In their war memories, the Soviet officers and soldiers who defended Sevastopol in 1941-1942 often evoke the figure of Nina Onilova, a textile factory worker who volunteered at the very beginning of the war and first served as a nurse before learning to shoot a machine gun. She became famous among them under the nickname “Anka the Machine- Gunner” (Anka-Pulemëchitsa), in reference to one of the most well-known Soviet films of the 1930s, Chapaev, by the Vassiliev brothers. Her method, as reported by her former fighter friends, was in fact close to that of the heroine of the film: let the enemy advance as close as possible, and shoot the latest possible to kill the most possible1.

Chapaev (movie, 1934).

Did the film influence these Soviet veterans to the point where they tacked images from Chapayev onto their war memories? Or on the contrary, was it the film, which came out in 1934, that inspired Nina Onilova’s action when she found herself behind a machine gun? In any case, her story gives us perspective on the question of women and war in the Soviet Union.

Nina Onilova was one of the 800,000 women who served in the Red Army between 1941 and 19452. Although all the Allies recruited women during the Second World War, the USSR was exceptional in that it was the only country to specifically train women in combat functions (aviation, infantry, snipers). A few women had already enlisted during the First World War, and the Tsarist army had accepted the creation of a women’s battalion under the direction of Maria Bochkareva3. During the Civil War, there were many women in the ranks of what would later become the Red Army. In the 1930s, the USSR prepared for a war considered unavoidable and young women, like young men, were recruited to learn how to fly planes, to parachute and shoot guns4. This figure of the female Red soldier was then portrayed in literature and film. In a 1934 novel, Vassili Grossman portrays Commissar Klavdia Vavilova, who leaves behind a newborn son to return to the battlefield5. The same year, in Chapayev, the Vassiliev brothers created the fictional character Anka the Machine-Gunner , inspired by the many female volunteers in the armed groups of the time6.

The film, and especially the combat scene against the White Army shown in the above document, also highlights the ambiguities of women’s access to arms and combat. The growing mechanization of armies, the disappearance of physical strength as a determining criterion for battle, made it possible to imagine a place for women. In the film, Anna shows perfect mastery of her weapon, an excellent sense of tactics and a good dose of cold-bloodedness. Despite that, Anna is not a combatant like the others: she only gets to shoot by default – because the soldier in charge of the machine gun is wounded. Her male comrades make fun of her and express doubts as to her competence, and in the end, it is the men, Chapayev and his cavalry – welcomed by an ecstatic Anna – who force the Whites to flee.

Thus the film suggests that despite the fact that women are capable of using arms, their access to them is an exception, a parenthesis, and that they rank only second as fighters, soldiers by default. Thus once again we find the ambiguity and the questions (status, capacities, recognition by the group) that arise in a more general manner in Western countries vis-à-vis women’s access to the army. The following study of various aspects of the experience of Soviet women in the Red Army between 1941-1945 will show how their experience and the problems that come up coincide with the questions posed more generally in the study of relationships between women and war.

It is not our intention to draw a complete picture of the different ways in which women are affected by war and mobilized by the State7, but rather to study only one of these aspects: women in the army and on the battlefield. More than these women’s experiences, for which sources are fragmentary and marked by the way they were collected8, what interests us here is the State’s mobilization policy and how it recruits, integrates, then demobilizes women. Not only because numerous sources exist9, but also because it is here that the comparative aspect is most evident: the issues faced by Soviet institutions are not very different from those of European states or of the United States when recruiting women in the XXth and XXIst centuries. Examples and analyses from other contexts help gain insight into the Soviet case, in the hope that the Soviet experience will in turn give rise to more general conclusions.

The fact that despite geographic and historical diversity certain parallels can be drawn concerning policies towards women in wartime suggests that the gender aspect constitutes a very relevant entry point. Thus we will “study conflicts as a space for the formation, reproduction and/or transformation of social sex relations”10 to “seize what the conduct of war reveals of the feminine condition and gender relations” but also at the same time to examine “what the study of women fighters teaches us about conflicts”11.

The article follows the different stages, from the entry into war to the post-conflict period, and points out first that the recruitment of women most often obeys a rationale of replacement of men. The integration of women in the military institution also raises the question of its adaptations and management of male-female relations. The experience of Soviet women under fire allows us to place in context debates over physical strength and women’s access to combat. Finally, the post-war period seems to constitute a painful experience for women fighters everywhere, most often confronted with a brutal return to the sexual division of work and a rewriting of their role during the war.

Mobilizing women to replace men

In “The Dawns Here are Quiet”12, the Soviet writer Boris Vasiliev describes an anti-aircraft battery officer, Fedor Vaskov, based in a small village in the North of Russia. Many women remaining alone in the village, Vaskov has a hard time disciplining his men and continually requests his superiors to send him soldiers who don’t drink and aren’t interested in women. “Eunuchs, or what?” asks the major, who finally sends him the support requested: a battalion made up exclusively of women.

The Dawns Here are Quiet (movie, S. Rostockii, part 1, 1972).

The Dawns Here are Quiet (movie, S. Rostockii, part 2, 1972).

In this way, the beginning of the book suggests that when men are no longer able to ensure their role as defenders, women are recruited. This situation can be observed in the USSR as well as in other war contexts: women are most often recruited to replace men. Even in the case of volunteers, such recruitment does not take place without tensions. Which women replace which men, and for which functions?

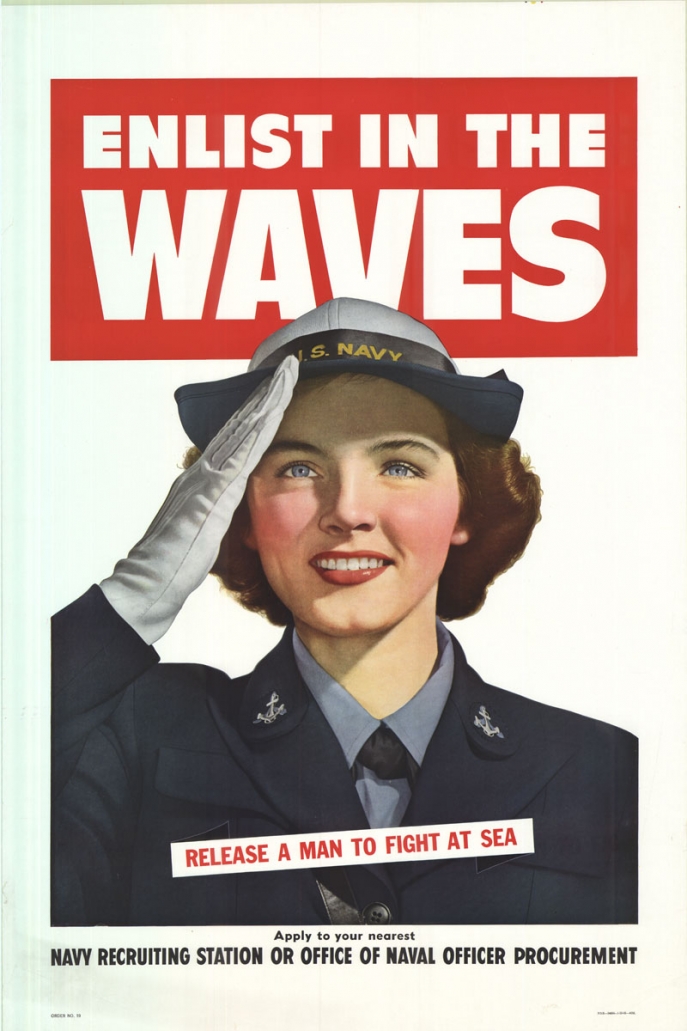

Women are mobilized first of all in factories and on the work front. In France, from the beginning of the First World War, René Viviani, President of the Council of Ministers, called on the wives of farmers to replace men in order to ensure the harvesting of crops13. In the USSR, five days after the German invasion, the 26 June 1941 issue of Pravda headlined: “Wives, sisters and daughters are replacing their husbands, brothers and fathers in factories and kolkhozes”14. The call to replace men appeared on Soviet posters as it did on American posters, prompting women to take over the jobs left behind by the men.

Soviet and American War Posters (1941-1943).

Women were also called on to join the auxiliary corps of the American army to “free a man for combat”, in the same way as in France. As of 1942 the creation of the Free French Women Corps answered to the need to recruit women, so as to “reserve fire” to a maximum number of men15.

Mobilization in the USSR took place according to the same rationale. Although a few women enlisted as of 1941, recruitment policy only really began in the spring of 1942 – to compensate for the enormous losses of the beginning of the war. The State Defense Committee (GKO) adopted a series of measures aiming to replace men by women in non-combatant functions, so as to be able to send men to the front. On 25 March 1942, the decree on “the mobilization of young Komsomol women in anti-aircraft defense units” specifies that it is necessary to “use the soldiers thus liberated, after their replacement by young Komsomol women to complete infantry divisions and brigades”16. That order was followed on April 18 by decree 1618 “on the replacement of men by women in support units and military air force institutions”17.

