The notion of notable has occupied an essential place in the social history of politics in contemporary France1. It was used to characterize the nineteenth century ruling élites, understood as a small group of individuals and family lineages endowed simultaneously with economic wealth (mainly land), social prestige and political power. The aim was to describe the formation, in the aftermath of the French Revolution, of a social milieu in which the nobility retained a dominant, but not exclusive position: its members mixed with the well-off portions of the landowning bourgeoisie with whom from then on they shared the monopoly of access to elected offices and administrative functions – whether the monopoly was assured by law (by census) or de facto (as in the oligarchies of the Second Empire). “The end of notables” would thus correspond to a democratization process, which in fact was only fully achieved after the establishment of the Third Republic in 1870. In short, “notables” appear to be the protagonists during a transitional era between a society of orders that prolonged the Ancien Regime and a political modernity of which they were one of the antithetical figures.

The advantage of limiting the notion of notable in this way, to a circumscribed social group (censitaire elites) and a particular historical period (preceding the durable establishment of the Republic), is that of avoiding a potentially inexact usage2. Indeed, despite the diverse situations and hierarchical ranks it embraced, the notable class was a relatively coherent group due to its attributes and privileges (wealth in terms of land, active citizenship, exercise of public function), and its way of life (sociability and worldly obligations, participation in community life, philanthropy, etc.).

This intentionally restrictive concept is consistent with an interpretative approach to the Republicanizing of French society which – by associating it with the replacement of former nobility élites by professionalized politicians from intermediate social categories (small landowners, civil servants, professionals) that began in the last quarter of the nineteenth century – stresses the upheaval caused by the anchoring of universal suffrage However, such a clear opposition between the nobility model and the democratic model tends to rule out taking into account certain attested forms of the continuity of the nobility's power far beyond the period of the establishment of the Republic – that is to say, other than in the residual form of a permanence of the past which disappeared with the professionalization of politics, the specialization of the administrative tasks of elected representatives and the development of organized political parties.

Le Vote universel 10 Décembre 1848 (estampe, 1848).

Both recent social history of the Third Republic and the sociology of local power in France3 have laid emphasis on this continuity, giving rise to a review of the “end of the notables” hypothesis. Thus the need to examine how notable practices (clientelism, the constitution and maintenance of a personalized and territorialized patrimony, the mediation between local space and the political-administrative authorities) evolved both within former elites converted to the Republic and in the new professionalized political class; in other words, how these practices adapted themselves to changes in electoral competition, public action and the day-to-day work of an elected deputy. In so doing, our interest focuses less on notables as a pre-determined group, and more on ways of becoming a notable, less on specific historical situations in which this group came about and exercised its hegemony, and more on practices of power that the notion of notable enables us to recognize in very different sociopolitical contexts4.

Historiography of democratic politicization

The historiography of democratic politicization in France classically refers to an interpretive explanation identifying it with a process of learning and assimilating the ways of the “Republican model” on the part of the population, in particular the rural population. The work of Maurice Agulhon, in which the “introduction of politics in rural areas”5is one of the key factors in the establishment of the Republic, is a typical example of this. Chronology of course varies depending on contexts – it took place later in Western regions, where the influence of the clergy and big landowners often remained strong until the early twentieth century, and earlier in areas with small peasant properties in the Center and South of France.

In the South, the decline of the spiritual hold of the Church, the broadening of the cultural horizon of the masses (thanks to the spread of the national language, increased literacy and reading of the press), the vitality of popular sociability and entities structuring rural life (brotherhoods and fraternities, aid societies, circles and chambers), as of the 1830s favored the “descent of politics towards the masses”. Gradually, populations learned to become interested in public affairs, began to express collectively some of their aspirations (communal use of the land, tax protests, desires for emancipation), and abandoned their traditional tutelary authorities in favor of new leaders – small independent landowners, craftsmen and shopkeepers who took part in the growth of the democratic idea in large portions of the population and with whom they enjoyed more egalitarian forms of social relations6.

As in numerous other regions in France, the presence of politics in rural life and the democratic patronage of new intermediary elites lay the foundations for a rural democracy that made a brief appearance with the first elections by universal male suffrage under the Second Republic (1842-1852), before being crushed during the Second Empire (1852-1870) by the authoritarian control of the vote and repression of opposition, and was consecrated only in the Third Republic. This marked the achievement of a long process of politicization of the rural populations to which the Third Republic contributed by integrating greater numbers of those populations into national political life and spreading democratic politics to rural areas.

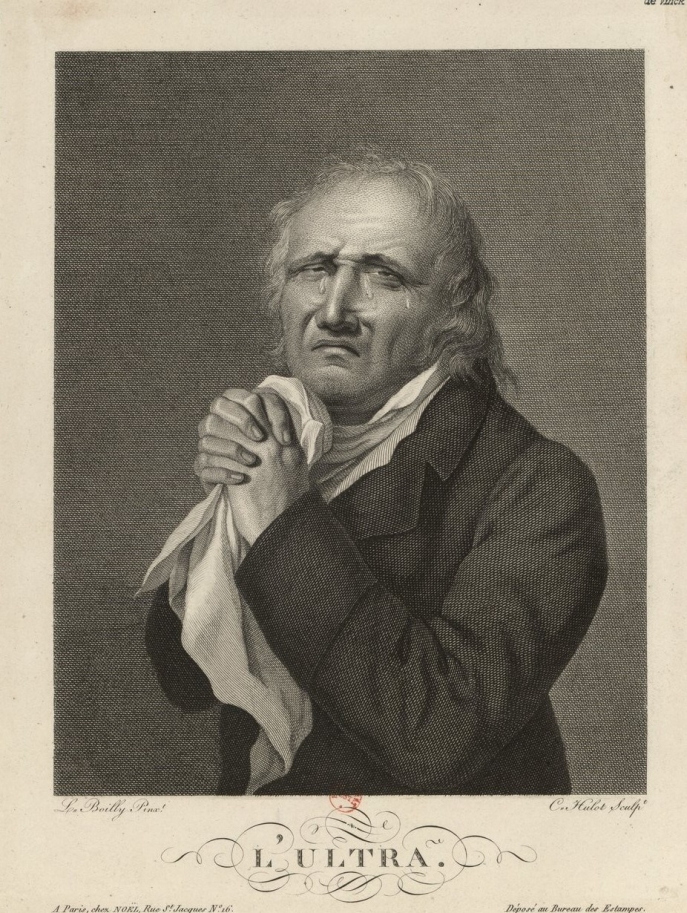

“L'Ultra à mi-corps, pleure sa défaite aux élections d'octobre 1818 et le triomphe du parti libéral” (print, 1818).

These phenomena are sufficiently well known not to need a detailed review7. The regularity of national and local elections, combined with elections that became more and more competitive, put politics into the everyday life of the individual. Citizenship became a concrete experience as people became accustomed to voting as a new mode of expression and realized their potential influence, however minimal, on their representatives, thanks to whom and to the expansion of the press, they became familiar with ideologies and programs of overall interest and took on collective identities (Republicans vs. Monarchists, radicals vs. conservatives, “reds” vs. “whites”) strengthened by vertical relations with elected representatives as well as horizontal ties of solidarity within community or professional networks of sociability and cooperation. The development of civic socialization entities such as compulsory primary school and a conscription army strengthened allegiance to the State and Nation by inculcating abstract principles of citizenship. This contributed to the growth of a national identity based on secularism and Republican morality and was supported by public rituals – celebrations and commemorations – establishing a collective social link with a symbolic basis common to all.

“La loi des élections est accouchée heureusement d'un enfant marqué sur le front d'un grand R et de taches de sang sur les mains” (print, 1819).

In this way, citizens learned to link local events to political issues debated nationally and took on roles in civilian life that led them to become interested in public affairs and aware of outside political influences. The origin of these processes was not new, as shown by several studies pointing out the major role that the broadening of local suffrage under the July Monarchy played in raising rural populations' political awareness and citizenship learning (notably with the law of 21 March 1831 that gave close to a third of the male population of voting age the possibility to elect municipal councilors)8. However, there has been considerable controversy over how much raising of awareness there actually was and how the learning took place. Those who defend the thesis of early politicization thanks to democratic permeation of rural social structures and ways of thinking are opposed to those who, like Eugen Weber, underscore the persistence of an “archaic stage” of political life in many French regions up to the eve of World War I – that is, before peasant communities broke out of their isolation, before the effects of education and economic modernization were felt and before “individuals and groups shifted from indifference to participation because that perceived that they were involved in the nation”9.

