Introduction

This article discusses the relationship between spiritual universalism and antiracism in Japan and India in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, in the context of transnational spiritual-moral movements and how such movements significantly influenced global antiracism in the early twentieth century. Antiracist internationalism based on the universal equality of nations developed in the wake of critiques of hierarchical views of race and civilization ranked according to material development. The history of this critical revision will be traced from the World’s Parliament of Religions held in Chicago in 1893, through the First Universal Races Congress held in London in 1911, to the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation (1922-1946) leading to the establishment of UNESCO (1946). It is my contention that spiritual universalism played an important role in this transition.

In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, both Japan and India attempted to reflect upon and re-define their national selves in relation to their culture and religion1. They were interested not only in demonstrating their cultural particularity as nations, but also in asserting the universal value of their culture and religion. This led to the formation of modern Buddhism, modern Hinduism (neo-Hinduism), and other religious movements across Japan and India that pursued and asserted the universality of spiritual values above and beyond mere institutions or beliefs. Japanese and Indian intellectuals were eager to participate in “the cosmopolitan thought zones” and contribute to the formation of a new global future in which their nations would take their rightful and respectable place2. From this perspective, modern history could be interpreted as “an interplay of multiple and competing universalisms”3.

Although the ideational basis of antiracism is often viewed as resting on the equality in rights associated with the European Enlightenment4 and secular rationality, I would like to argue that, in the late nineteenth to early twentieth century, spiritual universalisms were often the basis for recognizing and advocating equality across cultural, national, and imperial borders, in Japan, India and elsewhere. In other words, it was through spiritual universalisms that Japanese and Indian people sought to express their “vernacular cosmopolitanism”–cosmopolitanism based not on the universalism of abstract reason, but on the universalisms of affect and faith stemming from the knowledge of both the vernacular and the global5.

Universal spiritualisms in Japan and India in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries resonated with each other, as they were both linked to nationalism and the critique of Euro-American racism. They were also connected to other antiracist movements critiquing white Christian Enlightenment supremacy. However, after the Russo-Japanese war, Japanese nationalism and its assertion of pan-Asianism came to be associated with its own imperialism. In this process, racist theories arguing the equal status of Japanese and western civilization, as well as the former’s superiority over other Asian nations, were put forward to legitimize Japanese colonial rule. Meanwhile, in India, discourses and debates on universal spiritualism continued to play a role in efforts to bring about the equality of nations internationally, and to engender harmony and coexistence between the country’s different social groups (based on religion, caste, class), as can be seen in the movements inspired by Gandhi and Ambedkar. The spiritual basis of Indian nationalism has survived, though it often gets conflated with the idea of Hindu supremacy today.

This form of spiritual universalism seeking racial and ethnic equality gradually lost its political relevance after the Second World War. It is my contention that despite this setback, we cannot ignore the legacy of spiritual universalism, which significantly influenced global movements seeking human equality. As the foundation for human equality cannot be sought in the body, which is, phenotypically at least, too diverse, there was a search for humanity’s universal essence. Because Enlightenment philosophy, which posits secular rationality as the essence of humanity6, often also provided the basis for Euro-white supremacy, movements pursuing racial equality sought human essence in something beyond the body and rationality, which was identified as the spiritual.

Nationalism and Religion: Kinza Hirai’s Modern Buddhism

In the late nineteenth century, the movement for the abolition of unequal treaties7 came to be linked with modern Buddhist movements in Japan, and anticolonial nationalism came to be linked with the formation of modern Hinduism in India. These movements were attempts to construct a new global order, based on the equality of religions and nations, and against European colonialism. Spiritual and occult movements were important in mediating between the west and the east as well as between science and mysticism8. For example, the Theosophical Society (est. 1875, New York) functioned as a catalyst for connecting and inspiring various global movements, though it was not free of sectarian biases9.

These movements, which sought universalism at the level of spirituality beyond differences in race, were deeply connected to the cultural and political nationalisms of Asian countries such as Japan and India. In other words, the main concern of these nationalisms in the late nineteenth century was to win recognition for their equal status in terms of the value of their culture and religion. It was on the grounds of this culturally equal status that Japan and India sought political and legal justice, that is, equal political rights for their people. We may see this clearly in statements by Kinza Hirai (1859-1916) and Swami Vivekananda (1863-1902) to the World's Parliament of Religions held in Chicago in 1893.

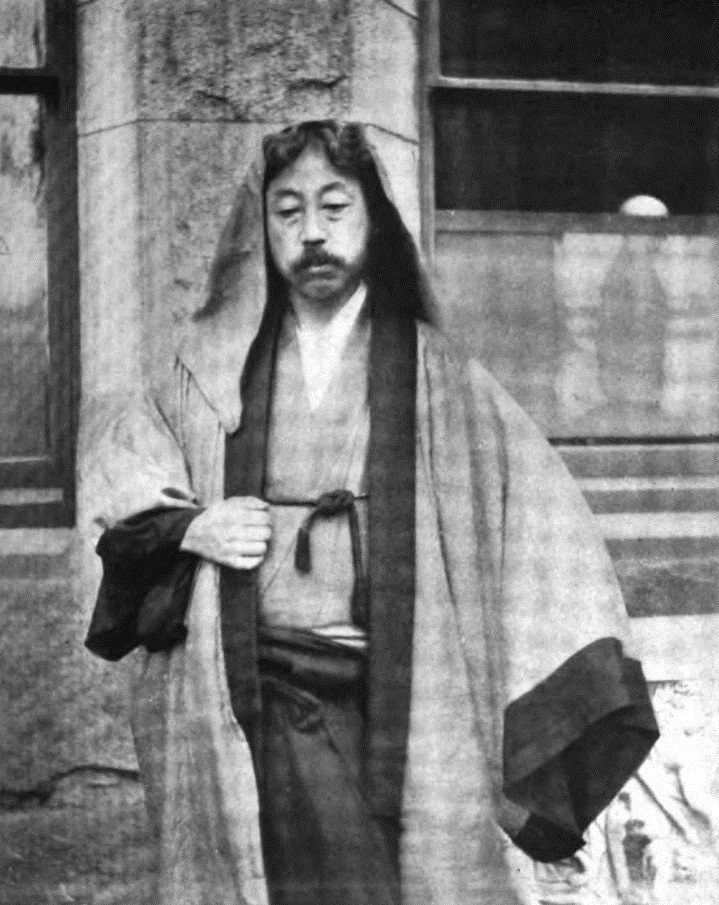

Among the Japanese delegates to the World's Parliament of Religions, Hirai is said to have been the most appreciated by the audience, though the star of the parliament was definitely Swami Vivekananda from India, who overshadowed all other participants. Let us first take a brief look at the life and work of Kinza Hirai.

Kinza Hirai

Walter R. Houghton (ed.), Neely’s History of the Parliament of Religions and Religious Congresses at the World’s Columbian Exposition, Chicago, F. T. Neely, 1893, p. 169.

Hirai was born in 1859 in Kyoto, eight years before the Meiji Restoration. His life took several turns, largely paralleling the meandering search for modern Japan’s self-identity. He received a modern education, including instruction in English, at a young age, but distaste for exams and other institutionalized systems led him to leave school. In 1881, Hirai established Kiyukai (Alarmist Society) and started a journal called Kiyushigen (Alarmist Journal), through which he criticized Christianity for disrupting Japan’s progress towards independence. In “Christianity: To be or not to be”, an article in this journal, hargued that the missionaries’ aim was “none other than to conquer people’s hearts through religion and to obtain our holy land by non-military means”10. He wished to resist colonialism by resisting Christianity and reviving Buddhism.

In January 1885, Hirai established the “Oriental Hall,” an English school based on Buddhism, expressing a stance against the Doshisha English School, based on Christianity, established in 1875 by Jo Niijima (Joseph Hardy Neesima). What was interesting about the Oriental Hall was that, as an English school based on Buddhism, it reflected the inflected combination of nationalism and internationalism in Hirai’s thought. The curriculum included Spencer’s The Study of Sociology, John Stewart Mill’s On Liberty, and Olcott’s A Buddhist Catechism. Masaharu Anesaki, the first religious studies professor at the University of Tokyo, studied at the Oriental Hall in his youth, and wrote of his fond memories of his education there11.

Hirai also built connections with the Theosophical Society which, at the time, was promoting Buddhist revivalism in colonial Ceylon and India. Hirai, together with Zenshiro Noguchi, invited Henry Steel Olcott and Anagarika Dharmapala to Japan in 1889. Olcott (1832-1907) founded the Theosophical Society with Helena Petrovna Blavatsky (1831-1891). Dharmapala (1864-1933) was a Ceylonese member of the Theosophical movement who was only in his twenties when he visited Japan. Later, in 1891, assisted by the British journalist and poet Sir Edwin Arnold, he went on to establish the Maha Bodhi Society. The purpose of the this society was to resuscitate Buddhism in India, and to restore the ancient Buddhist temple at Bodh Gaya. Dharmapala participated in the Chicago parliament, representing Ceylonese Buddhism, and winning popularity second only to Vivekananda12.