The recruitment of women in the army in place of men is therefore part of a decision and arbitration process between the different emergency posts of total war (production, police, domestic defense, armed operations) – and can furthermore cause tensions between various demands. When in February 1943 the Soviet government was planning the creation of several female infantry brigades (a project that was abandoned in the end), it specified that “women working directly in production in the defense industry cannot be recruited”18. In charge of implementing the project, the Komsomol moreover warned that “the mobilization of 162,000 women at present encounters great difficulty due to the lack of manpower in the kolkhozes and in industry”19.

Another necessary arbitration is deciding which priority of function should be attributed to women in the army. In addition to supplies (kitchen, bathrooms, laundry), secretariat and transmission (radio, phone operators), health and anti-aircraft seem specifically reserved for women in the USSR as in other Western countries. As of World War I, nurses were present on various fronts, and the military institution was faced with the issue of taking charge of these services, most often dependent on charitable or private initiatives. In the USSR, women and men doctors were mobilized alike as of June 1941, the first women who volunteered at the beginning of the war were proposed service as nurses, and during the conflict, it was women who were sought for training as nurses or auxiliary nurses by the Soviet Red Cross. According to 1943 Red Cross reports, 201,000 women were trained as reserve nurses in a year and a half of war and 290,000 women as rescue workers (sanitarnye druzhinitsy), but only 25,500 men (sanitary)20.

In anti-aircraft defense, where women were mobilized in priority, the USSR was not an exception either. In Great Britain, women began to serve in anti-aircraft batteries as of 1941: a typical battery was composed of 189 men and 299 women, even if only the men were allowed to shoot21. In fact, “countries had tended to see anti-aircraft duties as a natural entry-point for women into the military, for an enemy air attack, by its very nature, would have already been bringing war to the women and children of the country being defended”22. This then was a response to a new kind of war, to the danger of aerial bombing that turned the heart of cities, previously out of reach, into potential targets. In the USSR, committees of Party women already in 1929 were urged to train peasants and workers in civil defense “since in the war to come, these women would above all be in charge of organizing defense against chemical attacks”23.

It remains nonetheless that all women were not considered eligible for recruitment. In Great Britain, whereas the National Service Act made service in the army or military industry obligatory, married women were exempt from recruitment. In the USSR as well, in 1943, “the Central Komsomol Committee prohibited the recruitment of women with dependent children and parents unable to work, and pregnant women”24. The same was true among Free French Forces, where the decree of 29 January 1944 concerning the call for women’s auxiliary military training specified that “the call for volunteers could only concern single women, widows or divorced and without children, aged 18 to 45”25. Thus, in all cases, the States established priorities – fixing the first role of women that of taking care of their family and ensuring the reproduction of the nation.

In fact, the gender issue was not the only one at play when it came to the mobilization of women. Several other factors were taken into account, among them education level (the use of anti-aircraft weapons required a minimum level of education that the sole recruitment of men might not have satisfied), and age. Unlike Nazi Germany, in 1944 the USSR preferred to recruit women rather than men of younger or older classes. A note addressed to Marshal Voroshilov on March 17, 1944 rejects the idea of recruiting seventeen-year-old men, “because they are not physically strong enough, and military service demands a great deal of physical effort, which risks causing deficiencies and delayed development”26.

The matter of soldiers’ ethnic/national origin also played a role. In an article questioning the importance of gender as a discriminatory category in the Red Army, Catherine Merridale points out that for Russian soldiers, a young Russian woman could seem closer than a man from the Ouzbek mountains27. In fact, in 1942, Efim Schadenko, Chief of Staff in charge of recruitment matters, sent a report to Stalin in which he recommended a better use of men from Central Asia and the Caucuses. Recognizing that for officers, the “best contingents” were men “under 35, Russian, Ukrainian, or Bielorussian, 25% Party or Komsomol members, with a good education, etc,” he estimated nonetheless that recruits from Central Asia and the Caucasus “can and absolutely must be used for supplies functions, in economic and service positions, guards of barracks, aerodromes, depots, etc.”28.

This document of course echoes questions that arose in Western democracies during the First and Second World Wars involving colonial, native minorities, or black American troops. As mentioned by Cynthia Enloe, in the United States “women were recruited into the military force only when the recruitment of men from usually marginalized ethnic or racial groups wouldn’t satisfy the generals’ and admirals’ manpower needs”29. In the Soviet case, these discussions on the use of men from Central Asia or the Caucasus and on the mobilization of women were going on at the same time. Men of these nationalities were considered “second rank” fighters, called up to be used, like the only female infantry regiment ever created30, in maintenance or order and supplies corps rather than combat.

Managing women soldiers

The writer Boris Lavrenyov described in his 1924 novel The Forty-first, described how Mariutka, a future machine-gunner, enlisted in the Red Army during the Civil War:

When they announced, in the towns and the country, the recruitment of volunteers for what was still at the time the Red Guard, Mariutka planted her fish knife in the bench, got up in her stiff pants and went off to register among the Red Guards. At first they sent her away, then, seeing that she had the firm intention of returning every day, they joked and accepted her as a Red Guard, with the same rights as the others, but they made her sign a paper renouncing a ‘woman-y’ way of life and among others, having a child, until the final victory of labor over capital31.

The extract clearly shows the issues that face any armed group integrating women: “how to adapt its organization to the needs of ‘those women’ and how to manage relations between men and women, in order, among others, to avoid pregnancies”.

Thus, the integration of women beginning in 1942 required adaptations on the part of the Red Army, reflecting the fact that gender was a blind point in an almost totally masculine institution. In Russian, as in all languages marking a difference between the masculine and the feminine, the question arose, for example, concerning grades and military formulas. Experimentation is quite visible in World War II Soviet documents. The forms used by officers and doctors were pre-filled out in the masculine; in some cases, particularly for grades, the masculine form was kept, and in others it was crossed out, or a feminine ending was added to verbs and adjectives. Thus the mention of the sniper Alexsandra Shliakhova in the Order of the Red Flag on January 31st 1944 is written in the masculine form “The Sergeant Shliakhova32 is decorated (masculine verb ending) by the Order of the Red Flag for exemplary execution of a military mission”33, but a January 1944 medical certificate reads that “she was wounded (feminine verb ending) in combat, authorized (feminine verb ending) to leave the hospital to recuperate”34. Alexsandra Shliakhova was killed on October 6, 1944 and even the inscription on her tombstone reads in a mix of masculine and feminine: “Here lies buried the famous sniper, chief officer of the Guard, Shliakhova, Aleksandra Nicolaevna […] She fell heroically in battles for the Soviet Homeland”35 (masculine forms throughout, with the exception of “she”).

Even when the feminine form exists in Russian (lëchik-lëchitsa, aviator, aviatrice, for example), military language preferred to speak of “woman-aviator”, “women soldiers”, or “woman-sniper” (zhenshina-boets, zhenshina-sniper) without ever feminizing the terms36. The difficulty of recognizing women as soldiers in their own right is compounded by an unwillingness to address them in accordance with their grade. A woman doctor thus recalls her arrival at the front:

The next question was to know how I should be addressed. Comrade Lieutenant? But I was only a small young girl. Lidia Alekseevna? That wouldn’t do, either. Finally they decided to give me the title of doctor Lida. And everyone in the regiment called me only that – doctor Lida37.

The matter of the name arose for “doctoresse Lida” after that of the ill-fitting uniform, because “the jacket reached to my knees and the boots were so big I couldn’t walk in them”. Innumerable testimonies exist, moreover, on ill-fitting uniforms, too large pants, jackets reaching the calf of the leg. Skirts, when they were delivered, hardly allowed one to run or crawl in the mud or snow; it was only as an experiment that women in the female infantry brigade of Moscow had special trousers delivered, with a strip of detachable cloth between the legs in the place of a fly38. As for underwear, that too was masculine, “long underwear with ties, white shirts with ties – a feminine uniform just wasn’t thought of”, a former military nurse explains39.

“We didn’t have sanitary pads either”, recalls a former woman soldier in transmissions, “we’d find a rag somewhere and use it for a sanitary pad”40. That problem also arose for women during the war: “It was very hard when you had your period. No strips, no place to wash. The girls told the division’s Komsomol and he proposed that the sanitary instructor deliver as much cotton and strips of cloth as we needed”41.

Thus the presence of women obliged the military institution, with more or less diligence and reticence, to make certain adaptations: sanitary pads42, underwear, uniforms adapted to women’s physiology43, separate baths, gynecological consultations, etc. Some of these adaptations were made, case by case on the ground, others were centrally decided: thus the August 1942 decree authorized delivering to women who didn’t smoke 200 grams of chocolate or 300 grams of sweets per month instead of tobacco44; an April 1943 decree provided for the distribution to women of 100 grams more soap45. It is difficult however to know whether these decisions issued from the representations and stereotypes of the decision-makers or from requests actually formulated by the women.

The military institution also deemed it necessary to address the question of relations between men and women, sexual relations in particular, obviously a military as well as a health preoccupation: to avoid pregnancies and/or venereal diseases and ensure that women recruits remain able to serve. The historian Oleg Budnitski notes indeed that some women enrolled in the Red Army sought to become pregnant, as an opportunity to leave the army, even if the conditions of their service (until the seventh month of pregnancy) were particularly difficult46. But there was also a significant moral aspect, that of regulating sentimental and sexual relations between men and women and preventing relations outside of marriage or cases of adultery.

