From photograph to icon

The Lascaux cave paintings, Picasso’s Guernica, Robert Capa’s falling soldier, Marc Riboud’s photo of a young student with a flower defying the rifles of the US National Guard in front of the Pentagon on October 21, 1967, that of a young naked girl fleeing the Napalm bombardment of Vietnam on June 8, 19721, the TV images and then the photos of Neil Armstrong walking on the moon, those of “tank man” on Tienanmen Square in 1989 – all these images are now part of the collective memory of the citizens of a connected world. In the history of the French Republic too, certain images have more evocative power than others. Eugène Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People, for instance, which has come to symbolize the Republic, and whose two main figures, Liberty – since assimilated to Marianne – and the boy combatant, Gavroche, have gone on to have lives of their own2. More recently, one could think of the photo of De Gaulle sitting before a microphone in London on June 18, 1940, or that of François Mitterrand holding a rose at the Panthéon in May 1981.

Poster of the Jaurès contemporain exhibition, 2014.

The collection of documents on display in the Jaurès contemporain exhibition, held at the Panthéon in 2014, showed that, ever since his assassination in 1914, the great Socialist orator has always been present, to varying degrees, in the debates animating the left and French society more generally. Images play a major part in this national memory, a construct that is maintained and added to. Visitors arriving at the Panthéon were greeted by a large-format reproduction of Branger’s famous photograph, taken on May 25, 1913, at a meeting protesting against the three-year law, which sought to add an additional year to military service. For the Section française de l'Internationale ouvrière (the SFIO, the forerunner of the French Parti Socialiste) and its leader, Jean Jaurès, such a step only added to the risk of war. Branger photographed the rostrum from a distance. Above an immense crowd Jaurès grasps the pole of an unfurled red flag, the full force of his conviction clear to see.

This photo has since become iconic, and is no doubt one of the most frequently used images of Jaurès nowadays, but this was not always the case. Several photojournalists were present that day, and Jaurès was photographed at various moments during his speech. So why this particular image? Where and when was it published for the first time? What does it tell us about Jaurès? How has it been reused? Why has it stuck in our minds and taken precedence over others? Why and when did it become iconic? What can it tell us about the use of images in a world awash in pictures? Before answering these questions, the constituent parts of the image need contextualizing, for they have been interpreted in different ways depending on the period of the viewer3.

Jean Jaurès at Le Pré-Saint-Gervais, on May, 25th, 1913 by Maurice-Louis Branger.

The left’s symbols and images

This photo is a visual representation of Jaurès. The gesture and attitude depicted coincide with the mental image people have of Jaurès the orator. It is also one of the images that could be used to illustrate Jaurès the pacifist4. The various photos, paintings, drawings, and caricatures emphasize the range of representations associated with Jean Jaurès: the martyr for peace, the pacifist, the republican, the great orator, the socialist, the unifier of the socialists, the philosopher, or for his adversaries – particularly as shown in caricatures – the demagogue, the traitor, and the ‘Boche’.

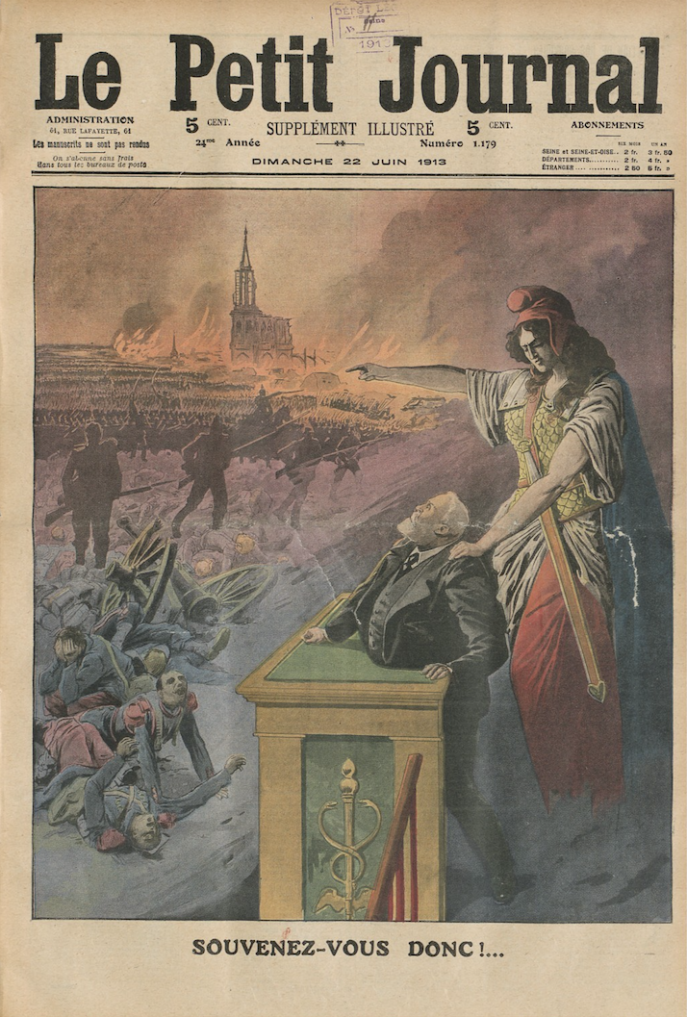

Le Petit Journal, June 22, 1913, one month after the meeting at Le Pré-Saint-Gervais, “Souvenez-vous donc !”. Marianne exhorts remembrance, alluding to the loss of Alsace during the 1870 war against Prussia, here symbolized by Strasbourg Cathedral in ruins.