Olcott and Dharmapala stayed in Japan from February 9 to May 28, 1889, conducting a series of lectures and meetings seeking to kindle inter-sectional, unified Buddhist awareness in Japan. The initial welcome was enthusiastic, and Olcott looked back upon his Japan tour as a big success, but the subsequent reception among Buddhists in Japan was in fact decidedly mixed13. On his way back from the Chicago parliament, Dharmapala visited Japan again in 1893 to seek support for the Buddhist revival movement at Bodh Gaya. Shūkō Asahi, a monk at Tentokuji temple, responded by donating a Buddha statue said to have been made by Jōchō, a famous Buddhist sculptor, in the eleventh century14. Dharmapala’s Bodh Gaya revival movement continued, and for over a decade it pursued attempts to place and worship this statue of Buddha, donated from Japan, at the Bodh Gaya temple.

Kinza Hirai and Swami Vivekananda in Chicago

The World's Parliament of Religions was held in Chicago from September 11 to 27, 1893. The Buddhist delegates from Japan were Soen Shaku and Ashitsu Jitsuzen from the Rinzai sect, Horyu Toki from the Shingon sect, Banryu Yatsubuchi from the Jodoshinshu Honganji sect, as well as the lay men, Zenshiro Noguchi and Yozo Nomura as interpreters, along with Kinza Hirai. The Japanese delegates also included Reiichi Shibata, representing Shintoism, and Hiromichi Ozaki from Doshisha and Nobuta Kishimoto, then studying at Harvard, representing Christianity.

The Japanese delegation representing Buddhism. In front (from left to right): Toki Horyu, Yatsubuchi Banryu, Shaku Soen, and Ashitsu Jitsuzen.

At back (from left to right): Nomura Yozo and Noguchi Zenshiro.

Walter R. Houghton (ed.), Neely’s History of the Parliament of Religions and Religious Congresses at the World's Columbian Exposition, Chicago, F. T. Neely, 1893, p. 37.

At the World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, of which the Parliament of Religions was a part, Kakuzō Okakura (1862-1913) and Ernest Francisco Fenollosa (1853-1908), who together had founded the Tokyo School of Fine Arts in 1889, were largely responsible for the interior decoration of the Hōōden or Phoenix Pavilion where Japanese architecture and arts were displayed15. Hirai and Fenollosa later established a friendship based on universalist ideas on spiritual and aesthetic values16.

Hirai gave a lecture titled “The Real Position of Japan toward Christianity” on September 13, 1893. He pointed out that Christianity was unpopular in Japan due to its hypocritical attitude and links to imperialism. He explained the issue of the unequal treaties between Japan and the US, criticizing the underlying Christian morality. He said that while the people of Christendom insisted on human rights and human ethics, he did not “understand why the Christian lands have ignored the rights and advantages of forty million souls of Japan for forty years since the stipulation of the treaty”17. Hirai argued that this unequal treatment was drawn up with the excuses that Japan was “not yet civilized” and the Japanese were “idolaters and heathen”18. He thus questioned the presupposed equation of Christianity and civilization. In contrast to this self-righteous attitude of the Christians, he referred as follows to the open and synthetic character of Japanese religion:

“Be they heathen, pagan, or something else, it is a fact that from the beginning of our history, Japan has received all teachings with open mind; and also that the instructions which came from outside have commingled with the native religion with entire harmony …; as is seen by the popular ode:

Wake noburu

Fumoto no michi wa

Ooke redo,

Onaji takane no

Tsuki wo mini kana,”

which translated means, “Though there are many roads at the foot of the mountain, yet, if the top is reached, the same moon is seen”19.

He further claimed: “In reality Synthetic religion, or Entitism, is the Japanese specialty, and I will not hesitate to call it Japanism”20. In conclusion, Hirai quoted the Declaration of Independence: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal,” and then said that the citizens of “this glorious free United States […] may somewhat our position, and as you asked for justice from your mother country, we, too, ask justice from these foreign powers.” Lastly he said, “We, the forty million souls of Japan, standing firmly and persistently upon the basis of international justice, await still further manifestations as to the morality of Christianity”21.

His lecture was much appreciated by the audience. It was reported as follows in the Chicago Herald of September 14, 1893:

“Loud applause followed many of his declarations, and a thousand cries of ‘Shame’ were heard when he pointed to the wrongs which his countrymen had suffered through the practices of false Christianity. When he had finished, Dr. Barrows (a liberal Christian pastor of the First Presbyterian Church of Chicago, President of the Parliament) grasped his hand, and the Rev. Jenkin Lloyd-Jones (Unitarian in Chicago, Secretary of the Parliament) threw his arm around his neck, while the audience cheered vociferously and waved hats and handkerchiefs in the excess of enthusiasm22.”

Hirai gave his second talk, titled “Synthetic Religion,” on September 26. He argued that “Religion is a priori belief in an unknown entity”, and, if we understood this essence of religion, “(a)ll the religions in the world are synthetized into one religion or ‘Entitism’.” He said that such “Synthetic Religion” was indeed the inherent spirit in Japan. He talked of his vision of unity of all religions using phrases reminiscent of the Rinzai sect of Buddhism to which he belonged at the time. He said, “Stop your debate about the difference of religion. Kill Gautama…. Do not mind Christ…. Tear up the Bible”23. Here, he was talking of the universal truth as the final goal beyond all religious fetish. He even stopped promoting Buddhism and treated all religions as equal. Here we see an expression of modern spiritual universalism, which resonated with the views of Swami Vivekananda and Kakuzō Okakura24.

Hirai spoke in the concluding session as follows. “We cannot but admire the tolerant forbearance and compassion of the people of the civilized West. You are the pioneers in human history. You have achieved an assembly of the world's religions, and we believe your next step will be towards the ideal goal of this Parliament, the realization of international justice”25. This comment may be interpreted as a demand that the “civilized West” prove its worth via its attitudes to other nations.

It is noteworthy that Hirai, by asserting the universalist ethics that pervades all true religions, in fact challenges the very evolutionary framework of the cultural superiority of the west and Christianity presupposed by the organizer of the parliament. Instead of attempting to demonstrate that Buddhism or Japanese religion are as advanced as Christian culture, Hirai speaks of the open and synthetic character of Japanese religion as its virtue, thus denying the hierarchy of religions. Rather than appealing to his audience for universal justice and truth as rooted in Christian morality, he in fact overturns the western evolutionary framework, instead asking Christians whether they share the same universal value of justice and truth that exists in all true religions.

It should be noted that Hirai’s position differed from that of the Buddhist delegates and of the Japanese government. The Buddhist delegates viewed the parliament as an opportunity to propagate Japanese Buddhism26. In this, they were acting out of religious rivalry toward Christianity and in tacit conformity with the comparative framework offered by the parliament’s organizer27. The concern of the Japanese government, on the other hand, was to prove that Japan deserved equal status with other European nations in the hierarchy of development, thus conforming to the western scale of values28. Gozo Tateno, the Japanese Plenipotentiary Minister at Washington DC, stated that “it is just that they (the Japanese people) welcome the Columbian Exposition as one means of proving that they have attained a position worthy of the respect and confidence of other nations”29.

Although Hirai also demanded revision of the unequal treaty, and shared certain political concerns with the Japanese government30, the kind of equality he saw was based on the equality of truth that existed in all religions. Thus, while the Buddhist delegates were concerned with comparative religious values, and the Japanese government with increasing the country’s status in the hierarchy of nations, Hirai’s utmost concern was to assert justice and truth based on universal spiritual value31. These differences are important as they are indicative of the ambivalent aspects of later Japanese pan-Asianism: solidarity-oriented Asian universalism and material evolutionism placing Japan as the leader of Asia. Hirai’s stance based on spiritual universalism at the parliament in fact resonated not so much with other Japanese delegates as with Swami Vivekananda and Dharmapala32.

Swami Vivekananda became by far the most popular of the speakers at the Parliament of Religions. Echoing Hirai’s “synthetic religion,” Vivekananda said that “we accept all religions to be true”, quoting a Hindu sacred text: “As the different streams having their sources in different places all mingle their water in the sea, so, O Lord, the different paths which men take through different tendencies, various though they appear, crooked or straight, all lead to thee”33. This poetic image of different streams reaching the same ocean resonates with the Japanese poem Hirai quoted about many roads reaching the same mountain top. Vivekananda argued that different religions coexisted in Hinduism, thus presenting Hinduism as an open and tolerant religion, again reminiscent of Japanese syncretism put forward by Hirai. Vivekananda ultimately went beyond Hinduism and talked about a “universal religion.” He said:

“The Hindu might have failed to carry out all his plans, but if there is to be a universal religion, [… it] would be a religion which would have no place for persecution or intolerance in its polity, and would recognize a divinity in every man or woman, and whose whole scope, whose whole force would be centered in aiding humanity realize its human nature”34.

On the platform of the World's Parliament of Religions (left to right), Virchand Gandhi, Anagarika Dharmapala, Swami Vivekananda, G. Bonet Maury and Nikola Tesla.

Here we note a modern spiritual universalism seeing divinity equally in all humans, as their true nature, and calling for universal justice beyond any “persecution or intolerance”35.

