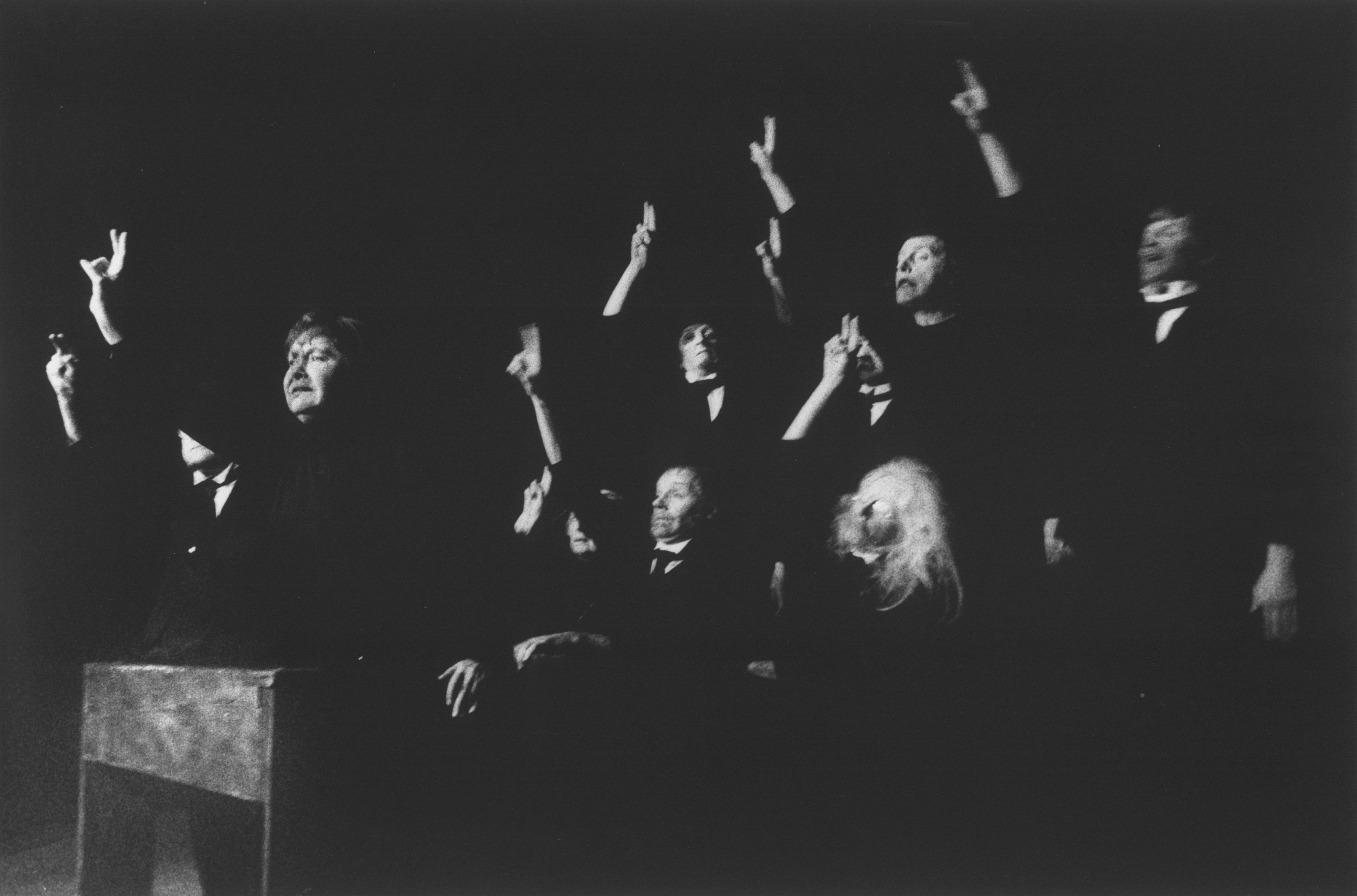

Romano Martinis, La Classe morte de Tadeusz Kantor (1975)

National (Heroic) Memory and Individual Identity in the Czech Republic

In March 2018, a pensioner asked to see me in my capacity of Advisor to the Director at the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes in Prague. Seventy-year old Richard Mariáš wanted to tell me his story1. In 1984, he was a civilian pilot in the Czechoslovak airlines, ČSA. On a Bratislava-Prague flight, his plane was kidnapped by a citizen who wanted to defect to the West. He helped the police capture the defector and thus gained the positive attention of the security services (StB.) Soon thereafter, two civilian agents appeared at his door and invited him to collaborate with the secret police2. “What did you say?”, I asked. “You know very well the answer”, he told me. “Which means?”, I asked. “Which means of course I said yes. I had two small kids and a good job, I couldn’t risk them firing me.” I nodded.

However, he told me he did not like this regime and was no communist party member. He agreed to collaborate out of fear but hated himself for not daring to resist. So, he resolved to offset his moral failure. He had family in the US that the regime did not know of. He got in touch with them, had them contact American authorities, and was eventually recruited, due to chance circumstances, not by the CIA but by the FBI. He told me his double spying activity consisted of taking pictures and drawing aerial maps from the American bases in West Germany (for the StB) and of diverting three twelve-kilogram bags of Czechoslovak diplomatic mail and forwarding them to the US (for the FBI).

In 2011, a Czech law endeavored to acknowledge and compensate “heroes of the anti-communist resistance”3. He applied for this status but was bitterly disappointed when it was denied to him because of his past collaboration with the secret police4. So, he came to see me, a historian, as a last resort to get if not formal justice, then at least recognition and empathy for his path. This article's aim is not to verify his story, but his plight does illustrate the individual's need for historical justice.

This article first endeavors to show that the Czech process of decommunization favored punishment over reconciliation, be it through the legal apparatus developed after 1989 or via the narrative and initiatives of selected political elites and former dissidents. It shows that this narrative was promoted for political gain rather than historical justice, and reflects on whether transitional justice is possible at all. Second, it shows that the dominant anticommunist narrative provided substantial professional capital to the history entrepreneurs who promoted it. And finally, the article reflects on commemorations and public history. It draws from Czech films and public television to point to an alternative narrative that is perhaps nearer to the preoccupations of the wider public. All throughout, it questions the notion of heroism.

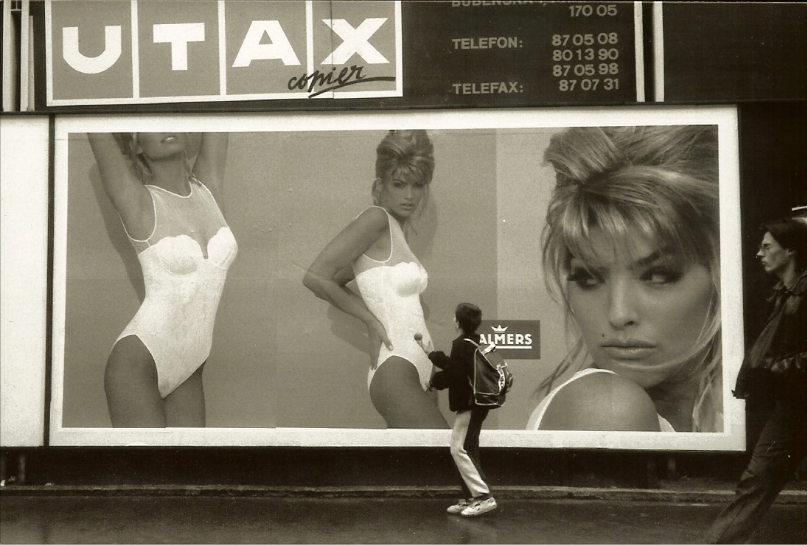

Demonstration on Old Town Square, Prague, 1991.

