What is a border? Social science literature abounds with increasingly metaphorical uses of “border” and dividing lines between social groups, racialized groups, etc. Some even call for “critical border studies” divested of the “omnipresent territorial epistemology”.1 Studies of national borders and their contemporary developments (the return of national borders, their “thickening” and mobility, the fact that they are no longer lines but “borderized” places, etc.)2 tend to focus on a single aspect thereof: control over the cross-border movement of persons – which is obviously linked to current events and the migration crisis in the EU since the mid-2010s. This crisis has significantly reoriented academic research, which, since the 1990s, was previously centered on the fluidity of cross-border movement and on informal trade networks and transnational families.3

The southernmost section of the Alpine border between Italy and France cuts across the Roya Valley, which, as a result, has become a flashpoint in the migration crisis. Like Calais and Lampedusa before it, Ventimiglia (French: Vintimille), an Italian town located at the mouth of the Roya River, has become a symbol of the (mostly illegal) practices restricting freedom of movement for certain categories of foreigners within the EU.4 The establishment of a checkpoint on the mountain road connecting the middle Roya Valley to the rest of France in 2015 again raises questions about the coherency of this border in contemporary Europe.

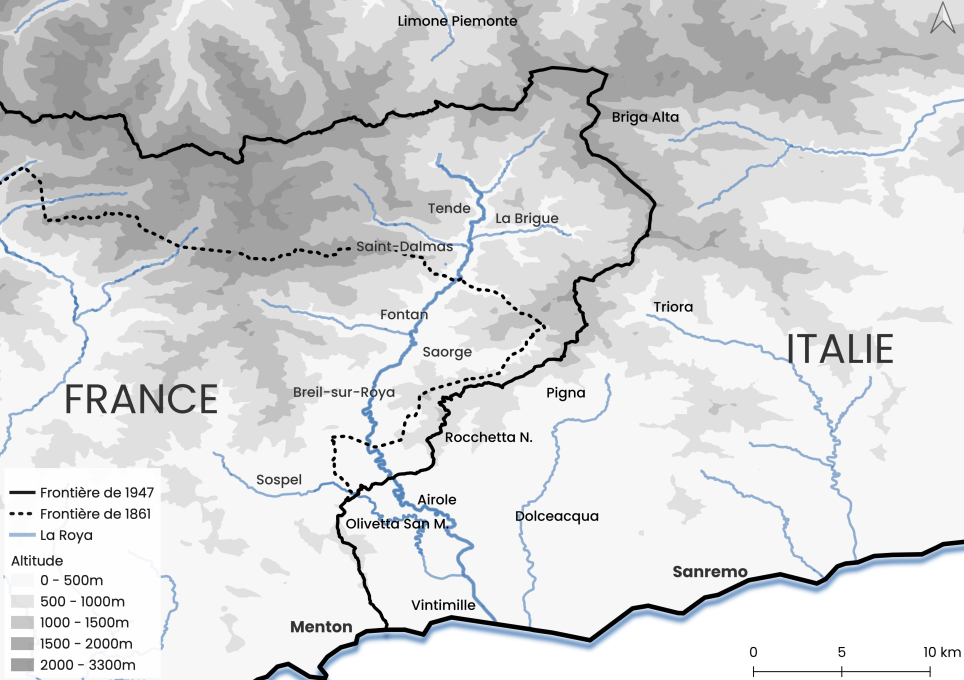

Map 1. Location of Roya Valley.

But controlling the movement of people is only one strand of the skein of boundary lines at the border. The point of a border is to line up a wide array of limits on human activity, not just human mobility. While the movement of persons is now filtered elsewhere (at train stations, airports, detention centers, etc.), this does not necessarily apply to other aspects involved in the exercise of national sovereignty. This case study of the Roya Valley serves to unravel this tangle of boundaries at the border and trace its development over time, as well as to identify the multiple components of a state border.5

A bundle of boundaries, a skein of tangled lines

The point is to enter into the “thick of the border”6 in two dimensions: vertically, by identifying the various boundary lines that are by now (almost) perfectly superimposed and consequently indistinguishable when viewed “from above”; and horizontally, by tracking the process through which the dividing lines with respect to different kinds of activity (trade, language usage, etc.) have come to be aligned with the state border. The present analysis of the border as a skein of boundaries makes use of a dual perspective: historical and geographic.

