response to its announced demolition) would marshal its stylistic uniqueness as a point in favor of its preservation, calling it “the first modernist building constructed in Tirana”21. Whether one regards the building itself as a particularly innovative or historically unique structure in the context of global modernist architectural heritage, it is undeniable that the National Theater reflected the political and cultural events of its time. Specifically, it demonstrates the importance that Mussolini’s empire placed on mass culture (such as cinema and the theater), and on the coexistence of participatory physical activities (sport) with these more spectatorial cultural forms22. Furthermore, it was part of a definitive ensemble of modernist structures, including the adjacent National Gallery of the Arts (designed by Enver Faja and constructed in 1973-74) and the Hotel ‘Dajti’ (designed by Gherardo Bosio and constructed in 1939-41)23.

After the Italian capitulation, the building’s cinema and theater (located in the northernmost section of the complex) was renamed Kinema “Kosova”; it was later known as the People’s Theater (Teatri Popullor) during the socialist years and eventually—after socialism—as the National Theater (Teatri Kombëtar). For a period, the southern portion of the building served as a café and club for the Albanian Union of Writers. Most historically significant, however, was the fact that the premises of the theater hall were used for the Special Court for War Criminals and Enemies of the People, which took place in the spring of 1945. The Special Court served as a continuation of earlier purges that had targeted both elites and fascist collaborators. Led by Koçi Xoxe, the court carried out 60 trials, executing 17 people and imprisoning 39 others. These trials occupied a liminal space—legally speaking—since they were carried out before the socialist state had established a definitive law on war crimes24. After the trials in the immediate postwar period, the National Theater took on the role that it would have for the remainder of its existence.

“Fascist Italy’s Sawdust Does Not Constitute a Monument of Culture”

There is no small irony in the fact that the National Theater would again become a site of state violence, of erasure, 75 years later. However, before delving deeper into the forms of erasure that played out in 2020, I want to first survey some of the key justifications offered for the theater’s destruction. Perhaps the most universal justification given was the building’s general state of decay. But this was a factor on which both sides—those in favor of demolition, and those against—agreed. Actor Bujar Asqeri, for example, asserted that “microbes and viruses” festering in the building’s rotting materials endangered bath artists and the public. “Mice, beetles, cats, and all kinds of insects” populated the backstage sections of the theater25. Despite these conditions, Asqeri was most frustrated by the fact that—according to him—the community of actors and directors associated with the theater had not been consulted in any way prior to the announcement of the theater’s impending demolition and the plan for the new theater. This lack of transparency with the very community that a new theater would supposedly serve engendered suspicion on the part of many.

In February 2018, asked why the building seemed to have suddenly lost its status as a Monument of Culture protected by Albanian law, Tirana mayor Erion Veliaj replied that “today the government has decided that fascist Italy’s sawdust and scraps of matches do not constitute a Monument of Culture for Albania”26. Veliaj was referring to the use of Populit—a material composed of cement bound together with poplar wood fibers, waste from the production of matches, and seaweed—in the National Theater’s construction. He cited a 2012 study of Italian architecture in Albania that detailed the theater’s material, and the fact that it was constructed rapidly and cheaply in response to the needs of the Italian autarchy at the time27.

Essentially, Veliaj interpreted these contingencies as evidence that the theater held no monumental value, that it was not meant to last and thus that it did not merit preservation. He also referred to the theater as having been a dopolavoro, a specific variety of afterwork recreational club established by the Italian fascists, a characterization that made the theater’s historical associations less savory (essentially identifying it as a leisure spot for a former occupying power). However, authors such as art historian Rubens Shima have contested the claim that the theater was a dopolavoro28. More bluntly, Veliaj juxtaposed the National Theater to the Pyramid, the National History Museum, and the Palace of Congresses (all built in the 1980s), calling them “authentic Albanian constructions” in contrast to the theater, which he dismissed as “fascist heritage”.

Of course, Veliaj’s responses were problematic in a number of ways: they suggested that a building constructed quickly using what were—at the time—innovative building techniques meant to save time and money somehow held no historical significance for precisely those reasons. He also interpreted the subsequent changes made to the structure (during the socialist era, for example) as further evidence of its inauthenticity, rather than—as architects and historical preservation experts might instead argue—as evidence of the structure’s change over time and its value as a document of precisely those historical shifts.

The question of whether the theater itself merited preservation was also related to broader debates about which segments of Tirana’s center were protected by law. In the case of the theater, its protected status was ambiguous due to a series of conflicting decisions and ordinances from the Council of Ministers and the Ministry of Culture: an April 2000 decision protected the entire urban ensemble that included the building, and a subsequent 2015 ordinance provisionally protected the theater from intervention pending further research on its historical status. In 2017, however, the area of the protected urban ensemble was redrawn, excluding the National Theater complex29. The potential significance of these conflicting redefinitions of the theater was never fully addressed by either prime minister Edi Rama’s government or the Tirana municipality under Erion Veliaj—instead, they primarily relied on claims about the building’s dilapidated state (and its detrimental effects on both actors and the public) and its associations with fascism to dismiss calls to preserve or reconstruct the existing structure.

The complexity of the issue, however, also stems from the broader pattern of urban change in Albania’s capital city over the past several years, primarily coincident with the election of Edi Rama as prime minister of Albania (in 2013) and Erion Veliaj as mayor of Tirana (in 2015). Critics of these changes often refer to the “tower-ification” (kullëzimi) and “concrete-ification” (betonizimi) of Tirana30, in reference to the substantial number of new construction projects introduced in the city31, including a large number of towers surrounding the city center32. These new constructions have sometimes entailed the demolition of existing historic buildings; for example, in 2016, Qemal Stafa Stadium (the national stadium originally designed by Gherardo Bosio, which was partially constructed before the Second World War and completed after the war) was demolished to make way for the new Air Albania Stadium33. The new stadium possesses a substantially increased visual impact, largely due to the presence of a 24-story tower at its northern end. Rampant development in Tirana was already a problem prior to Erion Veliaj’s election as mayor of the city, and in fact Veliaj insisted during his campaign that he would enact a moratorium on construction34. Thus, the opponents of the National Theater’s destruction were particularly angered by the fact that the plan for the land occupied by the complex as a whole (including property located behind the theater itself) appeared to include the construction of even more high-rise buildings.

