This article focuses on an area of study that, in Europe at least, does not constitute an isolated field within the social sciences and humanities. Since research into the formation of racial categories is not confined to one disciplinary framework, nor to any fixed intellectual traditions, we can hope to greatly benefit from this fluidity. This same reason, however, makes it difficult to tackle such a vast field of reflexions and knowledge. The present essay is therefore intended precisely to open up a debate in Politika, by drawing upon the experience of the author, a researcher in the history of European and the Americas under the Ancien Régime. My aim throughout is to emphasise what an historical approach may offer, in terms of perspectives, to the social sciences in general. The ensuing discussion will, I hope, be contradictory – given that among historians, at least, no consensus exists on how to tackle the history of the processes of racialisation.

The Present Moment

Today, the question of race is posed on a global scale1. On the one hand, Western countries – regardless of whether or not they constructed colonial empires in the nineteenth century – have to deal with manifestations of racism, corresponding variously to cases of police brutality in the US, the unleashing of racist rhetoric in Europe in the face of the migrant crisis, or “chromatic” social hierarchies in Latin America. On the other hand, interethnic and interdenominational violence, as well as the fragmentation of caste-structured societies, based on ideologies of purity and heredity, seem to be present on all continents. Nonetheless, in the interest of avoiding simplifications and approximations regarding situations that might be observed in Asia and Africa – which call for the publication of complementary articles – the present article focuses solely on Western societies in Europe and the Americas.

From a social science point of view, the present moment is marked by a paradox. For some sixty years now, researchers in the social sciences have acknowledged, by broad consensus, that the notion of race holds no pertinence for the analysis of human societies, either to describe their internal cohesion or to define what distinguishes them from one another. The constructivist model, which understands race to be a social and cultural artefact, is the only one used to underpin the works of historians, sociologists, anthropologists, political scientists and philosophers2. These academics are reassured in their approach by the fact that geneticists themselves reject the concept of race, regarding it as a vague notion that is incapable of denoting pertinent distinctions between human groups3. Nevertheless, the prevention of genetic health disorders relies on the identification of risk populations – that is to say the heightened probability that particular genes will be found in certain populations rather than others. Common sense attitudes, meanwhile, are strengthened by that timeless experience of the discovery of resemblances between children and their biological parents. Thus, when the social sciences borrow the assertion – taken from the public rhetoric of geneticists – that races do not exist, this is to say that no inference of a social nature can be drawn from the genetic variations between individuals or groups. Yet, while the social sciences have seemed committed in their desire to prohibit physiology from interfering with their field of analysis, biologists have begun to decipher the codes that can offer a better comprehension of the biochemical mechanisms governing the intergenerational transmission of physiological characteristics. In other words, the constructivist paradigm occupies the entire intellectual space of the social sciences at the very moment that, for the first time in the history of humanity, the biological sciences in their laboratories have become capable of describing the causalities that are inscribed in our genetic heritage4.

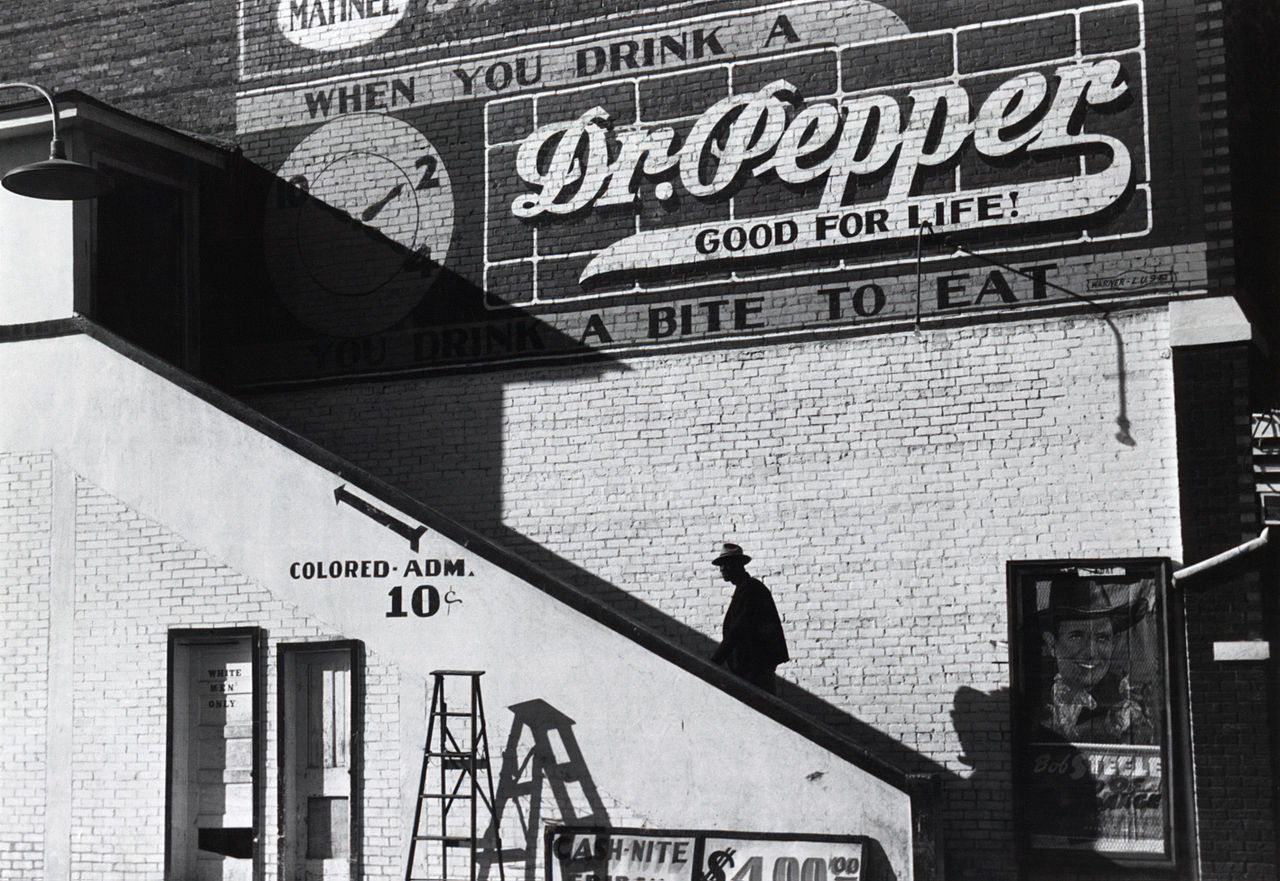

A black man enters a movie theater in Belzoni, Mississippi, in 1939.

Despite the feeling that a global perspective on race is pertinent to research (and to public policy), all humanities and social science analyses of such issues are, by definition, situated. Race is not written about in the same way in France or Germany as it is in Great Britain – and even less so in the United States or Latin America. The histories of our countries have left us with highly divergent legacies in relation to aspects that are essential to the understanding of racial politics. European countries continue to face the very long-term consequences of two historic upheavals. The first is Europe’s suicide between 1914 and 1945, and more specifically the human, material, and moral destruction wreaked by the Nazi project. The second is the pendular motion from contemporary colonisation to decolonisation. The US and the majority of Latin American countries, for their part, must deal with the double legacy of the Amerindian genocides and mass slavery.

All social science studies are situated and presuppose a commitment to a work of reflexion that accompanies empirical research. This is the basic programme for the production of knowledge about human societies. But situating oneself does not mean occupying a position that, by its very nature, either facilitates or inhibits the undertaking of the research. A gender identity, a racial label, a social legacy – should it be accepted that these positions constitute certain conditions of intellectual activity that cannot be neutralised by the reflexive process? In other words, can the racial experiences of subjects who do not share the same racial status as the investigator be taken as an object of study? In this respect, this article is grounded in a rejection of relativist standpoints. This conviction is based on a piece of logical reasoning borrowed from Gérard Lenclud: namely, in order to affirm that any notion, attitude, gesture, ritual, text, or institution under analysis is untranslatable and incommensurable, one must nonetheless have understood and measured it5. Moreover, the capacity to take stock of one’s own position within the racial sphere – as in the sphere of gender or class relations – does not in any way imply that one should hold back from studying the experiences of men and women whose trajectories are extraneous to us. To my mind, the claim that scientific universalism is a reflection of ideological universalism – and, consequently, a remnant of colonial imperialism – is a sophism.

Race and Race: Contrasts between France and the United States

On a political level, the French case and that of the US are almost unilaterally opposed. On one side we find a persistent refusal to authorise the establishment of ethnicity statistics6; on the other, a long practice of categorising populations (Caucasians, African Americans, Native Americans, Latinos, Asians, etc.), or of ethnic and phenotypic self-identification (notably in Brazil)7. On one side, a penal law that restricts the right to the expression of racial hatred; on the other, an unconditional and unbridled defence of the freedom of speech. In the case of France, we can find a political movement that promotes a racialised vision of French identity (the Front National) but which never releases any discourse (aside from slip-ups on a local scale that are out of the party leadership’s control) that might fall afoul of the laws obstructing public expressions of racial hatred. Through the staged “de-demonisation” of this far-right party, we can also see how it is possible for a political movement that springs from racist roots to dispense with discourses on the inequality of races, as they existed up until 19458.

