August 4, 1789, the Estates General Hall in Versailles, 8 p.m.: the members of the National Assembly took their seats in the room. The meeting was to discuss a decree intended to restore order in provinces affected by peasant revolts. Right after the decree was read, the vicomte de Noailles stood up to propose a motion abolishing feudal rights and making seigneurial dues redeemable. The duc d’Aiguillon seconded this proposal. Three speakers from the Third Estate forcefully spoke out against feudal abuses. Their diatribes sparked indignant reactions on the benches of the nobility. The duc de Nemours (affiliated with the Third Estate) sought to refocus the debate on the decree that was on the order of business. A delegate from the nobility, the duc de Châtelet, took the floor to state that he approved the motions by de Noailles and d’Aiguillon, and that he personally relinquished all feudal rights over his domains. Straightaway, other deputies from the nobility publicly announced they renounced their rights or proposed the abolition of privileges. Displays of joy and enthusiasm followed. Members of the clergy declared that they divested themselves of their tithes. Representatives of towns, municipalities, and provinces in turn repealed corporate privileges. At about 2:30 a.m., the session was declared closed. The legal regime undergirding an estate-based society was dead1.

The French National Assembly: Meeting on the night of August 4, 1789.

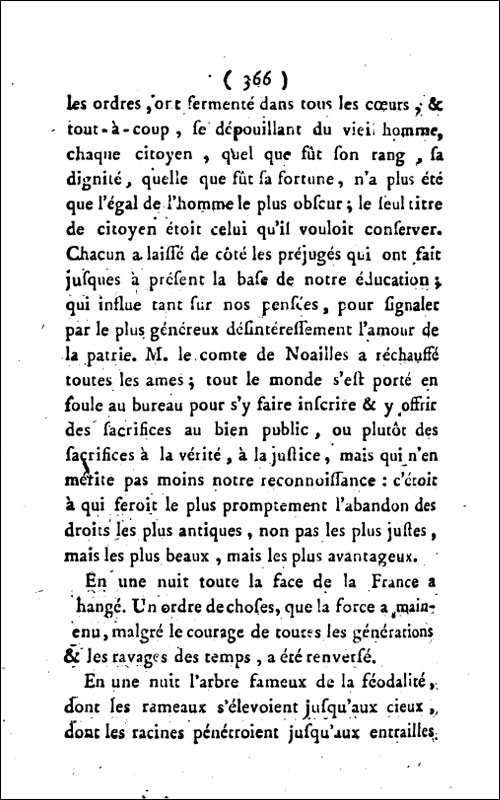

“It is known that [the nobility] itself committed suicide in the night of August 4. What remains unknown is how astounded the main protagonists of this revolution found themselves after the meeting. The duc de Biron noted as much, saying aloud with a laugh: ‘But what have we done, sirs? Is there anyone who knows?’” (Condorcet)2. The level of incredulity reflected the scope of the event. On August 4, 1789, the members of the privileged orders – the nobility and the clergy – carried out a general act of renunciation, whereby they relinquished the positions, the statuses, and the rights constitutive of their raison d’être.

Journal des États Généraux, meeting on August 4, 1789: “In one night was toppled the infamous tree of feudality, the branches of which reached up to the skies, the roots of which went all the way into the bowels of the earth … In one night was destroyed … feudal, aristocratic and parliamentary power”.

This act of renunciation furthermore signaled the end of a regime. In divesting themselves of their privileges, the delegates of the nobility and the clergy scuttled the institutional and legal framework grounding their domination. The “suicide” amounted to a “revolution”. “The night of August 4, 1789 [...] marks the moment when a juridical and social order, forged over centuries, composed of a hierarchy of separate orders, corps, and communities, and defined by privileges, somehow evaporated”3. Contemporaries were fully cognizant of this revolutionary character. In a letter dated August 8, 1789, Pinelle, a priest and deputy from Alsace, tersely observed:

we abolished the entire feudal regime and attendant rights4.

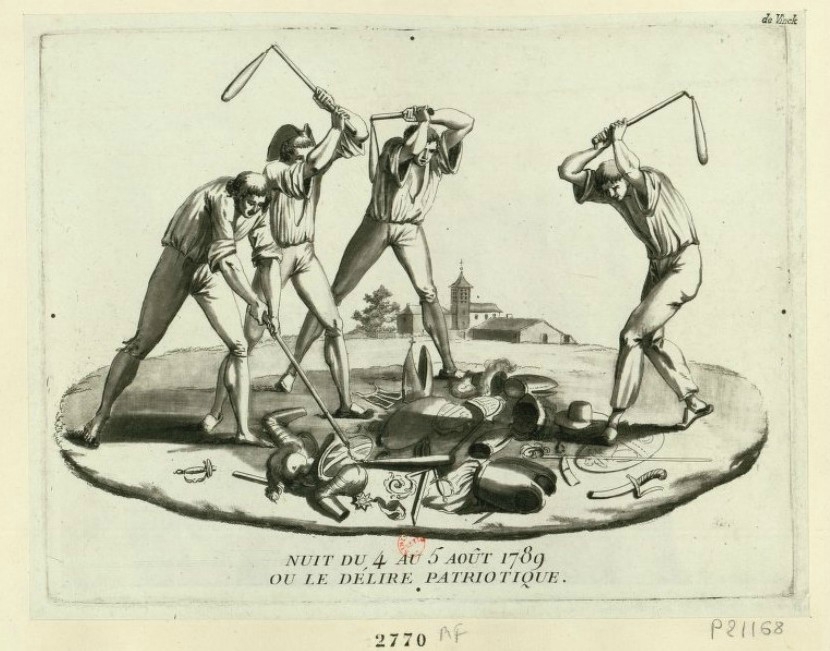

“Patriotic delirium”.

The night of August 4, 1789 therefore reveals and magnifies a fact that events less dramatic, spectacular, unexpected or confined in terms of time tend to obfuscate: moments of collective renunciation punctuate processes of regime collapse. They shape their dynamic and consequently their outcome. Analyses of political breaks miss the mark unless they take up the tools required to investigate collective abdication as a modality of breakdown.

