(Université Paris Cité - LARCA)

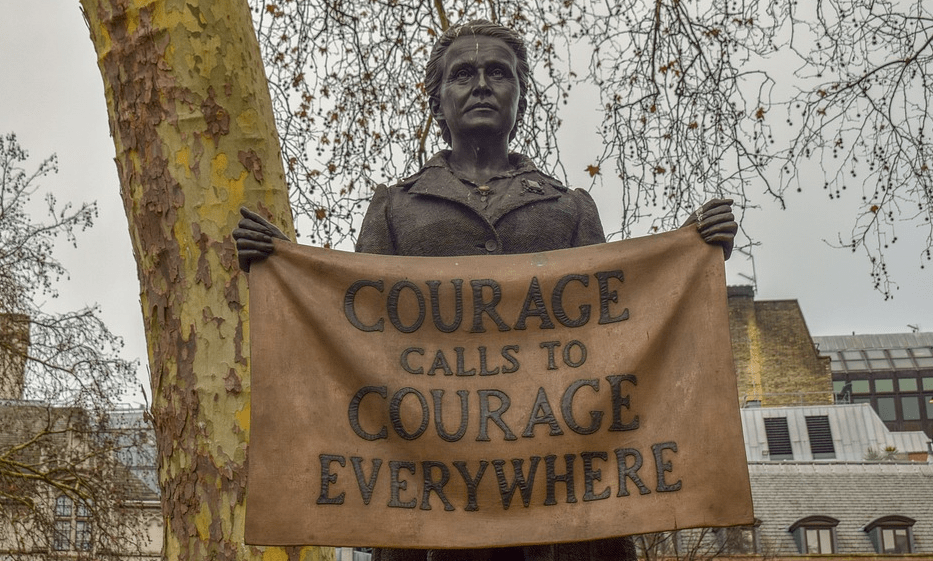

Gillian Wearing, Statue of Millicent Fawcett, Parliament Square, London.

Clarisse Berthezène interviews Julie Gottlieb and Jacqui Turner

Julie Gottlieb, Professor of Modern British History at the University of Sheffield, acted as a historical consultant to Turner-prize winning artist Gillian Wearing as she designed the statue of Millicent Fawcett that now stands tall in Parliament Square, and especially guiding her in the choice of the 59 suffrage figures who are etched into the statue’s plinth.

Jacqui Turner, Associate Professor of British Political History at the University of Reading, directed the Astor 100 project in 2019, marking 100 years of women in Parliament. Nancy Astor won a by-election in Plymouth in 1919 for the Conservative and Unionist Party, and she was the first woman to take her seat in the House of Commons. Astor 100 is a multivalent set of events which includes a new statue of Astor outside her former home in Plymouth.

2018 marked 100 years since the British Parliament passed a law which allowed some women, and all men, to vote for the first time: the 1918 Representation of the People Act. Throughout the year this important milestone in the United Kingdom’s democratic history was celebrated. A vast number of exhibitions and events were held to engage the public with the UK Parliament and the struggle for the vote. Several statues were erected between February to December 2018 to celebrate this event, and across the country. The most high-profile of these statues was that of Millicent Garrett Fawcett, leader of the National Union of Women’s Suffrage Societies. It was unveiled on 24 April, 2018 in Parliament Square, London. This is the first statue of a woman in Parliament Square, alongside eleven male figures, including Benjamin Disraeli, Abraham Lincoln, Winston Churchill, Nelson Mandela and Mahatma Gandhi. This statue is both the first of a woman and the first created by a woman in this prominent place visited by millions.