With regards to the humanities and social sciences, the divergence is just as great. The article “Race” in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy offers a meaningful example in this respect. The bibliography provided alongside the entry makes no reference to any non-Anglophone research, even in translation. Following an account in the form of an introduction to the history of racial categories from Aristotle to the Enlightenment period, the article focuses on the US, essentially around the case of African Americans, with some brief notes on Latinos or Jews. This approach is coherent, inasmuch as it is presented as being centred upon a particular region and society. However, the first lines of the article make scant mention of its limitations, and indeed claim to offer a definition of the concept of race in general:

“The concept of race has historically signified the division of humanity into a small number of groups based upon five criteria: (1) Races reflect some type of biological foundation, be it Aristotelian essences or modern genes; (2) This biological foundation generates discrete racial groupings, such that all and only all members of one race share a set of biological characteristics that are not shared by members of other races; (3) This biological foundation is inherited from generation to generation, allowing observers to identify an individual’s race through her ancestry or genealogy; (4) Genealogical investigation should identify each race’s geographic origin, typically in Africa, Europe, Asia, or North and South America; and (5) This inherited racial biological foundation manifests itself primarily in physical phenotypes, such as skin color, eye shape, hair texture, and bone structure, and perhaps also behavioral phenotypes, such as intelligence or delinquency”9.

The fifth part of the definition claims that the dominant manifestation of racial difference rests upon the existence of distinctive physical phenotypes. This assertion is based upon an empirical evaluation centred upon the African American case. It emphasises the expression of intrinsic differences through phenotype. It therefore casts aside the hypothesis that processes of racialisation may be fed by the erosion or disappearance of external signs of difference in phenotype, or on account of phenotype. This point is certainly the most debatable aspect of the entry, and the present article proposes an alternative to it. Yet the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy text also takes up the notion of “behavioural phenotype”, which, in current medical vocabularies, relates to syndromes of mental deficiency with a genetic origin. Indeed, among racial theories, the notion of behavioural phenotype breaks free of its framework of medical usage, in order to designate social performances or attitudes that have nothing to do with the syndromes described by medical doctors. Among certain current debates in the US, the notion of a “behavioural phenotype” of intelligence evokes a genetic foundation for the intellectual performances of the dominant (White Anglo-Saxon Protestant) group, but also of Jews – while delinquent behavioural phenotypes conjure up (who could ignore it) the acknowledged levels of criminality within the African American population.

Martin Luther King III on CNN after the riots in Ferguson, Missouri, in August 2014.

The manner in which this issue is tackled by the humanities and social sciences in Western Europe, in general – and most exceptionally in France – is quite different. It is, first and foremost, a matter of vocabulary. In the contemporary French language, the term “race” has disappeared completely from researchers’ vocabularies. This is explained by the fact that the term’s meaning has undergone a radical narrowing since 1945. When “race” has been mentioned in France since the end of the Second World War, it has been only to refer to the biological unity of a given population. When restricted to this sole meaning, the term race can no longer therefore be used to designate people, cultures, or nations – or any other mode of designating populations by their cultural, social, or political characters. If truth be told, the repugnance that the word incites within the intellectual world is such that it is not even used to designate coherent populations on a biological level. A recourse to alternate phrasings always seems preferable to employment of the term itself – as if, in reality, it were now impossible to isolate the term from the sociological inferences that might have stemmed from it prior to the 1950s; as if the memory of the crimes committed in its name prohibited its use. As a result, not just disreputable politicians of the Front National, but also French researchers in the humanities and social sciences are torn between contradictory lexical usages. We continue to designate all sorts of collective discrimination as “racisms” (commentators have been known to wax lyrical about racism against young people, racism against old people, etc.), while at the same time the term “race” – which should be the point of reference upon which political racisms are founded – remains absent from discourses about the state of society, even among racists.

The desire to categorically eliminate the term race from the public sphere – not to mention from legitimate language – made a comeback in 2012 when the presidential candidate François Hollande committed himself to eliminating the term from the French legislation and constitution. Indeed, the first article of the Constitution of the Fifth Republic states: “France shall be an indivisible, secular, democratic and social Republic. It shall ensure the equality of all citizens before the law, without distinction of origin, race or religion. It shall respect all beliefs”. The future president expressed his argument in the following terms: “The Republic shall not fear diversity. Diversity is movement, life. There is no diversity of races. There is no room in the Republic for race”. Jurists and human rights defenders were quick to observe the futility of this verbal censure, which, they argued, could have the consequence of accentuating the public authorities’ incapacity to clearly designate processes and attitudes that feed discriminations of a racial character10. Here we find ourselves virtually at the antipode of the linguistic usages that can be observed in the US, both in the public sphere and the academic world.

Proposals for a Definition

In spite of these lexical ruses and moral concerns, bringing social science research to bear upon the topic of race means identifying a hard, specifically racial core among the range of prejudices, phobias, political programmes, and productions of norms that are labelled – somewhat vaguely – as “racist”. This article focuses on the part that historical research can play in the interdisciplinary discussions of these phenomena. It aims at stimulating reactions and invites discussion with not only historians, but also with sociologists, anthropologists, political scientists, and philosophers. The objective, then, is to determine what historical research can clarify in debates about the development of racial categories as a political resource in human societies. In this respect, research in history strives towards three goals:

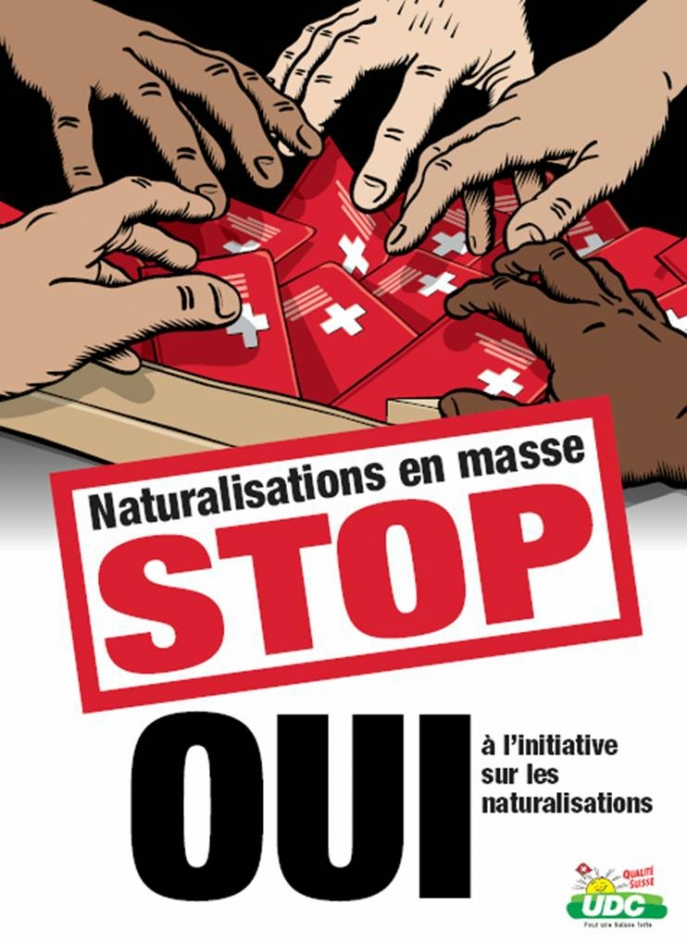

Posters for the Swiss popular initiative "For the Dismissal of Criminal Aliens (Removal Initiative)" and "For Democratic Naturalisations", launched on 10 July 2007 and 1 June 2008 by the UDC, as well as a counter-campaign for the first initiative.

Pick out racial categories and processes of racialisation from among the broader range of xenophobic attitudes and policies. Fear or rejection of others can be observed in any place, at any time, and, above all (and most crucially on a methodological level) at any scale: for instance, between two neighbourhoods in a village; two villages in a valley; two districts in a region; two regions in a nation; or among different nations. At all levels, then, quarrels can emerge; they are neutralised, however, through different scales of conflict. The task of defining or describing what constitutes the alterity of the other only occurs if actors demonstrate collectively that they have the capacity to put content to that identity and to that alterity, for themselves and for the ones from whom they wish to be distinguished. Yet xenophobia does not involve any special social competence, because it can refer to anything. Hence, social science research into the formation of racial categories requires more precise objects of study than a vague feeling of rejection towards another, or even the routine spreading of negative stereotypes.

Propose a chronology for the phenomenon of racial category formation in Western societies, which is not limited to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Certain historians have reconstituted debates and knowledge that were around in much earlier periods. This is the case of the classical era, for example, where certain recovered texts (and images) show traces of arguments about heredity or climatic variations11. In their later years, authors such as Hippocrates and Galen were recognised as authorities on issues such as congenital malformations in individuals, or the influence of food or climate on people’s nature. For centuries, geographers like Herodotus, Strabo, Pliny the Elder, and Ptolemy paved the way for imagining the division of societies into differentiated natural and social groupings12. Among Aristotle’s writings we find the ideas that give license to the interpretation that distinctions between masters and slaves are owing to the latters’ inferiority13. From the European Middle Ages, through the Renaissance, and into the Enlightenment: in so many periods, instances of relegation, discrimination, and persecution have found political justification through racial conceptions of alterity.