Alexis-Charles-Henri Cléral de Tocqueville, by Théodore Chasseriau (1850).

However in both cases, politicization was the result of integration into national space and education in democracy, first under the auspices of the emerging progressive elites and then under those of the Republican State10.

The Republic and the “end of the notables”

Democratic politicization tends to be represented as the extinction of the former powers of the nobles. Echoing an opinion widespread among Republican elites of the time – and passionately formulated by Leon Gambetta heralding the coming to power, with the Republic, of a new political personnel from the “new social classes”11– a number of historians have associated the advent and anchoring of the Third Republic with the “end of the notables”.

Maurice Agulhon, for example, writes, “Emancipated from the traditional “great men” and from priests, the Republican peasant believed in new leaders in the middle-class Republican bourgeoisie of doctors, men of law, professors, merchants, and small manufacturers who evicted the marquis and master forgers”12. Jean-Marie Mayeur, among others, echoes this approach: “in less than a decade [between1871 and 1879], a new personnel having arrived by universal suffrage established itself at the wheel.” Replacing the nobility, the former bourgeoisie and rural landowners, “lawyers, doctors and professors took their revenge on the conservative society of the town seat. From then on, they provided a structure for the people, from whom they wished to distinguish themselves, but whose aspirations they knew how to satisfy much better than the conservative 'Messieurs'”13.

These of course are simplifications, nuanced by the authors themselves, Algulhon claiming they are only “partial” tendencies, Mayeur underscoring the social diversity of the Republic’s elites, who were joined by parts of the upper bourgeoisie and high administration. The percentage of nobility holding municipal elected offices, for example, began to decline in the 1830s, when the share of mayors from the liberal and legal professions and of the small rural landowners increased considerably14. As shown by Alain Guillemin in the case of the Normandy department of Manche, only part of the ruling milieus identified with the aristocracy and rich landowners from the bourgeoisie: in company with the former elites whose supremacy was based on wealth, a distinct lifestyle and the prestige of their name, were members of the socially rising middle classes (who had completed secondary school and university and gained access to public functions, well-off shopkeepers and business people) who, between 1830 and 1875 played an important role in the social and associative life of the department and in that way strengthened their positions in institutions of local power15. In addition – a factor we return to further on – a large section of former notables maintained their political preeminence in the Republican framework by adapting to the new forms of political competition inspired by universal suffrage.

Social Characteristics of Members of Parliament (1871-1936).

The Third Republic was nonetheless a period of considerable renewal of the elites, since it reinforced the democratization movement having begun in local power circles in the 1830s and accelerated it in milieus of parliamentary representation and the State. The early nineteenth century monarchical regimes had endorsed the political dominance of the nobility (to which between 40 % and 50 % deputies belonged during the Restoration, and approximately 25 % during the July Monarchy) and rich landowners, aristocratic or common, and the high public administration (these last two categories dominated the lower chamber with 80 % of its members in 1830 and 67 % in 1840)16. The Second Empire had not profoundly modified the face of parliament: the liberal professions were still under-represented, the petty bourgeoisie almost absent, whereas functionaries and independent landowners (respectively over a third and 20 % of parliament in 1852) maintained their preeminence17.

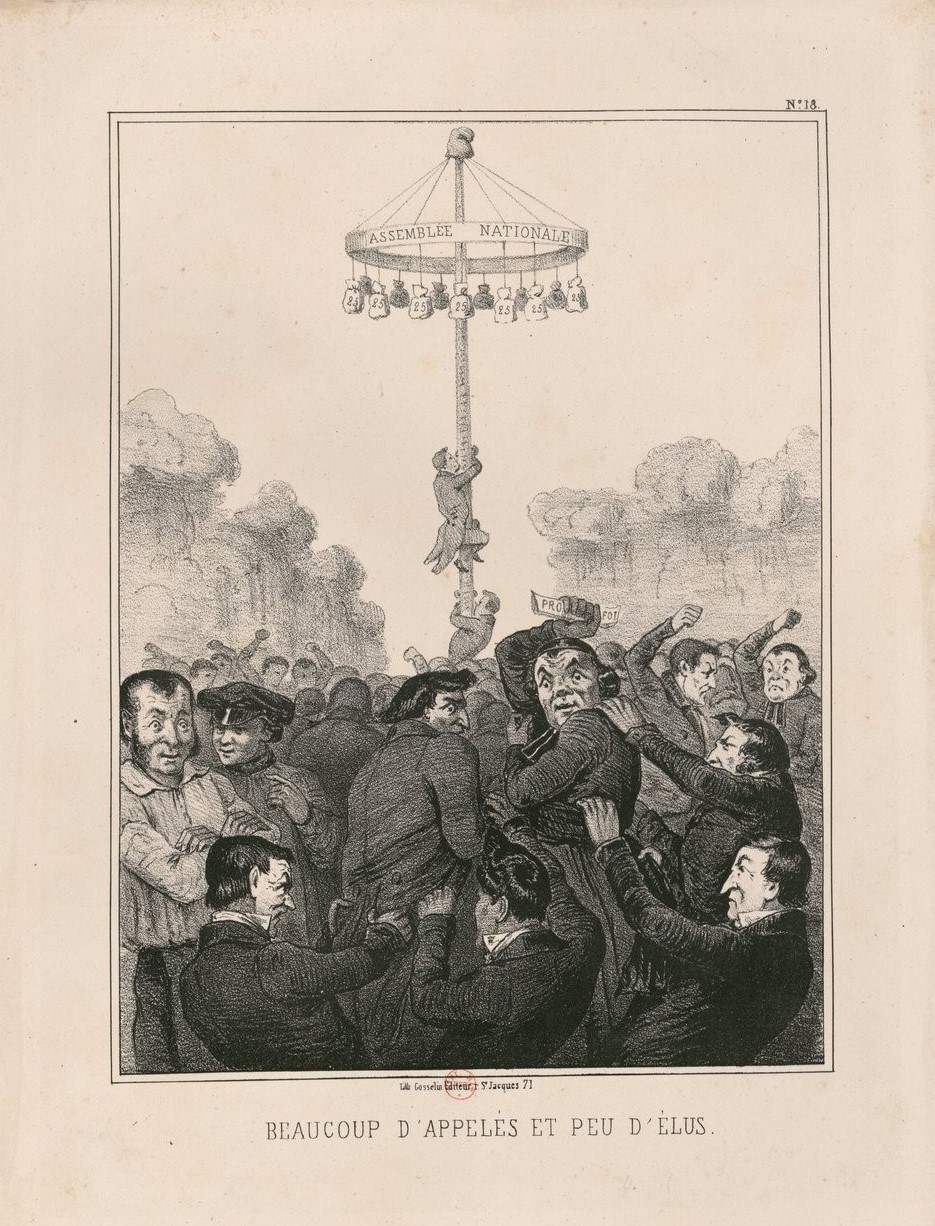

“Beaucoup d'appelés et peu d'élus”, (estampe, 1848).

The Republicans' electoral victories, beginning with the legislative elections of 1876 and 1877, show a clear reversal, and were simultaneous with the entry into the Chambre of representatives from the liberal and intellectual professions, who continually made up close to half the deputies between 1876 and 1893. To be more precise, lawyers and legal professionals accounted for 36 % of those deputies in 1876 and 30 % in 1893, doctors 7 % and 11 %, at those respective dates, and the proportion of journalists and professors approximately the same. The number of independent landowners dropped from 9 % to 5 % during that same period and that of high-level functionaries wavered between 6 % and 10 %, a much lower proportion than in previous epochs18. We can see similar tendencies in government personnel: among ministers serving between 1871 and 1914, 34 % were lawyers, 17 % professors or journalists, 12 % high-level functionaries or magistrates, and only 1 % landowners19.

The democratization of political elites is therefore a relative matter. The Republican version, the rise of “new” social classes succeeding to obsolete notables, offers only a reductive, imperfect image of the process and its context. Access to the ruling class remained reserved to members of the upper class, even if on the national scale, it extended to parts of the lower and middle bourgeoisie that were upwardly mobile socially and who, in the name of merit based on educational and professional achievements, demanded the right to participate in the governing of public affairs. On the level of local powers, it extended to a wide range of professions involved in local structuring entities (sociability spaces, cooperatives and associations, schools and administrations), and for that reason able to compete with the established elites in matters concerning social influence and political credit.

