Starting in the 1980s, the conditions for entering EU countries became more restrictive, instigating what has since become the norm in Europe. Irrespective of individual governments, public migration policies changed, with an end to labor immigration, tougher criteria for granting political asylum, the deportation of unauthorized or convicted foreign nationals, and changes to nationality laws. Furthermore, as part of the EU construction process, the management of the circulation of people shifted to a dual regime, with, on the one hand, free circulation within the EU and, on the other, the reinforcement of its external borders. This EU framework introduced a stratified, complex space that uses a regimented set of practices and norms to view those circulating. It is a multi-layered space, characterized one the one hand by national differences stemming from each country's culture and history, and on the other by homogenization, particularly under the 1985 and 1990 Schengen agreements and the Dublin regulation1 (currently in its third incarnation, with the fourth in preparation).

In this context controlling travelers and migrants frequently involves detaining them in places resembling penitentiaries to varying degrees. In France, holding zones are extraterritorial detention zones where foreigners refused entry at the border are placed for up to twenty days while waiting to be admitted or “turned back”. These holding zones are in or near international airports, ports, roads, and railway lines. While working as a legal assistant for the Association Nationale d’Assistance aux Frontières pour les Étrangers (ANAFÉ, the French National Association for Border Assistance to Foreigners), I had access to a holding zone where I conducted observations between 2004 and 20082. This ethnographic survey of a particular form of control provides a way into examining the regime introduced in Europe over recent decades, viewed in the light of the various places it draws upon.

“What exactly is a border? It's only a line, nothing else”.

How does one end up being detained at the border? What happens there? How does one leave a detention center? And what happens once on the other side? The social banishment operated at border detention centers is hard to capture. People never recount what they have gone through due to the barriers thrown up by illegality, together with the secrecy stemming from their status as migrants and issues of anonymity and identification. These experiences thus slip beneath empirical observation. My purpose is to open up this reality to enquiry, by looking at the fabric of individual experiences of circulation and detention in holding centers, by examining the places of transit, and looking at the techniques giving rise to crossings, immobilizations, and returns. The harsh, improbable paths taken in these “individual wanderings”3 shed light on changes to public space, and to ways of relating to time, as well as telling us about the (non-)places underpinning a unique form of insertion in the state’s political organization. We therefore need to imagine a path made up of multiple stages, a collage of experiences, revealing the nodal points along the journey, tracing out possible courses, exploring forks, and highlighting tensions. Let us now turn to look at the how the system works.

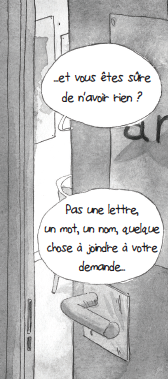

Closed waiting zone.

Extract from the graphic novel by Chowra Makaremi and Matthieu Pehau Parciboula, Prisonniers du passage, to be published at Steinkis in 2019.

Entrance into the waiting zone.

Extract from the graphic novel by Chowra Makaremi and Matthieu Pehau Parciboula, Prisonniers du passage, to be published at Steinkis in 2019.

Kadiatou Fassi was born sixteen years ago in Conakry, in Guinea. Her father had left his village to study in the capital, and never left. Her mother joined him in town after they wed, but “she didn't last”, dying shortly after giving birth to a daughter. Kadiatou's father was a shopkeeper, and business was not bad. During the 2007 strikes, when a state of emergency and curfew was declared – as Kadiatou was preparing dinner in the courtyard – Mr. Fassi received a gunshot wound during a riot in the street where his shop was, and died4.

After her father's funeral Kadiatou met one of his former clients who offered to help her leave the country. Kadiatou knew that one of her mother's cousins was in France, and dreamt of using her support to come to France too. She explained her plan, for which she had the inheritance from her father. The man answered that it was fortunate as he had to go to France too. He asked her where her cousin lived. She did not know, but had her phone number. Kadiatou had CFA 5 million. The client asked for 3 million to get a passport made for her. He would have to change her date of birth to make it look as though she were an adult. Kadiatou accepted. The client then came to collect the remaining CFA 2 million. Kadiatou Fassi took the plane with her father's client, who took care of her identity papers and plane ticket, for which a passport and visa were required, and he took her through check-in at Conakry airport.

They landed in a country she had never heard of, called Ukraine. She knew nobody and did not speak the language. She asked the client to take her to her cousin. He asked her to wait. He found her accommodation in Kiev, behind a restaurant. He sometimes came to see her. Two weeks went by. Kadiatou asked the client once again to take her to her cousin, as planned. The client started visiting less frequently. Then he came back accompanied by other men. He told Kadiatou she would have to pay for the rest of the journey. One day he gave her back her passport, together with a return ticket, and told her that she would be leaving on her own the following Tuesday. She answered that she did not know how to take a plane. The man put her in a taxi and went with her to the airport. He wrote down the name of the airline, and Kadiatou Fassi embarked without problem for the return journey from Kiev-Conakri, with a stopover in Paris5.

