Œuvre de Kouka photographiée à Vitry-sur-Seine, le 28 janvier 2017.

This article1 takes its starting point with my entry quite some time ago as an historian into the world of anthropology in the early 1960s. In many respects it was an entry into a new world, and not always a comfortable one. These were the days that anthropologists still looked down on history as particularizing and therefore “not scientific”. One of my new colleagues at the anthropology department of the Free University (Amsterdam), told me that he did study “social change” but that this was NOT history. And, indeed, many of the classical anthropological monographs we had to read did have a chapter on “social change” but always the last one, more or less separate from the core chapters of the book about a society in some sort of stasis – which went against the grain of what I learned as a historian. From my side I was surprised by anthropologists’ quest for pure, authentic forms which sat again uneasily with what I learnt as a historian – namely what a satisfaction it could give to show that things were NOT what they seemed to be, and that discovering ambiguity was the mark of good research.

However, soon things started to change. By 1970 many of my new colleagues agreed that anthropology was “in crisis” and I noted with pleasure that “social change” was no longer mentioned as an alternative to history. Indeed, in the 1970s many anthropologists wanted to be recognized also as historians (even though the later were not always impressed by the way these new kinds of anthropologists undertook occasional foraging in the archives). At the same time I noted – one of the reasons to stay with my choice for this discipline – the emergence of new terms in current anthropological discourse: attention seemed to switch from notions like “traditional,” “culture” or “social order” to “hybridization”, “ambiguity”, and “incompleteness.”

My inspiration for this article is that, in retrospect, this move to more historical and therefore less fixed views seems to have been a relatively short intermezzo. Are we witnessing a return of purity in the discipline? The increasing popularity of a heavy notion like ontology is for me a sign on the wall. No one less than Marshall Sahlins announced in 2013 (in his foreword to the English translation of Philippe Descola’s Beyond Nature and Culture) the “ontological turn” as a “…radical change in the current anthropological trajectory – a paradigm shift if you want – that would overcome the present analytical disarray…” Of course, ontology is now so much in fashion that this turn covers a wide scala of directions and ideas, which makes also that it can be easily articulated with other buzzwords in the discipline, notably “decolonizing”, “anthropocene” and “ecological destruction”. But when we focus on ontology’s applications in anthropology there is already more uniformity. One common point of ontology in its anthropological garb is a heavy emphasis on “radical alterity” – the plea for an anthropologist’s profound immersion in the otherness of the society studied in order to come loose of the perspectives of the own society. This article focuses on this special version of ontology. But also in this restricted context my focus is more modest. Rather than questioning ontology and its possible contribution to anthropology theoretically (we have already many and highly sophisticated debates on the notion’s theoretical merits2), – I propose to focus on the performance of the notion, its promises and problems, in ethnographic settings. A leading question will be the usefulness of the emphasis on radical alterity. Is this the concept anthropology needs to face present-day global challenges? And does it really help to overcome binary oppositions that so long have haunted our discipline? A related question is about the quite curious regional spread of the notion in our discipline. Ontology seems to thrive in the anthropology of Amazonia, Melanesia and Mongolia, but much less in the anthropology of Africa. To what extent can this remarkable regional spread help to understand the notion’s vicissitudes in anthropological practice?

Of course, developments within the discipline have to be placed in a broader context. In retrospect anthropology’s obsession with purity during a major part of the 20th century – with untouched, authentic cultures – fitted in with a curious mixture of an effort to overcome racism with the practical demands of colonial “indirect government.” But what about the more recent return to purity? In her classical study Purity and Danger3 Mary Douglas focuses on the crucial role of dirt and pollution in people’s effort for ordering their society. What then is the dirt that inspires the present-day return of purity in anthropology? At first sight this return may surprise in a world that highlights increasingly the basic impurity of everyday life. Especially Mary Douglas’ somewhat surprising conclusions about purity might still be of interest here.

The anthropologist in front of “his” house, Bagbeze (Cameroon), 1971.

I insisted on living in this “poto-poto” house because I wanted a traditional place to stay, only to find out later that this type of housing had been introduced a few decades earlier under colonial rule.

An historian entering anthropology

My remembrances of 60 years back may be interesting to highlight the changeability of anthropology’s relation to history that were later to frame the emergence of ontology as a solution to anthropology’s growing uncertainties. As said, my starting years as an historian in anthropology’s land were quite disorienting. One of the first things my anthropology professor asked me to do was to make an excerpt of Lévi-Strauss’ opening article of his Anthropologie structurale4, then still only available in French. The article was called Anthropologie et histoire, but I struggled in vain to discover something in it I would call history. Later on, I read Claude Lévi-Strauss’ poetic but sad song Tristes tropiques5 about all the cultural riches that was getting lost in the tropics. And I understood that the idea of a lost purity does not fit in well with history as an ongoing process. Many of the classic monographs I had to study (Evans-Pritchard’s The Nuer or Raymond Firth’s We The Tikopia6) were written in “the ethnographic present” – that is, the present tense of the book referred to the “pre-contact situation”, just prior to colonial rule, and thus also prior of what the ethnographer had witnessed. For an historian some sort of splits position.

A more serious problem was, that – when in 1971 I finally started my first long-term field-work among the Maka (in the forest area of southeast Cameroon) I was confronted by classic anthropological topics like kinship and witchcraft, but in quite a different way I had expected. My exams in kinship on systems of circulating connubium and other forms of “kinship algebra” were of little help for understanding the startling ways – startling for me at least – in which Maka villagers “worked” with kinship terms, “discovering” relatives in new settings (for instance in the cities) or the logics of segmentary lineage systems, the core terms allowing for different interpretations and often surprising equations.7 “Witchcraft” was for them not a “traditional structure” but rather a loose assemblage of notions allowing shifting interpretations of especially new developments.

My disappointment with what classical anthropology could offer for me in the field was, however, mitigated by a fresh wind blowing through the discipline since the end of the 1960s – the so-called “crisis” in anthropology mentioned before. The move of anthropologists into what was then called “complex societies”8 – field-work in Latin America, Asia and even Europe – made ideas of the primitive isolate, or an ethnographic present impossible to maintain. In these new settings anthropologists could no longer avoid history. A seminal reflection on anthropologists’ problems in dealing with time was Johannes Fabian’s Time and the Other9 because it showed the problematic consequences of the neglect of history also for the older regions where anthropological field-work started (like Oceania or Africa). The tendency to see people studied as our “contemporary ancestors” meant placing them outside history (cf. the practice signaled earlier to discuss “social change” in the last chapter of anthropological monographs, as some sort of an appendix). Striking is that the reorientation came from reflections over field-work – since Malinowski the discipline’s arcanum. The “writing culture” turn – originating in the US, but inspired by “French theory” and also carried by reactions from the South – challenged anthropologists to reflect about what they were doing when they claimed to be describing “a culture.” James Clifford10 criticized the “substantialist” idea of culture, advocating rather a view on culture as constantly “emergent” and the product of constant processes of hybridization; hence his plea for a “Caribbean notion of culture.”11 Arjun Appadurai12 advised anthropology even to drop the notion of culture all together – a kind of sacrilege in view of the notion’s central place in especially American anthropology. Appadurai, like Fabian before him, warned that current notions of culture fed into closed and exclusionary notions of identity. Georges Marcus and Michael Fischer13 convincingly undermined the idea of “a culture” as a given, waiting to be revealed by the anthropologist, just like the archaeologist excavates an object. In their view an ethnography of another culture should rather be seen as the product of a dialogue between researchers and local interlocutors. I particularly loved the opening chapter of James Clifford’s book14, “The pure products go crazy”, in which representatives of “another culture” do not at all behave as they should in the anthropological view, but instead seemed to enjoy all sorts of “weird” playing with new elements.15 Confer also Clifford’s example from Lévi-Strauss’s “ethnography” of 1941 New York, featuring “a feathered Indian” in a beaded jacket but also with a Parker pen sitting close to him in the American room of the New York Public Library where the anthropologist was struggling with his Les Structures élémentaires de la parenté16 that was to lay the foundations of his Anthropologie structurale17. For Lévi-Strauss the Indian (with a pen!) “brought him back in time” but was also a “discomforting” presence. For Clifford he is another scholar, offering a glimpse of another future18.