The transformation of Tirana’s public space during Erion Veliaj’s time as mayor must also be understood against the longer history of interventions carried out by Veliaj’s close political ally (and former mayor of Tirana from 2000 to 2011), Edi Rama35. Rama, who was elected prime minister of Albania in 2013, is an artist as well as a politician, and his political projects have often had an explicitly aesthetic aspect. The son of one of socialist Albania’s best known (and most privileged) monumental sculptors, Rama began his career as a painter, and left Albania for Paris before eventually returning to take a position as the Albanian Minister of Culture in 1998. Early in his career as mayor of Tirana, he initiated a project that has now become widely known in both the artworld and amongst political commentators: he painted the façades of a large number of socialist-era apartment blocks along the city’s main roads with bright colors36. In 2005, he stated, “[F]or me Tirana is a mirror, an affirmation, a confirmation of my vision, or call it my will, or my person”37. With Rama’s ascent to the position of prime minister, his fusion of art and politics came to encompass the entire country—in a 2014 keynote speech at the Creative Time Summit in Stockholm, Rama explained:

“[I]n politics too, I try to paint a canvas. I visualize how I want our country to be, to feel. […] What does the artist have in mind as he paints a picture? He has in mind a vision of a finished work. So today as the leader of my country, I have a vision in my mind for a country that is more modern”38.

One of the largest recent transformations in Tirana, the construction of a new Skanderbeg Square at the city’s center, was a project first initiated by Rama during his time as mayor of Tirana but ultimately implemented by Veliaj (with Rama’s support) and completed in 201739.

Rama continues to maintain a prominent reputation in the global contemporary art world as an artist-politician—in 2016, the well-known curator Hans Ulrich Obrist introduced Rama to an audience in New York City with the enthusiastic (if naïve) declaration, “In the artworld we talk about artist-run spaces, but it’s very exciting to talk about artist-run countries”40. Given the close association between Rama’s artistic pursuits and his politics, it is hard not to see the transformations in Tirana’s city center—including the new Skanderbeg Square, the destruction of Qemal Stafa Stadium, and the plan to demolish the National Theater—as elements of an aesthetic plan imposed from above, the operation of a centralized artistic taste that is more interested in its own fulfillment than in the operation of public debates about history, memory, and conservation. The cultural capital associated with the contemporary art world has also served to effectively artwash problematic elements of Rama’s policies, since—in the Western media—his role as an artist is enough to secure him the associations of a progressive and fundamentally democratic figure41.

What troubled the Alliance for the Theater, however, was not just the erasure of a building they felt to be an important historical site, nor just the Rama government’s continued aesthetic transformation of the city center (emblematized by the hypothesized construction of several towers on the site). Even more alarming was the public-private partnership that immediately appeared in relation to the construction of the theater, and the legal maneuvers executed to ensure the theater’s destruction. The very same month that the plan to demolish the theater was announced, the private construction company Fusha Ltd. (also the company contracted to construct the new Skanderbeg Square) presented an unsolicited proposal to the municipality of Tirana, proposing the construction of a new theater and several commercial buildings on the site42. In March of 2018, when he officially announced the plan for the new theater designed by Bjarke Ingels Group, Rama explained that the only financially feasible way to construct the theater was through a public-private partnership and that “the project [would] be implemented by means of a special law from the Albanian Parliament”43. This special law would have transferred the land that included the theater complex, as well as pieces of property behind it, directly to Fusha Ltd., effectively expropriating a large section of public land and giving it directly to a private developer. The plan for the new theater, designed by BIG, would occupy approximately 3,000 square meters, while the total property to be transferred to Fusha Ltd. constituted over 7,000 square meters, thus giving the majority of the property to a private company—for its own benefit—in return for the construction of a new theater44. The Rama government could be relatively certain that the law—which many considered unconstitutional—would pass, since many seats in Albania’s Constitutional Court were empty due to justice reforms begun in 2016, and the court lacked the capacity to veto it45. Thus, critics argued that the theater situation represented a problematic state of exception in many aspects: it deepened the privatization of Tirana’s public space, benefiting private developers (and, in the case of BIG’s plan for the new theater, bypassing any public competition for designs)46, and it exploited ongoing justice reforms to covertly create a special law (simultaneously bypassing local government) in order to orchestrate this transfer of property into private hands47.

Rena Rädle and Vladan Jeremić, Paris Commune Revisited/Komuna e Parisit Revisited, 2019.

Transformative action, commissioned by Tirana Art Lab (TAL).

“Monument of Culture, Protected by the People”

The movement to protect the National Theater was not primarily focused on the ideological associations of the building itself, but rather on the modes of operation and obfuscation that its announced destruction set in motion. Although it is impossible to give a detailed chronology of the protests here48, I want to offer an abbreviated account, highlighting some of the different strategies utilized by the protesters in the effort to save the structure: direct physical interventions, physical clashes with police, the occupation of the building, ongoing performances and speeches at the site, communication with international heritage organizations, and the creation of works of art aimed to thematize the struggle over the building.

Over the course of the more than two years of protest, activists were often galvanized by what appeared to be sudden efforts to destroy the building without warning. For example, on the evening of April 26, 2019, the letters spelling out the building’s name (Teatri Kombëtar) on its façade were mysteriously removed, an act that caused immediate speculation that demolition would soon follow. In a symbolic act of restoration, in early May, protesters installed new letters—in the same style and dimensions as the previous ones—on the building. In the course of replacing the letters, the protesters clashed with the private police forces installed at the entrance of the building49. This conflict was but one of many that represented an ongoing push and pull on the part of the government and the protesters: later, in July of the same year, protesters became concerned by the appearance of workers who were apparently removing furniture and other objects from the theater. Worried that this reflected its impending demolition, protesters clashed with the police surrounding the building50; police used tear gas and violence in the conflict, and ejected reporters from the immediate area51. Eventually, the activists successfully occupied the building, and maintained a presence within the theater until the eventual police raid and demolition in the spring of 2020.

A few days after occupying the building, the activists announced the re-opening of the theater, with well-known actor Mehdi Malkaj performing the monodrama I Dare (Marr Guximin) to a full house52. Outside the theater, the regular meetings, performances, and open mic events continued. At some point, the #ProtecttheTheater banner was replaced with a new one, that read “Monument of culture, protected by the people” (“Monument Kulture Mbrohet nga Populli”). Debates persisted—a major earthquake in November of 2019 gave the government a new reason to urge demolition, citing structural damage (although there was no evidence significant damage had occurred)53. While the government continued its efforts to justify demolition, the Alliance for the Theater also had to fend off efforts by the right-wing Democratic Party (currently in the opposition) to co-opt the protests as a political movement and subsume the case of the theater under a general effort to rally support for the opposition party54. Ultimately, differences over the organizational structure the Alliance split the protesters in late 2019, but the two groups would persist in separate efforts to raise awareness about the issue and prevent the demolition55.

Rena Rädle and Vladan Jeremić, Paris Commune Revisited/Komuna e Parisit Revisited, 2019.