Hirai and Vivekananda are often viewed as having promoted Buddhism and Hinduism respectively in connection with their cultural nationalism. This view is not totally wrong, but we should also note that their perspectives went beyond nationalist assertions, promoting the universal value of humanity based on spirituality. Such perspectives make the boundary between different religions, races, and nations porous and blurred, thus enabling trans-border communication. The universality of the divine spirit in all humanity was the common ideal propagated by both Hirai and Vivekananda, and which was to underpin the agenda of interreligious understanding and international justice beyond racism and colonialism36.

Cultural exchange between Japan and India: Asian Universalism

The cultural and spiritual aspirations of Japan and India combined with the search for a better world beyond racism and colonialism echoed with each other, and led to fruitful interactions between Kakuzō Okakura, Swami Vivekananda, and Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941), among others37.

After his grand success at the Chicago parliament, Vivekananda visited the US, then Europe, before returning to India via Ceylon in January 1897. On May 1, 1897 he established the Ramakrishna Mission based on the principle of Advaita (non-duality), the essence of Vedanta, which sees the divine essence in all things.

After his journey to Ceylon, Vivekananda gave a critical speech on Buddhism as part of a series of lectures in Madras38. He talked of “Buddhistic degradation” that gave birth to degraded rituals and writings in India, and said, “The whole work of India is a reconquest of this Buddhistic degradation by the Vedanta”, which was an ongoing process39. When questioned by American friends, who were surprised by Vivekananda’s criticism of Buddhism, Vivekananda explained that though he loved Dharmapala “it would be entirely wrong for him to go into fits over things Indian” and that he was convinced that “what they call modern Hinduism with all its ugliness is only stranded Buddhism”40. Vivekananda further mentioned that he was disappointed with the Buddhists in Ceylon, and “we will only be too glad if the Ceylonese carry off the remnant of this religion with its hideous idols and licentious rites”41. Later, however, Vivekananda again changed his position regarding Buddhism, saying “a total revolution has occurred in my mind about the relation of Buddhism and Neo-Hinduism”42. This revolution followed from his association with Okakura and their trip together to Bodh Gaya in 1902, just five months before his demise.

Okakura came to know about Swami Vivekananda through Miss Josephine MacLeod43 (1858–1949), an American friend and devotee of Vivekananda. Okakura, together with Miss MacLeod and Tokuno Oda, a Buddhist Abbot of the Shinshu Otani Sect, went to Calcutta in 1902 to invite Vivekananda to Japan for an intended “Asian Parliament of Religions” in Kyoto, which did not materialize44. Okakura and his party arrived in Calcutta on January 6 and immediately went to Belur Math to see Vivekananda. Okakura and Vivekananda developed a congenial relationship as of their first meeting45. On January 27, Vivekananda took Okakura and his party for a trip to Bodh Gaya. They arrived in Gaya on the 28th, and stayed there till February 4. During this trip Vivekananda and his guests stayed at the Hindu mahant’s house and observed the situation. After this, Okakura visited Bodh Gaya twice more, in April and probably in August, in his attempt to acquire a plot of land to build a Buddhist temple there. Vivekananda’s deteriorating health did not permit him to accompany Okakura46.

Vivekananda had talked about the need to re-connect Hinduism and Buddhism in the Chicago parliament. He said that “Shâkya Muni came not to destroy, but he was the fulfilment, the logical conclusion, the logical development of the religion of the Hindus”, and as Buddhism perished in India, Brahminism lost “that reforming zeal, that wonderful sympathy and charity for everybody, that wonderful heaven which Buddhism had brought to the masses and which had rendered Indian society so great”47. He further said:

“Hinduism cannot live without Buddhism, nor Buddhism without Hinduism. Then realise what the separation has shown to us, that the Buddhists cannot stand without the brain and philosophy of the Brahmins, nor the Brahmin without the heart of the Buddhist. This separation between the Buddhists and the Brahmins is the cause of the downfall of India. … Let us then join the wonderful intellect of the Brahmins with the heart, the noble soul, the wonderful humanising power of the Great Master (Buddha)”48.

Such a favorable view of Buddhism was lost after he visited Ceylon in January1897, seen above. In February of that year, Vivekananda even went so far as to say in an interview: “All along, in the history of the Hindu race, there never was any attempt at destruction, only construction. One sect wanted to destroy, and they were thrown out of India: They were the Buddhists”49. Vivekananda, however, held a positive view of Japanese Buddhism from his experience in Japan. He said “Japanese Buddhism is entirely different from what you see in Ceylon. It is the same as Vedanta. It is positive and theistic Buddhism, not the negative atheistic Buddhism of Ceylon”50.

After visiting Bodh Gaya with Okakura and Oda, Vivekananda seems to have acquired a fresh perspective – “a total revolution” – which reconciled his idea that Buddhism needed reconnecting with Hinduism and his experiential understanding of the difference between Ceylonese and Japanese Buddhism. After his visit to Bodh Gaya, Vivekananda said “the Mahâyâna school is even Advaitistic. […] I hold the Mahayana to be the older of the two schools of Buddhism”51. He also points out that “Shiva-worship, in various forms, antedated the Buddhists” at present Buddhist sites52. Further, he says “it seems that the Tibetans and the other Northern Buddhists have been coming here to worship Shiva all along. […] The Buddhists are not considered non-Hindus in any of our great temples”, probably implying historical continuity between Shiva worship and Mahayana Buddhism53.

It was Southern or Theravada Buddhism–which developed after Mahayana Buddhism–which, as Vivekananda saw it, had been a destructive and degrading influence on India, and had to be deported. “The lines of work” based on the “total revolution” in Vivekananda’s mind “about the relation of Buddhism and Neo-Hinduism” (which he was planning to leave behind for his disciples to complete), was most probably to reconnect Mahayana Buddhism, which upheld the spirit of Vedanta and “the wonderful sympathy and charity for everybody”, with popular Hinduism as represented by Shiva-worship, so as to construct a neo-Hinduism that would uphold the Vedantic spirit of knowledge, universal love of humanity, and popular support of the Indian nation54. This was a vision that would connect Vedanta with popular Hinduism, and Hindu India with Mahayana Buddhist Asia. Vivekananda’s vision of spiritual universalism was widening deeper into Indian society and wider towards east Asia till his demise in July 1902.

Okakura stayed in India for nine months, and, in addition to his friendship with Vivekananda, associated closely with Rabindranath Tagore and his relatives. This led to rich cultural interactions between Japanese and Indian intellectuals and artists. “Asian cosmopolitanism” emerged, asserting an alternative universalism based on spirituality and aesthetics. Asian cosmopolitanism acknowledged the common spiritual value of Asia, contrasting it to the instrumental material culture of the west. It was accompanied by severe criticisms of western imperialism and racism.

Okakura’s book on Asian artistic and cultural history, The Ideals of the East with Special Reference to the Art of Japan (1903), eloquently proclaims Asian cosmopolitanism:

“Asia is One. The Himalayas divide, only to accentuate, two mighty civilizations, the Chinese with its communism of Confucius, and the Indian with its individualism of the Vedas. But not even the snowy barriers can interrupt for one moment that broad expanse of love for the Ultimate and Universal, which is the common thought-inheritance of every Asiatic race, enabling them to produce all the great religions of the world, and distinguishing them from those maritime peoples of the Mediterranean and the Baltic, who love to dwell on the Particular, and to search out the means, not the end, of life”55.

This book was edited and introduced by Sister Nivedita (Margaret Elizabeth Noble, 1867- 1911) who, thanks to an introduction from Miss MacLeod, met Okakura at Tagore’s house. Sister Nivedita had spent her childhood and early youth in Ireland. She was a disciple of Swami Vivekananda and dedicated her life to the education of Indian women and the cause of Indian nationalism. Here, we see how Asian cosmopolitanism based on spirituality managed to connect Japanese nationalism and Indian nationalism across racial borders.

Kakuzō Okakura

In The Awakening of Japan (1904), Okakura’s critique of western racism and imperialism becomes more explicit. Here he argued that “the glory of the West is the humiliation of Asia”56. He criticized the “White Disaster” of western imperialism, as a counternarrative to the “Yellow Peril”57. Here, we see an example of “race as resistance”, where a racial category is used as “a discursive strategy to expose existing (or contemporary) racial discrimination”58.

Though Okakura’s ideals were based on Asian spirituality and beauty, his words were later quoted and exploited by Japanese imperial expansionists. Setting apart Okakura’s intentions, his discourse was double-edged, as it could support both transnational antiracism as well as imperialism in other Asian nations.

In 1929 Rabindranath Tagore talked of his fond memory of Okakura as follows:

“Some years ago I had the real meeting with Japan when a great original mind, from these shores came in our midst. […] The voice of the East came from him to our young men. That was a significant fact, a memorable one in my own life. And he asked them to make it their mission in life to give some great expression of the human spirit worthy of the East. It is the responsibility which every nation has, to reveal itself before the world”59.

Here we note Tagore’s positive evaluation of Okakura’s pan-Asian pursuit of human spirituality, which was totally different from the kind of imperialist-nationalism that sought self-expansion of power and wealth.

Such was late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Asian cosmopolitanism across Japan and India, based on spiritual universalism. It was critical of western racism and imperialism, calling on Asian nations to rise and express their spirit to prove their worth before the world. However, this kind of pan-Asian universalism was to play only a secondary role under–or worse, function as an ideological cover-up for–Japan’s increasingly imperialist pursuits after the Russo-Japanese war (1905-1906). The political intensification of nationalisms in Japan and India thereafter accompanied their divergent developments, reflecting their different political standings.

