Numerous works offer more or less extensive descriptions or classifications that distinguish political organizations on the basis of ideological principles which are tacitly considered immutable and shared by the members. In addition, two major traditions for analyzing political parties can be identified1. The first attempts to account for their creation and their leanings based on the links that each organization has with one or more social groups. Thus, Marxist analysis sees parties as representatives of the interests of classes or fractions of social classes2. More generally, Seymour M. Lipset and Stein Rokkan argue that parties are a component of the “sides” of territorial, national, religious, social and ideological divisions, resulting from the various national, industrial and international revolutions that have marked the Western history3. These theoretical orientations can be described as “heteronomising”, because they claim to account for partisan activity from “outside”, through the favored prism of the representation of more or less widely defined social interests. Given this, they tend to leave aside the “internal mechanisms” of the creation, organization, and functioning of political parties.

Karl Marx, 1875.

On the other hand, an "autonomizing" tradition puts specific partisan activities and interests at the heart of its analysis and explanations. For Edmond Burke, a party is a “group of men” who have agreed on “a certain principle”, or a vision, which has an affinity with the common-sense conception of a party as defined by its “ideology”. In contrast to such interpretations, Joseph Schumpeter contends that a party “is a group whose members propose to act together in the competitive struggle for political power”4. The Austrian economist agrees with Max Weber when the latter argues that “all partisan struggles are not only struggles for objective goals but also, and above all, rivalries to control the distribution of jobs”. These jobs are necessary for professional politicians, who live for and off politics, and also for their “supporters for their good and loyal services”5. From the point of view of this theoretical tradition, political activity is an enterprise – i.e. a continuous activity towards a finality of a specified kind6 – and all political enterprises are necessarily enterprises of interests7. For Weber, “this means that a relatively small number [my italics] of men are primarily interested in political life and wish to hold power, recruit freely-willing partisans, stand as candidates for election or put forward their protégés, raise necessary finance and hunt for votes”8. However, beyond their divergences, these two intellectual traditions share the fact that they do not include the issue of activism in their theoretical construction.

Max Weber, Le Savant et le politique, Paris, [Plon, 1959] La Découverte, 2003.

Activism as a non-analyzed phenomenon

In the “indigenous” political vocabulary, an “activist” is an active member of a movement, such as a party. He or she acts “at the base”, or at the grassroots level, as a subordinate, and “voluntary worker”, with no compensation. Nor does the activist hold any position of power in the State, or in the management of the organization. Activists have played and still play an important role in the activities of collective organizations. The way the two main theoretical traditions largely ignore their work is therefore obviously damaging, even though the role of activists has undoubtedly declined during the last decades.

The decline and persistence of activist practices

This regression is a consequence of the development of professional political activity. It is possible to live for and off politics as a “permanent staffer” paid by a party, holding a position in an organization controlled by a party, or being elected to representative institutions. These were the paths that have long been taken by persons participating “directly” in the competition for the conquest of positions of political power. More recently, there has been an increase in the number of persons who also live for and off politics, but acting on behalf of others: assistants, councilors and members of offices of MPs and elected leaders of local government. The number of such collaborators is increasing, due to the enhancement of teams formed around parliamentarians and locally elected representatives. A new way of accessing the field of professional politics has become institutionalized as a result of this transformation: students who are members of a trade union or a party are recruited to work in the entourage of an elected official. When they complete their studies, they enter the world of politics directly, without having had other professional experience, and some of them will pursue a political career on their own account. For several decades, a market for political advice has also developed. Firms with specialists in public relations, opinion polls, communication, and marketing have proliferated.

The invasion of political polls, 2017.

These developments have contributed to reducing the space of activists' accomplishments. The number of party members is decreasing. Collaborators, or specialists in communication companies, who are paid for their services, have now taken over some of the tasks that used to be done by activists. Handmade posters and leaflets have been replaced by more sophisticated material – formally speaking – produced by these companies. Neighborhood electoral meetings have become scarce and their scope has been reduced. They have been replaced by large gatherings. Once again, specialized firms stage these rallies spectacularly, in order to attract the attention of television channels. Though they have not disappeared, grassroots mobilizations via the distribution of leaflets, door-to-door canvassing, and the sale of partisan newspapers have lost their importance in relation to remote mobilizations conducted through the media, in particular television. Activism also seems to have lost its intensity: few activists today devote most of their free time to political activities, as was probably more often the case in the 1960s or 1970s. The engagement is perhaps more “distanced”, even if this is not always the case9.

However, while it has weakened, the contribution of activists to the functioning of political parties has not disappeared and must be included in a theory of political enterprises. Moreover, activism exists not just for political purposes. It also exists in unions and non-profit associations, and it is developing outside organizations in social movements. This justifies the search for general explanatory hypotheses. Their absence leaves the field open to spontaneous theories based on common sense, which have emerged especially in the development of organizations.

Spontaneous theories of activism

The activist universes are (still?) “officially” considered as being disinterested, albeit in a diffuse way. But this may vary according to organizations, individuals, and historical contexts. They have the reputation of defending legitimate causes, collective interests, or “ideals”, and so attract (among others) persons who value (more or less) non-market activities, dedication, voluntary work, generosity, self-sacrifice, solidarity, and the general interest. They contrast with, and derive many of their characteristics from their opposition to economic or power spheres, which accept and even legitimize the search for benefit, enrichment, notoriety, power, prestige, social ascension, and self-interest.

These activist universes are organized around the promotion of a collective cause. They censor (again unequally, but always minimally) the personal interests of activists, partly because any overly obvious manifestation of such personal interests could cast suspicion on the cause and its collective purpose. Voluntary organizations tacitly distinguish (when necessary) between acceptable behavior, demands, and justifications (e.g. satisfactions associated with a feeling of effectiveness in support of the cause), and others, which are not. They derive their characteristics from a harmony between leaning towards “disinterested behavior” (unequally constituted, but probably minimally so) of at least a share of their members, and a mode of functioning that rewards them10. The “sacralization” of the cause and the “sanctification” of the actions carried out in its favor are accompanied by the (more or less severe) stigmatization of the search for individual benefits when this quest is too overt and concentrated on individual gains.

