Le meilleur moyen de faire croire que tu connais tout,

c’est de ne jamais avoir l’air étonné. [The best way to get people to believe you know everything is to never seem surprised.]

Sam Lion, played by Jean-Paul Belmondo in the Claude Lelouch film Itinéraire d’un enfant gâté (1988)

First available on bookstore shelves in the summer of 2018, Camarade Papa is the second novel by Armand Patrick Gbaka-Brédé, a writer of Ivoirian origin who is better known by his nom de plume, Gauz. The book’s publication coincided with the anniversary of its Paris publisher, Atilla, and is augmented by a brief postface entitled “Les dix ans,” a retrospective look at the trajectory of this young publishing house1. Featured in the Atilla catalogue alongside Maryam Madjidi, the Franco-Iranian author of Marx et la poupée2, Gauz is described in the postface as one of the “auteurs français bien vivants, à la plume lumineuse et caustique” [lively authors, whose pen is luminous and caustic] who have ensure Nouvel Attila’s “plus beaux succès” [greatest successes]. It is true that his first novel, Debout payé3, a description of several generations of African security guards employed by large French companies, was very well received. Capitalizing on this success, the succinct postface is rich of praise, highlighting the audacity of a publisher that rises to every challenge and prestigious comparison:

Like a certain NRF, the publishing house arose from a journal in 2007. A voracious journal that cleared libraries, as well as the city and typography. This horde dreamt of hacking the literary Pantheon by fleecing known authors in order to ensure that unknown authors were read. While the house will not create a tabula rasa, it will assuredly cultivate the literary weeds4.

It would be difficult to find a way to better express the fact that the publisher’s name should be taken literally. To cite only one of Bishop Grégoire de Tours’ (538-594) celebrated expressions, “wherever Attila has passed, the grass grows no longer” – or at a minimum, obviously, let there be no weeds… Opting for another folkloric image, one might speculate that the publisher’s purpose here is not to present itself as a kind of Robin Hood that is prepared to relieve the affluent to ensure the visibility of the “unknown.” The status attributed in this context to Gauz is clearly remarkable and merits further exploration by sociologists of literature. Claire Ducournau has called attention to the growth of publishing houses or special collections since the 1990s that have risked accusations of “ghettoizing” African literatures5. The best example is undoubtedly Gallimard’s collection “Continents noirs” [Black Continents], whose title suffices to distill these criticisms, which are all the more acerbic because the series constitutes an infelicitous chromatic counterpoint to their prestigious “Blanche” collection6.

Gauz, because he is the lone author of African origin to be published by a publishing house committed to publishing texts representing every possible perspective, takes the opposite position, however. The eulogies and prizes bestowed upon his publications illustrate the effectiveness of this strategy quite well: it is no exaggeration to affirm that, although a novice, he has been “spoiled.” As the first book to win the prize awarded by bookseller Gibert Joseph, the magazine Lire also selected Debout payé as “Best First French Novel of the Year.” For its part, Camarade Papa was awarded the “Ivoire” prize in 2018 by a jury led by the novelist Werewere Liking. It also won the Grand Prix Littéraire d’Afrique Noire. Gauz’s success is thus demonstrated by prizes that do not exclusively belong to a system of “neocolonial” recognition, to use terms used by Claire Ducournau to critique the Grand Prix Littéraire d’Afrique Noire: distinguished in Europe by a booksellers’ prize that cannot be suspected of an affinity for political institutions, it also benefits from an African recognition certified by the “Ivoire” prize.

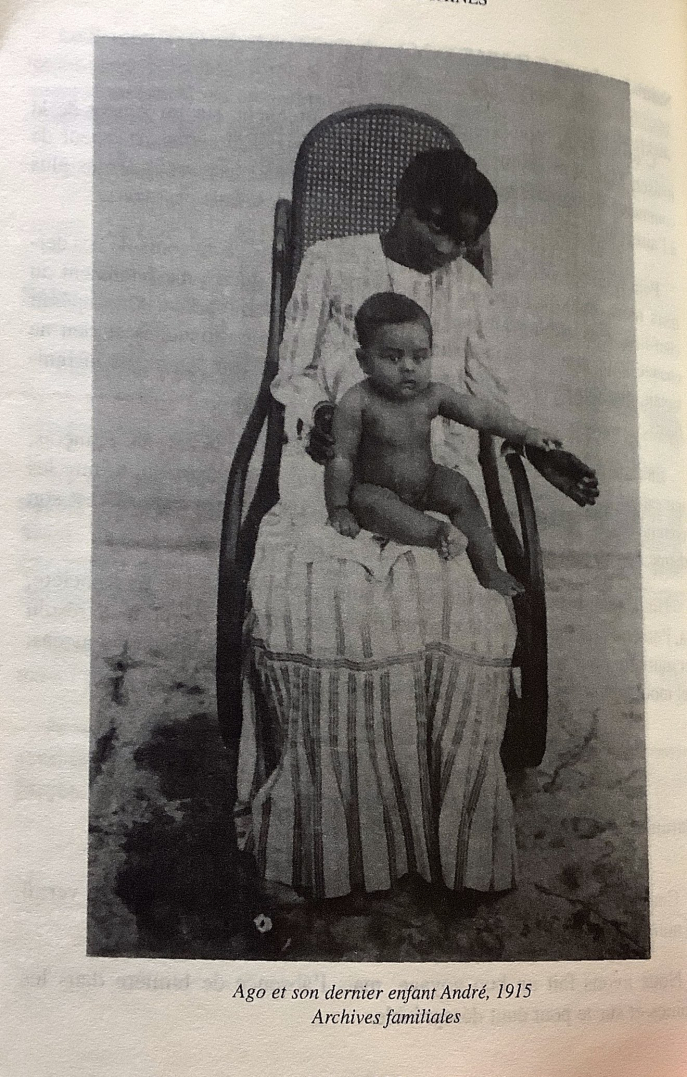

Gauz, Camarade Papa, Paris, Le Nouvel Attila, 2018.

My point here, however, is not to employ the methods of the sociology of literature to highlight the remarkable success of Gauz’ two earlier novels. Instead, I would like to propose an attentive reading of the text of Camarade Papa by inscribing it in a two-fold, diachronic profundity: first, in the history of colonization, since his novel, freely inspired by a range of archival material, eloquently illustrates the problem of “postcolonial uses of the colonial;” and second, in literary history. Concerning the second point, my analysis will focus on the continuity of the analyses of Anthony Mangeon, who argues that literary renewal on which the signers of the “Manifeste pour une littérature-monde en français” [Manifest for a world literature in French]7 in 2007 pride themselves, generally leads to the renewal of recipes that their predecessors had previously tested:

The editorial scene remains unchanged, with the race for literary prizes and the preference of Parisian publishers; and the addition to restating the past ultimately reveals itself all the more vivid in that the recovery can henceforth nourish itself from several traditions: we thus resume the tradition of the oralized narrative (“French” with Céline, but also “francophone” with Cendrars and Ramuz) to rewrite South American literature; we allude to fellow writers (Patrice Nganang, Bertène Juminer) while we clone their novels; we celebrate power literature in order to better market juju literature... Do we not run the risk of confounding writing with a certain kind of handicraft, a simple “operative gymnastics,” as Ouologuem noted in his Lettre à la France nègre?8

Here, Anthony Mangeon reveals the gap between the posture of a manifest that resembles the tones of the laudatory self-portrait that Nouvel Attila permitted themselves, and the contents of texts that merely turn gold into lead, transforming old glints of light into routine, sputtering, everyday currency.

However, few critical readings today measure this gap and read francophone literatures in a tone that is not facile complacency or journalist panegyric. Paraphrasing Mongo Beti’s diatribe when he observed that in the eyes of a journalist, “we’re always a young African author,” I could also argue that “an African novel is always new” and is systematically connected, as Bernard Mouralis notes, to a “writing of rupture that is innocent of any trace of the past.”9

Recognizing the existence of “African classics” is nevertheless the same thing as accepting more or less obvious filiations, of more or less openly borrowed citations, thereby restoring to francophone literatures their historical density. Echoing the publisher’s postface, I would therefore in turn like to add a brief retrospective note to Camarade Papa: “the ten years” covered by the novel are not only the lifespan of Nouvel Attila, pioneer of libraries and typographies, but also of a text that one could consider in many ways the hidden source of Gauz’ narrative: the Guinean writer Tierno Monénembo’s Le Roi de Kahel10.

Despite the publisher’s declarations of purpose in the postface, Gauz does not stray whatsoever from a “tabula rasa,” unless we should understand the term to denote conveniently disregarding his forerunners. In attempting to identify the sources of inspiration of Gauz’ novel, I propose to apply methods developed by Jean-Louis Cornille, who recommended interpreting literary texts by applying a detective-fiction approach. In inviting critics to behave like a “fine bloodhound,” he does not mean they should allow themselves to offer normative judgments or be prescriptive about what literature could or should be, but simply to incite the critic to undertake a genealogy of texts so as to reveal both their explicit foundations and their clandestine influences:

Writers have always proceeded thus, through successive repetitions of entire passages taken from admired or reviled books, but always retouched and arising from a profound “connivence.” And it is thus that literature advances, perpetuating itself through infinite repetition. The work “to write” is never more than an abbreviation for the word “to rewrite.”11

My goal is thus to read Gauz’ novel by inscribing it within a two-fold history of colonial conquest and literary history, which the author rewrites by turns.

“Some and others”: Maxime Dabilly and Anuman Shaoshan Illitch Davidovitch

Camarade Papa is founded on the interweaving of two narratives, each borne by a central character who will undergo an African experience. The first of these narrative threads might be described as a “colonial narrative” that recounts the French exploration and conquest of Côte d’Ivoire by the historical explorers and colonial administrators Marcel Treich-Laplène (1860-1890) and Louis-Gustave Binger (1856-1936). Initially employed as a clerk for the Elima coffee plantations, the property of a former naval officer named Arthur Verdier (1835-1898)12, Marcel Treich led important exploratory expeditions into the interior and signed a number of commercial treaties (such as the treaties of Bettié, Indiéné, Alanguoua, and Yakassé, among others). Appointed resident of France after Arthur Verdier and later colonial administrator of Côte d’Ivoire, Treich was only twenty-nine years of age when he died of a bilious fever contracted during a punitive expedition to Jacqueville.