The parting of ways

Japan’s victory in the war with Russia further spurred anticolonial nationalist movements in Asia, stimulating pan-Asianist and pan-Islamist movements60. However, the rise of nationalisms in Asian countries also led to divergences, as differences in positionality surfaced.

As Prasenjit Duara, following Bunzo Hashikawa, aptly points out, pan-Asianism in Japan contained two aspects: “the solidarity-oriented, non-dominating conception of Japan’s role in reviving Asia, as well as the conception of Japan as … the harmonizing or synthesizing leader”61. In other words, one facet of Japanese pan-Asianism had some resonance with spiritual universalism, and thus solidarity with Asian people on equal terms, while another facet was associated with insisting on equal status with the west in the evolutionary hierarchy, hence placing Japan above other Asian nations. After the Russo-Japanese war, however, Japanese pan-Asianism increasingly came to emphasize the latter aspect, though without losing the former aspect: It placed Japan on a par with the west in the social Darwinist frame of evolution, while criticizing western imperialism, and cognizing cultural relationships with other Asian nations. Japan increasingly presented itself as the only nation capable of synthesizing European material development and Asian spiritual values. Here the meaning of Asian spirituality shifted from enhancing creative diversity based on the universal truth to valorizing the spiritual-cultural ethos that enabled “civilizational” development in terms of wealth and power.

The ambivalence and transformation of the Japanese attitude to Asia became clear when Japan propounded the racial equality proposal at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference while also demanding recognition for Japan’s “special interests” in the east in accordance with the so-called Asian Monroe Doctrine62. On February 13 Japan proposed an amendment to Article 21 (the religious freedom article) in the Covenant of the League of Nations:

“The equality of nations being a basic principle of the League of Nations, the High Contracting Parties agree to accord as soon as possible to all alien nationals of states, members of the League, equal and just treatment in every respect making no distinction, either in law or in fact, on account of their race or nationality.”

However, the majority was in favor of eliminating Article 21 altogether63. Japan then made a second proposal, on April 11, in the form of an insertion to the preamble of the Covenant: “… by the endorsement of principle of equality of nations and just treatment of their nationals [….]”64. Although this proposal gained a majority vote of eleven out of seventeen in the League of Nations Commission65, Woodrow Wilson, as chairman, imposed a unanimity ruling, to which Japan and France immediately objected. However, Wilson claimed that the resolution could not be considered adopted unless it was unanimous, given the manifest strong opposition66. In parallel to the racial equality negotiations, Japan negotiated on her claims to the former German colonies and associated rights to the Shantung Peninsula in China, as well as to the Pacific islands north of the equator67. On 30 April, Shantung was settled in Japan’s favor.

The racial equality proposal received popular supported in Japan. The movement for racial equality was originally led by the Association of National Diplomatic Alliance (Kokumin gaikō dōmei-kai) established in December 1914 by Ryōhei Uchida and Yasunosuke Tanabe, who promoted the pan-Asianist cause. Then the “League to Abolish Racial Discrimination” (Jinshu sabetsu teppai dōmei) held its first meeting on February 5, 1919, attended by some three hundred participants, including representatives from three political parties–Seiyukai, Kenseikai and Kokuminto–and twenty-four other public associations68. One of the key organizers was Mitsuru Tōyoma, the leader of the Genyōsha (Dark Ocean Association), a very influential pan-Asianist group.

Although Shimazu is indeed correct in stating that “the principle of racial equality, as we conceive of it today in the universality sense, was not even the issue at stake during the racial equality negotiations”69, this does not mean that there was no element of the universalist ideal in the popular support for racial equality. While it is true that the racial equality proposal in Japanese diplomacy was mostly related to Japan’s aspiration, as a non-white nation, to secure “great power status” equal to the western great powers70, the pan-Asianist zeal and ideology to support the racial equality proposal cannot be dismissed merely as disguised imperialism. Many pan-Asianists certainly sought egalitarian solidarity with Asian people, while also being entangled with the imperialist agenda, and support for the racial equality proposal shared this double-edged character. Just as “(p)an-Asianism in Japan both fed and resisted the nascent imperialism of that nation”71, the racial equality proposal also had the dual aspect of being both embedded in and going beyond Japanese imperialism-nationalism.

Was Japanese pan-Asianism then a kind of spiritual universalism? I would, in the final analysis, say no. Pan-Asianists like Mitsuru Tōyoma and Ryōhei Uchida did see an underlying unity among Asian societies, including, like Okakura, spiritual values, so we may note a definite resonance here. But the major difference was that Japanese pan-Asianists generally affirmed the use of violence–that is, the denial of “others”–for achieving their end. Whereas Okakura valued peace and endeavored to spread Asian spirituality as a universal value, including to the west, Japanese pan-Asianists saw violent confrontation against the west as inevitable. The idea of the inevitability and necessity of war between Asia and the west was later proposed most famously by the pan-Asianist thinker Shūmei Ōkawa (1886–1957), and the army officer Kanji Ishiwara (1889-1949) in Manchuria. In so far as pan-Asianists saw violence as necessary to achieve world peace, it cannot be called spiritual in its fullest sense, nor fully universalist, as opponents had to be contained or destroyed by force rather than convinced by the power of the universal truth.

As Japan increasingly headed towards imperial expansion in Asia, Tagore, a bosom friend of Okakura, criticized Japanese nationalism in his lectures at the Tokyo Imperial University and Keio University in 1916. He urged Japan not to be “a mere reproduction of the West” but to “apply your Eastern mind, your spiritual strength, your love of simplicity, your recognition of social obligation, in order to cut out a new path for this great unwieldy car of progress”72. Also, writing in the US in the same year, he stated:

“Our real problem in India is not political. It is social. This is a condition not only prevailing in India, but among all nations”73.

He pointed out:

“This problem of race unity which we have been trying to solve for so many years has likewise to be faced by you here in America. […] You have used violent methods to keep aloof from other races, but until you have solved the question here in America, you have no right to question India”74.

Tagore saw the need for social reform in all nations, and criticized the violent method by which racial hierarchy was maintained both inside a nation and between nations. He said:

“I am not against one nation in particular, but against the general idea of all nations. What is the Nation? It is the aspect of a whole people as an organized power. The organization incessantly keeps up the insistence of the population on becoming strong and efficient”75.

He proclaimed: “Nationalism is a great menace”76. Tagore’s view had a cosmopolitan and universalist flavor which went beyond the political nationalism of gaining power and competence.

Rabindranath Tagore and Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi.

In India, Annie Besant, who succeeded Madame Blavatsky as the president of the Theosophical Society in 1907, became involved in the nationalist movement, joining the Indian National Congress. During World War I, she and Bal Gangadhar Tilak launched the Home Rule League to campaign for democracy in India, and for dominion status within the British empire. This led to Besant’s election as president of the India National Congress in late 1917. Sister Nivedita, a disciple of Vivekananda and Okakura’s editor, also played an important role in the nationalist movement. Nivedita supported Besant and young Bengali revolutionaries, including Aurobindo Ghosh, one of the major contributors to the early nationalist movement. Ghosh later became Sri Aurobindo, a well-known saint whose organization was run by The Mother, (Mirra Alfassa, 1878-1973), a French lady who had stayed in Japan for four years and shared a house with Shūmei Ōkawa for a year (1919-1920) along with her husband Paul Richard (1874-1967)77. The position of Besant and Nivedita rested on the criticism of western oppression of Asia, and was associated with a plethora of nationalisms that varied between spiritual and political inclinations as well as peaceful and violent methods.

M.K. Gandhi (1869-1948) returned to India from South Africa in 1915 and assumed leadership of Congress in 1920. For Gandhi, religious inspiration and the spiritual search remained important throughout his “experiments with truth”78. It was Gandhi who firmly established the principle of “non-violence”–affirmation rather than denial of “others’–as the method of the nationalist movement. On this note, we may detect a definite divergence as of the 1920s between Japanese and Indian nationalisms: Japan shifted towards violent confrontation with the west, while India moved towards non-violent universalism.

According to Gandhi, violence occurs when self-interest is imposed on others. For Gandhi, independence, or swaraj, was equated to self-control, through which the self identifies with the affirmation of diverse manifestations of the universal truth. B. R. Ambedkar (1891-1956), a leader of the non-violent liberation movement of the dalits, the principal architect of the Constitution of India, and the first law minister of India, converted to Buddhism in 1956, two months before his death. As Gauri Viswanathan points out, his “conversion was less a rejection of political solutions than a rewriting of religious and cultural change into a form of political intervention”79.

It would be appropriate to understand Ambedkar’s conversion to Buddhism as a way of combining rational criticism and ontological (religio-ethical) commitment. Ambedkar says: “Religion, it is said, is personal. […] Contrary to this, Dhamma is social. Dhamma is righteousness, which means right relations between man and man in all spheres of life”80. After criticizing and deconstructing the existing caste order, Ambedkar required an ethical basis upon which to create a new social order. Buddhist dhamma was his answer. Gandhi and Ambedkar represent, in different ways, modern non-violent attempts to combine the spiritual search with socio-political movements seeking ethical relations beyond racist–including casteist–oppressions.