Transformative action, commissioned by Tirana Art Lab (TAL).

The cause of the theater became a rallying point not only for performing artists and directors (such as Neritan Liçaj and Robert Budina, two figures who vocally took part in the movement), but also for the broader contemporary art scene in Albania. Several interventions and works of art were created to highlight the issue. On September 11, 2018, visual anthropologists Arba Bekteshi and Kailey Rocker approached the potential destruction of the theater in a different way. Bekteshi and Rocker created three flyers that imitate the format of public death notifications affixed to the walls of buildings and electric posts in specific areas of the city, where citizens learn about the scheduling of memorial services for deceased persons. The flyers that the anthropologists affixed to several walls around Tirana (including the sloping surfaces of the Pyramid) announced the death of three structures—Qemal Stafa Stadium, the Tirana Castle, and the National Theater—and listed the date of the next Parliamentary Debate on the issue of the theater as the date for memorial services.

Rena Rädle and Vladan Jeremić, Paris Commune Revisited/Komuna e Parisit Revisited, 2019.

Transformative action, commissioned by Tirana Art Lab (TAL).

In October of 2019, artists Rena Raedle and Vladan Jeremić carried out a performance, as part of the exhibition Paris Commune Revisited organized by Tirana Art Lab, one of the city’s independent art spaces. As part of the performance, the artists first created a number of flags and cardboard boxes mounted on long handles that could be carried through the streets like protest placards and assembled (both in motion and at the destination) to create different images recalling the visual language commonly used by activist and solidarity movements. On October 12, the artists and a group of citizens carried the flags and boxes from Tirana Art Lab’s exhibition space to the theater building, passing and pausing at several other major historical buildings along the way (such as the Pyramid, built in the late 1980s as a museum dedicated to socialist dictator Enver Hoxha after his death, and the National Gallery of Arts).

Stefano Romano, Zanafilla (the Origin), 2019.

Video, color, sound, 13’00”.

In March of 2020, Italian-born artist and curator Stefano Romano organized an exhibition of work by visual art students from Tirana’s POLIS University inside the National Theater56. Like Malkaj’s performance, this gesture aimed to return the theater complex to regular use, inviting the public (and a younger generation of artists) into the building, and strengthening its symbolic role as a point of solidarity throughout the artistic community. (Romano also created a video entitled The Origin (Zanafilla), partially filmed inside the theater and structured around the recitation of a cadavre exquis poem written by supporters of the movement.)

Stefano Romano, Zanafilla (the Origin), 2019.

Video, color, sound, 13’00”.

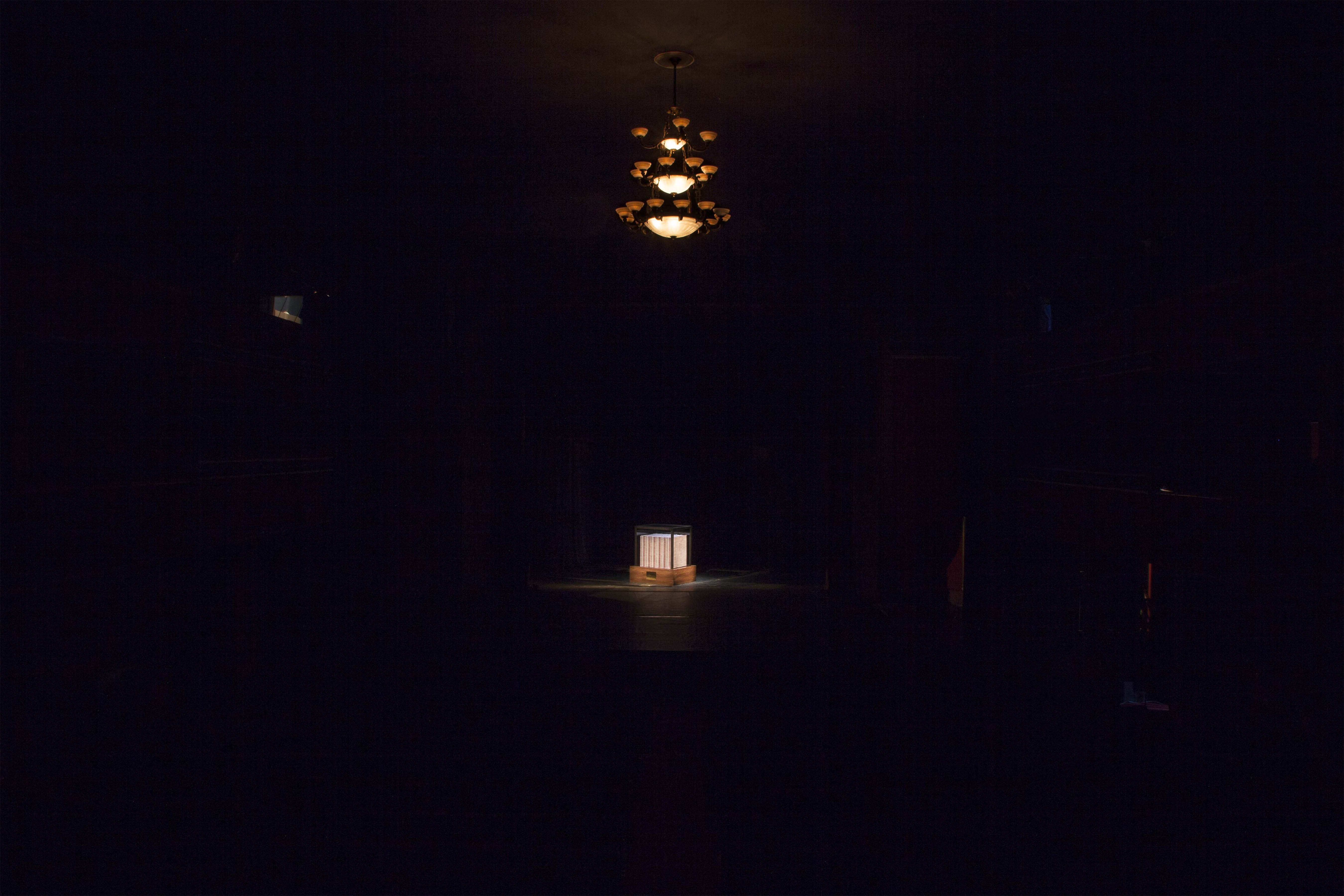

Artist Pleurad Xhafa, a member of the Debatik Center for Contemporary Art, created an installation entitled 200 Million Euro, sited on the stage of the National Theater, in early 2020. Comprised of 500-Euro notes printed on A4 office paper arranged in a cube and protected by a glass case; arranged in six columns, the stacks of fake bills formally recalled the six towers that were projected behind the new theater building57, 200 Million Euro was one of a series of Xhafa’s works investigating of the materiality of government corruption in contemporary Albania (other artworks involved cubes of concrete and marijuana, respectively)—its title alludes to a sum that is repeatedly referenced when rumors of corruption circulate. For example, a 2015 OSCE internal report cited 200 million euro as the amount held in Edi Rama’s offshore accounts. 200 million euro was also the precise amount that Fusha Ltd. was rumored to be profiting from the construction of the new theater and the commercial and residential buildings at the same site. Displayed on the stage of the theater, the work added a museal component to the space, suggesting the beginning of an enduring permanent collection that would be housed within the theater, serving as a record of the relations between the building and the political and economic forces bent on its destruction.