From National Memory to Individual Identity

As John Bodnar showed in the case of the Second World War in America, the battle over the national memory of a specific event is not so much about history as it is about national identity5. A nation’s past behavior is rarely exemplary: “Proclamations of virtue … could never fully erase … personal qualms about encounters with violence and trauma”6. Comprehension is never a settled matter and the past is a topic of dispute as much as it is a “subject of public performances in rituals, commemorations, and various political and cultural expressions”7. Public forms of remembering are not about the past but about the present.

Zdena Salivarová, a famous Czech writer and publisher, almost singlehandedly saved Czech literature from oblivion by creating her own publishing house, Sixty-Eight Publishers, in her Canadian exile. She also was a longtime friend of Václav Havel’s. In 1990, immediately after the Velvet Revolution, the newly elected president awarded her the Order of the White Lion, Czechoslovakia’s highest order. But her name was discovered on a list of secret police collaborators that was smuggled out of the Ministry of Interior and published without official endorsement in 19928. From hero, she became overnight a traitor in her anticommunist circle, although her family had been persecuted after 1948 and her brother had served a fifteen-year forced labor sentence in the infamous uranium mines. She fell into depression and her husband, world-famous writer Josef Škvorecký, wrote a novel to depict her sorrow9. As a young woman, she had indeed agreed to spy on a female friend who was dating a Bulgarian national because she was too scared to refuse the secret police’s request. She wrote two meaningless reports in 1958 in which she tried not to endanger her in any way, and thereafter was left alone – until 1992.

Richard Mariáš and Zdena Salivarová are two examples of individuals who are convinced they fought the communist regime without getting the social recognition they deserve. Indeed, they felt they were shamed in a way that they did not deserve. One is famous, the other is a private citizen, one’s fame was depreciated in 1992, the other’s heroic status was denied in 2015. One was condemned only morally and socially, the other one was officially rebuffed by the state. One (Salivarová) sued the Ministry of Interior and had her record erased, the other did not. But both are convinced to have patriotically fought for a country that has rejected them and neither benefited from much public empathy, which added to their distress10.

To pass a fair judgment on them, one would have to examine their situation in its historical setting. But neither post-communist politicians nor the justice system have so far risen to the task. As to historians, it is mainly the militant anticommunists among them who have raised the issue of transitional justice, often in a moralizing way11. Normative and prago-centric evaluations of the communist past have overdetermined the identity of Czech citizens and authoritatively divided them into heroes, victims, and traitors. This narrative permeates the public sphere, first and foremost the written press, which is conservative with the exception of the communist daily successor, Právo, and a new outlet called Deník N (founded in 2018.) It is prevalent, although not exclusive, in audiovisual media, be it on news programs of the Czech national television or radio, for instance the oft-quoted programs of political journalist Barbora Tachecí, or the internet channel DVTV founded by two former journalists of Czech Television, Daniela Drtinová and Martin Veselovský. It is present in weeklies, for instance the influential Respekt, an intellectual periodical founded immediately after the regime fall by former dissidents. It dominates social media and the popular blogs attached to the website of the main newspapers, Lidové noviny and Dnes. It is the narrative of the NGOs that work as memorial institutions, i.e. that collect oral history testimonies from the communist and Nazi times, such as Post Bellum. It is the narrative of Act 181/2007, which created the national memory institute, the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes. It is the narrative that infuses the newly created Museum of Twentieth-Century Memory, the first museum of the communist period sponsored by public means, in this instance the city of Prague, which is due to open its first exhibit in 2021. And it is the narrative consistently supported by parliament in all of its laws concerning the communist past since 1990.

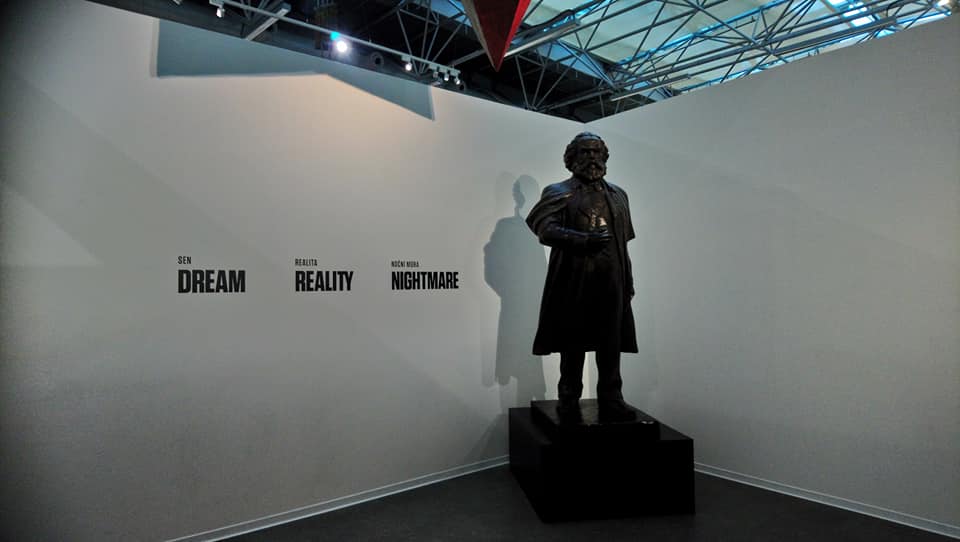

Entrance of the Museum of Communism, Prague, 2019.

Justice Trumped Reconciliation

The process of decommunization was promoted at the expense of its social dimension and historical contextualization12. The option to achieve national reconciliation was sacrificed on the judicial altar. Reconciliation would have translated into the collective ability to hear the story of the “other side”, to accept other narratives than one’s own as belonging to national history, too. Instead, as Roman David notes, “justice without reconciliation acquired a meaning of triumph and domination over the forces of the past”13. It set an expectation concerning the symbolic end of the previous regime “in which anyone connected with that regime should be ‘finished’ by being dismissed, punished, or excluded from the public eye”14.

This policy excluded people like Richard Mariáš and Zdena Salivarová from the national narrative as if they had been as baleful as the worst apparatchiks of the regime15. The list of secret police collaborators was not used to the prospect of reconciliation but as a “proxy for justice”16; the exposure of former informants became a means of shaming and socially isolating them, not of understanding the past17. The historical evidence contained in secret police archives was mobilized in the same retributive manner: as the Constitutional Court remarked, their partial opening in 1996 was primarily motivated by the aim to provide the people “persecuted by the repressive totalitarian state” the evidence necessary for judicial proceedings, for instance rehabilitation, lustration or property restitution18. Only in 2004, fifteen years after the fall of communism, did a new law on archival access explicitly aim at making the records “accessible to researchers for needs of knowledge of the past as a prerequisite for social self-reflection”, with the implicit aim to “humanize history”19.