Portrait of Marcel Treich by Charles Alluaud, 1886.

After Treich’s premature death, every trace of him was effaced by his successor, the officer Louis-Gustave Binger, who is therefore unfairly credited with founding the French colonial administration in Côte d’Ivoire. The eight chapters that Gauz devoted to this imperial gesture are attributed to the plume of a fictional character named Maxime Dabilly who leaves the city associated with his name (Abilly is the site of the confluence of the Claise and the Creuse) for Châtellerault and later, La Rochelle, where he is hired by Verdier’s trading company and volunteered to go to Africa. This decision makes Dabilly a contemporary and almost the alter ego of Marcel Treich, whom Verdier hired in 1883 to work on his plantations. Dabilly, however, shares several details with the Strasbourg native Louis-Gustave Binger. Indeed, he frequented Alsatian refugees in the arms factories of the region of Lyon, including Gauz’ efforts to transcribe the accent, supported by substituted consonants and fictional approximations of German. In this working-class milieu, Dabilly first heard the name, or rather, the nickname, of Louis-Gustave Binger and became familiar with the widespread notion that colonization provided compensation for the territorial losses that followed the debacle in Sedan:

— My yongue cousin, he is currently there [in Africa]. His name iss Louis-Gustave. At home, vee call him LG.

— Where is he precisely?

— He eez fraum Niederbronn, near Sarreguemines.

— Woher! Nicht wo!

— He asked where, not from where!

— Congue, they told me Congue.

— You should have heard Congo.

— How can I know ziss?

— In Africa, there is the Congo and the Sudan. That’s it.

— Zudan, diss tells me somesink.

— That’s what I thought. Your cousin left for Congo from Sudan […]

— Ah, his departure, he svore to come back viss a territory ten times greater dan Elsass and Lorraine togezzah.

— Nossing is greater than Alsace and Lorraine.13

Echoing both Treich Binger, Gauz’ narrator plays the role of privileged witness to the signing of the treaties that confirmed the French conquest of Côte d’Ivoire. Dabilly, who is in love with a native woman, saw himself as a representative of a form of intercultural contact that was expressed not through conquest or trade, but through love and métissage. The colonial thrust of the novel thus ends with the following passage:

“He came, the time when the fathers and mothers must sacrifice their destiny so that new times are born in which their children will live. […] I am far more than a “brôfouê,” a white, much more than an agent of the Compagnie française de Kong. I am an agent-symbol in the service of two copulating civilizations.”14

Because it is set a century later, however, the second narrative takes place within a resolutely post-colonial context15 whose every formulation is charged – for example, in the childish questioning of the novel’s title character “Camarade Papa” – with the rhetoric of communism. This time, the narrator is the young Anuman Shaoshan Illitch Davidovitch, born in the Netherlands of black or mixed parents (the eponymous Camarade Papa and Les-Grands-Soirs-Maman), who is firmly convinced that Revolution is imminent. Preparing for the Revolution, they hurriedly sent their son to stay with family in Côte d’Ivoire, but only after making her responsible for the triumph of the proletariat.

The plot’s two elements converge when it becomes apparent that Anuman is none other than Dabilly’s descendant, the fruit of a sexual relationship between “the agent-symbol”16 and a woman he met in Grand Bassam a few days after his arrival. The daughter that she bears and whom he baptizes in homage to Treich and a local queen, Alloua-Treissy, reveals herself to be Anuman’s grandmother and, like in a Molière comedy, the novel concludes with an emotionally charged scene of familial recognition. After gathering on Dabilly’s tomb (he died in 1936), the grandmother and his grandson examine the papers left by the ancestor on his death, including “a bunch of stories”17 that become the basis for the colonial aspect of Gauz’ novel. Unsatisfied with the two narrators who shared their genealogy, the conclusion thus supplies its own material pretext by inventing, in the form of Maxime Dabilly’s memoirs, an original manuscript that was adapted and transcribed by the author.

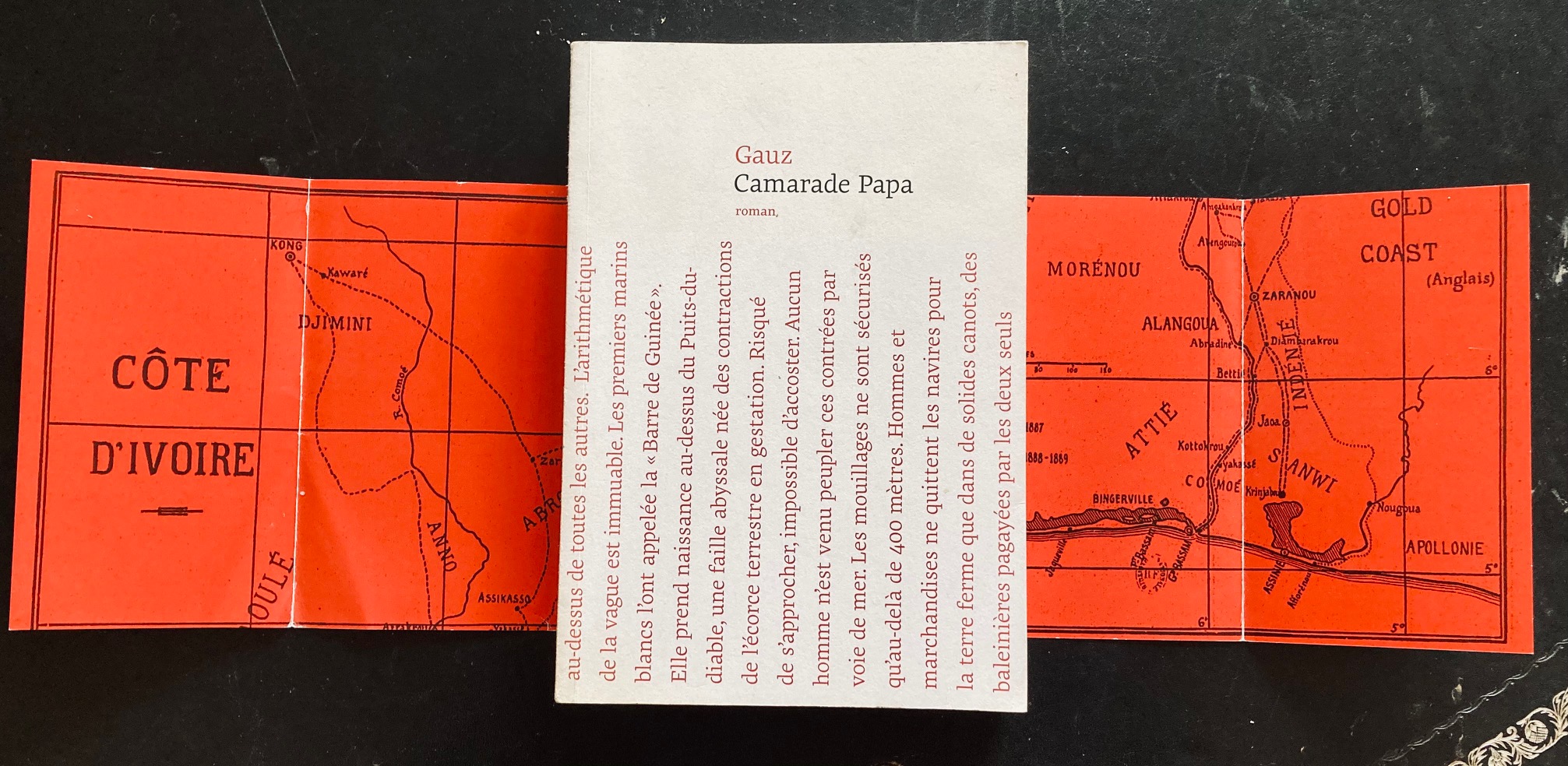

The removable banner that envelopes the book’s cover reinforces the connection between its twin narratives – one colonial, the other postcolonial. Indeed, the front cover features an image by the photographer Bernard Descamps representing a Malagasy child dressed in an oversized raincoat, arms outstretched toward the sea as if attempting to fly. The back cover shows a map of Côte d’Ivoire with dotted lines that traces Treich’s explorations from 1887 and 1889. The image suggests a link between “the postcolonial child” – the perfect representation of what Jean-Loup Amselle called “l’art de la friche” [the art of the wasteland] in 200518 – and colonial conquest, which thus represented the reverse side or implicit background of the photograph.

Map printed on the reverse side of the Camarade Papa banner.

“To both of us”: Portraits of Gauz and Alain Mabanckou as Literary Twins

Gauz’ “detective” interpretation implies first of all pausing to consider the filiations and literary influences that he displays and next, inquiring about those that he might tend to conceal. I would therefore like to launch my analysis of his novel by seeking to ascertain the source – and perhaps even more, of the twin narratives that the author of Camarade Papa combines.

First is the postcolonial aspect that centers on Hollande’s trip to Côte d’Ivoire, as narrated by Anuman Shaoshan Illitch Davidovitch. The weight that the title of Camarade Papa appears to confer to this facet of the narrative is unsupported in the body of the book. Only five chapters (“red chapter,” “flying pendulum chapter,” “high-headed chapter,” “bees and desk chapter,” “orphan chapter”), some of which are rather brief, are devoted to this facet of the novel’s plot. The literary genealogy of this childhood fiction is the basis of a relatively explicit claim. In several interviews during the opening of the Fall 2018 literary season, Gauz took pleasure in presenting himself as an accomplice, or even a double, of the writer Alain Mabanckou – who is himself adept at dualities and twins, as exemplified by Anthony Mangeon19. Gauz thus recounts that he supposedly substituted himself for his Congolese colleague during dedication sessions on several occasions. Under the camouflage of a joke, this anecdote confirmed francophone African writers’ interchangeability, despite different origins, in the eyes of Western readers. A joint interview in the magazine L’Express emphasized this shared “posture20”:

Not easy to cross paths with two grand travelers. Especially when one of them lives half the year in Los Angeles and is named Alain Mabanckou, and he racks up more miles in a year that you have in your entire life. As for Gauz, who is more often in Grand-Bassam (Côte d’Ivoire) than in Belleville, he seems to be equally impulsive. But here they are in early July in Paris. White wine and black t-shirt under a jacket for one, a beer and black t-shirt with a red polo for the other; sparkling laughter for both21.