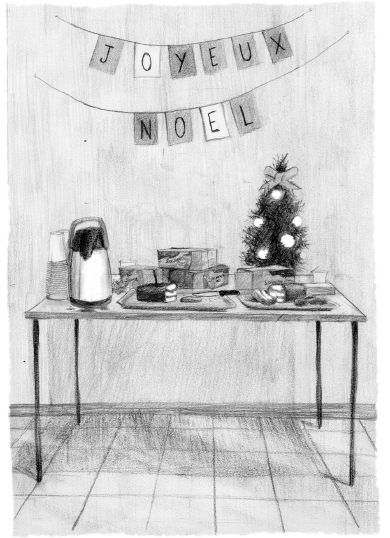

Celebrating Christmas in the waiting zone.

Extract from the graphic novel by Chowra Makaremi and Matthieu Pehau Parciboula, Prisonniers du passage, to be published at Steinkis in 2019.

Jana Fadhil, her husband Iman, and her four-year-old son had arrived in France from Damas, where they had settled after leaving Baghdad. The person who organized their journey asked them to wait before getting off the plane, the time to take their passports and customs forms to his police “acquaintances” and get them stamped. Their journey cost €13,000, paid in two installments. They had €5000 on them, the second part of the sum, and as soon as they landed in Roissy they handed it over as agreed to the person accompanying them. They also had a few hundred euros for their stay. After a few hours, seeing the man did not come back, Iman set off around the terminal looking for him. He lost his way and walked round and round. He waited until evening in front of immigration in the terminal lobby. Jana Fadhil was seven-months pregnant. She and her son lay down on the floor, and her husband slept on a chair. They bought food at the cafeteria, where a bottle of water cost €4.50 and a cake €1.50. Next day they had already spent €260 on food and phone calls, and were running out of money. The next afternoon Jana felt faint and was afraid she might lose the baby. They went to the immigration desk. They stayed there for two hours trying to catch the attention of the officers who were coming and going. Finally one of them turned to them, and Iman said in English:

- A man left us here.

- Come with us.

At the stopover in Paris, Kadiatou Fassi did not take the connecting flight to Conakry. The police intercepted her in the terminal, and took her for questioning to the station. The officers asked her about the person who had accompanied her and where he now was. In the afternoon they took her to catch the next flight, but she refused to board the plane, and told the police she did not know how she would survive back home as she had given her money to come and had lost her house. The police officers again asked her to board the plane, threatening to handcuff her otherwise. She was frightened and started crying. They took her to the police station. Kadiatou waited in a locked cell with a window giving onto the corridor. There was a concrete bench, and an out-of-order phone on the wall. Kadiatou Fassi recalled, though without really understanding what it was about, that certain people in Guinea had said that “you can ask for asylum to stop them sending you back”. A few hours later a policeman opened the door and she asked him to “help her ask for asylum”. A policeman at the front desk printed out a series of documents, asked her to sign some of them, and handed her the pile of her “police papers”. Three officers took her together with other men, women, and children to ZAPI 3 holding center (for persons whose asylum applications were pending). Upstairs they were greeted by a Red Cross employee, who handed them all sheets and a towel, and showed them to their rooms. Kadiatou Fassi had a single room in the part reserved for “unaccompanied minors”.

“The interview was though”.

Extract from the graphic novel by Chowra Makaremi and Matthieu Pehau Parciboula, Prisonniers du passage, to be published at Steinkis in 2019.

Djibril Ba was waiting in the corridor sitting on the edge of a shower cubicle. At the end of the morning someone told him in English to go down with his police papers. He went to the Red Cross office a few meters away, saying that someone had called him. A person told him he should go downstairs and buzz the intercom in the hall, where a policeman would come and open the door for him. Downstairs a policeman opened and asked for his “police papers”, then accompanied him along a corridor with a vast ceiling and through an electrified double door opened using a magnetic badge. He found himself in a waiting hall, with daylight coming through a glass door giving onto a second waiting-room at the entrance to the center. Two policemen were sitting at a small table, talking. The hall gave onto several rooms, some of which were reserved for visits from detainees' families or attorneys. Others were used for asylum request interviews with an official from the border asylum division. There were rows of chairs, and Djibril Ba went to sit on one of them. Apart from the two policemen sitting at the little desk he was on his own. A door opened at the end of the corridor. One of the policeman summoned Djibril and showed him into the office of an OFPRA official (the French Office for the Protection of Refugees and Stateless people). The man was about thirty years old and sat at a computer in an office bathed in light from a large window with handles, giving onto hedges of shrubbery. The OFPRA official started by letting Djibril speak, then asked him a few factual questions. He photocopied his veteran’s card and photos that Djibril Ba had brought with him. The interview lasted one hour, then Djibril was shown back through the security portals and corridors to the accommodation center upstairs. In the afternoon Djibril Ba heard his name called out over the loudspeaker once again. He was asked to go downstairs with his police papers. A policeman took him back to the OFPRA offices where the same official was waiting for him:

- Do you wish to add any final words?