Meeting of the Cortes, November 18, 1976: endorsement of the “Law for the Political Reform” (Ley para la Reforma Política).

“Law for the Political Reform”, November 18, 1976.

This point holds for very different types of political regimes. On August 4, 1789, the fate of an estate-based regime was at stake. In November 1976 in Spain, a dictatorship, buttressed by the hegemonic control of a single party undid itself, giving way to parliamentary democracy5. In 1989, Communist elites in Eastern Europe (Poland, Hungary, East Germany, Czechoslovakia) endorsed their own ousting6. Mention could also be made of regime transitions in South Africa (1990-1994) and the Soviet Union (1991)7.

Berlin, november 1989.

These events related to authoritarian and dictatorial regimes. It would be erroneous to suppose that democracies are exempt from such occurrences. On March 23, 1933 the Center Party delegation to the German parliament (the Reichstag) passed the “Law to Remedy the Distress of the People and the Reich” (Gesetz zur Behebung der Not von Volk und Reich), which sanctioned the constitutional death of the Weimar Republic. Similarly, the transfer of legislative, executive, and constituent powers to Marshal Pétain on July 10, 1940 marked the end of the French Third Republic8. The June 2, 1958 vote to confer a constitutional mandate on General de Gaulle is another case in point: the vote legalized the scuttling of the French Fourth Republic and the birth of a new regime9.

Reichstag, March 23, 1933.

Vichy, French National Assembly: Laval expounds the aims of the transfer of constitutional powers.

Let us make no mistake: acts of renunciation are not limited to political decision-makers and representative institutions. They are to be considered from the moment members of an “imaginary community”– that is, a collective entity with which people identify and affiliate themselves (a class, a religious group, a socio-professional group, a neighborhood, or a national community) – are confronted with a political offensive threatening their interests, collective integrity, or ability to act. The possibility of abdication is inherent to any situation imposing a challenge to a given group.

Le Temps, issue dated July 12, 1940.

Le Matin, issues dated July 11 and 12, 1940.

How then shall we account for this possibility? Common sense, with its proclivity for simple explanations, suggests three broad lines of reasoning. These provide generic arguments that regularly make their way in explanatory accounts. Because they reflect typical ways of making sense of politics, their underlying logic needs to be laid bare. The first line of argument imputes abdication to the experience of constraint. The decision is a case of force majeure. Actors cannot do otherwise. The second argument elevates misjudgment to the rank of primary cause. Group members are not fully aware of the ins and outs of their decision. They abdicate unwittingly. Their decision is a fool’s bargain. As for the third argument, it places ideological collusion at the center of the stage. Actors ratify their abdication because they view it as justified.

“The worker in the kingdom of the swastika” (electoral leaflet of the social-democratic party), July 1932.

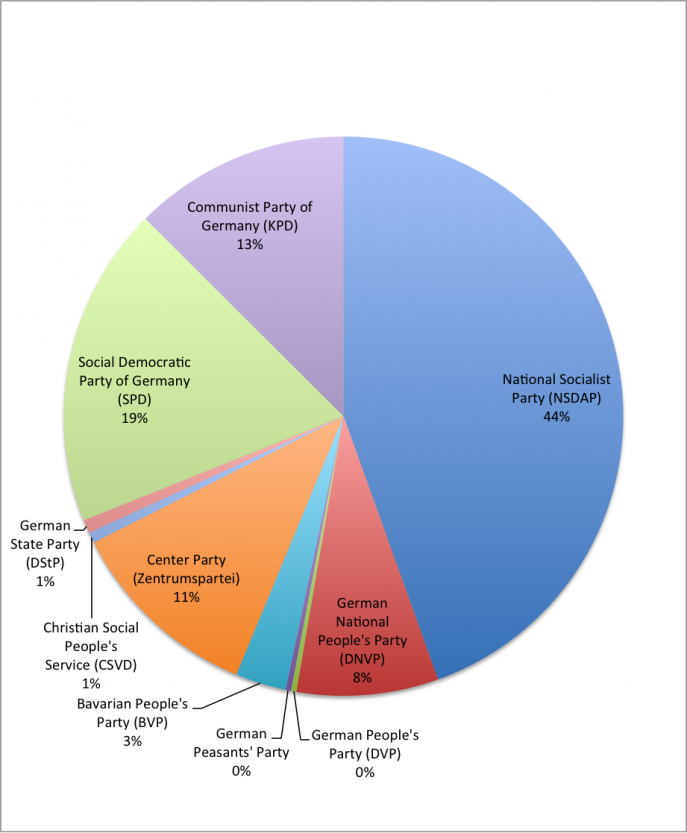

The following remarks subject each of these commonsense arguments to analytical and empirical scrutiny, taking as a reference point a test case that protagonists, essayists, and historians have alternatively interpreted according to these three lines of argument: the collapse of the Weimar Republic in March 1933. My focus will be on how the delegates of parties that until then had upheld the Weimar Republic reacted to Hitler’s political demands: the Center Party (Zentrumspartei), the German State Party (Deutsche Staatspartei, DStP), the Bavarian People’s Party (Bayerische Volkspartei, DVP), and the Social Democratic party of Germany (Sozialdemokratische Partei Deutschlands, SDP).

This choice of focus is deliberate. Because of their political ramifications, and the clarity with which they objectify the act of relinquishing rights and capacities, parliamentary votes, such as the vote of March 1933, stand out as striking instances of collective abdications. They make it possible to identify the groups involved and their members, the issues at stake, and the collective processes leading to the decision.

1. At first glance, the most obvious argument is one cast in terms of constraint: actors abdicate because they cannot do otherwise. There are two variants to this argument. One invokes coercion: constraint bears the mark of violence and the threat of reprisals. Actors give in to force or blackmail. The second variant refers to the pressure of the circumstances. Actors confront a situation such that they do not envisage any alternative. The structure of the choice they face makes their abdication ineluctable.

The Reichstag burns, February 27, 1933 – “The Reichstag burning. Let us crush Communism. Let us smash Social-democracy” – Debating chamber in the Reichstag, February 28, 1933.