Spiritual universalism and internationalism

The potential of spiritual universalism in relation to antiracism was also spotted in early twentieth century Europe. It was Felix Adler (1851-1933) who first proposed an international congress on race at the International Union of Ethical Societies at Eisenach in 190681. Gustav Spiller (1864-1940) and Adler organized the first International Moral Education Congress at the University of London in September 1908, where they further promoted the idea of the Universal Races Congress (URC). The URC took place in London in 1911, with Adler as its chairman and Spiller the secretary of its General Committee.

What were the ideas behind these movements? Adler, a German American professor of political and social ethics, is known as the founder of ethical societies such as the New York Society for Ethical Culture (1877-). Though Adler was influenced by nineteenth-century secular moral traditions, especially Kantian universalism, in his later writings he went on to critique Kant. Instead of regarding the individual as an isolated being, as Kant does, Adler tells us to look at our “relation to others” in terms of “intrinsic connection”, and says that an individual has “worth only as an organic member of a spiritual whole”82. According to Adler, the essence of humanity, the grounds of our intrinsic connection, lies in our spiritual nature. Adler suggests “spiritual” instead of “rational” as the term “to designate that nature within us which operates in science and art and achieves its highest manifestation in producing the ethical ideal”83. For Adler, it was the common spiritual nature of human beings that was to underpin universal ethics.

Influenced by Adler in the US, Stanton George Coit (1857–1944) started ethical movements in the UK and founded the Union of Ethical Societies in 1896, later the Ethical Union, then the British Humanist Association, and now known as Humanists UK84. Coit employed Spiller as a lecturer for the ethical movement in 1901, and as secretary of the International Union of Ethical Societies in 1904. Spiller’s life’s work was to develop an “evolutionary psychology of human beings as ‘specio-psychic’, that is, developing by group assimilation of ‘the substance of the expressed thoughts of their whole species’.85”

Regarding the purpose of the URC, Spiller simply stated: “To discuss, in the light of modern knowledge and modern conscience, the general relations subsisting between the peoples of the West and those of the East, between so-called white and so-called coloured people, with a view to encouraging between them a fuller understanding, the most friendly feelings, and a heartier cooperation”86. Simplistic and idealistic it may indeed sound; however, it would be off the mark to say, as Rich does, that, “Its ethos was […] still one of nineteenth-century liberalism”87. Adler and Spiller endeavored to go beyond secular, scientific rationality, which were conjoined with nineteenth-century liberalism, and to establish a new ethics based on the universality of human spiritual nature88.

The First Universal Races Congress seated outside the entrance to the Imperial Institute, London.

The first URC, held over the course of four days of July 1911, attracted more than 2,100 people from fifty different countries89. The tone of the congress was characterized by progressivism based on ethical universalism and internationalism, with a commingling of scientific and moral discourses. Spiller later wrote as a coda that the congress confirmed “the substantial equality in innate capacity of the various races of mankind”90.

Among the papers circulated before the congress was one by Adler titled “The fundamental principle of inter-racial ethics and some practical applications of it”, in which he discussed humanity as a “corpus organicum spirituale” that would be promoted by the “reciprocity of cultural influence”91. Among others, Sister Nivedita (Miss Margaret Noble) discussed “The present position of woman”; Professor Franz Boas, often referred to as father of American Anthropology, the “Instability of human types”; and W. E. B. DuBois, an American scholar, civil rights activist, and pan-Africanist, presented a paper on “The negro race in the United States of America”92.

Attendees included Mrs. Annie Besant. Besant severely criticized the treatment accorded to Indians, not only in British India but also in Southern Africa93. Amongst the Congress’s Honorable General Committee members were Emile Durkheim, M.K. Gandhi, and Harumasa Anesaki. Anesaki had been one of Hirai’s students at Oriental Hall, and the first professor of Religious Studies at the University of Tokyo. Inspired by the Chicago parliament, Anesaki organized the Shūkyōka Kondankai (the Religionists’ Meeting, est. 1896) in Tokyo for promoting interreligious understanding. He was also active in the Kiitsu Kyokai (the Association Concordia, 1912-1942) which strove for "concord and cooperation between classes, nations, races, and religions”94.

It is important to note that there was a global confluence of regionally diverse and ideationally heterogeneous quests for alternative universalisms beyond the materialist and evolutionist idea of civilization. These included antiracist movements, anticolonial nationalisms, moral and spiritual movements, and academic and educational pursuits for alternative ideas and societies.

Meanwhile, the executive committee of the International Moral Education Congress proposed an international Bureau of Moral Education in 1910, and the International Moral Education Bureau was established at The Hague in 1921. In 1925, the International Bureau of Education (IBE), promoted by leading new educationists such as Pierre Bovet, Edouard Claparède, and Adolphe Ferrière, was established in Geneva. Behind the new education movement was the New Education Fellowship (NEF) established in 1921 by Beatrice Ensor (1885–1974), a theosophical educationist95. The origin of the NEF can be traced to the Theosophical Fraternity in Education, whose “keynote was faith in human nature and the spiritual powers latent in every child”96. The NEF was instrumental in connecting spiritually inspired educationists with major figures in psychology and education, such as Carl Gustav Jung, Jean Piaget, and John Dewey97. The IBE worked closely with the International Committee on Intellectual Cooperation (ICIC, 1922-1946), whose members included such prominent figures as Henri Bergson, Albert Einstein, Marie Curie, Rabindranath Tagore, and Inazō Nitobe. It also worked with the Paris-based International Institute of Intellectual Cooperation (IIIC, 1924-1946). The ICIC and IIIC later developed into UNESCO.

Thus, we note that the lineage of transnational spiritual universalism played an important role in nurturing internationalist activities based on the equality of all races and religions, leading eventually to the formation of UNESCO. Although Amrith and Sluga discuss the role of competing universalisms in the origin of the UN, including the role of anticolonial nationalism in the delegitimization of racism by UNESCO, their work does not take into account the genealogy of transnational spiritual universalism98. The global confluence of heterogeneous movements in the history of internationalism, based on the quest for alternative universal values derived from spirituality and ethics, played an important part in the formation of the UN and UNESCO.

Conclusion

In postwar Japan, spiritual universalisms were either condemned by leftists as Japanese imperialist and racist ideology, or celebrated by rightists as the foundation of Japan’s attempt to liberate Asia from western racism and colonialism. In this article, I have tried to show how the socio-political role of spiritual universalism was transformed in Japan. Though initially providing an ideational ground for criticizing the west’s “racist” treatment of Japan, it gradually lost its universalist aspect, coming to accept violence as a means, and was taken up as part of Japan’s imperialist ideology. Spiritual universalism can promote antiracism, but it can also err into a self-celebrating ideology, placing others in an inferior position in the spiritual hierarchy.

Claude-Olivier Doron, in discussing antiracist criticism in 1830s France, aptly draws our attention to the ambiguity of spiritual universalism99. He takes up the writings of the socialist Constantin Pecqueur and the counter-revolutionary thinker Blanc de Saint Bonnet, who exemplify the first antiracist position against theories of race based on biological inequality. They insist on the primacy of the human spirit over biological determinism, as well the unity of humanity based on the universality of moral and spiritual principles. Simultaneously, however, their principles lead them very clearly to claim moral and spiritual superiority for Europe, and to the concept of spiritual races which are unequal and hereditary. This is a clear case of how the discourse of spiritual universalism can play a double-edged role in racism and antiracism.

From the late nineteenth century to the first half of the twentieth century, Asian and African nationalisms, pan-Asian, pan-African, and pan-Islamist discourses, as well as other antiracist, anti-imperialist solidarity movements100, often drew on various kinds of spiritual universalism for their help in establishing a respectable position for the self, in antinomy to the hierarchical view of race and civilization based on material development. Comparative and connective perspectives on spiritual universalism in Japan and India show that there were indeed important moments of transnational solidarity based on the universality of human spirituality, morality, and aesthetics, which played important roles in anticolonial and antiracist movements, while containing the ambivalent workings of power towards self-aggrandizement.

These various spiritual, moral, and educationist movements in and across various corners of the world played significant roles in supporting the antiracist internationalism of the early twentieth century. The URC was the biggest, though often forgotten event that connected various antiracist movements and ideas from around the world in the early twentieth century. Helen Tilley points out that the URC and other international congresses of the interwar period helped to lay the groundwork for UNESCO’s Statements on Race from the 1950s, and further that “the URC was even more inclusive, regionally and culturally, than any of the ensuing gatherings, providing a platform for more speakers from Africa, Asia, the Middle East, and the Americas than were ever given a voice in the four statements on race issued by UNESCO”101. In other words, the URC’s success was dependent on the wide range of antiracist movements taking place across all regions of the world. The history of antiracism leading to UNESCO’s Statements on Race is geographically wider, chronologically deeper, and ideationally broader than the present Eurocentric secular rationalist presumption allows us to see.

Notes

1

Peter van der Veer, Imperial Encounters: Religion and Modernity in India and Britain, Princeton, N.J., Princeton University Press, 2001; Peter van der Veer, "Spirituality in Modern Society," Social Research: An International Quarterly 76, no. 4, 2009.