Pleurad Xhafa, 200 Million Euro, 2020.

Installation on the stage of the National Theater, Tirana, Albania. Created with the support of the DebatikCenter for Contemporary Art.

These and other works of art accompanied the ongoing protests, helping contribute to the perceived cultural capital of the protests. In a sense, they showed the solidarity of a large number of artists (from across many fields of activity) banding together to oppose the singular vision of the artist-politician (prime minister Rama). At the same time, the cultural significance of the movement might be most succinctly summarized as a refusal: the refusal to ignore the ongoing, systemic violence of neoliberal capitalist urban development in Albania; the refusal to allow the past and present to succumb to an overly aestheticized vision of postsocialist progress.

The coronavirus pandemic changed the possibilities of the protest, limiting the potential for public engagement and large gatherings. In March, when Europa Nostra included the National Theater on its list of the 7 most endangered heritage sites in Europe, members of the Alliance for the Theater (actor Robert Budina and architect and heritage expert Kreshnik Merxhani) announced the information to a small group gathered at the site, but they were quickly removed by police, under the pretext of the general ban on public gatherings and speeches implemented in response to the pandemic58. In the early months of 2020, the Tirana municipality announced that the new theater would be financed by public funds, and not by Fusha Ltd. (despite the initial claim that the government lacked the funds to construct the theater, creating the necessity for a public-private partnership). In early May, Rama’s government transferred ownership of the land directly from the Ministry of Culture to the municipality, a move of questionable legality but one that avoided the controversies involved in the earlier effort to give the land directly to a private entity59. Later that month, on the morning of May 17, the police stormed the theater to arrest the protesters still occupying the space. Immediately afterwards, excavators began the demolition. Pleurad Xhafa was among the activists occupying the space; 200 Million Euro was destroyed along with the theater building.

Pleurad Xhafa, 200 Million Euro, 2020.

Installation on the stage of the National Theater, Tirana, Albania. Created with the support of the DebatikCenter for Contemporary Art.

The National Theater as Counter-Heritage

And so we return to the darkness of Armando Lulaj’s video, Live, Sunday, May 17, 2020, 4:31AM. As Lulaj notes in his statement about the work, the video’s audio has been developed by a sound engineer who focuses on amplifying audio for its use in criminal court cases. The video, then, is not so much a work of art as it is a piece of evidence: it situates the former theater as the site of a crime, of an illegal exercise in state violence. In the immediate wake of the theater’s demolition, renewed protests broke out, and clashes with police ensued. An open letter—written by cultural theorist Jonida Gashi and publisher and philologist Vincent W.J. van Gerven Oei—circulated, calling on the contemporary artworld to condemn both the theater’s demolition and Rama’s authoritarian politics, long obscured by artwashing60. The open letter was circulated by the Debatik Center (of which Gashi is a member) as part of an effort to galvanize solidarity in the artworld (both local and international) against Rama’s politics, cultural and otherwise. Artists from Debatik Center (including Lulaj and Pleurad Xhafa) had been involved in the protests since early on, but the letter—signed by numerous members of both the local and the international artworld—indeed it represented a key moment, one in which the specific case of the National Theater was framed as part of a broader authoritarian political agenda, against which artists across the world could—and should—take a stand.

Investigation into the matter of the National Theater of Albania’s destruction continues61, and at the time of writing, no construction has taken place at the site. It remains unclear if a new theater will be built, or if the old one will be rebuilt in some way, or if a different fate entirely awaits the plot of land. How can we read the destruction of the theater, the longevity of the protests to protect it, and the complex intertwinement of issues that its impending demolition brought to the surface? Of course, the theater is a paradigmatic example of contested heritage, of the overlapping categories (fascist history, communist history, cultural heritage, postsocialist progress) that can turn a monument into a site of conflict. And indeed, many of the most compelling cases for the theater’s protection named it precisely as heritage. However, I propose to interpret the National Theater’s significance through a slightly different lens, to read it as a form of counter-heritage, a term introduced by architect and historian Andrew Herscher in his discussion of architectural modernization in Prishtina, Kosovo. Herscher explains that although “heritage” is often discursively constructed through a juxtaposition with modernity (with heritage representing a desirable pre-modern legacy that merits preservation alongside the modern), it is also “dialectically related to another category[:] counter-heritage”62. Counter-heritage is that which is excluded from the material and discursive creation of valorized heritage: it is the endemically unmarked category that is destroyed by modernization in order to enable both progress and preservation. What is noteworthy in Herscher’s analysis of counter-heritage is that modernization is “materialized not only by newly constructed modernist architecture, but also by the ruination of condemned, pre-modernist architecture”63. In other words, modernization projects do not simply identify heritage that must be preserved in the context of new construction; they also necessarily and ideologically entail the destruction of certain undesirable elements of urban space. In turn, counter-heritage can serve as a new way of thematizing violence, since it discursively maps the material artifacts and structures that dominant systems must eliminate in order to perpetuate their narratives.

Of course, in the case of the theater, the chronology (pre-modern versus modern) is not entirely accurate: we should instead speak of competing notions of modernization. While in its own time the theater represented a campaign to modernize urban space, in the current context its modernist (and modernizing) characteristics were dismissed by the government, in juxtaposition with current efforts (which of course follow much the same blueprint as previous modernization campaigns). The theater protest, then, thematized current efforts to transform Tirana’s urban space as acts of erasure and violence—it showed what the current Albanian government is actively attempting to exclude from its narrative.