Many accounts interpret the “legal revolution” of March 1933 along these lines as the consequence of Nazi violence. On January 30, 1933 Hitler was appointed chancellor (prime minister) at the head of a coalition government in which two Nazis held ministerial positions: Wilhelm Frick at the ministry of the interior, and Hermann Goering minister without portfolio. Imbued with a feeling of impunity, Nazi party activists attacked, threatened, and intimidated their opponents during and after the campaign for the parliamentary elections on March 5, 1933. They intended to have the upper hand, and they made it clear.

Poster of the Center party (Zentrumspartei), March 1933.

Parliamentary elections, March 5 1933, Germany.

Parliamentary elections, March 5, 1933: distribution of seats in the Reichstag.

On March 21, Hitler submitted a bill to parliament granting him full legislative and executive powers – including the power to alter the constitution – for a period of four years (the Enabling Act). For German democrats, approving this bill meant placing parliamentary democracy in the hands of its sworn enemies. In effect, this bill gave Hitler carte blanche to establish a dictatorial regime.

Since this bill opened the way to constitutional changes, it could not be passed without a constitutional majority composed of two thirds of the votes in parliament. The parties in the governing coalition (the Nazi party and the German National People's Party (Deutschnationale Volkspartei, DNVP) did not command such a majority. Yet, a constitutional majority of 444 votes passed the bill. The Center Party (Zentrum), the Bavarian People's Party (BVP), and the German State Party (DStP) voted in favor. The 94 SPD social democratic deputies present in Berlin were the only ones to vote against. The Communist deputies, who were in hiding or in jail, did not vote.

Clearly, the vote of March 23, 1933 took place under the shadow of violence. On the day of the vote (March 23, 1933), a crowd of Nazi activists demonstrated outside the Kroll Opera, where parliament was meeting (the fire at the Reichstag building in the night of February 27, 1933 had destroyed the plenary hall):

We want full powers. Otherwise there will be trouble!

Hence, the claim that the deputies who granted Hitler full powers would not have done so without the pressure brought to bear by the Nazis seems obvious10. Yet, this claim obfuscates more than it reveals, for two reasons. First, threats and blackmail do not necessarily yield subservience. Consider the stance taken by the deputies of the Social Democratic Party (SPD) in March 1933.

The SPD members were particularly liable to Nazi violence, more so than their peers from the Center Party. On March 23, however, all the SPD deputies who could attend the session voted against transferring full powers to Hitler. It would be mistaken to argue that these deputies had nothing left to lose. While in the eyes of the Nazis the fate of those whom they identified as “Jews” could not be negotiated, the matter was different for non-Jews. Some in the SPD considered a vote of abstention as a way to preserve the prospect of a modus vivendi11.

Instances of collective behavior, such as the stance of the SPD delegation to the Reichstag in March 1933, that contradict the constraint argument point out its incomplete and problematic character. In some cases threat and intimidation have no hold over those whose behavior they seek to fashion. A systematic explanation should be able to account for these negative cases and their possibility.

Second – and this point complements the first one – we should not suppose that situational constraints exert their effects of their own accord. These constraints have no “objectivity” per se. Rather, their “objectivity” is refracted through the interpretive and normative frames that actors targeted by violence adopt to make sense of the situation. The behavioral impact of these frames is all the greater as actors believe that they enjoy consensus12. By way of consequence, situations that, from the standpoint of an external observer, are equivalent in terms of constraints turn out to yield contrasted collective behaviors.

2. Whereas the constraint argument entails a motivational interpretation of abdication, which points to fear or resignation as the main motivations at play, the invocation of miscalculation, on the other hand, shifts the emphasis to the informational and cognitive aspects of the process. Two variants of this argument need to be distinguished. The first variant invokes ignorance. Actors are unable to correctly assess the consequences of their decisions. They do not have the information required for sound judgment. The second variant emphasizes deception. Stakeholders were given assurances that once the power transfer is effectuated, power would be exerted within defined limits. These assurances were not fulfilled.

Oskar Farny, a Center Party deputy in March 1933, deployed this sort of argument in his response to the denazification questionnaire he was requested to fill up after the war:

In 1933, no one knew which direction Hitler was going to follow after having taken over power: his programmatic statement was moderate and full of appeasing assurances about domestic and foreign issues. At this point in time, no one could imagine that the [German] people had fallen into the hands of a swindler and liar of such historical proportion13.

As noted in an editorial of Der gerade Weg (The right path) dated March 1, 1933, Nazi leaders can hardly be accused of concealing their objectives14. They pilloried democracy with open scorn. If they played the game of democratic elections, it was solely to undermine them. The legality of the means they employed served revolutionary objectives. Hitler in person made this point clear on September 25, 1930, at a Supreme Court (Staatsgerichtshof) trial of three officers charged with high treason on the grounds that they belonged to the Nazi party. The party's tactic, he stated, was to legally acquire state power. While this tactical choice differed from attempts to take power through coups in the 1920s, the objective was the same, namely overthrowing the Weimar Republic15.

Der gerade Weg (The right path): March 3, 1933 issue, leading article p. 3: “The positive Catholic casts a principled vote” (“Der positive Katholik wählt grundsätzlich”).

In February-March 1933, there could be no doubt as to the Nazis’ drive for political monopoly and exclusive control of the state apparatus. In a February 12 speech, Eugen Bolz, at the time prime minister of the state of Württemberg and Center party delegate to the Reichstag, denounced the Nazis’ conception of state power.

They are looking for a new state law. They formulate a new concept of the state, one that says: the state can do anything and is entitled to do anything. The individual is nothing and means nothing. […] This is a doctrine that stands in absolute contradiction with natural law, with our Christian views. That is why we want from the outset to react against this concept of the state and this exacerbation of state power16.

The diagnostic is straightforward: the Nazis’ exercise of state power reflected a totalitarian conception. Ludwig Kaas reiterated this denunciation in early March in a speech delivered in Cologne:

Everything gets monopolized […] But we shall never tolerate that Germany fall under the monopoly of one party. Nor shall we tolerate that opposition to this truly unjustified aspiration for monopoly be defamed17.

Der gerade Weg (The right path): February 23, 1933 issue, p. 7: “No! No! No Catholic can vote for the National Socialists” (“Nein! Nein! Kein Katholik darf nationalsozialistisch wählen”).