“Without gaps or overlaps”

This alignment of boundaries is historically and geographically unique to nation-states.7 It was established in France over the course of the 18th century. Prior to that, one and the same place would be subject to various authorities depending on the sphere of activity concerned: dioceses, seigneurial and feudal rights, baillages (bailiwicks) and sénéchaussées (seneschalties) for royal justice, governors of military districts, généralités (generalities) with their intendants, and the like. Pierre Rosanvallon argues that the modern alignment of boundaries began with the French Revolution and its establishment of the département as the sole administrative division in 1790.8 Other historians follow its effects over time: Léonard Dauphant describes the gradual solidification of the Meuse border in the 16th century as a “faisceau de limites” or “bundle of boundaries”.9 Daniel Nordman traces the historical development of linear borders, as the boundaries delimiting various kinds of activity coalesced into a single line. In the second half of the 18th century, he writes, “Heterogeneous and superimposed rights, complex and conflicting connections between places gave way to physically homogeneous units placed side by side, which reconfigured all the borders and the entire kingdom without any gaps or overlaps.”10

“Layered sovereignty”

The coexistence of different sovereignty regimes is crucial to Jane Burbank and Frederick Cooper’s analysis of empires11. The key characteristic of imperial formations, they observe, is the ability to govern in a differentiated manner, without seeking to superimpose a people, an area and a single political authority. They describe these institutional and political practices as “overlapping, layered sovereignty”, which incorporates existing political units into an empire and connects and hierarchizes them within it. Here again, in the case of mainland France and Italy, the authors point out that colonial states allow for this coexistence of differentiated legal and political systems within a single political unit: the various forms of layering that go to make up state sovereignty do not cease to exist just because they have been aligned along the same perimeter.

Paradoxically “powerful and incoherent”

In this dual perspective, I view the border as a bundle of more or less restrictive boundaries imposed on or applied to the many ordinary practices that go to make up the social life of an area. The multiple lines composing a border continue to exist even if their superimposition obscures their multiplicity. My historical ethnography of the Upper Roya Valley points up this tangled skein of boundaries, which is actually present at every border. This particular border did not solidify until fairly late (1920s-1930s), but it became very dense immediately after it was redrawn for the last time in 1947, during which two villages and a few valleys were transferred from Italy to France, and then again in 2015 with the reintroduction of border controls inside the EU that had been removed in 1997.

This exceptional case of a border drawn and then moved, opened and then closed again, reveals its various component layers and the several actors involved in maintaining its various lines and their relative superposition. It shows that the actions of rulers and ruled do not always concern the whole skein of boundaries but, at any given moment, one or other of its strands. As a result, this unusual case provides a window on the ordinary practices that go to make up this paradox: “The paradox that what we call the state is at once an incoherent, multifaceted ensemble of power relations and a vehicle of massive domination.”12

The border as a window on ordinary statism

Studying a border is a way of studying the state as well as the presence of the state, and political institutions in general, in our lives. Examining the processes through which a national border solidifies for the communities that use it shows that these processes have less to do with their internalizing a sense of national and symbolic belonging than with their concrete relationships to state institutions.

Belonging to the state or the nation?

Since the late 1990s, various studies have employed the term “banal nationalism” to describe a sense of “national belonging” that is omnipresent and “taken for granted” in our day.13 This perspective makes “national belonging” particularly difficult to grasp empirically, unless we see it everywhere – at least in “settled times” of firmly established nationalism. On the other hand, exceptional circumstances and times of crisis, as well as a nation’s margins, its borders, can prove revealing insofar as the borders become places where the work of establishing and consolidating the nation and state becomes visible. Peter Sahlins studies villages in a Pyrenean valley once traversed by the Franco-Spanish border in the 17th and 18th centuries in order to understand the relationships to national identity that are formed there. He finds that national identity is formed not so much by diffusion from a nation’s center as by local appropriation, which is initially of an instrumental nature, but ends up making sense to the inhabitants.14

Although my approach is close to Sahlins’ historical ethnography of village communities, even if we study different periods in history, my findings differ: the Roya Valley communities have consistently maintained a highly instrumental relationship – and more to the state than to the nation. However, the idea that extraordinary circumstances can bring banal nationalism to light was what first sparked my interest in the 1947 redrawing of the French-Italian border in the Southern Alps. On the face of it, judging from contemporary discourse, this border shift seemed to be driven by nationalist claims: the boundary was redrawn because local communities wanted to become French and expressed this desire in a vote. But in the archives and contemporary interviews, I soon found that locals seldom advanced nationalist arguments, adducing instead, for the most part, socioeconomic motives. Nationalism is not just a political project or ideology, it is also a category of perception and action. It is a belief now taken for granted that “the world is (and should be) divided into identifiable nations, that each person should belong to a nation, that an individual’s nationality has some influence on how they think and behave and also leads to some responsibilities and entitlements”.15 My study eschews this essentialist notion that a person’s nationality corresponds to certain behaviors.