It might be important to emphasize the wider relevance of these debates about “writing culture.” Clearly these anthropologists were worried about the success of anthropology’s notion of culture outside academia. In the 1930s Ruth Benedict gave a most poetic expression to this notion – in good Boasian style – quoting a native American chief:

“In the beginning God gave to every people a cup, a cup of clay, and from this they drank their life…. They all dipped it in the water…. But their cups were different. Our cup is broken now. It has passed away.”19

Progressive as this notion may have been at the time – emphasizing the value and coherence of other cultures, to be seen as different but certainly not as inferior20 – subsequently anthropologists began to realize that they might have been too successful in spreading it.21 From the 1980s on it became increasingly clear that the concept could be easily hijacked by right-wing groups in struggles over exclusion and belonging. The warnings by Clifford, Marcus and many others from the 1980s on against worrying implications of a substantialist culture concept and its role in maintaining boundaries – each society marked by its own cohesive “culture” – were inspired by this wider context, just like their plea for a more open concept that could help to focus on creative moments of hybridization.

For me this is what history is about: continuous change, unexpected combinations setting in motion unpredictable processes. It was particularly James Clifford’s plea for a “hybrid” notion of culture that was an eye opener: the hybrid not as a sad remainder of an earlier pure form, but as the sign of creativity, producing new and constantly emergent forms. Indeed doesn’t Michel Foucault’s genealogical approach not teach us that all phenomena have mixed origins: the hybrid not as an anomaly but as normal in the flow of things? Another high point in anthropology’s reorientation was for me therefore Michael Taussig’s 1987 Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man: A study in Terror and Healing22, especially because of this emphasis on the power of “epistemic murk.” With him, coherence, and order are no longer central concerns — on the contrary. When trying to understand why in Colombia descendants of Spanish settlers continue to descend the steep mountain paths from the highlands into the humid Amazonian jungle in the country’s southeast corner to look for healing with local shamans, Taussig focuses on transgression and the healing power of chaos. For him the shamans’ long yagé nights — during which a mix of hallucinatory plants evokes wild visions, while violently opening all the body’s orifices — work like Walter Benjamin’s “technique of montage.” Taussig’s shaman turned out to be a master in conjuring up powerful pintas — pictures — that often reflect colonial traumas: the irrational slaughtering of local labor during the horrors of the wild rubber boom, the splendor of (post-)colonial armies. Healing is only possible through a most physical immersion in terror, and the shaman’s imaginary seems to be shaped by a constant play of reflecting, sending images back to the suffering client. So much for purity: the shaman’s “montages” work because of his talent in bringing together different worlds – or to put it differently, in effacing boundaries.23 This notion of epistemic murk as a source of power poses a basic dilemma for academic research. If a basic task for the academic it to create clarity and transparency, how to deal with the power generated by confusion and montage? Or to put it more concretely for a topic that came to haunt me in my own research in Cameroun: how to understand the remarkable resilience of local ideas about “witchcraft” which seem to graft themselves onto modern changes instead of “withering away,” if this ongoing power seems to stem from the unsystematic character of these imaginaries who constitute anything but a system? What to do if attempts to clarify such riddles seem to evacuate precisely what makes these local ideas so powerful?

Ontology: a quest for purity?

No wonder that the sudden emergence of ontology as a new buzzword in anthropology (sudden at least in my experience) came for me as a surprise. It seemed to sit most uneasily with the reorientation in anthropology towards hybrid forms in constant movement that had brought me relief. My first reaction was that it meant a return to the older “substantive” notion of culture we seemed to have overcome, also because of its problematic implications in the present-day world. But is this fair? On closer inspection, this might be too rash a conclusion. I had been confronted with the notion before, but to be frank I used to be quite happy that the notion seemed to be safely tucked away in philosophy. But the very idea of an “ontological turn” risks to cover up the dazzling variety in concept’s use, also in the limited context of anthropology. I admired, for instance, Annemarie Mol’s use of the Latourian version of the notion in her The Body Multiple – Ontology in Medical Practice24 – especially the way she used ethnography to show how in medical practice the ontology of an illness can become multiple; in this sense her title, combining ontology and multiple is programmatic. Yet I became worried when with Latour’s sudden metamorphosis into an anthropologist – and the quite open view of what he and his followers see as “anthropological field-work” – ontology became central in anthropological discussions of field-work and ethnography in general. Mol’s combination of ontology and multiplicity works well in her study “at home.” But what happens when the notion is used to bridge deeper cultural differences as in most anthropology? What happens then with the multiplicity pole?

For Sahlins, the saving grace of ontology for anthropology is, as said, its rigorous focus on “radical alterity” which will help to liberate anthropologists from the frames imposed by their own culture, thus opening up the discipline to alternative perspectives. But it may be questionable whether “radical alterity” is what the discipline needs in a global context that is so deeply marked by processes of hybridization. A related question is about the regional spread of ontology studies. As said, the notion seems to flower – at least in anthropology – in Amazonia, Melanesia and Mongolia, three areas that are widely different, geographically, culturally and in politico-economic respect. One thing they have in common is that even in present-day contexts these regions are still at the very periphery of capitalism; of course, all three are deeply affected by it (be it in different ways) but there still seems to be no “real subsumption of labor to capital” (to borrow Marx’ good old formulation). Yet, the same applies to many parts of Africa where most of my examples come from, and in the anthropology on this continent, ontology – although not completely absent – seems to be less rooted. This might relate to problems of the notion in dealing with history.

These questions – ontology’s relation to multiplicity, the relevance of its focus on radical alterity in present-day contexts, and its relative absence in African studies (as in the Middle East) – will be central below. But as said, I propose to approach them not from theoretical considerations but rather to start from more or less concrete experiences of how the ontology notion works out in practice – in research and ethnography. So, below first some of my surprise encounters with ontology, followed by some more general remarks.

Meke Blaise, my research assistant for more than 40 years, who patiently taught me that custom was not fixed but constantly innovated under changing circumstances. Andjou (Cameroon), 1994.

An African versus a Melanesian Ontology?