Jules Didier, Jacques Guiaud, Le Palais du Corps législatif après la dernière séance. La proclamation de la déchéance du Second Empire en septembre 1870, (1871).

Notables and political professionals

The emergence of these “new men” went along with changes in political practices, techniques for mobilizing the electorate and standards of representative legitimacy. To borrow the terms of Max Weber, the domination of notables lay in their capacity to exercise a political activity thanks to their material well-being, the free time it allowed them and the “social esteem” they enjoyed due to having belonged to an illustrious social milieu (attested by their family origins), their honorary status and the adoption of a “manner of life” in conformity with that status20.

Alexis de Tocqueville, deputy of the Normandy department of Eure between 1839 and 1851 and its General Councilor from 1842–1851, often serves to illustrate this point. Descendant of an old aristocratic line, living in Paris but residing regularly in the château he owned on his land, de Tocqueville was elected there by a very large majority, both by censitaire suffrage (he obtained, for example, 71 % of the votes in the legislative elections of 1842) or universal (87 % of the votes in the 1849 elections). These successes were due to his high rank in the hierarchy of statutory prestige, his noble inheritance and to his position as an eminent legal advisor and renowned intellectual, as well as his familiarity with the upper spheres of State power. They were also the result of his constant activity in his constituency: charity work, interventions in administrations to satisfy electors' demands (nominations, awards), participation in local economic life (presiding over the local Farmers Association, for example), management of political support networks (electoral agents, affiliated local deputies, allied press, etc.)21.

This combination of local anchorage, social power, moral authority and the capacity for mediation with the State is found in all the great notables of the July Monarchy studied by André-Jean Tudesq22and among much more modest families of the nobility in the rural department of Lozère in the South of France, who owe their reputation and power to the possession of wealth and the prestige of the name, as much as to the possession of a “client capital transmitted and inherited from generation to generation”23.

As suggested by these examples, it would be an exaggeration to attribute a population’s allegiance to notables to a passive recognition of the “de facto supremacy of natural social authorities”24. This allegiance was acquired and maintained at the price of constant attention to the care of their electors' loyalty (private assistance, clientelism), of consolidating their influence on administrative officials (able to direct state employment, subsidies and collective works towards their constituencies) and of proof of a “specific social honor” (manifesting itself in distinctive manners of life and the exercise of public activity conceived of as a moral and social duty)25.

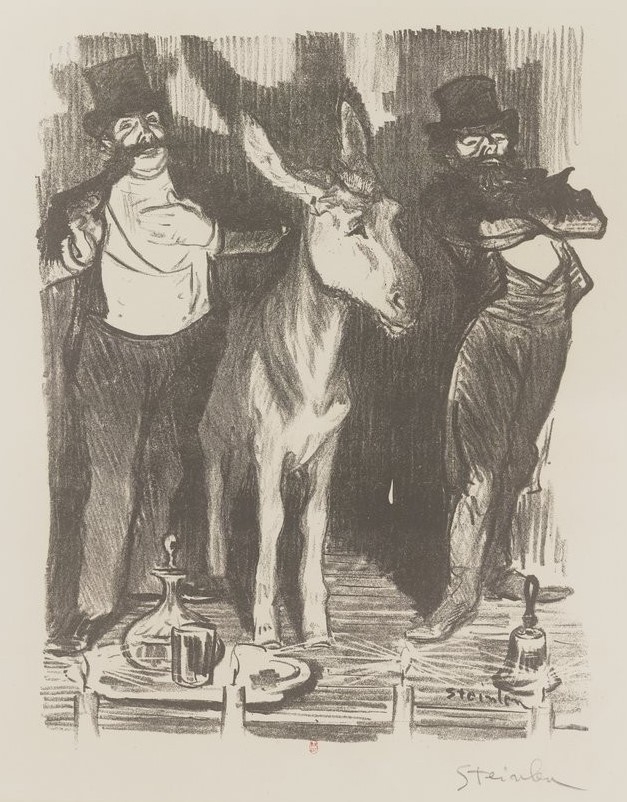

In the elections walked in all Paris on a cart by the anarchist Zo of Axa, the donkey is finally embarked by the cops.

On Sunday, May 8th, 1898, polling day legislative, the Parisians were able to cross in the street a white donkey transported on a cart pulled by a band of olibrius who call the Parisians to cast a null vote, the donkey in question. This idea of absurd application even surrealist was born in the fertile imagination of the anarchistic satiric journalist Zo of Axa.

During the nineteenth century, several phenomena contributed to undermining the socioeconomic and cultural foundations of the power of the notables. The decline of land rent in the last third of the century weakened the big landowners, many of whom, in earlier prosperous decades, had not made the investments necessary to modernize their farms. Attracted by city life, liberal professions or high level functionaries, more and more absent from their land, gave over the management to stewards or “farmers”. As a result, “the former allegiance to a ruling class both present and active, exercising a role of protection and command in all sectors of life” tended to disappear in favor of a “feeling of unanimism directed against the world of the wealthy living outside the community”26or against their local auxiliaries, who then had the difficult task of dealing with the peasants’ recriminations when the agricultural crisis affected their activities and incomes. This became all the more marked due to the increase in factories in rural areas, plus the development of small and medium-sized farms, and of industrial and commercial enterprises in cities, all of which led to the formation of new social elites able to replace notables in their functions of patronage and the political leadership of populations27.

