Defining political socialisation can seem simple at first glance. Socialisation refers to all the processes through which society constructs individuals and all the learning processes that make them into who they are1. Political socialisation therefore refers to the specific processes that take place through political agencies and/or that translate into political practices and representations2. While this general definition can be considered established, it is actually more interesting to problematise than to posit. It is possible to reach beyond the research explicitly designated as relating to ‘political socialisation’ (understood as the family transmission of political, and above all voting, preferences and behaviours during childhood) by exploring the two terms making up the expression and taking into account a range of studies studying processes of socialisation in relation to the political world that do not necessarily use that label. Building out from classic definitions of the question, put forward from the 1960s onwards, we will show how this issue is currently being renewed – or could potentially be renewed – by shifting focus to look at both terms contained in the expression ‘political socialisation’. This means analysing the moments and agents of political socialisation processes in more detail and also problematising the content, scope, and definition of the political.

Jacques Jordaens, « Comme les vieux ont chanté, ainsi les jeunes jouent de la flûte »,

Les jeunes piaillent comme chantent les vieux, 1645, Beaux-Arts museum, Valenciennes.

Family transmission of voting preference

The oldest – and from that point of view ‘classic’ – discussions of political socialisation focused on a question that has still not been fully answered, despite the many extended ways it has been addressed: to what extent do processes of family transmission during so-called ‘primary’ socialisation explain political practices and orientations in adulthood?

The seminal works. The formation of attitudes and the stability of political systems

Research on political socialisation, like research on political attitudes, began in the United States in the early 1960s at the intersection of political science and behavioural psychology3. Early studies focused on children’s knowledge and opinions about political institutions and figures (particularly the president) and the family transmission of voting preferences. Above all, research examined the formation of political attitudes, which were central for behaviourists because, in their view, they were a key factor in explaining political and voting behaviour. In a sense, this was the childhood branch of the study of political attitudes, which also explains why women largely came to dominate the field. In France, Charles Roig and Françoise Billon-Grand took up these approaches in the same terms (the ‘study of the formation of political attitudes in France’) 4. Based on a questionnaire survey, they revealed three determinants of interest in politics. First, boys were more interested in social and political life, while girls were more focused on the private sphere and could not identify with any major female political figures. Second and third, age and the family’s socio-cultural level both influenced whether a child developed an interest in the political world. Family political socialisation then came to be the central focus of the Michigan school’s analyses of voting behaviours. Unlike the Columbia school, which gave precedence to people’s social groups, these authors forged the concept of ‘party identification’ and used polls to show that it was consistent over time and shared within the family 5.

As Virginia Sapiro6, points out, the pioneering works on political socialisation all shared the political and institutional framework of traditional parliamentary democracies with stable and bipolar party systems. Implicitly, they therefore also focused on maintaining this type of political regime through the family transmission of values and expected behaviours. Raewyn Connell has offered a critical review of this research from the 1960s, revisiting her own PhD thesis in that field and indicating that her aim at the time had been to understand the longevity of the conservative post-war government in Australia7. Similarly, the French case was taken as a counter example to the American model in which the stability of the regime could be explained by lasting political attitudes passed down through families during childhood: according to Philippe Converse and Georges Dupeux, the instability of the French party system under the Fourth Republic derived from weaker party identification resulting from political socialisation8.

From the early 1970s onwards, Annick Percheron took up these questions about France and opened up new avenues9. As well as examining identification with a ‘political family’ »10, she looked at the construction of national identification through primary political socialisation and, more broadly, at the acquisition of ‘political tools’ before the age of 10. Beyond the simple, almost academic, question of political knowledge, she examined the values and conceptions of the world that children form, in which religion plays an important role. At the beginning of the 1980s, criticism and discussion of the initial formulations of ‘political socialisation’ contributed to renewing critical thinking in the field11. In 1982, the founding idea that preferences acquired in childhood shape adults’ political ideas and restrict the possibility of change was called into question in the field of behavioural psychology12. In 1987, Raewyn Connell published an article on the ‘failure’ of the political socialisation paradigm, in which she listed a series of problems that undermined it: it failed to take into account social power relations (class and sex were, at best, considered as group differences); its research methods were too closed, reinforcing the idea of children as passive recipients, which could have been countered to some extent by more qualitative methods; it paid too little attention to practices (as opposed to just ‘attitudes’) because children don’t vote. Annick Percheron, in her introduction to the special issue in which Raewyn Connell’s piece was published, suggested stepping outside a ‘limited and mechanistic’ conception of learning and no longer ‘understanding the political in its narrowest sense’13. She argued that political socialisation was part of the formation of ‘social identity’ through which children learn to mark their belonging to a group14. This conception has three consequences. First, socialisation is not just the accumulation of knowledge; it is not just intellectual, it is subjective as well. Second, it does not provide ready-made behaviour: there’s no direct and simple relationship between children’s attitudes and adults’ behaviour. Finally, Annick Percheron underlined that the homogeneity of the ‘socialisation milieu’ determines ‘the success with which family values and norms are transmitted’. According to her, comparison between her results for the 1970s and 1980s showed that this ‘success’ was increasingly rare.