Map 2. Shifting borders in the Roya Valley.

In the Romanian town studied by Brubaker et al.,16 despite the relative rarity of expressions of nationalist political sentiment, “Romanians” and “Hungarians” are nonetheless widely used categories in everyday life there. In the mountain villages I study, the population is not divided up into “Italians” and “French”. The terms may be used to refer to governments and political institutions, but conflicts within the local population are formulated in terms of political choices (“Italophiles” versus “Francophiles”, i.e. attached to Italian or French institutions) and not in substantive terms. At no point is it suggested that there might be an essential difference between inhabitants of the same village or valley. It might seem self-evident that communities with the same living conditions and with neighborly ties do not consider themselves different from one another, but other social and historical circumstances have shown, on the contrary, that this distinction can be taken to extremes. The genocide of the Tutsis in Rwanda, for instance, was carried out by their neighbors.17

Thus, my inquiry led me away from an official backward-looking view of the redrawing of the border, in which nationalism figures foremost, and towards a reversed reasoning instead. This involved first ascertaining the socioeconomic characteristics of these Alpine communities and the effects thereof on their political relationships, which would shed light on the ways in which local sentiment is mobilized according to the villages’ sense of national belonging. This would also explain why setting themselves apart from the “Italians” is not essential: what matters is free movement between the Upper Roya Valley and the French coast – Nice, Cannes, Monte Carlo.

Moving the border to preserve mobility

These mountain villages engage in movable farming and grazing, an approach adapted to the small proportion of arable land: livestock, harvesting, logging and crop growing move with the seasons. Furthermore, a sizeable number of the peasants in the upper valley go to the nearby coast to work during the winter. This seasonal mobility is typical of mountain villages. What is peculiar to the Roya Valley, however, is that, instead of following the Roya River to Ventimiglia, these migratory flows veer westwards to Nice. There are two reasons for this: one being the quasi-continuous political fragmentation of the valley down through the centuries, which has shaped the various successive salt roads across it. These roads connected Nice to Turin, both of which belonged to the Savoyard state, and they all circumvented the lower valley, which belonged to the Republic of Genoa until the end of the 18th century. The development of winter tourism on the Côte d’Azur in the second half of the 19th century accentuated this phenomenon by creating demand for service staff (hotel, restaurant and domestic workers) in the winter, precisely the period of inactivity for mountain communities. Even though the County of Nice was ceded by Piedmont-Sardinia (formerly the Savoyard state) to France in 1860, having to cross a national border had little impact on this seasonal migration, at least until the 1920s and 1930s, when the Fascist regime as well as the French government introduced policies restricting cross-border movement.

After World War II, the first to call for the border to be redrawn beyond the Upper Roya were valley-dwellers employed in the luxury hotel industry or as shopkeepers on the Côte d’Azur. They were transnationals who wished to divest themselves of that status: although they had jobs on the coast, they wanted to be able to return regularly to their village, to own property and hold elected office there, etc. Given the scale of these more or less temporary mobility phenomena, their demand resonated with other inhabitants of the Roya, with natives and emigrants alike. It was taken up by civic leaders in Nice, who passed it on to the Gaullists. De Gaulle made it the paramount symbol of his victory over Italy. From the spring of 1945 to that of 1946, this tiny territorial claim became such a sticking point in Franco-Italian diplomatic relations and in the peace conference with Italy, as well as on the ground, that Allied troops actually threatened to attack the French to stop their occupation of the contested area.

Grasping the makeup of state sovereignty

My approach is, in a sense, close to that of Daniel Nordman, who chose to analyze the history of the border in the 18th century without resorting to the concept of “nation”, but to use that history to study the “connections between the State, which establishes borders, and the space that forms the material in which borders are imprinted”.18 While Nordman’s work has provided me with an invaluable point of reference, he is interested in the inhabitants’ demands only insofar as they concern the border line itself. Similarly, my work seeks to understand in particular the movement that led to the redrawing of the border in 1947, but gives broader consideration to the local inhabitants, practices and institutions that go to make up the area traversed by the border. In other words, I study the border skein at two different levels of focus: the first zeroes in on the boundary itself in order to distinguish the various lines superimposed there, while the second widens its focus to explore the effects of this alignment on various kinds of activity with varying perimeters.