2

Sugata Bose and Kris K Manjapra, eds., Cosmopolitan Thought Zones: South Asia and the Global Circulation of Ideas, Houndmills, Palgrave Macmillan, 2010.

3

Sugata Bose, "Different Universalisms, Colorful Cosmopolitanisms: The Global Imagination of the Colonised," in Cosmopolitan Thought Zones: South Asia and the Global Circulation of Ideas, ed. Sugata Bose and Kris K Manjapra, Houndmills, Palgrave Macmillan, 2010, p. 97-98. I would like to add that multiple universalisms not only competed with but also complemented and co-produced each other.

4

There are non-European enlightenments in history, such as the Buddhist and Hindu ones, which are elided when we talk of the modern European enlightenment as the Enlightenment. With this cautionary note, I use the term “Enlightenment” to denote the European enlightenment in this paper in accordance with convention.

5

Homi Bhabha, "Unsatisfied: Notes on Vernacular Cosmopolitanism," in Text and Nation: Cross-Disciplinary Essays on Cultural and National Identities, ed. Laura Garcia-Morena and Peter C. Pfeifer, London, Camden House, 1996; Sugata Bose, "Different Universalisms, Colorful Cosmopolitanisms: The Global Imagination of the Colonised," in Cosmopolitan Thought Zones: South Asia and the Global Circulation of Ideas, ed. Sugata Bose and Kris K Manjapra, Houndmills, Palgrave Macmillan, 2010, p. 97.

6

Jonathon S Kahn and Vincent W Lloyd, Race and Secularism in America, Columbia University Press, 2016.

7

Unequal treaties were signed between Japan and the western powers in the 1850s. One of most important diplomatic aims of the modern Japanese government from 1868 was to revise these treaties. The Japanese government managed to abolish European extraterritoriality and gain partial tariff autonomy in 1894, taking effect from 1899, and gained full tariff autonomy in 1911.

8

Gauri Viswanathan notes “the complex role of occultism in loosening boundaries between closed social networks.” She further argues that “in late nineteenth- to early twentieth-century colonial culture, occultism offered the means for mobility between different personae and world-views otherwise denied or at least circumscribed by the restrictive relations between colonizer and colonized.” Gauri Viswanathan, "Spectrality’s Secret Sharers: Occultism as (Post) colonial Affect," in Beyond the Black Atlantic: Relocating Modernization and Technology, ed. Walter Goebel and Saskia Schabio, London, Routledge, 2006, p. 135. Also see Viswanathan "The Ordinary Business of Occultism," Critical Inquiry 27, no. 1, 2000.

9

For example, there were some tensions between Swami Vivekananda and the Theosophical Society in the US, and Swami Vivekananda and the Maha Bodhi Society of Dharmapala in India, which had a close relationship with the Theosophical Society. Vivekananda says, “There is a report going round that the Theosophists helped the little achievements of mine in America and England. I have to tell you plainly that every word of it is wrong, every word of it is untrue.” Swami Vivekananda, "My Plan of Campaign," in The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda III, Calcutta, Advaita Ashrama, 1989, p. 208. He also writes, “The Theosophists tried to fawn upon and flatter me as I am the authority now in India, and therefore it was necessary for me to stop my work giving any sanction to their humbugs, by a few bold, decisive words; and the thing is done. I am very glad” Swami Vivekananda, "Dear Mrs. Bull, 5th May, 1897," in The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda VII, Calcutta, Advaita Ashrama, 1989, p. 506.

10

Kiyushigen vol. 1, p. 6, quoted in Shin’ichi Yoshinaga and Koichi Nozaki, "Hirai Kinza to Nihon no Uniterianizumu (Hirai Kinza and Japanese Unitarianism)," Maizuru Kōgyō Senmon Gakkō Kiyō (Bulletin of Maizuru National College of Technology) 40, 2005, p. 125.

11

Shin’ichi Yoshinaga, "Hirai Kinza, sono Shōgai (Kinza Hirai: His Life)," in Hirai Kinza ni okeru Meiji Bukkyō no Kokusai-ka ni kansuru Shūkyōshi, Bunkashi teki Kenkyū (Hirai Kinza and the Globalization of Japanese Buddhism of Meiji Era: A Cultural and Religio-HistoricalStudy), ed. Yoshinaga Shin’ichi, 2007, [online].

12

On Dharmapala’s transformation from universalism to nationalism, see Masahiko Togawa, "Darumapāra no Buddagaya Fukkō Undō to Nihonjin: Hindū Kyō Sōinchō no Mahanto to Eiryō Indo Seifu no Shūkyō o Haikei to shita (Japanese and Dharmapala's Buddhist Revival Movement: Hindu Abbot Mahant and the Religion Policy of the British Indian Government)," Nihon Kenkyū 53, 2016.

13

Yoshinaga says, “It is natural that Olcott should count this crusade to Japan among one of the most important events in his life, but the reality was not exactly as he thought. Olcott certainly frightened the Christian missionaries, but he also dismayed the representatives of Buddhism. … Olcott’s second visit to Japan in 1892 seems to have been a failure, though he might not have thought so.” Shin’ichi Yoshinaga, "Japanese Buddhism and the Theosophical Movement, A General View," in Hirai Kinza ni okeru Meiji Bukkyō no Kokusai-ka ni kansuru Shūkyō-shi, Bunka-shi teki Kenkyū (Kinza Hirai and the Globalization of Japanese Buddhism of Meiji Era: A Cultural and Religio-Historical Study), ed. Yoshinaga Shin’ichi, 2007, p. 8, [online]. Shields further points out that “even among so-called progressives and reformists, there were many who were reluctant to embrace Olcott's Buddhism. James Mark Shields, Against Harmony: Progressive and Radical Buddhism in Modern Japan, New York, Oxford University Press, 2017, p. 51.

14

Masahiko Togawa, "Darumapāra no Buddagaya Fukkō Undō to Nihonjin: Hindū Kyō Sōinchō no Mahanto to Eiryō Indo Seifu no Shūkyō o Haikei to shita (Japanese and Dharmapala's Buddhist Revival Movement: Hindu Abbot Mahant and the Religion Policy of the British Indian Government)," Nihon Kenkyū 53, 2016, p. 200.

15

Judith Snodgrass, Presenting Japanese Buddhism to the West: Orientalism, Occidentalism, and the Columbian Exposition, Chapel Hill University of North Carolina Press, 2003, p. 29-34.

16

As Fenollosa studied Buddhist art he began to see Buddhism as having the potentiality of converting and surpassing the intellectual hegemony of the west. Koichi Nozaki, "Hirai Kinza to Fenorosa: Nashonarizumu, Jyaponizumu, Orientarizumu (Kinza Hirai and Fenollosa: Nationalism, Japonism, and Orientalism)," Shūkyō Kenkyū (Journal of religious studies) 79, no. 1, 2005.

17

Kinza Hirai, "The Real Position of Christianity in Japan," in The World's Parliament of Religions: An Illustrated and Popular Story of the World's First Parliament of Religions, Held in Chicago in Connection with the Columbian Exposition of 1893. Vol. 1, ed. John Henry Barrows, Chicago, Parliament Publishing Company, 1893, p. 448.

18

Kinza Hirai, "The Real Position of Christianity in Japan," in The World's Parliament of Religions: An Illustrated and Popular Story of the World's First Parliament of Religions, Held in Chicago in Connection with the Columbian Exposition of 1893. Vol. 1, ed. John Henry Barrows, Chicago, Parliament Publishing Company, 1893, p. 448.

19

Kinza Hirai, "The Real Position of Christianity in Japan," in The World's Parliament of Religions: An Illustrated and Popular Story of the World's First Parliament of Religions, Held in Chicago in Connection with the Columbian Exposition of 1893. Vol. 1, ed. John Henry Barrows, Chicago, Parliament Publishing Company, 1893, p. 444.

20

Kinza Hirai, "The Real Position of Christianity in Japan," in The World's Parliament of Religions: An Illustrated and Popular Story of the World's First Parliament of Religions, Held in Chicago in Connection with the Columbian Exposition of 1893. Vol. 1, ed. John Henry Barrows, Chicago, Parliament Publishing Company, 1893, p. 445.

21

Kinza Hirai, "The Real Position of Christianity in Japan," in The World's Parliament of Religions: An Illustrated and Popular Story of the World's First Parliament of Religions, Held in Chicago in Connection with the Columbian Exposition of 1893. Vol. 1, ed. John Henry Barrows, Chicago, Parliament Publishing Company, 1893, p. 450.

22

John Henry Barrows, The World's Parliament of Religions: An Illustrated and Popular Story of the World's First Parliament of Religions, Held in Chicago in Connection with the Columbian Exposition of 1893, Vol. 1, Chicago, Parliament Publishing Company, 1893, p. 115-116, parenthesis added.

23

Kinza Hirai, "Synthetic Religion," in Neely’s History of the Parliament of Religions, ed. Walter R. Houghton, Chicago, F. T. Neely, 1893, p. 161. The original phrase in Rinzairoku (Records of Rinzai) says, “If you meet a Buddha, kill the Buddha.”

