In those countries, which were to be subsumed under the notion of “Eastern Europe”, trials against high profile war criminals or warmongers formed a deliberately visible part of the iceberg of purges that followed the Second World War. These trials shared a common feature: for a combination of domestic and international reasons, they were granted exceptional visibility by the then governing elites. Thereby, the trials transcended the national borders of the states where they were held. Nevertheless, the judgement of war criminals was not confined to the immediate post-war years. In several Central and Eastern European countries, a new wave of public trials started in the late 1950s. While the context differed substantially from the post war years, the resort to justice served once again a mix of domestic and diplomatic purposes. Scholarship on postwar trials has significantly expanded over the past decades. Central and Eastern European case studies, however, remain less often investigated.The purpose of the present panel is to throw a comparative look on several postwar trials, which took place in both Western and Eastern Europe, and to map political, social and symbolic commonalities between cases that were long studied in isolation. Particular attention will be devoted to the East-West/west-East transfers in legal models, normative frameworks, as well as in ways of getting justice done. In expanding the geographic and the chronological scopes, the panel will contribute to the writing of an (all) European history of the trials of Nazi criminals.

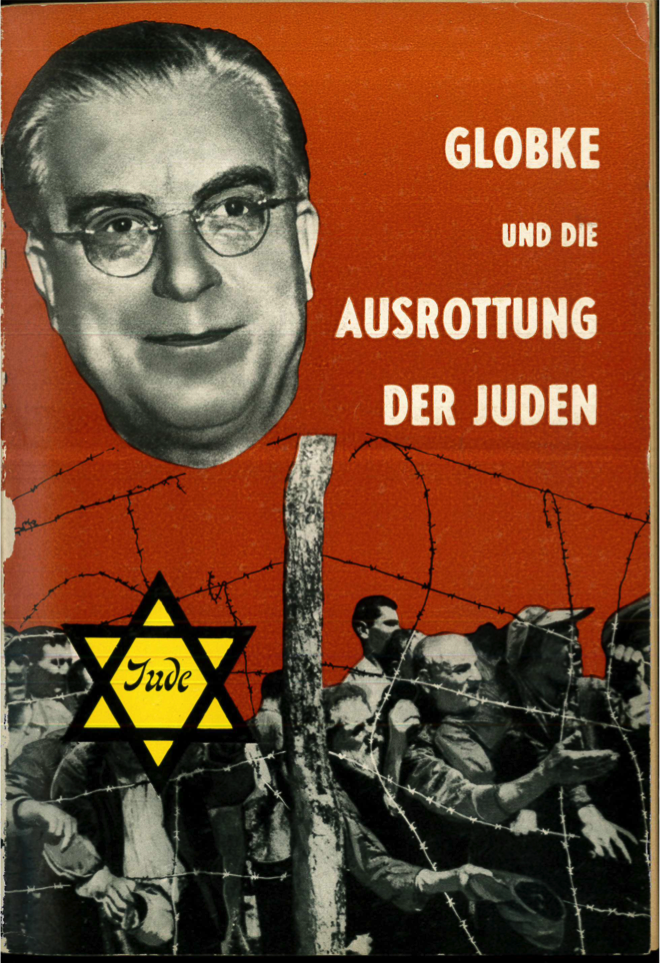

The covers of brochures West and East Germans on the affair Hans Globke.

Nadège Ragaru, Soliloquies in the Courtroom: The Prosecution of Anti-Jewish Crimes in Bulgaria and the Fashioning of an Antifascist Master Narrative of the War (1944-1945).

In December 1944, a Chamber, which was solely dedicated to the prosecution of anti-Jewish crimes during World War II, was established within the Bulgarian People’s Court. Bulgaria was thus amongst the first states in Europe to hold trials with an exclusive focus on anti-Jewish persecutions. A key experiment in the qualification of crimes, the definition of evidence and the establishment of proof, the Bulgarian trials were not insulated from the wider political and social conflicts associated with the ascent to power of the Fatherland Front, the purges in the state apparatus, and the slow abolishment of anti-Jewish measures. Within the framework of the present communication, the trials for anti-Jewish crimes will thus be considered as a stage on which several contenders – the prosecutors, the judges, the lawyers, and the witnesses – fought over the reading of the recent past and the present in the making. Seen from this perspective, the Court offers a lens on the complex renegotiations of the relations between Jews and non-Jews, as well as between communists and Zionists at the end of the war. Ultimately, the speeches of the prosecutors and the judgement of the Court took part in the fashioning of an anti-fascist master narrative about the war that tended to downplay the specificity of the Jewish experiences of the war and that was to exert an enduring influence over the public discourse on the Holocaust in Bulgaria.

The article of East German newspaper on the Soviet movie The Victims accuse, January 31st, 1963.

Fabien Théofilakis: The Eichmann Trial (1961) seen from a West and East German perspective: Where are the culprits?

In May 1960, Prime Minister Ben-Gurion announced in Parliament that the “architect of the Final Solution of the Jewish Question”, the former SS officer Adolf Eichmann, had been kidnapped to be tried in Israel. In both German States which still did not have any diplomatic relationships with another, such breaking news changed the German-German rivalry in their pretention to represent the legal Germany and became quickly a new argument to accuse the other state to be the successor of the National-Socialist regime: on the one hand, Federal chancellor Adenauer agreed with Ben-Gurion to avoid any allusions to the German Federal Republic during the trial; on the other hand, the German Democratic Republic sent its lawyer, doctor Karl Kaul, to join a civil action to the proceedings in order to denounce Nazis at work in Bonn republic. But the greatest fight took place in the media, especially in the press, to win the battle for public opinion of the other Germany. From the study of West and East German press (Die Süddeutsche Zeitung, Die Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung; Das Neue Deutschland), the contribution will compare the treatment of the Eichmann trial in both countries and focus on four key moments of the trial: the opening sessions with the reading of the indictment; the perception of the defence strategy of Eichmann; the production of evidences under form of documents or testimonies; the verdict and the lessons learnt from the trial. What does such an analysis reveal on the legacies of WWII in post-Germany?

The photography accompanying the article of V. Mikhailov, “The butchers and their defenders. The American imperialists cover the war criminals”, Sovetskaja Belorussija.

Vanessa Voisin, Alexander Friedman: ‘The Victims Accuse’: Domestic and International Dimensions of the Soviet Campaign against the Koblenz Trial Approach, (1963)

After fifteen years of oblivion, the Soviet authorities came back to the theme of war suffering and war crimes. This unexpected move was fostered by the Eichmann trial, first considered with careful attention, then denounced as a mascarade designed to cover up many unpunished criminals. From this moment on, Moscow launched systematic attacks against the West, presented as traitor to its Nuremberg pledges and protector of former Nazi criminals. The national, republican and local press raged about prominent figures in the West German society and government. Meanwhile, Moscow resumed the postwar practice of public trials, henceforward targeting local collaborators indicted with war crimes (karateli). The Soviet reaction to the Koblenz trial (1963-1965), prosecuting crimes committed in Belorussia, is part of a larger campaign of claiming the legacy of postwar international law against an oblivious West. Broad in scope and sometimes bold in details, the campaign used written as well as visual medias, going exceptionally far in its description of war crimes, notably the Holocaust. The paper will give some insights into the circulation of the campaign and its impact on Western audience. It will also explore the repercussions of the campain on the Soviet narrative of the war.