The choice of Fawcett as the figure to immortalize the suffrage movement – a decision that predated the artist Gillian Wearing’s involvement and that of the historians consulted – was itself controversial. Fawcett was a suffragist (i.e. campaigning with peaceful parliamentary methods such as lobbying, petitioning and marches). Certain voices were in favour of a suffragette (i.e. militants determined to obtain the right to vote for women by any means, by “Deed not Words” as suffragette leader Emmeline Pankhurst commanded)1. Weren’t the founders of the Women’s Social and Political Union (WSPU), Emmeline and her daughter Christabel Pankhurst, better candidates for a statue on Parliament Square? Was this an attempt to blot the suffragettes out of national memory? The battle lines in the history wars over women’s suffrage had to do with how the national narrative was being told in public spaces and who was deemed to deserve the credit as the emancipator of British women2. The heatedness of the public debate reflects the competing narratives of women’s emancipation3.

Clarisse Berthezène – Julie Gottlieb, please tell us about these competing narratives.

Julie Gottlieb – Shortly after her death, Emmeline Pankhurst’s supporters launched the campaign to erect a statue to her memory, and this has been standing since 1930, now located in Victoria Tower Gardens. While the statue was the result of a private initiative and the money was raised through private subscription, it immediately received official sanction. Indeed, it was the former Conservative Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin who unveiled Mr. A.G. Walker’s statue of Mrs. Emmeline Pankhurst on 6 March, 1930, in London and the party’s internal publication Home and Empire explained “It is appropriate that the Conservative leader should unveil the statue, for it was the Conservative Government, with Mr. Baldwin at its head, which carried out the programme of the Women’s Social and Political Union by granting “the Parliamentary vote to women on the same terms as it is, or may be, granted to men.” Interestingly enough, the British commemoration in 1968 of the fiftieth anniversary of the Representation of the People Act gave new publicity to one particular interpretation that the vote was won as a consequence of women’s militancy. In public representation and in public memory, it is striking how virtually all the attention goes to the suffragettes, some negative and critical – like George Dangerfield’s seminal The Strange Death of Liberal England (1935) – but most of it highly sympathetic and celebratory – for example Sarah Gavron’s film Suffragette (2015).

Clarisse Berthezène – What happened during the commemoration in 2018?

Julie Gottlieb – Let’s remind ourselves that this wasn’t originally government-led, but it was actually a crowdfunded campaign that emerged spontaneously from the public. And the controversy – whether it should be a suffragette or a suffragist – came about because the feminist campaigner and journalist Caroline Criado Perez had said that we need a suffragette in Parliament Square. But she approached this as a campaigner rather than as a historian, and like much of the wider public did not initially make the distinction between suffragist and suffragette. She just wanted a woman who had done something for women to join the monumental representations in the Square, and have in common their sex – all men. But then those who had specialist knowledge as well as their own passionate feelings about preserving and perpetuating the heroic memory of certain figures got very exercised about the choice of Fawcett. Understandably, it evoked strong feeling among a number of historians and other public figures who had different ideas about which women and which faction of the Votes for Women movement deserved to take center stage in this premier position in the UK’s civic and memorial culture.

In many ways the statue looks very traditional from afar. But when you get up close, you see that around the plinth, there are 59 other figures represented, and you realize it is innovative both in terms of the person who is being represented, but also the genre and the style. The fact that Fawcett is holding a banner reading “Courage Calls to Courage Everywhere” is like an invitation to democratic protest and active political engagement.

When I was approached, things were very much in train already. Gillian Wearing, the Turner Prize winning artist, had already been selected and was already working on the artistic conception of the statue. Other historians were consulted as well. It was really about establishing the criteria for who should be on the plinth. This is where fresh controversies started and quite a lot of hot potatoes were being thrown around because of course Millicent Garrett Fawcett was the leader of the National Union of Women's Suffering Societies, which is the constitutionalist non-militant organization founded in 1897.