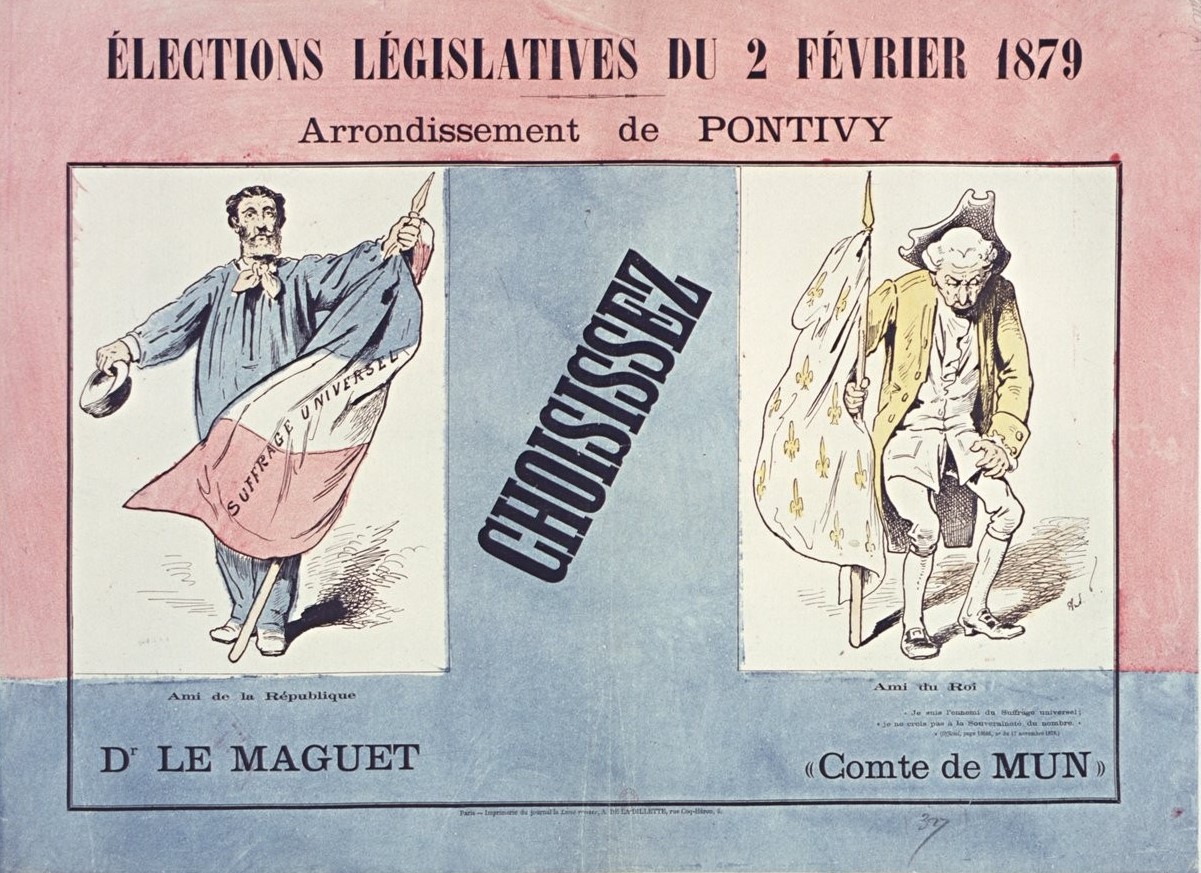

Furthermore, electoral mechanisms ensuring a majority of notables were becoming less effective, if not obsolete. With the establishment of the Third Republic and the purges in the administration that followed, royalist and conservative elites no longer benefited from the support of government officials. Thus they lost – to the advantage of Republican candidates – the crucial resource of administrative clientelism28. In addition, the broadening of suffrage and the opening of the market of elected posts to “new men” brought about transformations in electoral campaigns. Faced with more numerous and socially more diverse voters, often more educated, more politicized, in contact with intermediary elites active in rural life, it was no longer enough for notables to count on their personal loyalties and practices of patronage as guarantees for being elected. In order to impose themselves in constituencies, a majority of which had over 10,000 registered voters, it became necessary to have recourse to electoral agents and the support of an organized team to canvass electors, distribute propaganda material, organize public meetings, set up electoral committees and publish newspapers29. Many former notables or their heirs hesitated to become involved in such undertakings, either because they seemed inappropriate to their status, or because they were unable to meet the costs without the risk of undermining their patrimony, or because their influence, limited to the circles of local elites, prevented the broadening of their electoral base.

In the end, the notables’ power was weakened in its ideological foundations and in its modes of legitimation. In the words of Christophe Charle, “the ideal of a hierarchical society that did not evolve, in which it was natural for the lower ranks to recognize the leadership of the higher in exchange for services the latter rendered the peasants […] was no longer tenable in a market economy, dominated by the cities, where a completely different model of social mobility was in the air and former hierarchies were called into question30. Substituting itself for the notables model, that other “domination model” proclaimed merit, sanctioned by educational and professional achievement, as the main criterion of social distinction. During the nineteenth century it was supported by the bourgeois professional class, whose aspirations to political and social promotion it encouraged. By making room for the integration into the ruling classes of part of the middle classes and popular elites, it carved out an ideology that justified the Republic and refused the concept of a social order founded on the reproduction of wealth, prestige, and established empowerment.

Thus the notables, economically weakened and challenged in their privileges, were in competition with the new “political entrepreneurs”, who, in the race for votes, elaborated technologies of political struggle corresponding to the resources they were able to muster. Since they rarely possessed personal wealth, they formed groups and/or committees in charge of organizing the benevolent activities of their partisans, managing propaganda operations and electoral campaigns, and fund-raising among supporters. Since they rarely had the possibility of using their own assets to dispense favors on clients or practice private patronage, they were dependent – to gain anchorage locally and ensure their influence – on the support of the various entities then structuring society (educational leagues, agricultural cooperatives, hunting and leisure activity associations, fanfares, etc.). They emphasized new concepts of electoral transactions, no longer based on personal loyalties but on the support of programs and world visions, on convictions and political beliefs – which meant, on “the offer of indivisible public goods” and no longer on individual “private goods”31.

“Elections législatives du 2 février 1879 - Arrondissement de Pontivy: Choisissez... Dr Le Maguet... Comte de Mun”, (1879).

Political enterprise thus tended to become a collective undertaking. Its members were more and more dependent on the resources it supplied – the means of mobilizing the electorate, networks where they found supporters, or a common political identity in which their electors could recognize themselves. Furthermore, they soon had to devote an increasing amount of time to political activities, as the latter gradually began to require an administrative organization and agents responsible for its management, specific skills involved in winning votes and the exercise of specialized functions in electoral institutions on the national (parliament, State apparatus) or local levels (town halls, territorial administrations)32.

Recompositions of the notability

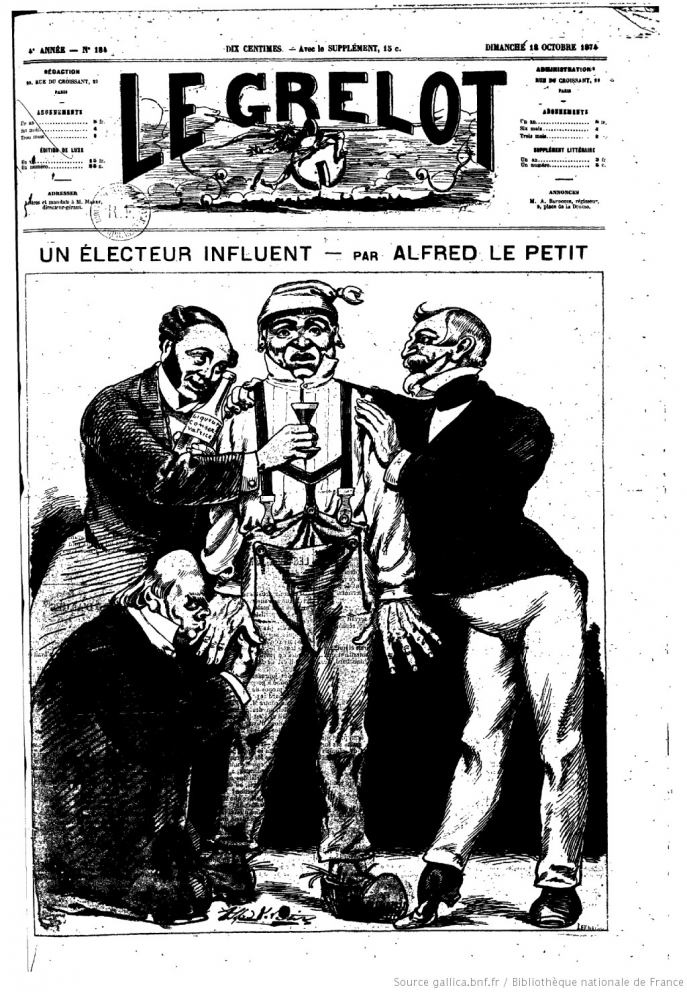

« L'électeur influent », Le Grelots, 1874.

The association of democratic politicization with a related movement involving the appearance of specific symbolic transactions (ideological and programmatic exchange replacing clientelism and patronage) and a specialized political personnel becoming autonomous might suggest a distinct separation between the figure of the notable and that of the professional political personality. Such a separation is not however clear-cut. Many members and heirs of formerly established notable families retained their political positions after the establishment of the Third Republic. In the Catholic West in particular, or in the Massif central, independent landowners and nobles preserved their hegemony by perpetuating the system of favors and means of influence (notably through the Church) that assured their local base. In those cases “the electoral institution strengthened the bonds of social domination” by making political loyalty a condition for access to the resources dispensed by the notables (employment, charity, gifts)33. “Without needing to have recourse to the harsh dismissal procedure”, André Siegfried remarked in a description of political life in Normandy at the end of the nineteenth century, “the landowner almost always influenced his tenant farmer’s vote […]. Often, whoever had the support of the château received that of the majority of the commune, either for fear of reprisals, or out of blind admiration of fortune and name”. As for farm workers, they had no “collective, thought-out political attitude, and their vote was always determined by a coin, a drink, and by the influence of the priest or especially, the master of the château”34.

However, those mechanisms did not suffice to maintain the notables’ power, now that they were faced with the activism of their Republican competitors and the peasants’ relative emancipation. Those who managed had to adapt to the new forms of organization required by electoral struggle. Baron Armand de Mackau, son of a former French peer and minister of the Second Empire, is a case in point. Elected General Councilor in 1858, then deputy of the Normandy department of Orne in 1866, aside from a period in the Chamber from 1870–1876, he retained his positions until his death in 1918 by building an organization that allowed him to “rationalize” the work of mobilizing voters: a permanent electoral team of several hundred participants – elected deputies and local personalities acting as campaign managers in each of the cantons of his constituency, electoral agents and paid collaborators. As Secretary general of the Right-wing party in Parliament as of the end of the 1880s, owner of the Journal d’Alençon, he consolidated his partisan enterprise with constant propaganda and political pedagogy (presentation of programs, publication of his speeches, commentaries on national public events, etc.) At the same time he took care of his electoral clientele (distribution of aid and subsidies to loyal mayors, charity work, various services to his administered). Thus the baron de Mackau owed his electoral successes and political longevity to a “hybridization” of political skills on one hand – the professional “know-how, both organizational and that of the terrain proper to a politician” and on the other, the “social and relational power characteristic of the notable”35.