The intervention of the politico-military authorities in the relations between men and women in an armed group is a constant, whatever the context, both in institutionalized armies and in armed rebellions. The solutions adopted vary between two poles: the simple prohibition of sexual relations (as is the case in the PKK in Kurdistan, or the FARC in Colombia), or the organization of these relations under strict control. Thus in the Huk rebellion in the Philippines, men (and men only) could, because of their “physiological needs”, ask to take a second “forest wife” for the time they were in the bush, on condition that their official wife be aware of it and that they do not remain bigamous after the end of the war47. Between these two poles, a whole range of measures or practical arrangements existed, such as giving women the role of officer to avoid their fraternizing with men (as in the British and Canadian armies during the First World War)48.

In the USSR during World War II, the question was raised by different institutions without finding a single solution for all cases. Whereas cohabitation and extra-marital relations developed rapidly in the Red Army, the Komsomol sought to oppose this by valorizing purity and the absence of sexual relations in “young girls”. Some representatives of the Party or of the army thought it preferable to turn a blind eye to it49. In any case, these cohabitation practices were common enough for the term “field wife” (pokhodno-polevaia zhena or PPZh) to be adopted (by analogy with the machine-gunner PPSh). It is difficult to dissociate this question from that of sexual harassment, when we know that the vast majority of men with “field wives” were officers and the women (radio-telegraph operators, nurses) their subordinates.

Even if the issue of acts of sexual violence committed by the Red Army is one that has been approached by researchers50, testimonies on harassment in the army itself remain rather rare51. Women prefer to underline that it didn’t take place “in their unit”, in that way bringing to light the importance of commanders of intermediate levels, whose behavior and discourse could encourage or on the contrary, discourage such practices52.

During the war itself, women were aware of this phenomenon and talked about it. The sniper Polina Galanina testified to the Academy of Sciences Commission:

In fact, men do harass us. We had a section head, Dugman, who tried to get what he wanted by giving me orders. But I informed him that in that case, we were equals, even though I was only a caporal and he a lieutenant. He summoned me to his barrack. At first his secretary and a sergeant were there. Then they left. I made my report, and he began feeling me up. I pushed him off, he fell, got furious, and started all over again. I screamed, a patrol came and opened the door. [After a second try] I told our Party representative first. They summoned him and gave him five days arrest53.

Women thus try to mobilize various resources (military regulations, Party or Komsomol representatives), and up to the highest authorities. On 21 February 1944, for example, Staff Sergeant Nata Netiazhuk wrote to Komsomol officials reproaching them with their inaction in face of “these revolting facts, when commanders, from the lowest to the highest grade, seduce young birds, and then treat them with disdain and send those they have ruined to the back. I have observed this myself in three sectors of the front”54.

However, the capacity for reaction of these women is limited in two ways. First of all, because they are almost always in a subordinate position: women rarely go beyond the grade of non-commissioned officer, and there are practically no women among field officers55. But also because of the moralizing position adopted by the Party and especially by the Komsomol, which puts the blame for harassment on women. In January 1944, the Komsomol Central Committee made a series of recommendations on the measures partisans must take concerning the women in their groups. Two consecutive recommendations were formulated as follows:

10 – Change radically one’s attitude towards young women. Put an end to cases of forced cohabitation […]

11 – Young women in partisan detachments must not, by their behavior, provide a pretext for improper behavior on the part of men (and in that way undermine the authority of all young women)56.

Waging war – beyond the question of combat

In this same document, the Komsomol formulates a certain number of other recommendations, drawn from an inquiry among women partisans. These recommendations suggest that women should have the same access to combat as men, and be recognized for it:

Organize the military training of young women: a) Every young woman must master first aid b) Master all types of arms available in the unit, so that at any moment she can act on the battlefield without masculine aid […] Unit commanders must insofar as possible arm young women in equality with young men […] Young women who have distinguished themselves in combat, in the derailing of trains, etc. must be presented in the same way as men for government decorations57.

This document is both the reflection of the aspirations of women (who represent approximately 10% of partisans according to official figures) and of the difficulties they face on the terrain where, as Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau writes, “the gender barrier is never harder to penetrate than when it is a matter of access to combat”58.

Whatever the context, and still today, women who desire access to combat functions are confronted with two types of argument: the need to maintain the operational cohesion of the group, which can be weakened by the presence of women59, and their lesser physical strength. Researchers opposed to women’s access to combat emphasize that when equal in height, they have only 80% of a man’s physical strength60, and that morphologically, the strength of the upper part of their body will always be less. The Soviet case brings to light the contradictions and what lies unsaid beneath this discussion of physical strength, but it also demonstrates the fragility of the distinction between combatant and non-combatant, as evidenced by the multiplicity of activities involved in being “under fire”.

The question of physical strength was raised in the USSR during the war, and first of all by the women themselves. Thus one partisan speaking at a meeting in Moscow found it important to emphasize that:

In the execution of combat missions, women are no less capable than guys, they are even more resistant. Often, in marches, the guys get so tired that the girls even have to carry their weapon and their affairs61.

The military institution also took that question into account – but on the assumption that women were less strong to begin with. When the Moscow Women’s Volunteer Infantry Brigade was created, they planned for more women soldiers than men serving each arm.

2- a) for an anti-tank gun – increase to three the average of 2.5 men b) for a 76mm gun increase to 10 instead of 7 men c) for a 45mm gun 8 instead of 7 d) for trucks – 2 drivers

3- Additionally, in the automobile company, plan on a staff of 60 male handlers/packers62.

This measure was not specific to the USSR, since at the same time, in the Free French air force, “following a careful calculation realized by the Army staff services, it had been estimated that four women were needed to replace three men”63. The Soviet particularity lies in the fact that women had access to combat missions. In those cases, we can see that the military institution tried to reserve specialties for women requiring precision and patience, rather than intense physical effort. Sniper training in particular seems to answer to these qualities, and when, in December 1942 the Ministry of Defense launched a training plan for 60,000 women, it estimated that close to 20,000 of those women would serve in artillery and that more than twice as many would be trained as snipers. Moreover, a school devoted especially to women snipers was created near Moscow in 1943.

These measures take into account the physical effort needed during combat to carry munitions and load heavy weapons, while the matter of the strength demanded of cooks and laundresses (who carry heavy pails of water, handle cauldrons and wet sheets) is never brought up. However, the figures cited by the historian John Erickson give an idea of how harassing that work was:

Over a period of two years, the largely feminine staff of doctors, nurses and orderlies in evacuation hospital N° 2009 on the Western Front treated 515,678 casualties, loaded or unloaded 1119 hospital trains, carried out 52,848 surgical operations, applied 88,747 plaster casts and made 131,000 X-rays. Laundresses washed 154,100 kilograms of uniforms and bed-sheets, seamstresses repaired 798,000 sheets and 256,000 uniforms; cobblers mended 10,476 pairs of boots64.

The question of the physically exhausting tasks required of Soviet nurses and assistant nurses, responsible for dragging wounded soldiers to medical points and making sure they were safe. One of them spoke thus about her experience in Stalingrad:

I evacuated a minimum of 17-18 men per day. If there was too much shooting all around, you had to stretch the wounded man out on his cape or coat, crawl, drag him and drag yourself, or else get on your knees and drag him. It was very hard. Now that I’m back I tried to drag my younger sister like that and I didn’t manage to do it, not once65.

The burden weighing on nurses was all the greater as they also had to defend the wounded, arms in hand if necessary. In any case, that was the model proposed to them, that of Zina Piskunova, whose heroism was praised by the Soviet Red Cross in 1943:

Close to a village, a soldier was wounded by shrapnel from a mine. Zina crawled towards him and evacuated the wounded man by dragging him. But three fascist soldiers were hiding there. Without hesitating, the courageous young woman pulled out her gun and fired several shots. Two fascists fell, the third shot back. A fascist bullet his Zina in the shoulder. Backing up, she leaned on the wall of the building and shot her last bullets. The enemy fell down dead. Then Zina carefully bandaged the wounded soldier and, having gently installed him in the straw, again ran off into the fray to aid the wounded66.