24

Hirai’s view of “Synthetic religion,” which went beyond the existing Buddhist framework, later led to conflicts with Buddhist institutions in Japan and Hirai chose to embrace Unitarianism. Koichi Nozaki, "Hirai Kinza to Yuniterian (Kinza Hirai and Unitarian)," in Hirai Kinza ni okeru Meiji Bukkyō no Kokusai-ka ni kansuru Shūkyō-shi, Bunka-shi teki Kenkyū (Kinza Hirai and the Globalization of Japanese Buddhism of Meiji Era: A Cultural and Religio-Historical Study), ed. Shin’ichi Yoshinaga, 2007, [online]. On his return to Japan in 1894, Hirai taught English at his Oriental Hall in Kyoto and then at the Tokyo School of Foreign Languages as a professor, and supported the activities of the Japan-India Association (1903-), while also being active as a Unitarian. After he left Unitarianism he was involved in the study of psychical phenomena and practiced Zen-like meditation in the ‘Samadhi Association’ (Sanmajikai). Shin’ichi Yoshinaga, "Hirai Kinza, sono Shōgai (Hirai Kinza: His Life)," in Hirai Kinza ni okeru Meiji Bukkyō no Kokusai-ka ni kansuru Shūkyō-shi, Bunka-shi teki Kenkyū (Kinza Hirai and the Globalization of Japanese Buddhism of Meiji Era: A Cultural and Religio-Historical Study), ed. Shin’ichi Yoshinaga, 2007, [online].

25

John Henry Barrows, The World's Parliament of Religions: An Illustrated and Popular Story of the World's First Parliament of Religions, Held in Chicago in Connection with the Columbian Exposition of 1893, Vol. 1, Chicago, Parliament Publishing Company, 1893, p. 165-166.

26

The Buddhist delegates attended the parliament on a voluntary basis and not as official representatives as there was never consensus among the Buddhists in Japan on whether they should send delegates. On discussion in the Japanese Buddhist community regarding the value of sending representatives to the parliament, see Judith Snodgrass, Presenting Japanese Buddhism to the West: Orientalism, Occidentalism, and the Columbian Exposition, Chapel Hill University of North Carolina Press, 2003, p. 173-4 and Mitsuya Dake, "Shikago Bankoku Shūkyō Kaigi to Mieji Shoki no Nihon Bukkyō-kai: Shimaji Mokurai to Yatsubuchi Banryu no Dōkō o tōshite (The World's Parliament of Religion in Chicago in 1894 and Japanese Buddhism in late 19th Century)," Ryukoku Daigaku Kokusai Shakai Bunka Kenkyūjyo Kiyō (Journal of the Socio-Cultural Research Institute, Ryukoku University: Society and Culture) 13, 2011.

27

Naoko Frances Hioki, "Hirai Kinza to Shikago Bankoku Shūkyō Kaigi (Hirai Kinza and the Chicago Parliament of the World's Religions)," Manuscript read at the online Workshop on the Globalization of Zen, 20th June 2020.

28

Snodgrass points out that “Japan’s primary project at the fair was to challenge this Western presupposition of cultural superiority and protest the lowly position assigned to the Japanese in the hierarchy of evolutionary development.” In fact, the “Columbian Exposition was consciously organized to present an ‘object lesson’ in Social Darwinism displaying the rightful place of the people of the world in the hierarchy of race and civilization.” Judith Snodgrass, Presenting Japanese Buddhism to the West: Orientalism, Occidentalism, and the Columbian Exposition, Chapel Hill University of North Carolina Press, 2003, p. 2. This is related not only to international relations but also racism against ethnic minorities in the US. It is telling that the World's Columbian Exposition had the racist policy of not allowing “Colored Americans” to officially participate.

29

Gozo Tateno and Augustus O. Bourn, "Foreign Nations at the World's Fair," The North American Review 156, no. 434 (Jan.), 1893, p. 43, parenthesis added.

30

Hirai had exchanged letters with Tateno at Washington, D.C. before attending the parliament. In contrast to Hirai’s enthusiasm, Tateno’s replies were somewhat bureaucratic, declining to provide any information regarding diplomatic policy, advising him to give lectures at state capitals other than Washington, D.C., and asking him to contact the New York consulate for resources. Kohei Takase, "Jōyaku Kaisei to Shūkyō: 1893nen Shikago Bankoku Shūkyō Kaigi Niokeru Hirai Kinza No Enzetsu (Treaty Revision and Religions: Rethinking the Speech of Kinza Hirai in the World's Parliament of Religions in Chicago, 1893)," Tokyo Daigaku Shūkyōgaku Nenpō (Annual Review of Religious Studies) 37 (2020). These letters and other records regarding Kinza Hirai were kept by Mrs. Fugura Harayama. I would like to thank Mrs. Harayama for allowing me to use these resources.

31

Naoko Frances Hioki, "Hirai Kinza to Shikago Bankoku Shūkyō Kaigi (Hirai Kinza and the Chicago Parliament of the World's Religions)," Manuscript read at the online Workshop on the Globalization of Zen, 20th June 2020; Kohei Takase, "Jōyaku Kaisei to Shūkyō: 1893nen Shikago Bankoku Shūkyō Kaigi Niokeru Hirai Kinza No Enzetsu (Treaty Revision and Religions: Rethinking the Speech of Kinza Hirai in the World's Parliament of Religions in Chicago, 1893)," Tokyo Daigaku Shūkyōgaku Nenpō (Annual Review of Religious Studies) 37, 2020.

32

Naoko Frances Hioki, "Hirai Kinza to Shikago Bankoku Shūkyō Kaigi (Hirai Kinza and the Chicago Parliament of the World's Religions)," Manuscript read at the online Workshop on the Globalization of Zen, 20th June 2020. Afterwards, however, Hirai, Vivekananda, and Dharmapala went on to take different positions vis-à-vis the religions they represented at the parliament. Hirai distanced himself from Buddhism, while Vivekananda advocated Vedanta, and Dharmapala promoted Sinhalese Buddhist nationalism.

33

Swami Vivekananda, "The Speech of Mr. Vivekananda," in The World's Parliament of Religions: An Illustrated and Popular Story of the World's First Parliament of Religions, Held in Chicago in Connection with the Columbian Exposition of 1893. Vol. 1, ed. John Henry Barrows, Chicago, Parliament Publishing Company, 1893, p. 102.

34

Swami Vivekananda, "Hinduism," in The World's Parliament of Religions: An Illustrated and Popular Story of the World's First Parliament of Religions, Held in Chicago in Connection with the Columbian Exposition of 1893. Vol. 2., ed. John Henry Barrows, Chicago, Parliament Publishing Company, 1893, p. 977.

35

On Vivekananda at the Chicago parliament, see Kuniko Hirano, "Vivēkānanda no Hindū Kyō: 1983 nen Bankoku Shūkyō Kaigi deno Enzetsu o Megutte (The Hinduism of Vivekananda: As Revealed in the Chicago World Parliament of Religions of 1893)," Minami Ajia Kenkyū (Journal of Japanese Association for South Asian Studies) 21, 2009.

36

When asked about the results of the parliament of religions, Vivekananda said, “The Parliament of Religions, as it seems to me, was intended for a 'heathen show' before the world: but it turned out that the heathens had the upper hand and made it a Christian show all around. So the Parliament of Religions was a failure from the Christian standpoint, seeing that the Roman Catholics, who were the organisers of that Parliament, are, when there is a talk of another Parliament at Paris, now steadily opposing it. But the Chicago Parliament was a tremendous success for India and Indian thought. It helped on the tide of Vedanta, which is flooding the world.” Swami Vivekananda, "The Abroad and the Problems at Home (The Hindu, Madras, February, 1897)," in The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda V, Calcutta, Advaita Ashrama, 1989, p. 211.

37

On the interaction between Okakura, Vivekananda, and Tagore, see Yoshiko Okamoto, "Indo ni okeru Tenshin Okakura Kakuzō: 'Ajia' no Sōzō to Nashonarizumu ni kansuru Oboegaki (The Discovery of “Asia”: Okakura Kakuzō in Colonial India)," in Kindai Sekai no 'Gensetsu' to 'Ishō': Ekkyō teki Bunka Kōshō gaku no Shiten kara (Discourses and Images of the Modern World : From the Perspective of Cultural Interaction Studies), ed. Kenichiro Aratake and Junko Miyajima, Suita, Kansai Daigaku Bunka Kōshō gaku Kyōiku Kenkyū Kyoten, ICIS (The Institute for Cultural Interaction Studies, Kansai University), 2012; Yoshiko Okamoto, "Bukkyō o meguru Dōshōimu no Tabiji, Okakura Kakuzō to Suwāmī Vivēkānanda no Deai to Betsuri (The Journey Together and Apart surrounding Buddhism: The Meeting and Separation of Kakuzo Okakura and Swamiji Vivekananda)," in Okakura Tenshin: Dentō to Kakushin (Tenshin Okakura: Tradition and Innovation), ed. Okakura Tenshin Kenkyū Han (Okakura Tenshin Research Group), Tokyo, Daito Bunka Daigaku Tōyō Kenkyūjo (Institute for Oriental Studies of Daito Bunka University), 2014.