In 2001, while I taught for a semester in New York City, Jean Comaroff invited me over to Chicago to give a paper for her Africa seminar. My paper was on the link between “witchcraft” and intimacy – a kind of pre-study for a book that would only appear in 2013 (mills turn slowly in academia). The idea was to explore to what extent the insistence of my Maka friends in the forest of Southeast Cameroon on the djambe le ndjaw (the “witchcraft of the house”) being by far the most dangerous, could help to anchor what people mean when they use terms like “witchcraft.”25 Anthropologists have struggled for long to capture such notions and I hoped that the link with intimacy, apparently recurring in many settings, might help to better outline them. In my talk I tried to develop a broader, comparative perspective, mentioning all sorts of variations and shifts in such linking of “witchcraft” to intimacy. So, I referred also to the idea of some authors on Melanesia that there “witches” were often outsiders from other villages. I added that, however, in many cases they turned out to work through allies inside – the link with intimacy coming in through the backdoor. The discussion was opened by an elderly gentleman at the back whom I could not see very well. His question was brief but direct: “so you were talking about a contrast between an African and a Melanesian ontology?” The question hit me like a brick. My aim had been to emphasize the dynamics of what people call “witchcraft” and the enormous flexibility these so-called traditional ideas exhibited, grafting themselves on modern changes that were supposed to bring a disenchantment. All that seemed to me very difficult to capture by a notion like “an African ontology.” So I felt completely misunderstood and I am afraid my response was fairly brief. However, Jean Comaroff, before opening the floor for another question, thanked “Marshall” for his question. Only then I understood that the first questioner had been Marshall Sahlins and that I had had good reason to take the question more seriously. Indeed, in the following years I would stumble on the ontology notion with increasing regularity.

My acute discomfort at the ontology notion coming up so abruptly at this occasion had to do with the quite haphazard way I had landed with the concept of “witchcraft” altogether. This came out of my Ph.D. research among the Maka in the forest region of Cameroon which had a rocky course. When I arrived there in 1971 my plan was to study politics and certainly not witchcraft. In those days, even anthropology was infected by the modernization bug, so my aim was to avoid what I saw as the “traditional” hobby horses of classical anthropology – kinship, but also witchcraft. I wanted to be a “modern” anthropologist and therefore I opted for the idea, novel at the time, of “local level politics” I hoped to study local politics in interaction with (post-)colonial state formation, emergence of new elites, and nation-building. But my first experiences were quite disheartening: I soon learned that the new authorities (Cameroon had become independent in 1960) were not waiting for a white anthropologist studying national politics, so I soon was on the blacklist of the secret service and elites were avoiding me as much as they could. Village politics seemed to be less sensitive, so I decided to start on that level. But once I had settled in a village I discovered that whenever I wanted to discuss politics, my interlocutors started to refer to the djambe – a Maka term they translated by sorcellerie (witchcraft). Moreover, they made me understand that it was in the nocturnal world of the djambe that the real confrontations were taking place, deciding what happened in the world of the day. So my research was drawn ever deep in the witchcraft vortex.

Moreover, it was again this djambe that allowed me to make the link between the local and the national on which I had wanted to focus from the start. Of course, I had never given up the idea of local level politics, and by just being there I managed to get a view from below on what the state meant for the villagers. However, my problem remained for quite some time that there seemed to be a basic chasm between the local level and the higher layers of the political organization. In the highly authoritarian one-party state set up by Ahmadou Ahidjo, Cameroon’s first President (1960-1982), things seemed to be organized only top-down. The keyword was unité – everything had to be done to confirm the unity of the population behind the president – which necessitated a constant vigilance against threatening subversion.26 Politicians were constantly reminded that they owed their nomination for lucrative positions (mayor, parliamentarian, minister, also party positions at the regional or national level) only to the goodwill of the party-top and definitely NOT to their local support. On the contrary, any attempt to build up a local support base, was soon seen as a form of subversion of the unité nationale – a very serious accusation that made many overly ambitious elites end up in Tcholliré, a horrible concentration camp in the North of the country. All this created a configuration in which the state seemed to hang above the local level as some sort of luminary condensation of power – a huge spacecraft – without any influence from below. However, it was precisely the register of occult power (djambe) that helped to break through this official view of an all-powerful state elite and an obedient population whose only role seemed to show adhésion and vigilance. Indeed, it was this resilient capacity of the djambe notions, grafting themselves on modern changes and able to bridge the distance between the village and the new levels of the state that made it so crucial for understanding what politics meant in practice – at the higher levels as much as in the local setting.

I tried to grasp these impressive and quite frightening dynamics of “witchcraft” – then still generally seen as a traditional remainder that was to wither away with “modernization” – in the title of my first book, The Modernity of Witchcraft27. Misleading as the title may have been (some read it as an eulogy of these dark forces, others think it implies that witchcraft is only about modernity – who would ever suggest this?) it did express my own bafflement at the omnipresence of modern technology as central to the djambe imaginary – nganga (healers) claiming to have destroyed a “nocturnal airstrip” in the village so that witches could not land their planes anymore; also the use of medical language, the central role of money and many other new elements. So, for me it became vital to highlight the changeability and inconsistency of witchcraft imaginaries as the secret of their resilience in the face of deep changes. Other recent authors developed similar views, emphasizing the need to historicize witchcraft – not as a given set of ideas but as a hybrid, incorporating constantly new elements. Anthropologist Joseph Tonda (University of Libreville) concluded from his kaleidoscopic overview of a constant creating new forms of healing in Gabon and Congo-Brazzaville, mixing local, Christian and other elements, that the witchcraft of the post-colony is a colonial product, completely remade by a constantly changing context.

Danish anthropologist Nils Bubandt used his material on gua in East Indonesia to put into doubt Evans-Pritchard’s idea – fundamental to classical anthropology – of Zande magic and witchcraft as an “explanatory system.” For Bubandt gua is about “aporia” – basic doubt –, inspiring desperate efforts to overcome confrontations with the “uncanny”. Bubandt characterizes the recent history of the area (East Halmaheira) as marked by people’s desperate hope that external interventions will put an end to this evil – but of course every time again in vain. Florence Bernault shows in her Colonial Transactions28 for Gabon how the convergence (rather than the opposition) between colonial and local ideas about spirits produce new hybrid forms. In a similar vein Andrea Ceriana Mayneri29 (2014) follows in detail for the neighboring Central African Republic how quite occasional choices in the translation of local terms (with a French priest and a local interpreter as intermediaries) produce the new forms of “witchcraft” that in recent times have come to haunt the country’s population. Compare also Isak Niehaus moving study30 of how “witchcraft” ideas and accusations change content and direction during the tragic life of his research assistant in the South African Lowveld.

It may be clear for all these issues, acquiring great urgency in these different settings, how inspiring an approach to culture as constantly emergent – hybridization producing new forms – can be, also for fully taking into account the often vivid creativity involved in these processes. It may be equally clear why none of these authors feel inclined to evoke the notion of ontology. Radical differences and static typologies seem to be of little use in a field that is so deeply marked by constant flux and challenging transgression.

Another encounter with ontology: Congo Basin Mobility versus “An Amazonian Package”

Much more recently another confrontation with ontology thinking produced a similar “aporia” for me. This time the topic was completely different but certain implications of the concept made it similarly difficult for me to work with it. In 2020, Cameroonian historian turned philosopher, Achille Mbembe, asked me to participate in his ambitious REGION2050 project (subtitled “Moving spaces, porous borders and pathways of regionalization”), in particular in its subprogramme on the Congo basin.31 Mbembe’s idea was that this subprogramme could make a seminal contribution to the overall project by exploring alternative forms of border-making – that is, alternative to the notion of border as generalized by nation state projects all over the present-day world. Special aspects of the Congo-Basin, seem to make boundary maintenance a precarious undertaking: its dense forest and shifting waterways, but also the extreme mobility of its societies and their open character make for constantly moving boundaries. An additional issue to explore was how local ways of creating and maintaining delimitations articulated over the last century with formal borders imposed by colonization and subsequent nation-building. Especially the last aspect related quite well to my own work on Cameroon, and since the Maka area is at the very limits of the hugely ramifying network of the Congo waterways, I gladly accepted to join the project. After a year of discussions (unfortunately on zoom because of the lockdown) Mbembe – apparently hoping for more theoretical sophistication in our group – asked us to read and discuss a recent article “Moral Sources and the Reproduction of the Amazonian Package” by Carlos Londono Sulkin32. The article turned out to analyze variations among Amazonian societies which in Londono Sulkin’s view should be studied as fitting into one common frame, an “Amazonian package,” that he presented as specific to the zone and radically different to societies elsewhere. As I foresaw, this brought another confrontation with ontology thinking, in the meantime having become highly fashionable in anthropology in general.