These iconographic representations need to be placed in the universe whence they come if we are to properly understand them.

Images – just like symbols (flags, colors, emblems, logos, and songs) – play an important part in the history of the left, as well as in protest movements and the culture of organizations. They build up links between peoples and identify political families. Understanding the genealogy of these images and symbols can inform us about the state of the group that has produced, mobilized, or abandoned them5.

These images of Jaurès – those that still speak to us today – are part of socialist history and culture.

The French Republic has its tricolor flag, its motto, its anthem, its embodiment in the figure of Marianne, or the Sower, or the Gallic rooster, all examples of what Pierre Nora has called “sites of memory”. From 1848 onwards, the “reds”, together with the libertarians and anarchists, have built up their own symbolic universe, a mix of revolutionary and republican culture. This cultural syncretism still exists today, though in fainter form. Let us briefly examine the left’s main objects and how they have changed over time:

- a red flag6;

- an anthem, Pottier and Degeyter’s The Internationale, and then since 1977, for the socialists, Changer la vie7, together with a re-appropriation of La Marseillaise since the 1980s;

- the songs accompanying the labor movement: Le temps des cerises, Gloire au 17e, La jeune garde (culture communiste), Bandera rossa, Au devant de la vie;

- its mottos, slogans, and watchwords: “prolétaire de tous les pays” (workers of all the world), “Pain, paix, liberté” (bread, peace, freedom), “changer la vie” (change life), “Nos vies valent plus que leur profit” (our lives are worth more than their profits), and “l’humain d’abord” (people come first);

- its great historical moments: the Enlightenment, the French Revolution, the 19th-century revolutions, the Paris Commune, the Front Populaire, May 10, 1981;

- its pantheon of great men (plus a few women) to have marked French history: Voltaire, Rousseau, Robespierre, Danton, Saint-Just, Proudhon, Louise Michel, Guesde, Jaurès, Vaillant, Blum, Mendès France, Mitterrand;

- its insignia and logos: for the various communist formations, the hammer and sickle; for the socialists, the image of a rising sun with Marianne as a working woman (as opposed to the bourgeois Marianne), then the three arrows, and nowadays the fist and rose;

- its flower (the dog rose, wild rose, lily of the valley, and then the rose since the 1970s).

These symbols form the left’s collective memory. Flicking through the left’s illustrated albums shows how evocative and emotive they are. These images identify, illustrate, and characterize events that they bring to life. They are faithful and seductive, yet highly reductive. Photography holds a special place within this imaginary, for it brings groups together and reflects shared identities. Photography may also mislead if cropped, edited, colored, or taken out of context. A shot only reconstitutes a part of reality, and being technically imprisoned within its framing and focal length only presents the photographer’s viewpoint. Lastly, it should be remembered that once printed, sold, and published, a photo may well be cropped and a caption added, either to relay the photographer’s message or else to interpret or distort it. Photos thus need analyzing and deciphering with the rigor used when working with archival material.

Maurice-Louis Branger, a photojournalist at Le Pré-Saint-Gervais, May 25, 1913

On May 25, 1913, the SFIO held a protest against the three-year law at Le Pré-Saint-Gervais, a municipality where it had recently won control of the town hall8.The call to demonstrate and final recommendations from the organizers (the Seine Socialist Federation) were printed on the back page of that day’s edition of L’Humanité, the socialist newspaper run by Jaurès. No fewer than fourteen platforms were set up on the hill known as the Butte Rouge9, on each of which four or five speakers were programmed to address the crowd for up to fifteen minutes. Although accounts of the meeting rarely mention it, five women pacifists and socialist activists also spoke that day10. They were of no interest to the photographers.

A crowd of nearly 4000 people gathered around the platform where Jaurès was due to speak11. Just prior to going up onto the platform, Jaurès, wearing his tricolor sash, had listened to his comrade and friend Paul Renaudel, assistant editor on L’Humanité, and then the deputy for the Seine, Arthur Groussier, followed by a railwayman by the name of Toulouse who had been fired after the 1910 strikes. All three remained sitting in the cart used as a platform and listened to Jaurès, as caught for eternity by the photographer Maurice-Louis Branger (1874-1950)12. While Jaurès spoke, Branger took fifteen photos of him13. One of them was the distance shot that went on to become iconic14, symbolizing that day’s events and Jaurés’s action15.