There is, of course, a pessimistic attitude to this analysis: it admits that the theater attains its significance as a historical object in the present and as a catalyst for future action precisely by having been destroyed. It is impossible to know what might have happened if the theater had been spared—but one can imagine it might instead have been turned into an exemplary exception, a case that the current government would hold up to demonstrate its commitment to heritage preservation, even as it would continue to radically alter and destroy other historic elements of Tirana’s center. In any case as an object of destruction, the National Theater has become all the more powerful: it now succinctly illustrates the violence that is endemic to contemporary Albanian urban politics, and indeed to contemporary neoliberalism. Authors have written at length about the forms of violence inherent in neoliberalism, which—with its disavowal of ideology, and its emphasis on individual consumption as opposed to shared social wellbeing—has created new forms of inequity and prolonged social trauma in the present64. As a site of social conflict—most recognizable in the violence used by police in the July 29 clashes with protesters—the theater of course possessed this capacity, but in the wake of its demolition, the theater reflects violence in an explicit and widely recognizable form: as the intentional destruction and erasure of the built environment, along with its communal associations, its memory and its history65.

In the midst of a wave of global activism aimed at dismantling the monumental legacies of colonialism (including the legacies of fascism, and often interpreted as including the material signifiers of the communist past as well, at least in Central and Eastern Europe), it is important to recognize the ways that essentially authoritarian modes of urban restructuring and gentrification can masquerade as efforts to remove unwanted heritage. In the case of the National Theater, a project that appeared—superficially—to remove the undesirable remnants of the fascist colonial period in fact masked a program of urban transformation that benefits private interests and contributes to deepening inequities in Albanian society. By reinforcing the centralization of cultural infrastructure and projecting expensive new housing and commercial opportunities that are, practically speaking, available only to elites—while at the same time expropriating public property to do so—the initial plan for the new National Theater represented the most problematic aspects of neoliberal development in Albania today. Of course, these problems are by no means unique to that country, and that is precisely why the case of the National Theater serves as an illustrative one in a broader context. It demonstrates vibrant efforts to keep alive the memories and histories associated with specific elements of the built environment, through overlapping strategies of community gathering, spatial occupation, and artistic production. It shows that architectural histories are complex, and that communities possess the ability to keep alive the complexities of these histories. It also shows how these activist strategies can be mobilized to shed light on state violence and urban destruction as a persistent aspect of neoliberal urban development. In the face of neoliberalism’s emphasis on growth at the expense of historical consciousness, sometimes the strongest gesture is the one that points to everything that must be demolished in order for that growth to appear as progress.

Notes

1

Armando Lulaj, Live, Sunday, May 17, 2020, 4:31AM, 2021, video, color and sound, 9:45. The video can be viewed at https://debatikcenter.net/archive/national-theatre and https://youtu.be/kmel881-HKk.

2

Unless otherwise indicated, translations from Albanian to English are by the author. Throughout the text, I have translated key quotations and slogans, but included the Albanian in parentheses where it seemed prudent.

3

For an overview of early debates about the plan for the National Theater’s demolition, see the segment of Opinion, hosted by Blendi Fevziu, “A do të shëmbet Teatri Kombetar!?”, TV KLAN, February 14, 2018, as well as Blendi Fevziu, “Erion Veliaj për kullat dhe teatrin!”, TV KLAN, February 22, 2018.

4

“Mes akuzave për korrupsion, sharjeve dhe shtyrjeve: Beteja 2-vjeçare për Teatrin Kombëtar”, ABCNews.al, February 26, 2020.

5

See “National Theatre of Albania, Tirana, Albania”, Europa Nostra, March 24, 2020.

6

For an overview of the National Theater’s history, and its destruction, see Federica Pompejano and Elena Macchioni, “Past, Present, and the Denied Future of Tirana National Theatre”, in Anna Yunitsyna, et al. (eds.), Current Challenges in Architecture and Urbanism in Albania, Cham, Springer, 2021, p. 137-148, and Federica Pompejano and Elena Macchioni, “Tirana National Theatre: Chronicle of an Announced Demolition”, Journal of Architectural Conservation, vol. 28, no. 2, 2022, p. 71-88. See also Rubens Shima, “Teatri Kombëtar, kronika e shembjes së një godine të jashtëzakonshme”, Panorama Online, June 15, 2018.

7

Jean-Baptiste Chastand, “En Albanie, le Théâtre national détruit par le gouvernement, ‘un acte barbare’”, Le Monde, May 25, 2020.

8

For example, Anton Vidokle of e-flux posted on Facebook that the protests “look[ed] more like someone is orchestrating protests to destabilize the current government”. He later deleted the post. I thank Vincent W.J. van Gerven Oei for preserving screenshots of Vidokle’s Facebook post.

10

On the perception of the law, and specifically on public concerns about the lack of transparency in the transfer of the National Theater property, see Gjergji Vurmo, Rovena Sulstarova, and Alban Dafa, Deconstructing State Capture in Albania: An Examination of Grand Corruption Cases and Tailor-Made Laws from 2008 to 2020, Transparency International, 2021, p. 26-28.

11

Andrew Herscher, “Counter-Heritage and Violence”, Future Anterior, vol. 3, no. 2, Winter 2006, p. 24-33.

12

For a more detailed account, see Federica Pompejano and Elena Macchioni, “Past, Present, and the Denied Future of Tirana National Theatre”, in Anna Yunitsyna, et al. (eds.), Current Challenges in Architecture and Urbanism in Albania, Cham, Springer, 2021, p. 139-141.

13

When I refer to the National Theater, I am referring to the northern section of a U-shaped complex. The southern section and the back portion of the complex served different functions (initially the entire building comprised the Circolo, with a theater and cinema located in the northern part). After socialism, the southern portion became the National Experimental Theater Kujtim Spahivogli. The entire complex was demolished in 2020, but the protests focused on the more visible institution, the National Theater housed in the northern section.

14

On the activities of this office, see Anna Bruna Meghini, “La costruzione di Tirana attraverso l’opera dell’Ufficio Centrale per l’Edilizia e l’Urbanistica”, in Anna Bruna Meghini, Frida Pashako, and Marco Stigliano (eds.), Architettura Moderna Italiana per le Città d’Albania: Modelli e Interpretazioni, Bari, Politecnico di Bari, 2012, p. 49-63.

15

Rubens Shima, “Teatri Kombëtar, kronika e shembjes së një godine të jashtëzakonshme”, Panorama Online, June 15, 2018.

16

In fact, Bertè’s role in the transformation of Albania’s urban landscape was relatively underrecognized—in the Albanian context at least—prior to the controversy over the National Theater. Most discussions of Tirana’s urban fabric during the period of Italian alliance and occupation had focused on Brasini, di Fausto, and Bosio. However, at least one study highlighted Bertè’s role not only in Tirana, but elsewhere in Albania: Luciana Posca and Clementina Barucci, Architetti italiani in Albania, 1914-1943, Rome, CLEAR, 2013.

17

Elidor Mëhilli, From Stalin to Mao: Albania and the Socialist World, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 2018, p. 23-29.