Slaves working in a mine in Ancient Greece.

Prepare humanities and social sciences researchers, students, and citizens to confront the yet unknowable challenges that may be presented by the outcomes of research in genetics. Of course, it is imperative to go on denouncing the ideological agenda and racist politics of sociobiology14. However, we should not indulge in the belief that the humanities and social sciences can continue developing their own skills without paying attention to what genetics might say in future regarding the development of humans in society.

The pursuit of these various objectives rests on a set of definitions of race, which can be articulated around three points:

Racial prejudices presume that the social and moral (or cultural, religious, political, etc.) characters of individuals and groups are transmitted from generation to generation through vectors located in the tissues and fluids of the human body (blood, sperm, milk). When the conditions are assembled on an ideological, normative, and political level, historians should not interpret fluids such as blood, sperm, and milk as symbols, images, or metaphors, but rather as the material things themselves. If blood merely constitutes the metaphorical expression of a spiritual principle or social process, then this is not a racial definition of identity (or of alterity, which amounts to the same thing).

The discovery of America, May 12, 1492. Christopher Columbus erects a cross and baptizes the island of Guanahani named St Salvador (engraving from the book Great Travelers by Th. De Bry, circa 1590).

Racial discrimination rests on the idea that, whatever the political circumstances and the efforts made by an individual, family, or group to reduce the distance separating their minority or minorities from the social majority to which the individual, family or group intend to belong, there remains something immutable that renders vain or impossible their aspiration to truly join the social majority. In a metaphorical or – more often – real sense, the site of this irreducible remnant remains the body. This incapacity to change, or to rid oneself of a legacy (or inheritance) inscribed in one’s physiology affects all individuals and all families belonging to the stigmatised group in equal measure.

The fundamental aim of all racist policies is to impede the processes by which marginal or stigmatised populations could be integrated into a common political space at the heart of the society in which they live. In other words, when the members of a family or group become involved in a process of social and political transformation that aims to reduce the distance separating them from majority society, the politics of racialisation consists in denying the erasure of their differences, holding these to be indelible, present, and inscribed in the bodies of all individuals in the group. Racialisation is aimed at delaying the processes to close the gap between different conditions. If the alterity that is inscribed in the other’s body is unalterable, since it is rooted in a nature deeper than any social appearances, the vision of a shared sense of belonging, or a disappearance of differences, is denounced in racial thought as a dangerous illusion.

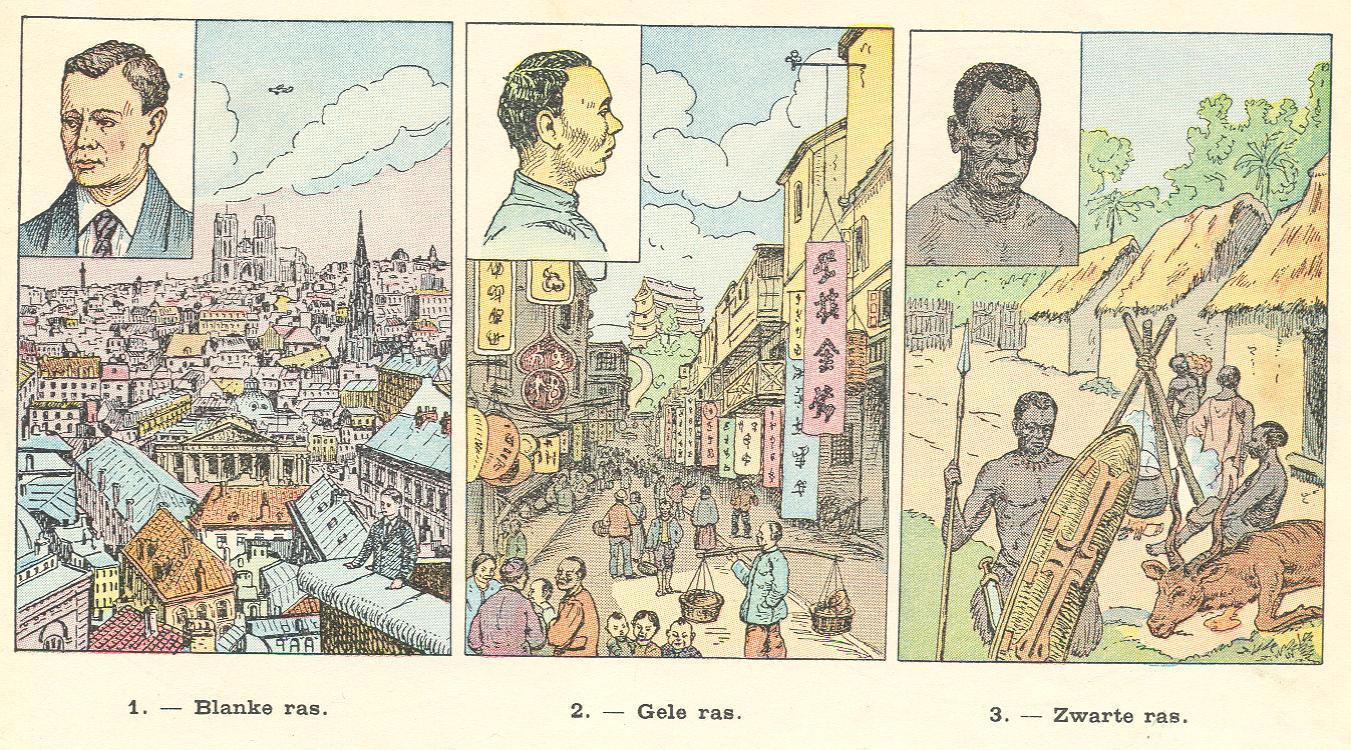

The classification of humans in three races (Procure, circa 1950).

According to these three defining elements, therefore, racism does not consist in rejecting an alterity that is defined as a stable and manifest (in other words visible) reality. For this would be the definition of any type of xenophobia. Racism, which should be understood as a more restricted political form, is a programme of action that consists in producing alterity within society in order to feed a mechanism of distinction, relegation, stigmatisation, and discrimination. Historical research into the formation of racial categories thus encounters various methodological and theoretical uncertainties. Explicitly outlining a certain number of these difficulties remains the best way to assess the current state of affairs in relation to these questions.

Racism as Ideology

Without training in historical semantics and philology, it is useless to claim the ability to interpret documents that are no longer contemporaneous to us. However, knowing the state of the languages in each of the periods that form the focus of our research should not serve to limit the questions that we pose about the societies we study. Therefore, the fact that the term “racism” did not appear in Western languages until the twentieth century should not be used to support the argument that the phenomenon could not have existed without the word. In this respect, it is no more outlandish to speak of “racisms” in relation to the seventeenth century than it is to refer to “slave societies” from the same period. Indeed, the idea of slave societies was as yet unformulated and unthought of, since the words to describe such an idea did not exist, even though some American societies comprised many more slaves than free subjects.

In terms of its analytical framework, this article takes neither socioeconomic domination – whose examples par excellence are the slave trade and slavery – nor physicality – of which the most obvious manifestation is skin colour – as a starting point. In no way does this mean that the intensity of the mass crime that was the transatlantic slave trade (nor, after the abolition of slavery, the violence of the Jim Crow laws or Apartheid) should be underestimated. There is no doubt that – along with the Nazi regime and its legislation – these juridical measures share the accolade of the most racist policies of the Western world during the contemporary period. Even today for scholars of the US, the most commonly studied topics to do with the issue of racial discrimination remain, precisely, domination under the system of slavery, and colour. Within this framework, the historiographical debate has been nourished by the opposition of two explanatory models for the cruelty, the capacity for dehumanisation, and the magnitude of the transatlantic slave trade15. According to some scholars, this system was made possible by a long, prior history of stigmatisation and contempt towards African populations in Renaissance Europe16. For others, it was the mode of production resting upon the massive exploitation of slaves that evoked the creation of discourses (and images) to justify this abomination, by representing the natural inferiority of its victims17. The historical, and indeed current reasons for the fact that American research has remained focused upon the long-term effects of the transatlantic slave trade are both obvious and legitimate. In Europe, nevertheless, we can set out from a viewpoint that is somewhat removed from the dominant tone of scientific output on these issues, but which remains engaged in permanent dialogue with researchers from the United States and Latin America.

The chart "Stages of Growth for Members of the Nordic Race" in Germany, in the 1930s.

It is worth identifying here what the research of historians can help us understand in particular, from among the wider collectivity of the humanities and social sciences. In Europe – as in the United States and Latin America – sociology, ethnology, political science, philosophy, and art criticism compete – alongside history – to aid our understandings of the phenomena of racialisation, racist behaviours, and the expression and dissemination of racial prejudices. This article aims to show that a methodological preference for chronological depth (that is to say, a longue durée approach) produces knowledge and proposes specific angles of analysis that are not offered by the other disciplines of the humanities and social sciences. The proposals outlined here are, in large part, the result of the continuing unity of the humanities (including the literary domain) and the social sciences in France. Once again, this is a difference in relation to the way that the disciplines are distributed in the US – namely, now, with a marked division between the social sciences and the humanities in the majority of universities.