I thought what I brought to it was that kind of distance from the heated debates and from the investment in those heated debates, which have been perpetuated generation after generation by those who supported the more constitutionalist democratic slow moving, not shaking the boat approach (NUWSS), versus the much more extravagant, dramatic and easier to ignite passions approach (W S P U). But at the same time, I was a bit puzzled by the campaign to replace Fawcett with Pankhurst. This is because Pankhurst’s statue is 40 meters away, next to Parliament. So, it wasn’t at all, as some of the staunch critics of the Fawcett statue expressed, about erasing or replacing the memory and legacy of Pankhurst with Fawcett. It was really a balancing, if you like. And balance was achieved by the end of the centenary year in any case with the unveiling in December of a new statue of Emmeline Pankhurst by artist Hazel Reeves in St. Peter’s Square Manchester, Manchester being the birthplace of the WSPU. Back to the planning of the Fawcett statue, I did issue warnings about certain figures who might well have gone around the plinth, like Mary Richardson. Richardson made a name for herself in the WSPU and took on iconic status thereafter as “Slasher Mary” as she entered the National Gallery in 1914 and vandalized Velazquez’s Rokeby Venus. She was one of the three former suffragettes to join Mosley’s British Union of Fascists in the 1930s, and she rose to the position of leader of the Women’s Section, before her disillusionment with fascism and leaving the BUF in 1935. It was clear to me that Richardson had spoiled her chances for immortality in Parliament Square as a result of her later political commitment.

Clarisse Berthezène – Jacqui, you directed the Astor 100 project in 2019. What were the origins of the project?

Jacqui Turner – My experience is quite different to Julie’s. I think to a large extent, my involvement is vested in the fact that we hold the Astor Papers here at the University of Reading and I am the Modern British Political Historian in the history department. It seemed like a natural fit when the original team lobbying for a statue of Astor were looking for a historical consultant. I was seen and understood as the keeper of the Astor Archive which lent some credibility to the campaign as we moved forward.

The idea for the Astor statue originated in Astor’s constituency of Plymouth. A bipartisan group of people, including Luke Pollard, the current Labour MP for Plymouth Sutton, and the local council, which was also predominantly Labour, decided to commemorate Nancy Astor and erect a female statue on Plymouth Hoe; there were many statues on the Hoe but none of them were female. The statue was to be crowdfunded rather than publicly financed. Many of those who contributed to the fundraising had personal connections with Astor, some would say, “oh, my grandmother voted for her”; or “my grandfather remembers her but he hated her.” It was really quite intimate. Unlike a prominent Westminster statue that Julie did, this was a local one. Most of the money raised for the statue came directly from people of Plymouth – from Plymouth Argyle Football Club to recreating tea dances on Plymouth Hoe. The other intimate part of that project was the presence of Nancy Astor’s grand-daughter on the statue committee and the general support from the Astor family. The other intimacy was that people who were very involved and who made donations had their names inscribed on the plinth surrounding the statue; as soon as your name inscribed in a public space, you become indelibly associated with it. We chose a young female sculptor, Hayley Gibbs, to do her first solo commission. It was a risk but the right decision for the right reasons. I was both historical consultant on the statue and deputy chair on the committee and part of the decision-making process for the design of the sculpture which committed me to more than the historical narrative that we were trying to create.

The date for the commemoration and unveiling of the statue, 28 November 2019, fell in the middle of one of the most divisive general elections in a generation. It became incredibly fractious and the bipartisan support that had been such a crucial part of the launching of the statue campaign began to crumble. The media began to create a maddeningly false narrative that this was a “Tory statue” especially as it was unveiled by Theresa May MP and sitting Prime Minister Boris Johnson arrived on the day. Soon after, came comments that Astor was an anti-Semite and a Nazi; suddenly people began to distance themselves from the statue. The statue was absolutely, completely and utterly weaponized by both sides of the political spectrum during a period of heightened political tension.

One of the greatest challenges of the Astor100 project was representing Astor. The difficulty of representing people from the past to a 21st century audience is that they are never going to be the personalities or pioneers that people today want them to be. However, we are the people who put them on a pedestal literally as well as intellectually. But they are from a different time and a different era. When politically that is utilized then statues become extremely problematic. And that is what happened to Astor. After #BlackLivesMatter, a list of 50 statues called “Topple the Racists” came out, Astor was the only female statue on that list. She was number 50 of the top 50 statues that needed to be removed. On June 24, 2020, the Astor statue in Plymouth was vandalized by Antifa, who present themselves as an anti-fascist group, and the word “nazi” was spray-painted on the plinth. Much of the media reported the vandalism with some enthusiasm though without any mitigation that this was a tiny group of individuals.