Despite its propaganda aspect, this example reminds us to what point the distinction between combatant and non-combatant is far from being clear on the battlefield: a nurse can have to shoot, a soldier in arms becomes a nurse when in an emergency he gives first aid to his wounded companion. If we consider as combatants those who are “under fire”, what about nurses, male and female? Cynthia Enloe asks. She emphasizes that the same difficulty arises if we define as a combatant someone who holds a weapon and uses it: with the increasing sophistication of arms, is a person who launches a weapon kilometers away from the battlefield still a combatant67? Without providing definitive answers to these questions, the examples drawn from the practices of Soviet women combatants show to what extent the situation on the battlefield can demand combinations of different actions. This was emphasized by Vera Artamonova, trained at the Moscow Central School for Women Snipers, in her war memories of the front in Kaliningrad, 1944:

We weren’t always snipers. Sometimes we transported munitions, sometimes we went on reconnaissance, we played the role of nurses aides, or went into the trenches to shoot from the shooting posts. […] For example, during the advance on Nevel, crossing the Lovat river, we came up against fierce enemy resistance. I heard someone call out to me: ‘Nurse come bandage a wound!’ What should I do? Explain that I’m a sniper, not a nurse? That made no sense. I crawled over to him, then I ran, bent in two. I saw a wounded man stretched out next to the machine gun, and his teammate pulling him and ‘showering’, as we used to say. I bandaged the gunner and dragged him to the river, where the medical point was. I came back, and the one who was doing the ‘showering’, yelled out to me, ‘there’s no more bullets!’ I didn’t know where to find bullets, but the gunner didn’t care, he just got nervous and started swearing68.

This testimony indicates that several elements come into play in defining the function and role of the ‘female combatant’ during combat: the status of sniper (machine-gunner but also infantry soldier like the others), the immediate needs in combat situation (find reloads for the machine gun), the need to know how to give first aid. To these questions, which arise for all soldiers whatever their gender, are added, obviously, representations of women at the front, which explain that the young woman was considered a priori by soldiers to be a nurse.

Thus the experience of women indicates that the idea of a strictly respected division of tasks on the battlefield – which also underlies the distinction between combatant and non-combatant – is pretty much an illusion. Quentin Deluermoz comes to the same conclusion in his study of the Communardes, the women supporters of the Commune, who were members of the Bataillon des fédérés of the 12th arrondissement in 1871. For him, although “the overwhelming majority consisted of (women) ambulance drivers, canteen-workers or vivandières”, this sharing of roles was blurred on the terrain, women accompanying their husbands, carrying guns and munitions and able to “shoot in the storm of events”69.

Women Snipers of the Red Army during the Second World War.

Emphasizing the fluidity of statuses brings to light the fact that “waging war” involves a number of activities and functions, some of them not perceived as military, but nonetheless indispensable. When the head of the Komsomol, during a meeting of Soviet women partisans, said that “all support work deserves respect, and cooking a good meal is not to be looked down on either”70, one shouldn’t necessarily take that for a humorous remark or a form of condescendence. It was in fact one of the contributions of the history of women in resistance movements to have stressed “the contribution, together with the women of networks and movements, of numerous ‘ordinary’ women who provided essential aid in the form of hiding, housing, feeding and supplying”71. These functions – as important in the Soviet case as in the French case evoked by Françoise Thébaud – are however practically never mentioned. This silence can be linked more generally to the post-war invisibility of women combatants.

A painful post-war

One of the main questions posed by scholars working on war and gender is “knowing whether wars have only been parentheses, without any big changes in the supposed distribution of male-female tasks, or if conflicts have been the occasion for a transformation or attenuation of the sexual division of labor”72. The experience of European countries and North America during the two wars does not enable us to draw a simple conclusion73. On one hand, wars were the opportunity for women to participate in new domains, new experiences; on the other, in most cases “the return to order […] meant return to the order of the sexes”74.

Women were sent back to the private and family sphere, all the more so as demographic losses prompted worried governments to put in place more or less coercive pro-birth policies, and it was necessary to reintegrate demobilized men into the economy. For example, “at the end of the Second World War, only three of the 3,000 women employed at the Canadian Car and Foundry plant kept their jobs”75. The situation was slightly different in the USSR, where the rate of active women was already high before the Second World War: in 1940, women represented 39% of the Soviet work force. Nonetheless, there too we note an increase during the war followed by a significant decrease (56% of the work force in 1945, 47% in 1950)76.

Research on the situation of women after the Second World War or in the Latin-American or African guerillas77 show comparable situations: women not being taken into account in disarmament and demobilization programs, the difficulties of women soldiers to find a place in economic and family spheres, the effacement of their role in memorial policies (from names of streets to medals). A parallel can also be drawn with the post-war situation of Soviet women combatants, who had difficulty reintegrating and expressing their experience in a context where their participation in the conflict was either silenced, or rewritten solely from the angle of sacrifice.

Soviet policy at the end of the Second World War illustrates the thinking of Luc Capdevila. Whereas “in times of emergency, in situations of anomie, we repeatedly observe the presence of women combatants, and even of women’s combat units,” what is equally constant is “their disarmament during phases of ‘normalization’, corresponding to a political will to ‘return to order’”78.

In the USSR, women serving in the army were demobilized as of autumn 1945, shortly after the victory over Japan, and all were demobilized simultaneously, as women. The demobilization decree provided for the demobilization of “all women soldiers and sergeants,” whereas men were demobilized according to their age class, their specialties (agricultural and technical, teachers, students) or number of wounds79. Indeed the decree provides that “women specialists having expressed the desire to remain in the Red Army as soldiers” can pursue their careers, but in reality that was not the case, according to historian Reina Pennington. Very few women could continue to serve in military aviation, and if before the war they were discouraged from studying in military academies, after the war, their access was quite simply barred80.

Women were always necessary on the “work front”. However, the concern was evident to accelerate demographic growth, as can be seen in the maintenance of the prohibition of abortion (which was authorized only in 1955) and the adoption in 1944 of a law on the family. This law allowed the State to support more easily children born out of wedlock whose fathers did not pay, but also reinforced official marriage to the detriment of “civil marriage” (cohabitation, which until then had the same legal value)81. This policy affected in particular women who had served in the Red Army and had relations and/or children during the war with their masculine colleagues. The moral aspect of marriage reinforcement was in any case in line with public opinion hostile to women returning from the front, considered “women of disrepute”.

This situation is not characteristic of the USSR alone, since in France, Great Britain and the United States, rumors of the so-called easy virtue of women soldiers, treated like “women at the service of soldiers” were equally pervasive after the war. But the extreme difficulty of the four years of war in the USSR may also have exacerbated the hostility of the women who remained behind, “exhausted by work, under-nourishment, worries, fears every minute of the day, […] aged before their time, when told, not without embellishment, of the carefree lives of the young and hardy women at the front with no knowledge of rationing cards, queues and death notices, nor the unbearable solitude of women”82. Negative rumors were thus so widespread that an internal military report of October 1945 emphasized that:

…morale is bad among young demobilized women. […] We have come to a point […] where demobilized girls declare ‘we will not wear our medals when we go home […]. They say so many dirty things about us that they will all think our medals aren’t deserved’83.

“We didn’t tell anyone we’d been at the front […] At first, we didn’t even wear our decorations…” recalls, decades later, one of the women fighters whose memories are recorded in the book by Svetlana Alexevitch, Nobel prize-winner in literature. The pain of return is evident in the stories of these women, greeted by the hostility of those left behind: “They yelled at us, ‘We know perfectly well what you were doing out there! You were sleeping with our husbands. Soldiers’ whores! Sluts in uniform!’” Faced with such animosity, women resorted to silencing their experience: “the first year, when I got back from the war, I talked and talked. No one listened to me. Understood me. So I kept quiet…”84.

Thus for a large part, the discourse of women combatants became something not to be listened to, all the more so as the memory of the war itself was brought up very little during the years 1940-1950, when it was more a matter of the future and the building of communism. It was only in the early 1960s that Brezhnev, with the celebration of Twenty Years of Victory, attempted to make the Great Patriotic War a factor in the legitimation of the regime and of the unity of the Soviet people85. Although women’s participation in the war was then recognized, the memory of women combatants didn’t really have its place in a new mechanism that put female sacrifice first and foremost and was symbolized by the mutilated body of the partisan Zoya Kosmodemianskaya86.

Monument to the Glory of the Stalingrad Battle at Mamaev Kurgan, near Volgograd (1959-1967).

The monument of the battle of Stalingrad, erected between 1959 and 1967, clearly shows which feminine roles were given importance. Documents 4 (3 photos). The immense statue of the Motherland armed with a sword is surrounded only by masculine, martial figures. Only two statues of women answer the call of the Motherland: “the mother in mourning”, leaning, like a Pieta, over the body of a dead soldier, and a young nurse struggling beneath the weight of a wounded soldier. This rewriting of the place of women in the war, which would become the dominant discourse to the present day, is also noticeable in a speech by the president of the Union of Soviet Veterans in 1966. Before a meeting of women veterans, part of whom fought arms in hand, USSR marshal Timoshenko praised their heroism but denied its very real aspect of combat, referring only to their role as mothers:

Dear women comrades! It is you who give life, and no one more than you cherishes peace, tranquility and life on earth! […] As a veteran of the Soviet Armed Forces, I would like to say thank you to the women, to the mothers who raised strong and courageous sons, brave combatants, defenders of the Homeland87.