The two writers shared cosmopolitan identities as world travelers, making them, as Alain Mabanckou has pointed out several times in literary and critical writings, veritable “migratory birds” engaged in a triangular circulation between Africa, America, and the Old Continent22. Their kinship is also vestimentary, since the two accomplices, whose embrace illuminated the interview, both presented themselves in jeans and black T-shirts, far removed from the fireman’s outfit sported by Alain Mabanckou during his 2016 talk at the Collège de France. Their vestimentary coordination reinforced the impression they are interchangeable authors, united, if one believes the article’s author, with “explosive laughter” that recalls a bit excessively, the “Banania laughter” heard “railing from every wall in France”23 by Senghor.

The similarities between the two men are not limited to shared clothing tastes or the complicity that they appear to cultivate, however. They can also be seen in their writing and in the same childhood narrative borrowed from the francophone writer of Polish origin, Émile Ajar/Romain Gary, specifically in the remarkable present of La Vie devant soi24. Indeed, in 2010, Alain Mabanckou published a loosely autobiographical childhood narrative, Demain j’aurai vingt ans, in which he returned to the Congo of the 1970s-1980s and that was narrated by his young hero, Michel. By employing a juvenile voice in Camarade Papa, Gauz acknowledge his debt towards Romain Gary more openly than Mabanckou, even assigning a social life to his young hero that resembles that of Momo, was raised by a prostitute, in La Vie devant soi. In the absence of his mother, Gauz’ lead character, Anuman Shaoshan Illitch Davidovitch, finds refuge with a “seller of kisses” named Yolanda.

In addition to these rememberings, the choice by both Gauz and Alain Mabanckou of an infantile narrative voice has a two-fold narrative advantage. First, because the puerile gaze permits them to evoke the torments of an adult world that a young narrator has not fully grasped. The childhood narrative thus illustrates the adage that truth comes out of “the mouths of children” whose naïve words naturally reveal the absurdities of modern life and the incoherence of dominant discourses. In addition to the narrative advantage of a childish narrative persona, one also often encounters a certain stylistic specificity in francophone literatures. The child-like tone of such texts does not spurn certain lexical approximations, grammatical variants, or extensive repetitions. Both Gauz and Mabanckou, for example, toy with the contrasting comic effects created by the collusion between childish vocabulary and the heavy Communist Party discourse. The narrative of a Pointe Noire childhood offered by Mabanckou in Demain j’aurai vingt ans, published by Gallimard in 2010, for example, includes several passages devoted to the political education of Congolese youth.

Alain Mabanckou, cover of paperback edition of Demain j’aurai vingt ans.

The narrator Michel, clearly the author’s alter ego, mentions forced recitations of President Marien Ngouabi’s speeches (he held power from January 1969 to March 1977) being unanimously chanted by young “pioneers” who declare themselves ready “to die for the people” and the Revolution. The schoolmaster’s words are embellished by a revolutionary lexicon that the young narrator studiously echoes:

The Master told us that the government ended up catching and imprisoning the local valets of imperialism who killed Comrade Marien Ngouabi. The Immortal One defended himself but he could do nothing because it is a conspiracy that was invented from over there in Europe, and the Europeans are too clever when they sell their plots to Africans. These local valets of imperialism who killed our Immortal One are blacks like us, Congolese like we are. The government promised that we are going to judge them and kill them by hanging in the Stadium of the Revolution in front of the People. People need to know you don’t touch immortals. So, for the moment, all that’s left is to put imperialism on trial25.

Alain Mabanckou’s recent novel, Les Cigognes sont immortelles which, like Camarade Papa, was published in the autumn of 2018, can be read as a gloss on this passage that the author attempted to expand throughout an entire volume26. Reconnecting with the character of Michel, Mabanckou returns to the assassination of Marien Ngouabi, whose causes and consequences he intends to describe through a child’s gaze once again. Even the title, which recycles the “migratory bird” metaphor so dear to Mabanckou, is a quote from a Russian communist song27 memorized in translation by Congolese schoolchildren. Gauz employs a somewhat similar tactic in which the child’s initiator is not the schoolmaster or fear of the whip, but the celebrated “Comrade Papa,” whose teaching flows from the Dutch tulip crisis to the assassination of Lumumba:

In the flow of discourse of Comrade Papa, after the Philips, there are tulips. They are Turkish flowers that caught whooping cough from the bourgeois Dutchmen a long time ago. Long before English steam, the bourgeois Dutch protesters use the Turkish flower to make a purse. The flower isn’t very beautiful, but sheep don’t graze on it. But because of their rain profits, they buy and sell weeds. They invent the capitalism of purses. It doesn’t come from England—everyone was wrong, including Marx and his angel. Starting in Holland, country after country, the USSR was infected. China was saved because Comrade Mao and his legs were able to take large steps and leaps to flee the epidemics. Comrade Papa called Holland Patient Zero. Like a researcher, he came her with Mom to understand Patient Zero and find a global vaccine against the great purse disease. I was born in Amsterdam because of tulips. At the end of this speech, there are also public pendula and suppositories of big capital and tons of abolitions28.

Both passages illustrate defectively assimilated Marxist rhetoric that distinguishes Engels’ “angels” from the valets of imperialism and other “suppositories” of big capital. The flaws in a child’s language serve as a pretext for the systematic deformation of the economic history that Comrade Papa describes, converting the first crisis of the purses into a contagious “great illness of purses” and transforming capitalism into a venereal disease. The comic inaccuracies of this child-like transposition recall the distortions of “petit nègre,” the simplified language used by colonials to communicate with riflemen recruited in Africa whose name itself echoes a child’s linguistic game. As Cécile Van den Avenne has observed, in the late nineteenth century when the term petit nègre first appeared, it was used to refer to “speaking, in this case French, like a nègre or petit nègre, i.e., like a black and a child.29”

The puerile voice itself preferred by both Gauz and Mabanckou thus constitutes a “postcolonial use of the colonial” that revives the memory of a linguistic practice characteristic of the dynamics of imperialism. In francophone African literature, the tendency toward “bad writing” justified by a childish perspective and tone is not limited to paradigmatic childhood narratives, however. In a broader sense, it is a recurrent stylistic trait among authors who seek to demonstrate divergences from French linguistic norms. This tactic was used in such foundational works as Ahmadou Kourouma’s Le Soleil des Indépendances30 and La Vie et demie by Sony Labou Tansi31. It is indeed striking to note that Gauz’ narrator duplicates Sony Labou Tansi’s characteristic syntactic structure by affirming, as his train is leaving the Amsterdam train station, “I’m going to spend a lot of time with Comrade Papa, I’m happy-and-a-half.32” The literary kinship between Gauz and Mabanckou is expressed through their shared predilection for childhood narratives that, while inducing a potentially comic narrative time-lag, favors an awkward style and assumed clumsiness that are also the trademark of a number of other francophone African authors. As will be seen later, with Gauz, this linguistic slackness is paradoxically associated with a lexicological problem that leads him to provide a glossary of consumer society in Debout-payé33 and to linger on the lexicon of colonials and colonization in Camarade Papa.

The complicity between Mabanckou and Gauz’ that was evident during the 2018 fall literary season was clear as early as 2016, when Mabanckou invited Gauz to participate in the “Écrire et penser l’Afrique aujourd’hui” conference at the Collège de France and to contribute to the published proceedings that followed. Having authored only a single novel at the time, Gauz found himself hoisted to the ranks of such authors as Mabanckou, Abdourahman Waberi, and the Haitian Academician, Dany Laferrière, who had signed “Manifeste pour une littérature-monde.” His presence at this mediatized event also contributed to a certain current of Africanist discourse that currently tends to exhibit an increasingly “literary” coloration, in the broadest sense. In fact, while the multidisciplinary Africanism of colonial times reflected a certain primacy of history and anthropology, the conference that Mabanckou put together as Chair of Artistic Creation at the Collège de France – like the Ateliers de la pensée34 in Dakar the same year at the initiative of Achille Mbembe and Felwine Sarr – discarded these previously foundational specialties in favor of allowing philosophers, critiques literary critics, and writers to sit in the front row35.

Gauz took advantage of the forum of the Collège de France to improvise as an undisciplined amateur historian. Using a familiar vocabulary and systematically deploying anecdotes in lieu of eloquent formulations, he instead showed an ability to compose a “postcolonial history of the colonial” and hence to fill the voids in the narrative of imperial conquest, or rather to fill in its blanks. I use this term—generally reserved for cartography and colonial exploration—deliberately36. Indeed, the intention of the compensatory historiography that Gauz proposed is to focus, not on a denied or negated African history, but on a colonial figure whose African celebrity—i.e., “black”—is equaled only by its metropolitan—i.e., “white”—dissimulation. Gauz’ talk began with an observation about a memorial deficit whose victim was none other than the colonial administrator Louis-Gustave Binger – and grandfather of Roland Barthes -- who held the Chair in Semiology at the Collège de France from 1977 to 1980:

I was strolling through Montparnasse cemetery looking for this tomb when I see a kind of stele on which exactly the following was written: “Louis-Gustave Binger explorer of the Niger Loop gave Côte d’Ivoire to France. Grateful France.” The guy died in 1936 and gave my great-grandfather to France. […] I know this guy Louis-Gustave. We studied at school. I know nothing about Babemba or Makoko, but I know Binger. The friend I was with didn’t know Binger. “Are you kidding? You don’t know who Binger is? He gave Côte d’Ivoire to France, my friend. It’s written in stone on his tomb, plus “la France reconnaissante.” Quick, quick—be grateful.” He didn’t know Binger. Nobody know Binger. It became the joke all weekend to ask all of my French friends who I saw, “Do you know Binger? You know Binger?” Nobody knew. But France was grateful to him for having given it such a fundamental colony. A key colony today. When I say key colony, I’m not talking about the country. Even today, it’s a key colony of France in West Africa. Nobody knew this man. We have a problem. I decided to explain who Binger was to my friends37.