To some extent I took the brunt of the controversy, I became responsible for erecting the statue and I was seen as embodying Nancy Astor, I was Nancy Astor. In not so veiled language, the Independent newspaper suggested I was at best an apologist for Astor and at worst an anti-Semite. But there was an association between me and the statue, and that as the historian I should have known should better. Had this been a statue of a Labour woman I am not convinced the vitriol in some areas would have been quite so abundant.

Julie Gottlieb – This raises the issue of impact case studies that are any increasingly important element of the REF (Research Excellence Framework). There’s this pressure and this expectation that as historians and scholars, we need to be involved in knowledge exchange and impact work, and therefore there is encouragement to do that. But as Jacqui and I have discussed on numerous occasions, there’s little support, if any, in dealing with the consequences and the blow back. There is precious little support in place to protect and to come to the rescue of anyone who finds themselves trolled, bullied or abused. And of course, there are so many overlaps with the women we were representing: the statues represent women who put themselves out there, who risked their reputations and their livelihoods for a political cause. But it was, again, back to Jacqui’s point, because of the very hostile environment and the toxic environment in British politics at the time that these projects received this treatment and became weather vanes for issues only loosely related the centenaries themselves.

I would really like to stand up for the Fawcett statue in this regard, because I visited it many times, and it was striking how moving the statue is not only to women, and especially to younger women, but to men too. It is a magnet, partly because of its novelty, and because it is rousing in so many other ways. I was really encouraged by the fact that this statue has deep meaning, once you step away from the heated controversies around its conception and inception, controversies that were not always about the statue itself but rather the opportunity to rehearse other national divisions and debates. There’s clear evidence that it has deep meaning to women and it's serving the function it needs to serve. Nonetheless, I have wondered how differently all this would have played out had we being erecting a statue to Fawcett – or of anyone for that matter – after the toppling of the Colston statue in Bristol. In the last couple of years, the whole tradition of representational public monuments is being questioned and rethought.

Jacqui Turner – Who owns the past? It sounds very trite, but it is a debate about who owns the past and who owns the public space. When the two are brought together, it can create a volcano in terms of the debate. So yes, the Astor statue was roundly reported for being vandalized by a very small group but the fundraising for that statue was the product of the city of Plymouth. It was by far the majority. And I think that is the space where you can and should take the debate. How do we make historical interventions into a public space?

When I first joined the campaign, I thought my role was going to be similar to the role that Julie described. But because the original team ostensibly fell apart, suddenly there were just two of us, Alexis Bowater (Astor statue chair) and myself; there was money already crowdfunded and so we chose to continue. My role became far more involved than I’d first expected it to. The Astor family and groups of professional women in Plymouth offered their services, rallied to support us and the statue was unveiled on time.

Ultimately did the campaign and the statue matter to me? Yes, it did. Do I believe that there needs to be more representation for women? I absolutely do. And if putting a statue up supports that, then I’ll put a statue up. Do I really want to do it again? I’d rather not.

Notes

1

See June Purvis leading the objections in 2017. June Purvis, “A suffragist statue in Parliament Square would write Emmeline Pankhurst out of history”, The Guardian, 27 Sep. 2017.

2

See voices against June Purvis. Emmeline Pankhurst, “A different class of suffragette”, The Guardian, 4 Oct. 2017. Purvis after the statue was unveiled. “Misgivings over new statue and old portrait of Millicent Fawcett”, The Guardian, 25 Apr. 2018.

3

See Julie V. Gottlieb, “Suffrage Statutes and Statues: Reflections on Commemorating Milestones in the History of Women’s Emancipation in Britain”, French Journal of English Studies, vol. 62, 2019, p. 159-180.