Discours de Léon Gambetta, le 1er juin 1874

Je vous montrais tout à l’heure la démocratie nouvelle dans la commune : je pourrais vous la montrer dans le monde social, le monde de l’industrie, du commerce, de la science et de l’art ; je pourrais vous faire voir, si vous ne le saviez pas aussi bien que moi, si vous aviez d’autre peine que d’évoquer les souvenirs qui vous sont les plus familiers, - que c’est pendant les vingt ans de ce régime détesté et corrupteur, grâce au développement des moyens de transport, à la liberté des échanges, à la facilité, à la fréquence des relations ; grâce aux progrès malheureusement trop lents encore de l’instruction publique, à la diffusion des lumières, grâce enfin au temps qui est la puissance maîtresse en histoire, que s’est formée en quelque sorte une nouvelle France. […]

Ce monde de petits propriétaires, de petits industriels, de petits boutiquiers a été suscité par le mouvement économique que je viens d’indiquer ; car il ne faut pas oublier que le régime impérial a hérité ou plutôt a confisqué cette accumulation de forces, a bénéficié de ce réservoir d’éléments, de ces ressources morales et matérielles que rassemble le cours normal des événements. Tous ces éléments sont entrés successivement en œuvre, et c’est ainsi que se sont créées, formées ces nouvelles couches sociales dont j’ai salué un jour l’avènement. Messieurs, j’ai dit les nouvelles couches, non pas les classes : c’est un mauvais mot que je n’emploie jamais. Oui, une nouvelle couche sociale s’est formée. On la trouve partout ; elle se manifeste à tous les regards clairvoyants ; elle se rencontre dans tous les milieux, à tous les étages de la société. C’est elle qui, en arrivant à la fortune, à la notoriété, à la capacité, à la compétence, augmente la richesse, les ressources, l’intelligence et le nerf de la patrie. Ce sont ces couches nouvelles qui forment la démocratie ; elles ont le droit de se choisir, de se donner la forme de gouvernement la mieux appropriée à leur nature, à leurs tendances et à leurs intérêts. Dans la démocratie, c’est-à-dire dans un état politique où le travail doit tout dominer, – car dans les temps modernes le travail est le grand agent de richesse, de paix et de bonheur, – dans un état social où le plus grand nombre des travailleurs est déjà propriétaire ; où, sur dix millions d’électeurs, huit millions sont astreints au paiement des cotes foncières, il était sûr que, dès que ces sommes seraient investis du droit de se donner un gouvernement, ils choisiraient la République, parce que démocratie et République sont associées comme la cause et l’effet. (Très bien ! – Bravo ! bravo ! – Applaudissements prolongés).

Source : Discours et plaidoyers politiques de Gambetta,t. IV, Paris, Charpentier, 1881, p. 154-155.

Léon Gambetta, par Alfonse Legros (1875).

Very different itineraries led to a similar hybridization of specialized political resources and notable resources. This was the case of rich industrials who won the votes of electoral clienteles through factory paternalism and philanthropy, while at the same time managing a well structured electoral organization in their stronghold, leading a political career by constantly exercising local and parliamentary functions, making their way into national Republican machinery and thus gaining an edge over the influence of the state power apparatus36. This was also the case of the Republican notables in Corsica, who rivaled with the big Corsican families by placing themselves, as did the latter, on the terrain of clientelism, but did so by using their influence on the departmental administrative authorities and with the support of the pyramidal organization of local elected representatives who made up the skeleton of their “clan”37. Later, the radical party in the Vaucluse department in Provence also took shape around mayors and municipal councilors rallied around Édouard Daladier, to whose services they often had recourse to respond to their citizens’ requests. Their political position resulted thus as much from their affiliation with radicalism as from the personal loyalties and allegiances engendered by the policy of favors38.

In other contexts, Socialist city councilors took advantage of municipal resources (jobs, urban planning projects, social policies, associations, etc.) to constitute a personal political capital of the type notables had39. Access to elected offices in fact allowed professionalized political entrepreneurs to dispose of and distribute client-type resources to gain the loyalty of electors. However, the great majority of these resources were no longer a matter of private resources – belonging to those who dispensed them – but public resources at their disposition thanks to their electoral functions and belonging to a collective partisan enterprise. These procedures included itineraries providing access to positions of notables for professional politicians outside the world of former notables, but who “appropriate some of [their] mode of political action […] such as constant presence in the constituency, familiarity with the electors, attention to local and personal problems"40and relations of patronage giving them personal notoriety and prestige.

This dual movement, in which notables became professionalized and professional politicians became notables shows that notable practices were not a relic of the past, a sign of archaism or resistance to modern politics. They were simply adapted to changes in the technologies of electoral mobilization, making use of the new resources opened up by the expansion of local and national public action. Thus the democratic politicization and the professionalizing of political activities led, rather than to the "end of the notables", to the reconfiguration of modes of access to notability and deep changes in how it was exercised.

Modern notability

The gradual blurring of the line between the world of notables and that of professional politicians brought about a homogenization of political practices and careers taking something from both worlds41. Thus notability continued to exist, combined, in one and the same individual and itinerary, with other forms of the political profession and its exercise, even though the political and social conditions that existed when the notable class was being formed – as seen by the history of nineteenth century France – were disappearing.

Some analysts have linked the continuity of notable power to the functioning of the French politico-administrative system that was established at the end of that century and has lasted to this day. According to Pierre Grémoin in particular, the fact that state bureaucracies can only act effectively if their agents have territorial relays capable of carrying out their directives, encourages the "notabilizing" of local elected representatives. The latter monopolize mediations between the State apparatus and the spaces they represent, to the extent that they become the main regulators of "connections" between the various institutions of local power. In that way they accumulate resources allowing them to consolidate their authority and legitimacy vis-à-vis their electors: intercessions with administrations, orientation of funding and public town planning operations towards their commune or department, but also the statutory recognition consequent on the certification of their power by the power of the State. Being the result of a long itinerary of socialization inside local partisan networks and regional governments, their "bureaucratic interconnection capacity" tends to become a "personal property", a localized political patrimony attached to their person. The author concludes that therefore, "notable power is linked not to a class structure or to a given era, but to a State structure that is permanent. The resources of power change, but the exercise of power retains the same characteristics. Notables may disappear, but the notable system remains"42.

Such mechanisms are at the origin of the creation of political strongholds. Like Jacques Chaban-Delmas, mayor of Bordeaux and deputy of the Gironde department from the Liberation to the mid 1990s, deputy-mayors of large agglomerations have built up and maintained a dominant political position by cumulating national and local positions of power. Thanks to their support from the central authorities and their situation as mediator between the latter and their own region, they create tight solidarity and interdependence links with local representative entities (employers groups, associations, press, unions, possibly the Church) whose claims and demands they stand up for and who provide their support in return. By concentrating the powers of decision and mediation of local interests, and in the role of dispensers of services and favors to supporters and electors, they acquire the status of "natural" leaders in the community43.

This type of individualized and localized political hegemony can be found in other large cities (Gaston Defferre notably, deputy-mayor of Marseille from 1953 until his death in 1986, or Pierre Mauroy, chief magistrate of Lille between 1971-2001), but also on the departmental or even regional level. The Var, for example, was dominated from the 1950s to the mid 1980s by Édouard Soldani, senator and mayor of the small city of Draguignan and president of the General Council. Former member of the Resistance and active militant of the Socialist Party (thanks to which he had the support of several of his leaders, Gaston Defferre in particular), he established his leadership by placing himself at the head of a network made up of rural elected deputies and heads of secular groupings (teachers associations and unions, agricultural mutuality, freemasonry), whose loyalty he obtained by sharing both partisan identity and common values, as well as the "practical dependencies" they set up together (clientelist transactions, grants and subsidies, the personal allegiances of members of his entourage)44.

Pereire family, by Nadar (1875).