Particularly revealing is the fact that in addition to public declarations by prominent Center Party members, internal Center party documents and sources revealing exchanges between deputies also pointed out the danger of totalitarianism. In the Center Party's bulletin of February 24, Ludwig Kaas pointed out the risk of a Nazi dictatorship18. At the beginning of March 1933, a “strictly confidential” 4-page memo intended for the Center party cadres referred to the fate of the Catholic party in Fascist Italy, and to rumors that the Center party would be subsequently eliminated19.

Eugen Bolz, prime minster of the state of Württemberg (June 1928 – March 1933) and Center Party delegate to the Reichstag (1919-1933).

The argument of miscalculation thus lacks credibility. Non-Nazi politicians in March 1933 were fully aware of the Nazis' ultimate goals. They knew how Hitler and his affiliates intended to exercise state power. The claim of misinformation has no ground. Were some parliamentarians mistaken about the consequences and meaning of their vote, their misperception should rather be interpreted as a case of voluntary blindness.

Against the miscalculation argument, two further objections of broad analytical significance need to be underscored. The first one points to the connection between actors’ awareness of the stakes and their search for information. As they look for relevant information allowing them to minimize the risks they take, self-delusion becomes more difficult. The second objection points to the public character of the decision. When the choice is public, actors know that somehow they will be held accountable. Self-delusion again proves to be a much more arduous task than when the choice remains confined to the private sphere.

This is not to say that once actors have made their decision, they will not strive to come to terms with it by providing themselves with “good” reasons for their action – “good” in the sense that these reasons provide the basis for collective justification. Acquiescence actually tends to produce the knowledge that fits it – that is, the knowledge that truncates, sugar-coats, or glosses over information at odds with the choice made. In these instances, misjudgment does not determine choice. Rather, choice determines misjudgment20.

3. Let us now consider the third explanation: ideological collusion. Here abdication results from a lack of conviction. The members of the group are predisposed to relinquish some, or all, of their rights, possessions, or capacities. They may even grant credence to their critics’ denunciations. The fruit falls because it is a ripe. Vilfredo Pareto views the circulation of elites in this light. A governing group abdicates without offering any opposition when it no longer believes in itself, or when it takes up the watchwords of its adversaries21.

This explanation is present in accounts of the collapse of Communist regimes in 198922. It also feeds analyses of the vote of the Center Party parliamentary delegation on March 23, 1933: the Center Party endorsed Hitler’s enabling bill because they were not truly committed to parliamentary democracy. Their ideology lent too far towards a reactionary, hierarchical, and corporatist vision of society. Hence, they indulged in the idea of finding common grounds with the Nazis23.

Like the explanation in terms of force majeure, an explanation cast in terms of collusion implies a prevalent motivational schema. Whereas invoking coercion or the pressure of the circumstances posits individuals who feel powerless and act out of resignation or fear, invoking collusion depicts actors who placidly accept their own dispossession or welcome it. Their abdication rests on an act of adherence whether this act is low key or in plain view.

At odds with this interpretation are behaviors and attitudes revealing a decisional dilemma: ambivalence, oscillation, a wait-and-see stance, a desire for anonymity and a subsequent feeling of guilt or remorse. Collusion is scarcely compatible with uncertainty and ambivalence. Witness the hesitations and matters of conscience confronting the Center Party deputies ahead of the vote. In a meeting of the Center Party parliamentary delegation taking place on the morning of March 23, Heinrich Brüning, prime minister from 1930 to 1932, described the Enabling Act as “the most monstrous thing that has ever been requested from a parliament”24. The afternoon meeting on the same day before the deputies cast their ballot took a dramatic turn. Writing to Brüning shortly afterwards, Friedrich Dessauer evokes “one of the most difficult [decisions he] ever had to make in his life”25.

Friedrich Dessauer, Center Party delegate to the Reichstag (1924-1933) – Heinrich Brüning, prime minister in 1930-1932, Center Party delegate to the Reichstag (1924-1933).

4. What do we learn from this critical overview of commonsensical explanations? Three points are worth underscoring. First, a systematic explanatory framework should be able to shed light on positive and on negative cases. That is, it should be able to explain acts of collective abdication as well as acts of collective resistance in the face of challenge. This requirement is of particular importance with regard to the argument of constraint. Coercion is no warrant of its intended effect. When experienced as an intolerable attack on an individual's or a group's integrity, it can become a motive for opposition and refusal.

Second, whether we are considering resistance or abdication, uniform behavior does not necessarily stem from uniform dispositions or beliefs. Like any collective act, abdication makes individual actors alike by virtue of their behavior. In some cases, the production of a shared collective narrative after the event bolsters this uniformity. Yet, without prior examination, we cannot conclude that actors adopted a similar course of action because they were made of the same fabric.

Third, abdication implies making a choice. Analyzing its modalities requires analyzing it as a choice-making process26. As we examine this process at close range, actors’ indecision and uncertainty come forward. Confronted with a situation that threatens their rights, identity, power, or welfare, they waver. The group under challenge finds itself at a crossroads. It can disaggregate, abdicate, or resist.

Christine Teusch, Center Party delegate to the Reichstag (1924-1933) – Helene Weber, Center Party delegate to the Reichstag (1924-1933) – Joseph Wirth, Center party delegate to the Reichstag, prime minister in 1921-1922 and minister of home affairs in 1930-1931.

In the meeting of the Center party delegation that took place in the afternoon of March 23, 1933, Christine Teusch, Helene Weber and Joseph Wirth declared themselves opposed to the tranfer of full powers to Hitler.

Some individuals defect because they believe jumping ship is a good bet or because they do not identify with the group in the line of fire. Still others do not view any course of action other than opposition as acceptable. Between these two poles, heteronomy – i.e., allowing others to determine one's choice – prevails amidst varying dispositions and expectations. Uncommitted actors await the signal or the injunction that will put an end to their indeterminacy. The paradox is that this expectation insofar as it is shared, far from offering a way out, makes the group the locus of an open choice, a vanishing point without any definite content.

The remark by Ludwig Kaas, chairman of the Center Party, during a meeting of the parliamentary delegation on March 23, 1933 before the vote, is telling in this regard:

No one can take the responsibility of casting an isolated vote. This responsibility is too heavy – the vote needs to be depersonalized27.