Mbembe was certainly right that Londono Sulkin’s article, elegantly written and analyzing a wealth of ethnographic data, was pervaded by theoretical thinking of great depth. Moreover, the comparison Congo – Amazonia was most promising. Their huge river basins have many similarities: dense forest, alternated by some clearings; huge waterways that are, moreover, navigable for considerable stretches; and in more recent times, similar problems of destructive exploitation and deforestation. All the more striking that the dominant discourse in the academic literature about these two regions is so different. For Amazonian studies the Lévi-Straussian heritage brought a consistent focus on the otherness of Amazonian societies – compare, for instance, Pierre Clastres’ heavy emphasis33 on these societies being radically “against the state.” More recently, this otherness was powerfully theorized by Eduardo Viveiros de Castro34 (1998, 2012) who made the region one of the biotopes of ontology in anthropology. De Castro later picked up Lévi-Strauss’ fascination with the nature-culture divide to develop his notion of “perspectivism,” adding impressive theoretical sophistication of his own through borrowings from Leibnitz, Nietzsche, Deleuze and others. For Viveiros de Castro, Amazonian societies organize themselves according to a radically different “multi-naturalist” ontology (humans, animals and other natural objects being different corporeal states of one condition) that is the opposite of western “multi-culturalism” (the current view in Western academia that a supposedly universal nature is interpreted by people from different cultural points of view). Londono Sulkin most interestingly condensed all this in his idea of an “Amazonian package” allowing for some internal difference but basically the same for the whole region. Typical is his synchronic approach in trying to grasp the variations and the coherence of this “package.” Challenged by one of his commentators (the article was published in Current Anthropology and therefore followed by a rich series of comments) to take into account how this package was historically affected by more hierarchical societies that surrounded the region from all sides (also in pre-Columbian times), Londono Sulkin’s typical reply was that this had to be a topic for another study35. Of course, such a limitation is justified in a context of an article. Yet, his reply raises questions about the (im)possibility of separating a topic from its history.

In contrast, academic studies of the Congo basin were and are deeply marked by the epic story of the Bantu migration from the present Cameroon-Nigeria border through (and alongside) the forest to populate most of the continent below the Douala – Mombasa line. Hence a consistent emphasis on the historicity of this millennia-long process and the internal differentiation this produced. The towering academic figure in this field is historian Jan Vansina with his lifelong insistence that these forest societies – for many still associated with Conrad’s “heart of darkness” – were not outside history, and that it is possible, against all appearances and despite the scarcity of written sources, to retrieve their history. Especially in his 1990 magnum opus – Paths in the Rainforests: Towards a History of Political Tradition in Equatorial Africa36 – Vansina managed to follow the increasing complexity of social organization over time, allowing also for more hierarchical configurations emerging in some societies. This implied also consistent attention to trade and exchange.

An interesting question is of course why such different academic visions developed concerning societies that have so many characteristics in common. Of course, intellectual genealogy plays an important role here. It is hard to imagine inspiring figures that could be more different than Claude Lévi-Strauss and Jan Vansina. But, as indicated already above, particular historical circumstances play a role as well. For Equatorial Africa it is almost impossible to avoid a more historical approach since the surprising linguistic unity over a huge zone (roughly from Douala to Durban) clearly resulted from this epic “Bantu migration” as a millennial process.37 A similar longue durée story seems to be lacking for Amazonia. Or must it still be unearthed? In any case, for our questions about different ways of border-making in the Congo basin and wider in Africa – frontiers as porous and constantly shifting – a historical approach, emphasizing change and emergence, seemed to be more promising. Again, ontology, also in its Amazonian garb, seemed to fit badly with the questions raised by our field.38

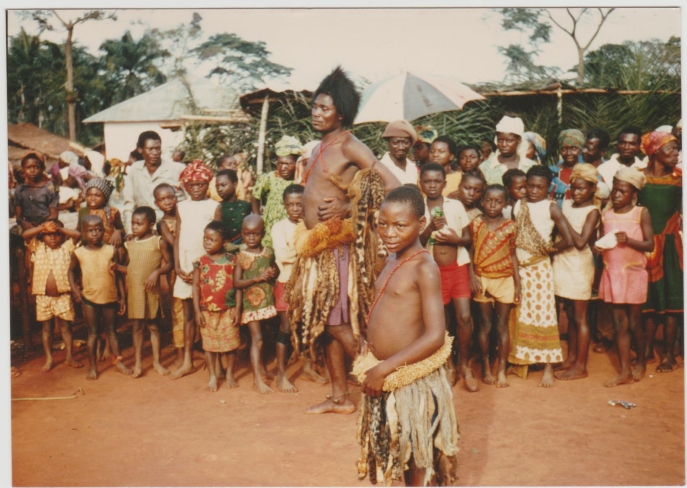

In the 1970s Mezing Merlin was the most powerful nganga (healer) on our road. He danced from sunset to dawn calling up the spirits to heal his clients. The young girl in front was his pupil; Merlin had to teach her how to control the djambe (witchcraft) in her belly so that she could become a powerful nganga in her turn. Mpoundou (Cameroon), 1971.

Ontology: A Return of Culture?

High time to have a more general look at the concept and the way it was launched in anthropology. In their programmatic essay “The Politics of Ontology: Anthropological Positions”, Martin Holbraad, Morton Pedersen and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro (2014)39 first signal that ontology as a term evokes essence, but then proceed by distinguishing three versions: ontology as a “traditional concept of philosophy” (apparently dominated by this essentialist tenor), then “the sociological critique of it” and finally “the anthropological concept of ontology.” This anthropological version seems to have a quite peculiar relation to the notion’s essentialist core since it rather aims to highlight “the power of difference.” We are back here with the focus on “radical alterity.” Apparently, the idea is that by obliging anthropologists to fully accept the radical otherness of the people studied the research will bring out the power of difference, not only with the parameters of the anthropologist’s own society but also internally in the societies studied. This seems to be quite a big jump, from the essentialist implications of the philosophical starting point to attention on how people live with difference. Moreover, while ontology’s capacity to highlight differences between societies (notably between the one studied and the own society) is quite apparent, it is less clear how ontology can help to focus on differences inside these societies. Another problem is that it is hard to understand how in our discipline a focus on radical alterity can avoid falling back on the old anthropological fascination with the purity of “untouched” cultures and societies – in their “pre-contact” stage.