Tomb of Gustave Binger in Montparnasse Cemetery.

Playing on hidden or ignored genealogies, Gauz’ talk was predicated on a postcolonial afterglow of the colonial that was revealed in the repeated assertion of the status of a “colony” (and not the “country”) that allegedly belonged to Côte d’Ivoire. According to Gauz, the persistence of imperial logics is closely associated with an astonishing contemporary case of amnesia that is obvious in the gap between the letter of the monument and the absence of reconnaissance [knowledge] or even of connaissance [knowledge] of Binger among his metropolitan friends. To believe Gauz, there is no memory, nor postcolonial use, of the colonial in France.

“The Adventure is the adventure”: Binger, Treich, and Nebout

Gauz’ talk at the Collège de France was unquestionably a matrix of the writing of Camarade Papa, in which the character Binger serves as an anti-hero as foul-smelling as he is arrogant, and quick to usurp Treich’s more legitimate glory:

Your man arrived here hungry, sick, skeletal, stinking of hyena. Even though there’s not a single white man for a thousand kilometers, he dared to pull out some kind of white man’s document to demand that we submit to him and to France! In the name of Islam, we submit only to Allah. He escaped publicly execution because Karamoko Oulé Wattara convinced the council that he was mentally ill. He was told to move on to the south where he wanted to go. He went straight north. Today, it’s been ten months and we just heard that he’s in Bondoukou, directly east. If you are saying that that man is your superior and that he’s even a captain in your army, the meeting just ended38.

Treich, on the contrary, is not only capable of finding his way, but also a connoisseur of local practices. A few pages later, the signature of the treaty with Karamoko Oulé Wattara (1889) is also presented as a “comedy in three acts by Marcel Treich,” whose successive phases took religion, the profit motive, and the local populations’ animist beliefs into account. The striking contrast between the portraits of the two men could be reduced to an onomastic comparison by a type of extreme stylization. While the comedic aspect of Gauz’ Collège de France talk was partly the product of an unflattering, elliptical play on pronunciation “les rêves de Kong de Binger” [Binger’s Kong-like dreams] (vs. “les rêves de con de Binger” [Binger’s asshole-like dreams]), Treich was granted a degree of prestige merely through the pronunciation of his name:

He [Bricard: an official whom Dabilly met in Elima] informs me that I will be assigned to a “post in a wooded zone in the north of Assinia.” In this unknown territory, I will have to build and occupy an outpost. […] What about the exact spot where I am going to settle? “Treich is the only one who has gone that far up. He will guide you.” What about the dates of my assignment?” “Treich will decide. He always wants to leave time for acclimatation.” All of the answers go through Treich, the French resident delegate. A saint. Treich knows. Treich understands. Treich can. Treich goes. People don’t speak of him—they invoke him. His name pronounced with a whisper at the end adds to his mystique: Treicccchhhh!39

This prolonged sound at the end of Treich’s name contrasts with the insulting appendix that precedes Binger’s name. Treich is represented as a an influential, near-prophetic figure. The novel’s colonial dimension cannot be reduced to these occasional contrasts between the two adventurers from a postcolonial retrospective point of view, however. In an interview with Natalie Levisalles in En attendant Nadeau, Gauz sketches a further intertext by making the main character, Maxime Dabilly, the epigone of a third member of the colonial apparatus who is less well known Treich and Binger. Indeed, he confirmed having found inspiration in a collection of letters by Albert Nebout that was published in 1995, nearly a hundred years after they were written and over fifty years after their author’s death:

And then I assembled some material. In Abidjan in the “bookstores on the floor,” you can find incredible books that have spent years in cellars or suitcases and that exist nowhere else. One book that helped me a great deal was the correspondence of Albert Nebout, who lived in Côte d’Ivoire from 1894 to 1910. He is the only colonial I know of who returned to France with his African wife and their children. In his letters to a friend of his who was a notary, Nebout confided his concerns, very personal things… For a reader today, his words might appear racist. In fact, at the time, there were no other words to designate people and their behavior. It could seem racist, but he took his wife, “la belle Ago,” and the children to France. This correspondence inspired me. Based on my reading, I decided to pursue my interest in the letters instead of administrative reports. The book gave me the sound of the Maxime Dabilly’s language and his way of writing and speaking40.

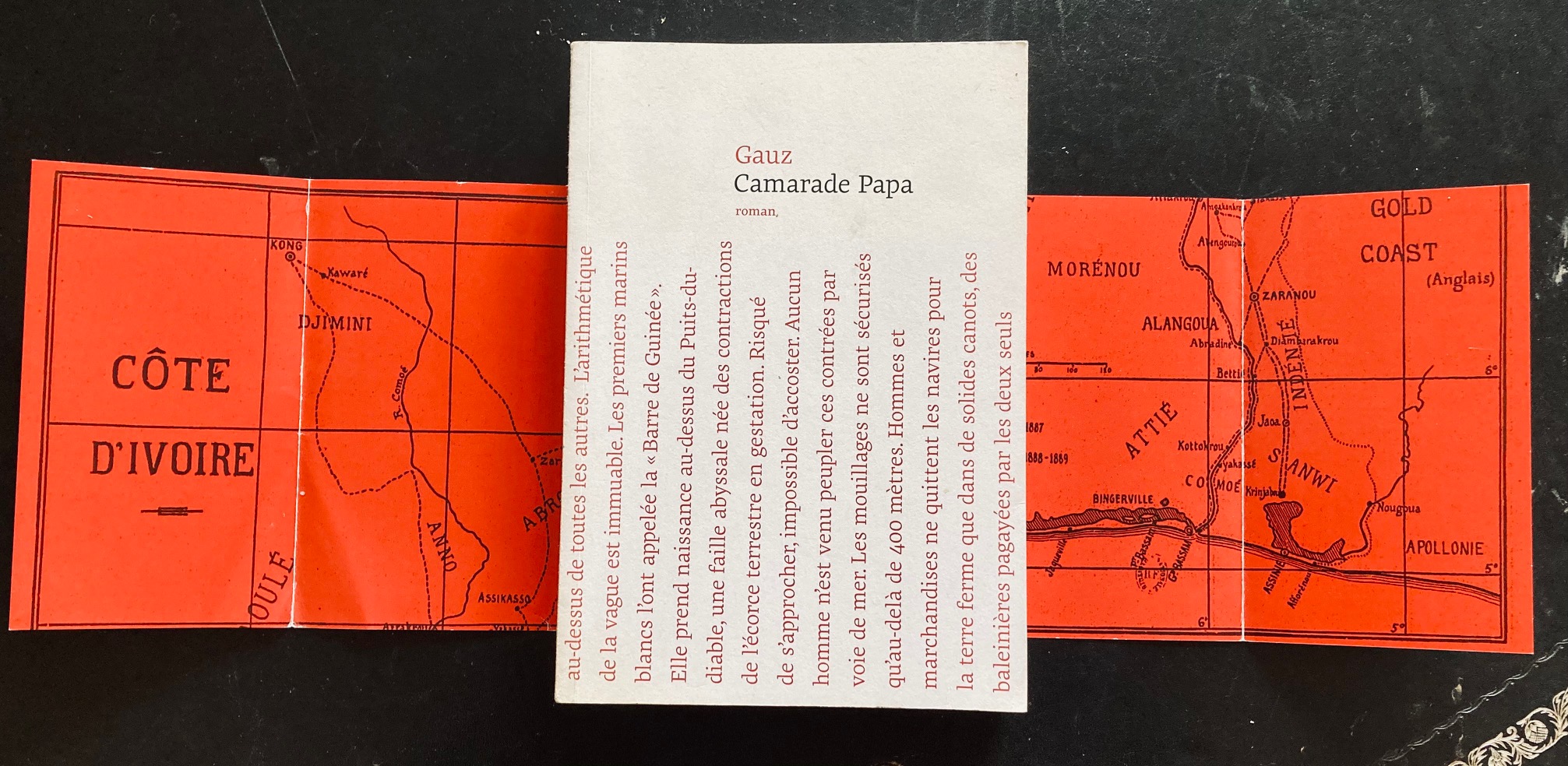

The private Nebout about whom Gauz wrote differs sharply from the characters in the celebrated “romans de la mousso” that were typical of colonial literature. One example is Louis Charbonneau’s Mambu et son amour, in which the protagonist abandons his local wife, dooming her to die of grief after he leaves for metropolitan France41. It is nevertheless important to balance this initial portrait of Nebout, whom Gauz portray only through a harmless silhouette of the colonial in love. Born in Normandy in 1862, Albert Nebout enlisted in the naval infantry after studying pharmacy. He was posted as a soldier in Senegal, where he served as chief of a railway station in Louga. In 1890-1891, he miraculously survived the Crampel expedition in Oubangui-Chari (meaning that he joined the list of colonial heroes celebrated by the candy manufacturer Guérin-Boutron in its “Famous Explorers” series) and later participating in the Mizon expedition in present-day Nigeria. Settled in Côte d’Ivoire, he was responsible for the 1893 negotiations with Samory and served on three occasions as acting governor.

Albert Nebout Medallion in a promotional chromograph series by Guérin-Boutron chocolates.

Nebout encountered the most prominent figures of colonial history during his career, including Maurice Delafosse, Gabriel Angoulvant, and Louis-Gustave Binger42. To believe Gauz, however, the parallel between the fictional Dabilly and the real Nebout is less based on similar professional itineraries than on kindred styles, as well as what might be described as their amorous ethics. Concerning the first point, an attentive reading of the second half of Nebout’s epistolary memoirs, which cover his administrative functions in Côte d’Ivoire, helps to identify echoes in Gauz’ narrative. This includes the moment when the administrator describes the escapades of an Alsatian newcomer, presented as Binger’s cousin, to his correspondent:

Delafosse went on leave. He is a hard worker and the public servant of the future. He writes from morning to evening. He methodically studies languages, and he speaks Baoulé like a Baoulé, with emphasis and nasalization. […] He is replaced by M. M… He is not the same type. Shorter than Delafosse, the new arrival is fatter. He is a solid, blond guy who once served in the Foreign Legion. […] People tell an amusing story about his accent. He was working in Bassam as a schoolteacher. He dictated the following sentence to the little Blacks: “la renard a manché la boule,” [the fox ated (sic) the ball]. And of course, the children wrote boule and not poule [chicken]. And M… exclaimed: “Mais sapristi! Je ne vous dis pas la poule, je vous dis la boule!” [But sapristi, I didn’t say la poule. I’m saying la boule.] The children understood nothing. He didn’t hate humor. From Dabou, where he was chief of the outpost, on July 14th, he sent a small box containing three ducklings painted blue, white, and red to his cousin Governor Binger43.