- No, I've said everything I wanted to say. I want to have asylum for I have problems in my country.

- OK. I will photocopy all your documents and put them in your file for the Ministry of the Interior. My opinion is consultative, they are the ones who take the decision.6

Djibril Ba went back up to his room. Ten minutes later he was called down again and this time received in the office by the official, accompanied by another man. He was asked further questions. Why had he fled Mali but arrived from Côte d'Ivoire? Why had he joined the rebellion? After the interview he was asked again why he was requesting asylum. He explained once again. The two men exchanged a querying glance, then the second said: “That will be all, thank you”. The interview had lasted a few minutes.

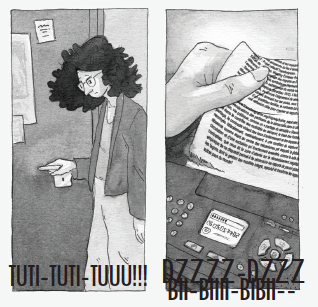

In the office.

Extract from the graphic novel by Chowra Makaremi and Matthieu Pehau Parciboula, Prisonniers du passage, to be published at Steinkis in 2019.

The day after his interview James was called downstairs with his police papers and luggage. He was afraid. He did not want to go down. He asked me several times why he had to go down with his bag. James was small and took pride in his appearance, wearing a beige beret and crocodile boots, and had a rigid gunmetal suitcase. He gave off a scent of moisturizer. He was a trade unionist from Lagos, in Nigeria. He had requested asylum and was waiting to hear the decision. He had written out his asylum account on four sheets of paper he kept on his bedside table. Very few Nigerians are granted political asylum. Between 2003 and 2007, it was one of the “main nationalities of those whose request for asylum was rejected” in France7. He calmly and meticulously packed his bag. He asked me to wait for him while he went to the toilet. A good five minutes later he completed his packing, folded up thee sheets of paper, and put them in his pocket. We went downstairs together. I wanted to check he would not be handed his refusal of asylum just as he was being taken away to be forcibly put on a plane. If that were the case then a complaint would need to be lodged with the police, for notification is meant to take place prior to boarding. Not that it would make any difference for James, for the problem was I did not know his surname. It would be hard to lodge a complaint without being able to give the surname of the person held. I did not have the time to ask James his surname, we were already in the downstairs hall. James rang the buzzer. A policeman opened, and asked him for his police papers:

- Yes, that's fine, come with me.

- Excu…

I tried to get a word in, but the door had already swung shut. Unable to say anything, I let him leave. There was nothing wrong legally with what had just happened. Louis, a Nigerian asylum seeker I had met earlier on, had followed us into the hall:

- What happened to my colleague?

- I don't know.

He asked me the same question several times. A policeman in escort uniform walked past8. I asked him if he knew “where the Nigerian had gone”. “Which Nigerian? What is his name? Do you know his MZA number9?” He was unable to help me as I did not know his name, but he did know that a Nigerian had been granted political asylum that day. It did not happen often. I asked him if it was James. Later on, through the office window, I saw James putting his grey suitcase into a Red Cross car. He was going to be taken to the Roissy airport information kiosk for those authorized to request asylum in France.

In airport terminal one, at arrivals, behind double doors no. 24, reached by a staircase accessible to technical personnel only, lies the Red Cross office where Halima Seyum was taken after being authorized to leave the holding zone to request asylum. A Red Cross employee handed her a sheet with a list of useful telephone numbers for the asylum process: France Terre d’Asile, for a registered address, the Seine Saint-Denis Prefecture, to file her request, and CIMADE, open every Tuesday from 8 AM (arrive one hour early), if she needed legal advice. The employee explained that the police had given her a “receipt slip” of her asylum request. It was imperative she went to the prefecture within eight days to register her request (examination for those in holding is a pre-screening, thus she had only received authorization to file a asylum request - the entire procedure now lay ahead of her). The first thing was to get an address, so she had to go to France Terre d’Asile who would provide her with one. Every two days she would have to go and pick up any official correspondence, which would now be sent to that address. But she still had to find somewhere to live. I received a phone call from the Roissy Red Cross social worker about Halima Seyum. Yes, I did know her. I had helped her prepare for her asylum request interview (I had “briefed” her) and left her my contact details. Halima did not know where to sleep that evening, they did not have any room for her, could I take in? I explained it was impossible (I was staying with a friend).

That’s what I thought. I’ll try to find a place at AFTAM 93, the hostels for asylum-seekers. But everywhere’s full at the moment. If the worst comes to worst, we’ll get her a hotel room for the night.