The object is not merely to observe the constant, daily (albeit invisible) “work of the state”, which maintains the border as a “dividing line and not as a site of interaction and connection”,19 but also the state’s efforts to shore up the local communities’ sense of belonging to the state and the nation. Sovereignty is, after all, as much about the populace as it is about sovereign territory. This case study serves to explore the specific makeup of state sovereignty. What does it consist of? What are the various practices that combine to make it tangible at local level? Above and beyond imagery and symbols, sovereignty is the product of multiple negotiations between the institutions of the two neighboring states, as well as between these institutions and the citizens concerned – the point being to shed light on “banal statism” rather than “banal nationalism”. Anthropologists Veena Das and Deborah Poole suggest that the “forms of illegibility, partial belonging, and disorder that seem to inhabit the margins of the state constitute its necessary condition as a theoretical and political object”, and that these “contested, fragmented, weakly sovereign borders represent less of an ‘exceptional’ place of subversion than a useful site from which to critique the seeming ‘naturalness’ of state territoriality elsewhere”.20

This border situation puts citizens in a position to experience, and perhaps compare, two kinds of treatment by the state. It provides an original vantage point for an exploration of what changes when you change states – temporarily (by crossing the border) or permanently (when the border is redrawn) – and, consequently, what it means to “belong” to a state. The situation in the Upper Roya Valley in 1947 was, in this view, a sort of experiment: these villages and villagers changed states without anything else changing – the villages were still in the same place, their inhabitants remained the same people. In other words, unlike migrants, they were in a situation of what might be called “pure” state resocialization.

A historical ethnography

Beyond recounting its exceptional history, a case study of the Roya Valley admits of a perspective that is at once in-depth and long-term. Immersion in the multiple layers of the border is a means of identifying all the lines that have become tangled up with it over time, from the validity of postage stamps to grazing rights for shepherds, from the use of a dialect to the price of a liter of wine, and, more recently, from requiring FFP2 face masks to having different mobile phone operators.

Furthermore, historical analysis helps in defamiliarizing the concept of borders and reminds us that, for a long time, state boundaries had little effect on mobility and migration. Thus, the Roya Valley provides fertile ground for the historicization of “transnationalism”: after all, transnational mobility is predicated on the existence of nations. The history of this valley shows that regional migrations that were not controlled by political institutions did not become transnational until states began taking control of them. Lastly, it breaks free from the methodological nationalism of qualifying migration differently depending on whether or not it involves crossing a border. In this case, for these border communities, migration was at once regional (Nice is less than 80 km away) and transnational from 1860 to 1947. The difference lies not in the practices themselves, but in how they were treated by the state.

My historical perspective is based chiefly on Italian and French public archives. While these sources do not admit of a focus on those governed by the state, my inquiry is not centered on the state either. Instead, I assume a vantage point between “ordinary” citizens and political institutions. Hence the importance of intermediaries, those who endeavor to make sense of issues that a priori hardly make any sense to ordinary citizens, and to take action accordingly: viz. local representatives of the state (particularly within prefectures), associations, town councils, etc. The concerns of ordinary villagers can be gleaned from these intermediaries, who claim to speak on their behalf, and from police reports (made by the renseignements généraux or carabinieri), which of course present a situated view. Nevertheless, some oral archives and interviews conducted in 2013 and 2014 serve to complement this study of border communities.

I had similar access to the national archives of both countries, though local sources are better preserved in the French archives. That said – and this is one of the lessons I have learned from consulting these archives – information about daily life in the villages in question seldom remains confined to the local level. The competent departments of both foreign ministries were regularly informed of supply problems and “political agitation” in the Upper Roya Valley. So a top-down and bottom-up approach to the public archives helps in tracing past information channels and chains of command, provides a window on the workings of past bureaucracy21. This is one way of doing ethnography based on archival documents, which involves examining the interdependencies between the various actors who produce the archives and reflecting on the effects produced by these materials22.

My analyses of the contemporary situation are by and large based on an ethnographic study I carried out in the Upper Roya Valley from 2012 to 2014, which involved staying on location twice (in the winter of 2013 and spring of 2014)23 and a number of round trips to the valley from Nice. During this period, I observed various forms of political activity in the valley, mostly with regard to an inter-municipal strategy adopted in 2012, the 2014 municipal elections, and efforts to defend the existing local train line, as well as some festive and more mundane events (e.g. street markets). I interviewed about fifty community leaders as well as candidates for and holders of elected office in these municipalities. After concluding the bulk of my fieldwork, I maintained contact with some interviewees in the valley and in Nice, and returned there occasionally, e.g. in July 2020 to present my work at the “Passeurs d’humanité” festival. Maintaining these contacts and monitoring the local press also kept me abreast of the situation in the Roya Valley in the aftermath of the devastating October 2020 flash flooding.