In 2008, only five years after Viveiros de Castro introduced ontology in his keynote at the annual conference of the British association of anthropology as the solution to anthropology’s crisis, the “Manchester group for debates in anthropological theory” discussed a motion with the telling title “Ontology is just another word for culture.”40 In this debating group, participants vote on a motion after it is thoroughly discussed. This time the outcome of the vote was in favor of the motion; indeed, the very wording of the motion suggested already a certain disappointment in what the ontology concept could do for anthropology. Despite my discomfort with the notion, highlighted above, I would have hesitated to vote in favor of the motion. Ontology is much more than “just culture,” if only because it seems to mean different things to different people (à chacun son ontologie…). Yet, the Manchester debate did point out interesting convergences with what James Clifford used to call an “essentialist notion of culture,” notably by the emphasis on “radical alterity.” For Clifford it was this vision of each society having its own coherent culture, marked by a specific way of being, that had made classical anthropology so ill-prepared for dealing with all the upheavals of colonialism and the transition after 1960 to post-coloniality. The end of the cold war around 1990 may have been even more important in bringing out the dangers of such a notion of culture. The “new world order,” at the time announced by George Bush senior and his organic intellectual Francis Fukuyama, turned out to be less about global flows than about cultural wars and vicious conflicts over belonging and exclusion.41 In such a context the classical anthropological culture concept with its implications of radical difference can, indeed, become very dangerous. The question whether the ontological turn risks to bring back this idea is therefore relevant, particularly now. Can we use the ontology concept in anthropology without fixing cultural differences? Can the concept deal with a reality of constant hybridization, vehemently denied by protagonists of “tradition,” but all the more real in producing new forms of exclusion?

Apparently, it is not impossible. Compare, for instance, Morton Pedersen’s vibrant monograph Not Quite Shamans42 on people’s uncertainties about their shamans in post-socialist Mongolia. After 2010 Pedersen became one of the most eloquent prophets of the ontological turn in anthropology. Yet in this book his ethnography is full of unexpected turns and creativity, his style of ontology certainly not becoming a straightjacket for a reality marked by differences and tensions. But one can ask what the ontology notion did for his field-work and ethnography. It certainly inspired him to interesting theoretical explorations but his fieldwork comes across as that of a sensitive anthropologist, not necessarily as ontological. More recently also Anna Tsing, with her well-known genius for fusion (as a necessary counterpart to friction), explored how ontology and multiplicity can be combined in practice.43 She is inspired in this by Annemarie Mol’s The Body Multiple44, already quoted, because of the later’s success in using ontology precisely to highlight multiplicity. But Tsing adds a caveat. She wonders whether Mol’s way of combining the two worked so well because her ethnography is set in her own society. When an anthropologist has to cross cultural difference, ordering ambiguous and fuzzy ethnographic data into an orderly ontology may require already such an effort that multiplicity will suffer. Again, the test is whether an ontological approach can deal with mobility and friction as an ongoing process. In her 2005 book, Tsing’s own mantra “friction is productive” helped her to grasp in seminal ways processes of hybridization creating unexpected linkages and outcomes in struggles over the exploitation of the Kalimantan forest.45 Can ontology similarly help to understand multiplicity and friction without evoking an image of opposing blocks? Does it help to highlight how the elements involved in a mutual articulation are constantly shape-shifting because of this mutual articulation?

In his 2013 introduction to Descola’s Beyond Nature and Culture46 quoted at the beginning of this article, Marshall Sahlins sees ontology as the way to get rid of current binary oppositions that hinder it to get loose of its Western moorings. The problem is, however, that in practice the ontology notion seems to inspire its own binary oppositions – stemming from the focus on a radical alterity which encourages to oppose social formations as, indeed, radically different. What to think, for instance of the binaries inspired by Viveiros de Castro’s “perspectivism.” In his brillant Métaphysiques cannibales47 he sketches an “Amazonian ontology” that is in every respect the opposite of “the academic view”; a common métaphysique de la prédation seems to mark all Amazonian societies; and can be compared to “Melanesian ontologies.” The academic view is their opposite because it is “commodity-based” and has therefore great difficulty in understanding “gift-based societies” like the Amazonians or the Melanesians.48 There are parallels here to the way Marylin Strathern opposes Melanesian “dividualism” to Western individualism, again the one as the opposite of the other.49 Of course the great theoretical sophistication of both authors makes them soar above a simplistic reading of such contrasts. Yet, there might be good reason to underline possible dangers of such binary oppositions in a global context where they seem to take on a life of their own in violent conflicts about belonging and authentication.

The same applies to what for me is the main danger of the ontological turn in anthropology: its apparent unease with history which seems to be once more relegated to the margins. Again, a return to classical anthropology and the way it dealt with “social change”? After all, the discipline’s turn to history (roughly since the last quarter of the last century) turned out to be the most effective antidote to anthropology’s bent for celebrating the purity of an authentic otherness.50 Its unease with history might also be one of the reasons why ontology had limited success in African studies. Remember the difficulties we had in our Congo basin project in applying the idea of a coherent “Amazonian package” in our explorations of special forms of boundary making. The all-overriding role of the millennial Bantu-migration through the Congo forest made it impossible to conjure up such a timeless model as Londono Sulkin did with his “Amazonian package.” The same applies to other parts of Africa. In East Africa, the memory of the long-term migration of cattle-keeping groups towards the South similarly marks the historicity of present-day societies. And, if there is a special ontology for the Sahel societies in Western Africa, it must have been deeply marked by the equally epic and millennial history of the Trans-Sahara trade (in which African initiative was certainly as important as that by outsiders). If the ongoing importance of such historical trajectories is fully recognized, it is impossible to maintain an idea of each society being locked in its own ontological bubble.51 In their 2014 statement quoted before, Holbraad, Pedersen and Viveiros de Castro plead indeed for a more dynamic notion of ontology in anthropology as addressing the question of “how persons and things could alter from themselves” – this should also imply a focus on “differences ... within.”52 The question remains whether the ontology concept with its essentialist implications is not more of a ballast for this than a source of inspiration – certainly if one takes into the account the powerful role of a pure, untouched fata morgana in anthropology.

All this makes it all the more enigmatic why the ontology notion – often in combination with other buzzwords like Anthropocene or decolonial – has become so popular in different branches of anthropology over the last decades, all the more so since this happened in a world that is ever more characterized by hybridization and métissage. It may be clear why the classical notion of culture and its quest for a pure, authentic otherness thrived during the middle part of the last century. For anthropology as a new discipline it was then crucial to emancipate itself from Eurocentric visions of the “primitives” as an earlier stage in an unilineal human evolution. Moreover, the context of indirect rule of those days gave efforts to understand “what made these societies tick” also a practical utility. In such an anthropological vision of a lost purity “contact” gets the allure of some sort of “defilement,” evoking Mary Douglas’ central idea of dirt as “a matter out of place.” But what then is the dirt that now preoccupies ontologists in their return to a quest for purity? The answer will be very complicated but maybe it is precisely the confusing character of late capitalist society in which clear lines seem to get entangled in unexpected forms of hybridization that makes the simplicity of radical alterity once more tempting. But now with the hope that parameters of these other cultures will help to liberate us from the conceptual frames of our own society that have turned out to be so disappointing in providing clarity.

In this respect the somewhat unexpected ending from Mary Douglas’ 1966 Purity and Danger might be enlightening. One of the reasons of the ongoing attraction of the book might be the surprising turns in her argument. The book is, for instance, much less about purity than about dirt “as matter out of place” and therefore central to people’s efforts to create order. Only towards the very end the author focuses on what purity is. I must confess that by that time I expected a celebration of it, as dirt’s antipode, but Douglas swerves again into a different direction:

“The quest for purity is pursued by rejection. If follows that when purity is not a symbol but something lived it must be poor and barren. It is part of our condition that the purity for which we strive and sacrifice so much turns out to be hard and dead as a stone when we get it.”53

For her, this explains why rituals include so often dirt – this matter that seems to be out of place – in the very heart of their performances, as a transgression that is basic to their power. The unexpected outcome of her book is that purity needs dirt – not just as an antipode but as an inherent element – to become livable.