Czech official memory politics have constructed after 1989 a contrived anticommunist identity which, as Veronika Pehe shows, has been consistently preoccupied with discovering heroes20. Yet the post-communist Czechoslovak state accepted the continuity of the juridical order inherited from the communist period: all laws and treaties remained principally valid until explicitly abrogated, while the communist regime was simultaneously designated as “illegal and criminal”21. The Constitutional Court established that the continuity of “old laws” did not hinder a “discontinuity in values” nor signify the “recognition of the legitimacy of the communist regime”. Legality could not “become a convenient substitute for an absent legitimacy”22. Petr Uhl was one of the rare pundits to question the coherence between these two legal stances23.

As Sławomir Sierakowski24 and Kristen Ghodsee25 have argued, this anti-communist policy has also, and perhaps mainly, served to discredit the left: in Visegrád Europe, the political landscape has shifted in the past thirty years from “right against left” to “right against wrong”. What is at stake is not history but identity and politics. In this process, the national narrative has taken the place of individual identity at the risk of maiming it.

The Cibulka List

The list of collaborators which Salivarová found her name on was made public in 1992. It was published without ethical concerns by a conspiracist and anticommunist activist, Petr Cibulka. It threw to public consumption the names of the people who had allegedly collaborated with the secret police without providing any context or even specifying what the alleged collaboration had consisted of and how long it might have lasted; there were only names and birthdates. The intent of the activists who took the list from the Ministry of Interior archives to pass it on to Cibulka was to shame some of the officials now involved in the transitional regime. These activists were displeased to see some of the new leaders sail unscathed through a vetting process hastily put together while many files conspicuously disappeared. Nadya Nedelsky describes how Petr Toman, member of the 17 November Commission put together to investigate the beating of the students on the first day of the 1989 revolution, as well as screen the new officials, publicly denounced in March 1991, in a televised Federal Assembly session, ten MPs who had declined to step down despite the evidence uncovered by the Commission. “Toman stated that ‘the only way to prevent blackmail, the continued activity of the StB collaborators, and a series of political scandals that could surface at crucial moments is to clear the government and legislative bodies of these collaborators’26”. It was revealed in 2011 that one of the persons that conspicuously disappeared from the list of collaborators was none other than Petr Cibulka’s mother27.

Because these archives were still closed to the public, the individuals who felt wrongly castigated when finding their name on the list could not defend themselves. Having no access to their own file, their only resort was to sue the Ministry of Interior, which many found intimidating, too complicated, and/or unaffordable. Of those who did sue, 80 % to 90 % won their case28.

The main source of bitterness for people at the time was not so much the injustices of the Stalinist era, which had also hit communists, as the small-scale, everyday humiliations they had experienced under the regime of normalization from 1968 to 1989. The country had been invaded by the Warsaw Pact countries and the regime was determined to reestablish order and orthodoxy. Ascertaining the mood of the population, and thereby the real state of opposition became a crucial task for the secret police. As an example of chicanery, a French friend of mine who spent the normalization years in Prague married a Czech citizen. In the 1980s she befriended people who were close to the dissident circles and she also had a toddler and a newborn baby, who was seriously ill. In order to care for him, she knew she would have to give up her job at the end of her maternity leave – and the protective French diplomatic passport that came with it. Her annual visa was to expire soon, and she was summoned to the police for foreigners. She was informed that she had failed to ask for her visa renewal on time and would be expelled back to her home country. “But what about the children?”, she asked. “The children will stay here, of course”, answered the secret policeman. Sick to her stomach, she understood in a flash that the next step would be the proposal to exchange a prolongation of her visa against her collaboration with the secret police. She was saved by the French embassy, who prolonged her diplomatic passport even without employing her. This is but one example of how low-level StB civil servants blighted the lives of ordinary people.

The Cibulka list remains the only form of redress that many people were granted concerning the communist past. Although symptomatic of an insensitive policy of dealing with the past, it provided for many a source of satisfaction by exposing the names of some of the people who had damaged the social fabric: not the civil servants themselves (many of whom did get fired after 1989 although they also enjoyed full pensions) but at least the neighbors, colleagues, friends, and passersby who had exercised in their name relentless everyday surveillance. This was tangible moral retribution. Moreover, in the frame of the lustration law that was adopted in 1991 to screen the new officials from collaboration with the secret police or from a high-ranking position in the communist party, any citizen was entitled to prompt the investigation of a senior official for a deposit of 1,000 crowns (about 40 euros), which they would recover if the official was indeed dirty29.

It is difficult not to see in this vindictive collective denunciation that took no account of mitigating circumstances a symmetry with past communist practices. One of the features of the communist regime had been to encourage its population to publicly expose and denounce others. It was no good omen to see such practices immediately replicated by the new democracy. Moreover, the files of the secret police are widely opened since 2007. There are no restrictions concerning access and privacy and people can still be, and regularly are, publicly exposed. As Nadya Nedelsky30 and Marci Shore31 have underlined it, it means that all aspects of the compromising material gathered against the dissidents, including details of their love lives and sexual indiscretions, are available for full public viewing – which prolongs the influence of the communist secret police to this day. The new democracy lacks a basic ethical codex, just like the communist regime did.

The Impossibility of What We Are Wrestling With

Giving priority to justice over reconciliation was legitimate in 1990, but it augured of an interest in politics rather than societal well-being. It divided Czechoslovak, then Czech, society, all the more so that it discredited from the outset any attempt to consider individual and collective mitigating circumstances. Its advancement brought neither reconciliation nor justice and thus delegitimized both politics and the justice system. The individuals whose trajectory did not fit in a Manichean scenario pitting the “bad communists” against the “good people” were symbolically excluded from society and their suffering was ignored.

One of the reasons why the judicial system proved incapable of holding up to the ambitious task of soothing a country just exiting a forty-year dictatorship is that the judges had been trained under communism and many were reluctant to indict or convict their former leaders. Judge Radomíra Veselá is a case in point. Member of the communist party until 1990, she presided over the trial of Alois Grebeníček, father of Miroslav Grebeníček, who was in the 1990s leader of the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia. The trial was put off on multiple occasions after Grebeníček, one or another of his fellow defendants, and even his lawyer complained of health problems. Thanks to this delaying tactic32, the defendant peacefully died at home in 2003 before his trial could even open. The Bureau of Investigation of the Crimes of Communism created in 1991 to indict communist criminals has had only ten individuals sentenced and only a few really imprisoned33. The longest passed sentence is seven years.