In other words: whichever course of action we take, we have to align with one another so that our stance be unanimous. Given the risks and stakes involved, Kaas stated the need for collective alignment.

To say that the members of a group do not intend to individually expose themselves in a challenging situation is to say that they share an interest in aligning their behavior with one another’s. The challenge elicits on their part the desire to be subsumed in a collective decision that, since it is collective, absolves them to a certain extent. It also motivates them to appropriate the reasons that subsequently will provide the thread of a justifying narrative.

Two scenarios are then possible. The first is a behavioral cascade. Some group members publicly commit themselves to a course of action. Their involvement tips individuals who otherwise would have remained on the sidelines. These in turn tip other group members, and so on and so forth. Alignment is sequential28. The second scenario rests on a process of expectation formation. In the absence of sequential alignment, actors seek to anticipate the behavior of the group as a whole. They form their expectations either by informally exchanging information about their action preferences (“local knowledge”), or by considering how public events – events supposedly known to all – will affect the group (“tacit alignment”). Alignment occurs by anticipation29.

This explanatory schema grants a central place to the heterogeneity of dispositions and motivations. Because of this heterogeneity alignment has a temporality of its own. Individual propensities to conform to the mold vary. Given what is at stake, some protagonists act autonomously, without regard for the stance adopted by others. Most decide to make themselves indistinguishable from a collective stance.

5. Let us now go back to the night of August 4, 1789, with which this examination of abdication and regime collapse opened. Contemporaneous accounts stress the collective outburst of joy. The event is thus exceptional in three respects: because of its unexpected character – the about-turn took place in a very short period of time and without any forewarning –, because of the scale of the renunciation, and because of its emotional content. Joy and euphoria stood in sharp contrast to the antagonisms voiced in the preceding weeks.

This joyful effusion is all the more surprising when attention is paid to the context: peasant revolts were rocking several provinces. “[Insurgents] were aiming at the destruction of feudal oppression. At times, they were also aiming to take revenge on a seigneur or a person of privilege against whom they harbored particular grievances”30. Throughout the month of July, news of castles being sacked reached the deputies gathered in Versailles31. For the aristocratic delegates, these pieces of news were particularly worrisome. The decree motivating the night session on August 4 reasserted the “sacred rights of ownership” and denounced “disruptions and violence” as “serving the criminal projects of the enemies of the public good”. Its intent was repressive32.

Given these contextual elements it is hardly surprising that authors who reflected on the event interpreted the outpouring of joy that accompanied the resolutions passed on the night of August 4 as an instance of irrational group behavior: unforeseeable, devoid of any apparent logic, and based on a ratcheting up of emulation. Only the force of collective effervescence, it seems, can account for such a puzzling decision.

Le Bon and Freud laid the premises of this reading. From their perspective, collective situations characterized by a high density of interpersonal relations are particularly prone to mimetic and contagious moves33. Once these dynamics are in motion, actors lose control. Their affects take the lead as they get enmeshed in a “circular reaction” (Herbert Blumer) whereby individuals become at once the receptacles and the relays of affective states they cannot control. Mimicking each other, actors are incapable of a strategic assessment of consequences34. In a consonant vein, Durkheim interpreted August 4, 1789 as a moment of collective effusion in which adhesion to the group took precedence over any other consideration, motivating individuals to transcend egotistic interests35.

The Elementary Forms of Religious Life, 1912.

Seen in this light, the night of August 4 has all the trappings of a typical case. The delegates renounced their privileges in a state of general ebullience. The comte of Lally-Tolendal did not fail to observe it in a note he handed to the chair of the assembly, Isaac Le Chapelier, during the debate:

no one is in control of himself. Close the session (“Levez la séance”)36.

Renunciations and calls for reform rained down as if avoiding being outdone in sacrifice was now the priority. Subsequently, protagonists evoked a sort of “delirium”.

While the emotional dimension of the event is quite obvious, the role played by enthusiasm in this collective dynamic remains open to question. On this issue, two remarks are in order. First, the fact that protagonists were overwhelmed by joy tells us nothing about the process that brought this effusion about. Second, the exact role played by emotions in the etiology of abdication remains to be elucidated. In this respect, the night of August 4 provides a privileged field for inquiry.

A detailed sequential analysis of the event shows that effusion and ebullience were not bound to happen. Indignant reactions to the diatribes against feudal abuses at the beginning of the meeting indicate that the resurgence of antagonisms belonged to the realm of the possible. As we narrow down the focus, it appears that effusion occurred in the wake of Châtelet’s declaration and that it was preceded by a moment of uncertainty among the deputies of the nobility. The nodal point lies in the conjunction of collective hesitancy and a public statement37.

6. To recapitulate: a regime falters when the actions of one or several groups cast doubts on the viability of the rules regulating political interactions. It collapses once these rules cease to be effective. Two processes may contribute to this state of affairs. In one, open conflict renders institutional rules obsolete. These rules no longer have a grip on political relations. Agents stop referring to them as they assess options and their immediate future. Institutional collapse results from a confrontation devoid of any prospect for compromise.

Abdication is the second process. Those upholding the regime abandon the struggle and pave the way to its restructuring. August 1789 in France, March 1933 in Germany, July 1940 in France, June 1958 in France, November 1976 in Spain, November 1989 in East Germany – these few cases suffice to gauge the scale of the phenomenon in dictatorial regimes as well as in democratic power structures.

We cannot therefore analyze regime breakdowns solely as the consequence of coups. Breakdown can also take place through the renunciation of power and collective action. The preceding observations set out to explain this modality of breakdown, taking as their starting point commonsensical hypotheses, namely constraint, miscalculation, and ideological collusion. A critical examination of common sense underscores the need to account for variation in behavior in the face of constraint. In addition, a critical examination calls into question the assumption of homogenous individual dispositions. The key point is the following: political renunciation involves making a choice. We uncover its underlying logic when we analyze it as such.