If we say that racial distinction is available as a political resource in a given society, this means that we are dealing with an ideology – something much more substantial and articulated than a mere collection of stereotypes. Numerous historians have dedicated themselves to creating inventories of all sorts of representations of cultural alterity, at all times and in all places, with as many sources as can be used in this way. From the depiction of shackled prisoners with Negroid features in Egyptian bas-reliefs to the poster for the film Jud Süß by Veit Harlan (1940), touching upon various other repertoires along the way, we can piece together histories of the formation of images of the Other. These artefacts (texts, images, objects) most often have a dual and indivisible aim: to record a difference and to engender a distinction. From the moment that we launch into an analysis of the contents of stereotypes, we refrain from understanding the process of distinction. For these inventories most frequently deliver tautologies, like: for Europeans “the African is always inferior for he is described as an ape-like being”, or “the Jew evokes disgust because the portraits made of him are repugnant”. Any informational progress is very quickly exhausted in these types of study. In contrast, because they are more demanding, approaches that focus on ideology offer all kinds of other perspectives. In the manner of Giuliano Gliozzi18, then, it is important to understand – or rather comprehend together – the socioeconomic system, the political-institutional and normative framework, as well as the expressive and interpretative accounts of the world that gave birth and sense to those hostile manifestations, and to the desire for the relegation of stigmatised populations. This sort of analysis allows us to perceive the links between discourses on race and the courses of action found among all the implicated parties, including the victims of stigmatisation.

Nothing can better help us understand the difference between a series of stereotypes and attitudes of defiance, and a grounded ideology of race, than (to use the expression of Georges Balandier) “colonial situations”19. The creation of colonial societies rests on three factors: 1) the substitution of local political authorities for agents (foreign or local) who report back to the colonising country’s political institutions on the exercise of control; 2) the settlement of new residents from the colonising region, and the capture of economic resources – beginning with the best lands – to the advantage of the colonisers; 3) the production of a legitimising discourse – in other words a doctrine – that gives the phenomenon meaning and follows its evolution. When historians reconstitute stages of the formation of racial ideologies in colonial situations, they analyse the social, political, and cultural processes that defined the rules of hierarchisation in social relations, as they were understood and taken up by the dominators as well as the dominated. These studies are conducted across highly diverse terrains, from the diminishment of the autonomy of Irish society by the English in the High Middle Ages20, to the laying bare of the trap that held colonised and colonists in an inexorable conflict in the writings of Frantz Fanon or Albert Memmi21, or indeed the allocation of a distinct territory for Amerindian subjects of the King of Spain, as testified by the great manuscript of the noble Peruvian Felipe Guamán Poma de Ayala at the end of the sixteenth century and the beginning of the seventeenth22. In any history of racial ideology, the colonial – and now postcolonial – question must occupy an important place.

A Red Herring: The Norms/Practice Opposition

Racial logic and racial politics are not merely oriented towards giving form and legitimacy to relationships of domination. During the long history of the formation of Western societies, the assurance that people’s qualities and aptitudes were transmitted intergenerationally via the vector of the body was first used to ensure the longevity of the privileges enjoyed by noble families. Thus, it was as much in view of the selection of the best as it was the stigmatisation of the worst that the racial argument was mobilised. To take the felicitous phrase of Charles de Miramon: “medieval society presented itself as a meritocracy of the virtuous, even though its social reproduction was based on heredity”23. Of course, selection and stigmatisation are each constructed in the mirror of the other. Superior qualities are transmitted by the same channels as inferior ones, usually starting with blood. For centuries, this precious liquor has been attributed the capacity to transport people’s moral and social characters. Historians are in disagreement over one point: should the vehicular faculties that were attributed to blood be understood as a symbol or as an actual power? For better or worse, the social efficacy of linear transmission permits us to advance the idea that a purely metaphorical reading of the function of blood is unjustified.

Indeed, numerous inquiries into present or past societies have shown that the norms regulating racial segregations were applied in a more or less radical fashion. When we study the assignment of identity by contemporary bureaucracies, or even gestures of self-definition by actors themselves, we find that people can change identity over the course of their lifetime. This assessment impels us not to take racial norms completely at face value, as an historical or sociological source offering a reflection of the organisation of social life. Within the framework of historical research, achieving chronological depth and a knowledge of lineages through genealogical inquiry can lead to a similar scepticism. We can therefore document the fact that numerous families gradually escaped the racial conditions assigned to them by contemporary norms. However, two objections can be levelled at this type of approach. On the one hand, the norms/practices opposition is always a problem with a foregone conclusion: namely, that practices differ from norms. People do not behave like subjects upon whom juridical texts impose instructions and prohibitions. This disjunction can be observed everywhere and at all times, and therefore demonstrates nothing very specific. To the eyes of the humanities and social sciences, however, it is only in singular circumstances that actors’ behaviours incorporate various more or less formalised norms, and that the production of norms itself is preoccupied by the rules of social life. Then again, being able to show that certain individuals from the stigmatised group were able to escape the stigma in no way counts as proof that the processes of stigmatisation were inactive.

Le White Only Beach in South Africa, in the 1940s.

The case of US segregation after the Civil War offers an historical example of this phenomenon. The society was permeated by the principle of the “one-drop rule” – in other words, the rule of hypodescent, according to which the stigmatised origin (even when present as a mere trace) defines the individual’s character and place in the social hierarchy24. Above all in its southern regions, American society had introduced discrimination laws regarding the uses of public space; prohibited mixed-race marriages; and moved to deprive African American citizens of their right to vote. This same society was home to the phenomenon of “passing”: namely, the implementation of a personal programme under which an individual of partially African origin may pass as “white”. If applied here, the “practices vs. norms” argument would invite us to assert, based on the numerous cases of passing, that the general system was not really racist. Of course, paying attention to the social configurations that gave rise to the phenomenon of passing naturally leads to a focus on the various resources that individuals mobilised in order to escape their condition. And isn’t wishing to rid oneself of a stigmatised origin the best proof that this origin was an obstacle, even a source of shame? In this case, the possibility of ridding oneself of the stigma does not reveal the latter’s fragility, but rather its robustness.

In more ancient periods, where there is an even greater opportunity for hindsight, the norms/practices argument seems more fragile still. When we begin to examine a genealogy over a large number of generations, the probability of discovering a racially suspect component within it increases – and it was exactly upon this likelihood that the Inquisition rested its repressive authority, when it demonstrated its capacity to identify suspect origins at the level of 1/64th of an individual’s blood, in Spain in the sixteenth century. Despite the high probability of no one being able to avoid having some nefarious origin in their ancestry, historians should not suppose that the rules designed to exclude suspected individuals were barely or not at all applied. We cannot theorise about individuals’ capacity to avoid a racial condition over the course of one lifetime and over several generations, as if the same social and legal processes were active in both cases. In terms of achieving the erasure of a stigmatised racial condition over several years, several decades, or even several generations, for the individuals concerned these results are as far from one another as total failure is from complete success. Historians are supposed to pay close attention to the ways in which human experiences are inscribed within a given time period. To take stock of the ancestry of a certain family line over the course of five generations is to conduct an operation that no actor could experience nor be aware of – in particular the members of earlier generations, who gave rise to the process.

The norms/practices opposition is of the kind that delivers the conclusions of an inquiry even before it has begun. What is demonstrated by colonial experiences and racist societies is that personal mobility – prompted by the desire for a change of status – reveals not the ineffectiveness of racial categories, but rather the importance that individuals attach to the possibility of extricating themselves from the latter. In short, a mixed-blooded society is not a society that effaces all racial barriers.

Fixity and Degeneration

The theory of the fixity of human conditions posits that no accident of a social or historical nature is capable of modifying individuals or populations. Such a viewpoint may spring from a polygenist perspective of the history of humanity, according to which the Earth is inhabited by several distinct species of human beings. This view is particularly apt to support political projects whose aim is to keep separate populations that are held to be differentiated. Polygenesis seems the ideal theory for an ideology that binds individuals and groups within a natural form of identity that is forever fixed, and that justifies segregation, hierarchisation, and even slavery. Monogenesis, on the other hand, holds firm to the biblical account, which conceives of a sole humanity with a common origin; this interpretative framework is supposedly most suited to universalist, relativist and evolutionary models. In reality, though – as Silvia Sebastiani has shown in her works – the allocation of roles between polygenesis and monogenesis is not so simple, if we examine these concepts’ respective contributions to the spreading of a racial conception of human diversity25.