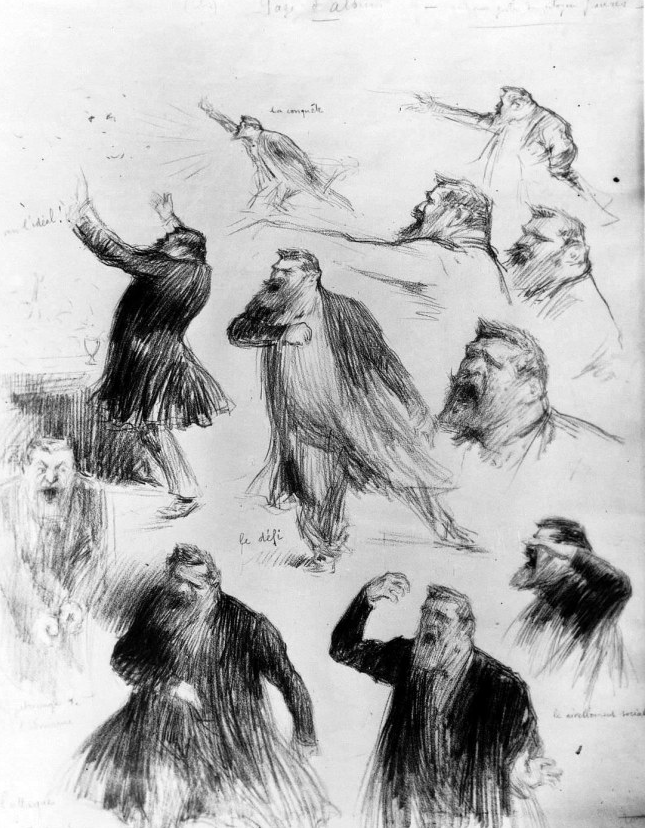

Returning to Branger’s coverage of that day, the series of shots he took allows us to trace his steps around the Butte Rouge. For though the iconic photo was taken from a distance so as to provide a wide shot of the speaker and crowds, the other fourteen we have examined were taken from the foot of the platform and centered on Jaurès in low-angle shots. Observing this set of photos brings out the particular attention Branger paid to Jaurès’s movements and gestures. Apparently captivated by his energy, he sought to catch his movements, providing a snapshot of his gestures and gaze. It is as if he were seeking to freeze and reproduce Jaurès’s poses, depicted by sketchers, painters, and caricaturists such as Léandre and Éloy-Vincent, who endeavored to seize the extraordinary range of attitudes Jaurès could convey16. By 1913 the verbal and gestural talents of the “great orator” were well known. Jaurès was a good photographic subject.

Jaurès à la tribune, sketches by Charles Léandre (1903).

The cameras of the period were now capable of freezing instants, provided the photographer perfectly mastered the technique (stabilizing the equipment, gauging the light, selecting viewing angles, assessing the sensitivity of the photographic plate) and had a feeling for the moment. In shooting several phases of Jaurès’s address, Branger built up a sequence that is virtually cinematic. These fifteen images tell the story from the moment Jaurès stepped onto the platform to his apotheosis as the man above the crowd, both dominating and forming one with it. Grasping the billowing red flag, Jaurès is leaning slightly forward, as if he wanted to speak into the ear of each listener come to hear him denounce a law that was threatening the peace. His upper arm stretched out and fingertips pressed together form a triangle, an arrowhead, symbolizing the socialist leader’s characteristic determination. For his supporters he was a teacher seeking to win over by force of argument, explanation of the facts, and rigorous analysis. There is nothing of the demagogue or diaphanous political leader about him. Branger was there to seize Jaurès in action. His photos became the definitive representation of the event, especially as there is no film nor sound archive of this speech.

Let us rapidly situate this photo among the larger set of photos of contemporary socialists.

A 19th-century photographic chamber, held at Toulouse Museum.

The price of equipment, together with the conditions for taking and developing photos, meant that in the late nineteenth century photography was still restricted to professionals and a small circle of amateurs. However, by the Belle-Époque it was starting to be taken up more widely. Technical advances now made it possible to produce pictures rapidly – in less than a day as of 1910 – and photos were becoming a very popular means of propaganda, advertising, and way of illustrating family events, demonstrations, and party conventions. In 1912 socialist convention-goers were able to buy souvenir cards of their national gathering17. These photographic postcards were better than engravings or drawings, and helped to make the faces of socialist leaders known to the people18.

Going to the photographer became a rite for families wishing to send news to acquaintances, friends, and relatives. Henri Manuel was one of the first photographers to build up a clientele of politicians, while Nadar established his more artistic renown in the world of culture, even though politicians were also keen to come and pose in his studio.

Photography was progressing, but, other than identity portraits, the vast majority of images diffused by the SFIO were of crowds. Photographers snapped impersonal groups of activists in the open air, on demonstrations, in convention rooms, or on leaving a meeting. These were the images the socialist press promoted to illustrate political events. In her study of photos published in L’Humanitébefore 1914, Annick Bonnet notes that only three of the thirteen were portraits. At the 1907 convention, apart from two portraits (of Guesde and Bracke), all the photos show rooms, delegates leaving, or demonstrations. Few show the convention platform or speakers. Nor did L’Humanitéplace its director in the limelight. The editors chose rather to show the mass making up the party, with the SFIO depicted in its activist collegiality. The Encyclopédie socialiste19 by Compère-Morel contains reproductions of convention postcards illustrating the great moments in the life of the party. Many volumes have identity photos of political and administrative leaders, journalists, and elected SFIO politicians, but none of the leaders in action or on the platform.

The destiny of one photo: from the front page to oblivion and back again

Document 1: L'Humanité, May, 26, 1913. Maurice Louis Branger's photograph appears on the front page, in the center, in a smaller size than the two others directly beneath the headline.

Document 2: L'Illustration, May, 31, 1913.

Document 3: Cover of Marcelle Auclair's book, La Vie de Jaurès.