Campaign together, for the same cause. World social forum of Dakar, on 2011.

Source : Médias citoyens.

Those who adhere to the cause share these beliefs. But they face indifference, skepticism, and even the hostility from persons who remain outside the organization, are leaving it, or have freed themselves from it. Collective advocacy organizations are therefore also based on beliefs. There are no collective actions, interests, and goods per se. The dispositions and representations of persons taking up the cause ensure that actions carried out in common, shared interests, and objectives assigned to the mobilization are indeed “collective”. The volunteer quality of activism is all the stronger because it does not give rise to monetary compensation. In a society in which “interests” are largely assumed to be pecuniary, the absence of financial compensation is easily perceived as evidence of disinterested behavior. This is especially so for people working at grassroots level (the base) without exercising power.

As an extension of such “indigenous” perceptions, current descriptions of activism attribute a decisive role to ideological, political, or “moral” motives in explaining membership, activism, or defection. Party membership and activism are thus described as disinterested practices, resulting from a personal awareness and a willingness to devote oneself, and even to sacrifice oneself, to a collective cause, such as a moral principle, or the interests of a country, a nation, a religion, a group, or a social class.

The weaknesses of spontaneous theories

Ces théories spontanées présentent divers points aveugles, faiblesses et apories. L'adhésion à la cause partisane y est présentée comme formée antérieurement à l'entrée et indépendamment de l'entrée dans l'organisation. Un tel postulat est en contradiction avec diverses observations, sur lesquelles on reviendra, qui suggèrent que, au moins dans certains cas, l'adhésion à la cause et la capacité à la défendre tendent à se développer au fur et à mesure de l'engagement à son service. Ce postulat revient également à poser que tous les adhérents d'un parti politique sont également intéressés par les dimensions politiques, idéologiques et programmatiques de ses activités et également en mesure de les maîtriser. De tels présupposés sont eux aussi contredits par diverses observations. Ils ne permettent pas non plus d'expliquer comment certains partis peuvent mobiliser des hommes et des femmes issus des catégories les plus à distance du politique.

“Porteurs de parole”, Young Greens.

Source : Jeunes-écologistes.org

Another paradox of the spontaneous theories of activism lies in the way they deny the existence of personal “interests” that seem self-evident to leaders. Weber, for example, details the reasons for political professionalization: “someone who lives for politics makes it, in the deepest sense of the term, the goal of his/her life, either because they enjoy the mere possession of power, or because such activity enables them to find an internal equilibrium and express their personal value by putting themselves at the service of a cause that gives meaning to their lives”11. Weber suggests that party functionaries mainly hope for “positions” in reward for their dedication. However, concerning activists, Weber only sees “the satisfaction that men experience in working with the devotion of a believer for the success of the cause of a personality, and not so much in the interests of the abstract mediocrities of a program”12.

Lastly, there are theoretical objections to the spontaneous theories of activist devotion. If activist commitment results from a state of awareness, what are its conditions? Why would such awareness be found in some people and not others? Why do some people join an organization when others do not? Following Mancur Olson's analyzes13, though without endorsing his materialistic, rationalist, objectivist, and intentionalist presuppositions, it may be asked whether persons who bear various “costs”, and sometimes take risks, in the service of a collective good, whose attainment, or even mere pursuit, benefits a wider group, are not in fact motivated by various “selective incentives”.

Observed rewards of activist activities

Direct observation, the written testimony left by some, and statements gathered during conversations or research interviews, all make it clear that activists do indeed derive various forms of satisfaction from their commitment. These sensitive aspects of their activity can be analyzed as “compensation” mechanisms, or rather as rewards for involvement in the activities of a collective movement.

For leaders, these “unofficial” incentives come from the occupation of positions of power in government or in their organization. They include sources of income, material advantages, the possibility of living from politics, of acting in accordance with one’s ideological and political convictions, and/or various symbolic gratifications, such as prestige, notoriety, honor, and power. For permanent staffers and other salaried employees, the commitment provides access to paid employment, which makes it easier to deal with the availability required for commitments to a cause. Hierarchical positions in an organization at various levels are not always paid, but provide de facto gratification by various advantages such as self-esteem, power (access to restricted information, a sense of importance, the satisfaction of action, the power over things or people), the fact of being notable (recognition, prestige, titles to intervene in various public forums), as well as by the esteem, the affection, and sometimes the admiration, of comrades in the cause.

The “Perchoir”, Assemblée nationale.

Even if the “simple activists” do not have access to such benefits of power, their commitment nevertheless gives them various satisfactions, which also contribute to supporting and even reinforcing their willingness to invest in collective action14. The feeling of acting for a just cause rather than suffering, the sentiment of transforming, or of being able to transform reality, sometimes of making history, provide or reinforce the reasons to engage in an organization. The time given to a cause, the efforts completed, the renunciations of the pleasures of “ordinary” life, the sacrifices made, the risks sometimes endured, may all help activists find peace of mind, serenity, plenitude, and various moral satisfactions. These even include a feeling of ethical superiority.

The activists also have opportunities to be informed and enter (more or less) into the great debates about the affairs of their country and the world. Some develop self-learning habits and acquire tools to understand their environment, and sometimes skills to accumulate information, to organize arguments, and to speak in public. Activists thus manage to compensate, at least partially, for their educational and cultural handicaps, to fight their feelings of ignorance, cultural indignity, political incompetence, or lack of self-esteem, and so alleviate the stigmatization they may suffer from15. Some activists enjoy their intellectual enrichment and recount their amazement at discovering the (legitimate) culture favored by activism. Organization members also take part in competitive internal games, sometimes for their own account, or in the pride of rubbing shoulders with “leading personalities”. Activist engagement can provide the opportunity of fulfilling gratifying social roles and contributing to self-assertion and self-esteem. Some activists find a way of overcoming family exclusions, work precariousness, unemployment, or marginalization16.

Training workshop, summer school of the French Communist Party, Angers, 2017.

Organize, inquire, to meet: some bonuses of the political activism in period of election campaign (Clamart citoyenne, 2014).