Current developments: children, (young people), school, and family

Today, family and school remain the main loci for studying children’s political socialisation 15. Moreover, this initial question of the formation of political attitudes has mainly been pursued by ‘political psychology’ in relation to theories and research about children’s cognitive development. Given that the issue is mainly explored within this discipline, there has been little examination of the role of social characteristics in the process of political socialisation, which others have highlighted.

Daniel Gaxie’s works show that there are inequalities in access to understanding of political issues and that the sense of political competence people have depends on their social class, sex and age16. In the United States, since the early 1980s, the impact that families’ economic and social characteristics have on political socialisation has also been examined. Russell J. Dalton, for example, has shown that successive generations share the same economic and social conditions, which contributes to parents influencing their children’s values – he calls this the ‘social milieu pathway’17. This issue has been reframed in American political science in terms of the transmission of cultural capital, which is argued to promote the transmission of encouragement of political participation 18.

Alice Simon’s current work with primary school children in France indicates that, at the age of 8, differences in political knowledge are shaped by social factors (attending a school in a well-off area, being French-born, growing up in a family of media consumers)19. These results corroborate those of a German study drawing on questions put to 700 children at the beginning and end of their first year of primary school, which showed ‘low levels of political knowledge and issue awareness’ among children from ethnic minorities or from less developed socioeconomic neighbourhoods, and also among girls20. Moreover, these disparities in political competence did not disappear at the end of the year – in other words, the gap was not closed by school.

Anne Muxel’s works have demonstrated that family is the locus for gender-differentiated primary political socialisation, marked by ‘the prevalence of a male model for interpreting interest and engagement in politics’21. Boys’ politicisation takes place earlier: until age 11-12, they demonstrate more interest in, and knowledge of, politics. At puberty, this interest is maintained while girls develop a more distanced attitude or even one that challenges authority. This can be linked both to a traditional gendered division of interests and to a stronger critical attitude towards politics among women. Moreover, girls indicate that their father is the most important figure in their political socialisation. Conversely, for Alan S. Zuckerman, Josip Dasovic, and Jennifer Fitzgerald 22, – whose work focuses on the dynamics of family transmission of party preference in Germany and Great Britain – mothers and wives are at the heart of these dynamics. Their book explores new directions of study: for example, the influence of young adults on their parents (and above all their mothers) or the effects of women’s party membership on all the other members of the family.

Oh no! I have forgotten to socialize the children, drawing.

Source : Blogspot.

Political socialisation is one of the rare fields in which the specific effects of socialisation according to class and sex have been examined. According to Jean-Claude Passeron and François Singly’s work23, when it comes to interest in politics, the intersection of these two ‘variables’ does not create a univocal cumulative effect. Overall, male children do tend to be more interested in politics than their female counterparts and the same goes for children from higher social classes compared to lower social classes. But girls from a higher social background do not show more interest in politics than girls from the salaried middle-classes, who in turn show more interest than boys from their own social class. This kind of investigation has not been reproduced since.