A comparison between experiences in the Red Army during World War II with those of Western countries and twentieth century resistance movements makes it possible to draw a certain number of conclusions regarding the question of women and war. First of all, the mobilization, integration, and demobilization of women raise similar issues and entail comparable modes of management. The recruitment of women in the army most often aims at the replacement of men in non-combatant functions (provisions, health), thus leaving men available for combat. Even in the case of a massive presence of women in the army, “combatant” functions remain the prerogative of men, women being accepted only exceptionally88. Moreover, women’s access to combat is neither a sign nor a guarantee that their overall situation will change, that their rights will be better respected after the war: in France, for example, women served in the army long before they obtained the right to vote. Almost everywhere, the upheavals linked to war cause tension later on over the sharing of traditional roles, all the more so when women are sent back to their family and maternal functions and their war experience obliterated.

In addition, focusing on women’s experience allows us to shed new light on the functioning of armies and the manner of waging war. The integration of women obliges the military institution to make adjustments that reveal to what extent what is perceived as “neutral” (sanitary conditions, uniforms, language) is in fact masculine. The discussion on criteria that would or would not allow a woman to have access to the status of combatant shows that in reality there is a multiplicity of tasks “under fire” and that the division between combatant and non-combatant is a fragile one.

Some of the points developed here deserve further exploration, always in a comparative sense, so as to fine-tune conclusions, particularly in the case of social origins and differences in incomes and education, which play an essential role in recruitment, but also in the experiences of women at the front. A higher level of education could (and still can) guarantee access to more prestigious functions or arms (artillery), but also to higher hierarchical positions – which, as we have seen, will in turn play a role in defense against sexual harassment. On the contrary, in the Red Army, as in other armies, women from more modest backgrounds were perhaps better prepared for the harsh conditions of the front. Social differences also determined how these women later describe their war, as they often deprive us of access to the memories of the less educated. In the Soviet case, for example, there is no memory of the tens of thousands canteen-servers or women working in the “bath and laundry units” – whereas the snipers, and they were only a few thousand, left numerous written narratives.

The other question I feel needs to be further explored is that of the links between military engagement and women’s rights. One is tempted to see on the part of these women who join the army a will to call gender relations into question, and although their presence in the army challenges these relations, this does not necessarily mean they meant to do so. Women combatants may also perceive their engagement as a necessary evil, at a specific moment when men can no longer ensure their traditional role of defender. It was just such a failing on the part of men that motivated the creation of women’s battalions in the Tsarist army in 191789, and that recently again motivated some of the Ukrainian women enlisting in the war in the East of their country, in 2014-1590. As Laurent Gayer writes, “one should be careful, here, not to project feminist conceptions of women’s liberation over these […] women’s experiences...”91.

The tendency to read their experience from the point of view of a defense of rights nonetheless exists. Indeed, even if feminists have competing views on the militarizing of women, the insertion of women in the army is always a struggle against sexist prejudice, which makes every victory against those prejudices seem like a victory for women’s causes92. Research on women combatants often implies that access to combat is the ultimate objective of women’s participation in war, and if they do not “access”, their tasks comprise a deprecatory lexicon: “restricted” to support functions, “relegated” to traditional tasks. Likewise, women’s return to the private sphere is quasi-unanimously analyzed as a “step backward”, whereas it can correspond, on the contrary, not only to personal aspirations, but also to a strategy of social ascension or to a desire to escape the difficulties of the working world93.

Thus, when saying in the introduction à propos of Anka the Machine-Gunner in the film, Chapaev that women weren’t seen as real soldiers, we implied that this non-recognition was problematic – and in fact, it may very well have been so for some women, who retained from their experience that “they had no confidence in us” and that “we had to fight to be considered correctly as women soldiers”94. For others, however, being a woman allowed them to play with the strict and burdensome rules of the military institution, and it offered a space of negotiated freedom: “we’d get to the point, when we had to see the commander, of going there head uncovered on purpose, so as not to have to salute”95. Therefore, although the status of women soldiers did not in the end mean male/female equality, the experience of these women can be viewed as an attempt to find a place for themselves by mobilizing personal resources and identity in a context which remained limited both by social inequalities, hierarchical organization, the constancy of traditional representations and above all, the weight and violence of war.

Notes

1

See the documents published by veterans of the 25th coastal division, which also bears the name Chapayev, in reference to this civil war hero: Trofim Kolomiets, Na bastionakh – chapaevtsy. Vospominaniia o legendarnoi 25 Chapaevskoi divizii, zashchishchavshei Sevastopol’ v 1941-1942 gg., Simferopol’, Krym, 1970; Vassili Sakharov (dir), U chernomorskikh tverdyn’ : Otdel’naia Primorskaia armiia v oborone Odessy i Sevastopolia, Moscou, Voenizdat, 1967; Iakov Vas’kovskii, Iuri Novikov, My – chapaevtsy. Dokumental’naia povest’ o 25-oi Chapaevskoi strelkovoi divizii, Moscou, DOSAAF, 1968.

2

This figure was given for the first time in V. Murmantseva, Sovetskie zhenshchiny v Velikoi Otechestvennoi voine, Moscou, Mysl’, 1974 (online).

3

See on this subject: Melissa Stockdale, “‘My Death for the Motherland is Happiness’: Women, Patriotism and Soldiering in Russia’s Great War, 1914-1917”, American Historical Review, vol. 1, n° 109, 2004, p. 78-116; Laurie Stoff, They Fought for the Motherland. Russia’s Women Soldiers in World War I and the Revolution, Lawrence (KS), University Press of Kansas, 2006, as well as the memoirs of Maria Bochkareva,Yashka, My Life as Peasant, Exile and Soldier, As told to Isaac Don Levine, New York, Frederick A. Stokes, 1919 available online.

4

On the training of Soviet women in the 1930s see: Anna Krylova, Soviet Women in Combat. A History of Violence on the Eastern Front, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2010; Olga Nikonova, “Soviet Amazons: Women Patriots During Prewar Stalinism”, Minerva. Journal of Women and War, vol. 2, n° 1, 2008, p. 84-99 and, by the same author, Vospitanie patriotov: OSOAVIAKHIM i voennaia podgotovka naseleniia v ural’skoi provintsii: 1927-1941, Moscou, Novyj khronograf, 2010.

5

Published in 1934, the short story “In the Town of Berdichev” was made into a film in 1967 by Askoldov entitled Commissar; Askoldov integrates the theme of the genocide of the Jews and the film was authorized in the USSR only at the end of the 1980s. See: Vassili Grossman, “In the Town of Berdichev”: The Road, short fiction and essays by Vassily Grossman (trans. by Robert & Elizabeth Chandler), New York Review of Books, 2010.

6

Jason Morton, “Fighting for a Role: The Lives of Anka-Pulemetchitsa”, BPS Working Papers Series, 2015 (online).

7

For this approach, see the pioneering work of Françoise Thébaud, La Femme au temps de la Guerre de 14 (Paris, Stock-Laurence Pernoud, 1986) as well as: Joshua S. Goldstein, War and Gender. How Gender Shapes the War System and Vice Versa, Cambridge, Cambridge UP, 2001; Luc Capdevila, François Rouquet, Fabrice Virgili, Danièle Voldman, Sexe, genre et guerres (France, 1914-1945), Paris, Payot, 2010; Sophie Milquet, Madeleine Frédéric (dir.), Femmes en guerres, Bruxelles, Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles, 2011; Philippe Nivet, Marion Trevisi, Les Femmes et la guerre de l’Antiquité à nos jours, Paris, Economica, 2010.

8

In the case of the USSR, there are interviews made during the war by historians of the Mints Commission (Academy of Science History Commission), conserved in the Institute of Russian History of the Academy of Sciences (IRI RAN). Numerous women’s memoirs were published in the 1960s, and new stimulus was given in the years 1990-2000, a great number of these testimonies being available online.

9

The majority of Orders of the Ministry of Defense and of the State Committee for Defense has been published in collections or is available online. Also used in this article are the archives of the Komsomol, the youth organization very active during the war, and those of the Party in Moscow (RGASPI – Rossiiskii Gosudarstvennyi Arkhiv Politicheskoi Istorii) and in Kiev (TsDAGO – Tsentralyi Derzhavnyi Arkhiv Gromodianskikh Orhanizatsii). Some of the documents cited here are conserved in the GARF (Gosudarstvennyi Arkhiv Rossiiskoi Federatsii) in Moscow.

10

Marielle Debos, “Conflits armés”, in Catherine Achin, Laure Bereni (dir), Dictionnaire genre & science politique, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 2013, p. 103-114.

11

Lætitia Bucaille, “Femmes à la guerre. Égalité, sexe et violence”, Critique internationale, n° 60, 2013, p. 10.

12

Boris Vasiliev wrote the scenario of a 1972 film by Stanislav Rostotski, and published it as a novel in 1975.

13

Luc Capdevila, François Rouquet, Fabrice Virgili, Danièle Voldman, Sexe, genre et guerres (France, 1914-1945), Paris, Payot, 2010.

14

Cited by Anna Krylova, Soviet Women in Combat. A History of Violence on the Eastern Front, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2010, p. 101.

15

Luc Capdevila, “La mobilisation des femmes dans la France combattante (1940-1945)”, Clio. Histoire, femmes et sociétés, n° 12, 2000.

17

All these decrees are available online.

18

Project of the GoKo decree on the training of 50 infantry brigades: “o formirovanii 50ti otdelnykh zhenskikh strelkovykh brigad”, RGASPI, fond М1, op. 47, delo 103, list 1-3.