The activist experience and the relational capital it procures (deliberately or not) can also facilitate entry into the labor market or professional reorientation. Some activists find (without necessarily seeking them) clients, orders, or rewarding ways of practicing their profession by putting it to the service of an ideal17. For the most-involved activists, commitment is also an opportunity of sociability, integration, and friendship, sometimes a source of love life, conviviality and leisure. It may offer a touch of adventure in contrast to the routines of everyday life. For example, activism may procure a certain frisson when putting up posters at night, while being threatened by opposing groups, or – at another level – when volunteers have to carry out missions in countries facing civil war. For intellectuals, activism provides them with official positions to intervene in public debates, access to forums, publishing possibilities, and opportunities for debate with renowned peers, and gains in notoriety.

In all these cases, the chances of benefiting in areas outside collective action constitute internal benefit mechanisms. Multi-positioning in separate fields may make it possible to mobilize intellectual resources in spheres of activism and activists’ experiences in intellectual output. As a result, as long as they are caught by their commitments, activists often assign a value to these satisfactions, though in practice they may not always be fully aware of this, or even deny it. The value given to such satisfactions determines the rewards activists obtain (see below). The appropriation and the obstacles to the appropriation of these satisfactions, as well as their fluctuating value are therefore an important element in understanding and explaining (among other things) the investments and disinvestments of activists. Satisfactions of all types drawn from involvement favor orthodoxy, while reductions in gratifications contribute to defections and internal opposition. The internal order of an organization thus depends on the possibilities of rewarding members. Certain features of activism or the structuring of organizations (e.g. the multiplication of “responsibilities” at various levels) follow on from this imperative.

It is also necessary to account for the energy that leads women and men to give up certain things and take risks. These can sometimes be considerable. From an external point of view, but also (more or less) from the point of view of some participants, activist engagement is “expensive” in time, energy, availability, drudgery, sacrifice, and prejudice, whether these are actual or potential. This is especially so as the benefits generated by an engagement are likely to contend with other obligations, happiness, and rewards of family life, love life, school or working life, or indeed alternative investments. The fragility, and in some cases the weakness, of benefit-sharing processes linked to activism are in principle reflected in the volatility of commitment and membership turnover. These are structural components of collective organizations and mobilizations.

Bernard Marionnaud, Rassemblement Bleu Marine, Clamart, 2014.

The paradoxes of the symbolic economy of activism

The hypothesis concerning the rewards of activism was in the past and still has today iconoclastic and heretical connotations among activists, albeit less pronounced than before. By extension, this is also true in certain academic circles. Resistance appears beneath theoretical objections. The analysis of rewards is held to be partial and biased. It arguably neglects other dimensions of activism, such as “the constitution of identifying communities”18, passions, emotions, and affects19, or the joy of self-sacrifice. It is said to fit into a narrow utilitarian and Machiavellian anthropology, and to adopt the simplistic view of a calculating “homo economicus"20. These objections, however, are based on gaps in understanding the symbolic economy of activism, and on more or less interested misunderstandings21.

Conscious calculation or scotomization of appropriations in practice

The deliberate search for benefits associated with activism exists. It may have developed recently due to various transformations that will be discussed below. Today members of political parties may explain their party membership by the desire to find a job or to have a career in politics. But this relationship to activist engagement should not be generalized. It has in fact been criticized within activist spheres in which we can now indeed observe an opposition between “disinterested” voluntary behavior and overtly instrumental strategies22.

In the cases of “disinterested” commitment, the deliberate quest for gratifications is rare, and it is even less likely to be systematic. Rewards are appropriated in the course and within the “logic” of activist practices. But they are not deliberately sought as such. Frederik G. Bailey rightly points out that “services rendered out of love are services which are not paid for, and in the true moral relationship, services given are their own rewards”23. A cause is a collective symbolic good. But, the struggle for it is a reward in itself. It is therefore an “incentive” reserved selectively for persons engaged in the struggle. Attachment to a cause and the satisfaction of defending one's convictions give meaning to the lives and activities of many activists. From their point of view, the other satisfactions go unnoticed or occur additionally, and incidentally. From this perspective, membership cannot be explained simply by the rational calculation of the chances of obtaining benefits. “Cynical” behavior does indeed exist in the activist world, and its frequency may be increasing. But it does not follow that all behavior is like this.

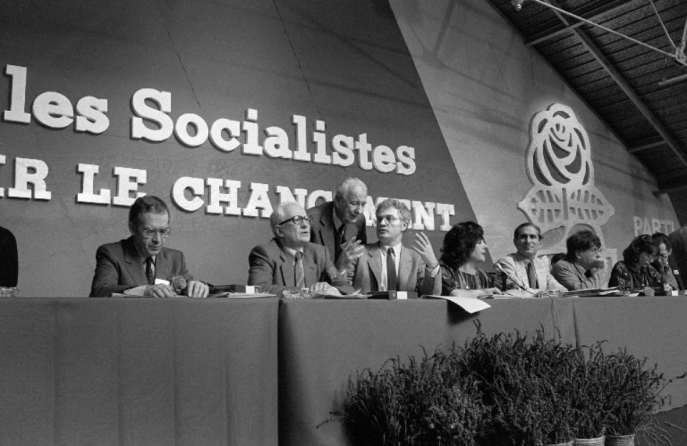

Congres of the french Socialist Party, Valence, 1981 ; Congres of the French Greens (Europe écologie-Les Verts), Pantin, 2016.

The states of “consciousness” (or, better, apperception, i.e. the process of blurred, incomplete, and ephemeral perceptions) of socially censored practices and representations, such as the rewards of activities, which are officially voluntary, are difficult to observe and describe. The appropriation of such rewards often takes place in practice, without any reflexive specification. It can be seen, for example, in the joyfulness of reunions, the cheerful atmosphere of meals which occur after such meetings, the meticulous arrangement of hierarchical orders on various occasions, the value given to being present on platforms at meetings, the distinction between sitting in the hall or being on the grandstand, or the excitement when organization members are appointed to positions of responsibility. These rewards are not only appreciated and, in some cases, envied, and coveted. They are partly, but minimally, “perceived”, or better still fleetingly noticed.