Very few studies have been specifically devoted to the political socialisation of children from ethnic minorities. In France, Asmaa Jaber conducted interviews with second-generation parents and children of North African origin during the 2012 presidential campaign24. Her results showed that these children followed and knew about both French and ‘Arab’ political current affairs (via the television, in particular) and underlined the important role played by ‘legitimist’ discourse about political institutions, largely conveyed by school. As for Vincent Tournier, based on a questionnaire targeting young people between 13 and 19 in Grenoble, he examined the existence of a political socialisation specific to young Muslims. According to him, this socialisation is marked by ‘a more frequent feeling of injustice, […] a stronger politicisation, a certain value placed on violence, and a conflictual relationship to authority, as embodied by school or the police’25. In research looking at the 19th and 20th centuries, Yves Deloye underscores that ‘for many French citizens at the end of the 19th century, civic socialisation was inextricably linked to religious socialisation which has continued in a lasting way to serve as a matrix (in terms of both cognition and identity) for political socialisation’26. Annick Percheron also points to the role played by religion in forming family values. Similarly, Anne Muxel underlines that ‘it is political and religious convictions which, still today, are passed down the best’ 27. Even though investigations into voting tendencies testify persistently to the role of the religious variable, no studies have been conducted on the processes of socialisation specific to belonging to the Christian religion and the ways in which these processes orient votes toward the right wing in all European countries. The effects of religion, migration history, skin colour, or place of residence on the political socialisation of children at home and at school therefore remain to be explored, along with the ways in which they intersect with social class and sex.

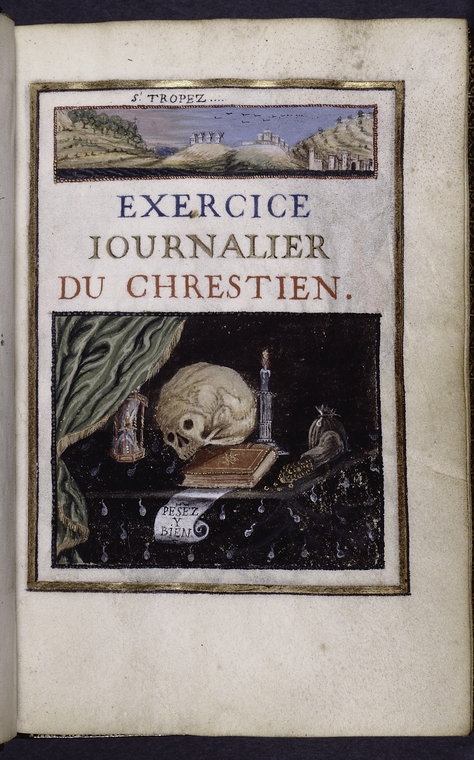

“The day-to-day exercice of the Christian”, Spencer Collection, The New York Public Library Digital Collections, 1650 - 1699.

Moments and Agents of Political socialisation

Building out from the question of transmission, raised by this ‘strong core’ of political socialisation, there is much to gain from extending and refining analysis, giving focus to other moments and other agents of political socialisation.

Childhood and youth: socialisation outside the family

First, it is necessary to take on board one of the accepted facts of the sociology of primary socialisation, i.e. that the latter is ‘plural’ and not limited to family or even to parents. Everything that takes place during in childhood does not necessarily take place in the family. Following the example of studies in the sociology of socialisation focusing on the transmission of academic resources and cultural capital28, it would be interesting to analyse in greater detail the influence of the extended family (grandparents, uncles and aunts, etc. when there is ‘time and occasion for socialisation’) as well as that of siblings. Similarly, socialisation needs to be studied in terms of peers. There is every reason to believe that the latter play an important role, although quantifying that role remains difficult29. It would also be useful to continue examining the influence of specific cultural industries, for example the ‘Guignols de l’info’ television show studied by Vincent Tournier (a satirical puppet show with substantial impact on French popular culture)30.

While the role of school in primary political socialisation is considered self-evident – insofar as level of education (in other words, time spent at school) accounts for political preferences and behaviours – it nonetheless remains under-analysed. Wilfried Lignier and Julie Pagis’s on-going study shows that the famous ‘left-right’ divide is also learnt in the classroom and initially has a very academic meaning. It also reveals that children transpose categories they internalise at school onto the political world31.

“L'école d'antan”, tableau, Talmont-17 museum ; “Les grenouilles à l'école”. Grenouilles naturalisées par le capitaine François Perrier (1813-1860) entre 1853 et 1860, Historic Museum of Estavayer-le-lac, Suisse.

Source : Ressources éducatives.