Political aura of the border calls for special state treatment

Working on border studies brings up questions about the specific effects of borders, i.e. the disparities between areas on either side of a given border, which some studies seek to measure – as well as particularities of border areas in contrast with adjacent areas in the same country but not along the border. Border regions are treated differently by the state insofar as it does additional work at its borders. This is another focus of my work: to show the specific institutional treatment reserved for border zones, and the effects thereof on those zones and their local communities.

Conceiving of a border as an alignment of boundaries helps in understanding this specific institutional treatment as well: one effect of such alignment is to reduce the scale of an activity, in some cases even the actual space at its disposal. Roads and other transportation routes in the Roya Valley are a case in point, one that also provides an opportunity to revisit the concept of “natural borders”, an idea particularly entrenched in mountainous regions, where the terrain may seem to impose itself on human activities. I’ve already mentioned the various salt routes running across the valley from the 13th to the 18th century. They were formed by a combination of natural and political factors, taking advantage of the most accessible mountain passes whilst keeping to areas that belonged to the Savoyard State, which gradually expanded to include Briga and Tenda in the late 14th and 16th century, respectively. So these storied transportation routes were shaped by both the physical landscape and political alliances. And, conversely, they affected socioeconomic activities in the areas they passed through, in particular that of muleteers, who had a monopoly on the use of the salt routes till 1784, when the entire “Royal Road” (which, incidentally, gave the valley its name) was opened up for public traffic.

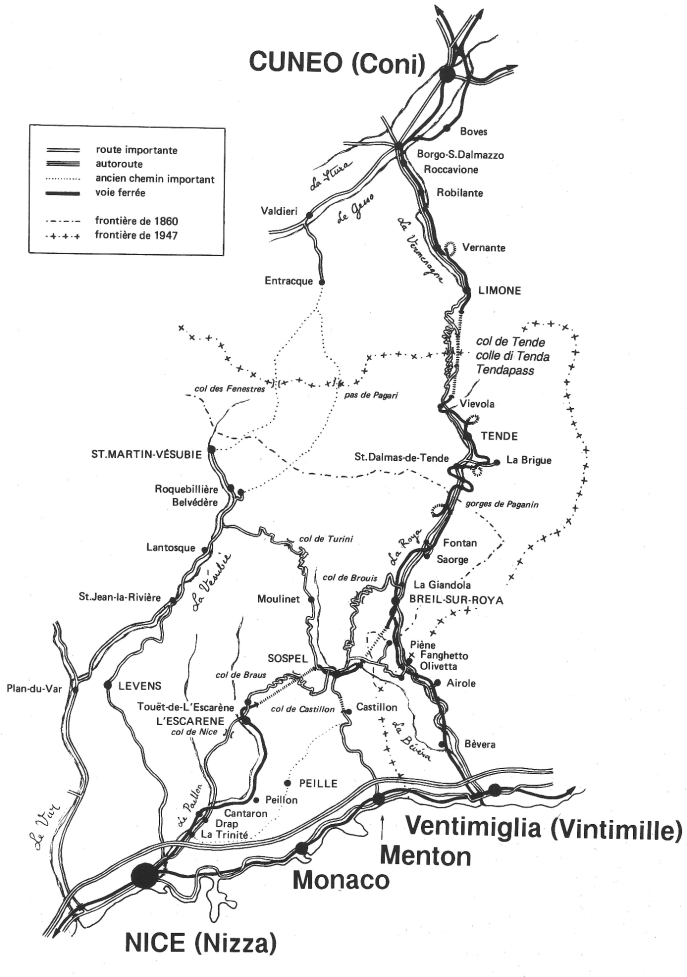

Map 3. Road and route map of the French-Italian Alpine border.

The Royal Road, which follows the course of the river, remains to this day the structural axis of the Roya Valley. Its upside-down Y shape is owing to the addition of a section connecting the mid-valley directly to the Côte d’Azur via Menton. In her PhD thesis on measuring border effects, geographer Sandra Pérez points out the market difference between transportation networks along the Franco-Italian border in the Alps and along the Franco-Spanish border in the Pyrenees.24 The main border crossing for the whole Franco-Italian area she studied is Col de Tende, with a secondary crossing at Col de Larche, whereas the Franco-Spanish border has fourteen border crossing points. Pérez contrasts a transportation network based on the concept of “drainage”, in which only a few roads cross the border, with the Franco-Spanish network that has numerous crossings, corresponding to the concept of “irrigation”. The former is more polarizing around the border and less conducive to cross-border traffic than the latter. In noting their effects on border traffic, it must also be borne in mind that their very shapes are the results of border effects. The shape assumed by these border-crossing networks at the Franco-Italian Roya border is the result of the alignment of activities along the border.