Indeed, transitional justice is a more or less impossible task by principle. When a dictatorial regime falls, the continuity of the state has to prevail. The regime that takes over needs a justice system, a police force, an administration, border guards, political and diplomatic personnel. It cannot afford to fire from one day to the next all the civil servants who should be fired if justice or even morality was the sole criterion by which they were evaluated. It cannot fire the prosecutors, judges, and lawyers appointed by the previous regime because it now needs prosecutors and judges to put the former elites on trial and it needs lawyers to defend them34. It cannot fire the policemen nor the soldiers because it needs a police force and an army to defend itself against the possible return of the former regime and against external enemies. It cannot fire all teachers, accountants, and secretaries, because it needs teachers, accountants, and secretaries in the new state. Yet everyone remembers what everyone else did under communism. Julian Barnes exposed this continuity vs. rupture issue in his tale of the fictitious post-communist trial of the last Bulgarian communist leader, a trial in which the accused intimately knows all the protagonists, first and foremost the prosecutor general: “You are Stoyo Petkanov?”, asks the latter at the opening of the trial. “You know I am. I fought with your father against the Fascists. I sent you to Italy to buy your suit. I approved your appointment as professor of law. You know very well who I am. I wish to make a statement”35.

To paraphrase Berthold Brecht36, the new state simply cannot fire its own population, no matter how compromised it might have been with a dictatorship that lasted for generations and in which there was no end in sight until the eleventh hour. The Czechoslovak Communist Party met on the morning of 17 November 1989 to discuss economic planning until the year 2000. By evening, the revolution was unfolding and within a month the regime was ousted: this is how unexpected the end was. The new elites, the old elites, and the population were thrown together in this post-communist entropy. The new elites could only hope that a sufficient percentage of the population would endorse the new political order and quietly convert to its values. There is no scenario of dictatorship exit in which many people have not been frustrated, many injustices failed to be redressed, and many victims never acknowledged. Moreover, the economy had to be drastically reorganized, a daunting task that created fresh forms of injustice.

In East Central Europe there is only one exception to this course of events: it is the former German Democratic Republic (GDR), for the simple reason that the East German state ceased to exist in 1990 – it was dissolved and its five Länder joined the already existing state of Federal Germany. There was no state left to defend, and hence no state secret to hide, no archives to keep shut, and no former elites to protect. It was also the only country in the region that benefited from massive financial aid – from the Federal Republic. Judges, policemen, soldiers, teachers, and any other compromised person who needed to be fired was indeed fired because there were judges, policemen, soldiers, and teachers immediately available to replace them. They also spoke the same language.

The level of indictment and sentencing reached incomparable proportions compared to other countries. Some 23,000 cases involving crimes committed in the former GDR, “from doping of athletes to mistreatment of prisoners, but excluding any cases involving death or murder” were presented to a judge, and 16,494 sentences handed down by the year 200037. Careers were redressed, injustices were addressed, financial compensations were handed out, properties were restituted. Billions of Deutschmarks were redistributed.

And yet many former GDR citizens remained frustrated and dissatisfied, and they long felt that justice had not been served. Even there, in this model state of transitional justice, “Of the more than 91,000 full-time Stasi officers in 1989, 33 were sentenced by the year 2000. 28 of the sentences were suspended, four were settled financially. Only one of the full-time workers of the largest secret police per capita in world history went to jail – an unassuming watchman at a district office in the countryside, who, after having had too much vodka, drew his weapon and shot two people near the remote outpost. (He) was sentenced in 1990 to ten years in prison”38.

The task was quasi-impossible, and the other countries did what they could with the scarce means they had at their disposal. That the populations were not impressed with the achievements of transitional justice is no surprise; what is perhaps more intriguing is the Czech political choice to sacrifice any form of reconciliation to this unattainable judicial ideal. I will now study the underlying role of history activists at the state level.

The Unfulfilled Promises of Post-Communism.

Political and Professional Capital

Jurists and economists strained to adapt to the rapidly changing state policy, and they did their best to support it. So did historians. But let me contend from the outset that there is no such thing as “the historical truth”. What we have is a narrative of the past, that constructs a story that makes sense for us today out of events that (probably) happened. Even more importantly, this narrative makes sense of our present. The past serves as an explanation for today’s situation. It is a construction that is “highly rhetorical and performative”39. Kendal Phillips suggests that “such performances contain an unsteady mix of reality and dreams. They are generally tangled versions of what actually happened and some mythical or hopeful view of what the world was like before and could become again”. This “fusion of the real and the mythical” is driven “not simply by a need to remember but also by a desire to forget”40. Marc Bloch and the Annales school were arguing along similar lines already in the mid-twentieth century41.

It has been observed in other historical contexts that winning a historical battle tends to reinforce a historical narrative in terms of necessary sacrifice, while the glorification of the dying and of the suffering is presented as noble and heroic. Presenting the history of communism as a long battle won by the anticommunists would accomplish just that. If we reverse the terms of this equation, glorifying the dying and the suffering as noble and heroic would create an impression of victory, and thus would give a sense of historical purpose to the societies that found themselves on the wrong side of the Iron Curtain in 1948. This is why in 2011, as mentioned above, the Czech Parliament passed a law on the so-called third resistance42 (the first resistance being the independence fight against the Austrian empire during the First World War and the second resistance the fight against the Nazi occupant during the Second World War; the third resistance was now supposed to be the fight against the “totalitarian communist regime”).

By recognizing, compensating, and glorifying members of the anticommunist resistance, regardless of its modest size, this law intended to recreate a past that culminated in a palpable victory under the guidance of personified heroes, and thus to make sense of a communist experience that would otherwise be a historical void. Newly minted heroes of the anticommunist resistance are awarded the sum of 100,000 Czech crowns (approximately 4,000 euros, i.e. approximately three months of an average salary or ten months of an average pension). But the construction of this anticommunist heroic identity excluded once again many people from the national narrative: to be precise, 61 % of the applicants43. Like Richard Mariáš, many of these people had been pressured to collaborate with the secret police. In fact, many of them were approached by the secret police precisely because of their actions against the regime.

This latest inflection of memory politics does not serve only to give meaning to Czech history: it increases the institutional standing and influence of its main promoters. We can take as an example one instance of genuine anticommunist resistance that took place in the 1950s, that of the Mašín brothers’. This controversial case illustrates how difficult it is to deal with the communist past. Josef Mašín, the father, had fought in the first and second resistance: he was a legionnaire on the Russian front during the First World War, he fought against the Nazis and bravely withstood torture by the Gestapo before being executed in the Second World War. He is an unimpeachable Czech hero.

His sons, Ctirad and Josef Mašín, took up the fight against the communist regime and were briefly jailed in 1951. In 1953 they decided to escape to the west. In their flight, they killed at least seven people, one of whom apparently in cold blood, a watchman they had kidnapped. The situation further escalated when two members of their group who did not manage to escape were executed, their mother was sentenced to twenty-five years of hard labor and died in custody in 1956, and their sister was also jailed44.

In 2008 and 2011 the two brothers were honored by the offices of the Prime Minister and the Ministry of Defense, although two-thirds of Czech public opinion consider them as criminals rather than heroes worthy of acknowledgement45. Perhaps as a result of this opprobrium, they have not been awarded the status of hero of the anticommunist resistance. But on 28 January 2019 it is their mother, Zdena Mašínová, who was granted this honor. The details of this case point to the relationship between anticommunist activism and state memory politics. Indeed, this honorary notification was issued in memoriam to the Center for the Documentation of the Totalitarian Regimes, which had made the request on Zdena Mašínová’s behalf46.