Later in the school career, Alexandra Oeser has examined the influence that school has in Germany on ways of understanding the Shoah. While boys at gymnasium (selective secondary school) are generally interested in history from the point of view of fighting, weapons, leaders, and victors, when it comes to the Shoah, their relationship to history aligns with that of girls, which is more focused on ordinary individuals and victims, because this is expected by the school institution32.

Everything that takes place in childhood certainly does not only take place within the family. Similarly, though, not everything is decided in childhood. In terms of politics too, processes of socialisation take place during adulthood, beyond the reach of the two main agents at play in childhood i.e. family and school33. The issue at stake is therefore shifting perspective from the initial time of socialisation and looking to secondary socialisation(s). However, as Roberta Sigel notes in an edited volume devoted to this topic at the end of the 1980s in the United States: ‘Attention to political socialization over the entire life span […] is still the exception rather than the rule’ 34. In the book, aside from age (a mixture of growing older and changes in social position, the complexity of which is recognised), the agents of adult political socialisation foregrounded are the world of work, social movements, and traumatic events. These three agents can also be found in the research conducted in France on adult political socialisation – particularly in the case of militant socialisation, which is now attested and the processes of which are better known.

Militant organisations as agents of (political) socialisation

The communist case offers an exemplary illustration of how ‘activists are shaped by organisations’35. The institutional work that constructs a ‘communist subject’36 takes many forms. Political transmission is clear in the PCF (French Communist Party) ‘schools’, that have been organised from the 1920s onwards in France: these agents of ‘communist socialisation’37 take school socialisation as their explicit model38. Communist organisations also work on individuals through their biographies, in other words their conceptions of themselves and the ways they present themselves in official institutional biographies39. ‘Radical’ political organisations are also the locus and the matrix for specific and particularly profound processes of engagement (characterised by the closed and exclusive, or even secret or clandestine, nature of the group) as well as specific processes of disengagement (due to the powerful biographical disruption created by joining and leaving the group)40.

Summer Camp, French Communist Party, 2012.

Source : PCF.

Beyond these examples and the ‘magnifying effects’41 they have on processes of socialisation, the way militant organisations create specific political dispositions among their members can be broached by looking at more informal and less controlled institutions, moments, or situations. In political party youth organisations, for example, peer socialisation operates discretely but powerfully during summer camps or summer schools, over breakfast and in political meetings, while eating croissants and while making envelopes42.

Young Greens, Summer Camp, Lorient, 2016.

Moreover, political agents of socialisation provide more than just political dispositions. Militant organisations, particularly workers’ organisations, can provide substitute academic capital to their members43. Through diffuse requirements and through explicitly academic institutions, the PCF constitutes a locus for accumulating academic and cultural skills44. Militant socialisation can, moreover, translate into specific relationships between the working classes and the administration45 Among postal workers, for example, it can generate the disposition to appreciate ‘a job that allows you to “do something for” other people’ 46. More generally, the research trend focusing on the ‘biographical consequences of engagement’ attempts to piece together the extra-political effects of the learning that takes place through agents of political socialisation47. Julie Pagis has analysed the long-term impact of May 68 from this perspective, as a combination of effects that are political, but at the same time professional (in that they determine trajectories) and private (in that they influence daily life, views of coupledom, or views of the world). Over recent years, an important contribution to these questions can be found in research into feminist movements, which have had a clear impact on the ‘private’ sphere, and into the dissemination of these ideas beyond simply female activists48. Moreover, when militants change direction, this also highlights how organisational know-how can be of value in other activities (and is not only actualized in a political context)49.

Socialisation to working in politics

Militant socialisation also raises the question of learning to work in politics itself, this ‘profession that cannot be learnt’50. Lucie Bargel has highlighted the implicit learning that takes place within party organisations, which tend to reproduce social- and gender-based selection rationales in two ways 51. On the one hand, tacitly, because the learning process is based on covert expectations, on unevenly distributed dispositions – for political discussion, for enjoying learning, for speaking in public, etc. – and also on interpersonal ties organised around homophily, which encourages the reproduction of the group’s social and gendered make-up. On the other hand, this selection also takes place more explicitly and actively, through ‘old timers’ identifying the profiles likely to rise in the ranks and meet the (more or less intense) need to renew the ‘executive’. Learning the rules of the political game begins long before access to elected office and the process is strongly shaped by social- and gender-based selection rationales.