At six in the morning a group of those in holding were taken from the holding zone to the Tribunal de Grande Instance (district court). In the early afternoon, a dozen police officers showed them into the “35 quater” interview rooms (so named after the article of French law governing the placement of unauthorized immigrants in holding zones), where a liberties and custody judge would assess whether they had been detained legally, and rule on prolonging their placement in a holding zone. Jana Fadhil had been hospitalized the day after being transferred to a holding zone. Her assigned attorney presented the judge with a medical certificate drawn up by the hospital, insisting on the health problems of Jana, who was pregnant, and of Iman, who was diabetic. The judge decided not to prolong the family's placement in a holding center. After the hearing Jana, Iman, and their son were told how take the underground to Paris.

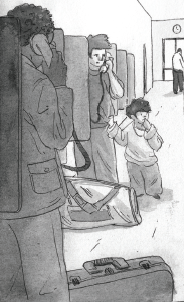

Phone booths.

Extract from the graphic novel by Chowra Makaremi and Matthieu Pehau Parciboula, Prisonniers du passage, to be published at Steinkis in 2019.

Kadiatou Fassi's cousin came to the 35 quater interview with the documents the attorney had asked her to bring: a birth certificate to prove she was a relative, and a tax notice proving she had enough income to stand guarantee for her. But Kadiatou was not called before the judge that day. Her cousin phoned the holding zone where an officer told her that Kadiatou Fassi had been “sent back” to Conakry the day before.

Djibril Ba contacted an attorney with the help of a cousin in France whose contact details he had. The attorney's fees were €900, payable in full in advance. During the audience he raised a few points of procedure, but the judge decided to prolong Djibril Ba's placement in a holding zone (along with all the other people he heard that day), “given that the interested party has formulated a request, pending, for asylum”.

Four days after his asylum interview, Abdi Hossein was called by the police. The officer who opened the door showed him to an office. An official printed out two sheets of paper, and asked him to sign at the bottom of the second one. Then he was taken back to the hall.

Considering that X… claiming to be Mr. Abdi Hossein declares he is of Somali nationality, was born and resided in Afgoy, says he is a farmer, a member of the Sheikhal minority clan and Djazira sub-clan, that the Habar Guidir clan is in the majority in Afgoy, and that, fearing for his safety, he did not often leave his home, that in December 2006 his father was shot dead in his presence in front of the door of his shop, by an armed group belonging to the Habar Guidir clan seeking to extort money; that these militiamen knew the district, came to abduct people and steal their belongings, but after this event and because of the civil war he decided to leave his country; that a friend of his father advised him to go to France to request asylum and organized his journey via Kenya;

Considering nevertheless that the account of the interested party, who claims to be of Somali nationality and be fleeing his country to protect his safety, is not convincing, that his declarations are conventional, imprecise, and lacking spontaneity, particularly with regard to the circumstances in which his father is said to have been assassinated, in his presence, in December 2006 by armed people from the Habar Guidir clan, that he is furthermore very evasive about recent politics in Afgoy where he claims to have resided, and about this geographical zone, not even knowing the names of the main districts of his town, and, further, can say little more about the conditions in which he left his country, and lastly that he can give no explanation for his departure from Kenya, merely indicating that he followed the advice of one of his father’s friends who recommended he request asylum in France, that all of these elements suggest that, contrary to what he affirms, he does not come from Somalia, his request may not be granted;

Consequently, the request to be allowed access to French territory for asylum by X… claiming to be Mr. Abdi Hossein must be regarded as clearly unfounded.

In application of article L.213-4 of the Code governing the Entry and Stay of Foreign Nationals and the Right of Asylum, it is necessary to require that he be transported back to the territory of Somalia or, if applicable, any other territory where he may be legally admissible.

Abdi Hossein went to the Red Cross offices to understand what was written on the document the police had just handed him. A Red Cross employee advised him to go to the ANAFÉ office at the end of the corridor. He was seen by Lise Blasco, an ANAFÉ volunteer, who explained to Abdi via a volunteer Somali interpreter contacted by phone that his request for asylum had been turned down. She decided to lodge an appeal with the Tribunal Administratif (administrative court) against the rejection of Abdi's request for asylum. Once again she questioned Abdi Hossein at length, with the help of the interpreter. Then she went with him to the center's infirmary where the duty doctor drew up a medical certificate certifying that Abdi had bullet impacts on each leg. Then Lise Blasco locked the office door and started drawing up the appeal, that she faxed to the clerks at the Tribunal Administratif early in the evening. A few hours later Abdi Hossein was called downstairs with his luggage.

Amadou Mporé was clearly upset on arriving in the office. He sat down in front of me and took a rolled-up tissue out of his pocket and a torn singlet with blood on it, and placed them on the table.