It is tempting to consider the source of the dialogue between Alsatians referred to earlier in this article, in which a loquacious cousin of Louis-Gustave’s also participated. The reference to what Gauz called a “francité houspillée” [chastised Frenchness]44 in his talk at the Collège de France, a quality shared by colonizers and colonized, and hence a heritage of Nebout’s texts, of which Gauz’ novel suggests a “postcolonial use” by adopting and extending a certain thought. Another feature shared by both texts is the description of rival factions as “negrophiles” et “negrophobes.” Nebout portrayed them as follows:

The role of administrators is, according to my idea, to bring natives to us using proper procedures, and not to distance them with violence and insults. I promised myself that I would always be approachable, affable, patient, and calm, while also being firm and fair. […] In any case, I have never been, and hope never to be, either negrophile or negrophobe. I have known both specimens only too well. The former are often ridiculous and can be dangerous. The latter are odious and incapable of approaching a Black without insulting or mistreating him45.

Maxime Dabilly inherits the laudable concern of not adhering to either camp, and Gauz reinforces his narration reinforces by seating them at different places around a table:

The seating arrangement is invariable: Bricard and Péan along one side, Dejean and Fourcarde facing them, and Dreyfus and me at each end. Fourcade explains to me that Bricard and Péan are négrophiles, the worst sort of white men in the colonies. Péan explains that his friends on the opposite side of the table are négrophobes, the worst sort of white men in the colonies. The negrophobes use “nègres” for men, “négresses” for women, “sauvages” for groups. They say “nègre” with their chins held high and a superior air, emphasizing the accent by lifting a corner of their lips. “Négresse” whistles its final “s,” forming a rictus of concupiscence on their faces. “Sauvage” rounds the eyes and compresses the nose to convoke the image. The négrophiles have a panoply of nominal groups loaded with epithets. “Tirailleurs sénégalais,” “porteurs mandés-dyoulas,” “robuste Kroumen,” “jolie Apolonienne,” “belle Fanti,” “fine Malinké,” “superbe mulâtresse,” “horrible Akapless”… They know the races and do not hesitate to offer generalities. When I was asked my views, I used a mix of references. In medio stat virtus46.

The cleavage between negrophobes and negrophiles is glossed as though it belonged to an established lexicon and sets of expressions and syntagms. While Nebout mentioned insults without giving details, Gauz deploys a more specific vocabulary that he openly associates with an analysis of behaviors and pronunciation, thus forging a link with the lexicographical temptation that led him to write his book Debout-payé in the form of a glossary.

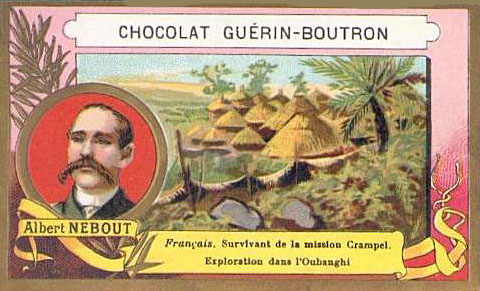

On the second point about the amorous ethics of colonials, it is important to eschew idealizing such figures as Nebout, whose exemplary openness towards racial mixing Gauz explores. Like Dabilly, Nebout reports that his first African wife, Etien, died giving birth. His grief was quickly effaced by his encounter with the beautiful Ago, who quickly joined a procession of local wives. On this occasion, Nebout makes certain that he reminds his correspondent that native marriages are never more than a last resort:

I know you’re interested in my African unions, while also blaming me for exposing myself to graves responsibilities. I understand these fears, but what do you expect, you cannot resist nature and on the other hand, you can’t bring a French woman to these unhealthy countries. So, you have to resign yourself to local unions. […] My wife Etien, pregnant, went to Touniané, and she died during childbirth five months ago. I was aggrieved, I assure you. And I felt remorseful for not having shown more affection to this little, well-behaved négresse. In spite of frequent incidents that I will relate to you, I was bored alone in my big hut, and I resolved to get married47.

While Gauz’ Dabilly character is delighted that his newborn child has “black skin” and “rust-colored curls,” Nebout, who is similarly polygamous, is far more suspicious about his many offspring. With no particular emotion, he relates what befell the child of one of his wives, Agua:

I received a surprise. I didn’t write you that Agua had delivered in Tiassalé. The messenger came to me with the news and seemed embarrassed to describe the child’s color. On a trip I took to Tiassalé, I had him introduced to me and instantly turned away: the child was of the deepest black. I refused to see the mother, and that was the end of it. […] A few weeks before my departure, I learned that the child had died, having struck his head a root after falling off his mother’s back. I asked myself several times if it was really an accident48.

The child’s skin color had immediately aroused his suspicion that his mother had been unfaithful. Nebout accused her of being married to another man and, as this cruel anecdote suggests, the newborn’s “handsome black” skin was tantamount to a death sentence. The situation was different a year later when Ago introduced a child to Nebout, who had returned from an expedition:

After eight days of somewhat difficult travel on horseback because the rivers were still flooded, we arrived in Guiguewi. Scarcely had I descended from my horse when I saw my little Ago coming towards me holding a completely naked baby in her arms whom she gravely presented to me. I embraced mother and child without shame. She was a little girl of three months. There can be no doubt that I am a jeweler: my baby, whose skin was scarcely tinted with yellow, was adorable. She had a Baoulé name that I found lovely: Aya49.

The girl’s faintly golden skin appears to constitute a decisive argument that allows her father to unashamedly embrace and publicly acknowledge her, as he did with the other children that Ago carried.

Ago with one of her sons (Albert). Photograph from family archives, reproduced in Passions africaines.

The fate of Adjo, Dabilly’s lover, differs significantly from that of Etien, who died, repudiated, in childbirth, or Agua, repudiated, or even Ago, who is taken back to France after the end of her husband’s career. Gauz’ hero does not entirely mimic Nebout’s ambiguous position, but instead represents at most a stylized version that is largely stripped of contradictions. The choice of simplifying the postcolonial representation of racial mixing in colonial times is far from the subtlety with Gauz that it achieves with the Congolese author, Henri Lopes, himself mixed-race and the author of several novels that explore problems encountered by mixed couples50.

The historical character Treich, whom Gauz represents in an essentially positive light, was also involved in the paradigm of colonial love. Indeed, the novelized description of the couple in Camarade Papa suggests that he had a latent homosexual relationship with his interpreter, Louis Anno, if not merely a form of homo-erotic temptation:

The Resident of France is of above-average height. He has short hair, chestnut-brown hair, and pleasing features. His quasi-feminine beauty is reinforced by the absence of a beard, even though he sports a fashionable, right-bank, Châtellerault moustache. Standing at the center of the circle formed by his hands in the pockets of his blouse, he spoke slowly, gazing at each of us in turn51.

Sailor hat with a pompom, pipe clenched in his teeth, plaid shirt, loincloth around his waist, walking shoes, a black with the air of a Scottish laird appeared. He had a troublingly androgynous beauty and a strong, muscular body. The discomfort was accentuated by his imposing voice and well-trained, accentless speech. […] Treich introduced me to his interpreter, Louis Anno. Their salutations were warm. They spoke as if I was not there52.

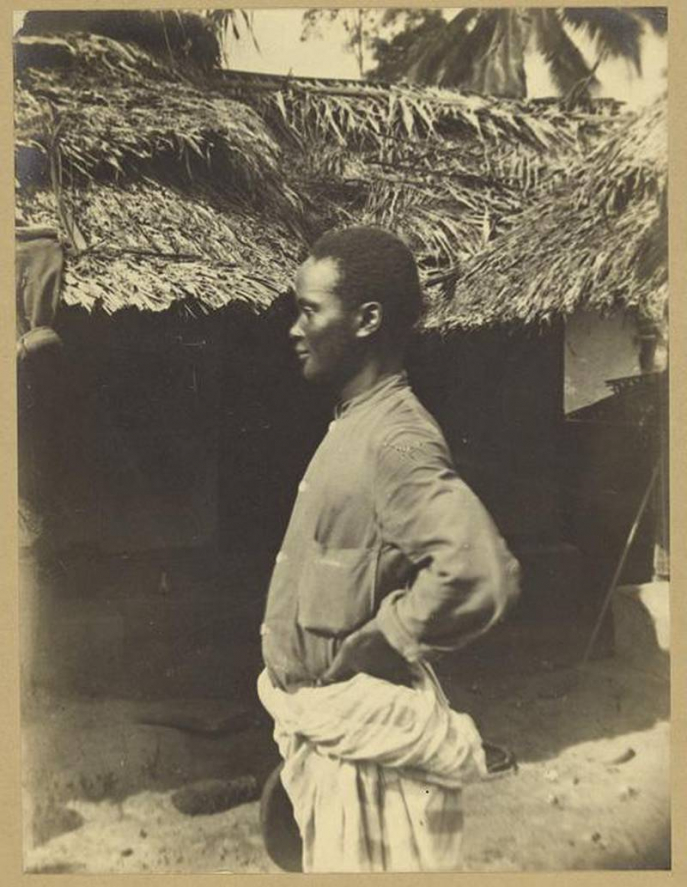

Louis Anno, whose signature appears on the treaty between Captain Binger and the Chief of the State of Diammala (1892), is depicted as Treich’s African alter ego, with harmonious features and an almost effeminate presence. This mimetic desire to unite the colonial official with his interpreter appears to an authorial invention. It is not mentioned by contemporary observers, although some do mention that Louis Anno tended to “take on European airs.” As for the photograph taken of him during Binger’s travels, there is no sign of the coquettish accessories described by Gauz. While the interpreter did wear a shirt bound at the waist by a rolled loincloth, there is no trace of the pipe or pompom.