Socialisation to working in politics continues with access to each new job or elected position52. Recently, studies on this topic have, on the one hand, explored the effects of the French law on political parity (ensuring equal access to political representation for both men and women)53 and, on the other hand, analysed European political staff. In a way, the research conducted on women who entered the political field when the law on parity was passed has reminded us of the importance of what happens before elected office. The women chosen by the chief candidates on the party list were most often laywomen when it came to politics, with no party experience. For this reason, they were considered as representative of civil society and local communities, however their lack of prior political socialisation poses specific problems for these elected women. The differentiated treatment they receive during electoral campaigns and within elected bodies54, contributes to creating a gendered socialisation to working in politics, which leads to them leaving politics more often than men55.

Studies focused on how political roles are learnt have also developed around the issue of socialisation to European institutions56, among both elected officials and civil servants. Unequal familiarity with European institutions clearly emerges as a founding logic underpinning the ‘field of Eurocracy’ 57, to the extent that longevity in these institutions is one of the main factors explaining conceptions and practices in European action58. These studies are also original in that they study the socialisation of non-elected political staff (high-ranking civil servants, people who work with elected officials) who tend to remain invisible when it comes to studies on national political staff59.

Learning politics at work

It is also important to take the measure of how work, as an institution, as an activity, and as a network of sociability, constitutes an important, albeit under-studied, agent of political socialisation. Qualitative approaches, based on individual cases and trajectories, are able to show us ‘how the experience of work produces socialisation and therefore political socialisation, in difficult times of strikes and work conflicts, of course, but also in calmer times of work routines’60.

Philippe Gottraux and Cécile Péchu analysed the trajectory of one man from this perspective – ‘Jacques’, a small shopkeeper who shifted from the left wing to the populist right – arguing it revealed the effect of professional socialisation on political positions and the relationship to politics. Progressively, Jacques’ long-standing commitment to the left wing, explained by his primary family political socialisation, conflicted with his professional activity (he ran a hardware and herbalist’s shop in Geneva). After years of belonging to the Socialist Party, he eventually joined the Swiss Democratic Union of the Centre party (to ‘the right of the right’). This professional political socialisation took place through the influence of his profession, the strained context in his economic sector, and the status and representations related to his profession, from his own perspective and that of others61. In the same edited volume, aimed at ‘understanding the scope of political socialisation in the workplace62, Julien Mischi highlights the effects of the politicisation of professional socialisations, in the case of workers’ activism (where dispositions for collective action are acquired, in particular, through union activity) and within groups of hunters. In this context, professional socialisation is a key factor in understanding how the working classes become involved in collective action. Within hunters’ groups, discussions are clearly marked by registers and categories for understanding reality that come from the factory (anti-boss rhetoric) or from the working world (being able to hunt is presented as linked to social victories and paid holiday)63. Elise Cruzel also discusses the case of Attac activists, showing how a process of secondary socialisation – that is both union- and professionally-based – explains the construction of political choices and preferences64.

The role of events in secondary political socialisation

Finally, phenomena of secondary political socialisation can also exist outside the world of work or organisations as institutionalised as activist movements. In the analyses brought together by Roberta Sigel, ‘traumatic events’ (war or terrorism) are also presented as agents of socialisation and individual change. For an event to have the power to socialise it does not, however, have to be what a socio-psychological approach would qualify as ‘traumatic’. While Annick Percheron has analysed the profound reorganisation of systems of reference among people who lived through the Algerian war – arguing that the war concomitantly produced both the generation of Algerian Algeria and the generation of French Algeria65 –, Olivier Ihl has highlighted the socialising effect of a much broader spectrum of political events, including the most everyday of them.

Muslim Street Protest, Paris, 1961. See the video on INA.

The effect of political events on the formation of attitudes shows, once again, that political socialisation is by no means limited to childhood and adolescence. ‘Political experiences’ – electoral campaigns, military operations, or the actions/death of a ‘great man’ – offer a certain number of ‘socialisation opportunities’. These can occur through direct contact with a collective dynamic (protests, electoral participation, activism), through exposure to media traffic about them (press campaigns linked to a political scandal, televised debates), or through interpersonal relationships that propound ways of understanding these actions (family discussions, heated remarks in the workplace). These experiences can then ‘become emblematic and, as such, turn into agents of socialisation in their own right due to the work that ‘exemplary agents’ and ‘reputational entrepreneurs’ (such as journalists, historians or teachers) do in terms of the ‘processing’ and transmission of the event66.