Douglas’ warnings are important if one takes, again, the role of the discipline in wider society into account. It remains, for instance, regrettable that anthropology did not take a clearer stance against the concept of identity – a concept that inevitably raises issues of purity – invading the social sciences since the end of the last century.54 Again, our classical notion of culture – each society with its own culture as a coherent whole – seems to play a key role in setting the identity trap, with its inevitable opposing of belonging and exclusion. Worrying is that even identities which claim to be transgressive – and therefore progressive – end up producing binary oppositions between those who are “in” and who are “out.” The power of identity politics has become such that even “thinking out of the box” seems to require clear boundaries and typologies suggesting radical differences. An additional problem is, moreover, that such binary ways of thinking are often associated with fairly flat ideas of power: one side is seen as having power and the other as powerless.55 Again, history as a critical discipline can work as an antidote, highlighting the relativity of any form of identity, and the ambiguity of power. It remains to be seen how ontology, at least in a version that is preoccupied by radical alterity, can help to get out of the identity trap.

The same applies to ontology’s articulation with other present-day buzzwords in our discipline. Descola’s rediscovery of animism and totemism as answers from other cultures to the western way of opposing nature and culture can certainly help to overcome rigid separations of the human from other forms of life and their implications for ecological destruction.56 But there is a danger of exaggerating the otherness of animism or totemism. In the everyday we are now all over the world confronted with hybrid forms, like self-identifying “traditional priests” for whom the animated character of nature is not a reason to stop allowing it to be exploited in brutal forms.57 Similarly, the search for radical alterity may help to realize how much our conceptual frameworks are marked by the colonial past. But again, focusing on “colonial transactions” – Florence Bernault’s notion for understanding the convergence (rather than the opposition) of colonial and African ideas in Gabon’s history as hybrid forms58 – may help us better to understand the surprising resilience of the colonial. Again, quite urgent in view of the striking colonial overtones of President Trump’s audacious MAGA visions.

Anthropology’s penchant for purity has clear attractions: it promises clarity, both empirically and theoretically, and neat boundaries. Thus, it may appeal also to the present-day need for “safe spaces.” But we live in an unsafe world in which binary oppositions do not really work, where most things are impure and boundaries are shifting and porous, now as in the past. This is why anthropology needs concepts that can deal with hybridity, friction and ambiguity.

Notes

1

Many thanks for inspiring comments and suggestions to (in order of appearance) Birgit Meyer, Kriti Kapila, Andrea Ceriana Mayneri, George Paul Meiu, Jean and John Comaroff, James H. Smith and two anonymous reviewers for passés futurs.

2

See, for instance, Lucas Bessire and David Bond, “Ontological Anthropology and the Deferral of Critique,” American Ethnologist, vol. 41, no. 3, 2014, pp., 440-455.

3

Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger. An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo, London, Routledge 1966.

4

Claude Lévi-Strauss, Anthropologie structurale, Paris, Plon, 1958.

5

Claude Lévi-Strauss, Tristes tropiques, Paris, Plon, 1955.

6

Edward Evan Evans-Pritchard, The Nuer: A Description of the Modes of Livelihood and Political Institutions of a Nilotic People, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1940; Raymond Firth, We The Tikopia: A Sociological Study Of Kinship In Primitive Polynesia, London, Routledge, 1936.

7

It was only in the 1980s and 1990s that first feminist anthropology and then the “new kinship studies” began to study kinship as a flexible order allowing people to “work” with it. In the 1970s anthropologists still tended to study kinship as a fixed system. Cf. Marilyn Strathern, who noted in 1992: “If till now kinship has been a symbol for everything that cannot be changed about social affairs…what will it mean for the way we construe any of our relationships with one another to think of parenting as implementing an option and genetic make-up as an outcome of cultural preference” (Reproducing the Future: Anthropology, Kinship, and the New Reproductive Technologies, London, Routledge, 1992, pp. 34-35). See also Janet Carsten (ed.), Cultures of Relatedness: New Approaches to the Study of Kinship, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2000.

8

“Complex societies” was at the time a current notion, expressing the realization that circumstances in the new areas of field-work (Mexico, Europe) were basically different since the locality of field-work was an intrinsic part of wider whole. Of course, this implied a problematic assumption that this was not the case for earlier localities of field-work (seen as still “primitive” and more or less isolated?).

9

Johannes Fabian, Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object, New York, Columbia University Press, 1983.

10

James Clifford, The Predicament of Culture – Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature and Art, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1988.

11

Cf. also James Clifford and Georges Marcus (eds.), Writing Culture, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1986.

12

Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large – Cultural Dimension of Globalization, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

13

Marcus Georges and Michael Fischer (eds.), Anthropologie as Culture Critique: An Experimental Moment in the Human Sciences, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1986.

14

James Clifford, The Predicament of Culture – Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature and Art, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1988.

15

The title is from a poem by an American dada poet William Carlos Williams (1923).

16

Claude Lévi-Strauss, Les Structures élémentaires de la parenté, Paris, PUF, 1949.

17

Claude Lévi-Strauss, Anthropologie structurale, Paris, Plon, 1958.

18

James Clifford, The Predicament of Culture – Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature and Art, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1988, pp. 237-245.

19

Ruth Benedict, Patterns of Culture, New York, Mentor Books, 1953 [1934], p. 19.

20

Also, more practical motivations played a role here; field-work for many of anthropology’s classical monographs started in the colonial period in a context where the understanding of the local societies as coherent systems promised to be directly relevant for setting up indirect rule.

21

Of course, this anthropological notion of culture was expressed in a dazzling variety of definitions. But recurrent traits were the emphasis on coherence and a neglect of change placing a culture more or less outside time. To be noted, however, that Mary Douglas, for instance, had already in 1966 a mocking comment on “…the anthropologist …. who thinks… of a culture he is studying as a long-established set of values” (Purity and Danger. An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo, London, Routledge, 1966, p. 6). Apparently, her point of departure – dirt as “a matter out of place” and thus obliging people to make rules and order - helped her to escape of the image of culture as frozen in time. In her days it was, within British anthropology, especially the Manchester School around Max Gluckman that developed a growing interest in change. However, Gluckman himself kept referring to “repetitive change” – confirming the social order – as characteristic for African societies (see also Richard Werbner, Anthropology after Gluckman – The Manchester School, Colonial and Postcolonial Transformations, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2020).

22

Michael Taussig, Shamanism, Colonialism, and the Wild Man: A study in Terror and Healing, Chicago, Chicago University Press, 1987.

23

Cf. also the work of Jean and John Comaroff, especially Of Revelation and Revolution I and II, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1991 and 1997. For a different way of effacing boundaries, especially inspiring for my own work. See also Birgit Meyer’s recent explorations around the notion of “interstice” and “in-between” (“In-between: Studying Lived Plurality from the Interstice,” Material Religion, vol. 20, no. 5, 2024, pp. 398-401. https://doi.org/10.1080/17432200.2024.2425195).

24

Annemarie Mol, The Body Multiple: Ontology in Medical Practice, Durham, Duke University Press, 2002.

25

Of course, I had duly started my talk by sketching my embarrassment about the term “witchcraft” as a European term with serious distorting implications when used as a translation of African notions. However, since all over Africa people appropriated the term, also in public debates, we (my Cameroonian colleague, Cyprian Fisiy with whom I began publishing on the topic and I) decided to retain the term – see Peter Geschiere, The Modernity of Witchcraft: Politics and the Occult in Postcolonial Africa, Charlottesville, University of Virginia Press, 1997.