19

Rough draft of the letter of the president of the Komsomol, Mikhailov, dated 10 February 1943, to the Chief of Staff in charge of recruitment, General T. Schadenko, RGASPI, fond М1, op. 47 delo 103, list 51.

20

Report of the brigade doctor, Divakov, associate president of the executive committee of the Union of the Soviet Societies of the Red Cross and Red Crescent (SOKK i KP) at the Komsomol, February 1943. RGASPI, fond M1, op. 47, delo 106, list 41-46.

21

Nancy Goldman, Richard Stites, “Great Britain and the World Wars”, in N. Goldman (dir), Female Soldiers. Combatants or Non-Combatants? Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, Westport (CT), Greenwood Press, 1982, p. 30.

22

George H. Quester “American dilemmas and options. The Problem”, in N. Goldman (dir), Female Soldiers. Combatants or Non-Combatants? Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, Westport (CT), Greenwood Press, 1982, p. 221.

23

Ultra Secret Report of the head of the Department Female Workers and Farmers of the Central Committee of the VKP(b) to all those in charge in the Republics, 2 March 1929: TsDAGO, fond 1, Op. 21, delo 34, list 1-2.

24

Komsomol CC order on the mobilization of young women in the special female infantry brigades, “Postanovlenia TsK VLKSM o mobilizatsii zhenskoi molodezhi v otdenlnye zhenskie strelkovye brigady”, 3 February 1943, RGASPI, fond М1, op. 47, delo 103, list 11.

25

Journal Officiel n° 11 of 13 February 1944 quoted by Luc Capdevila, “La mobilisation des femmes dans la France combattante (1940-1945)”, Clio. Histoire, femmes et sociétés, n° 12, 2000 (online).

26

Letter of General Smorodinov to USSR Marshal Voroshilov, copy to the president of the Komsomol Mikhailov, 17 March 1944: RGASPI, fond M1, op. 47, delo 153, list 1.

27

Catherine Merridale, “Masculinity at war: Did gender matter in the Soviet Army?”, Journal of War and Culture Studies, vol. 5, n° 3, 2013, p. 310.

28

Report of E. Shchadenko to Stalin on the state of reserves and recruits, 11-13 March 1942, quoted in: Sergei Kudriashov, Voina 1941-1945, Vestnik Arkhiv Prezidenta RF, Moscow, 2001, p. 124.

29

Cynthia Enloe, Does Khaki Become You? The Militarization of Women’s Life, Boston, South End Press, 1983, p. 123.

30

Euridice Charon Cardona, Roger D. Markwick, “‘Our brigade will not be sent to the front’: Soviet Women under Arms in the Great Fatherland War, 1941-45”, The Russian Review, vol. 68, n° 2, 2009, p. 240-262.

31

Boris Lavrenev, SorokPervyi, 1924 (online).

32

The “a” marks the feminization of the family name in Russian.

33

RGASPI, fond M7, op. 2, delo 1347, list 5.

34

RGASPI, fond M7, op. 2, delo 1347, list 8-9.

35

RGASPI, fond M7, op. 2, delo 1347, list 15.

36

Note that in French, for example, the term “soldate” is considered “familiar” by both the Larousse and the Robert dictionaries, which prefer the term “woman-soldier”.

37

Testimony of Lidia Alekseevna Bel’skaia (Tochilkina), published in October 2014.

38

Anna Krylova, Soviet Women in Combat. A History of Violence on the Eastern Front, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2010, p. 167.

39

Testimony of Irina Vladimirovna Iavorskaia in: Artem Drabkin, Bair Irincheev, “A zory zdes’ gromkie” : zhensoke litso voiny, Moscow: Eksmo, 2012, p. 102-103.

40

Testimony of Iudif’ Vladimirovna Golubkova, pubished in September 2006.

41

Testimony of Aleksandra Sergeevna Skiripochnkina: IRI RAN, fond 2, op. 7, delo 2a, list 6ob-7. I thank Brandon Schechter for this reference.

42

The issue of sanitary pads seems to be a key question in a number of other contexts. See for example: Jules Falquet, “Division sexuelle du travail révolutionnaire réflexions à partir de l’expérience salvadorienne (1970-1994)”, Cahiers des Amériques latines, n° 40, 2001, p. 109-128. (online)

43

Also in the United States, with the opening of all combat posts to women starting in 2016, the Pentagon had to design new protections specifically adapted to the morphology of women. See: Joseph Jaafari, “The Pentagon Is Finally Designing Combat Gear for Women”, Vice.com, 7 March 2016 (online).

46

Oleg Budnitskii, “Muzhchiny i zhenshchiny v Krasnoi Armii (1941-1945)”, Cahiers du monde russe, vol. 52, n° 2, 2011, p. 405-422.

47

Victoria Lanzona, Amazons of the Huk Rebellion. Gender, Sex, and Revolution in the Philippines, Madison, University of Wisconsin Press, 2009, p. 13.

48

Nancy Goldman, Richard Stites, “Great Britain and the World Wars”, in N. Goldman (dir), Female Soldiers. Combatants or Non-Combatants? Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, Westport (CT), Greenwood Press, 1982, p. 27.

49

Brandon M. Schechter, “‘Girls’ and ‘Women’. Love, Sex, Duty and Sexual Harassment in the Ranks of the Red Army 1941-1945” The Journal of Power Institutions in Post-Soviet Societies, n° 17, 2016 (online).

50

Research on rapes committed by the Red Army in Germany of course comes to mind, in particular the founding work by Norman Naimark (The Russians In Germany. The History Of The Soviet Zone Of Occupation, 1945-1949, Harvard, 1995), like that of Jeffrey Burds, “Sexual Violence in Europe in World War II, 1939-1945” (Politics Society, vol. 37 n° 1, 2009, p. 35-73). More generally, authors having recently published on Soviet women combatants (Budnitskii, Krylova, Schechter, Markwick and Cardonna) systematically raise the problem of harassment. The latter two authors worked with Artëm Drabkin, one of the creators of the site Iremember.ru and author of several compilations of memories that are best-sellers in Russia: the study of the questions posed on the site Iremember.ru shows that the women he interviewed were questioned on the subject of sexual harassment.

51

See for example Iulia Zhukova, Devushka so snaiperskoi vintovkoi. Vospominaniia vypusknitsy Tsentral’noi zhenskoi shkoly snaiperskoi podgotovki. 1944 1945 gg, Moscow, Tsentrpoligraf, 2006.

52

Brandon M. Schechter, “‘Girls’ and ‘Women’. Love, Sex, Duty and Sexual Harassment in the Ranks of the Red Army 1941-1945”, The Journal of Power Institutions in Post-Soviet Societies, n° 17, 2016 (online); Marta Havryshko, “Illegitimate sexual practices in the OUN underground and UPA in Western Ukraine in the 1940s and 1950s”, The Journal of Power Institutions in Post-Soviet Societies, n° 17, 2016 (online).

53

Testimony of Polina Georgievna Galanina: IRI RAN, fond 2, op. 7, delo 2a, list 2-2ob. I thank Brandon Schechter for this reference.

54

Letter of Staff Sergeant Nata Netiazhuk to the president of the Komsomol CC Mikhailov: RGASPI, fond M1, op. 47, delo 154, list 7.

55

John Erickson, “Soviet women at War”, in J. Garrard, C. Garrard (dir.), World War II and the Soviet People, New-York, St Martin’s Press, 2002, p. 51.

56

“Materialy soveshchaniia devushek-partizanok, sostoiavshego v TsK VLKSM 19-19 ianvaria 1944 goda”, RGASPI, fond M1, op. 53, delo 14, list 10.

57

“Materialy soveshchaniia devushek-partizanok, sostoiavshego v TsK VLKSM 19-19 ianvaria 1944 goda”, RGASPI, fond M1, op. 53, delo 14, list 9-10.

58

John Erickson, “Soviet women at War”, in J. Garrard, C. Garrard (dir.), World War II and the Soviet People, New-York, St Martin’s Press, 2002, p. 51.

59

En 1999, Maria Sirdar lost her case before the European Court of Justice against the British Royal Marines, who refused her a job as cook. In that case, the Court “accepted the idea that the fact of belonging of a member of a group to a given sex could offend the sensibilities of their colleagues of the other sex, or have a negative impact on it: in accordance with that reasoning, the presence of a woman in the Royal Marines could potentially weaken the cohesion of the unit”. See Irène Eulriet, “Le recrutement des femmes dans les forces armées des États membres de l’Union Européenne: entre contrainte et mutation”, in C. Weber (dir.), Les Femmes militaires, Rennes, PUR, 2015, p. 44.

60

Martin van Creveld, Wargames. From Gladiator to Gygabites, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2013, p. 278.

61

Intervention by partisan Makarova, Karelian front, (“Materialy soveshchaniia devushek-partizanok, sostoiavshego v TsK VLKSM 19-19 ianvaria 1944 goda”, RGASPI, fond M1, op. 53, delo 14, list 32).