What is this Center? It was conceived as a shadow office of the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes, although it does not seem to comprise more than a website47 and a Facebook page48. It was created in 2014 by Radek Schovánek and Peter Rendek, two anticommunist activists who had just been fired by the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes. The Center’s deputy director is Petr Blažek, who is still a researcher at the Institute. Its existential aim is to protest against what is in these colleagues’ opinion the forsaking of the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes’ original anticommunist ideals by the current leadership. To come back to Zdena Mašínová, the certificate of anticommunist heroism was issued by Eduard Stehlík, at the time director of the department for war veterans at the Ministry of Defense, who is also chairman of the board of the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes since December 2017.

That the Mašín brothers are not perceived as representative of the vernacular experience of communism does not prevent them from being showcased. Anticommunist history activists can count on judiciously positioned allies in the relevant political institutions, notably the parliament and Ministry of Defense. The main advocates of the Mašíns’ case happen to be history entrepreneurs who have something to gain in terms of political and professional capital. What John Bodnar calls cultural leaders “orchestrate commemorative events to calm anxiety about change or political events…” They are “‘self-conscious purveyors’ of loyalty to larger political structures and existing institutions. Their careers and social positions usually depend upon the survival of the very institutions that are celebrated in commemorative activities”49. Indeed, the same group of anticommunist activists/history entrepreneurs then created the above-mentioned Museum of Twentieth-Century Memory. They are very active in public history: they speak in schools, petition authorities, write open letters, intervene in public debates either as guests or from the floor, and author historical exhibits. For instance, the NGO Post Bellum, whose director is Mikuláš Kroupa, put together to great acclaim an audio-video exhibit of the “horrors of the totalitarian epoch” in the vast basement under the former statue of Stalin in Prague50.

This group of history entrepreneurs hop from institution to institution to create a network of anticommunist activists involved in memory politics. I will mention here four examples: Pavel Žáček, founder and first director of the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes, later advisor at the Ministry of Defense, is an elected member of the lower chamber of parliament for the conservative party ODS since 2017 (after failing to be elected to the Senate in 2014); Eduard Stehlík, the above-mentioned director of the department for war veterans at the Ministry of Defense until the end of 2019, also chairman of the board of the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes since 2017, is the director of the Lidice Memorial since 2020. Mikuláš Kroupa, son of dissident Daniel Kroupa, is a journalist at Czech Radio and author of the popular series Histories of the Twentieth-Century51, director of Post Bellum, co-founder of a major oral history project called Memory of the Nation52 that is jointly coordinated with Post Bellum and the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes, and member of the board of the Museum of Twentieth-Century Memory until he recently resigned after an internal quibble. Petr Blažek is the go-to expert in media articles and TV/radio reports on the communist past. Aside from being a researcher at the Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes and deputy director of the Center for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes, he is also a member of the board of the Museum for Twentieth-Century Memory and was elected by the Senate as one of the nine members of the Ethics Commission of the Czech Republic for Recognition of Participants in Anticommunist Opposition and Resistance. This body evaluates appeals of the decisions concerning the status of hero of the anticommunist resistance taken by the department for war veterans at the Ministry of Defense under the supervision of Eduard Stehlik until the end of 2019.

This institutional network serves the political and professional interests of its protagonists and vice versa. The question is, how representative is it of Czech society as a whole, and of the latter’s attitude concerning the communist past?

History Repeats Itself, But the Second Time It’s a Farce

The function of public memory is to mediate the competing restatements of reality expressed by “antinomies”53. But so far there has been no symbolic language in the Czech Republic that would have the capacity to mediate both the popular loyalty to economic equality (that leaves a place that is not all negative concerning the memory of the communist past) and the official loyalty to a patriotic structure of resistance to communism. To paraphrase John Bodnar, there is no unitary conceptual framework that connects the ideal with the real. As a consequence, there is no social unity or civic loyalty54 in the country – which is characteristic not only of the Czech Republic but of other post-communist countries. Instead of a nationwide memory that can trickle down to particular social groups, which is the classical way in which public memory is formed, the memory of one narrow social group, the self-proclaimed anticommunist activists, is endeavoring to shape the national narrative.

Commemorative activities imposed from the top down “almost always stress the desirability of maintaining the social order and existing institutions, the need to avoid disorder or dramatic changes, and the dominance of citizen duties over citizen rights”55. It is quite symbolic of the deleterious socio-historical situation that the commemorations concerning the communist past have become almost farcical. For the twenty-fifth anniversary of the Velvet Revolution in 2014, President Zeman was pelted with eggs as he was unveiling a plaque. One of the eggs missed its target and hit German President Joachim Gauck instead. Thousands of protesters also brandished red cards (as if demanding his expulsion, in a soccer analogy) to protest Zeman’s defense of Russia in the latter’s feud with Ukraine over Crimea56. In 2018, in the context of wide criticism for alleged corruption and possible involvement with the past secret police, Prime Minister Babiš came to commemorate the Velvet Revolution alone at midnight before going abroad for the rest of the day57 and leaving the street to joyful demonstrators. In 2019, for the thirtieth anniversary of the revolution, neither president Zeman nor himself took part in any public commemoration. Premier Babiš only presided over an indoor celebration for selected guests from Visegrád countries, and he avoided the street58.

In effect, anticommunist history entrepreneurs have a considerable comparative advantage in symbolic politics: repression, trials, camps, suffering, invasions, deaths, dissident actions, demonstrations, or revolutions, are easy to remind and celebrate. The political can be easily represented; the social cannot. This contributed to a distortion in the representation and commemoration of the communist past. The communist ideology and the socialist economy collapsed. The remnants of the communist social welfare are fast disappearing. Free time, solidarity, job certainty, social promotion, the possibility for the working class to study, were positive traits of the communist regime for a large part of the population but they are abstract concepts that are difficult to commemorate in an official ceremony. In consequence, elements that can be fondly remembered have been appropriated not by official memory politics but by vernacular culture: for instance, the Sputnik satellite, the Prague subway, the soft drink Kofola, i.e. symbols of progress, optimism, and a higher standard of living, or at least of a level of comfort. Popular culture has also appropriated the memory of these times: films and TV serials of the communist era are very popular today, including a serial about the communist police59.

As we have seen above, what Veronika Pehe calls the “anticommunist consensus of the cultural elites”60 dominates the political discourse and is largely reflected in the mainstream media, as well as in official memory politics. But she also shows that the scene of popular culture is much more colorful, and the wider public is far from endorsing this black and white vision of the communist past61. An alternative “retro” culture has developed, one that endorses a nostalgic vision of times past if not of the communist regime. According to an opinion poll commissioned by Mikuláš Kroupa’s Memory of the Nation, thirty years after the fall of communism only 36% of the people above forty years of age had a positive opinion of the Velvet Revolution. More than one-third of those above forty thought they “lived better” under communism (for those with minimal education, the level rose to half of them.) They mentioned as advantages under communism: job security, a better welfare state, and more consideration for people within society. Also, only half of all respondents indicated that their standard of living increased after 1989. On the other hand, half of the people under forty would endorse outlawing the Communist Party of Bohemia and Moravia62 – which indicates that the anticommunist narrative does bear fruit within the younger generations.