Let us return to Branger and L’Humanité. Given the context, the role photos played in the party political press at that time, and the editorial choices of L’Humanité, it is not surprising that our photo shared the front page on May 26 with four others (document 1). It is not given any particular prominence, and even comes third, beneath two other shots showing the dense crowd gathered at the meeting the day before, published side-by-side across three columns. The banner headline “Barthou est-il satisfait?” (Is Barthou satisfied?) is followed by the subtitle “150 000 manifestants au Pré-Saint-Gervais” (150,000 demonstrators at Le Pré-Saint-Gervais), with these two photos as proof (the caption insists on “the demonstration at Le Pré-Saint-Gervais”)20. The photo of Jaurès is published unaltered, across two columns, and slightly cropped (with the top two thirds of the flag out of the frame), in a smaller panoramic format than the original press print Branger doubtless sold to the editorial board of the socialist newspaper21 (as he no doubt offered his set of images to other newspapers that turned down this one). Underneath, on single columns, are the portraits of two other speakers, Brustlein, a Swiss federal councilor (to demonstrate the event’s international character) and Marcel Sembat, deputy for the Seine. Pride of place is given to the crowd, the people gathered there, with Jaurès being one of the speakers present – albeit a speaker named on the front page, accompanied by his photograph, no doubt because he was the most important. But without excessive deference.

One week later, on May 31, the same photo appeared in the large circulation magazine L’Illustration (document 2). This time, however, it was cropped to focus on Jaurès, and used to illustrate an article denouncing the protests against the three-year law22, with the image accompanied by a wholly unambiguous caption: “the demagogue”. The framing might suggest a desire to glorify the subject, but the political line of the magazine and content of the article rule out any such hypothesis. It is a matter of showing an isolated, aggressive man beneath the halo of a red flag (which invasively fills the frame in this cropped version), coloring the demagogic words of the socialist deputy. The crowd has disappeared, only a manipulator remains.

Our research has not turned up any other instances of this photo being used in the press in the weeks following the event or over the course of the following years. The articles published when Jaurès was assassinated and to mark the first anniversary of his death were illustrated solely with portraits and drawings, or else with other photographs (mainly posed portraits by Nadar, Henri Manuel, Branger, or else a 1911 photo taken at Montevideo). In 1916, the newspaper Les Hommes du jour published a photo by Branger of the May 25, 1913 meeting, but it was one of the low-angle shots from the foot of the platform. Equally, on November 23, 1924, when Jaurès was being transferred to the Panthéon, the Cartel des gauches newspaper, Le Quotidien, published two other photos from Branger’s coverage at Le Pré-Saint-Gervais23.

The first occasion we know of when the iconic image was reused dates from 1954, on the cover of Marcelle Auclair’s biography, La vie de Jaurès24 (document 3). It was in fact the cropped version of the photo published in L’Illustration, but this time associated with a positive vision of the subject, relaying his “pacifist” creed, thereby showing how a given photo may be used in very different ways25. In 1957 a school manual contained a color drawing of Jaurès speaking, but transposed to a mine in the Tarn with slag heaps and winches in the background. He is shown addressing a public of miners, hence of “workers”, but without any red flag (perhaps due to the school context), and wearing the tricolor sash that marks him out as a deputy. Nevertheless, what the authors of this popular image have focused on is the gesture and what it evokes.

Ten years later, to mark the fiftieth anniversary of his assassination, the SFIO’s national weekly, Démocratie 64, reproduced the photo, choosing to crop even more closely on Jaurès, cutting the red flag in half. That same year, the historians Annie Kriegel and Jean-Jacques Becker brought out their book 1914, la guerre et le mouvement ouvrier français26, with a photo taken on May 25, 1913 on one of the first pages. However, it was dated as 1912, as it also was in the catalogue published by the Musée Jean-Jaurès in Castres to mark the centenary of his birth in 1959. These approximations suggest that the Le Pré-Saint-Gervais demonstration did not yet hold a sufficiently important place in the collective memory for the photos documenting it to be well-known and identified. To the best of our knowledge, this dating error was not reproduced in the very many centenary publications in 2014, nearly all of which used the iconic photo this time round.

Document 4 : Cover of the magazine Historia published in 1969.

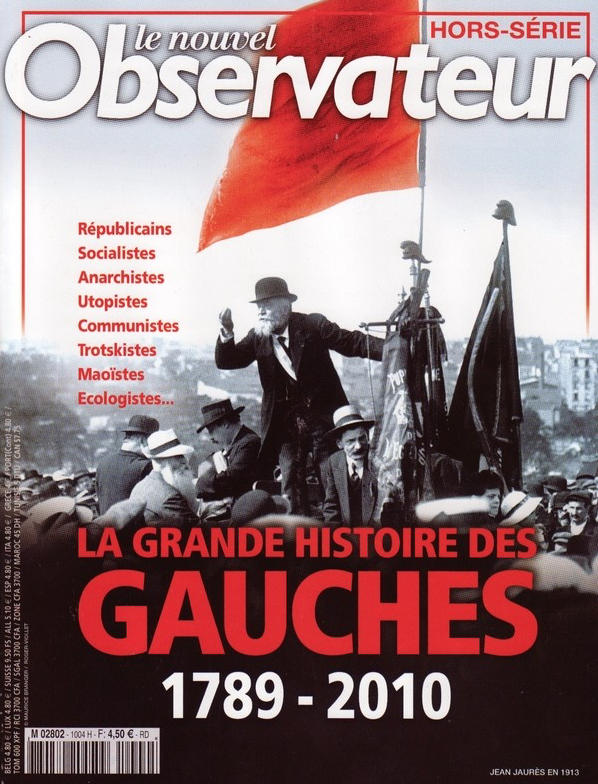

Document 5 : Cover of the magazine Le Nouvel Observateur published in 2010.

In 1969 the photo was promoted to the cover of the magazine Historia to illustratea dossier called “Jean Jaurès et l’Internationale”. The flag and the Phrygian caps on the poles of the two other flags attached to the makeshift platform were colored red, with the speaker being left in black and white27. In the early 1970s the image was being rediscovered. Sometimes the flag was recolored, and the image solarized, in tune with the aesthetic criteria of the editors of the period (documents 4 and 5).