In this way, it seems that North American African Americans who grew up during the civil rights movement talk more than those from other generations about a politically stimulating family environment and display greater levels of political participation67. However, rather than referring to the socialising effect that an event has on the undifferentiated mass of people who experienced it, it would be more appropriate to refer to socialising ‘effects’ in the plural. This is demonstrated by Julie Pagis’s typology of the socialising effects resulting from participation in the events of May and June 1968 in France: ‘depending on previous activist resources and the degree of exposition to the event, the latter be a source of different kinds of political socialisation – maintaining, reinforcing, creating awareness of, or converting previous political dispositions or convictions’ 68. Moreover, the May ’68 ‘generations’ are also ‘gendered political generations’ due to the differences in event socialisation among men and women69.

Upraisings, Jeu de Paume - Concorde, Paris / Teaser.

Problematising the scope and definition of the ‘political’

In short, an initial way of analysing the classic question of political socialisation in greater depth consists in investigating moments and agents of political socialisation outside primary family socialisation. A second avenue to explore to accomplish this concerns the definition of the ‘political’ itself and its possible extensions.

Socialisation to (and through) engagement

Taking this approach means looking to the boundaries of conventional participation, or even looking outside it, and analysing the cases of very varied associations, collectives, movements, and organisations. In order to ‘address how socialisation contributes to explaining engagement in causes with specific stakes’ – as opposed to explaining general political participation or positions on the left-right axis – Lilian Mathieu examined the case of engagement in a regional collective of the Education without Borders network70. He highlighted three topics of analysis. First, the conditions necessary for people to rally: recruitment tends to be female, closely linked to social work, and (like in movements defending undocumented immigrants), mainly from the salaried middle classes in the small intellectual bourgeoisie, with rising social mobility, but also predisposing family, school, or religious socialisation. Second, the processes through which dispositions and skills are activated when people join the network. Third, the way these dispositions and skills are reworked after a trajectory through that network (learning technical and legal skills, or the rationalised management of indignation).

Two main research directions can be identified where these issues are concerned: studying processes of socialisation ‘to’ engagement and processes of socialisation ‘through’ engagement, calling on and confronting the different definitions of the political that play out in that context. Where the predisposition to engagement is concerned, religious socialisation and the relationship to religion should be taken into account in the context of a ‘politicisation of religious engagement’71 that we are starting to better understand. While Catholic socialisation plays a role in explaining conventional political participation, for example in the case of Catholic families and the Bayrou vote72, it can also offer a way of understanding participation in non-religious humanitarian NGOs. Johanna Siméant has examined how a religious socialisation made up of ‘dispositions, skills, and appetence’ and not limited to a system of beliefs, but also involving practices and practical habits, can explain humanitarian engagement and the relationship towards it. This remains the case despite the rejection of politics and religion within these organisations73. Moreover, Florence Joshua has shown that one of the rationales underpinning revolutionary engagement in the 1960s was fuelled by ‘the anger and desire for vengeance’ of young people from Jewish families affected by the Shoah74.

Just like the case of militant socialisation, being part of a collective – along with the processes involved in ‘engagement’ – then produce ‘dispositions to act or believe’ 76, which broaden and complicate the definition of what is ‘political’. Elsa Rambaud has shown how a ‘process constructing and instilling a system of values and practices’ operates within Doctors without Borders; a critical grammar that is the result of a learning process and the product of socialisation76.

National socialisation

Studies focusing on political socialisation in the strictest sense of term – i.e. state-centred – initially examined several aspects of the issue: the construction of a relationship to representative political institutions, to actors in the electoral game and to a sense of national belonging77. In Annick Percheron’s view, during political socialisation, children acquire the principles of the political game, a sense of civic duty, a national identity, and a sense of belonging to a national community. The latter derive from recourse to ‘tradition’ as materialised in daily habits or rituals, particularly at school 79. National socialisation has since largely disappeared from studies on political socialisation.