18

Romeo Kodra, “Architectural Monumentalism in Transitional Albania”, Studia Ethnologica Croatica, vol. 29, 2017, p. 196-204.

19

It should be noted that one of the cultural mandates of the Circolo “Scanderbeg” was an explicitly ethno-racial one, defined in its founding document as the study “of the brotherly rapport between the Romano-Italian races and the Ilirian races, and the dissemination of these studies in Italy and Albania”. See Rubens Shima, “Teatri Kombëtar, kronika e shembjes së një godine të jashtëzakonshme”, Panorama Online, June 15, 2018.

20

See Artan Raça, “Një ‘rrënojë’ e bukur, një ndërtesë e mrekullueshme: Për Teatrin”, Telegrafi.com, July 3, 2018, and Angela Cecinato and Claudia De Vergilio, “Teatri Kombëtare, Museo della Città di Tirana”, in Anna Bruna Meghini, Frida Pashako, and Marco Stigliano (eds.), Architettura Moderna Italiana per le Città d’Albania: Modelli e Interpretazioni, Bari, Politecnico di Bari, 2012, p. 201-213.

21

Rubens Shima, “Teatri Kombëtar, kronika e shembjes së një godine të jashtëzakonshme”, Panorama Online, June 15, 2018.

22

Federica Pompejano and Elena Macchioni, “Past, Present, and the Denied Future of Tirana National Theatre”, in Anna Yunitsyna, et al. (eds.), Current Challenges in Architecture and Urbanism in Albania, Cham, Springer, 2021, p. 139.

23

As of writing, the Hotel “Dajti” is currently undergoing renovations (after having been closed for some time), and the National Gallery of Arts (recently renamed the National Museum of Fine Arts) has closed for renovations that will include the construction of a new wing. It is difficult to gauge how much these reconstruction efforts will preserve the aesthetic and structural integrity of the current buildings.

24

On the Special Court and the trials, see Çelo Hoxha, “Gjyqi Special: një akt terrorizmi shtetëror”, PostBllok, April 27, 2015.

26

Blendi Fevziu, “Erion Veliaj për kullat dhe teatrin!”, TV KLAN, February 22, 2018. Subsequent quotations from Veliaj in this paragraph are from this same television interview. In the interview, Veliaj cited an edited volume compiled by Italian scholars in 2012, wherein the material of the theater is discussed at length: Anna Bruna Meghini, Frida Pashako, and Marco Stigliano (eds.), Architettura Moderna Italiana per le Città d’Albania: Modelli e Interpretazioni, Bari, Politecnico di Bari, 2012.

27

Angela Cecinato and Claudia De Vergilio, “Teatri Kombëtare, Museo della Città di Tirana”, in Anna Bruna Meghini, Frida Pashako, and Marco Stigliano (eds.), Architettura Moderna Italiana per le Città d’Albania: Modelli e Interpretazioni, Bari, Politecnico di Bari, 2012, p. 209. On the use of Populit as part of the so-called Pater construction system (which allowed for lightweight and inexpensive construction materials to be rapidly prefabricated in Italy without using up resources needed for the war effort), see Anna Bruna Meghini, “Experimental building techniques in the 1930’s: the “Pater” system in the Ex-Circolo Skanderbeg of Tirana”, paper delivered at the 2nd International Balkans Conference on Challenges of Civil Engineering, Tirana, Epoka University, May 23-25, 2013.

28

Rubens Shima, “Teatri Kombëtar, kronika e shembjes së një godine të jashtëzakonshme”, Panorama Online, June 15, 2018. Indeed, in the very same edited volume that Veliaj cited, the building that now serves as the University of Fine Arts is identified as Tirana’s dopolavoro—see Anna Bruna Meghini, Frida Pashako, and Marco Stigliano (eds.), Architettura Moderna Italiana per le Città d’Albania: Modelli e Interpretazioni, Bari, Politecnico di Bari, 2012, p. 175–178.

29

For a detailed chronology of the changing laws establishing the protected zone, see Federica Pompejano and Elena Macchioni, “Past, Present, and the Denied Future of Tirana National Theatre”, in Anna Yunitsyna, et al. (eds.), Current Challenges in Architecture and Urbanism in Albania, Cham, Springer, 2021, p. 141-142.

30

Esmeralda Keta, “KKT i hap rrugë ‘kullëzimit’ pa kriter të qendrës së Tiranës në mungesë të Planit Vendor”, Citizens Channel, May 4, 2021.

31

According to Citizens Channel, the municipality of Tirana awarded an average of one work permit every two days during the year 2020; see Bejli Çaushaj, “Tirana: Një leje ndërtimi çdo 42 orë, kryeqyteti i ndërtimit dhe i ndotjes”, Citizens Channel, November 30, 2021.

32

For a list of towers under construction in 2021—numbering around 12—see “Kullat që po i zënë frymën Tiranës”, Exit.al, August 8, 2021.

33

On the stadium, see Florian Nepravishta, “The Metamorphosis of Gherardo Bosio’s ‘Olympic Stadium’ in Tirana”, in Nilda Valentin (ed.), Albania nel Terzo Millenio: Architettura, Città, Territorio/ Albania in the Third Millennium: Architecture, City, Territory, Rome, Gangemi Editore, 2021, p. 41-46.

34

Blendi Fevziu, “Erion Veliaj për kullat dhe teatrin!”, TV KLAN, February 22, 2018.

35

Alessandro Gallicchio, “Tirana, fabrique inépuisable d’expérimentations urbaines”, Cahiers du CAP, no. 7, 2019, p. 101-136.

36

For a lengthier discussion of Rama’s façade-painting project, see Anca Pusca, “The Aesthetics of Change: Exploring Post-Communist Spaces”, Global Society, vol. 22, no. 3, 2008, p. 377-381.

37

Jane Kramer, “Painting the Town: How Edi Rama Reinvented Urban Politics”, The New Yorker, July 27, 2005.

38

Edi Rama, “Creative Time Keynote”, Creative Time Summit Stockholm, December 12, 2014.

39

On the square and its politics, see Raino Isto, “Monumentality, Counter-monumentality, and Political Authority in Post-socialist Albania”, International Journal for History, Culture, and Modernity, no. 8, 2020, p. 150-187.

40

The quote is taken from a conversation between Obrist, Rama, and artist Rirkrit Tiravanija, on the occasion of a solo show of Rama’s art at Marian Goodman Gallery in New York. A video of the conversation (which took place on November 12, 2016) is available on the Marian Goodman Gallery Facebook page.