Portrait of Louis Anno by Charles Monnier, 1892.

It also seems probable that the portrayal of an androgynous Louis Anno stems from the preciousness and hypercorrection of his language, emphasized by the photographer, Marcel Monnier, who mocked Anno’s “oratorical precautions” and “prud’hommesques [pretentious] paraphrases”53. Gauz, then, transposed this essentially linguistic portrait of Louis Anno to offer an image, not of the often-mocked scholarly air of early “écrivains-instituteurs” [writer-teachers]54, but of traits associated with a precious, effeminate figure. Beyond the stereotyping of this representation, this specific, regrettable hypothesis is neither developed nor explained in the novel. Nor is there any reference to Anno’s fate after Treich’s death or his subsequent employment as Binger’s interpreter. Indeed, the novel abandons this brief foray into a form of postcolonial rewriting of colonial history.

“Chance or Coincidence”: A Few Echoes of Monénembo

Nebout’s correspondence, described by Gauz as one of these “incredible books […] that exist nowhere else55”, is not the sole source of inspiration for the colonial facet of Camarade Papa. Indeed, this is not the first time a postcolonial writer projects himself onto a main character who is a colonial. Indeed, this device was employed by the Guinean author Tierno Monénembo in his 2008 novel, Le Roi de Kahel, which won the Renaudot Prize.

Tierno Monénembo, Le Roi de Kahel, cover of paperback edition.

Although the characters of the two novels bear no resemblance – and for good reason, given that their exploits occurred in different regions of West Africa –, there are striking similarities between the two novels. Both depict setbacks faced by Western explorers, whose bodies are weakened by fever and dysentery and who face harsh challenges during their incursions into African territory. Both remind us of the historiographical clichés surrounding the rivalry between the French and the English that caused a race for treaties and anguished speculation about the progress of the opposition’s explorers. It is also possible to trace a parallel between two dialogues in which Franco-British competition tilts against Englishmen, who are at a disadvantage among local populations because their names are so difficult to pronounce:

“The friendship that France offers us is a friendship of oil and water, with one on top, the other on the bottom,” grumbled the king of Fogoumba.

“At least he has a few rifles,” joked Pâthé. “But they’re for shooting grouse. He’s never fired at a Fulani.”

“He came to our home as a friend!” agreed Bôcar-Biro.

“Whereas this Englishman with an unpronounceable name brought an army!” added Alpha Yaya56.

“The English arrived exactly seven days after Treissy’s departure. Their leader’s name was Captain Lèf… Lèfy…

“Lethbridge.”

“Exactly! Allah is merciful to make mouths that are able to pronounce such a name.”57

More fundamentally, at the heart of both narratives is an impassioned explorer figure who, because they are not full members of the colonial apparatus, are gradually moved from center stage onto the sidelines of history. According to Gauz’ narrative, Binger’s imminent arrival is repeatedly framed as a danger for Treich, who hears the following prophecy:

You told us that you were going to look for your white brother. The fetishes are unanimous: Do not return with him. If you find this man, put him to death. Next, cut off small bits of anything that sticks out—hair, nails, nose, genitals—and throw them in the first river that blocks your way. […] If you aren’t strong enough, abandon him! He will die like lost white men die here, delirious with fever and laying in pestilential puddles of diarrhea. If you bring him to the coast, this man will devour your soul and you will disappear without descendants58.

The prediction comes true, and Treich dies after he brings Binger to the coast, leaving him the historic privilege of having “given Côte d’Ivoire to France,” as his tombstone recalls. At the last minute, the soldier replaced the adventurer, who was condemned to the oblivion of memory. The same takes place in Le Roi de Kahel, in which the industrialist Aimé Olivier de Sanderval, who is planning to build a railway in Fulani country and seeks to sign treaties with local chiefs. He is replaced by men sent by the colonial government, particularly the first governor of French Guinea, Doctor Noël Ballay. Indeed, the main character himself emphasizes the irreducible dichotomy between two men of imagination and two others who are part of the system:

Now, we must build. Institutions, of course, but above all roads, and buildings, both for the government and for men like him who are unbowed, imaginative, and ambitious. And for that, we didn’t need to complicate the idle lives of office clerks and parliamentarians. […] Who had made America? Pioneers, of course, and not paper-shufflers in Washington!59

Sanderval is wrong in imagining that Africa will become the chosen land of free and imaginative men, of whom he considers himself a paragon: he is evicted from his “kingdom” by Ballay, who views him as “a mythomaniac scumbag” and thinks it is impossible for “his colony to succeed” in the presence of such a nuisance60. A further insight in this intertextual comparative study is that Gauz and Monénembo’s unfortunate heroes both dream of settling in Africa in strangely similar ways. Dabilly, describing the compound he has had built in Assikasso as “my Versailles61”, is part of an irony-laced dream that is shared by Monénembo’s Sanderval:

No, it wasn’t the Château de Versailles, but amid bamboo and vines, it looked a bit like it, with a splendid colonial house cluttered by staircases and balustrades and a vast garden gently sloping toward the softly splashing sea62.

Both heroes witness the inexorable collapse of their “African châteaux”: Gauz and Monénembo both chose a point of view that could be thought of as “unhappy colonials” who are disdained or destroyed by the imperial machine. Under these circumstances, slipping into the skin of Sanderval or Dabilly, Treich’s fictional companion is not the same as rewriting “the history of the winners,” but instead approaches it from a postcolonial angle that is neither that of the conquerors nor of colonized peoples. The rehabilitation of these strange “vanquished” colonials in both books relies on astoundingly similar historical comparisons. In Le Roi de Kahel, Tierno Monénembo attributes to Olivier de Sanderval an analogy between the struggle of the intestinal struggles that traverse Fulani principalities and the bloody sixteenth-century rivalry between King Henri III and the Duc de Guise:

On May 10, tired of trying to sleep, he pulled out his pencil and wrote down this prophecy: “My little finger tells me that this country is readying itself to play again, and in a similar scene, two sad episodes of the history of France…On one side, the Armagnacs, and on the other, Burgundians! On one side, Timbo. On the other, Labé! Each of these abysses sheltering a Henry III and a Duc de Guise! Here Pâthé and Bôcar-Biro, there, Aguibou and Alpha Yaya!... Curious Fouta! These Fulani are sharp, perhaps too sharp!63”

Gauz introduces a similar comparison between the Agny Princess, Malan Alloua, and Catherine de Medici, who, it is worth recalling, was King Henri III’s mother:

Malan Alloua bears some resemblance to Catherine de Medici. Both have graceless traits. They know how to play the poisoned vial. Numerous enemies at court have tasted their specialties and died. Each is as sanctimonious as the other and is willing to use their firm religious convictions towards bloody methods to settle divergences of opinion about the sacred. The Europeans tricked heretics in their thousands, scrawled a Saint Bartholomew in letters of horror, soaked in Protestant blood. The African is assiduous at fetish ceremonies that require accessories taken from human anatomy. Alive or dead, there are no taboos on her collection methods64.

Both books compare local royalties’ torments with celebrated episodes of French history, an implicitly effort to contradict the stereotype of an Africa without history, or rather of an Africa whose history began only with colonization.

The many common points between Gauz’ and Monénembo’s books indeed suggest a hypothetical intertextuality that, unlike those between Gauz and Romain Gary in Demain j’aurai vingt ans and with Alfred Nebout’s letters, remains studiously unacknowledged. Indeed, while Gauz willingly pays homage to Alain Mabanckou, whom he describes as a big brother and a source of inspiration, he makes no mention of Monénembo’s novel, which is nevertheless a latent reference of his narrative’s predominantly colonial aspect. This exemplifies the secretive intertextuality referred to by Jean-Louis Cornille65, who contends that every author has a collection of acknowledged sources as well as a single, tacitly foundational source. It is therefore the responsibility of the critic to function as a “scientific detective” to uncover the hidden underlying text that is the true focus of his work. In the case of Camarade Papa, this literary investigation leads to the conclusion that references to Gary, Mabanckou, and Nebout are deliberately misleading clues intended to camouflage the substantial influence of Monémembo’s novel on Gauz.

This does not encompass the inspiration drawn from colonial-era texts, an approach that both authors share. Monénembo’s method appears both richer and more rigorous than Gauz’ approach, however. Unlike Gauz, who makes no mention of Nebout in the body of his narrative or even in the preface, dedication, or notes, Monénembo explicitly declares his reliance on the archives and offers thanks to the Sanderval family and the staff of the Archives départementales in the French city of Caen. In an article examining intertextualities between Le Roi de Kahel and the narratives of Olivier de Sanderval, Florence Paravy demonstrates that this rewriting requires a form of literary adaptation that combines faithfulness to the original with liberties such as additions and occasional deletions66. Monénembo pairs his literary exploitation of archives with a reflection on the stakes surrounding colonial writing, which is presented as the Romanesque counterpart to triumphal positivism:

By coincidence, our future King of Africa corresponded nicely to the Bantu proverb that says, “We are more the sons of our epoch than of our fathers.” He was the spitting image of the little man of the 19th!... Ordem et progresso!... His education, his temperament, everything prepared him to vibrate with the passions of his century. Ideas, sciences, great voyages. He had been imbued with a pioneer mentality, amid a century of pioneers! He had envisioned life from early on as a steep staircase stretching towards exploits. Heroes had their legends, and the obstinate quest for greatness and plenitude would have its book. And that book would be called L’Absolu, the sum of his thoughts, the fusion of every parallel, of the idea and life, the real and the void, being and God. Begun when he was twelve, this modern-day Métaphysique was now in its twentieth draft. René Caillé had left travel journals, but he would leave a logbook, as well as a way of thinking; it would be a lyrical work, but also an encyclopedia67.