62

“Spravki otdela, perepiski, informatsia o formirovanii zhenskoi dobrovolcheskoi strelkovoi brigady”, november the 27th, 1942, RGASPI, fond M1, op. 47, delo 50.

63

Luc Capdevila, “La mobilisation des femmes dans la France combattante (1940-1945)”, Clio. Histoire, femmes et sociétés, n° 12, 2000 (online).

64

John Erickson, “Soviet women at War”, in J. Garrard, C. Garrard (dir.), World War II and the Soviet People, New-York, St Martin’s Press, 2002, p. 51.

65

Testimony of Asia Ivanovna Kakedzhan : IRI RAN, fond 2, op. 7, delo 5, list 5. Reference communicated to me by Brandon Schechter.

66

Report of brigade doctor Divakov, assistant president of the executive committee of Union of the Soviet Societies of the Red Cross and Red Crescent (SOKK i KP) to the Komsomol, February 1943. RGASPI, fond M1, op. 47, delo 106, list 40a-40a ob.

67

Cynthia Enloe, Does Khaki Become You? The Militarization of Women’s Life, Boston, South End Press, 1983, p. 150 sqq.

68

Memories of Vera Artamonova (no date) in Elizaveta Nikiforova (dir.), Rozhdennaia voinoi, Moscow, Molodaia Gvardia, 1985, p. 66.

69

Quentin Deluermoz, “Des communardes sur les barricades”, in C. Cardi, G. Pruvost (dir.), Penser la violence des femmes, Paris, La Découverte, 2012, p. 114.

70

Intervention of comrade Sysoevak “Materialy soveshchaniia devushek-partizanok, sostoiavshego v TsK VLKSM 19-19 ianvaria 1944 goda”, RGASPI, fond M1, op. 53, delo 14, list 11.

71

Françoise Thébaud, “Résistances et Libérations”, Clio. Histoire, Femmes et Sociétés, n° 1, 1995 (online).

72

Luc Capdevila, François Rouquet, Fabrice Virgili, Danièle Voldman, Sexe, genre et guerres (France, 1914-1945), Paris, Payot, 2010, p. 224.

73

Françoise Thébaud, “Penser les guerres du XXe siècle à partir des femmes et du genre. Quarante ans d’historiographie”, Clio. Femmes, Genre, Histoire, n° 39, 2014 (online).

74

Coline Cardi, Geneviève Pruvost (dir.), Penser la violence des femmes, Paris: La Découverte, 2012: 37.

75

“Grandes Guerres. Grandes Femmes”, presentation brochure of the exposition in the Canadian Museum of War in Ottawa, from 23 October 2015 to 3 April 2016.

76

Mie Nakachi, “A postwar sexual liberation? The gendered experience of the Soviet Union’s Great Patriotic War”, Cahiers du monde russe, vol. 52, n° 2, 2011: 424.

77

Camille Boutron, “Réintégrer la vie civile après le conflit : entre invisibilisation et résistance. L’expérience des ronderas au Pérou”, in N. Duclos (dir.), L’Adieu aux armes? Parcours d’anciens combattants, Paris: Karthala, 2010: 111-142; Jules Falquet, “Les Salvadoriennes et la guerre civile révolutionnaire”, Clio. Histoire, Femmes et Sociétés, n° 5, 1997 (online) ; Oksana Kis, “National Femininity Used and Contested: Women’s Participation in the Nationalist Underground in Western Ukraine during the 1940s-50s”, East/West. Journal of Ukrainian Studies, vol. 2, n° 2, 2015: 53-82 (online); Dyan Mazurana, Linda Eckeborn Cole, “Women, Girls and Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration”, in C. Cohn, Women and Wars, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2013: 194-214.

78

Luc Capdevila, “Identités de genre et événement guerrier. Des expériences féminines de combat”, in S. Milquet, M. Frédéric (dir.), Femmes en guerres, Bruxelles: Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles, 2011: 17.

80

Reina Pennington, “‘Do not speak of the services you rendered’: Women veterans of aviation in the Soviet Union”, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies, vol. 9, n° 1, 1996: 141.

81

Mie Nakachi, “A postwar sexual liberation? The gendered experience of the Soviet Union’s Great Patriotic War”, Cahiers du monde russe, vol. 52, n° 2, 2011: 433.

82

Lev Kopelev, Khranit’ vechno, t. I, Moscow: Terra, 2004: 91-92.

83

“Spravka o voprosakh, sviazannykh s demobilizatsiei iz Armii voennosluzhashchikh pervoi i vtoroi ocheredi, utverzhdena nachal’nikom politupravlenii Sovetskikh okkupatsionnykh voisk v Germanii” [“Report on issues linked to the first and second wave of demobilization, validated by the head of the political division of Soviet Occupation Forces in Germany”],11 October 1945, RGASPI, fond M1, op. 47, delo 193, list 49.

84

Svetlana Alexiyevich, War's Unwomanly Face, Moscow, Progress Publisher, 1988. Quoted from French version, La Guerre n’a pas un visage de femmes (trad. G. Ackerman, P. Lequesne), Paris: J’ai Lu, 2005: 56, 320.

85

Lev Gudkov “Pamiat o voine i massovaia identichnost Rossiian”, Neprikosnovennyi Zapas, vol. 40-41, n° 2-3, 2005 (online); Mikhail Gabovich (dir.), Pamiat’ o voine 60 let spustia : Rossiia, Germaniia, Evropa, Moscow: NLO, 2005.

86

Anna Krylova, Soviet Women in Combat. A History of Violence on the Eastern Front, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010: 292 sqq. Adrienne M. Harris, “Memorializations of a martyr and her mutilated bodies: public monuments to Soviet war hero Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya, 1942 to the present”, Journal of War and Culture Studies, vol. 5, n° 1, 2012: 73-92.

87

“Stenogramma sobrania aktiva zhenschin veteranov voiny” (Sténogramme de la réunion des représentantes des femmes vétérans de la guerre), 15-16 mars 1966 : GARF, fond 9541, op. 1, delo 998, list 3-4.

88

In Israel, although women have done their military service for a long time, their access to combat functions was given after a 1995 Supreme Court decree obliging aviation to accept to train women pilots. It remains that “although women represent 3% of the staff qualified as combatants, they are absent from the real hard core: infantry, tanks, reconnaissance units”. Orna Sasson-Levy, Edna Lomsky-Feder, “Genre et violence dans les paroles de soldates: le cas d’Israël” (trad. R. Bouyssou), Critique internationale, n° 60, 2013: 77.

89

Maria Botchkareva, Yashka. Journal d’une femme combattante, Russie 1914–1917 (éd. S. Audoin-Rouzeau, N. Werth), Paris: Armand Colin, 2012.

90

Amandine Regamey, Brandon M. Schechter, “Introduction”, The Journal of Power Institutions in Post-Soviet Societies, n° 17, 2016, § 27 (online).

91

Laurent Gayer, “Liberation and containment: The Ambivalent Empowerment of Sikh Female fighters”, Pôle Sud, n° 36, 2012: 63.

92

Cynthia Enloe, Does Khaki Become You? The Militarization of Women’s Life, Boston: South End Press, 198: 100.

93

Laurent Gayer, “Liberation and containment: The Ambivalent Empowerment of Sikh Female fighters”, Pôle Sud, n° 36, 2012: 49-65.

94

Intervention of comrade Melnik, female aviator in a feminine regiment, before the president of the USSR, Kalinine, 26 July 1945 (“Beseda tovarisha Kalinina s devushkami voinami, steogramma”), RGASPI, fond M1, op. 5, delo 245, list 6-7.

95

Testimony of comrade Andronova, delegate of young women soldiers of anti-aircraft defense of the Central Front before the president of the USSR, Kalinine, 26 July 1945 (“Beseda tovarisha Kalinina s devushkami voinami, steogramma”), RGASPI, fond M1, op. 5, delo 245, list 2.

Bibliographie

Svetlana Alexievitch, War's Unwomanly Face, Moscow, Progress Publisher, 1988.

Stéphane Audoin-Rouzeau, “Armées et guerres: une brèche au cœur du modèle viril?”, in A. Corbin, J.-J. Courtine, G. Vigarello (dir.), Histoire de la virilité. XXe-XXIe siècles, t. III, Paris, Le Seuil, 2011, p. 201-223.

Maria Botchkareva, Yashka, My Life as Peasant, Exile and Soldier, as told to Isaac Don Levine, New York, Frederick A. Stokes, 1919. Available online.

Lætitia Bucaille, “Femmes à la guerre. Égalité, sexe et violence”, Critique internationale, n° 60, 2013, p. 9-19.

Oleg Budnitskii, “Muzhchiny i zhenshchiny v Krasnoi Armii (1941-1945)”, Cahiers du monde russe, vol. 52, n° 2, 2011, p. 405-422.

Jeffrey Burds, “Sexual Violence in Europe in World War II, 1939-1945”, Politics Society, vol. 37 n° 1, 2009, p. 35-73.

Luc Capdevila, “La mobilisation des femmes dans la France combattante (1940-1945)”, Clio. Histoire, Femmes et Sociétés, n° 12, 2000.