In 1984 it was the Parti Communiste Français (PCF) that took up this photo to use on the cover of a Bulletin de propagande et d’information, in a bold montage designed by the Grapus communications agency. This large-format publication presented a full-page illustration of two repeating motifs, a blue triangle containing the photo of Jaurès at Le Pré-Saint-Gervais, alternating with rectangles in the form of TV screens showing the face of the PCF’s then general secretary, Georges Marchais.

The next year, the Société de bibliologie et de schématisation published Jaurès et ses images. The photo appeared on the cover, in the cropped version first used by L’Illustration. The commentary briefly noted that it was the “most widespread shot”, but of what28?

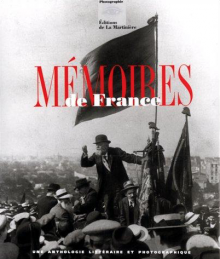

Document 6 : Cover of Jacques-Louis Delpal and Claire Julliard's book, Mémoires de France published by Éditions de la Martinière in 1998.

In 1991, a media milestone was reached with its publication on the cover of a literary and photographic anthology, Mémoires de France (Éditions de la Martinière) (document 6), with the reframing giving the impression that this fleeting moment lasted an eternity. This 1991 publication did not give the name of the photographer once again. Still, Branger’s photograph was becoming well-known.

The meaning and usages of an iconic image

The change in this photo’s status may be dated to the 1990s. That was when it became an emblematic image. Additional evidence of this was given in 1994, when the Société d’études jaurésiennes chose it to illustrate the cover of its quarterly Cahiers, to mark the eightieth anniversary of Jaurès’s assassination (retaining it on the cover until the publication was redesigned in 1997). By now it embodied the assassinated orator. It imposed its presence by the symbols it reunited – the red flag, the amassed crowd, the sky above and earth below, the martyr, the man above the crowd, and the apostles at his feet.

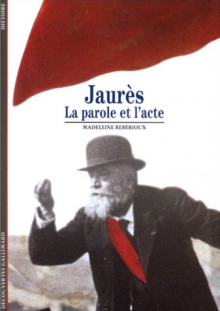

Document 7 : Cover of Madeleine Rébérioux's book Jaurès. La Parole et l'acte.

That same year the president of the Société, Madeleine Rebérioux, was readily convinced to publish a colored and very closely cropped version of the photo on the cover of her Jaurès. La parole et l’acte29(document 7).

The flag is in red, as is the tricolor sash that Jaurès wore that day, like all the elected politicians at the meeting. Rebérioux is an undisputed Jaurès specialist and chose, or at least tolerated, to present him in revolutionary garb, with the coloring presenting a more radical interpretation of his life. Is this alteration merely a matter of marketing, to simplify or clarify how to read this image30?

After this first instance of the sash being recolored, different versions were produced opposing those who saw Jaurès as a socialist and republican (with a tricolor sash) and those who wished to emphasize his socialist and revolutionary commitment, despite his having always ruled out this latter option, choosing to present himself as a reformer. In 2005, in its centenary year, the Parti socialiste followed suit in venturing to reinterpret history, recuperating Jaurès for its electoral campaign supporting the EU Constitutional Treaty, with a poster on which Jaurès’s red flag has been replaced by the stars of a European Union banner. Further examples could be given of the way the image has been manipulated and diverted from its original meaning. The same is true of Jaurès’s hand gesture, that of a teacher, fingertips touching in the act of demonstration, yet sometimes reinterpreted as a raised fist to emphasize his words to the crowd31. This anachronism – the raised fist only became a left-wing gesture in the 1930s – is ultimately not that important. It is precisely all these reframings, colorings, and reinterpretations which endow this image with its status as an “icon”.

Nowadays the many users of the photo clearly wish to celebrate Jaurès the pacifist. The context and event act as proof. This meeting against the three-year law, one year before the eruption of World War I, was clearly part of Jaurès’s combat to ward off the threat of war. It is but a short step from peace to pacifism. While this is not the place to discuss this interpretation of Jaurès’s politics, let us simply point out that he was a patriot, well informed about matters of national defense, and certainly no thoroughgoing pacifist32. The place, Le Pré-Saint-Gervais, the outlying district turning leftwards, had recently been won by the SFIO in a significant historic moment that bode well for the future. The central actor, Jaurès, is expressing the full force of his commitment to avoiding violent conflict. The famous well-loved orator is presented in majesty, in action, and as a future victim, a martyr to the cause for peace.

This photo thus acts as a response to the portraits published on his death, illustrating “the man, the thinker, socialist33”. It acquired its meaning retrospectively, bringing him back to life, resuscitating his sacrifice, recounting a moment with activists in the hope of saving the peace. This photo thus renders Jaurès to his people, amidst his people, as a man among others.

This photo, rediscovered in its full original form, may thus be used to tell several stories. Above and beyond its coloring for political or marketing purposes34, its multiple meanings make it intriguing despite its familiarity – as if despite the viewer seeking the truth the photo retained part of its mystery. It takes us back to a time when socialism was uncompromised by power. Jaurès embodied the hope for a different future, and his martyrdom adds to the emotional charge it has today. After the numerous revelations about the staging, montage, and falsification of images in politics and the arts, publishing this photo in its original format, without cropping, also shows the shift in historians’ and viewers’ relationship to photographic documents. The image has truly acquired the status of a source. A source that can no longer be toyed with.