At 10 a.m. I was called downstairs with my luggage. I went down with my bag and buzzed over the intercom. The policeman showed me into a waiting room and asked me to wait. I sat there for two hours. When lunch was announced the policeman told me to go and eat and leave my bag there, asking me to come back and buzz again after the meal. He accompanied me to the hall where I joined the others who were going to the canteen. The people sitting at my table asked me what I was doing with the police, where I was, and why. I did not speak. I did not know them, and then there was a policeman surveilling the canteen. I went back to the waiting room around 12:30 p.m.. Shortly afterwards two policeman came in, wearing navy blue uniform, with Rangers on their feet, black gloves, and a truncheon at their belt. They told me they were going to take me to the airport. ‘Everything will be fine if you stay calm, but we will tie you up if you create a fuss.’ I cried out I did not want them to tie me up. The policeman came towards me, there were six of them in all. They were joined by colleagues wearing caps and light blue shirts who were sitting in the waiting room. They started to tie me up with straps. I cried out: ‘Leave me alone. Leave me alone’. I was crying. I took off my shirt and only had my singlet on. The policeman took hold of me by the neck and shoved me forward. I fell with my face on the ground and cut my lip. They started hitting me. They stamped with their shoes on my leg, on my shins, left knee, and right foot. One of them placed his knee on my cheek, pinning my face against the floor. The fight lasted between ten and twenty minutes perhaps. A police van came and parked in front of the exit leading from the police station to the car park, but they did not take me there. I went to sit down. Some policeman wearing escort uniform and others in light blue shirts wanted to give me a glass of water. I said ‘No, I don't want water’. I cried and cried. The young policeman who gave me some water suggested:

- Get yourself an attorney.

- If I had stolen, you could have done that to me. But I did not steal. You cannot do that to me. I am going to get an attorney. I am going to get an attorney.

The policeman told me to wait. I told them I wanted to wash. A policeman in navy blue (a strongly built mixed race guy) went with me to see the doctor. He had not been there at the same time as the others, he came later with the van. He did not touch me. In the surgery a nurse took my blood pressure, and a doctor examined me, asking me where it hurt. He gave me a painkiller. No he didn't give me a medical certificate. He kept what he wrote for himself. Then I came straight here to see you.

Evidence.

Photographs taken in the waiting zone with a phone camera after the testimony of Amadou Mporé.

Six days after arriving in the holding zone, Djibril Ba was called down with his luggage. He was handcuffed, and sent to Bamako escorted by three UNESI officers, where he was handed over to the local police.

At 11:15 PM Abdi Hossein was placed in custody. He was summoned two days later to a hearing in court 17 of the Tribunal Correctionnel (criminal court), charged with “illegal entry or stay and refusal to comply with measures denying entry to France”. He was sentenced to one month and transferred to the prison in V.

Halima Seyum called me from an Emmaüs hostel in the 14th arrondissement of Paris. She had only spent one night there, for it was an emergency hostel for the homeless. She was waiting to be placed in an AFTAM 93 hostel. I went to see her in her hostel at around 4 PM. It looked like an old school building from the early twentieth century, in the typical style of 1960s public buildings with grey lino, mismatching solid wood furniture, school chairs with grey-green metal frames, and a smell of cooking fat. We went to have a coffee in the canteen, where there were long tables with plastic tablecloths. Everything was clean and worn with use, and not yet in the plastic materials and roundish shapes found in new buildings today, and also characteristic of holding zones. Her eight-day receipt, within which time she had to request asylum at the prefecture, was due to run out the following day. The person in charge of the center said they would send her request for asylum to the prefecture before then, as the postmark would duly indicate.

A few days later the phone rang. It was someone from the “Première Classe” hotel in D. who was calling me up at Halima Seyum's request. She had not been given a place at the AFTAM hostel, but had a room in this hotel, where AFTAM had placed her until April 30, on the same floor as other asylum seekers who had not been accommodated at the hostel. The hotel lies at an exit to the outer ring road and is like an upmarket “Formule 1” hotel with orchids at reception, a clean and welcoming dining room, vending machines for coffee, cakes, and all the commodities needed by residents in a place with no staff service. There are rows of tourist coaches in the car park. Halima was worried about food. AFTAM had given her twenty euros for the week, and would give her another twenty euros the following week. It was not much. On coming back from AFTAM she had been very hungry and not felt well. So she had bought a slice of pizza in the street, but it had cost her four out of the twenty euros she had for the week. She would like to go to England. She could speak English but no French, and the person she was sharing her room with had told her there was work there. Her roommate, an asylum seeker sent from Belgium under the “Dublin II” regulation, had arrived in Europe a few years ago and knew the town.