38

Swami Vivekananda, "My Plan of Campaign," in The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda III, Calcutta, Advaita Ashrama, 1989; Swami Vivekananda, "The Sages of India," in The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda III, Calcutta, Advaita Ashrama, 1989. On Vivekananda’s changing stance vis-à-vis Buddhism, see Kuniko Hirano, "Vivēkānanda no Budda kan: Hindū kyō Fukkō Undō ni okeru Rinen o Megutte (Vivekananda’s Views on the Buddha: Concerning the Revival of Hinduism)," Jōchi Ajia gaku (The Journal of Sophia Asian Studies) 29, 2011; Masahiko Togawa, "Suwāmī Vivēkānanda ni okeru Shūkyō to Nashonarizumu: Bukkyō to Hindūkyō no Kankei o tōshite mita (Swami Vivekananda’s Views on Religion and Nationalism: With special reference to the Relation between Buddhism and Hinduism)," Minami Ajia Kenkyū (Journal of Japanese Association for South Asian Studies) 29, 2017.

39

Swami Vivekananda, "The Sages of India," in The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda III, Calcutta, Advaita Ashrama, 1989, p. 265.

40

Swami Vivekananda, "Dear Mrs. Bull, 5th May, 1897," in The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda VII, Calcutta, Advaita Ashrama, 1989, p. 505.

41

Swami Vivekananda, "Dear Mrs. Bull, 5th May, 1897," in The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda VII, Calcutta, Advaita Ashrama, 1989, p. 506.

42

Swami Vivekananda, "My Dear Swarup, 9th February, 1902," in The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda V, Calcutta, Advaita Ashrama, 1989, p. 173.

43

Vivekananda wrote in his last letter to Ms. MacLeod: "You have been a good angel to me." See: "Chapter Six: The Devotee as Friend of Swami Vivekananda" in Swami Vidyatmananda: The Making of a Devotee, para 2, [online].

44

On June 25, 1902, Indian Mirror, an Indian newspaper, published an article advertising the Asian Parliament of Religions in Kyoto, named the Prajna Paramita Conference. The Maha Bodhi Society also published an article welcoming the Asian Parliament of Religions in The Maha Bodhi Journal in July 1902. Masahiko Togawa, "Darumapāra no Buddagaya Fukkō Undō to Nihonjin: Hindū Kyō Sōinchō no Mahanto to Eiryō Indo Seifu no Shūkyō o Haikei to shita (Japanese and Dharmapala's Buddhist Revival Movement: Hindu Abbot Mahant and the Religion Policy of the British Indian Government)," Nihon Kenkyū 53, 2016, p. 192.

45

Out of fun, Vivekananda endearingly addressed Okakura as ‘Kura’, approximating to ‘Khurhā’ in Bengali, meaning uncle. Swami Vivekananda, "My Dear Rakhal (12th February 1902)," in The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda V, Calcutta, Advaita Ashrama, 1989, p. 176.

46

Masahiko Togawa, "Eiryō Indo ni okeru Okakura Tenshin no Buddagaya Hōmon nitsuite: Suwāmī Vivēkānanda to Rabindoranāto Tagōru tono Kōryū kara (Okakura Tenshin (Kakuzo) at Bodh Gaya during His Stay in British India: Examination Using the Records Exchanged between Swami Vivekananda and Rabindranath Tagore)," Ajia Afurika Gengo Bunka Kenkyū (Journal of Asian and African Studies) 92, 2016.

47

Swami Vivekananda, "Buddhism, the Fulfilment of Hinduism," in The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda I, Calcutta, Advaita Ashrama, 1989, p. 21, 23.

48

Swami Vivekananda, "Buddhism, the Fulfilment of Hinduism," in The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda I, Calcutta, Advaita Ashrama, 1989, p. 23. Parenthesis added.

49

Swami Vivekananda, "The Abroad and the Problems at Home (The Hindu, Madras, February, 1897)," in The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda V, Calcutta, Advaita Ashrama, 1989, p. 217.

50

Swami Vivekananda, "The Abroad and the Problems at Home (The Hindu, Madras, February, 1897)," in The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda V, Calcutta, Advaita Ashrama, 1989, p. 210.

51

Swami Vivekananda, "My Dear Swarup, 9th February, 1902," in The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda V, Calcutta, Advaita Ashrama, 1989, p. 172.

52

Swami Vivekananda, "My Dear Swarup, 9th February, 1902," in The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda V, Calcutta, Advaita Ashrama, 1989, p. 172.

53

Vivekananda, "Epistles CXV (A letter to Mrs. Ole Bull and her daughter, 10th February, 1902)," in The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda V, Calcutta, Advaita Ashrama, 1989, p. 175.

54

Swami Vivekananda, "My Dear Swarup, 9th February, 1902," in The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda V, Calcutta, Advaita Ashrama, 1989, p. 173; Swami Vivekananda, "Buddhism, the Fulfilment of Hinduism," in The Complete Works of Swami Vivekananda I, Calcutta, Advaita Ashrama, 1989, p. 23.

55

Tenshin Okakura, The Ideals of the East, with special reference to the Art of Japan, London, John Murray, 1903, p. 1.

56

Tenshin Okakura, The Awakening of Japan, New York, Century, 1904, p. 107.

57

Tenshin Okakura, The Awakening of Japan, New York, Century, 1904.

58

Yasuko Takezawa, "Transcending the Western Paradigm of the Idea of Race," The Japanese Journal of American Studies 16, 2005, p. 9.

59

Rabindranath Tagore, On Oriental Culture and Japan's Mission, Tokyo, Indo-Japanese Association, 1929, p. 1-2. This lecture was delivered by Tagore to the Indo-Japanese Association at the Industrial Club, Tokyo, on May 15, 1929.

60

Cemil Aydin, The Politics of Anti-Westernism in Asia: Visions of World Order in Pan-Islamic and Pan-Asian Thought, New York, Columbia Univ Press, 2007.

61

Prasenjit Duara, "The discourse of civilization and pan-Asianism," Journal of World History 12, no. 1, 2001, p. 110; Bunzō Hashikawa, "Japanese Perspectives on Asia: From Dissociation to Coprosperity," in The Chinese and the Japanese: Essays in Political and Cultural Interactions, ed. Akira Iriye, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1980, p. 331–341.

62

Shin'ichi Yamamuro, Shisōkadai to shite no Ajia: Kijiku, Rensa, Tōki (Asia as a Philosophical Agenda: Axis, Linkage and Projection), Tokyo, Iwanami Shoten, 2001, p. 625.

63

Naoko Shimazu, Japan, Race and Equality: The Racial Equality Proposal of 1919, London, Routledge, 1998, p. 20.

64

Naoko Shimazu, Japan, Race and Equality: The Racial Equality Proposal of 1919, London, Routledge, 1998, p. 27.

65

As Smuts (British empire) and Hysman (Belgium) were absent, seventeen out of nineteen members voted. Those who voted for the amendment were Japan (2), France (2), Italy (2), Brazil (1), China (1), Greece (1), Serbia (1), and Czechoslovakia (1), while the votes of the British empire, the US, Portugal, Poland and Romania were not registered. Naoko Shimazu, Japan, Race and Equality: The Racial Equality Proposal of 1919, London, Routledge, 1998, p. 27.

66

Naoko Shimazu, Japan, Race and Equality: The Racial Equality Proposal of 1919, London, Routledge, 1998, p. 27.

67

Naoko Shimazu, Japan, Race and Equality: The Racial Equality Proposal of 1919, London, Routledge, 1998, p. 16; Shin'ichi Yamamuro, Shisōkadai to shite no Ajia: Kijiku, Rensa, Tōki (Asia as a Philosophical Agenda: Axis, Linkage and Projection), Tokyo, Iwanami Shoten, 2001, p. 625.

68

Naoko Shimazu, Japan, Race and Equality: The Racial Equality Proposal of 1919, London, Routledge, 1998, p. 51-2.

69

Naoko Shimazu, Japan, Race and Equality: The Racial Equality Proposal of 1919, London, Routledge, 1998, p. 4.

70

Naoko Shimazu, Japan, Race and Equality: The Racial Equality Proposal of 1919, London, Routledge, 1998, p. 116.

71

Prasenjit Duara, "The discourse of civilization and pan-Asianism," Journal of World History 12, no. 1 , 2001, p. 110.

72

Rabindranath Tagore, Nationalism, San Francisco, The Book Club of California, 1917, p. 72, 73-4.

73

Rabindranath Tagore, Nationalism, San Francisco, The Book Club of California, 1917, p. 117.

74

Rabindranath Tagore, Nationalism, San Francisco, The Book Club of California, 1917, p. 118.

75

Rabindranath Tagore, Nationalism, San Francisco, The Book Club of California, 1917, p. 131-2.

76

Rabindranath Tagore, Nationalism, San Francisco, The Book Club of California, 1917, p. 133.

77

Shin’ichi Yoshinaga, "Okawa Shumei, Pōru Rishāru, Mira Rishāru aru Kaikō (Okawa Shumei, Paul Richard and Mirra Richard: an encounter)," Maizuru Kōgyō Senmon Gakkō Kiyō (Bulletin of Maizuru National College of Technology) 43, 2008.

78