This analytical framework brings into relief the significance of heteronomous choices and their cognitive underpinnings for our understanding of the dynamics of collective behavior. Heteronomy and uncertainty reveal that abdication cannot ex ante be taken for granted however daunting and incapacitating a decisional challenge proves to be. Moreover, this analytical framework highlights two types of alignment. Alignment is sequential when actors model their decisions on those who already have committed themselves to a behavioral stance. It rests on a process of expectation formation when actors strive to anticipate the behavior of their peers on the basis of informal exchange (“local knowledge”) or the expected repercussions of a public event (“tacit alignment”). Ultimately, theorizing regime breakdown implies theorizing processes of collective alignment38.

Notes

1

Patrick Kessel, La Nuit du 4 Août 1789, Paris, Arthaud, 1969; Jean-Pierre Hirsch, La Nuit du 4 août, Paris, Gallimard/Julliard, 1978; Timothy Tackett, Becoming a Revolutionary. The Deputies of the French National Assembly and the Emergence of a Revolutionary Culture (1789-1790), Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1996.

2

Jean-Antoine-Nicolas de Caritat Condorcet, Mémoires de Condorcet sur la révolution française: extraits de sa correspondance et de celles de ses amis, Paris, Ponthieu, vol. II, 1824, p. 60; quoted in Kessel, La Nuit du 4 Août 1789, Paris, Arthaud, 1969, p. 173.

3

François Furet, “Nuit du 4 août 1789”, in F. Furet, M. Ozouf (dir.), Dictionnaire critique de la révolution française, Paris, Flammarion, 1988, p. 126-132.

4

Quoted in Patrick Kessel, La Nuit du 4 Août 1789, Paris, Arthaud, 1969, p. 179.

5

Juan J. Linz, Alfred Stepan, Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation, Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996, p. 91-96. Josep Colomer, writing about the vote on November 18, 1976, during which members of the Cortes – the assembly of representatives designated by the government or elected by corporatist bodies – approved their own dissolution, describes it as a political “harakiri” (Josep M. Colomer, Game Theory and the Transition to Democracy, Aldershot, Edward Elgar, 1995, p. 58-59). Ignacio Sánchez-Cuenca evokes “an institutional suicide” (Ignacio Sánchez-Cuenca, Atado y mal atado: El suicidio institucional del franquismo y el surgimiento de la democracia, Madrid, Alianza, 2014).

6

“Most ruling parties fell without resistance: They abdicated, willingly gave up power, and melted away” (Vladimir Tismaneanu, Reinventing Politics: Eastern Europe from Stalin to Havel, New York, Free Press, 1992, p. XI).

7

Allister Sparks, Tomorrow is Another Country: The Inside Story of South Africa's Road to Change, New York, Hill and Wang, 1995, p. 180-195.

8

Ivan Ermakoff, Ruling Oneself Out: A Theory of Collective Abdications, Durham, Duke University Press, 2008, chapter 2.

9

René Rémond, Le Retour de De Gaulle, Paris, Complexe, 1987.

10

Karl Dietrich Bracher, “Stufen der Machtergreifung”, in K. Bracher, W. Sauer, G. Schulz (eds.), Die nationalsozialistische Machtergreifung. Studien zur Errichtung des totalitären Herrschaftssystems in Deutschland 1933-34, Cologne and Opladen, Westdeutscher Verlag, 1962, p. 159; Rudolf Morsey, Der Untergang des politischen Katholizismus. Die Zentrumspartei zwischen christlichem Selbstverständnis und “Nationaler Erhebung” 1932-33, Stuttgart, Belser Verlag, 1977, p. 144.

11

Otto Buchwitz, 50 Jahre Funktionär der deutschen Arbeiterbewegung, Berlin-Est, Dietz Verlag, 1950, p. 149; Josef Felder, “Mein Weg: Buchdrucker – Journalist – SPD Politiker”, p. 15-79 in Abgeordnete des Deutschen Bundestages. Aufzeichnungen und Erinnerungen, vol. 1, Boppard, Boldt, 1982, p. 37; Wilhelm Hoegner, Der schwierige Außenseiter. Erinnerungen eines Abgeordneten, Emigranten und Ministerpräsidenten, Munich, Isar Verlag, 1959, p. 129.

12

Ivan Ermakoff, Ruling Oneself Out: A Theory of Collective Abdications, Durham, Duke University Press, 2008, chapter 3, p. 90-91.

13

“Im Jahre 1933 wusste auch noch niemand, welche Richtung Hitler nach der Machtübernahme einschlagen würde, denn seine Regierungserklärung war gemässigt und voll beruhigender Zusicherungen nach Innen und Aussen. Niemand konnte zu diesem Zeitpunkt ahnen, welch einem Lügner und Betrüger einmaligen geschichtlichen Formats das Volk in die Hände gefallen war” (NL Farny, I-468, 001-1, Archiv der Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, Sankt Augustin). Unless otherwise noted, the translations are the author’s.

14

Der gerade Weg, p. 3: title of the editorial: “A Catholic votes in accordance with his principles” (“Der positive Katholik wählt grundsätzlich”). Der gerade Weg explicitly recognized that its readership was Catholic (Archiv der Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, Sankt Augustin, Fonds Scherer, I-046, 002-3).

15

John E. Finn, Constitutions in Crisis. Political Violence and the Rule of Law, New York and Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1991, p. 163.

16

“Man sucht ein neues Staatsrecht. Man formuliert einen neuen Begriff vom Staat, der sagt: Der Staat kann alles und darf alles; der einzelne ist nichts und bedeutet nichts. ... Das ist eine Lehre, die mit dem Naturrecht, mit unserer christlichen Auffassung in absolutem Gegensatz steht. ... Deshalb wollen wir von allem Anfang an gegen diesen Begriff des Staates und diese Übersteigerung der staatlichen Macht Front machen”. Kölnische Volkszeitung, February 15, 1933. The title of this transcript of a speech by Bolz is explicit: “What is at stake” (“Was auf dem Spiele steht”).

17

“Alles wird monopolisiert. ... Aber ... wir werden niemals dulden, daß man Deutschland parteipolitisch monopolisiert, und daß man alles diffamiert, was sich diesem sachlich wahrhaftig nicht gerechtfertigten Monopolisierungsanspruch widersetzt”. Kölnische Vokszeitung, March 3, 1933.