On the one hand, some activists do not see and do not want to see that their investments give rise to “rewards”, and even less do they want to see that their investments are supported by “rewards”. The appropriation of rewards can then be described as “unconscious”. However, in certain circumstances, activists may allude to the mechanisms of such rewards, for example when speaking “privately” or confidentially, or in interviews when activists recall the high points of their lives as activists, or possibly their disappointments and frustrations. Emphasis is then placed on interferences of personal considerations with commitments or struggles for internal power positions. They also refer to promotions, the performances of each other, the satisfactions drawn from some “feat”, or the joys of group endeavor. Whether it reflects greed or resentment, the evocation of activist memories provides material for objectifying the importance accorded in practice to the rewards attached to commitment. Such evocation is often allusive, and ironic. It may use half-embarrassed words, occur in undertones, or contain silences. The hypothesis that there are “unconscious” reward mechanisms is therefore as inadequate as the assumption of the deliberate pursuit of various benefits under the guise of voluntary commitment.

These two opposing relationships to activism exist and can be observed. Yet, it may be asked whether the most frequent behavior does not actually lie in a mix of these relationships, albeit a mix that may be more or less dominated by repression or recognition. In many cases, the rewards are at the same time censored, repressed, and denied, but also unclearly perceived and partially made explicit in certain circumstances. They are both present and absent in the subjective reasoning of activists. Activists can both demonstrate in practice and in narration the importance they attach to certain gratifications, and treat them as secondary or ridiculous when confronted with their explicit revelation. Some may resist sociological analysis and pay close attention to the polemical disclosure of interests related to engagement.

Scotomization, i.e. sliding from vague perceptions to the repression of uncomfortable memories, rather than “unconscious” behavior, perhaps best describes the alternative shifts of opposing perceptual pictures. It may be able to account better for the successive phases of denial and explicit recognition concerning rewards. Activists’ defenses may be relaxed in certain situations, for example in moments of exaltation or impulse, or, conversely, in times of finding oneself again or making confidences to close companions. Defensive behavior re-emerges as soon as contextual elements or excessively disturbing objectification encourages activists to return to more orthodox behavior. The work by Frederik G. Bailey can be used to understand such dualities. Bailey makes the distinction between “pragmatic rules” (favored by “contractual teams” that need to be followed for effectiveness, even if they are reprehensible), and “normative rules” (of honor among the “moral teams”, which require doing what is good and accepted by all). It can thus be assumed that the representations and the accounts given by activists are inseparably and inextricably “pragmatic” and “normative”. In varying proportions, they will change depending on organizations, the individuals, the moments in a career and historical contexts. The circumstances of activation lead to emphasis being placed on one or the other of these factors. Normative considerations seem to prevail in situations where it is necessary to assert or restore official representations, notably in the public arena, and during the “high” points in the life of a collective organization. In contrast, pragmatic factors appear to be more present in “private”, or in moments when activists let themselves go, take stock, confide, denigrate others, or are discouraged.

Such shifts in registers are possible because rewards are produced through supports to the ends of collective action. Activists derive satisfaction from their commitment because they invest in a cause. Adherence to a cause is therefore not independent and distinct from activists’ interests, with adherence being invoked to justify or obscure such interests. Instead, adherence to a cause is a component, which is intrinsically attached to everything that gives value to activism. The official purposes of collective action, as perceived by each participant, give meaning and value to rewards. Correlatively, when adherence to a cause becomes lukewarm, it quickly affects the flavor of the satisfactions that activists experience in supporting it.

Action against anti taxes paradises, collectif Faucheurs de chaises.

The effects of an activist’s career

Entry into activism follows an encounter between dispositions towards engagement and properties of situations that promote the activation of these dispositions. These include the chance encounters, the availability of new recruits, efforts to attract them, the attractiveness of the cause, and the benefits of membership that the new member discovers in the process of his or her engagement. These benefits may result from positive reactions by a new member’s entourage, the possibility of satisfying the demands of important friends and relatives, the consideration given by the group of peers to be joined, self-assertion in a new sphere, as well as the discovery of the joys and small pleasures linked to new activities.

Entry into activist life is not always, or is not only, governed by adherence to a collective cause and the desire to militate in its favor. Apart from a disposition to invest oneself in a specific activist endeavor, membership implies an availability that is often the result of independent biographical developments or incidents24. Activists themselves indicate, often in the course of their memories, how family, emotional, school, professional, activist disillusions or dissatisfactions, or even moving home, a divorce, retirement, health problems, or isolation encouraged them to join a collective organization. Membership is an investment in a new universe that is often correlative to a disinvestment in a competing sphere of life. This disinvestment may be individual and be part of an idiosyncratic path. Or, it may result from more general transformations and take on a more collective form when a class of individuals shares the dissatisfaction. This was the case, for example, of activist reconversions following a malaise felt by many teachers, or in the case of entry into social movements by workers facing contradictions stemming from their social advancement25.

Membership is a moment of official inauguration in an itinerary that can be analyzed as a career: i.e. as a path resulting from a set of interactions inscribed in structures and producing a sequence of events, experiences, positions, and points of view26. One of the characteristics of activist careers is that they often generate changes in perspective27. In the course of these processes, there may be signs of the strengthening or weakening of the reasons for joining the cause, the reinforcement of certainties or doubts, the discovery and appreciation of certain rewards or, conversely, the loss of appetite for what were previously the prized pleasures of commitment. The ways in which activists discover and come to appreciate the rewards of their activities are analogous to the learning of sensations in the career of a marijuana smoker, as analyzed by Howard Becker. From this perspective, it is important to integrate, and not contrast, the analysis of rewards, the question of emotions, self-sacrifice, and identifications with a collective movement.