Can we then qualify the political figures described above as "notables"? If we keep to a definition of notables focused on the "plurality of social superiorities" and on the forms of authority founded on patronage that allow this plurality and that it legitimizes, the answer is clearly negative45. These political figures cannot be analyzed without examining the careers of professionalization within the parties, the identities these parties stand for and the relations they build with the groups that support them – in other words, the collective resources of a partisan organization and not simply the individualized resources of the elected deputies who represent them. Qualifying elected officials as "notable" just because they manage to stay in power over a long period of time is not only inexact, the reasons for their political longevity being very variable depending on the situation, but also carries the risk of using a common theme of political denunciation as an analytic category46.

Nonetheless, if we cease to consider notability as a situation, but in terms of the political practices involved, we have to admit the contemporary permanence of certain notable forms of exercising political power. These are above all manifest in the pervasiveness of "service activities" imposed on political figures in the form of "brokerage" of their electorate's demands with entities likely to bring about a solution (state bureaucracies and increasingly, departmental and regional assemblies, since the decentralization of local authorities which began in the second half of the 1980s)47, or in the form of clientele-type exchanges with their electors, which political analysis in France has for a long time minimized but which remains an essential aspect of the political profession48. Such forms can also be seen in the recent emphasis on the “proximity” and close relationship between elected representatives and their electorate as way of legitimizing local politics. As recent research on the the political profession has shown, the concrete and daily activities of elected politicians consist of mixed imperatives, combining professional necessities (competence in management, expertise in the political apparatus), policies (reference to ideologies and partisan identities) but "domestic" imperatives as well (physical presence on the territory, finding answers to electors' complaints, creating personal relations with electors)49.

Contrary to a current opinion, notability is thus able to adapt itself to contemporary forms of politics. The formation of a class of politicians paid for their activities, who pursue their careers in specialized institutions (local authorities, state administrations and party organizations), and have specific political competences (mastery of the technologies of electoral mobilization, organizational know-how, a capacity for ideological proposals) does not necessarily mean the disappearance of notable power. On the contrary, it has nourished that type of power, in particular because it has encouraged the assertion of new notabilities that have adapted old practices to a political profession renovated in depth.

Unless we limit the notion of notable to what André Siegfried called the "evident social authorities", which the emergence during the nineteenth century of a professionalized political personnel would have gradually supplanted, there is no reason not to use the term of notable for particular configurations of political domination that can be seen in different political contexts. In that sense, it is more important to emphasize the dynamics that go into the establishment of a personalized political patrimony and its supporting practices (particularist management of electoral clienteles, maintenance of ties with the community, protection of local interests, etc.) as well as other registers of legitimation (by the valorization of management competence, for example) – in short, it is more useful to underscore the practices that characterize notability, the itineraries and processes of becoming a "notable", than to think in terms of a notables category and what it includes.

Notes

1

Original version in Italian, “Notabili e processi di notabilizzazione nella Francia del diciannovesimo e ventesimo secolo”, Ricerche di storia politica, vol. XV, n° 3, 2012, p. 279-294.

2

André-Jean Tudesq, “Le concept de ‘notable’ et les différentes dimensions de l’étude des notables”, Cahiers de la Méditerranée, vol. 46, n° 1, 1993, p. 1-12. The author suggests reserving the notion of notable to the period from the beginning of the 19th century to the end of the 1870s, in order for it to designate a historically specific governing milieu characterized by the accumulation of positions of power in social, economic and political spheres.

3

For an overall perspective, see also: Arno Mayer, La Persistance de l’Ancien régime. L’Europe de 1848 à la Grande Guerre, Paris, Aubier, [1981], 2010.

4

Rapprochements between history and political science during the 1980s, evidenced, for example, by the creation of the review Genèses and of the “Sociohistoire” collections in the éditions Belin, nourished this type of approach and sparked a fertile renewal of thought on the political elites of the 19th and 20th centuries. The social history of politics played a central role in this renewal, thanks in particular to the important prosopographic studies on parliamentary personnel. See in particular: Jean-Marie Mayeur, Jean-Pierre Chaline, Alain Corbin (dir.), Les Parlementaires français de la Troisième République, Paris, Publications de la Sorbonne, 2003.

5

Maurice Agulhon, “Présentation”, in La Politisation des campagnes au XIXe siècle. France, Italie, Espagne, Portugal, Rome, École française de Rome, 2000, p. 3.

6

I return here to the theses of Maurice Agulhon in his study of the Var department in the first half of the 19th century: La République au village. Les populations du Var de la Révolution à la IIe République, Paris, Le Seuil, 1979, in particular p. 147-284.

7

For a synthesis, see: Nicolas Roussellier, “Les caractères de la vie politique dans la France républicaine 1889-1914”, in S. Berstein, M. Winock (dir.), L’Invention de la démocratie. 1789-1914, Paris, Le Seuil, 2002, p. 382-414; or Yves Déloye, Sociologie historique du politique, Paris, La Découverte, 2007 (which also provides a full bibliography).

8

See also: Philippe Vigier, “Élections municipales et prise de conscience politique sous la monarchie de Juillet”, in La France au XIXesiècle. Études historiques, Paris, Publications de la Sorbonne, 1973, p. 278-286; or Christine Guionnet, L’Apprentissage de la politique moderne. Les élections municipales sous la monarchie de Juillet, Paris, L’Harmattan, 1997.

9

Eugen Weber, Peasants into Frenchmen: The Modernization of Rural France 1870–1914, Stanford University Press, Stanford, California 1976, p. 242. It is in these terms that the author describes "the transition from traditional local politics to modern national politics", studied in detail in chapter 15.

10

For a discussion of research on politization, see: Gilles Pécout, “La politisation des paysans au XIXe siècle. Réflexions sur l’histoire politique des campagnes françaises”, Histoire et sociétés rurales, n° 2, 1994, p. 91-125.

11

See for example a lecture given in Auxerre, June 1, 1874, celebrating the advent of “new layers that form democracy” coming from “the world of small landowners, small industrials, small shopowners” and who constitute the material and moral backbone of the Republic” (reproduced in Discours et plaidoyers politiques de Gambetta (éd. J. Reinach), t. IV, Paris, Charpentier, 1881, p. 155).

12

Maurice Agulhon, “Les paysans dans la vie politique”, in G. Duby, A. Wallon (dir.), Histoire de la France rurale. III. Apogée et crise de la civilisation paysanne. 1789-1914, Paris, Le Seuil, 1976, p. 314. The formula “end of the notables” is borrowed from an essay by the publicist Daniel Halévy (La Fin des notables, Paris, Grasset, 1930), in which he described the failure of the former conservative elites to survive the end of the Second Empire and bar the way to the Republicans.

13

Jean-Marie Mayeur, Les Débuts de la IIIe République. 1871-1898, Paris, Le Seuil, 1973, p. 51.

14

Jocelyne George, Histoire des maires. 1789-1939, Paris, Plon, 1989.

15

Alain Guillemin, “Aristocrates, propriétaires et diplômés. La lutte pour le pouvoir local dans le département de la Manche”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 42, 1982, p. 33-60.

16

Guy Chaussignant-Nogaret (dir.), Histoire des élites en France du XVIe au XXe siècle, Paris, Tallandier, 1991, p. 288-301. The last two categories often overlap, high civil servants recruited mainly from landowning notable families.

17

Christophe Charle, Histoire sociale de la France au XIXe siècle, Paris, Le Seuil, 1991, p. 76.

18

Mattei Dogan, “Les filières de la carrière politique en France”, Revue française sociologie, vol VIII, n° 4, 1967, p. 468-492. See also: Daniel Gaxie, Nicolas Hubé, “Detours to Modernity: Long-Term Trends of Parliamentary Recruitment in Republican France 1848-1999”, in H. Best, M. Cotta (dir.), Parliamentary Representation in Europe 1848-2000. Legislative Recruitment and Careers in Eleven European Countries, Oxford & New York, Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 88-137.

19

Jean Estèbe, Les Ministres de la République. 1871-1914, Paris, Presses de la FNSP, 1982, p. 105.

20

Max Weber, Économie et société, t. 1, Paris, Plon, 1971, p. 298-299.

21

Alain Guillemin, “Aristocrates, propriétaires et diplômés. La lutte pour le pouvoir local dans le département de la Manche”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 42, 1982, p. 48-49. On the notable activities of Alexis de Tocqueville, see also Delphine Dulong, La Construction du champ politique, Rennes, PUR, 2010, p. 66-68.