The question of leaving for England needed consideration. Halima was admitted as an asylum seeker at the border, suggesting there was a good chance she would be granted asylum, given that border appraisals are reputed to be tougher than the in-depth OFPRA examinations of requests for asylum. We had a coffee together then went up to her room, where we sat down on her bed in the fine late afternoon sunlight:

Many people have been killed in the war between Eritrea and Somalia. War is stupid. We live here, they live there, and it is decreed there is a border, there, and because of this border, just for a line, people kill each other, there is war, and thousands of people are killed. For this line. What exactly is a border? It's only a line, nothing else. Somalia and Eritrea have fought for this line, have sent many people to war, and many people are dead. My two brothers were sent to war. Both of them. First one, and then they sent for other young men and they took the second. My brothers and sisters were scared. We did not have any news. We did not know where they were. Nobody told us anything and there was nothing in the news either. There were a lot of people killed. One day a train came, we went to the station and waited to hear the names. They read out a list, and we knew that those on the list were dead. I was scared. I waited, frightened, and when I heard the name of my brother I cried. And I stayed there listening to the list. And then they said the name of my second brother and I fainted. My neighbors took me back home. My father was already very ill at that stage … Ah, these are not happy things. Sorry, I am bothering you by telling you these things. You are bothered, but it does me good, it is a relief.

We said goodbye in early evening. We spoke a bit later on the phone. I was going to Canada for a few weeks. Halima wished me a pleasant trip and said that we would not see each other before I left, she was saying goodbye. I called in at the hotel before leaving, but she had told me that she would probably not be there because she was going with her roommate to the Salvation Army to get some food. Maybe she had not yet got back. Maybe she had already left. When I got back from Canada in May I called Pierre Gilles, at the Emmaüs hostel, who kindly put me in touch with the person at AFTAM who had looked after Halima. I phoned up to ask how she was, but the person somewhat abruptly said “she’s vanished”.

Confinement and subjectivation

How does border control operate on a daily basis? What functions does it retain in the longer term prospects of migrants arriving in France? How does the institutional management of circulation produce new ways of governing non-nationals, including “foreign nationals” and the “stateless”, people whose links to states and nations have been suspended? These are some of the questions raised by the cases sketched here. Of course, each migrant embarks on their administrative odyssey with their own particular baggage, their own knowledge, resistances, references, resources, and fears. Fereydoun Kian, with his 6 foot 6 inch frame weighing 220lbs, was placed directly in custody without any attempt to send him back under escort. Sylvie Kamanzi stuck to her administrative knowledge built up over the course of ten years of successive exiles in Rwanda and DR of Congo, first, never letting anyone know she was Rwandese, and second, having experienced police violence and extortion, always keeping silent and refusing to go for questioning. These lessons based on her experience very soon led to insurmountable misunderstandings with the administration, and she was placed on the first plane back.

People placed in Centres de Rétention Administrative (immigration detention centers) for undocumented migrants in France all have an experience, however different it may be, of living in France and of its administrative system10. But those arriving by plane have no common experience. There is no (minimal) threshold of common knowledge of the national administrative culture, of the prevailing material culture in the airports and the new asepticized centers11, or of the moral and humanitarian codes of western democracy12. There is no shared content, shared language, nor similar political background. How can such varied passages and situations – rooted in different cultural grammars, varying symbolic universes, and dissimilar forms of practical knowledge – help us grasp what it is like to be placed in a holding zone? Is the fact that they are all “held” sufficient to turn this kaleidoscope of briefly criss-crossing experiences into a shared situation?

Les Bricoleurs d’avenir

Choregraphy by Hervé Sika

Dance: Mohamed El Hajoui

With the collaboration of Chowra Makaremi

2010, Cie Mood/RV6K

To a certain extent the cultural and subjective dimension is the hidden aspect of these experiences. But equally, these experiences extend beyond the holding zone and branch out into a larger network of circulations, in which the time in holding is only one part among others. Upstream lie the global practices and spaces of mobility – which show on closer examination that any dichotomy between “enforced displacement” producing real refugees” on the one hand, and migratory strategies specific to “economic migrants” on the other, may be discarded as sociologically false. Downstream is the border apparatus connecting up illegality, criminalization, and the processing and waiting for asylum inside EU and national territories. Within this larger reality are techniques (for surveillance, classification and administration) that affect individuals, leading them to reassess their relationship with their own history, projects, and selves.

Those experiencing these techniques lastingly enter a field of government made up of administrative knowledge, adapted traceability technologies, moral judgments, and statistical endeavor. Yet these techniques and moral frameworks determining how the “non-admitted” are governed – in ambivalent, patchy, and at times illogical ways – produce specific “subjectivation”13 processes in those having to respond to it. These forms of self-apprehension undergird a shared condition, opening up a way of studying the experience of border detention. The vulnerable and the undesirable are the two aspects of the same figure. It is the combination of the two that shapes the conditions in which an individual is held, and their subjective experience of a power whose judicial and managerial nature clearly transpires in what they explain they have gone through.