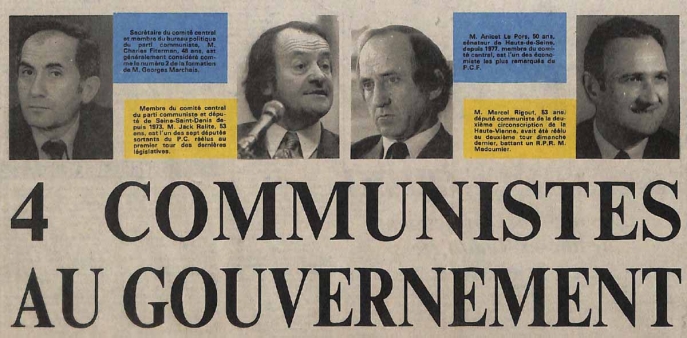

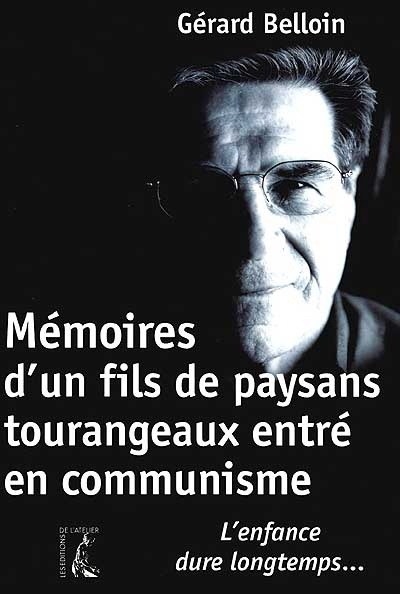

Activists’ careers are variable. The dispositions, availability and the sequence of circumstances lead some to enter into a lasting commitment. This may be accompanied by a reinforcement of the reasons for believing in a cause and sometimes also by the learning of the doctrinal principles and the mastery of a cognitive apparatus based on the collective ideology of the movement28. Explicit training at various levels may reinforce these diffuse educational effects29. The contribution of activism to the accumulation of activists’ cultural capital is all the stronger if they have fewer personal cultural resources, especially school capital. Members who were little involved in political issues at the time of joining can become politicized and acquire more or less developed elements of cognitive and statutory political competence in the course of their engagement30. This is how workers' movements attracted and selected leaders from the working class in the past, in contrast to the usual recruitment processes of political personnel.

Communists ministers, 1981.

In other career profiles, phases of investment, disinvestment, and sometimes reinvestment follow one another as interest fluctuates and with reconversions into competing areas of life. Changes in reasons for believing, interpretations of the cause, and the importance attached to the various gratifications of action at different moments of an activist’s career can be observed.

Changes in views and perspectives during the course of activists’ careers also show that the rewards of activism do not exist in themselves objectively. Instead, the various aspects of activists’ universe acquire the quality of being rewards, insofar as activists invest in some of them, and gradually derive satisfactions from them. The very same operating traits that stimulate investment by activists caught up in collective action may leave those who stay away indifferent. People who are very involved at some point in their itineraries may withdraw at other times. The value given to rewards and opportunities of obtaining them depend, for example, on the constraints and satisfactions of other “spheres” in an activist’s personal life. The value of the benefits derived from conviviality and community integration associated with activism vary, for example, depending on whether an activist has job or not, is single or has a family. The importance of professional constraints and even the very idea of professional constraints depend on the nature of an activist’s job and on the importance attached to it.

The “costs” of collective action

As with rewards, the costs of activist involvement do not present the objectivist character attributed to them by commentators astonished at the “paradoxes of collective action”. External observers or activists withdrawing from activism identify certain renouncements or risks. But for the most-engaged activists, these costs may be ignored, minimized, or perceived as bearable negative consequences, necessities, or even sacrifices of great significance. Likewise, investments have to be strong and underpinned by powerful attachment mechanisms, when activists engage in collective action with (“objective”) risks to their lives, to their family equilibriums, or to professional success.

In some situations, what external observers may be inclined to value as a “cost” is a source of satisfaction, bearing out the authenticity of commitment, in the eyes of the most ardent activists. Feelings of subjugation, renunciation, risk, deprivation, or sacrifice may dwindle and perhaps even disappear, for persons who do not have other investments to compete with their activism. When members are “wedded” to a cause or some form of collective action in its favor, as it is undoubtedly the case for some activists in times of strong mobilization, engagement only brings satisfactions and incurs no costs.

In more routine situations, rewards have the property of encouraging activists to minimize the costs of their engagement. In contrast, subjectively negative aspects of an activist’s experience become more visible, when “reward mechanisms” weaken, or when the value of rewards is eroded. In extreme cases, activism entails only disadvantages, subjections, risks, losses of time or constraints, when the reasons for investment disappear.

Nuit debout: of the mobilization in its routinization / repression.

It is undoubtedly at this moment that the retrospective perception an activist has of his or her career is the most detached from the official normative representations. It is the moment when rewards are explicitly stated, when pragmatic considerations prevail, when strong denigration may lead to biased and simplistic accounts of the past, which ignore the beliefs and satisfactions that were previously derived from commitment to a cause earlier held to be just. It is perhaps during various intermediate configurations, when an activist’s convictions “cool” and disinvestment emerges, that a minimal evaluation of both costs and rewards emerges. But this does not mean that the activist is carrying out an explicit or systematic cost-benefit analysis. When faith in the cause is less intense and commitment less “wedded”, some activists begin to count their time and measure their participation. Commitment may then rely more on distinct reward mechanisms that come from defending a cause. In such situations, notions of the reward and the cost of engagement do have a certain affinity with the fleeting, subjective perceptions of activists. Hence they are relevant to explanation and understanding. Yet, these notions clash more with activists’ common sense, as it is expressed while being “wedded” to the cause. They remain appropriate as explanations when the body of hypotheses that mobilizes them incorporates an analysis of the conditions of their (in)appropriateness for the understanding of activists’ subjective experience.

The specificities of organizations and potential rewards

Each organization or social movement is characterized by one or more “operating styles”, because of its ideological leanings, the characteristics of its members (age, cultural level, social backgrounds, tastes and ways of being), as well as its modes of organization and action. These ways of doing and being in a collective way are likely to be appropriated and invested by the members. They function as reward mechanisms, but at the same time as ways of selection. For example, the nature of internal debates will be more “intellectual” if a significant proportion of the members has been through higher education and if their ideological and political leanings are more intellectualized. The “theoretical” leanings of the debates will attract people who value the exchange of views about current affairs. Yet they will also deter other members who see such discussions as being idle, or who may feel overwhelmed by them. Persons who value spending a relaxing moment with friends will appreciate more casual meetings over a drink. Yet such socializing may elicit sarcastic responses by activists favoring political debate.