18

Kommission für Zeitgeschichte, Bonn. Fonds Dessauer FD 12, Nr. 7136.

19

Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, Sankt Augustin, Nachlaß Bormann, I-352, Mappe 9, “Streng vertraulich”, p. 1. Regarding verbal exchanges among deputies, see Ivan Ermakoff, Ruling Oneself Out: A Theory of Collective Abdications, Durham, Duke University Press, 2008, p. 99.

20

Ivan Ermakoff, Ruling Oneself Out: A Theory of Collective Abdications, Durham, Duke University Press, 2008, chapter 4, p. 93-94.

21

Vilfredo Pareto, The Rise and Fall of Elites: An Application of Theoretical Sociology, introduction by Hans L. Zetterberg, New Brunswick, Transaction, 2008.

22

“By 1989, party bureaucrats did not believe in their speech. And to shoot, one must believe in something. When those who hold the trigger have absolutely nothing to say, they have no force to pull it” (Adam Przeworski, Democracy and the Market: Political and Economic Reforms in Eastern Europe and Latin America, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1991, p. 6).

23

Rudolf Lill, “NS-Ideologie und katholische Kirche”, p. 151-172 in K. Gotto, K. Repgen (eds.), Die Katholiken und das Dritte Reich, Mainz, Matthias-Grünewald-Verlag, 1990, p. 138.

24

“Das Ermächtigungsgesetz sei das Ungeheuerlichste, was je von einem Parlamente gefordert worden war” (Rudolf Morsey (ed.), Die Protokolle der Reichstagsfraktion und des Fraktionsvorstandes der deutschen Zentrumspartei. 1926-1933, Mainz, Matthias-Grunewald-Verlag, 1969, p. 631).

25

“Entschluß ..., der zum Schwersten gehört, was ich in meinem Leben überstanden habe ...” (Letter to Brüning dated March 27, 1933; Kommission für Zeitgeschichte, Bonn, Nachlaß Dessauer FD 12 Nr. 6596-6597).

26

Ivan Ermakoff, Ruling Oneself Out: A Theory of Collective Abdications, Durham, Duke University Press, 2008, preface.

27

“Prälat Kaas [erklärte], daß niemand die Verantwortung für eine Einzelabstimmung übernehmen könne, diese Verantwortung sei zu schwer -- das Votum könne nur entpersönlicht sein, nur ein einheitliches Votum schaffe Entpersönlichung in der Annahme des Ermächtigungsgesetzes” (Tagebuchaufzeichnungen von Clara Siebert reproduce by Morsey (ed.), in Das‚ Ermächtigungsgesetz’ vom 24. März 1933. Quellen zur Geschichte und Interpretation des Gesetzes zur Behebung der Not von Volk und Reich’, Düsseldorf, Droste Verlag, 1992, p. 137).

28

Granovetter has formalized this process using the notion of individual thresholds: Mark Granovetter, “Threshold Models of Collective Behavior”, American Journal of Sociology, vol. 6, n° 83, 1978, p. 1420-1443.

29

For an analysis of the cognitive processes at play in these two scenarios, see Ivan Ermakoff, Ruling Oneself Out: A Theory of Collective Abdications, Durham, Duke University Press, 2008, chapter 6; “Motives and Alignment”, Social Science History, Special Section: Politics, Collective Uncertainty, and the Renunciation of Power, vol. 1, n° 34, 2010, p. 97-109.

30

Patrick Kessel, La Nuit du 4 Août 1789, Paris, Arthaud, 1969, p. 116.

31

Georges Lefebvre, Quatre-vingt-neuf, Paris, Éditions Sociales, 1970; John Markoff, The Abolition of Feudalism: Peasants, Lords, and Legislators in the French Revolution, University Park, Pennsylvania, The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996, p. 300-1, 336-7.

32

Jean-Pierre Hirsch, La Nuit du 4 août, Paris, Gallimard/Julliard, 1978, p. 145-146.

33

Le Bon's account of the night of August 4 draws on this interpretion. Gustave Le Bon, La Psychologie des foules, Paris, Félix Alcan, 1908; Sigmund Freud, Psychologie collective et analyse du moi, translation by S. Jankélévitch, Paris, Payot, 1921.

34

Herbert Blumer, “Collective Behavior”, in R. E. Park (ed.), An Outline of the Principles of Sociology, New York, Barnes, 1939, p. 222-4. Randall Collins offers a systematic analysis of the ecological parameters and implications of this sort of emotional dynamic (Randall Collins, “Social Movements and the Focus of Emotional Attention”, p. 27-44 in Passionate Politics: Emotions and Social Movements, edited by J. Goodwin, J. M. Jasper, F. Poletta, Chicago and London, The University of Chicago Press, 2001; Interaction Ritual Chains, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2004).

35

Émile Durkheim, Les Formes élémentaires de la vie religieuse, Paris, PUF, 1995, p. 211. For an analysis in terms of “emotional flux” which chimes with Durkheim's interpretation, see Randall Collins, “Social Movements and the Focus of Emotional Attention”, in J. Goodwin, J. M. Jasper, F. Poletta (eds.), Passionate Politics: Emotions and Social Movements, p. 27-44, Chicago and London, The University of Chicago Press, 2001, p. 41.

36

Charles Élie marquis de Ferrières, Mémoires, vol. 1, Paris, Baudouin, 1821, p. 189. Trophime-Gérard Lally-Tolendal was deputy of the “noble citizens of Paris” (A. Robert, E. Bourloton, G. Cougny (dir.), Dictionnaire des parlementaires français comprenant tous les membres des Assemblées françaises et tous les ministres français depuis le 1er mai 1789 jusqu’au 1er mai 1889, tome Troisième, Paris, Bourloton, 1891, p, 549).

37

Ivan Ermakoff, “The Structure of Contingency”, American Journal of Sociology, n° 121, 2015, p. 64-125, p. 97-99; “Cognition, Emotions and Collective Alignment: A Response to Collins”, American Journal of Sociology, n° 123, 2017, p. 284-291.