The work of classifying and shaping nature, undertaken from Linné to Buffon and from Lamarck to Darwin (that is to say, from the belief in the fixity of creation to evolutionism), engendered an entire scientific vocabulary, expressed in terms of kingdoms, classes, types, and species26. Natural history, from the Age of Enlightenment on into the nineteenth century, served as a referent for constructing modes of thinking that took into account the physiological and civilisational diversity of the world’s societies. Yet, depending on whether we refer to nomenclatures based on the theory of the fixity of species or, conversely, the dynamics of evolution, the effects of the natural history model upon the social sciences have been quite different. Thus, the intellectual discussion conducted between these two poles of knowledge production (starting with Linné’s Systema Naturae) has contributed to the ambivalence of racial theories of humanity – caught between the theory of fixity (for instance, the impossibility of making people reform to adhere to a model that is not native to them) and the fear of degeneration caused by mixed marriages and their resulting spawn27. During the second half of the nineteenth century and the first of the twentieth, the societies of the American hemisphere offered an observatory for the complete range of these possibilities. On the one hand, laws against any kind of mixed marriage in the United States; on the other, great campaigns aimed at attracting European migrants in the hopes of “improving” and “whitening the race” in a number of Latin American countries28. In the first instance, segregation, whose object was to prevent black elements from infiltrating the constitution of white families; in the second, a call for contributions of white blood, aimed at reducing the dominant Amerindian and African features in societies where Europeans had remained in the minority since the conquest of the Americas.

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie, The danger of a single story (conférence for TED, 2009)

Racial thinking does not, therefore, amount to a choice between the argument of fixity and the dynamic account. What is more, relegation and stigmatisation may be justified by the idea that accidents of existence are able to modify people’s essences in a negative way. This corresponds to a generic belief that has been referred to scientific debate since the mid-nineteenth century as the “inheritance of acquired characteristics”, but which has actually been around for much longer. The notion of congenital inferiority and the natural transmission of the condition of slavery, for example, belong to this system. In fact, the theory of the historic transmutation of peoples – towards their increasing inferiority – is equally possible; this was the case for the Jewish people (or the Hebrews, if you will), whose nature was held to have metamorphosed after they refused to join the new covenant following the death and the resurrection of Jesus Christ29. Due to their blindness, the Jews were deemed to have passed from the highest rung of the hierarchy of peoples to the most deplorable condition.

The contradiction between fixity and metamorphosis is manifested in many ways. For example, the aristocracy holds nobility to be a timeless condition. Nonetheless, royal ideologies maintain that certain types of activities can confer nobility. Belonging to a good lineage ensures the ability to exert worthy roles, and vice versa – and both are guaranteed and reinforced by the congenital transmission of virtues and the assurance of recognition by the royal institution. But theories of nobility must contend with the mystery of the entrance into nobility – in other words, they must respond to the following insoluble question: are those who are raised to the nobility by the will of the king not already recognised as such? Royal grace is the agent of a mutation, a change in nature – a miracle. It is plain to see here how three partly contradictory mechanisms compete to forge the ideology of noble domination: the perpetuity of lineage; the fulfilment of gestures attesting to one’s noble condition; the almost thaumaturgical exercises of a king who “makes” nobles. In the end, the natural fixity of conditions, the inheritance of acquired characteristics, and the belief in the effects of transmutation combine and become good bedfellows in the political ideologies of the modern age.

Universalisms and Racisms

In studies of societies of the late Middle Ages and the modern era, the question arises of the incompatibility of the message of Saint Paul (“There is neither Jew or Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male or female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus”, Galations 3:28) and the efficacy of grace (“If you belong to Christ, then you are Abraham’s seed, and heirs according to the promise”, Galatians 3:29) with the rules of segregation, based on natural inferiority and people’s ineptitude to change. The persecution of the descendants of converts in Iberian societies at the end of the Middle Ages and under the Ancien Régime stands as a negation of these principles. By decreeing that the descendants of converted Jews or Muslims were to remain under suspicion and were doubtless the bearers of threats to society, the Iberian courts and the laws of blood purity belied the efficacy of baptism30. Everything went ahead as if baptismal water was powerless to wash away lowly blood.

Rather than being one among many others, the case of converted Jews in the Iberian Peninsula can be understood as the earliest form of modern racism. Indeed, at the end of the Middle Ages, the Jewish society of Spain and Portugal was by far the largest of its kind in Europe, and even in the Mediterranean basin. Yet urban and rural coexistence with the Christian majority had led to a context in which, notwithstanding the ritual acts of religious life, it was difficult to distinguish a Jew from a Christian at first sight. From the thirteenth century onwards (the Fourth Council of the Lateran, 1215), the dread of sexual relations between Jews and Christians had resulted in Jews being obligated to carry a distinctive mark on their clothing31: a sign (if ever there was) of the invisibility of Jews. The feeling that the confusion between Jews and Christians represented a spiritual and social danger only worsened when – under duress or of their own accord – Jews began to convert en masse, notably after a series of very violent pogroms (1391-1392)32. From then on, those Jews – who were no longer Jews – became doubly invisible. The question arose too, albeit in a different way, for the minority of Muslims who were forced to convert: the Moriscos33. Once again there flourished the idea that – despite social appearances – their lowly origin was transmitted by some deep nature, of which blood was the vector. This is precisely the model for the process of “alteration” by which racial thinking transforms the same into the other34. This pattern can be found at the heart of the political machinations used by the Spanish and Portuguese conquistadors in the construction of their transcontinental empires.

« Pretoria has been made by the White mind for the White man. We are not obliged even the least to try to prove to anybody and to the Blacks that we are superior people. We have demonstrated that to the Blacks in a thousand and one ways. […] We do not pretend like other Whites that we like Blacks. The fact that, Blacks look like human beings and act like human beings do not necessarily make them sensible human beings. […] Hedgehogs are not porcupines and lizards are not crocodiles simply because they look alike. If God wanted us to be equal to the Blacks, he would have created us all of a uniform colour and intellect. But he created us differently: Whites, Blacks, Yellow, Rulers and the ruled. Intellectually, we are superior to the Blacks; that has been proven beyond any reasonable doubt over the years. »

The former South African President P. W. Botha to his Cabinet, 16 August 1985.

The former South African President P. W. Botha (1916-2006)

The antinomy of universalism and racism is not exclusive to Christianity. Islam is permeated by just as powerful a contradiction, and in terms that are not so different. Studies of medieval theological and juridical corpuses have even shown that the societies that forged the first operational version of the myth of Ham, to justify the enslavement of black people, were those of medieval Islam35. This myth refers to an episode from Genesis (9:18-29), in which Ham (the son of Noah) sees his father naked while drunk. Upon awakening, Noah condemns Ham, as well as his descendants, to perpetual servitude. Certain Old Testament scholars have interpreted this curse as being addressed at black skinned people. This version of the story remains almost absent from the medieval rabbinical tradition36. However, it occupies an important place as part of the first centuries of Islamic tradition. The chronological antecedence of slave raiding practices against sub-Saharan populations by Islamic powers, and the presence of slave markets in Muslim Spain: these are two legacies that Christian Europe received from Mediterranean Islam. By the Middle Ages, various European languages had abandoned the Latin term servus, in favour of the word “slave”, meaning Slav. This reflected the existence of a market for servile manpower that was drawn from the Balkan societies. The convergence of slave status and blackness in European countries was both an import from the Muslim world and a belated reality37. The myth of Noah’s curse upon blacks was reactivated, with extreme virulence and brutality, in the context of American responses to abolitionist campaigns, notably during the Antebellum Period and the Civil War. At this time, propaganda in favour of the maintenance of the slave system of production ran riot and spread a breviary of the hatred of black people across both the United States and Europe. It is on this mass of texts, pamphlets and images that racist leagues and associations have drawn since the end of the slavery regime until the present day. The same occurred in Cuba, with press campaigns and violent outbursts targeting political organisations of black ex-combatants from the War of Independence, at the time of the “Independents of Colour” massacre in 191238.

The antinomy of universalism and racism remains unresolved in the contemporary era. This is testified to, for example, by the French Republic’s difficulty to integrate not only “indigenes” of its colonial Empire, but also the children of couples formed by a European and an indigene as full citizens39. The principle of universal citizenship in the French political sphere stumbled against this obstacle right until the empire’s dismantlement. Another example of this antinomy is the acceptance of social Darwinism by Christian ideologues in Europe during the second half of the nineteenth and the first half of the twentieth century40. In Weimar Germany, Wilhelm Schmidt – a Catholic priest holding the title of chair of ethnology at the University of Vienna – became the director of the department of eugenics at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity and Eugenics in Berlin between 1927 and 193341. Without distancing himself from the monogenesis of official science, this ecclesiast attempted to forge a plausible scenario in which two thousands years of blindness to the evangelical truth – of uprooting, manoeuvring, and concealment – had resulted in racial effects upon Jews: effects so deeply inscribed in their nature that by now not even baptism could correct them42. In fact, it took nothing less than the launching of the Nazi programme to unleash, in retaliation, an international initiative to denounce racial ideologies, developed under the aegis of Unesco in the wake of the collapse of the Third Reich. Racist thought was now condemned for its lack of scientific basis, its proven harmfulness, its incompatibility with the principle of recognition of humankind’s unity – in other words, the universality of human rights.