Organizations or movements attract and retain individuals who are inclined to value all or many of the rewards their actions are likely to generate. Members of such organizations who have different preferences will be indifferent to or even deterred by such rewards31. It follows that the hold exercised by a collective organization on members depends on the adjustments between the dispositions and the expectations of its members on the one hand, and the structure of rewards or of potential gratifications offered on the other hand. In the past, “workers’ parties” were thus able to succeed in attracting and keeping activists from popular and intellectual backgrounds in their ranks, because they provided a fairly wide range of rewards associated with their various internal segmentations. The general training and educational opportunities opened up by the French Communist Party's network of “schools”, at certain moments in its history, favored the attachment of activists who are aware of their educational shortcomings and who are anxious to access a legitimate culture32. In the same way, the possibilities of social ascension opened by this party at certain times satisfied expectations of upward mobility linked to feelings of “social downgrading” felt by some of the Party’s permanent staff33. The varied memberships of parties, unions, and associations, and differences between them, can therefore be enlightened by the differential rewards they provide through their operating modes.

Bernard Pudal, “La beauté de la mort communiste”, Revue française de science politique, n° 5-6, 2002, p. 545- 559.

The structured supply of reward opportunities within a movement changes over time. It is transformed with the course of history, changes in ideological leanings, internal organization and composition, as well as the relative position of an organization in the fields it is competing in. Thus, the growth and rise of a party, combined with the enlargement of its social representativeness, its notoriety, its institutional base, and media recognition, modify its style of functioning. As it becomes established in the political field, a political party offers positions of increasing value. It needs to recruit at the same time as it is able to attract collaborators, experts, specialists, and titled personalities. Simultaneously, it distances or marginalizes members endowed with less personal resources34.

The attractiveness of causes

The value attributed to rewards also depends on the relative attractiveness of the cause to be defended. Parties, unions, and specialized associations are in competition with each other, and also with other organizational types, without mentioning competition between activist investments and other social investments. The decline in party membership over the last decades is linked to a weakening of the beliefs in the significance of politics, whose multiple causes are too long to discuss here35. Losses in membership have led to transfers of personal investments by members, away from parties towards their private life “spheres”. They have also sometimes led to reconversions of partisan activism towards certain areas of the voluntary sector.

The (non-monetary and non-market) economy of investments and benefits that underpins collective action recedes when adherence to a cause declines36. Rewards from a given cause generate satisfaction precisely because activists believe in the value and significance of the cause (this is true, for example, of holding positions of internal power which leads pride). As defined by each participant, a cause gives meaning to all rewards that reinforce the inclinations of being committed to it. Investment in a cause stemming from collective action is indeed a condition of the possibility of rewarding activism.

Normative and theoretical conclusions

The existence of rewards for activism is a sociological hypothesis. It provides instruments of moving away from spontaneous explanations of activism, which are often naive and partial. This sociological hypothesis is a central component of a set of theoretical proposals that accounts for activist investments in collective action. These hypotheses do not seek to belittle or disparage collective commitments. On the contrary, they make it possible to understand better the conditions that allow for such commitments and those that contribute to their weakening. It is of course possible to question the effects of disenchantment that could result from these hypotheses spreading beyond the academic circles. However, it would make them more important than they really are, to assert that they have contributed to the ebbing of collective commitment, whose causes are many and largely external to the work of the social sciences. To the extent that “enchantment” actually persists, activists in fact know how to find and mobilize the resources of denial. Some activists – presumably few – may have been shaken by the “realistic” analyzes of the social sciences. This however is probably less because of any intrinsic disclosure effect than because of interests to the disclosure associated with disinvestment in collective action. From a normative point of view, it should be asked why an “enchanted” practice that is “blind” to the conditions of its enchantment would be preferable to more lucid investments. It can even be argued that for activism, lucidity and “authenticity” could be complimentary.

The sociology of the rewards of activism is a contribution to the sociological analysis of the relative autonomy of politics. Parties are enterprises of interest. They take charge of “external” social interests, for example those of their followers, which are also those of their members. However, they do so within the logic and limits of their own interests. The activists are stakeholders in these enterprises of interests. Taking into account the rewards of activism is, in this sense, a generalization of the theory of politics following Weber. Activists participate in the work of parties, but within the logic and limits of the rewards they obtain.

These reward mechanisms also contribute to the various social attachments of parties. Given the types of rewards they are able to generate, parties attract and attach women and men from defined backgrounds. In doing so, they contribute to consolidating their relations with these milieus37. In the past, workers’ parties were able to recruit and train activists from working class backgrounds, thanks to these various reward “mechanisms”. Parties favored the promotion of these members and succeeded in diversifying the social origins of political elites. They were able to provide a minimal resistance to the sociological “law” that rulers must come from the dominant social milieus. For a complex set of reasons, these reward mechanisms have weakened considerably. At the same time, workers’ activism has dried up and the links between these parties and their old social bases have eroded. Analyzing the rewards of activism is not denigrating voluntary commitment. Instead, it reveals the wonders of a spontaneous form of political engineering, whose potential has been somewhat lost and deserves to be restored.

Notes

1

Daniel Gaxie, Les Professionnels de la politique, Paris, PUF, 1973.

2

See especially Karl Marx, Le 18 Brumaire de Louis Bonaparte, Paris, Ed. Sociales, 1963 and Les Luttes de classes en France 1848-1850, Paris, Ed. Sociales, 1967.

3

Seymour M.Lipset, Stein Rokkan, Cleavage Structures, Party Systems, and voter Alignments: An Introduction, in Seymour M.Lipset, Stein Rokkan, Party Systems and Voter Alignments: Cross National [international] Perspectives, New York, The Free Press, 1967, p. 1-64.

4

Joseph Schumpeter, Capitalisme, socialisme et démocratie, Paris, Payot, 1967, p. 385.

5

Max Weber, Le Savant et le politique, Paris, Plon, 1959.

6

Max Weber, Economy and Society, Berkeley and Los Angeles, University of California Press, 1978, p. 55.