Luc Capdevila, “Identités de genre et événement guerrier. Des expériences féminines de combat”, in S. Milquet, M. Frédéric (dir.), Femmes en guerres, Bruxelles, Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles, 2011.

Luc Capdevila, François Rouquet, Fabrice Virgili, Danièle Voldman, Sexe, genre et guerres (France, 1914-1945), Paris, Payot, 2010.

Coline Cardi, Geneviève Pruvost (dir.), Penser la violence des femmes, Paris, La Découverte, 2012.

Euridice Charon Cardona, Roger D. Markwick, “Our brigade will not be sent to the front: Soviet Women under Arms in the Great Fatherland War, 1941-45”, The Russian Review, vol. 68, n° 2, 2009, p. 240-262.

Marielle Debos, “Conflits armés”, in C. Achin, L. Bereni (dir), Dictionnaire genre & science politique, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 2013, p. 103-114.

Quentin Deluermoz, “Des communardes sur les barricades”, in C. Cardi, G. Pruvost (dir.), Penser la violence des femmes, Paris, La Découverte, 2012.

Artem Drabkin, Bair Irincheev, “A zory zdes’ gromkie: zhensoke litso voiny”, Moscow, Eksmo, 2012.

Cynthia Enloe, Does Khaki Become You? The Militarization of Women’s Life, Boston, South End Press, 1983.

John Erickson, “Soviet Women at War”, in J. Garrard, C. Garrard (dir.), World War II and the Soviet People, New-York, St Martin’s Press, 2002.

Irène Eulriet, “Le recrutement des femmes dans les forces armées des États membres de l’Union Européenne: entre contrainte et mutation”, in C. Weber (dir.), Les Femmes militaires, Rennes, PUR, 2015, p. 41-55.

Jules Falquet, “Les Salvadoriennes et la guerre civile révolutionnaire”, Clio. Histoire, Femmes et Sociétés, n° 5, 1997.

Jules Falquet, “Division sexuelle du travail révolutionnaire réflexions à partir de l’expérience salvadorienne (1970-1994)”, Cahiers des Amériques latines, n° 40, 2001, p. 109-128.

Mikhail Gabovich (dir.), Pamiat’ o voine 60 let spustia: Rossiia, Germaniia, Evropa, Moscow, NLO, 2005.

Laurent Gayer, “Liberation and Containment: The Ambivalent Empowerment of Sikh Female fighters”, Pôle Sud, n° 36, 2012, p. 49-65.

Nancy Goldman, Richard Stites, “Great Britain and the World Wars”, in N. Goldman (dir), Female Soldiers. Combatants or Non-Combatants? Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, Westport (CT), Greenwood Press, 1982.

Vassily Grossman, “In the Town of Berdichev”. The Road, Short Fiction and Essays, New York, New York Review of Books, 2010.

Lev Gudkov, “Pamiat o voine i massovaia identichnost Rossiian”, Neprikosnovennyi Zapas, vol. 40-41, n° 2-3, 2005.

Adrienne M. Harris, “Memorializations of a Martyr and her Mutilated Bodies: Public Monuments to Soviet war hero Zoya Kosmodemyanskaya, 1942 to the Present”, Journal of War and Culture Studies, vol. 5, n° 1, 2012, p. 73-92.

Marta Havryshko, “Illegitimate sexual practices in the OUN underground and UPA in Western Ukraine in the 1940s and 1950s”, The Journal of Power Institutions in Post-Soviet Societies, n° 17, 2016.

Joseph Jaafari, “The Pentagon Is Finally Designing Combat Gear for Women”, Vice.com, 7 mars 2016.

Oksana Kis, “National Femininity Used and Contested : Women’s Participation in the Nationalist Underground in Western Ukraine during the 1940s-50s”, East/West. Journal of Ukrainian Studies, vol. 2, n° 2, 2015, p. 53-82.

Trofim Kolomiets, Na bastionakh – chapaevtsy. Vospominaniia o legendarnoi 25 Chapaevskoi divizii, zashchishchavshei Sevastopol’ v 1941-1942 gg., Simferopol’, Krym, 1970.

Lev Kopelev, Khranit’ vechno, t. I, Moscow, Terra, 2004.

Anna Krylova, Soviet Women in Combat. A History of Violence on the Eastern Front, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Sergei Kudriashov, Voina 1941-1945, Vestnik Arkhiv Prezidenta RF, Moscow, 2001.

Victoria Lanzona, Amazons of the Huk Rebellion. Gender, Sex, and Revolution in the Philippines, Madison, University of Wisconsin Press, 2009.

Boris Lavrenev, SorokPervyi, 1924.

Carol Mann, Femmes dans la guerre. 1914-1945, Paris, Pygmalion, 2010.

Dyan Mazurana, Linda Eckeborn Cole, “Women, Girls and Disarmament, Demobilization and Reintegration”, in C. Cohn, Women and Wars, Cambridge, Polity Press, 2013, p. 194-214.

Catherine Merridale, “Masculinity at war: Did gender matter in the Soviet Army?”, Journal of War and Culture Studies, vol. 5, n° 3, 2013, p. 307-320.

Sophie Milquet, Madeleine Frédéric (dir.), Femmes en guerres, Bruxelles, Éditions de l’Université de Bruxelles, 2011.

Jason Morton, “Fighting for a Role : The Lives of Anka-Pulemetchitsa”, BPS Working Papers Series, 2015.

Vera Semenovna Murmantseva, Sovetskie zhenshchiny v Velikoi Otechestvennoi voine, Moscow, Mysl’, 1974.

Norman Naimark, The Russians In Germany. The History Of The Soviet Zone Of Occupation, 1945-1949, Harvard, Harvard University Press, 1995.

Mie Nakachi, “A postwar sexual liberation? The gendered experience of the Soviet Union’s Great Patriotic War”, Cahiers du monde russe, vol. 52, n° 2, 2011, p. 423-440.

Elizaveta Nikiforova (dir.), Rozhdennaia voinoi, Moscow, Molodaia Gvardia, 1985.

Olga Nikonova, “Soviet Amazons: Women Patriots During Prewar Stalinism”, Minerva. Journal of Women and War, vol. 2, n° 1, 2008, p. 84-99.

Olga Nikonova, Vospitanie patriotov: OSOAVIAKHIM i voennaia podgotovka naseleniia v ural’skoi provintsii: 1927-1941, Moscow, Novyj khronograf, 2010.

Philippe Nivet, Marion Trevisi, Les Femmes et la guerre de l’Antiquité à nos jours, Paris, Economica, 2010.

Reina Pennington, “Do not Speak of the Services you Rendered: Women Veterans of Aviation in the Soviet Union”, The Journal of Slavic Military Studies, vol. 9, n° 1, 1996, p. 120-151.

George H. Quester, “American Dilemnas and Options. The Problem”, in N. Goldman (dir), Female Soldiers. Combatants or Non-Combatants? Historical and Contemporary Perspectives, Westport (CT), Greenwood Press, 1982.

Amandine Regamey, Brandon M. Schechter, “Introduction”, The Journal of Power Institutions in Post-Soviet Societies, n° 17, 2016, p. 27.

P. Sakharov (dir), U chernomorskikh tverdyn’: Otdel’naia Primorskaia armiia v oborone Odessy i Sevastopolia, Moscow, Voenizdat, 1967.

Orna Sasson-Levy, Edna Lomsky-Feder, “Genre et violence dans les paroles de soldates: le cas d’Israël”, Critique internationale, n° 60, 2013, p. 71-88.

Brandon M. Schechter, “Girls' and Women. Love, Sex, Duty and Sexual Harassment in the Ranks of the Red Army 1941-1945”, The Journal of Power Institutions in Post-Soviet Societies, n° 17, 2016.

Melissa Stockdale, “My Death for the Motherland is Happiness: Women, Patriotism and Soldiering in Russia’s Great War, 1914-1917”, American Historical Review, n° 109, 2004, p. 78-116.

Laurie Stoff, They Fought for the Motherland. Russia’s Women Soldiers in World War I and the Revolution, Lawrence (KS), University Press of Kansas, 2006.

Françoise Thébaud, La Femme au temps de la Guerre de 14, Paris, Stock-Laurence Pernoud, 1986.

Françoise Thébaud, “Résistances et Libérations”, Clio. Histoire, Femmes et Sociétés, n° 1, 1995.

Françoise Thébaud, “Penser les guerres du XXe siècle à partir des femmes et du genre. Quarante ans d’historiographie”, Clio. Femmes, Genre, Histoire, n° 39, 2014, p. 157-182.

Martin van Creveld, Wargames. From Gladiator to Gygabites, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2013.

Iakov Vas’kovskii, Iuri Novikov, My – chapaevtsy. Dokumental’naia povest’ o 25-oi Chapaevskoi strelkovoi divizii, Moscow, DOSAAF, 1968.

Iulia Zhukova, Devushka so snaiperskoi vintovkoi. Vospominaniia vypusknitsy Tsentral’noi zhenskoi shkoly snaiperskoi podgotovki. 1944 1945 gg, Moscou, Tsentrpoligraf, 2006.