Scientific Racism and Reductio ad Hitlerum

The choice of the longue durée does not lessen the attention paid to the contemporary period. On the contrary, regardless of their period of study or predilection, all historians approach racial issues while bearing in mind more or less consciously the triad of the Jim Crow laws in the United States, Nazism in Europe, and Apartheid in South Africa. These are the common points of reference for all researchers working on these problems, whether this is recognised explicitly, or whether it remains implicit and sometimes even unconscious. As a good historical method, this triad should avoid being held as the inevitable culmination of a long history whose threads we strive to trace back in time by treading the path in reverse. On the contrary, it is preferable to consider it the point of departure for any reflexive approach to the historical heritage (that is to say the political and intellectual context) that researchers in the humanities and social sciences receive jointly when they commit to studying these questions. When historians of any period compare their field of research to the contemporary triad – in the aim of showing that their case is similar, or, on the contrary, that it differs from it – it is advisable to have an intimate understanding of how contemporary racist politics were put in place and developed. This is why historians of racial issues should be specialists in their period and, at the same time, acquire a reasonable level of information on Jim Crow-Nazism-Apartheid style racisms. This is not always the case.

In the historiography, there is a dominant tendency towards refusing the idea that social hierarchies had a racial dimension, prior to the establishment of contemporary racist regimes. This position leans upon the reference-point and spectre of Nazism. It shelters behind the good sense of refusing a reductio ad Hilterum (to use the expression of Léo Strauss), or rests (as is now said) upon a critique of Godwin’s law43. There seems to arise a syllogism, namely: the case that I study differs from German society of the 1930s-40s; Hitlerism incarnates racism in politics; thus my case does not relate to racism in politics. Yet this type of argument is often nourished by a lack of understanding of Hitler’s regime. For example, from the quills of Anglophone historians one finds the idea that, under the Ancien Régime in Europe and in the colonies, race was not to do with biology but rather with lineage44. Yet, a reading of the Nuremberg Laws regarding the protection of German blood in 1935 shows that the identification of individuals’ Jewish nature also rested upon a logic of lineage. Indeed, in the case of an individual with a Jewish grandparent, the erasure of the Jewish tare in this mixed genealogy would only have been possible if the “Jewish” grandparent had never been affiliated to a synagogue. In fact, civil servants and leaders of the Nazi party had arrived at the conclusion that botanist Gregor Mendel’s laws on the transmission of hereditary traits could not determine whether a “mixed” half-Jew was worthy to join the German people and citizenry, or if he should be forever excluded from it. Only an “examination of the history of his family and his political positions in general” could deliver the pertinent criteria, on a case-by-case basis45. Nonetheless, the Jews in Germany who participated in Jewish life, attended synagogue, were members of associations, and practised intermarriage of course found themselves rejected by the German people. Altogether then, in spite of the rambling broadcasts that drew their vocabulary from the observation of hereditary transmissions, the Nazis targeted their victims according to religious, cultural, political, and lineage-based criteria. For the Nazis, too, race was a question of lineage! From this point of view, Nazi anti-Semitism was also a racism without race, if the term is given a rigorous genetic meaning.

The demonstration in Paris following the death of Adama Traoré, a 24-year-old Frenchman who suffocated after being arrested by gendarmes during an identity check.

The engineering feats that the Nazis put to the service of extermination are by no means an indicator of the scientific or biological character of their interpretation of the world and their racial programme – which, one as much as the other, drew upon an interpretation that was political through and through. The industrial technologies of death were not built upon the natural sciences. If the Nazis consistently failed to define the “Jew” on a genetic scale, it is because the discoveries that enabled the mapping of the human genome were published after the collapse of their regime. We therefore cannot in any way invoke the Nazi case as a touchstone for distinguishing a modern era “proto-racism” from a full racism that supposedly pertains to the contemporary age. Conversely, anthropologist Nancy Farris underlines the fact that what she calls the “physical anthropology” of the twentieth century has taught us that races do not exist. Yet, she continues, this does not authorise us in any way to project this certitude into the pasts of human societies. Nothing justifies the hypothesis that people from earlier periods had acquired, like us today, the conviction that it was absurd to divide (or even to describe) societies by racial categories46.

What differentiated Nazi racial politics (or those of the Jim Crow laws or of South African Apartheid) from earlier forms of discrimination was not the blossoming of a scientific revolution, but rather the consequences of democratic and liberal revolutions with the formation of sovereign nation states; the birth of the national citizen; and the unlimited capacity to mobilise a nationalist ideology – of which there is only one version, equally dangerous everywhere. The cataloguing of the intellectual history of racism within the agreed-upon scenario of the scientific revolution therefore calls for criticism. On the one hand, racial thinking was nourished by a long nineteenth century of regimes of argumentation that owed nothing to the development of observations about the mechanisms of inheritance. Such was the case of the natural role attributed to languages in the formation of the character of peoples47. Such was the case of the historical and philological forgery that was the invention of the Indo-Europeans48. Such was the case of the romantic elevation of Migration Period art in contrast to the ostensible incapacity of Jews to achieve such feats49. Such was the case of the discourse of justification and continuation of the nineteenth century colonial enterprises, which rested (as during the Ancien Régime) upon the argument of civilisation within an evolutionist framework, with no real place for genetic concepts – even when this meant excluding mixed individuals from citizenship. The history of the world through the evolution of its races that was sketched out by Gobineau in his Essay on the Inequality of Human Races (1853) was a lament on the decline of the aristocratic principle, which had very little to do with the medical knowledge of his time. Certainly, the eugenic programmes of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries forged an imaginary of inheritance and donned their white laboratory coats – but the social engineering that they promoted did not differ radically from the old segregationist or genocidal programmes, which never gave rise to experiments on inheritance50. In other words, modern racism is only modern in a political sense, because its national character instils it with a new energy. But it is not supported by scientific modernity. At the same time, it is hard to see what we gain by opposing it to an Ancien Régime “proto-racism” that is reputedly archaic – or, to put it another way, less scientific.

Notes

1

Ania Loomba, “Race and the Possibilities of Comparative Critique”, New Literary History, vol. 40, 2009, p. 501-522.

2

Magali Bessone, Sans distinction de race ? Une analyse critique du concept de race et de ses effets pratiques, Paris, Vrin, 2013.

3

Albert Jacquard, “À la recherche d’un contenu pour le mot ‘race’. La réponse du généticien”, in M. Olender (ed.), Pour Léon Poliakov. Le racisme mythes et sciences, Bruxelles, Éditions Complexe, 1981, p. 31-40; François Jacob, “Biologie et racisme” in La science face au racisme [1981], Le genre humain, n° 1, 2008.

4

Catherine Bliss, Race Decoded. The Genomic Fight for Social Justice, Stanford, Stanford University Press, 2012; Katharina Schramm, David Skinner, Richard Rottenburg (ed.), Identity Politics and the New Genetics, New York-Oxford, Bergahn Books, 2012.

5

Gérard Lenclud, L’Universalisme ou le pari de la raison. Anthropologie, histoire, psychologie, Paris, EHESS-Le Seuil-Gallimard, coll. “Hautes études”, Paris, 2013.

6

Alain Blum, “Resistance to identity categorization in France”, in D. I. Ketzner, D. Arel (ed.), Census and Identity. The Politics of Race, Ethnicity, and Language in National Censuses, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2004, p. 121-147; Gwénaële Calvès, “‘Il n'y pas de race ici’. Le modèle français à l'épreuve de l'intégration européenne”, Critique internationale, n° 17, 2002, p. 173-186.

7

Margo J. Anderson, Stephen E. Fienberg, Who Counts ? The Politics of Census-Taking in Contemporary America, New York, Russell Sage Foundation, 2001; Daniel Sabbagh, “Discrimination positive et déségrégation les catégories opératoires des politiques d'intégration aux États-Unis”, Sociétés contemporaines, n° 53, 2004, p. 85-99; Lilia Moritz Schwarcz, Nem preto nem branco, muito pelo contrário: cor e raça na sociabilidade brasileira, São Paulo, Companhia das Letras-Claro Enigma, 2012.

8

See Nonna Mayer’s analysis for La Vie des idées.

9

Michael James, “Race”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Winter 2012 Edition.

10

Sylvia-Lise Bada, “De l’(in)opportunité de la proposition de loi visant à la suppression du mot ‘race’ de notre législation”, Letter “Actualités Droits-Libertés” from CREDOF, 7 June 2013.

11

Christophe Cusset, Gérard Salamon, À la rencontre de l’étranger. L’image de l’Autre chez les Anciens, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 2008 ; Miriam Eliav–Feldon, Benjamin H. Isaac, Joseph Ziegler (ed.), The Origins of Racism in the West, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

12

François Hartog, Le Miroir d’Hérodote [1980], Paris, Gallimard, 2001.

13

Niall McKeown, “Seeing Things: Examining the Body of the Slave in Greek Medicine”, Slavery & Abolition, vol. 23, n° 2, 2002, p. 29-40.

14

Marshall Sahlins, Critique de la sociobiologie. Aspects anthropologiques, Paris, Gallimard, 1980.

15

Timothy Lockley, “Race and Slavery”, in R. L. Paquette, M. Smith (eds.), Oxford Handbook of Slavery in the Americas, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 336-356.

16

Winthrop D. Jordan, White over Black. American Attitudes toward the Negro, 1550-1812, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1968.