The country is thus effectively divided between those who promote an anticommunist narrative of what the national assessment of the communist past should be, who occupy a large portion of the public sphere, and a more motley and skeptical wider public. Moral questions have been appropriated only by vernacular culture. The media, in particular Czech popular TV shows, are the only public channels to address the issue of collaboration with the secret police, while historians and politicians are too constrained to do so. To date, there is no Czech historical study of collaboration as a social practice under communism.

On Heroism and Betrayal

Yet this topic would be highly interesting. In 2016, for instance, Czech Television ran a program on informants in its version of the radio series Histories of the Twentieth Century. One episode tells the story of singer Jiří Imlauf, who, together with his friend Petr Mička from the band Houpací koně, happened upon an anti-regime demonstration in Prague in 1988. Someone overheard them discussing the incident at the train station and reported them to the secret police. When they came home to Ustí nad Labem, the police zeroed in only on Imlauf, who was singled out for collaboration while Petr Mička was left alone. The filmmaker reconstructs what Imlauf really did, why he did it, and how both of them dealt with the belated revelation of this collaboration63.

If this film caused little public reaction and no real scandal, the 2014 movie-theater release of another documentary film caused an uproar insofar as it openly questioned the notion of heroism. The film, Pavel Wonka Commits to Cooperate, is about former dissident Pavel Wonka, who has been celebrated as the last political prisoner to have died in police custody in 1988 while on hunger strike64. However, filmmaker Libuše Rudimská reveals that he had also been an informant of the secret police since 1983 and of the criminal police since 1973.

Wonka’s family and the former dissidents who have, according to her “created a cult around him”, did not take this revelation lightly65. After the fall of communism, Wonka was first celebrated as a victim. By the time Rudimská made her film in 2014, he had, in the contemporary spirit, become a symbol of heroic resistance against communism. The filmmaker publicly wondered why historians failed to bring this case to the open and openly disputed the defense of Wonka put up by historian Petr Blažek, who claimed in the media that there was no file of Wonka in the archives even though she says she consulted the file herself66.

American historian Igor Lukes analyzes this case in a sensible way: “Heroes are scarce in modern history. Every hint of civic courage, it seems, needs to be treated with the reverence that was once reserved for holy relics. When evidence appears that casts doubt on a hero’s image, admirers find it difficult to accept. And yet the list of heroic individuals who changed their countries and who – at the same time – betrayed them is not a short one”67. The complex portrait painted by Rudimská represents life in its everyday intricacies, which is not the ideal-type scenario of heroic anticommunism that memory politics are fond of producing.

Was it fair for Richard Mariáš to be denied the status of hero of the anticommunist resistance? No matter the answer, it is a testimony of the times that an individual should feel so disenfranchised by the justice and legal system of their country that they would seek consolation with a historian. Historians are often invested with the symbolical power to take the place of a failing justice system, which is detrimental to both the historical and the judicial professions. That the decision was justified or not, the Czech state failed to communicate any form of reconciliation with Richard Mariáš and many others like him. On this merit alone, the national model of reckoning with the past has been a social failure so far68. Justice was retributive, but it was not restorative69.

The “exclusive notion of national victimhood” described by Christian Axboe Nielsen for the countries of former Yugoslavia70 applies to the rest of East Central Europe. Roman David argues that the link between justice and power, as well as retributive tendencies, are in fact entrenched in Czech political culture71. These traits were doubtless exacerbated by the fact that the countries of this region were historically born late, mostly after the First World War. They were not homogeneous, indeed they saw the competition of several nations within the same state. The late development of the nation-state collided with the reality of an imperial and post-imperial mixture of nationalities without clear borders, which led to several disastrous developments in the twentieth century: the First and Second World Wars, as well as afferent postwar ethnic cleansings and the (post-)Yugoslav wars.

This structural identity crisis in the region is now meeting with another identity crisis, one that struck all of the Western world at the beginning of the twenty-first century. In a volume whose title is self-explanatory, Identity: The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment, Francis Fukuyama notes that identity politics have become a common manifestation of our times. If the “inner self” is the basis of human dignity, “Identity grows … out of a distinction between one’s true inner self and an outer world of social rules and norms that does not adequately recognize that inner self’s worth or dignity … It is not enough that I have a sense of my own worth if other people do not publicly acknowledge it or, worse yet, if they denigrate me or don’t acknowledge my existence. Self-esteem arises out of esteem by others”72.

The modern sense of identity has thus evolved into identity politics in which people “demand public recognition of their worth”, concludes Fukuyama73. This is how the late developer that was East Central Europe is finding itself at the forefront of world identity politics in the twenty-first century. Economic grievances and an identity crisis followed the fall of communism; moreover, the current situation is a natural consequence of having already experienced forty years of populism, which is, in essence, the kind of regime that communism was. The combination between an exclusivist notion of suffering and the contemporary demand for the recognition of one’s identity has led to an explosive combination: a demand for dignity mixed with a politics of resentment. One of its avatars is the recent attempt at the European Union level to have communist repression equated with the Holocaust74.

Paraphrasing Julia Creet in her analysis of the Hungarian House of Terror, the aestheticization of historical victimization is attempting to provoke resentment and melancholia in Czech citizens as a means of staging moral values and perpetuating contested memories75. This process has little to do with history, and much to do with political and institutional power.

What was accomplished in the name of justice not only led to no reconciliation, it also brought little justice. Instead, it reinforced in many people the feeling of being isolated victims in need of redress and prone to resentment. When the pursuit of justice is accentuated at the expense of reconciliation, a society “risks pursuing reparation without closure, shaming without reintegration, and punishment without changing the offenders’ behavior. Without reconciliation, transitional justice is just a power game with new actors in the same role of exclusion”, concludes Roman David76. This is no less than a mirror of past practices.

The solution is obvious: reconciliation is not an alternative to justice but its prerequisite77. As long as there is no reconciliation, there will be no closure and no national narrative on communism in which every citizen can feel included.

Notes

1

Many thanks to Valentin Behr, Ewa Tartakowsky, Raluca Grosescu, Veronika Pehe, Jill Massino, Marián Lóži, Michal Louč, Gérard-Daniel Cohen, and Pavel Marc for their critical remarks on this text. I would also like to thank Ivan Vejvoda and the Institut für die Wissenschaften vom Menschen for an EURIAS Senior Fellowship spent at IWM in 2018-2019, which partly funded this research. Last but not least I would like to thank Richard Mariáš for sharing his story with me.

2

See “Dvojitý agent StB a FBI”, Dnes Prague Edition, 23 October 2012 [online].

3

See Act 262/2011 On the Participants in Anti-Communist Opposition and Resistance [online]. The law is phrased in emotional terms, for instance by “voicing its profound sorrow over the innocent victims of the communist regime’s terror.”

4

The law states in Section 4, (1), b): “A citizen is not recognized as a participant in anti-communist opposition and resistance if he or she, during the time of non-freedom … was on record in the documents of security forces as their collaborator or secret collaborator, and/or was a member of the Assistant Guards of the Police, an assistant of the Border Guards, or an informer to the intelligence apparatus of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia, and/or otherwise collaborated with the security forces or the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia in a similar manner …” Act 262/2011 On the Participants in Anti-Communist Opposition and Resistance [online].

5

John Bodnar, The “Good War” in American Memory, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010, p. 2.