26

Historically, President Ahidjo’s obsession with unity can be seen in relation to his ongoing struggle with Cameroon’s first national movement, the UPC (Union des Peuples du Cameroun) and its charismatic leader, Um Nyobe. In the 1950’s the French – shocked by Um Nyobe ‘s demand for immediate independence – forced the UPC to go underground. Heavily supporting Ahidjo, as representative of a more “cooperative elite,” the French eventually ceded independence to him (1960), but it was only in 1970 and due to heavy military support by the French that Ahidjo succeeded in putting a definitive end to the UPC guerilla in the West of the country.

27

Peter Geschiere, The Modernity of Witchcraft: Politics and the Occult in Postcolonial Africa, Charlottesville, University of Virginia Press, 1997.

28

Florence Bernault, Colonial Transformations – Imaginaries, Bodies and Histories in Gabon, Durham, Duke University Press, 2019.

29

Andrea Ceriana Mayneri, Sorcellerie et prophétisme en Centrafrique: L’imaginaire de la dépossession en pays banda, Paris, Karthala, 2014.

30

Isak Niehaus, Witchcraft and a Life in the New South Africa, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press with the International African Institute, 2013.

31

The REGIONS 2050 project was financed by a collaboration between WISER (University of Witwatersrand) and the German Gerda Henkel Stiftung.

32

Carlos David Londono Sulkin, “Moral Sources and the Reproduction of the Amazonian Package,” Current Anthropology, vol. 58, no. 4, 2017, pp. 477-501.

33

Pierre Clastres, La Société contre l’État – recherches d’anthropologie politique, Paris, Minuit, 1974.

34

Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “Cosmological deixis and Amerindian perspectivism,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, vol. 4, no. 3, 1998, pp. 469-448. Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “Cosmological perspectivism in Amazonia and elsewhere,” HAU: Masterclass Series, no. 1, 2012, pp. 45-168.

35

Carlos David Londono Sulkin, “Moral Sources and the Reproduction of the Amazonian Package,” Current Anthropology, vol. 58, no. 4, 2017, p. 498.

36

Jan Vansina, Paths in the Rainforests: Towards a History of Political Tradition in Equatorial Africa, Madison, University of Wisconsin Press, 1990.

37

However, this does not exclude that also in Equatorial Africa some anthropologists opted for a more structuralist or even a-historical approach. Yet, especially since the 1960s the impact of African historians was particularly strong encouraging increasing interest in the dynamics of African societies in articulation with colonial interventions. Of course, this relates to the wider setting of African independence and forceful efforts (at least intellectually) towards nation-building in the following decades. Historians had a vital role to play in such constructions of nations with their own history.

38

Another striking difference is the minimal role of the Amazonian voice in debates about “perspectivism” and parallel views. Cf. again Carlos David Londono Sulkin, “Moral Sources and the Reproduction of the Amazonian Package,” Current Anthropology, vol. 58, no. 4, 2017, pp. 477-501: none of the seven commentators on this article in Current Anthropology seem to come from the region itself (even more surprising in view of the fact that Jesuits started forcing at least some people from these groups to follow school already in the 17th century); in the African context such an absence of the African voice has become unacceptable. According to some Brazilian colleagues this absence in Amazonian studies reflects the extremely weak political position of “indigenous peoples” in the wider Brazilian context. The Amazonian discussions show also what the consequences are of such absence can be – for instance by the ease with which binary oppositions are used. What to think, for instance, of Viveiros de Castro easy opposition of the “native view” and the “academic view”? It is hard to imagine him getting away with such oppositions in an African context (or for that matter with expressions like “une métaphysique de la prédation” to characterize the native view). In my research on witchcraft and homophobia in Cameroon, many of my informants are both native and academic.

39

Martin Holbraad, Morten Axel Pedersen and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro. “The Politics of Ontology: Anthropological Positions,” Theorizing the Contemporary. Fieldsights, January 2014, https://culanth.org/fieldsights/the-politics-of-ontology-anthropological-positions. See also, Martin Holbraad and Morten Axel Pedersen, The Ontological Turn: An Anthropological Exposition, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2017.

40

Michael Carrithers et al., “Ontology Is Just Another Word for Culture: Motion Tabled at the 2008 Meeting of the Group for Debates in Anthropological Theory, University of Manchester,” Critique of Anthropology, vol. 30, no. 2, 2010, pp. 152-200.

41

Peter Geschiere, Perils of Belonging – Autochthony, Citizenship and Exclusion in Africa and Europe, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2009.

42

Morten Axel Pedersen, Not Quite Shamans—Spirit Worlds and Political Lives in Northern Mongolia, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 2011.

43

Anna Tsing, “A Multispecies Ontological Turn?” in Keiichi Omura et al. (eds.), The World Multiple - Quotidian Politics of Knowing and Generating Entangled Worlds, London, Routledge, 2019, pp. 233-247.

44

Annemarie Mol, The Body Multiple: Ontology in Medical Practice, Durham, Duke University Press, 2002.

45

Anna Tsing, Friction - An Ethnography of Global Connection, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2005.

46

Marshall Sahlins, “Foreword,” in Philippe Descola, Beyond Nature and Culture, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2013, pp. xi-xiv.

47

Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, Métaphysiques cannibales : Lignes d’anthropologie structurale, Paris, PUF, 2009.

48

Such binaries seem to lead Viveiros de Castro far away from Deleuze’s plea for ontology as multiple, contingent and never ending.

49

Of course, Strathern regularly added that she was conscious of internal variation but just needed to make the contrast for the coherence of her theoretical argument. But isn’t this playing with fire? Many people take such contrasts for granted.

50

Striking, for instance, is that in his earlier work Viveiros de Casto was interested in the historicity of Amazonian societies, also in pre-Columbus times (“Images of Nature and Society in Amazonian Study,” Annual Review of Anthropology, no. 25, 1996, pp. 179-200.). But this seems to have disappeared in his later work around the theme of ontology.

51

Another reason for ontology’s lukewarm reception in African studies might be the long battle with ethnicity, energetically imposed by colonials (authorities and missionaries) and further appropriated in post-colonial politics. Thanks to Andrea Ceriana Mayneri for alerting me to ethnicity’s impact also in this context.

52

Martin Holbraad, Morten Axel Pedersen and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro. “The Politics of Ontology: Anthropological Positions,” Theorizing the Contemporary. Fieldsights, January 2014, https://culanth.org/fieldsights/the-politics-of-ontology-anthropological-positions

53

Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger. An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo, London, Routledge, 1966.

54

But see for early warnings Jean-François Bayart, L’Illusion identitaire (Paris, Fayard, 1996), and Seteney Shami, “Circassian Encounters: The Self and the Other and the Production of the Homeland in the North Caucasus,” in Brigit Meyer and Peter Geschiere (eds.), Globalization and Identity – Dialectics of Flow and Closure (London, Blackwell, 1999, pp. 17-47). See also, albeit much later, Peter Geschiere, Perils of Belonging – Autochthony, Citizenship and Exclusion in Africa and Europe (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2009), on belonging. Up till the 1980s “identity” was a concept associated with (social) psychology. See also Michel Agier, La condition cosmopolite – L’anthropologie à l’épreuve du piège identitaire (Paris, La Découverte, 2013); Michel Agier, Borderlands: Towards an Anthropology of the Cosmopolitan Condition (London, Polity Press, 2016); and Jean-Loup Amselle, Branchements. Anthropologie de l’universalité des cultures (Paris, Flammarion. 2001).