Sealed border and lopsided transport infrastructure since 1947

To this day, the Upper Roya Valley remains a “corridor” due to the combined effects of local topography and political choices. On its western side, the options are limited by the landscape and the massif’s highest peaks: Mont Clapier (over 3,000 m), Mont Bego (over 2,800 m) and Cime du Diable (over 2,600 m). The pre-1947 border line ran along the latter peak, leaving the higher ones on the Italian side. Topography and politics steered road development eastward before 1947. After 1947, conversely, nationalist rationale put a damper on the development of what were now border-crossing roads towards the east, while the terrain prevented the construction of new roads within the French borders. As a result, La Brigue became the dead end of a secondary road, despite the fact that the pre-1947 village had extended much further east, beyond the current border, and despite the many pedestrian and muleteer crossings there – including the salt route in the 15th century.

On the other hand, there have been plenty of plans since 1947 to build roads and tunnels – as well as ski resorts, and in some cases in connection with them – across or through the Alps in the Upper Roya Valley and in the Alpes-Maritimes department. The departmental council (Conseil Général) has had final say over the construction of new roads (and ski resorts) in the Roya Valley since 1947.25 In the 1990s, the Ligurian regional government deliberated on plans to construct a tunnel connecting La Brigue to Realdo, its former hamlet on the east side of the border, with a view to developing tourism and in particular the adjacent Monesi ski resort, which was built in the late 1960s. The municipality of Triora (which includes Realdo) also considered “ways to promote cultural relations and exchange in a place – Terre Brigasque – that has managed to preserve its ethno-linguistic and economic unity, notwithstanding its being divided up across three different regions and two different states”.26 In this commune, as well as in the town of Sanremo, an association has been formed to safeguard the Brigasque language and cultural identity, since minority languages are accorded greater institutional recognition in Italy than in France. But these plans came to naught – as did a “friendship road” envisioned in the 1960s following a similar itinerary, which remained a by and large impassable track on the French side of the border. A whole series of similar plans were scuttled over the years, giving rise to the situation Sandra Pérez observed in the late 1990s: a de facto sealing of the border east of the Roya Valley. The following map, published by a local history association in 1991, speaks volumes: it shows local roads and railroad lines in minute detail, as well as trails and tracks, on the French side of the border, but is “blank” on the east side, ignoring the ones beyond the French 1947-border.

Map of transportation networks in the Roya Valley

Source: Charles Botton and Michel Braun, Le Col de Tende: De la route du sel à la route de l’Europe, Breil-sur-Roya, Éditions du Cabri, 1991.

Border alignment weakened by Storm Alex in 2020

A major “Mediterranean incident” in the Roya Valley revealed other ramifications of its lopsided transportation networks: the de facto sealing of the border on the eastern side of the valley significantly hampered rescue and repair efforts – as well as being easy to break through. Intermittent illegal crossings immediately led to practical and political measures to reinforce the border.

When Storm Alex hit the Roya Valley, Tende and La Brigue were the last towns to be rescued – and the last, before that, to regain telephone and radio reception. They were cut off from the world for almost 48 hours after the storm hit on the night of October 2, 2020, destroying roughly 30 km of road and almost all the bridges in the valley. The French authorities announced that an emergency route would be opened up “before Christmas” (i.e. two and a half months later) and the road repaired within two or three years. They explained that road repairs in the Roya Valley were more complicated than in other valleys in the same department due to the absence of access routes to the road between Breil and Col de Tende. The road through the Lower Roya Valley, which is on the Italian side, reopened for traffic on October 5. Likewise, the road connecting the mid-valley to France via Col de Brouis was repaired almost immediately. But to the north of this area, reported the maintenance departments of the city of Menton and of the inter-municipal cooperation (IMC) between Menton and the Roya Valley, “We cannot make plans to restore certain roads or alternative routes temporarily [...] because, given the narrow configuration of the Roya Valley, all the roads need to be reconstructed progressively.”27 The departmental director of roads and infrastructures explained the “difficulty in the Roya” in similar terms: “There is only one entry point [...]. If we set up roadworks at the bottom, it will be hard to put another one behind it. We can’t pack in all that equipment.”28 By far the greater part of the French section of the valley, beyond Breil, seemed naturally and irremediably sealed on both sides, to the west and to the east.