6

John Bodnar, The “Good War” in American Memory, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010, p. 3.

7

John Bodnar, The “Good War” in American Memory, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010, p. 3.

8

Originally published in the lowbrow periodical Rudá krávo, they can now be found online.

9

Josef Škvorecký, Two Murders in My Double Life, New York, Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2001 (1996).

10

Zdena Salivarová put together an anthology of people who, like her, felt they had been unjustly accused and/or victimized by the post-communist regime: Zdena Salivarová (ed), Osočení, antologie příspěvků lidí nespravedlivě osočených ze spolupráce s StB, Toronto, ’68 Publishers, 1993.

11

Historian Petr Blažek, for instance, has publicly proffered accusations of collaboration or his indignation at hearing a former communist official speak in public. See, for an example from 2007 Muriel Blaive, Nicolas Maslowski, “Domination and Power Mechanisms of the Czechoslovak Communist Party at the Philosophical Faculty, Charles University, 1968-1989”, H-Soz-Kult, 9 January 2008 [online] ; and for an example from 2018, Jakub Vosáhlo, “Šokující výstup Marka Wollnera na akci s generálem Alojzem Lorencem. A výbušné informace, které padly”, Parlamentní listy, 23 November 2018 [online].

12

Jiří Přibaň, “Oppressors and their Victims: The Czech Lustration Law and the Rule of Law”, in Alexander Mayer-Rieckh, Pablo de Greiff (eds), Justice as Prevention. Vetting Public Employees in Transitional Societies, New York, Social Science Research Council, p. 309.

13

Roman David, “Transitional Justice Effects in the Czech Republic”, in Lavinia Stan, Nadya Nedelsky, Post-Communist Transitional Justice. Lessons from Twenty-Five Years of Experience, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 101.

14

Roman David, “Transitional Justice Effects in the Czech Republic”, in Lavinia Stan, Nadya Nedelsky, Post-Communist Transitional Justice. Lessons from Twenty-Five Years of Experience, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 101.

15

Roman David, “Transitional Justice Effects in the Czech Republic”, in Lavinia Stan, Nadya Nedelsky, Post-Communist Transitional Justice. Lessons from Twenty-Five Years of Experience, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 101.

16

Roman David, “Transitional Justice Effects in the Czech Republic”, in Lavinia Stan, Nadya Nedelsky, Post-Communist Transitional Justice. Lessons from Twenty-Five Years of Experience, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 115.

17

Roman David, “Transitional Justice Effects in the Czech Republic”, in Lavinia Stan, Nadya Nedelsky, Post-Communist Transitional Justice. Lessons from Twenty-Five Years of Experience, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 105.

18

Czech Republic Constitutional Court Judgement, Pl.ÚS 3/14 of 20 December 2016, Access to Archival Records of the Former Security Services and Protection of Personal Data [online].

19

Czech Republic Constitutional Court Judgement, Pl.ÚS 3/14 of 20 December 2016, Access to Archival Records of the Former Security Services and Protection of Personal Data [online].

20

Veronika Pehe, Velvet Retro. Postsocialist Nostalgia and the Politics of Heroism in Czech Popular Culture, Oxford, Berghahn, 2020, p. 156.

21

Act No. 198/1993 Coll on the Illegality of the Communist Regime and on the Resistance Against It, 30 July 1993 [online]. This act of Parliament is considered by jurists as a proclamative act of the new regime rather than as a piece of legislation. It lacks the constituent part of any norm but is a value judgment that can be relevant in the application of other laws that contain true norms.

22

1993/12/21 - Pl. ÚS 19/93: Lawlessness. Headnotes, “Czech Republic Constitutional Court judgment concerning the petition submitted by a group of Deputies to the Parliament of the Czech Republic seeking the annulment of Act No. 198/1993 Coll, regarding the Lawlessness of the Communist Regime and Resistance to It” [online].

23

Petr Uhl, Právo a nespravedlnost očima Petra Uhla, Prague, C.H. Beck, 1998, p. 156.

24

“In the vastly different political landscape of Europe’s post-communist states, the left is either very weak or completely absent from the political mainstream. … As a result, Eastern Europe is much more prone to the ‘friend or foe’ dichotomy ... Each side conceives of itself as the only real representative of the nation, and treats its opponents as illegitimate alternatives, who should be disenfranchised, not merely defeated.” Sławomir Sierakowski, “How Eastern European Populism is Different”, Political Critique, 14 February 2018 [online].

25

Kristen Ghodsee, “A Tale of ‘Two Totalitarianisms’: The Crisis of Capitalism and the Historical Memory of Communism”, History of the Present, Vol. 4, No. 2, Fall 2014, p. 117.

26

Nadya Nedelsky, “Czechoslovakia, and the Czech and Slovak Republics”, in Lavinia Stan (ed), Transitional Justice in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union. Reckoning with the Communist Past, London, Routledge, 2009, p. 44.

27

See kož, “Cibulka vyškrtl svou matku ze seznamů StB”, Týden.cz, 26 January 2011 [online].

28

“According to Pavel Brunnhofer, Assistant Director of the Ministry of Interior Archives, a major reason for the high verdict turnover rate is that the courts accept only original paper evidence, not records transferred to microfiche (which was done with much StB documentation) as signatures cannot then be verified. Because many paper records were destroyed or have gone missing, and because the Ministry of Interior has the burden of proof, this rule works overwhelmingly to the advantage of those challenging verdicts.” See Nadya Nedelsky, “Czechoslovakia, and the Czech and Slovak Republics”, in Lavinia Stan (ed), Transitional Justice in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union. Reckoning with the Communist Past, London, Routledge, 2009, p. 49-50.

29

Nadya Nedelsky, “Czechoslovakia, and the Czech and Slovak Republics”, in Lavinia Stan (ed), Transitional Justice in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union. Reckoning with the Communist Past, London, Routledge, 2009, p. 45.

30

Nadya Nedelsky, “Czechoslovakia, and the Czech and Slovak Republics”, in Lavinia Stan (ed), Transitional Justice in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union. Reckoning with the Communist Past, London, Routledge, 2009, p. 53.

31

Marci Shore, “‘A Spectre is Haunting Europe…’ Dissidents, Intellectuals and a New Generation”, in Vladimir Tismaneanu, Bogdan C. Iacob (eds), The End and the Beginning. The Revolutions of 1989 and the Resurgence of History, Budapest, CEU Press, 2012, p. 467.

32

See Erik Tabary, “Disident s StB”, Respekt, 7 July 1999, p. 5.

34

Even in occupied postwar Germany, it proved impossible for the Western allies to denazify the judges’ corps as much as it deserved to be. In the English and American zones of occupation, it is estimated that approximately 70 % of the judges had served under Nazism. See Devin O. Pendas, “Retroactive law and proactive justice : debating crimes against humanity in Germany, 1945-1950”, Central European History, vol. 43, no 3, 2010, p. 434.

35

Julian Barnes, The Porcupine, London, Vintage, 2014 (1992), p. 33.