7

Max Weber, Économie et société, Paris, Plon, 1971, p. 55. For Weber, an “enterprise” is a particular type of social activity. When he refers to political or hierocratic enterprises, he is not resorting to analogy, and even less to the mobilisation of economic “metaphors”. Like political and hierocratic enterprises, economic enterprises are, according to Weber’s theoretical construction, particular types of continuous activities aimed at a finality, which make up a certain category of social activity.

8

Max Weber, Le Savant et le politique, Paris, Plon, 1959, p. 149.

9

Jacques Ion, La fin des militants?, Paris, Les éditions de l'Atelier, 1997; Rémi Lefebvre, “Le militantisme socialiste n'est plus ce qu'il n'a jamais été. Modèle de l'engagement distancié et transformations du militantisme au parti socialiste”, Politix, vol. 2, n° 102, 2013, p. 7-33; Isabelle Lacroix, “C'est du vingt-quatre heures sur vingt-quatre. Les ressorts de l'engagement dans la cause basque en France”, Politix, vol. 2, n° 102, 2013, p. 35-61.

10

Pierre Bourdieu, Raisons pratiques. Sur la théorie de l'action, Paris, Seuil, 1994, p. 164.

11

Max Weber, Le Savant et le politique, Paris, Plon, 1959, p. 124.

12

Max Weber, Le Savant et le politique, Paris, Plon, 1959, p. 156.

13

Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action. Public Goods and the Theory of Groups [1965], Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 1974.

14

Daniel Gaxie, “Économie des partis et rétributions du militantisme” , Revue française de science politique, vol. 27, n° 1, février 1977, p. 123- 154.

15

Annie Collovald, “Pour une sociologie des carrières morales et des dévouements militants”, in Annie Collovald (dir.), L'humanitaire ou le management des dévouements. Enquête sur un militantisme de “solidarité internationale” en faveur du Tiers-Monde, Rennes, PUR, 2002, p. 177-229.

16

For inforamtion on this, see, the examples analyzed by Cécile Péchu, “Les générations militantes à Droit au logement”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 51, 2001, n° 1-2, p. 73-103.

17

Such as doctors who work for humanitarian causes, analyzed by Johanna Siméant, “Entrer, rester en humanitaire. Des fondateurs de Médecins sans frontières aux membres actuels des ONG médicales françaises”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 51, 2001, n° 1-2, p. 47-72.

18

Alessandro Pizzorno, “Sur la rationalité du choix démocratique”, in Pierre Birnbaum, Jean Leca (dir.), Sur l'individualisme, Paris, Presses FNSP, 1986, p. 352.

19

Philippe Braud, L'Émotion en politique, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 1996; Christophe Traïni, Émotions… Mobilisation, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 2009.

20

Philippe Corcuff, “Les usages utilitaristes de la sociologie de Pierre Bourdieu dans la science politique française”, Revue suisse de science politique, vol. 8, n° 2, 2002, p. 133-143.

21

Daniel Gaxie, “Rétributions du militantisme et paradoxes de l'action collective”, Revue suisse de science politique, vol. 11, n° 1, 2005, p. 157-188.

22

Martin Baloge, Les Critiques de l'institution partisane des militants socialistes, Paris, Université de Paris 1, 2010.

23

Frederik G. Bailey, Les Règles du jeu politique, Paris, P.U.F, [1969] 1971, p. 58.

24

On this, Johanna Siméant shows how humanitarian activism appeals especially to persons with a taste for risk and community life for several reasons. These include a Catholic socialisation in large families, being a Scout in youth, and having frequented “total” institutions. See Johanna Siméant, “Entrer, rester en humanitaire. Des fondateurs de Médecins sans frontières aux membres actuels des ONG médicales françaises”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 51, n° 1-2, 2001, p. 47-72.

25

Bernard Pudal, Prendre parti. Pour une sociologie historique du PCF, Paris, Presses FNSP, 1989.

26

Howard S. Becker, Outsiders. Études de sociologie de la déviance [1963], Paris, Métailié, 1985.

27

Olivier Fillieule, “Propositions pour une analyse processuelle de l'engagement individuel. Post scriptum”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 51, n° 1-2, 2001, p. 199-215; Olivier Fillieule (dir.), Le Désengagement militant, Paris, Belin, 2005.

28

Daniel Gaxie, Le Cens caché. Inégalités culturelles et ségrégation politique, Paris, Le Seuil, [1978] 1993.

29

Nathalie Ethuin, “De l'idéologisation de l'engagement communiste. Fragments d'une enquête sur les écoles du PCF (1970-1990)”, Politix, vol. 16, n° 63, 2003, p. 145-168.

30

Daniel Gaxie, Le Cens caché. Inégalités culturelles et ségrégation politique, Paris, Le Seuil, [1978] 1993.

31

Cécile Péchu analyses interesting examples of activists in a housing association for people in difficulty. These activists joined the voluntary sector after leaving France's Socialist Party. One of them explained the multifaceted unease he felt within this party. He mentioned his relationship to language and his personal speech difficulties, which kept him out of internal confrontations, his lack of taste for power struggles, and the lack of interest that members of his section had for the problems of immigrants that were dear to him and for which he wished to promote political involvement. See “Les générations militantes à Droit au logement”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 51, n° 1-2, 2001, p. 82.

32

Nathalie Ethuin, “De l'idéologisation de l'engagement communiste. Fragments d'une enquête sur les écoles du PCF (1970-1990)”, Politix, vol. 16, n° 63, 2003, p. 145-168.

33

Bernard Pudal, “Le désengagement de Gérard Belloin: de l'engagement communiste à l'auto-analyse», in O. Fillieule (dir.), Le Désengagement militant, Paris, Belin, 2005, p. 155-169.

34

See the example of the Socialist Party analyzed by Rémi Lefebvre, Le Socialisme saisi par l'institution municipale (des années 1880 aux années 1980). Jeux d'échelles, Lille, Université de Lille 2, PhD dissertation, 2001.