41

See, for example, Kate Brown, “The Prime Minister of Albania, Edi Rama, Is Also a Professional Artist. Here’s How He Is Balancing Those Roles During the Coronavirus Pandemic”, Artnet, April 23, 2020.

42

“Projekti i Fusha shpk”, Exit.al, July 20, 2018.

43

Edi Rama, qtd. in “Rama: Teatri Kombëtar pa kullë, por me kullë nuk është mëkat!”, Ora News, March 12, 2018.

44

Vincent WJ van Gerven Oei, “A New Theater Demands New Laws”, Exit.al, March 13, 2018.

45

Alida Karakushi, “The Alliance for the Protection of Theatre Fights to Preserve Albania’s Cultural Heritage”, Global Voices, September 28, 2018. Albania’s president, Ilir Meta, returned the law to Parliament as unconstitutional, but the president lacks the ability to definitively overrule the parliament, which was controlled by the Socialist Party (led by Rama).

46

In order to placate those opposed to the destruction, in 2018 the government announced the transferal of the National Theater’s functions to a new space, ArTurbina, a theater constructed in the former Hydrological Laboratory, but many were dissatisfied with the new building. See “Artistët kundër ligjit/ Ndrenika: Fjala që i thashë ministreshës paska qenë me vend...”, Ora News, February 8, 2018.

47

On the ongoing, undeclared state of exception in Albania, see Jonida Gashi, “Trajtat e një gjendje të jashtëzakonshme të pashpallur”, Reporter.al, March 9, 2019.

48

Two detailed timelines of the activities of the Alliance for the Theater can be found in Entela Bineri, “Dritëhijet e Teatrit Kombëtar në Tiranë”, Stopfake.al, November 23, 2020; and the Alliance for the Restoration of Cultural Heritage (ARCH), available at https://www.archinternational.org/2020/08/11/teatri-kombetar-national-theater/.

49

“Vendosen gërmat te Teatri Kombëtar, përplasje mes ish- deputetes së PD dhe policisë private”, Shqiptarja.com, May 7, 2019.

50

“Teatri Kombëtar drejt Shembjes, Artistët Zaptojnë Sallat”, Historia Ime, July 24, 2019.

51

Alice Taylor, “Police Retreat From National Theatre After Tear Gas Fails to Deter Protestors”, Exit.al, July 24, 2019.

52

“Mehdi Malkaj ngjit në skenën e Teatrit ‘Marr guximin,’ autori i veprës: Turp të kesh, godina të shembet”, Shqiptarja.com, July 27, 2019. The author of the drama, Vangjel Kozma, published a statement decrying the performance of the play in the service—her perceived—of a political cause.

53

Kreshnik Merxhani, “Flet arkitekti i njohur”, Standard, May 28, 2020.

54

Alida Karakushi, “Threatened with demolition, Albania's National Theatre continues to resist despite a police raid”, Global Voices, July 29, 2019.

55

Entela Bineri, “Dritëhijet e Teatrit Kombëtar në Tiranë”, Stopfake.al, November 23, 2020.

56

Elira Kadriu, “Ekspozita e studentëve kthen godinën e Teatrit Kombëtar në galeri arti”, Citizens Channel, March 9, 2020.

57

Pleurad Xhafa and Raino Isto, “One on One: 200 Million Euro”, ARTMargins Online, May 13, 2020.

58

“Teatri Kombëtar monument në rrezik, Robert Budina dhe Kreshnik Merxhani shoqërohen në polici”, Shekulli, March 24, 2020.

59

Alice Taylor, “Albanian Government Hands Ownership of National Theatre Land to Municipality of Tirana”, Exit.al, May 9, 2020.

60

Valentina Di Liscia, “Open Letter Condemns the ‘Artwashing’ of Albanian Prime Minister’s Politics”, Hyperallergic, May 19, 2020.

61

Some members of the Alliance for the Theater have persisted in their efforts, putting pressure on the Albanian president, helping to bring the case before the Constitutional Court, which ruled the transfer of the theater property to the municipality as unconstitutional. Edmond Hoxhaj, “Gjykata Kushtetuese rrëzon qeverinë për shembjen e Teatrit Kombëtar”, Reporter.al, July 2, 2021.

62

Andrew Herscher, “Counter-Heritage and Violence”, Future Anterior, vol. 3, no. 2, Winter 2006, p. 25.

63

Andrew Herscher, “Counter-Heritage and Violence”, Future Anterior, vol. 3, no. 2, Winter 2006, p. 28.

64

For two different approaches to violence under neoliberalism, see Simon Springer, Violent Neoliberalism: Development, Discourse, and Dispossession in Cambodia, New York, Palgrave MacMillan, 2015, and Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism, Durham, Duke University Press, 2011.

65

Robert Bevan, The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War, London, Reaktion, 2006.

Bibliographie

“Artistët kundër ligjit/ Ndrenika: Fjala që i thashë ministreshës paska qenë me vend...”, Ora News, February 8, 2018.

Lauren Berlant, Cruel Optimism, Durham, Duke University Press, 2011.

Robert Bevan, The Destruction of Memory: Architecture at War, London, Reaktion, 2006.

Entela Bineri, “Dritëhijet e Teatrit Kombëtar në Tiranë”, Stopfake.al, November 23, 2020.

“Bujar Asqeriu: Teatri është i kalbur, aty gjen minj, bubuzhela, mace, lloj-lloj insekti. Por Rama na fyeu, s’na pyeti fare”, Gazeta Tema, March 20, 2018.

Bejli Çaushaj, “Tirana: Një leje ndërtimi çdo 42 orë, kryeqyteti i ndërtimit dhe i ndotjes”, Citizens Channel, November 30, 2021.

Kate Brown, “The Prime Minister of Albania, Edi Rama, Is Also a Professional Artist. Here’s How He Is Balancing Those Roles During the Coronavirus Pandemic”, Artnet, April 23, 2020.

Angela Cecinato and Claudia De Vergilio, “Teatri Kombëtare, Museo della Città di Tirana”, in Anna Bruna Meghini, Frida Pashako, and Marco Stigliano (eds.), Architettura Moderna Italiana per le Città d’Albania: Modelli e Interpretazioni, Bari, Politecnico di Bari, 2012, p. 201-213.

Jean-Baptiste Chastand, “En Albanie, le Théâtre national détruit par le gouvernement, ‘un acte barbare’”, Le Monde, May 25, 2020.

Blendi Fevziu, “A do të shëmbet Teatri Kombetar!?”, TV KLAN, February 14, 2018.

Blendi Fevziu, “Erion Veliaj për kullat dhe teatrin!”, TV KLAN, February 22, 2018.

Alessandro Gallicchio, “Tirana, fabrique inépuisable d’expérimentations urbaines”, Cahiers du CAP, no. 7, 2019, p. 101-136.