And then, in this emergency, those tracks that had never really been turned into roads and those half-dug tunnels were suddenly rediscovered. On October 7, the prefecture of the Italian province of Imperia was requested to authorize French military engineering vehicles to use the “ridge road” – in reality, a severely dilapidated track that was closed to traffic – in order to access the Upper Roya Valley from the east. The Italian newspaper that ran the story underscored the “historical irony” of the situation: “The two villages, Briga and Tende, have become the symbols of the territory ceded to France in 1947 [...]. However, the emergency response machine is wholly focused on the present and not moved by nostalgia, of course, but by the awareness that, between cousins (lots of people have the same last name around here), it’s only natural to help each other out.”29 On October 9, the prefect in charge of the reconstruction reported, “We and the Italians have reopened the ‘friendship road’ that runs from La Brigue to Realdo [...] as long as there is no snowfall. This is the lifeline for valley-dwellers who take it to get to Italy.”30 That very day, Tende’s forest sappers opened access to the valley from the north by clearing a track connecting Tende to Limone Piemonte, bypassing Col de Tende via a small valley to the west – a track solely intended for shepherds, jeeps and quads.31 It provided access to the upper valley from Italy, to the north and east, long before the secondary road was cleared – and then only as a track with fords, accessible by convoy three times a day. The secondary road was not reopened until November 23, though only as far as Saint-Dalmas and La Brigue, and by Christmas all the way to Tende.32 In the meantime, the villages could only be accessed by helicopter. Without going into detail again, the restoration of the rail network showed a similar pattern: the line from Nice to Breil was the first to be repaired, beyond which Italian trains arriving from the north eventually reached Tende la Brigue and Saint Dalmas de Tende, serving as the primary means of transportation between these villages for the time being.

Map 4. Transport infrastructure conditions in Roya Valley one and three weeks after Storm Alex.

Map 5. Transport infrastructure conditions in Roya Valley one and three weeks after Storm Alex.

Storm Alex revealed how lopsided transport infrastructure in the valley has become over the years and, paradoxically, how precarious the “watertight” seal thereby created at the border still is. Hence the need for the French state to reaffirm its presence. Tende’s mayor made this explicit, repeating to various media outlets (including BFMTV on October 6) that during the 48 hours in which the village was cut off from the world, “We wondered if we were still part of France.” So the French state made a show of its active commitment to maintain sovereignty right up to the outer edge of French territory. Emmanuel Macron’s flying visit to Tende on October 8 was the first visit ever paid by a French president to the Upper Roya Valley: to be sure, senior Gaullist officials had visited after the region’s annexation, but never the president himself. On this occasion, Tende’s mayor declared that, although it had been a long time coming, “I’m impressed by the French machine when it gets going.”33 French sovereignty was expressed somewhat more prosaically by helicoptering food in from Breil to the Upper Roya Valley, and having refuse helicoptered out by Véolia, the French utility in charge of waste management for the Menton inter-municipal cooperation, even after train service was restored from Italy to the Upper Valley.

Conclusion

The long history of the Roya Valley is marked by the successive alignment, displacement and realignment of a skein of boundary lines that has formed at the border, and that history sheds light on border effects on the area and on social and economic activities delimited by the border. The imposed alignment of numerous practices that are directly dependent on political institutions has led to a lopsided transportation infrastructure as well as producing indirect effects on watershed management, political mobilization, language practices, the job market, etc. These various boundaries combine more or less coherently to form a border skein, which needs to be parsed closely in order to truly understand how borders affect local practices: in other words, what borders do to border areas and the social groups they contain.

Notes

1

Noel Parker and Nick Vaughan-Williams, “Lines in the Sand? Towards an Agenda for Critical Border Studies”, Geopolitics, no. 14, 2009, p. 582-587.

2

Cf. inter alia, Sabine Dullin and Étienne Forestier-Peyrat, Les frontières mondialisées, Paris, PUF, 2015; Paolo Cuttitta, “La ‘frontiérisation’ de Lampedusa, comment se construit une frontière”, L’espace politique, no. 25, 2015; Anne-Laure Amilhat-Szary, Qu’est-ce qu’une frontière aujourd’hui?, Paris, PUF, 2015; Michel Foucher, Le retour des frontières, Paris, CNRS éditions, 2016.

3

Cf. inter alia, Alain Tarrius, La mondialisation par le bas: les nouveaux nomades de l’économie souterraine, Paris, Balland, 2002; Geneviève Cortes and Laurent Faret, Les circulations transnationales. Lire les turbulences migratoires contemporaines, Paris, Armand Colin, 2009; Franck Mermier and Michel Peraldi (eds.), Mondes et places du marché en Méditerranée. Formes sociales et spatiales de l’échange, Paris, Karthala, 2010.