17

Eric Williams, Capitalism and Slavery, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1944; Barbara Jeanne Fields, “Slavery, Race and Ideology in the United States of America”, New Left Review, n° 181, 1990, p. 95-118.

18

Giuliano Gliozzi, Adam et le Nouveau Monde. La naissance de l’anthropologie comme idéologie coloniale : des généalogies bibliques aux théories raciales (1500-1700) [1977], Paris, Théétète éditions, 2000.

19

Georges Balandier, “La situation coloniale : approche théorique”, Cahiers Internationaux de Sociologie, vol. XI, 1951, p. 44-79.

20

Rees R. Davies, Domination and Conquest. The Experience of Ireland, Scotland and Wales 1100-1300, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1990; Nicholas Canny, Making Ireland British, 1580-1650, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2001.

21

Frantz Fanon, Peau noire, masques blancs [1952], in F. Fanon, Œuvres, Paris, La Découverte, 2012; Albert Memmi, Portrait du colonisé, précédé du portrait du colonisateur, Paris, Buchet-Chastel, 1957.

22

Rolena Adorno, Guaman Poma. Writing and Resistance in Colonial Peru, Austin, University of Texas Press, 2000; Alfredo Alberdi Vallejo, El mundo al revés. Guamán Poma anticolonialista, Berlin, Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, 2010.

23

Charles de Miramon, “Noble dogs, noble blood : the invention of the concept of race in the late Middle Ages”, in M. Eliav-Feldon, B. H. Isaac, J. Ziegler (eds.), The Origins of Racism in the West, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2009, p. 200-216.

24

Pierre Savy, “Transmission, identité, corruption. Réflexions sur trois cas d'hypodescendance”, L'Homme, n° 182, 2007, p. 53-80.

25

Silvia Sebastiani, The Scottish Enlightenment. Race, Gender, and the Limits of Progress, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

26

Lisbet Koerner, Linnaeus. Nature and Nation, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1999 ; Pietro Corsi, Lamarck. Genèse et enjeux du transformisme, 1770-1830, Paris, CNRS Éditions, 2001 ; Thierry Hoquet, Buffon. Histoire naturelle et philosophie, Paris, Honoré Champion, 2005.

27

Peggy Pascoe, What comes naturally. Miscigenation Law and the making of Race in America, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2010.

28

Lilia Moritz Schwarcz, O espetáculo das raças. Cientistas, instituições e pensamento racial no Brasil : 1870-1930, São Paulo, Companhia das Letras, 1993.

29

Denise Kimber Buell, Pourquoi cette race nouvelle ? Le raisonnement ethnique dans le christianisme des premiers siècles, Paris, Le Cerf, 2012.

30

Bernard Vincent, “Les Morisques grenadins : une frontière intérieure ?”, Castrum, 4, 1992, p. 109-126; Isabelle Poutrin, Convertir les musulmans. Espagne, 1491-1609, Paris, PUF, 2012; Max S. Hering Torres, “Limpieza de sangre en España. Un modelo de interpretación”, in N. Böttcher, B. Hausberger, M. S. Hering Torres (ed.), El peso de la sangre. Limpios, mestizos y nobles en el mundo hispánico, Mexico, El Colegio de México, 2011, p. 29-62.

31

Maurice Kriegel, “Un trait de psychologie sociale dans les pays méditerranéens du bas Moyen Âge : les juifs comme intouchables”, Annales E.S.C., 31e année, n° 2, 1976, p. 326-330; Maurice Kriegel, Les Juifs à la fin du Moyen Âge dans l’Europe méditerranéenne, Paris, Hachette Littérature, 1979.

32

David Nirenberg, “The case of Spain and its Jews”, in M. R. Greer, W. D. Mignolo, M. Quilligan (eds.), Rereading the Black Legend. The Discourses of Religious and Racial Difference in the Renaissance Empires, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 2007, p. 71-87.

33

Bernard Vincent, “¿Cuál era el aspecto físico de los Moriscos?”, in Andalucía en la Edad Moderna: economía y sociedad, Diputación Provincial de Granada, Granada, 1985, p. 303-313.

34

Claude-Olivier Doron, Races et dégénérescence. L’émergence des savoirs sur l’homme anormal, doctoral thesis in philosophy, Université Paris-Diderot, 2011.

35

Benjamin Braude, “Cham et Noé. Race, esclavage et exégèse entre islam, judaïsme et christianisme”, Annales. HSS, 57e année, n° 1, 2002, p. 93-125.

36

David H. Aaron, “Early Rabbinic Exegesis on Noah’s Son Ham and the So-Called ‘Hamitic Myth’”, Journal of the American Academy of Religion, vol. 63, n° 4, 1995, p. 721-759.

37

George M. Fredrikson, The Black Image in the White Mind. The Debate on Afro-American Character and Destiny, 1817-1914, Hanover (NH), Wesleyean University Press, 1971, p. 58-64, 87-88; Andrew S. Curran, The Anatomy of Blackness. Science and Slavery in an Age of Enlightenment, Baltimore, John Hopkins University Press, 2011.

38

Silvio Castro Fernández, La masacre de los Independientes de Color en 1912, Havana, Ciencias Sociales, 2002 ; Marial Iglesias Utset, “Los Despaigne en Saint-Domingue y Cuba: narrativa microhistórica de una experiencia atlántica”, Revista de Indias, vol. 71, n° 251, 2011, p. 77-107.

39

Emmanuelle Saada, Les Enfants de la colonie. Les métis de l'Empire français entre sujétion et citoyenneté, Paris, La Découverte, 2007; Silvia Falconieri, Florence Renucci, “L’Autre et la littérature juridique : Juifs et indigènes dans les manuels de droit (xixe-xxe siècles)”, in A.-S. Chambost (ed.), Des traités aux manuels de droit. Une histoire de la littérature juridique comme forme du discours universitaire, Paris, Lextenso, 2014, p. 253-274.

40

André Pichot, Aux origines des théories raciales de la Bible à Darwin, Paris, Flammarion, 2008, p. 328-349.

41

Paul Weindling, “Weimar Eugenics: The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics in Social Context”, Annals of Science, vol. 42, 1985, p. 303-318.

42

John Connelly, From Enemy to Brother. The Revolution in Catholic Teaching on the Jews, 1933-1965, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2012, p. 17.

43

Léo Strauss, Droit naturel et histoire [1953], Paris, Flammarion, 2008, chap. II; François de Smet, Reductio ad hitlerum. Une théorie du point Godwin, Paris, PUF, 2014.

44

Michael Banton, Racial Theories, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1987, p. 17-43.

45

Edouard Conte, Cornelia Essner, La Quête de la race. Une anthropologie du nazisme, Paris, Hachette, 1995, p. 224.

46

Nancy Farris, Maya Society Under Colonial Rule. The Collective Enterprise of Survival, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1984, p. 102.

47

Maurice Olender, Les Langues du Paradis. Aryens et Sémites : un couple providentiel, Paris, Le Seuil, 1989.

48

Jean-Paul Demoule, Mais où sont passés les Indo-Européens ? Le mythe d’origine de l'Occident, Paris, Le Seuil, 2014.

49

Éric Michaud, Les Invasions barbares. Une généalogie de l’histoire de l’art, Paris, Gallimard, 2015.

50

André Pichot, La Société pure. De Darwin à Hitler, Paris, Flammarion, 2000; Pierre-André Taguieff, La Couleur et le sang. Doctrines racistes à la française, Paris, Mille et une nuits, 2002.

Bibliographie

David H. Aaron, “Early Rabbinic Exegesis on Noah’s Son Ham and the So-Called 'Hamitic Myth'”, Journal of the American Academy of Religion, vol. 63, n° 4, 1995, p. 721-759.

Rolena Adorno, Guaman Poma. Writing and Resistance in Colonial Peru, Austin, University of Texas Press, 2000.

Alfredo Alberdi Vallejo, El mundo al revés. Guamán Poma anticolonialista, Berlin, Wissenschaftlicher Verlag, 2010.

Margo J. Anderson, Stephen E. Fienberg, Who Counts? The Politics of Census-Taking in Contemporary America, New York, Russell Sage Foundation, 2001.

Sylvia-Lise Bada, “De l’(in)opportunité de la proposition de loi visant à la suppression du mot 'race' de notre législation, Lettre “Actualités Droits-Libertés” du CREDOF, 7 juin 2013.

Georges Balandier, “La situation coloniale: approche théorique”, Cahiers Internationaux de Sociologie, vol. XI, 1951, p. 44-79.

Michael Banton, Racial Theories, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1987.

Magali Bessone, Sans distinction de race? Une analyse critique du concept de race et de ses effets pratiques, Paris, Vrin, 2013.

“Catherine Bliss, Race Decoded. The Genomic Fight for Social Justice, Stanford, Stanford University Press, 2012.

Alain Blum, Resistance to identity categorization in France”, in D. I. Ketzner, D. Arel (dir.), Census and Identity. The Politics of Race, Ethnicity, and Language in National Censuses, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2004, p. 121-147.