Jonida Gashi, “Trajtat e një gjendje të jashtëzakonshme të pashpallur”, Reporter.al, March 9, 2019.

Vincent WJ van Gerven Oei, “A New Theater Demands New Laws”, Exit.al, March 13, 2018.

Andrew Herscher, “Counter-Heritage and Violence”, Future Anterior, vol. 3, no. 2, Winter 2006, p. 24-33.

Çelo Hoxha, “Gjyqi Special: një akt terrorizmi shtetëror”, PostBllok, April 27, 2015.

Edmond Hoxhaj, “Gjykata Kushtetuese rrëzon qeverinë për shembjen e Teatrit Kombëtar”, Reporter.al, July 2, 2021.

Raino Isto, “Monumentality, Counter-monumentality, and Political Authority in Post-socialist Albania”, International Journal for History, Culture, and Modernity, no. 8, 2020, p. 150-187.

Elira Kadriu, “Ekspozita e studentëve kthen godinën e Teatrit Kombëtar në galeri arti”, Citizens Channel, March 9, 2020.

Alida Karakushi, “The Alliance for the Protection of Theatre Fights to Preserve Albania’s Cultural Heritage”, Global Voices, September 28, 2018.

Alida Karakushi, “Threatened with demolition, Albania's National Theatre continues to resist despite a police raid”, Global Voices, July 29, 2019.

Esmeralda Keta, “KKT i hap rrugë ‘kullëzimit’ pa kriter të qendrës së Tiranës në mungesë të Planit Vendor”, Citizens Channel, May 4, 2021.

Romeo Kodra, “Architectural Monumentalism in Transitional Albania”, Studia Ethnologica Croatica, vol. 29, 2017, p. 196-204.

Jane Kramer, “Painting the Town: How Edi Rama Reinvented Urban Politics,” The New Yorker, July 27, 2005.

“Kullat që po i zënë frymën Tiranës”, Exit.al, August 8, 2021.

“Law on National Theater: Parliamentary Committee Refuses Presidential Decree; Law Passes to Parliament for Voting”, Exit.al, October 25, 2018.

Valentina Di Liscia, “Open Letter Condemns the ‘Artwashing’ of Albanian Prime Minister’s Politics”, Hyperallergic, May 19, 2020.

Anna Bruna Meghini, “Experimental building techniques in the 1930’s: the “Pater” system in the Ex-Circolo Skanderbeg of Tirana”, paper delivered at the 2nd International Balkans Conference on Challenges of Civil Engineering, Tirana, Epoka University, May 23-25, 2013.

Anna Bruna Meghini, “La costruzione di Tirana attraverso l’opera dell’Ufficio Centrale per l’Edilizia e l’Urbanistica”, in Anna Bruna Meghini, Frida Pashako, and Marco Stigliano (eds.), Architettura Moderna Italiana per le Città d’Albania: Modelli e Interpretazioni, Bari, Politecnico di Bari, 2012, p. 49-63.

“Mehdi Malkaj ngjit në skenën e Teatrit ‘Marr guximin,’ autori i veprës: Turp të kesh, godina të shembet”, Shqiptarja.com, July 27, 2019.

Elidor Mëhilli, From Stalin to Mao: Albania and the Socialist World, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 2018.

Kreshnik Merxhani, “Flet arkitekti i njohur”, Standard, May 28, 2020.

“Mes akuzave për korrupsion, sharjeve dhe shtyrjeve: Beteja 2-vjeçare për Teatrin Kombëtar”, ABCNews.al, February 26, 2020.

“National Theatre of Albania, Tirana, Albania”, Europa Nostra, March 24, 2020.

Florian Nepravishta, “The Metamorphosis of Gherardo Bosio’s ‘Olympic Stadium’ in Tirana”, in Nilda Valentin (ed.), Albania nel Terzo Millenio: Architettura, Città, Territorio/Albania in the Third Millennium: Architecture, City, Territory, Rome, Gangemi Editore, 2021, p. 41-46.

Federica Pompejano and Elena Macchioni, “Past, Present, and the Denied Future of Tirana National Theatre”, in Anna Yunitsyna, et al. (eds.), Current Challenges in Architecture and Urbanism in Albania, Cham, Springer, 2021, p. 137-148.

Federica Pompejano and Elena Macchioni, “Tirana National Theatre: Chronicle of an Announced Demolition”, Journal of Architectural Conservation, vol. 28, no. 2, 2022, p. 71-88.

Luciana Posca and Clementina Barucci, Architetti italiani in Albania, 1914-1943, Rome, CLEAR, 2013.

“Projekti i Fusha shpk”, Exit.al, July 20, 2018.

Anca Pusca, “The Aesthetics of Change: Exploring Post-Communist Spaces”, Global Society, vol. 22, no. 3, 2008, p. 377-381.

Artan Raça, “Një ‘rrënojë’ e bukur, një ndërtesë e mrekullueshme: Për Teatrin”, Telegrafi.com, July 3, 2018.

Edi Rama, “Creative Time Keynote”, Creative Time Summit Stockholm, December 12, 2014.

“Rama: Teatri Kombëtar pa kullë, por me kullë nuk është mëkat!”, Ora News, March 12, 2018.

Rubens Shima, “Teatri Kombëtar, kronika e shembjes së një godine të jashtëzakonshme”, Panorama Online, June 15, 2018.

Simon Springer, Violent Neoliberalism: Development, Discourse, and Dispossession in Cambodia, New York, Palgrave MacMillan, 2015.

Alice Taylor, “Albanian Government Hands Ownership of National Theatre Land to Municipality of Tirana”, Exit.al, May 9, 2020.

Alice Taylor, “Police Retreat From National Theatre After Tear Gas Fails to Deter Protestors”, Exit.al, July 24, 2019.

“Teatri Kombëtar drejt Shembjes, Artistët Zaptojnë Sallat”, Historia Ime, July 24, 2019.

“Teatri Kombëtar monument në rrezik, Robert Budina dhe Kreshnik Merxhani shoqërohen në polici”, Shekulli, March 24, 2020.

“Vendosen gërmat te Teatri Kombëtar, përplasje mes ish- deputetes së PD dhe policisë private”, Shqiptarja.com, May 7, 2019.

Gjergji Vurmo, Rovena Sulstarova, and Alban Dafa, Deconstructing State Capture in Albania: An Examination of Grand Corruption Cases and Tailor-Made Laws from 2008 to 2020, Transparency International, 2021.

Pleurad Xhafa and Raino Isto, “One on One: 200 Million Euro”, ARTMargins Online, May 13, 2020.