55

I am often surprised by colleagues who characterize the relation between anthropologists and “their” people as a one-side power relation. Have they forgotten how utterly dependent they were during their field-work – certainly if it took place in a post-colonial context - on the goodwill of the people with whom they chose to live? A more sophisticated view of power requires to see the relation as marked by a constant balancing of power, shifting over the different phases of the research.

56

Philippe Descola, Beyond Nature and Culture, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2013.

57

Cf. Joseph Tonda’s warning that the sorcellerie which continues to mark everyday life in Gabon and elsewhere in Africa is a product of the colonial period rather than a “traditional” counterpoint (Joseph Tonda, Le Souverain moderne, Paris, Karthala, 2005).

58

Florence Bernault, Colonial Transformations – Imaginaries, Bodies and Histories in Gabon, Durham, Duke University Press, 2019.

Bibliographie

Michel Agier, La Condition cosmopolite. L’anthropologie à l’épreuve du piège identitaire, Paris, La Découverte. 2013.

Michel Agier, Borderlands: Towards an Anthropology of the Cosmopolitan Condition, London, Polity Press, 2016.

Jean-Loup Amselle, Branchements. Anthropologie de l’universalité des cultures, Paris, Flammarion, 2001.

Arjun Appadurai, Modernity at Large – Cultural Dimension of Globalization, Minneapolis, University of Minnesota Press, 1996.

Jean-François Bayart, L’Illusion identitaire, Paris, Fayard, 1996.

Florence Bernault, Colonial Transformations. Imaginaries, Bodies and Histories in Gabon, Durham, Duke University Press, 2019.

Lucas Bessire and David Bond, “Ontological Anthropology and the Deferral of Critique,” American Ethnologist, vol. 41, no. 3, 2014, pp. 440-455.

Nils Bubandt, The Empty Seashell: Witchcraft and Doubt on an Indonesian Island, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 2014.

Michael Carrithers et al., “Ontology Is Just Another Word for Culture: Motion Tabled at the 2008 Meeting of the Group for Debates in Anthropological Theory, University of Manchester,” Critique of Anthropology, vol. 30, no. 2, 2010, p. 152-200.

Janet Carsten (ed.), Cultures of Relatedness: New Approaches to the Study of Kinship, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Andrea Ceriana Mayneri, Sorcellerie et prophétisme en Centrafrique : L’imaginaire de la dépossession en pays banda, Paris, Karthala, 2014.

Pierre Clastres, La Société contre l’État – recherches d’anthropologie politique, Paris, Minuit, 1974.

James Clifford, The Predicament of Culture – Twentieth-Century Ethnography, Literature and Art, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 1988.

James Clifford and Georges Marcus (eds.), Writing Culture, Berkeley, University of California Press, 1986.

Jean and John Comaroff, Of Revelation and Revolution I and II, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1991 and 1997.

Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger. An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo, London, Routledge, 1966.

Edward Evan Evans-Pritchard, Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic among the Azande, Oxford, Clarendon Press, 1937.

Edward Evan Evans-Pritchard, Anthropology and History, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 1961.

Johannes Fabian, Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object, New York, Columbia University Press, 1983.

Francis Fukuyama, The End of History and the Last Man, New York, Free Press, 1992.

Peter Geschiere, The Modernity of Witchcraft: Politics and the Occult in Postcolonial Africa, Charlottesville, University of Virginia Press, 1997.

Peter Geschiere, Perils of Belonging – Autochthony, Citizenship and Exclusion in Africa and Europe, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Peter Geschiere, Witchcraft, Intimacy and Trust—Africa in Comparison, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Martin Holbraad and Morten Axel Pedersen, The Ontological Turn: An Anthropological Exposition, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2017.

Martin Holbraad, Morten Axel Pedersen and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “The Politics of Ontology: Anthropological Positions,” Theorizing the Contemporary. Fieldsights, January 2014, Society for Culture Anthropology. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/the-politics-of-ontology-anthropological-positions

Claude Lévi-Strauss, Tristes tropiques, Paris, Plon, 1955.

Claude Lévi-Strauss, Anthropologie structurale, Paris, Plon, 1958.

Claude Lévi-Strauss, “New York in 1941,” in The View from Afar, London, Basic Books, 1985, pp. 258-267.

Carlos David Londono Sulkin, “Moral Sources and the Reproduction of the Amazonian Package,” Current Anthropology, vol. 58, no. 4, 2017, pp. 477-501.

Georges Marcus and Michael Fischer (eds.), Anthropologie as Culture Critique: An Experimental Moment in the Human Sciences, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1986.

Birgit Meyer, “In-between: Studying Lived Plurality from the Interstice,” Material Religion, vol. 20, no. 5, 2024, p. 398-401. https://doi.org/10.1080/17432200.2024.2425195

Annemarie Mol, The Body Multiple: Ontology in Medical Practice, Durham, Duke University Press, 2002.

Isak Niehaus, Witchcraft and a Life in the New South Africa, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press with the International African Institute, 2013.

Morten Axel Pedersen, Not Quite Shamans-Spirit Worlds and Political Lives in Northern Mongolia, Ithaca, Cornell University Press, 2011.

Marshall Sahlins, “Foreword,” in Philippe Descola, Beyond Nature and Culture, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2013, pp. xi-xiv.

Seteney Shami, “Circassian Encounters: The Self and the Other and the Production of the Homeland in the North Caucasus,” in Brigit Meyer and Peter Geschiere (eds.), Globalization and Identity – Dialectics of Flow and Closure, London, Blackwell, 1999, pp. 17-47.

Marilyn Strathern, Reproducing the Future: Anthropology, Kinship, and the New Reproductive Technologies, London, Routledge, 1992.

Joseph Tonda, Le Souverain moderne, Paris, Karthala, 2005. (translated as Modern Sovereign – The Body of Power in Central Africa, Delhi/Chicago, Seagull, 2020).

Anna Tsing, Friction - An Ethnography of Global Connection, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2005.

Anna Tsing, “A Multispecies Ontological Turn?” in Keiichi Omura et al. (eds.), The World Multiple. Quotidian Politics of Knowing and Generating Entangled Worlds, London, Routledge, 2019, pp. 233-247.

Jan Vansina, Paths in the Rainforests – Toward a History of Political Tradition in Equatorial Africa, Madison, The University of Wisconsin Press, 1990.

Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “Images of Nature and Society in Amazonian Study,” Annual Review of Anthropology, no. 25, 1996, pp. 179-200.

Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “Cosmological deixis and Amerindian perspectivism,” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, vol. 4, no. 3, 1998, p. 469-548.

Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “Speech at Anthropology and Science Conference,” Manchester Papers in Social Anthropology, no. 7, 2003.

Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, Métaphysiques cannibales : Lignes d’anthropologie structurale, Paris, PUF, 2009.

Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “Intensive Filiation and Demonic Alliance,” in Casper Bruun Jensen and Kjetil Rödje (eds.), Deleuzian Intersections: Science, Technology and Anthropology, Oxford, Berghahn Books, 2010, pp. 219-255.

Eduardo Viveiros de Castro, “Cosmological perspectivism in Amazonia and elsewhere,” HAU: Masterclass Series, no. 1, 2012, pp. 45-168.

Richard Werbner, Anthropology after Gluckman – The Manchester School, Colonial and Postcolonial Transformations, Manchester, Manchester University Press, 2020.