36

After the crushing of the 17 June 1953 workers’ uprising in East Berlin, Berthold Brecht wrote a poem entitled The Solution: “After the uprising of the 17th June / The Secretary of the Writers Union / Had leaflets distributed in the Stalinallee / Stating that the people / Had forfeited the confidence of the government / And could win it back only / By redoubled efforts. Would it not be easier / In that case for the government / To dissolve the people / And elect another?” See online.

37

Gary Bruce, “East Germany”, in Lavinia Stan (ed), Transitional Justice in Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union. Reckoning with the Communist Past, London, Routledge, 2009, p. 23.

38

Gary Bruce, The Firm. The Inside Story of the Stasi, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 2.

39

John Bodnar, The “Good War” in American Memory, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010, p. 3.

40

John Bodnar, The “Good War” in American Memory, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins University Press, 2010, p. 3.

41

See Marc Bloch, The Historian’s Craft, New York, Vintage, 1953, p. 35-47.

42

Act 262/2011 On the Participants in Anti-Communist Opposition and Resistance [online].

43

According to the statistics presented by the Ministry of Defense, by 27 February 2015 832 certificates of participation to the third resistance had been issued, while 1,313 requests had been denied, i.e. 61 % of the total. See online.

44

For a deconstruction of the “Mašín myth”, see Josef Švéda, Mašínovský mýtus, Prague, Pistorius, 2012.

45

See Monika Kuncová, “Bratři Mašínové – odbojáři, nebo vrazi?”, Právo, 29 September 2019 [online]. According to Wikipedia, Zdena Salivarová’s ‘68 Publishers refused to publish Ota Ramboušek’s novelized account of the Mašíns’ adventures: online. It is to be noted that the homicides that accompanied their anti-communist activity are not subject to indictment; indeed, the rehabilitation law of 1990 provides that sentences passed by the previous regime can be annulled “if it is proved during the proceedings that the conduct of the convicted person was aimed at protecting fundamental human and civil rights and freedoms by means that are not clearly disproportionate.” 1993/12/21 - Pl. ÚS 19/93: Lawlessness. Headnotes, “Czech Republic Constitutional Court judgment concerning the petition submitted by a group of Deputies to the Parliament of the Czech Republic seeking the annulment of Act No. 198/1993 Coll, regarding the Lawlessness of the Communist Regime and Resistance to It.”

46

See “Paní Zdenka Mašínová byla ministerstvem obrany oceněna in memoriam jako účastnice protikomunistického odboje”, Centrum pro dokumentaci totalitních režimů [online].

49

John Bodnar, Remaking America. Public Memory, Commemoration, and Patriotism in the Twentieth Century, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1992, p. 15.

50

See for instance ČTK, “Stalinův pomník ožil. Audiovizuální výstava ukazuje hrůzy totalitních období”, Pražský deník, 1 October 2018 [online].

51

Příběhy 20. století, see online.

52

Paměť národa, see online.

53

John Bodnar, Remaking America. Public Memory, Commemoration, and Patriotism in the Twentieth Century, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1992, p. 14.

54

John Bodnar, Remaking America. Public Memory, Commemoration, and Patriotism in the Twentieth Century, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1992, p. 16.

55

John Bodnar, Remaking America. Public Memory, Commemoration, and Patriotism in the Twentieth Century, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1992, p. 19.

56

Philip Oltermann, “Czechs Pelt Their President with Eggs at Velvet Revolution Anniversary”, The Guardian, 17 November 2014 [online].

57

See the video “17. listopad” that he posted on his Facebook page: online.

58

See “Prime Minister Babiš celebrates 30th anniversary of November Revolution with V4 colleagues, and calls in his speech for discussions free from anger”, 17 November 2019, Government of the Czech Republic [online].

59

On the role played by these serials to stabilize the normalization regime see Paulina Bren, The Greengrocer and His TV, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 2010.

60

Veronika Pehe, Velvet Retro. Postsocialist Nostalgia and the Politics of Heroism in Czech Popular Culture, Oxford, Berghahn, 2020, p. 32.

61

The failure to identify with normative categories “made in Prague” and the moral impossibility to judge the behavior of most people was driven particularly clearly to me by my oral history interviewees in the small town of České Velenice, see Muriel Blaive, “České Velenice, eine Stadt an der Grenze zu Österreich”, in Muriel Blaive, Berthold Molden, Grenzfälle. Österreichische und tschechische Erfahrungen am Eisernen Vorhang, Weitra, Bibliothek der Provinz, 2010, p. 137-271.

62

See “Sametovou revoluci hodnotí kladně 36 procent lidí. Starší ročníky vzpomínají na komunisty”, Parlamentní listy, 22 October 2019 [online].

63

Viktor Portel, “Agent Vian”, CT2, 3 September 2017 [online].

65

Štěpánka Ištvánková, “Against the Grain. Interview with Libuše Rudimská, Director of Pavel Wonka Commits to Cooperate (Pavel Wonka se zavazuje)”, Dok Revue, 29 December 2014 [online].

66

Libuše Rudimská, “Wonka vědomě spolupracoval s StB, říká autorka dokumentu”, Interview with Daniela Drtinová, DVTV, 23 October 2014 [online].

67

Igor Lukes, “Tarnished Heroes: Don’t Dismiss Them”, The Conversation, 31 December 2014 [online].

68

The Czech case is certainly not the only one, insofar as it has been a general trend in post-communist countries to see politics interfere in the working of justice. See for instance Raluca Grosescu, Raluca Ursachi, “Transitional Trials in History Writing. The Case of the Romanian December 1989 Events”, in Agata Filjalkowski, Raluca Grosescu (eds), Transitional Criminal Justice in Post-Dictatorial and Post-Conflict Societies, Cambridge, Intersentia, 2015, p. 69-100.

69

See Orhun Hakan Yalincak, “The Case for Restorative Justice in the Context of Crimes Against Humanity” [online].

70

Christian Axboe Nielsen, “Collective and Competitive Victimhood as Identity in the Former Yugoslavia”, in Nanci Adler (ed), The Age of Transitional Justice. Crimes, Courts, Commissions, and Chronicling, New Brunswick, Rutgers University Press, 2018, p. 177.

71

Roman David, “Transitional Justice Effects in the Czech Republic”, in Lavinia Stan, Nadya Nedelsky, Post-Communist Transitional Justice. Lessons from Twenty-Five Years of Experience, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 101-102.

72

Francis Fukuyama, The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018, p. 9-10.

73

Francis Fukuyama, The Demand for Dignity and the Politics of Resentment, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2018, p. 10.

74

See Laure Neumayer, The Criminalisation of Communism in the European Political Space after the Cold War, London, Routledge, 2018.

75

Julia Creet, “The House of Terror and the Holocaust Memorial Centre: Resentment and Melancholia in Post-89 Hungary”, in Conny Mithander, John Sundholm, Adrian Velicu (eds), European Cultural Memory Post-89, European Studies, 30, 2013, p. 29-62.

76

Roman David, “Transitional Justice Effects in the Czech Republic”, in Lavinia Stan, Nadya Nedelsky, Post-Communist Transitional Justice. Lessons from Twenty-Five Years of Experience, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 114.

77

Roman David, “Transitional Justice Effects in the Czech Republic”, in Lavinia Stan, Nadya Nedelsky, Post-Communist Transitional Justice. Lessons from Twenty-Five Years of Experience, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 116.