38

Ivan Ermakoff, Ruling Oneself Out: A Theory of Collective Abdications, Durham, Duke University Press, 2008, chapter 6; “Motives and Alignment”, Social Science History, Special Section: Politics, Collective Uncertainty, and the Renunciation of Power, vol. 1, n° 34, 2010, p. 97-109.

Bibliographie

Herbert Blumer, “Collective Behavior”, in R. E. Park (dir.), An Outline of the Principles of Sociology, New York, Barnes, 1939.

Karl Dietrich Bracher, “Stufen der Machtergreifung”, in K. Bracher, W. Sauer, G. Schulz (dir.), Die nationalsozialistische Machtergreifung. Studien zur Errichtung des totalitären Herrschaftssystems in Deutschland 1933-34, Cologne et Opladen, Westdeutscher Verlag, 1962.

Otto Buchwitz, 50 Jahre Funktionär der deutschen Arbeiterbewegung, Berlin-Est, Dietz Verlag, 1950.

Jean-Antoine-Nicolas de Caritat Condorcet, Mémoires de Condorcet sur la révolution française: extraits de sa correspondance et de celles de ses amis, Paris, Ponthieu, tome II, 1824.

Randall Collins, “Social Movements and the Focus of Emotional Attention”, in J. Goodwin, J.M. Jasper, F. Poletta (eds.), Passionate Politics: Emotions and Social Movements, Chicago et Londres, The University of Chicago Press, 2001, p. 27-44.

Randall Collins, Interaction Ritual Chains, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2004.

Josep M. Colomer, Game Theory and the Transition to Democracy, Aldershot, Edward Elgar, 1995.

Émile Durkheim, Les Formes élémentaires de la vie religieuse, Paris, PUF, 1995.

Ivan Ermakoff, Ruling Oneself Out: A Theory of Collective Abdications, Durham, Duke University Press, 2008.

Ivan Ermakoff, “Motives and Alignment”, Social Science History, Special Section: Politics, Collective Uncertainty, and the Renunciation of Power, vol. 1, n° 34, 2010, p. 97-109.

Ivan Ermakoff, “The Structure of Contingency”, American Journal of Sociology, n° 121, 2015, p. 64-125.

Ivan Ermakoff, “Cognition, Emotions and Collective Alignment: A Response to Collins”, American Journal of Sociology, n° 123, 2017, p. 284-291.

Josef Felder, “Mein Weg: Buchdrucker – Journalist – SPD Politiker”, in Abgeordnete des Deutschen Bundestages. Aufzeichnungen und Erinnerungen, vol. 1, Boppard, Boldt, 1982, p. 15-79.

Charles Élie marquis de Ferrières, Mémoires, vol. 1, Paris, Baudouin, 1821.

John E. Finn, Constitutions in Crisis. Political Violence and the Rule of Law, New York & Oxford, Oxford University Press, 1991.

Sigmund Freud, Psychologie collective et analyse du moi, traduction de S. Jankélévitch, Paris, Payot, 1921.

François Furet, “Nuit du 4 août 1789”, in F. Furet, M. Ozouf (dir.), Dictionnaire critique de la révolution française, Paris, Flammarion, 1988, p. 126-132.

Mark Granovetter, “Threshold Models of Collective Behavior”, American Journal of Sociology, vol. 6, n° 83, 1978, p. 1420-1443.

Jean-Pierre Hirsch, La Nuit du 4 août, Paris, Gallimard/Julliard, 1978.

Wilhelm Hoegner, Der schwierige Außenseiter. Erinnerungen eines Abgeordneten, Emigranten und Ministerpräsidenten, Munich, Isar Verlag, 1959.

Patrick Kessel, La Nuit du 4 Août 1789, Paris, Arthaud, 1969.

Gustave Le Bon, La Psychologie des foules, Paris, Félix Alcan, 1908.

Rudolf Lill, “NS-Ideologie und katholische Kirche”, in K. Gotto, K. Repgen (dir.), Die Katholiken und das Dritte Reich, Mainz, Matthias-Grünewald-Verlag, 1990, p. 151-172.

Juan J. Linz, Alfred Stepan, Problems of Democratic Transition and Consolidation, Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1996.

John Markoff, The Abolition of Feudalism: Peasants, Lords, and Legislators in the French Revolution, University Park, Pennsylvanie, The Pennsylvania State University Press, 1996.

Rudolf Morsey, Der Untergang des Politischen Katholizismus. Die Zentrumspartei zwischen christlichem Selbstverständnis und “Nationaler Erhebung” 1932-33, Stuttgart, Belser Verlag, 1977.

Rudolf Morsey (dir.), Die Protokolle der Reichstagsfraktion und des Fraktionsvorstandes der deutschen Zentrumspartei. 1926-1933, Mainz, Matthias-Grunewald-Verlag, 1969.

Rudolf Morsey (dir.), Das ,Ermächtigungsgesetz’ vom 24. März 1933. Quellen zur Geschichte und Interpretation des ‚Gesetzes zur Behebung der Not von Volk und Reich’, Düsseldorf, Droste Verlag, 1992.

Georges Lefebvre, Quatre-vingt-neuf, Paris, Éditions Sociales, 1970.

Vilfredo Pareto, The Rise and Fall of Elites: An Application of Theoretical Sociology, introduction de Hans L. Zetterberg, New Brunswick, Transaction, 2008.

René Rémond, Le Retour de De Gaulle, Paris, Complexe, 1987.

Adolphe Robert, Edgar Bourloton, Gaston Cougny (dir.), Dictionnaire des parlementaires français comprenant tous les membres des Assemblées françaises et tous les ministres français depuis le 1er mai 1789 jusqu’au 1er mai 1889, Paris, Bourloton, 1891.

Ignacio Sánchez-Cuenca, Atado y mal atado: El suicidio institucional del franquismo y el surgimiento de la democracia, Madrid, Alianza, 2014.

Alistair Sparks, Tomorrow is another country: the inside story of South Africa's road to change, New York, Hill and Wang, 1995.

Timothy Tackett, Becoming a Revolutionary. The Deputies of the French National Assembly and the Emergence of a Revolutionary Culture (1789-1790), Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1996.

Vladimir Tismaneanu, Reinventing Politics: Eastern Europe from Stalin to Havel, New York, Free Press, 1992.