4

Daniela Trucco, “Prendre en charge et mettre à l’écart. La ville, la frontière et le camp à Vintimille (2015-2017)”, in Politiques des frontières, Paris, La Découverte, 2018, pp. 145-160; Daniela Trucco, “La (re)frontiérisation de la ville de Vintimille dans le contexte de la ‘crise des réfugiés’ (2015-aujourd’hui)”, in Actes du colloque Pridaes XI. L’intégration des étrangers et des migrants dans les États de Savoie depuis l’époque moderne, Nice, Serre Editeur, 2019, pp. 329-342; Livio Amigoni et al. (eds.), Debordering Europe: Migration and Control Across the Ventimiglia Region, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2021.

5

Lucie Bargel, Dans l’écheveau de la frontière. Alignements et réalignements des attachements politiques dans la Roya (XIXe-XXIe siècles), Paris, Karthala, 2023.

6

Sabine Dullin uses the expression épaisseur (thickness or depth) to stress that a border is not so much a line as a zone. Sabine Dullin, La frontière épaisse. Aux origines des politiques soviétiques, 1920-1940, Paris, Éditions de l’EHESS, 2014.

7

Michael Mann, The Sources of Social Power: Volume 1: A History of Power from the Beginning to AD 1760, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1986.

8

Pierre Rosanvallon, L’État en France de 1789 à nos jours, Paris, Seuil, 1993.

9

Léonard Dauphant, “Le royaume des quatre rivières: l’exemple de la frontière de la Meuse de Philippe IV à François 1er”, in Michel Catala (ed.), Frontières oubliées, frontières retrouvées: Marches et limites anciennes en France et en Europe, Rennes, Presses universitaires de Rennes, 2016, p. 223.

10

Daniel Nordman, Frontières de France: de l’espace au territoire, Paris, Gallimard, 1998, p. 511.

11

Jane Burbank and Frederick Cooper, Empires in World History: Power and the Politics of Difference, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2010.

12

Wendy Brown, “Finding the Man in the State”, in States of Injury: Power and Freedom in Late Modernity, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1995, p. 191.

13

Michael Billig, Banal Nationalism, London, Sage, 1995; Michael Skey, National Belonging and Everyday Life: The Significance of Nationhood in an Uncertain World, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

14

Peter Sahlins, Frontières et identités nationales: la France et l’Espagne dans les Pyrénées depuis le XVIIe siècle, Paris, Belin, 1996, p. 25.

15

Michael Skey, National Belonging and Everyday Life: The Significance of Nationhood in an Uncertain World, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2011, p. 5.

16

Rogers Brubaker et al., Nationalist Politics and Everyday Ethnicity in a Transylvanian Town, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2008.

17

Hélène Dumas, Le Génocide au village. Le massacre des Tutsi au Rwanda, Paris, Seuil, 2014.

18

Daniel Nordman, Frontières de France: de l’espace au territoire, Paris, Gallimard, 1998, p. 10.

19

Didier Bigo, Riccardo Bocco and Jean-Luc Piermay, “Logiques de marquage: murs et disputes frontalières”, Cultures & Conflits, no. 73, 2009, pp. 7-13.

20

Veena Das and Deborah Poole, Anthropology in the Margins: Comparative Ethnographies, Santa Fe, SAR Press, 2004, p. 6.

21

François Buton, “L’observation historique du travail administratif”, Genèses, no. 72, 2008, pp. 2-3.

22

Frédérique Matonti, “‘Ne nous faites pas de cadeaux’. Une enquête sur des intellectuels communistes”, Genèses, no. 25, 1996, pp. 114-127.

23

Made possible, along with my study of public archives in Paris, Rome and Turin, by a one-year delegation from the CNRS to the CESSP and additional funding from the TEPSIS.

24

Sandra Perez, Analyse spatiale des régions frontalières et des effets de frontière: application aux espaces frontaliers franco-espagnols du Pays-Basque et de la Catalogne, et à l’espace franco-italien des Alpes-du-Sud, PhD thesis in geography, University of Nice, 1999.

25

Ownership of the main road through the valley was also transferred to it by the French government in 2008.

26

Private archives of A Vastera, document dated July 20, 1993.

27

Nice-Matin, “live” online, October 8, 2020.

28

“Une quinzaine de chantiers sur les routes de la Roya”, Nice-Matin, October 25, 2020.

29

“Le ferrovie francesi chiedono aiuto a Roma. Un ponte di fuoristrada per rompere l’isolamento di Tende” [French Rail asks Rome for help: An off-road bridge to put an end to Tende’s isolation], Il secolo XIX, October 7, 2020.

30

“Roya, Tinée, Vésubie: ‘aller vite, avant l’hiver’”, Nice-Matin, October 9, 2020.

31

Nice-Matin, “live” online, October 9, 2020.

32

“Le train se fait attendre”, Nice-Matin, January 18, 2021.

33

Nice-Matin, “live” online, October 8, 2020.