Benjamin Braude, “Cham et Noé. Race, esclavage et exégèse entre islam, judaïsme et christianisme”, Annales. HSS, 57e année, n° 1, 2002, p. 93-125.

Gwénaële Calvès, “‘Il n'y pas de race ici’. Le modèle français à l'épreuve de l'intégration européenne”, Critique internationale, n° 17, 2002, p. 173-186.

Nicholas Canny, Making Ireland British, 1580-1650, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2001.

Silvio Castro Fernández, La masacre de los Independientes de Color en 1912, La Havane, Ciencias Sociales, 2002.

John Connelly, From Enemy to Brother. The Revolution in Catholic Teaching on the Jews, 1933-1965, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2012.

Edouard Conte, Cornelia Essner, La Quête de la race. Une anthropologie du nazisme, Paris, Hachette, 1995.

Pietro Corsi, Lamarck. Genèse et enjeux du transformisme, 1770-1830, Paris, CNRS Éditions, 2001.

Andrew S. Curran, The Anatomy of Blackness. Science and Slavery in an Age of Enlightenment, Baltimore, John Hopkins University Press, 2011.

Christophe Cusset, Gérard Salamon, À la rencontre de l’étranger. L’image de l’Autre chez les Anciens, Paris, Les Belles Lettres, 2008.

Rees R. Davies, Domination and Conquest. The Experience of Ireland, Scotland and Walles 1100-1300, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1990.

Jean-Paul Demoule, Mais où sont passés les Indo-Européens? Le mythe d’origine de l'Occident, Paris, Le Seuil, 2014.

Claude-Olivier Doron, Races et dégénérescence. L’émergence des savoirs sur l’homme anormal, thèse de doctorat en philosophie, Université Paris-Diderot, 2011.

Miriam Eliav-Feldon, Benjamin H. Isaac, Joseph Ziegler (dir.), The Origins of Racism in the West, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Frantz Fanon, Peau noire, masques blancs [1952], in F. Fanon, Œuvres, Paris, La Découverte, 2012.

Barbara Jeanne Fields, Slavery, “Race and Ideology in the United States of America”, New Left Review, n° 181, 1990, p. 95-118.

Silvia Falconieri, Florence Renucci, “L’Autre et la littérature juridique: Juifs et indigènes dans les manuels de droit (XIXe-XXe siècles)”, in A.-S. Chambost (dir.), Des traités aux manuels de droit. Une histoire de la littérature juridique comme forme du discours universitaire, Paris, Lextenso, 2014, p. 253-274.

Nancy Farris, Maya Society Under Colonial Rule. The Collective Enterprise of Survival, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1984.

George M. Fredrikson, The Black Image in the White Mind. The Debate on Afro-American Character and Destiny, 1817-1914, Hanover (NH), Wesleyean University Press, 1971.

Giuliano Gliozzi, Adam et le Nouveau Monde. La naissance de l’anthropologie comme idéologie coloniale : des généalogies bibliques aux théories raciales (1500-1700) [1977], Paris, Théétète éditions, 2000.

François Hartog, Le Miroir d’Hérodote [1980], Paris, Gallimard, 2001.

Max S. Hering Torres, “Limpieza de sangre en España. Un modelo de interpretación”, in N. Böttcher, B. Hausberger, M. S. Hering Torres (dir), El peso de la sangre. Limpios, mestizos y nobles en el mundo hispánico, Mexico, El Colegio de México, 2011, p. 29-62.

Thierry Hoquet, Buffon. Histoire naturelle et philosophie, Paris, Honoré Champion, 2005.

François Jacob, “Biologie et racisme”, in La science face au racisme [1981], Le Genre humain, n° 1, 2008.

Albert Jacquard, “À la recherche d’un contenu pour le mot 'race'. La réponse du généticien”, in M. Olender (dir.), Pour Léon Poliakov. Le racisme mythes et sciences, Bruxelles, Éditions Complexe, 1981, p. 31-40.

Michael James, “Race”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Winter 2012 Edition.

Winthrop D. Jordan, White over Black. American Attitudes toward the Negro, 1550-1812, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1968.

Denise Kimber Buell, Pourquoi cette race nouvelle? Le raisonnement ethnique dans le christianisme des premiers siècles, Paris, Le Cerf, 2012.

Lisbet Koerner, Linnaeus. Nature and Nation, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1999.

Maurice Kriegel, “Un trait de psychologie sociale dans les pays méditerranéens du bas Moyen Âge: les juifs comme intouchables”, Annales E.S.C., 31e année, n° 2, 1976, p. 326-330.

Maurice Kriegel, Les Juifs à la fin du Moyen Âge dans l’Europe méditerranéenne, Paris, Hachette Littérature, 1979.

Gérard Lenclud, L’Universalisme ou le pari de la raison. Anthropologie, histoire, psychologie, Paris, EHESS-Le Seuil-Gallimard, Paris, 2013.

Timothy Lockley, “Race and Slavery”, in R. L. Paquette, M. Smith (dir.), Oxford Handbook of Slavery in the Americas, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2010, p. 336-356.

Ania Loomba, “Race and the Possibilities of Comparative Critique”, New Literary History, vol. 40, 2009, p. 501-522.

Nonna Mayer, “Le mythe de la dédiabolisation du Front National”, La Vie des idées, 2015.

Niall McKeown, “Seeing Things: Examining the Body of the Slave in Greek Medicine”, Slavery & Abolition, vol. 23, n° 2, 2002, p. 29-40.

Albert Memmi, Portrait du colonisé, précédé du portrait du colonisateur, Paris, Buchet-Chastel, 1957.

Éric Michaud, Les Invasions barbares. Une généalogie de l’histoire de l’art, Paris, Gallimard, 2015.

Charles de Miramon, “Noble dogs, noble blood: the invention of the concept of race in the late Middle Ages”, in M. Eliav-Feldon, B. H. Isaac, J. Ziegler (dir.), The Origins of Racism in the West, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2009, p. 200-216.

Lilia Moritz Schwarcz, O espetáculo das raças. Cientistas, instituições e pensamento racial no Brasil, 1870-1930, São Paulo, Companhia das Letras, 1993.

Lilia Moritz Schwarcz, Nem preto nem branco, muito pelo contrário: cor e raça na sociabilidade brasileira, São Paulo, Companhia das Letras-Claro Enigma, 2012.

David Nirenberg, “The case of Spain and its Jews”, in M. R. Greer, W. D. Mignolo, M. Quilligan (dir.), Rereading the Black Legend. The Discourses of Religious and Racial Difference in the Renaissance Empires, Chicago, The University of Chicago Press, 2007, p. 71-87.

Maurice Olender, Les Langues du Paradis. Aryens et Sémites: un couple providentiel, Paris, Le Seuil, 1989.

Peggy Pascoe, What comes naturally. Miscigenation Law and the making of Race in America, Oxford, Oxford University Press, 2010.

André Pichot, La Société pure. De Darwin à Hitler, Paris, Flammarion, 2000.

André Pichot, Aux origines des théories raciales de la Bible à Darwin, Paris, Flammarion, 2008.

Isabelle Poutrin, Convertir les musulmans. Espagne, 1491-1609, Paris, PUF, 2012.

Emmanuelle Saada, Les Enfants de la colonie. Les métis de l'Empire français entre sujétion et citoyenneté, Paris, La Découverte, 2007.

Daniel Sabbagh, “Discrimination positive et déségrégation les catégories opératoires des politiques d'intégration aux États-Unis”, Sociétés contemporaines, n° 53, 2004, p. 85-99.

Marshall Sahlins, Critique de la sociobiologie. Aspects anthropologiques, Paris, Gallimard, 1980.

Pierre Savy, “Transmission, identité, corruption. Réflexions sur trois cas d’hypodescendance”, L'Homme, n° 182, 2007, p. 53-80.

Katharina Schramm, David Skinner, Richard Rottenburg (dir.), Identity Politics and the New Genetics, New York-Oxford, Bergahn Books, 2012.

Silvia Sebastiani, The Scottish Enlightenment. Race, Gender, and the Limits of Progress, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2013.

François de Smet, Reductio ad hitlerum. Une théorie du point Godwin, Paris, PUF, 2014.

Léo Strauss, Droit naturel et histoire [1953], Paris, Flammarion, 2008.

Pierre-André Taguieff, La Couleur et le sang. Doctrines racistes à la française, Paris, Mille et une nuits, 2002

Marial Iglesias Utset, “Los Despaigne en Saint-Domingue y Cuba: narrativa microhistórica de una experiencia atlántica”, Revista de Indias, vol. 71, n° 251, 2011, p. 77-107.

Bernard Vincent, “Les Morisques grenadins: une frontière intérieure?”, Castrum, 4, 1992, p. 109-126.

Bernard Vincent, “¿Cuál era el aspecto físico de los Moriscos?”, in Andalucía en la Edad Moderna: economía y sociedad, Diputación Provincial de Granada, Granada, 1985, p. 303-313.

Paul Weindling, “Weimar Eugenics: The Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics in Social Context”, Annals of Science, vol. 42, 1985, p. 303-318.

Eric Williams, Capitalism and Slavery, Chapel Hill, University of North Carolina Press, 1944.