Described as a child of his century, Olivier de Sanderval dreamt of himself not only as a pioneer of new lands, but also as a writer, the author of an ambitious work endowed with a hybrid form and a totalizing will. It is more than a logbook--it is a philosophical treatise and a poetic tome combined with an “encyclopedia” that he imagines himself writing. The various metaliterary reflections in Camarade Papa are far from this conceptual level and critical value. Of course, Maxime Dabilly periodically mentions activities related to writing, but their sole motivation is to obey the imperative to bear witness, not to achieve a totalizing work:

All of my observations about the Agnys of Assikasso, I consign to a notebook. The written report is the colonial’s obligatory exercise. Treich even believes it to be his most imperious duty. He imposes it on himself every evening. “You see, Dabilly, our existences here are so fragile that we must conceive of our presence as a relay race. The report ledgers are their only records68”.

Gaining in constraint what it loses in panache, the writing is limited to keeping track of the adventures “in anima vili69”. Even Nebout’s text was not immune to literary pretentions and reflections on the form that a colonial narrative should adopt. Below is an example, a brief passage about adventure novels and their pleasing contrast to the insipid life of the “bushman70” in office:

How grateful I am to you for the books you have sent me, adventure novels that I love so much; I read them during siestas while awaiting the true adventures that, I hope, will someday come. In the meantime, life is monotonous!71

If Camarade Papa does in fact constitute a rewriting of Roi de Kahel in the sense proposed by Jean-Louis Cornille, the apostle is clearly lesser than the model, either in terms of the rigor of archival work or the quality of the literary contemplation of the imperial experience. In standing tall to nourish the postcolonial memory of the colonial, Gauz intelligently adopts an approach that had already earned Tierno Monénembo a prestigious literary prize. By introducing a second plot that centers on the character of Anuman, it reinforces the postcolonial dimension of a narrative sprinkled with communist rhetoric, while also winking at the colonial uses of the “petit nègre.” This addition, however, itself borrowed from other authors, does not suffice to counterbalance the relative anemia of the colonial intertext, whose historic and literary tenor remain relatively weak. Invoking historical figures such as Treich and Louis Anno is ultimately too fleeting to allow a true incarnation, while Nebout’s text is amputated from its more ambiguous sections, probably of most interest to contemporary readers. The writing itself inherits a certain tendency to “bad writing” that is only partly justified by the pretense of a childhood narrative. Dabilly’s notebooks, unlike Sanderval’s, do not aspire to become literary works. They are ultimately daily note-taking that does not even adopt the epistolary form of Nebout’s chronicles. Ten years later, in sum, the itinerary of the adventurers of the empire, decidedly spoiled by literature, continues to motivate authors, but the profundity of the postcolonial narrative about the colonial has not uniformly improved.

“All This for That?”: La francophonie in the Gut

In guise of a conclusion, I would like to quickly discuss another francophone novel that attracted even greater attention than Camarade Papa during the autumn literary season of 2018. This detour seems necessary to me to illustrate a phenomenon of rewriting and recovery that, although not systematic, nevertheless appears typical of contemporary francophone literary production, constructed by “rewriting” earlier texts. These works belong to the domains of archives or literary history. In this centenary year, David Diop’s brief story, Frère d’âme, is coincidentally dedicated to the gesture of le tirailleur sénégalais72.

David Diop, Frère d’âme, cover of paperback edition.

The story relates how Alfa Ndiaye, who witnessed his friend Mademba Diop’s death, a friend with whom he shared kinship based on humor, but somber in a murderous insanity that led him to in spite of himself to confirm every cliché of the bloodthirsty ferocity of African soldiers. A former master in cutting off the hands of Germans whom he had already disemboweled, Alfa Ndiaye is ultimately sent to a hospital for psychiatric treatment. The novel’s second section focuses on this cure, alternating between African reminiscences that lead the sharpshooter to recall memories of his mother or of his first lover, as well as inspired in the bedridden soldier by the doctor’s daughter. In one of the final scenes, Alfa Ndiaye enters the daughter’s bedroom to relieve the desire that she provokes in him and, in attempting to stifle her protests, he ultimately suffocates her.

Although located in an entirely different historical period, Diop’s narrative, which won the French Goncourt des Lycéens prize, share a number of important points with Gauz. Summoning a vast repertoire of clichés and stereotypes, he draws on simple language that attempts to imitate, not childish language, but an approximate tirailleur dialect. From the literary angle, he is less successful in evoking forgotten ways of speaking than in constituting a literary “petit nègre” replete with syntactic shortcuts and repetitions. While the reinvention of this language unquestionably counts as a postcolonial use of the colonial, the study by Cécile Van den Avenne invites criticism of an extreme syntactic and lexical simplification that, while providing authors with a somewhat facile literary device does not reflect the tremendous diversity of colonial language varieties:

The oral usages of French learned outside the school setting by illiterate Africans, at least in French […] were without the least doubt far more varied than what was revealed by the highly stereotyped representations of le français-tirailleur73.

David Diop’s narrative also relies on rewritten, simplified literary references. The young woman’s murder powerfully recalls the scene in the novel Native Son by the black American writer Richard Wright, in which Bigger Thomas assassinates a young woman named Mary Dalton74. Although their consequences are similarly dramatic, the two situations are fundamentally different: whereas Alfa Ndiaye gives in to a savage, all-consuming passion that leads him to commit a violent crime, Bigger Thomas does not suffocate Mary merely because of fears of being caught in her room and accused of rape, but by virtue of the stereotypes that make the black man a sexual predator who is perpetually on the hunt for white flesh. One character kills voluntarily by raping, and the other kills involuntarily out of fear of being unfairly accused. Unlike Wright’s story, David Diop’s narrative does not show a man trapped by clichés, but indeed by their repeated incarnation. This discreet rewriting of an African American novel could help shed light on the remarkable trans-Atlantic reception of Frère d’âme, including the Man Booker Prize in 2021 for David Diop, the first French author to win the prize. This can also be understood as the manifestation of a memorial duty towards colonial soldiers and implicit recognition of a filiation between an American novel published in the midst of World War Two and a contemporary francophone narrative.

Two conclusions come to mind as we near the end of this literary study centered on Gauz’ Camarade Papa, which is positioned – thanks to its author’s success – as a representative work of contemporary francophone African literature. The first of these insights concerns the links between these literatures and history, most especially colonial history. The return to the period of imperial conquest or the participation of African soldiers alongside French troops in the First and Second World Wars, unquestionably constitutes a “postcolonial usage of the colonial” by francophone African authors. Recognized by prestigious literary prizes, this usage could even be described as strategic and is consistent with the imperatives of memory and repair75 and gaining national and international recognition for the authors, particularly in the West.

The question that then arises is whether this postcolonial persistence of the colonial is not in danger of drifting towards purely instrumental uses that treat narratives as seamlessly marketable commercial products rather than full-fledged literary works or historically grounded reflections. I have suggested that in this book, the answer to this question lies in the genealogy of francophone letters, following Jean-Louis Cornille and Anthony Mangeon, conceived of as a system of echoes and rewritings. Comparing Monénembo and Gauz’ novels, as well as those of Diop and Richard Wright, clearly brings to note the durability of a postcolonial use of the colonial, but also of a certain distancing effect or weakening of the original narrative. The archive is increasingly distant and decreasingly referred to. On the other hand, the simplifying force of stereotype imposes itself with renewed vigor. The risk is all the more explicit in that the diagnosis suggested by Mongo Beti at the end of the last century appears all the more valid today: contemporary African literature, submitted more to the judgement of the media than to academics, tends to be viewed as a perpetual novelty that is detached from its own history, simultaneously postcolonial and colonial, and henceforth rich in masterpieces.

For this reason, I have attempted to take the opposite position here by striving to show how much recent francophone literary works have inherited from earlier works. As well as the potential loss of substance and literary quality that has been encouraged by commercialism or thoughtful literary and editorial strategies. At first sight, such observations assuredly do not constitute a plea for novelty or the existing literary system. As early as 1950, Julien Gracq deplored the proliferation a “literature of the gut,” i.e., a woeful tendency on the French literary scene, and to an even greater extent, of criticism, to become enamored of recently published texts that are solely celebrated for their novelty:

The overbearing demands of great writers makes almost every new arrival [on the literary scene] appear to come from a hothouse: he dopes himself; he labors, he thrashes his ribs. He seek to be equal to what is expected of him, equal to his epoch. As for the critic, he does not want to let go, regardless of cost he will discover. It is his mission—this is not a period like the other – each week, he must have something to throw into from his horn: a Tahitian philosopher, a convict’s graffiti – Rimbaud redivivus. Sometimes he looks like a frightened trumpet that blares at everything out of fear of missing something, amid the ritual, colorful fiesta that our “literary life” has become: the exit of the racing bull and the picador’s horse76.

Surely, we must acknowledge that “the [present] epoch,” defined by the postcolonial turn, in indeed an epoch unlike others – if only because it does not authorize the advent of new, innovative voices that have emerged from former colonies to impose an undeniable duty of memory and repair. This situation does not justify, however, for francophone African literature – which the Congolese writer Sony Labou Tansi described as written “from the gut77” – the visceral link to the “interior country,” or being reduced to little more than a “literature of the stomach” in pursuit of prestigious Parisian and international distinctions, henceforth disconnected from its original continent. In order to better pay homage to the creations of African authors and help them become part of literary history, let us ensure, then, as best we can, that we follow the model offered by the African adventurer Sam Lion, whom Claude Lelouch brought to the big screen: Facing a seemingly innovative work, let us read further, expand our knowledge of francophone literatures. Let us enter into their fabrication and, above all, let us not appear to be too “astonished.”

Notes

1

Founded in 2009 at the initiative of Benoît Virot and Frédéric Martin, the Attila workshops split in 2013 to form Le Nouvel Attila and Le Tripode.

2

Maryam Madjidi, Marx et la poupée, Paris, Le Nouvel Attila, 2017.

3

Gauz, Debout payé, Paris, Le Nouvel Attila, 2014. The novel came out in paperback in 2015.

4

“Les dix ans”, in Gauz, Camarade Papa, Paris, Le Nouvel Attila, 2018, p. 254.

5

Claire Ducournau, La Fabrique des classiques africains. Écrivains d’Afrique subsaharienne francophone, Paris, CNRS Éditions, 2017.