Nowadays the success of Branger’s photo cannot be separated from the history of photography. Above and beyond the symbols that it mobilizes, with the flag proudly fluttering, it has become part of the illustrated catalogue of the history of the left, like the photo of the CGT activist, Rose Zehner, addressing her striking colleagues at the Citroën-Javel factories on March 23, 1938, caught for eternity by Willy Ronis. This history is far from consensual. Thus Jaurès’s posture may suggest the fervor of his commitment, or else betrayal by socialists, with the commitment to peace reaffirmed on May 25, 1913 standing in contrast to their subsequent rallying to the Union Sacrée. For some on the left, Jaurès’s act at Le Pré-Saint-Gervais, this communion with the assembled people, sits ill with the socialist deputies’ decision to “defend the Motherland” in August 1914 and work alongside the government. This goes some way to explaining why communists currently see a line of filiation to the figure of Jaurès and his thought, as evidenced by the PCF’s numerous tributes and multiple events dedicated to him. Despite its divergences, the left may look to its martyr and draw comfort. He was great. He sacrificed himself. Thanks to his image, the hope is still alive that another world was indeed possible.

Notes

1

Ce cliché de Nick Ut, où l’on voit Kim Phuc, enfant, victime d’un bombardement de l’aviation sud-vietnamienne a été pris le 8 juin 1972. Il est pourtant souvent associé au « moment 68 », pour symboliser l’horreur des bombardements américains sur le Vietnam.

2

Révolutionnaire dans l’histoire de la peinture avec son plan large et son personnage central, une femme drapeau à la main, ce tableau, daté de 1830, est une allégorie de la liberté. Enrôlé internationalement au service de toutes les causes et reproduit ou réinterprété sur tous types de supports, de l’affiche aux couvertures de disque, il « illustre » depuis près de deux siècles bien des événements (souvent la révolution de 1848).

3

Cette étude a pour origine l’exposition Jaurès contemporain conçue par Vincent Duclert qui interroge la « mémoire de Jaurès », depuis son assassinat le 31 juillet 1914, il y a 100 ans, et la trace qu’il a laissée dans le débat à gauche et plus largement dans la vie politique et culturelle nationale. Il a sélectionné dans nos collections les images, photographies, cartes postales, les brochures, livres et objets notamment un buste, qui pourraient illustrer son propos. Dans ce cadre, il nous a proposé de composer un panneau dont nous avons signé le texte, mais pas dirigé la mise en page, ni la sélection finale des images, autour de la célèbre photographie de Jaurès saisi en plein discours au Pré-Saint-Gervais, le 25 mai 1913 par le photographe Maurice-Louis Branger (1874-1950).

4

Il n’existe pas de banque de données des innombrables « images » de Jaurès (dessins, peintures, caricatures, photographies, bustes…) mais s’agissant des photographies, on peut estimer qu’il est présent sur près de 200 clichés différents. Un échantillon significatif est reproduit dans l’ouvrage de Jean-Noël Jeanneney, Jean Jaurès, Nathan, photo poche histoire, 2001. Dès 1959, le Musée Jaurès à Castres publiait un petit catalogue riche d'une iconographie diverse parmi lesquelles les photographies.

5

Les historiens s’intéressent de plus en plus aux symboles et aux images. Nous avons ici une pensée pour Maurice Agulhon récemment disparu, qui a su montrer à travers son œuvre et ses travaux sur Marianne, et ses recherches sur la symbolique républicaine, tout l’intérêt qu’il y a à observer la manière dont nos sociétés manient leurs symboles.

6

En 1936, le PCF adopte le drapeau tricolore qu’il « noue » avec le drapeau rouge soviétique (faucille et marteau, symboles adoptés aux lendemains de la Révolution bolchevique). Voir Maurice Dommanget, Histoire du drapeau rouge des origines à la guerre de 1939, Librairie de l’Étoile, 1967. Quant au PS, il garde son drapeau rouge même si, à partir de 1971, son nouveau symbole, le poing et la rose, lui associe également le rose comme couleur politique.

7

Robert Brécy, Florilège de la chanson révolutionnaire. De 1789 au Front populaire, Paris, Éditions ouvrières, 1990.

8

Deux mois auparavant, le 16 mars, la CGT, au moment du débat à la Chambre des députés, a rassemblé une foule de manifestants au Pré-Saint-Gervais. Le 25 mai, la SFIO a invité la confédération ouvrière à participer au rassemblement et autorise également la présence de groupements anarchistes et libertaires. Enfin, le 13 juillet 1913, Jaurès, au côté de sa fille Madeleine, participera au dernier meeting réuni en ce lieu avant la guerre. Voir Madeleine Rebérioux, « Le Pré-Saint-Gervais et Jaurès », in V. Perlès (dir.), Le Pré entre Paris et banlieue, histoire(s) du Pré-Saint-Gervais, Paris, Créaphis, 2005.

9

Elle est connue comme la butte-du-Chapeau-rouge au Pré Saint-Gervais.

10

Il s’agit de Suzanne Gibaud, Alice Jouenne, Élisabeth Renaud, Louise Saumoneau, Maria Verone. L’Humanité, 25 mai 1913.