35

Daniel Gaxie, “Les critiques profanes de la politique. Enchantements, désenchantements, ré-enchantements”, in Jean-Louis Briquet, Philippe Garraud (dir.), Juger la politique, Rennes, PUR, 2001, p. 17-240 ; “Sur l'humeur politique maussade des démocraties représentatives”, in Oscar Mazzoleni, ed., La Politica allo specchi. Istituzioni, partecipazione e formazione alla cittadinanza, Bellinzona, Giampiero Casagrande editore, 2003, p. 109-136 ; “Plus ça va, moins j'y crois à la politique. Adhésions et pertes d'adhésion cycliques au politique”, in SPEL, Les Sens du vote. Une enquête sociologique (France 2011-2014), Rennes, PUR, 2016, p. 179-194.

36

This is without doubt one of the reasons that favoured the transformations of relationships to collective action and the emergence of more calculated commitments, some of which may be overly instrumental.

37

In this sense, Frédéric Sawicki, Les Réseaux du Parti socialiste. Sociologie d'un milieu partisan, Paris, Belin, 1997.

Bibliographie

Martin Baloge, Les Critiques de l'institution partisane des militants socialistes, Paris, Université de Paris 1, 2010.

Frederik G. Bailey, Les Règles du jeu politique, Paris, PUF, [1969] 1971.

Howard S. Becker, Outsiders Études de sociologie de la déviance [1963], Paris, Métailié, 1985.

Pierre Bourdieu, Raisons pratiques. Sur la théorie de l'action, Paris, Le Seuil, 1994.

Philippe Braud, L’Émotion en politique, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 1996.

Annie Collovald, “Pour une sociologie des carrières morales et des dévouements militants”, in A. Collovald, M.-H. Lechien, S. Rozier, L. Willemez (dir.), L’Humanitaire ou le management des dévouements. Enquête sur un militantisme de “solidarité internationale” en faveur du Tiers-Monde, Rennes, PUR, 2002, p. 177-229.

Philippe Corcuff, “Les usages utilitaristes de la sociologie de Pierre Bourdieu dans la science politique française”, Revue suisse de science politique, vol. 8, n° 2, 2002, p. 133-143.

Nathalie Ethuin, “De l'idéologisation de l'engagement communiste. Fragments d'une enquête sur les écoles du PCF (1970-1990)”, Politix, n° 63, 2003, p. 145-168.

Olivier Fillieule, “Propositions pour une analyse processuelle de l'engagement individuel. Post scriptum”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 51, n° 1-2, 2001, p. 199-215.

Olivier Fillieule (dir.), Le Désengagement militant, Paris, Belin, 2005.

Daniel Gaxie, Les Professionnels de la politique, Paris, PUF, 1973.

Daniel Gaxie, “Économie des partis et rétributions du militantisme”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 27, n° 1, 1977, p. 123-154.

Daniel Gaxie, Le Cens caché. Inégalités culturelles et ségrégation politique, Paris, Le Seuil, [1978] 1993.

Daniel Gaxie, “Les critiques profanes de la politique. Enchantements, désenchantements, ré-enchantements”, in J.-L. Briquet, P. Garraud (dir.), Juger la politique, Rennes, PUR, 2001, p. 217-240.

Daniel Gaxie, “Sur l’humeur politique maussade des démocraties représentatives”, in O. Mazzoleni (dir.), La Politica allo specchi. Istituzioni, partecipazione e formazione alla cittadinanza, Bellinzona, Giampiero Casagrande editore, 2003, p. 109-136.

Daniel Gaxie, “Rétributions du militantisme et paradoxes de l'action collective”, Revue suisse de science politique, vol. 11, n° 1, 2005, p. 157-188.

Daniel Gaxie, “‘Plus ça va, moins j’y crois à la politique’. Adhésions et pertes d’adhésion cycliques au politique”, in SPEL, Les Sens du vote. Une enquête sociologique (France 2011-2014), Rennes, PUR, 2016, p. 179-194.

Jacques Ion, La Fin des militants?, Paris, Éditions de l'Atelier, 1997.

Isabelle Lacroix, “‘C'est du vingt-quatre heures sur vingt-quatre’. Les ressorts de l'engagement dans la cause basque en France”, Politix, n° 102, 2013, p. 35-61.

Rémi Lefebvre, Le Socialisme saisi par l’institution municipale (des années 1880 aux années 1980). Jeux d'échelles, Lille, Université de Lille II, PhD. dissertation, 2001.

Rémi Lefebvre, “Le militantisme socialiste n’est plus ce qu’il n’a jamais été. Modèle de ‘l’engagement distancié’ et transformations du militantisme au parti socialiste”, Politix, n° 102, 2013, p. 7-33.

Seymour M. Lipset, Stein Rokkan, Party Systems and Voter Alignments. Cross-National Perspectives, New York, The Free Press, 1967.

Karl Marx, Le 18 Brumaire de Louis Bonaparte, Paris, Éditions sociales, 1963.

Karl Marx, Les Luttes de classes en France. 1848-1850, Paris, Éditions sociales, 1967.

Mancur Olson, The Logic of Collective Action. Public Goods and the Theory of Groups [1965], Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1974.

Cécile Péchu, “Les générations militantes à Droit au logement”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 51, n° 1-2, 2001, p. 73-103.

Alessandro Pizzorno, “Sur la rationalité du choix démocratique”, in P. Birnbaum, J. Leca (dir.), Sur l'individualisme, Paris, Presses de la FNSP, 1986.

Bernard Pudal, Prendre parti. Pour une sociologie historique du PCF, Paris, Presses de la FNSP, 1989.

Bernard Pudal, “Le désengagement de Gérard Belloin: de l'engagement communiste à ‘l'auto-analyse’”, in O. Fillieule (dir.), Le Désengagement militant, Paris, Belin, 2005, p. 155-169.

Frédéric Sawicki, Les Réseaux du Parti socialiste. Sociologie d'un milieu partisan, Paris, Belin, 1997.

Jospeh Schumpeter, Capitalisme, socialisme et démocratie, Paris, Payot, 1967.

Johanna Siméant, “Entrer, rester en humanitaire. Des fondateurs de Médecins sans frontières aux membres actuels des ONG médicales françaises”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 51, n° 1-2, 2001, p. 47-72.

Christophe Traïni, Émotions… Mobilisation, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 2009.

Max Weber, Le Savant et le politique, Paris, Plon, 1959.

Max Weber, Économie et société, Paris, Plon, 1971.