Basing a policy of migratory control on detention is an ineffective and often counter-productive approach. Above and beyond the ambiguities inherent to the vision of a “fortress” Europe – yearned for by some, criticized by others – is the question of states' capability and determination to secure control in this manner, bearing in mind that people circulate along networks subject to differential management. Increased border control has never been shown to reduce the number of legal irregularities, or deliver any real reduction in illegal immigration, despite this being the argument invoked to close borders14. This raises the question of political, moral, and physical borders, and how they are reconfigured by measures to manage undesirable foreign nationals. Detention centers such as holding zones, which are invisible and screened off from view, delineate an alternative political topography. The processes of suspension, selection, and separation at work result in social and spatial exclusion, and in the long time marginalize and subalternize those prevented from exerting the right to circulate – a right to which they lay claim. Yet foreign nationals subject to the control techniques of these intermediary spaces are, though excluded, not marginal. They are, rather, true subjects of globalization, with their own political, social, and economic experiences of it. Border detention does not in fact close the territory. On the contrary, it reconfigures borders as new spaces at the heart of globalization. And in seeking to regulate access to mobility, it alters the distribution of power.

Notes

1

The Dublin regulation states that the first EU country through which asylum-seekers pass is solely responsible for examining their request.

2

The conditions in which this survey was carried out are explained in Chowra Makaremi, “Participer en observant: étudier et assister les étrangers aux frontières”, in D. Fassin, A. Bensa (dir.), Politiques de l’enquête, Paris, La Découverte, 2008, p. 165–183.

3

Marc Augé, Non-lieux. Introduction à une anthropologie de la surmodernité, Paris, Le Seuil, 1992.

4

As of January 10, 2007, in the final months of the presidency of Lansana Conté (1934-2008) who exerted authoritarian rule for twenty-three years, Guinea experienced an “unlimited general strike” conducted by trade unions and political opponents to the president's rule. This movement resulted in a “state of emergency” (AFP, Guinée: Couvre-feu assoupli, “des centaines” d'arrestations selon des ONG, 18 February, 2007) leading to a new government (AFP, Guinée: Formation d'un nouveau gouvernement pour sortir de la crise, March 28, 2007). The number of Guineans requesting asylum at the French border increased by a factor of ten, going from 0.3% of the total number of requests in 2006 to 3.2% in 2007, amounting to 177 requests in all, 163 of which were accepted (ANAFÉ 2008).

5

Field notes, February 25, 2007.

6

“Experience shows, however, that the ministry follows OFPRA opinions in all cases” (ANAFÉ 2008).

7

The Ministry of the Interior has not released data about the number of asylum requests made by Nigerians at the border that were rejected (for the period 2001-2008) but observation shows that requests presented by people from this country are fairly rarely accepted. It is certain that the Ministry of the Interior has endeavored to curb the arrival of asylum-seekers from Nigeria. The proportion of Nigerians dropped from 6.12% of all border asylum requests in 2004 to 2.4% in 2006 (ministère de l'Intérieur 2004; Anafé 2007). This is the result of management and circulation techniques applied upstream, including airport transit visas.

8

Rejected foreign nationals may be “turned back” in several ways. Either the person is conducted by air police officers to the airport border at embarkation, and then boards the plane alone, or else they are “escorted” by officers from the Unité Nationale d'Escorte, de Soutien et d'Intervention (UNESI, National Escort, Support, and Intervention Unit), a specialized brigade set up in 2001. The decision to escort deportees is taken by a separate unit of the air and border police, the Groupe d’Analyse et de Suivi des Affaires d’Immigration (GASAI, Analysis and Oversight Group for Immigration Affairs), a ministerial decision-making body with offices in ZAPI 3.

9

People placed in holding zones are registered under an MZA number issued by those running the IT systems of GTM multiservices, a private service provider that oversees holding for the Ministry of the Interior. Institutional actors in the holding zone use the registration number when designating individuals in holding.

10

Nicolas Fischer, “Clandestins au secret. Contrôle et circulation de l’information dans un centre de rétention administrative français”, Cultures et Conflits, n° 57, 2005, p. 11-38; Nicolas Fischer, “Entre urgence et contrôle. Les centres de rétention dans la France contemporaine”, Asylons, n° 2, 2007.

11

Zygmunt Bauman, Globalization: The Human Consequences, New York, Columbia University Press, 1998; Jean-François Bayart, Le Gouvernement du monde: une critique politique de la globalisation, Paris, Fayard, 2004.

12

Didier Fassin, “Compassion and Repression: The Moral Economy of Immigration Policies in France”, Cultural Anthropology, vol. 20, n° 3, 2005, p. 362-387; Didier Fassin, Patrice Bourdelais (dir.), Les Constructions de l'intolérable: études d'anthropologie et d'histoire sur les frontières de l'espace moral, Paris, La Découverte, 2005.

13

Michel Foucault, L'Usage des plaisirs. Histoire de la sexualité, Paris, Gallimard, 1976.