22

André-Jean Tudesq, Les Grands notables en France (1840-1849). Étude historique d’une psychologie sociale, Paris, PUF, 1964.

23

Yves Pourcher, Les Maîtres de granit. Les notables de Lozère du XVIIIe siècle à nos jours, Paris, Olivier Orban, 1997, p. 382.

24

As written by André Siegfried in his Tableau politique de la France de l’Ouest published in 1913 (Paris, Imprimerie nationale, 1995, p. 89).

25

The expression is from Max Weber (Économie et société, t. I, Paris, Plon, 1971, p. 741). The conduct of notables as an expression of social duty embodied in honorable behavior (commitment to the public good, according to Greek Evergetism, and to private patronage, the show of power but also of disinterested giving and devotion) is studied in detail in another very different context, that of ancient Greece and Rome, by Paul Veyne (Le Pain et le cirque. Sociologie historique d’un pluralisme politique, Paris, Le Seuil, 1976).

26

Nicolas Roussellier, « Les caractères de la vie politique dans la France républicaine, 1889-1914 », in S. Berstein, M. Winock (dir.), L’Invention de la démocratie, 1789-1914, Paris, Le Seuil, 2002, p. 383.

27

For a ore detailed analysis of these phenomena, see for example chapters 1 and 5, devoted to France, in: Dominique Barjot (dir.), Les Sociétés rurales face à la modernisation, Paris, SEDES, 2005.

28

On the political use of the administration during the Third Republic, see: Jean-Pierre Machelon, La République contre les libertés?, Paris, Presses de la FNSP, 1976, p. 327-398; on the role of prefectoral administration in particular: Gildas Tanguy, Corps et âme de l’État. Sociohistoire de l’institution préfectorale (1880-1940), doctoral thesis in political science, Université Paris 1, 2009.

29

Raymond Huard, Le Suffrage universel en France. 1848-1946, Paris, Aubier, 1991, p. 260-261. The maximum was 30,000 registered in 1881 and 40,000 in 1928. Conditions for mobilizing an electorate were thus very different from those that prevailed during the regime censitaire. In 1846 for example, three quarters of the electoral colleges had less than 600 electors (Delphine Dulong, La Construction du champ politique, Rennes, PUR, 2010, p. 65).

30

Christophe Charle, Histoire sociale de la France au XIXe siècle, Paris, Le Seuil, 1991, p. 232.

31

Michel Offerlé, « Mobilisation électorale et invention du citoyen. L’exemple du milieu urbain français à la fin du XIXe siècle », in D. Gaxie (dir.), Explication du vote. Un bilan des études électorales en France, Paris, Presses de la FNSP, 1985, p. 166-167.

32

For a detailed analysis of these dynamics of political professionnalization (mentioned here in terms borrowed from Max Weber, Économie et société, t. I, Paris, Plon, 1971, p. 298-299), see: Éric Phélippeau, “Sociogenèse de la profession politique”, in A. Garrigou, B. Lacroix (dir.), Nobert Elias. La politique et l’histoire, Paris, La Découverte, 1997, p. 69-92.

33

Alain Garrigou provides a number of examples in his Histoire sociale du suffrage universel en France. 1848-2000, Paris, Le Seuil, 2002, in particular p. 80-108.

34

André Siegfried, Tableau politique de la France de l’Ouest [1913], Paris, Imprimerie nationale, 1995, p. 313.

35

Éric Phélippeau, “La fin des notables revisitée”, in M. Offerlé (dir.), La Profession politique XIXe-XXe siècles, Paris, Belin, 1999, p. 89. See also: L’Invention de l’homme politique moderne. Mackau, l’Orne et la République, Paris, Belin, 2002.

36

The Menier family, important chocolate manufacturers in the Paris area, or Léon Chiris, perfume dealer in the Alpes-Maritimes, are good examples for the period from the 1870s to the first World War. See respectively Nicolas Delalande, “Émile-Justin Menier. Un chocolatier en République”, Politix, n° 84, 2008, p. 9-33; and Jacques Basso, Les Élections législatives dans le département des Alpes-Maritimes de 1860 à 1939, Paris, LGDJ, 1968 (quoted by Nicolas Roussellier: “Les caractères de la vie politique dans la France républicaine 1889-1914”, in S. Berstein, M. Winock (dir.), L’Invention de la démocratie. 1789-1914, Paris, Le Seuil, 2002, p. 399).

37

Jean-Louis Briquet, “Potere dei notabili e legittimazione. Clientelismo e politica in Corsica durante la Terza Repubblica”, Quaderni storici, t. XXXII, n° 1, 1997.

38

Frédéric Monier, La Politique des plaintes. Clientélisme et demandes sociales dans le Vaucluse d’Édouard Daladier (1890-1940), Paris, La Boutique de l’Histoire, 2007, in particular chapter 4 devoted to the 1920s.

39

Cf. for example the case of Roubaix, a large working-class city in the Nord department, won by the socialists as of 1892, studied by Rémi Lefebvre: “Ce que le municipalisme fait au socialisme. Éléments de réponse à partir du cas de Roubaix”, in J. Girault (dir.), L’Implantation du socialisme en France au XXe siècle. Partis, réseaux, mobilisation, Paris, Publications de la Sorbonne, 2001, p. 13-141.

40

Alain Garrigou, “Clientélisme et vote sous la IIIe République”, in J.-L. Briquet, F. Sawicki (dir.), Le Clientélisme politique dans les sociétés contemporaines, Paris, PUF, 1998, p. 39-74.

41

Eric Phélippeau, “La fin des notables revisitée”, in M. Offerlé (dir.), La Profession politique XIXe-XXe siècles, Paris, Belin, 1999, p. 91-92.

42

Pierre Grémion, Le Pouvoir périphérique. Bureaucrates et notables dans le système politique français, Paris, Le Seuil, 1976, p. 261. See more generally chapters 9 and 10 for the study of notables power.

43

Jacques Lagroye, Société et politique. Jacques Chaban-Delmas à Bordeaux, Paris, Pedone, 1973.

44

Frédéric Sawicki, Les Réseaux du Parti socialiste. Sociologie d’un milieu partisan, Paris, Belin, 1997, chap. 3.

45

Paul Veyne, Le Pain et le cirque. Sociologie historique d’un pluralisme politique, Paris, Le Seuil, 1976, p. 117-118.

46

Philippe Garraud, Profession : homme politique. La carrière politique des maires urbains, Paris, L’Harmattan, 1989.

47

Illustrations of the concrete and “domestic” aspects of the profession of elected representative in, notably: Éric Kerrouche, “Usages et usagers de la permanence du député”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 59, n° 3, 2009, p. 429-454; Marie-Thérèse Lancelot, “Le courrier d’un parlementaire”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 12, n° 2, 1962, p. 426-432; Patrick Le Lidec, “Les députés, leurs assistants et les usages du crédit collaborateurs. Une sociologie du travail politique”, Sociologie du travail, vol. 50, n° 2, 2008, p. 147-168; Olivier Nay, “La politique des bons offices. L’élu, l’action publique et le territoire”, in J. Lagroye (dir.), La Politisation, Paris, Belin, 2003, p. 199-203.

48

For a telling example, see the case of the city of Marseilles studied by Cesare Mattina, “Mutations des ressources clientélaires et construction des notabilités politiques à Marseille (1970-1990)”, Politix, n° 67, 2004, p. 129-155.

49

From among a large bibliography, cf. Christian Le Bart, “Les nouveaux registres de légitimation des élus locaux”, in C. Bidegaray, S. Cadiou, C. Pina (dir.), L’Élu local aujourd’hui, Grenoble, Presses universitaires de Grenoble, 2009, p. 201-211, or Rémi Lefebvre, “La proximité à distance. Typologie des interactions élus-citoyens”, in C. Le Bart, R. Lefebvre (dir.), La Proximité en politique. Usages, rhétoriques, pratiques, Rennes, PUR, 2005, p. 103-127.

Bibliographie

Maurice Agulhon, “Présentation”, in La Politisation des campagnes au XIXe siècle. France, Italie, Espagne, Portugal, Rome, École française de Rome, 2000, p. 1-11.

Maurice Agulhon, La République au village. Les populations du Var de la Révolution à la IIe République, Paris, Le Seuil, 1979.