11

D’après les rapports de police consultables aux Archives nationales, cote F 7/335. Les auteurs remercient Philippe Oulmont de leur avoir transmis cette cote d’archives. Nous renvoyons également à son article pionnier « Au Pré-Saint-Gervais, 25 mai 1913 : Jaurès en rouge et en tricolore », in V. Duclert, R. Fabre, P. Fridenson, Avenirs et avant-garde en France XIXe-XXe siècles. Hommage à Madeleine Rebérioux, Paris, La Découverte, 1999, p. 391-394.

12

Nous nous sommes intéressés à ce photographe longtemps oublié du crédit photographique et à l'histoire de ses photographies, en tentant de repérer les nombreuses utilisations, nous livrant à quelques interprétations sur ses usages partisans et, enfin, à l'histoire de leur acquisition par l'agence Roger-Viollet qui depuis le milieu des années 1960 en gère les droits de reproduction. Voir Éric Lafon, La Photographie de Jaurès, à paraître.

13

Nombre établi d’après le nombre de photographies de Branger que nous avons identifiées et recensées, parues dans des journaux, magazines et livres, de 1913 à nos jours.

14

Au sens de Christian Gattinoni, Les Mots de la photographie, Paris, Belin, 2004.

15

Madeleine Rebérioux, Jean Jaurès. La parole et l’acte, Paris, Gallimard, 1994.

16

Voir par exemple, Charles Léandre, « Jaurès à la tribune » (1903), Eloy-Vincent, « Croquis pour servir à illustrer l’histoire de l’éloquence » (1910), « Brillant match d’éloquence entre MM. Jean Jaurès et Jules Guesde » (1900), par Henri Somm, œuvres conservées aujourd’hui au musée Jean-Jaurès de Castres. Documents commentés par Alain Boscus.

17

À partir de 1904, le Parti socialiste de France édite quatre cartes postales de propagande : un portrait de Jules Guesde, un de Édouard Vaillant, et deux cartes avec un dessin illustrant le slogan « Organisons-nous ! ». Elles sont vendues 5 centimes pièce, et le parti leur fait de la publicité pour une vente militante dans sa presse. Après l’unité socialiste, en 1908, le parti socialiste SFIO diffuse via sa librairie douze cartes postales, des portraits : Des figures historiques, Marx, Blanqui, Jean-Baptiste Clément, Eugène Pottier, des chefs nationaux et régionaux du socialisme, Jaurès, Guesde, Allemane, Brousse, Delory, Landrin, Édouard Vaillant, Paul Lafargue. Toutes les familles sont représentées, le parti ne fait pas « personnalité ».

18

Jaurès est très présent à travers ce nouveau « média ». En 2000, à l’initiative de Remy Casals, le colloque Sur les pas de Jaurès (Privat, 2004) a étudié le corpus des cartes postales qui ont accompagnées les luttes de Jaurès aux quatre coins du territoire. Plus récemment, dans le cadre d’une journée d’étude organisée par la Société d’études jaurésiennes, Annick Bonnet a fait une communication sur les images des congrès de la SFIO entre 1905 et 1914 (Cahiers Jaurès, n° 187-188, 2008).

19

Compère-Morel, Jean-Lorris, Quillet, Encyclopédie socialiste, syndicale et coopérative de l'Internationale ouvrière, Paris, Aristide Quillet Éditeur, 1912.

20

Le quotidien socialiste ne fait pas sa une sur le discours de Jaurès, mais sur l’ampleur de la manifestation et son chiffrage. Le nombre de manifestants annoncé par L’Humanité est-il fiable ? Une note de la Sûreté nationale du 26 mai 1913 le minore, mais ne conteste pas le succès du rassemblement : « Chez les socialistes. La manifestation du Pré St Gervais. Les dirigeants du Parti socialiste se montrent très satisfaits du succès de la manifestation d’hier, et surtout de ce qu’aucun incident ne s’y est produit. De l’avis général, le nombre des assistants atteignait cent mille, et le chiffre des signatures recueillies pour le pétitionnement, qui n’était pas établi ce matin, est évalué à près de 30 000. […] À signaler également l’ovation qui a été faite à Vaillant et surtout à Jaurès ». Voir Archives nationales, F 7/335, Note de la Sûreté, M 54 U du 26 mai 1913.

21

À partir des renseignements fournis par Philippe Oulmont dans son étude déjà citée, nous avons consulté dans le fonds de la Sûreté nationale déposé aux Archives nationales un tirage de presse d’époque, tamponné Branger.

22

On peut lire dans ce numéro de L’Illustration que si les organisateurs annoncent 120 000 manifestants, « L’Humanité titre le lendemain sur 150 000 – la Préfecture de police n’en aurait compté que 30 à 35 000 ». Cependant, dans certains des rapports de police, le chiffre de 150 000 est aussi repris. Celui de cent mille également. Relevons enfin que le journaliste de L’Illustration note la présence imposante d’un drapeau noir des groupements anarchistes, souvent oubliés dans les comptes rendus de la presse.

23

Pour l’exposition au Panthéon, ces deux photographies ont été reproduites sur des dadzibao.

24

Marcelle Auclair, La Vie de Jaurès ou la France d’avant 1914, Paris, Le Seuil, 1954.

25

L’exemple le plus connu de tous étant l’Affiche rouge. Il s’agit à l’origine d’une affiche de propagande produite par les nazis pour dénoncer et stigmatiser la Résistance française. Elle est réutilisée « positivement » par cette même Résistance et la mémoire collective la range aujourd’hui dans le corpus des images les plus emblématiques de la lutte contre l’Occupant.

26

Annie Kriegel, Jean-Jacques Becker, 1914, La guerre et le mouvement ouvrier français Paris, Armand Colin, 1964.