6

See Claire Ducournau, “Une visibilité à négocier: ‘Monde noir’ and ‘Continents noirs,’ deux collections françaises de littérature africaine”, French Cultural Studies, vol. 30 (2), no. 138-152, p. 144-145.

7

The “manifeste pour une littérature-monde en français” [manifest for a world literature in French] was published on 16 March 2007 in Le Monde. Signed by forty-four French-language authors, the text recommended transcending the cleavage between French writers and francophone writers. It resulted in the publication of a mult-authored book that was edited by Michel Le Bris and Jean Rouad (Pour une littérature-monde, Paris, Gallimard, 2007).

8

Anthony Mangeon, “Qu’arrive-t-il aux écrivains francophones? Alain Mabanckou, Abdourahman Waberi et le manifeste pour une littérature-monde en français”, in Jean Bessière, Joanny Moulin, and Micéala Symington, Actualité, inactualité de la notion de “postcolonial”, Paris, Champion, 2013, p. 105-129, here, p. 129. Here, Mangeon is referring to the Malian author Yambo Ouologuem, whose first novel, Le Devoir de violence, was initially very favorably received and won the Prix Renaudot before he was accused of plagiarism. In a satirical anthology entitled Lettre à la France Nègre, Yambo Ouologuem defended himself by arguing that borrowing is a literary practice. See Yambo Ouologuem, Le Devoir de violence, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 1968 and Lettre à la France Nègre, Paris, Éditions Edmond Nalis, 1969. The opposition between “littérature puissance” [power literature] that grapples with history and “littérature joujou” [toy literature], which is more inclined to use well-worn literary techniques and themes, originated with Jean Bessière, Qu’est-il arrivé aux écrivains français? D’Alain Robbe-Grillet à Jonathan Littell, Loverdal, Labor, 2006.

9

Bernard Mouralis, “Qu’est-ce qu’un classique africain?”, Notre Librairie, 160, December 2005-February 2006, p. 34-39, here p. 37. See also Mongo Beti, “Conseils à un jeune écrivain francophone”, Peuples noirs, peuples africains, 8e année, no. 44, March-April 1985, p. 52-60.

10

Tierno Monénembo, Le Roi de Kahel, Paris, Le Seuil, 2008.

11

Jean-Louis Cornille, Chamoiseau…fils, Paris, Hermann, 2013, p. 64.

12

Regarding Arthur Verdier’s comptoirs [trade establishments], see the fictionalized biography by Yvon Marquis: Arthur Verdier, une ambition africaine, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2013.

13

Gauz, Camarade Papa, Paris, Le Nouvel Attila, 2018, p. 44-45.

14

Gauz, Camarade Papa, Paris, Le Nouvel Attila, 2018, p. 241.

15

I use the term in its historical sense to refer to a period after colonization.

16

Gauz, Camarade Papa, Paris, Le Nouvel Attila, 2018, p. 241.

17

Gauz, Camarade Papa, Paris, Le Nouvel Attila, 2018, p. 251: “The papers, he’s the one who wrote a bunch of stories about them. First in his own hand, like Maman. Later with the machine. I like the stories a lot. I’ll read every page on the ancestor-stones.”

18

Jean-Loup Amselle, L’Art de la friche. Essai sur l’art africain contemporain, Paris, Flammarion, 2005. In this critical work, Jean-Loup Amselle reveals the way in which contemporary African art responds to its Western promoters and buyers, needs a primitivist revival. See in particular p. 88, in the context of the chapter “Primitivisme et postcolonialisme”: “The African child – and that is why he occupies such an important place in the Western imagination – through his dual nature of child and African and the promise of a rejuvenation of our tired world.”

19

Anthony Mangeon, “La construction du lien social dans les romans d’Alain Mabanckou”, Revue de l’Université de Moncton, vol. 42, no. 1-2, 2011, p. 51-64.

20

I use the term “posture” in the sense defined by Jérôme Meizoz to refer to a construction of the individual history of the writer based on both the text and the paratext. See J. Meizoz, Postures littéraires. Mises en scène modernes de l’auteur, Geneva, Slatkine, 2007. See also, in the field of francophone literatures: Anthony Mangeon (ed.), Postures postcoloniales. Domaines africains et antillais, Paris, Karthala, 2012.

21

Marianne Payot, “Mots et maux d’Afrique par Mabanckou et Gauz”, L’Express, 27 August 2018.

22

See, for example, Alain Mabanckou, “Le chant de l’oiseau migrateur”, in Michel Le Bris and Jean Rouaud (Eds.), Pour une littérature-monde, Paris, Gallimard, 2007 and Écrivain et oiseau migrateur, Brussels, A. Versaille, 2011.

23

Léopold Sédar Senghor, “Poème liminaire”, in Hosties noires (1948), Œuvre poétique, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 2006, p. 57.

24

Émile Ajar, La Vie devant soi, Paris, Le Mercure de France, 1975. The actual identity of Émile Ajar, who was none other than Romain Gary, was revealed only after his death in 1980.

25

Alain Mabanckou, Demain j’aurai vingt ans, Paris, Gallimard, 2012 [2010].

26

Alain Mabanckou, Les Cigognes sont immortelles, Paris, Le Seuil, 2018.

27

See the recent edited volume by Maria-Benedita Basto, Françoise Blum, Pierre Guidi, Héloïse Kiriakou, Martin Mourre, Céline Pauthier, Ophélie Rillon, Alexis Roy, and Elena Vezzadini, Socialismes en Afrique, Paris, Éditions de la Maison des sciences de l’homme, 2021. See also the special issue of Cahiers d’études africaines on “élites de retour de l’Est” [elites returned from the East] (no. 226, 2017).

28

Gauz, Camarade Papa, Paris, Le Nouvel Attila, 2018, p. 58.

29

On this subject, see Cécile Van den Avenne, De la bouche même des indigènes. Échanges linguistiques en Afrique coloniale, Paris, Vendémiaire, 2017, particularly the chapter “De l’authenticité du petit-nègre,” p. 139-162, here p. 142.

30

Ahmadou Kourouma, Les Soleils des indépendances, Paris, Le Seuil, 1970 [1968].

31

Sony Labou Tansi, La Vie et demie, Paris, Le Seuil, 1979.

32

Gauz, Camarade Papa, Paris, Le Nouvel Attila, 2018, p. 22.

33

Gauz, Debout-payé, Paris, Le Nouvel Attila, 2014.

34

It would be interesting to consult the publication that followed the first season of Ateliers: Achille Mbembe & Felwine Sarr (eds.), Écrire l’Afrique-monde, Paris-Dakar, Philippe Rey-Jimsaan, 2017.

35

I take the liberty of referring readers to my essay, Ninon Chavoz, Inventorier l’Afrique. La tentation encyclopédique dans l’espace francophone subsaharien des années 1920 à nos jours, Paris, Champion, 2021.

36

Africa was long known as a terra incognita that remained full of cartographic “blanks.” See, for example, David Van Reybrouck’s portrait of the Congo in Congo, une histoire, Arles, Actes Sud, 2012, p. 67.

37

Gauz, “Les rêves de Kong de Binger”, in Alain Mabanckou (ed.), Penser et écrire l’Afrique aujourd’hui, Paris, Le Seuil, 2017, p. 182-183. Gauz’ lecture is available on the site of the Collège de France.

38

Gauz, Camarade Papa, Paris, Le Nouvel Attila, 2018, p. 221-222.

39

Gauz, Camarade Papa, Paris, Le Nouvel Attila, 2018, p. 75-76.

40

Natalie Levisalles, “Entretien avec Gauz”, En attendant Nadeau, no. 64, published on 9 October 2018.

41

Louis Charbonneau, Mambu et son amour, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2014, with an introduction by Roger Little and a preface by Raymond Escholier [first edition, 1930].

42

This information was gleaned in the volume of letters published in 1995: Albert Nebout, Passions africaines: récit, Geneva, Éditions Eboris, 1995, with an introduction by François Boirard and Claudine Dauba.

43

Albert Nebout, Passions africaines: récit, Geneva, Éditions Eboris, 1995, with an introduction by François Boirard and Claudine Dauba, p. 205-206. Cécile Van den Avenne also recalled Binger’s “bilingualism.” Binger continued to speak Alsatian throughout his life, even in Africa. See Cécile Van den Avenne, De la bouche même des indigènes. Échanges linguistiques en Afrique coloniale, Paris, Vendémiaire, 2017, particularly p. 29.

44

Gauz, “Les rêves de Kong de Binger”, in Alain Mabanckou (ed.), Penser et écrire l’Afrique aujourd’hui, Paris, Le Seuil, 2017, p. 187: “Savorgnan de Brazza isn’t from Loir-et-Cher. Here’s another one with chastised Frenchness. All these people, all these newcomers whose Frenchness is blurred, who brought the Empire to all of France, and we never talk about.”

45

Albert Nebout, Passions africaines: récit, Geneva, Éditions Eboris, 1995, introduced by François Boirard and Claudine Dauba, p. 169.

46

Gauz, Camarade Papa, Paris, Le Nouvel Attila, 2018, p. 89-90.

47

Albert Nebout, Passions africaines: récit, Geneva, Éditions Eboris, 1995, introduced by François Boirard and Claudine Dauba, p. 189.

48

Albert Nebout, Passions africaines: récit, Geneva, Éditions Eboris, 1995, introduced by François Boirard and Claudine Dauba, p. 199.

49

Albert Nebout, Passions africaines: récit, Geneva, Éditions Eboris, 1995, edition presented by François Boirard and Claudine Dauba, p. 230.

50

See in particular Henri Lopes, Le Chercheur d’Afriques, Paris, Éditions du Seuil, 1990. Regarding mixed and domino couples in the work of Henri Lopes, see also Anthony Mangeon, “Structurations et figurations du couple dans l’œuvre romanesque d’Henri Lopes”, in Céline Gahungu and Anthony Mangeon (eds.), Henri Lopes, nouvelles lectures façon façon-là, Fabula/Les colloques, article published on 2 November 2020.

51

Gauz, Camarade Papa, Paris, Le Nouvel Attila, 2018, p. 108.

52

Gauz, Camarade Papa, Paris, Le Nouvel Attila, 2018, p. 113-114.

53