Maurice Agulhon, “Les paysans dans la vie politique”, in G. Duby, A. Wallon (dir.), Histoire de la France rurale. III. Apogée et crise de la civilisation paysanne. 1789-1914, Paris, Le Seuil, 1976, p. 329-355.

Dominique Barjot (dir.), Les Sociétés rurales face à la modernisation, Paris, SEDES, 2005.

Jacques Basso, Les Élections législatives dans le département des Alpes-Maritimes de 1860 à 1939, Paris, LGDJ, 1968.

Jean-Louis Briquet, “Potere dei notabili e legittimazione. Clientelismo e politica in Corsica durante la Terza Repubblica”, Quaderni storici, t. XXXII, n° 1, 1997, p. 121-154.

Christophe Charle, Histoire sociale de la France au XIXe siècle, Paris, Le Seuil, 1991.

Guy Chaussignant-Nogaret (dir.), Histoire des élites en France du XVIe au XXe siècle, Paris, Tallandier, 1991.

Nicolas Delalande, “Émile-Justin Menier. Un chocolatier en République”, Politix, n° 84, 2008, p. 9-33.

Yves Déloye, Sociologie historique du politique, Paris, La Découverte, 2007.

Mattei Dogan, “Les filières de la carrière politique en France”, Revue française sociologie, vol VIII, n° 4, 1967, p. 468-492.

Delphine Dulong, La Construction du champ politique, Rennes, PUR, 2010.

Jean Estèbe, Les Ministres de la République, 1871-1914, Paris, Presses de la FNSP, 1982.

Philippe Garraud, Profession: homme politique. La carrière politique des maires urbains, Paris, L’Harmattan, 1989.

Alain Garrigou, Histoire sociale du suffrage universel en France, 1848-2000, Paris, Le Seuil, 2002.

Alain Garrigou, “Clientélisme et vote sous la IIIe République”, in J.-L. Briquet, F. Sawicki (dir.), Le Clientélisme politique dans les sociétés contemporaines, Paris, PUF, 1998, p. 39-74.

Daniel Gaxie, Nicolas Hubé, “Detours to Modernity: Long-Term Trends of Parliamentary Recruitment in Republican France, 1848-1999”, in H. Best, M. Cotta (dir.), Parliamentary Representation in Europe, 1848-2000. Legislative Recruitment and Careers in Eleven European Coutries, Oxford & New York, Oxford University Press, 2000, p. 88-137.

Jocelyne George, Histoire des maires, 1789-1939, Paris, Plon, 1989.

Pierre Grémion, Le Pouvoir périphérique. Bureaucrates et notables dans le système politique français, Paris, Le Seuil, 1976.

Alain Guillemin, “Aristocrates, propriétaires et diplômés. La lutte pour le pouvoir local dans le département de la Manche”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 42, 1982, p. 33-60.

Christine Guionnet, L’Apprentissage de la politique moderne. Les élections municipales sous la monarchie de Juillet, Paris, L’Harmattan, 1997.

Daniel Halévy, La Fin des notables, Paris, Grasset, 1930.

Raymond Huard, Le Suffrage universel en France, 1848-1946, Paris, Aubier, 1991.

Éric Kerrouche, “Usages et usagers de la permanence du député”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 59, n° 3, 2009, p. 429-454.

Jacques Lagroye, Société et politique. Jacques Chaban-Delmas à Bordeaux, Paris, Pedone, 1973.

Marie-Thérèse Lancelot, “Le courrier d’un parlementaire”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 12, n° 2, 1962, p. 426-432.

Christian Le Bart, “Les nouveaux registres de légitimation des élus locaux”, in C. Bidegaray, S. Cadiou, C. Pina (dir.), L’Élu local aujourd’hui, Grenoble, Presses universitaires de Grenoble, 2009, p. 201-211.

Patrick Le Lidec, “Les députés, leurs assistants et les usages du crédit collaborateurs. Une sociologie du travail politique”, Sociologie du travail, vol. 50, n° 2, 2008, p. 147-168.

Rémi Lefebvre, “La proximité à distance. Typologie des interactions élus-citoyens”, in C. Le Bart, R. Lefebvre (dir.), La Proximité en politique. Usages, rhétoriques, pratiques, Rennes, PUR, 2005, p. 103-127.

Rémi Lefebvre, “Ce que le municipalisme fait au socialisme. Éléments de réponse à partir du cas de Roubaix”, in J. Girault (dir.), L’Implantation du socialisme en France au XXe siècle. Partis, réseaux, mobilisation, Paris, Publications de la Sorbonne, 2001, p. 13-141.

Jean-Pierre Machelon, La République contre les libertés?, Paris, Presses de la FNSP, 1976.

Cesare Mattina, “Mutations des ressources clientélaires et construction des notabilités politiques à Marseille (1970-1990)”, Politix, n° 67, 2004, p. 129-155.

Arno Mayer, La Persistance de l’Ancien régime. L’Europe de 1848 à la Grande Guerre, Paris, Aubier, [1981], 2010.

Jean-Marie Mayeur, Jean-Pierre Chaline, Alain Corbin (dir.), Les Parlementaires français de la Troisième République, Paris, Publications de la Sorbonne, 2003.

Jean-Marie Mayeur, Les Débuts de la IIIe République. 1871-1898, Paris, Le Seuil, 1973.

Frédéric Monier, La Politique des plaintes. Clientélisme et demandes sociales dans le Vaucluse d’Édouard Daladier (1890-1940), Paris, La Boutique de l’Histoire, 2007.

Olivier Nay, “La politique des bons offices. L’élu, l’action publique et le territoire”, in J. Lagroye (dir.), La Politisation, Paris, Belin, 2003, p. 199-203.

Michel Offerlé, “Mobilisation électorale et invention du citoyen. L’exemple du milieu urbain français à la fin du XIXe siècle”, in D. Gaxie (dir.), Explication du vote. Un bilan des études électorales en France, Paris, Presses de la FNSP, 1985, p. 149-174.

Gilles Pécout, “La politisation des paysans au XIXe siècle. Réflexions sur l’histoire politique des campagnes françaises”, Histoire et sociétés rurales, n° 2, 1994, p. 91-125.

Éric Phélippeau, L’Invention de l’homme politique moderne. Mackau, l’Orne et la République, Paris, Belin, 2002.

Éric Phélippeau, “La fin des notables revisitée”, in M. Offerlé (dir.), La Profession politique XIXe-XXe siècles, Paris, Belin, 1999, p. 69-92.

Éric Phélippeau, “Sociogenèse de la profession politique”, in A. Garrigou, B. Lacroix (dir.), Nobert Elias. La politique et l’histoire, Paris, La Découverte, 1997, p. 239-265.

Yves Pourcher, Les Maîtres de granit. Les notables de Lozère du XVIIIe siècle à nos jours, Paris, Olivier Orban, 1997.

Nicolas Roussellier, “Les caractères de la vie politique dans la France républicaine, 1889-1914”, in S. Berstein, M. Winock (dir.), L’Invention de la démocratie, 1789-1914, Paris, Le Seuil, 2002, p. 382-414.

Frédéric Sawicki, Les Réseaux du Parti socialiste. Sociologie d’un milieu partisan, Paris, Belin, 1997.

André Siegfried, Tableau politique de la France de l’Ouest [1913], Paris, Imprimerie nationale, 1995.

Gildas Tanguy, Corps et âme de l’État. Sociohistoire de l’institution préfectorale (1880-1940), thèse de doctorat en science politique, Université Paris 1, 2009.

André-Jean Tudesq, “Le concept de ‘notable’ et les différentes dimensions de l’étude des notables”, Cahiers de la Méditerranée, vol. 46, n° 1, 1993, p. 1-12.

André-Jean Tudesq, Les Grands notables en France (1840-1849). Étude historique d’une psychologie sociale, Paris, PUF, 1964.

Paul Veyne, Le Pain et le cirque. Sociologie historique d’un pluralisme politique, Paris, Le Seuil, 1976.

Philippe Vigier, “Élections municipales et prise de conscience politique sous la monarchie de Juillet”, in La France au XIXe siècle. Études historiques, Paris, Publications de la Sorbonne, 1973, p. 278-286.

Eugen Weber, La Fin des terroirs. La modernisation de la France rurale, 1870-1914, Paris, Fayard [1973], 1983.

Max Weber, Économie et société, t. 1, Paris, Plon, 1971.