14

Elspeth Guild, Security and Migration in the 21st Century, Cambridge, Polity Press, 2009.

Bibliographie

Michel Agier, Gérer les indésirables: des camps de réfugiés au gouvernement humanitaire, Paris, Flammarion, 2008.

Hannah Arendt, Les Origines du totalitarisme. L'impérialisme [1951, Paris, Fayard, 1982.

Marc Augé, Non-lieux. Introduction à une anthropologie de la surmodernité, Paris, Le Seuil, 1992.

Zygmunt Bauman, Globalization: the human consequences, New York, Columbia University Press, 1998.

Jean-François Bayart, Le Gouvernement du monde: une critique politique de la globalisation, Paris, Fayard, 2004.

Marc Bernardot, Camps d'étrangers, Bellecombe-en-Bauges, Éditions du Croquant, 2008.

Judith Butler, Gayatri Spivak, Who Sings the Nation-State? Language, Politics, Belonging, New-York, Seagull Books, 2007.

Alain Brossat, La Démocratie immunitaire, Paris, La Dispute, 2003.

Marie-Claire Caloz-Tschopp, Les Étrangers aux frontières de l'Europe et le spectre des camps, Paris, La Dispute, 2004.

François Crépeau, Droit d'asile: de l'hospitalité aux contrôles migratoires, Bruxelles, Éditions Bruylant, 1995.

Didier Fassin, “Compassion and Repression: The Moral Economy of Immigration Policies in France”, Cultural Anthropology, vol. 20, n° 3, p. 362-387, 2005.

Didier Fassin, Patrice Bourdelais (dir.), Les Constructions de l'intolérable: études d'anthropologie et d'histoire sur les frontières de l'espace moral, Paris, La Découverte, 2005.

Nicolas Fischer, “Clandestins au secret. Contrôle et circulation de l’information dans un centre de rétention administrative français”, Cultures et Conflits, n° 57, 2005, p. 11-38.

Nicolas Fischer, “Les Territoires du droit”, Vacarme, n° 34, 2006.

Nicolas Fischer, “Entre urgence et contrôle. Les centres de rétention dans la France contemporaine”, Asylons, n° 2, 2007.

Michel Foucault, L'Usage des plaisirs. Histoire de la sexualité, Paris, Gallimard, 1976.

Michel Foucault, “Il faut défendre la Société”. Cours au Collège de France (1975-1976), Paris, Le Seuil, 1997.

Elspeth Guild, Didier Bigo, “La mise à l'écart des étrangers. La logique du Visa Schengen”, Cultures & Conflits, n° 49/50, 2003.

Elspeth Guild, Security and Migration in the 21st Century, Cambridge, Polity Press, 2009.

Carolina Kobelinsky, Chowra Makaremi, Enfermés dehors. Enquête sur le confinement des étrangers, Bellecombes-en-Beauge, Editions du Croquant, 2009.

Carolina Kobelinsky, Chowra Makaremi, “Confinement des étrangers: entre circulation et enfermement”, Cultures & Conflits, n° 71, 2008.

Chowra Makaremi, “Alien Confinement in Europe: Violence and the Law. The Case of Roissy-Charles de Gaulle airport in France”, in C. Hogan, M. Marín-Dòmine (eds.), Literature of concentration camps, Newcastle : Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2007, p. 39-54.

Chowra Makaremi, “Vies ‘en instance’ : le temps et l'espace du maintien en zone d'attente. Le cas de la Zapi 3 de Roissy-Charles-De-Gaulle”, Asylons n° 2, 2007.

Chowra Makaremi, “Les ‘zones de non-droit’: un dispositif pathétique de la démocratie”, Anthropologie et Société, vol. 32, n°3, 2008, p. 81-98.

Chowra Makaremi, “Pénalisation de la circulation et reconfigurations de la frontière: le maintien des étrangers en ‘zone d’attente’”, Cultures & Conflits, n° 71, 2008, p. 55-73.

Chowra Makaremi, “Participer en observant: étudier et assister les étrangers aux frontières”, in D. Fassin, A. Bensa (eds.), Politiques de l’enquête, Paris, La Découverte, 2008, p. 165-183.

Chowra Makaremi, “Violence et refoulement dans la zone d'attente de Roissy” in C. Kobelinsky, C. Makaremi (dir.), Enfermés dehors. Enquête sur le confinement des étrangers, Bellecombes-en-Beauge, Éditions du Croquant, 2009, p. 41-62.

Gérard Noiriel, État, nation et immigration: vers une histoire du pouvoir, Paris, Gallimard, 2001.

Jacques Rancière, Aux bords du politique, Paris, Gallimard, 1998.

Nikolas Rose, Peter Miller, Governing the Present. Administering Economic, Social and Personal Life, Cambridge, Polity Press, 2008.

Abdelmalek Sayad, “Immigration et ‘pensée d'État’”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 129, 1999, p. 5-14.