27

On retrouvera cette même version de la photographie pour illustrer Jaurès, puis le socialisme ou les gauches successivement en couverture d’un numéro Les Grands événements du XXe siècle en 1983, puis d’un numéro du magazine Textes et documents pour la classe (TDC, 2004). En 2010, le magazine Le Nouvel Observateur publie un hors-série consacré à « L’Histoire des gauches 1789-2010 » et d’énumérer « Républicains, Socialistes, Anarchistes, Utopistes, Communistes, Trotskistes, Maoïstes, Ecologistes » sur la couverture affichant la photographie de Jaurès par Branger.

28

« Images et “images” de Jaurès », Marie-Claude Vettraino-Soulard, in Jaurès et ses images, Collectif, Société de Bibliologie et de schématisation, 1985.

29

Madeleine Rebérioux, Jaurès. La Parole et l'acte, Paris, Gallimard, 1994.

30

En 1999, on retrouve fort logiquement cette photographie (recadrée mais dans sa version originale en noir et blanc) en couverture de l'ouvrage Hommage à Madeleine Rebérioux. Jaurès. La parole et l'acte, Paris, Gallimard, 1994.

31

Le plus bel exemple de ce télescopage se trouve chez Paul Nizan qui, en 1938, dans La Conspiration, évoque « les images sentimentales que Paris gardait de Jean Jaurès et de son canotier et de sa vieille jaquette et de ses poings levés contre la guerre devant le grand ciel du Pré Saint-Gervais ». Nous en profitons pour signaler que l’on confond souvent les deux meetings du Pré-Saint-Gervais, celui de mai, où Jaurès porte un chapeau noir, et celui de Juillet, où il se protège du soleil avec un canotier blanc.

32

Dans l’abondante bibliographie sur ce thème, au-delà de la somme de ses récents biographes Gilles Candar et Vincent Duclert (Jaurès, Fayard, 2014), ou de la présentation de Jean-Jacques Becker à la réédition de « L’Armée nouvelle » dans l’Œuvre de Jaurès (Fayard, 2013), nous renvoyons à l’utile mise au point de François Chanet dans le numéro spécial de L’Histoire (n° 397, mars 2014) : « La paix, mais pas à tout prix ».

33

Nous reprenons ici le sous-titre de la première biographie de Jaurès publiée par Charles Rappoport, en 1916, aux éditions de l’Émancipatrice.

34

Du Nouvel observateur à L’Humanité dimanche, de L’Histoire à Historia, du Hors-série du Monde à L'Express ou à GéoHistoire pour n’évoquer que la presse et les magazines nationaux, les utilisations en couverture ou en pleine page sont fréquentes au cours des quinze dernières années. Nous ne donnons ici que quelques exemples de magazines parus en 2014.

Bibliographie

Marcelle Auclair, La Vie de Jaurès ou la France d’avant 1914, Paris, Le Seuil, 1954.

Jean-Jacques Becker, « L’Armée nouvelle » in L’Oeuvre de Jaurès, Paris, Fayard, 2013.

Annick Bonnet, « Images de congrès : les photographies des congrès socialistes (1905-1914) », in Cahiers Jaurès, n° 187-188 « Les Débuts de la SFIO », p. 47-61, 2008.

Robert Brécy, Florilège de la chanson révolutionnaire. De 1789 au Front Populaire, Paris, Éditions ouvrières, 1990.

Alain Boscus, Remy Cazals, Sur les pas de Jaurès : la France de 1900, Paris, Privat, 2004.

Gilles Candar, Vincent Duclert, Jaurès, Paris, Fayard, 2014.

Adéodat Compère-Morel, Jean Lorris, Encyclopédie socialiste, syndicale et coopérative de l’Internationale ouvrière, Paris, Aristide Quillet Éditeur, vol. 12, 1912.

Maurice Dommanget, Histoire du drapeau rouge des origines à la guerre de 1939, Paris, Éditions ouvrières, 1990.

Christian Gattinoni, Les Mots de la photographie, Paris, Belin, 2004.

Jean-Noël Jeanneney, Jean Jaurès, Paris, Nathan, Photo poche histoire, 2001.

Annie Kriegel, Jean-Jacques Becker, 1914, La guerre et le mouvement ouvrier français, Paris, Armand Colin, 1964.

Eric Lafon, La Photographie de Jaurès, à paraître.

Paul Nizan, La Conspiration, Paris, Gallimard, 1938.

Philippe Oulmont « Au-Pré-Saint-Gervais, 25 mai 1913 : Jaurès en rouge et en tricolore », in V. Duclert, R. Fabre, P. Fridenson, Avenir et avant-garde en France XIXe-XXe siècles. Hommage à Madeleine Rébérioux, Paris, La Découverte, 1999, p. 391-394.

Madeleine Rébérioux, Jean Jaurès. La Parole et l’acte, Paris, Gallimard, 1994.

Madeleine Rébérioux, « Le Pré-Saint-Gervais et Jaurès », in V. Perlès (dir.), Le Prè entre Paris et banlieue, Histoire(s) du Pré-Saint-Gervais, Paris, Créaphis, 2005.

Charles Rappoport, Jean Jaurès. L’homme, le penseur, le socialiste, Paris, Éditions de l’Émancipatrice, 1916.

Marie-Claude Vetttraino-Soulard, « Images et “images” de Jaurès » in Jaurès et ses images, Collectif, Société de Bibliologie et de schématisation, 1985.