While education plays an important role in studying nationalism, the question of the transmission of national identity is not expressed in terms of socialisation. There are two possible reasons for this. First, specialists of nationalism tend to focus on the more explicit ways in which national belonging is constructed and maintained (the school system 80) or on the more legitimate forms this takes (novels, the press, etc.80). Second, they mainly focus attention on the deliberate and political construction of this national idea81, at the level of the State, giving little emphasis to the ways the nationalist cultural offering is received and appropriated. Recent evolutions in literature on nationalism, however, have paved the way for a new examination of the socialisation issue. Since the mid-1990s, the emphasis given to ordinary nationalism 83 has encouraged analysis of less explicit and more everyday forms of nationalism, among ordinary actors83. Anders Linde-Laursen, for example, has looked at how Danes and Swedes learn different ways of doing the washing-up84. The question is less about understanding ‘why’ nations were created and more about understanding ‘how’ they continue to exist. Although some of these studies, which could be attached to the field of Cultural Studies, focus on cultural products in circulation (films, football matches, etc.) without looking at their reception, others, more often linked to anthropology, do analyse this, mainly among children and young people85.

This is the thread that Katharine Throssell tugs on in one of the rare recent studies explicitly devoted to national socialisation86. Her study lies at the intersection of work on nationalism and work on political psychology, the latter of which has continued to explore the development of relationships to the nation, mainly through investigations with children and through indicators such as recognising ones ‘own’ flag. She shows how early and complex national identification is among English and French primary school children, and reveals its consequences on their conceptions of belonging to the same group.

Katharine Throssell, Child and Nation. A Study of Political Socialisation and Banal Nationalism in France and England, Berne, Peter Lang, 2015. Flags on the cover.

Insofar as nationalism can be considered as the transformation of an arbitrary political entity (the State) into a naturalised social and cultural group (the Nation), the formation of relationships to the State and its different dimensions – local administration 87, taxes 89, etc. – could also be the topic of investigations in terms of national socialisation. Finally, the notion of ‘national habitus’ used by Norbert Elias and then Gérard Noiriel89, also encourages us to question the conditions in which such a habitus is formed, along with national dispositions that are produced by individual trajectories, while simultaneously producing them. Situations of migration offer a key locus for observing processes of national re-socialisation90 or ‘sociological doubling-up’91. Patrick Weil has pointed out that the idea of national socialisation is a fundamental principle underpinning French law on nationality, with the latter attributed according to residence and birth, in other words, time spent in the country92.

Very few studies have looked at the political effects, electorally speaking, of the experience of migration. According to Bruce Cain, Roderick Kiewiet, and Carole Uhlaner93, the longer immigrants from Latin America have spent in the United States, the more they will develop an affiliation with the Democratic Party. This phenomenon is even more marked for the second generation. Conversely, immigrants from China, Korea, and South-East Asia will progressively identify with the Republican Party as they become exposed to American political life. The authors explain this is because the former position themselves politically in light of their experience as a minority group, while the latter base their electoral choice on the United States’ foreign policy.

The links between the political and the non-political

A third way of problematising the ‘political’ in political socialisation consists in broaching it as a practical area that interacts with others. We have already seen how the professional world, for example, can be a locus for political socialisation. Broadening this perspective leads us to examine the political effects of non-political socialisation and the non-political effects of political socialisation.

Regarding the potential socialisation influence of events, we used examples of patently political events. However, the experience of handicap or illness could also constitute events likely to change a person’s relationship to militant engagement – for example, with activists in associations fighting AIDS 95 –, and the same is true for breaking with a key institution in primary socialisation (school or the Church, in particular) 96, or a specific relationship to food or animals constructed during primary socialisation96. Furthermore, some studies in American political science have made links between political effects and marital socialisation: Laura Stocker and Kent Jennings have noted, for example, that after marriage the couple’s degree of political participation tends to align97. As for Breanne Fahs, she has underlined that divorced women tend to subscribe more than married women to liberal and feminist values98.

What is ‘political’?

Sophie Maurer outlined in very precise terms the issue of ‘what political socialisation covers’ in her 2000 overview of the question. In her view, the debate is organised around two theories: ‘the theory that argues that a specifically political socialisation does exist, which relies on distinct mechanisms and passes through distinct channels’ (defended, in particular, by Annick Percheron) and ‘the theory that states, on the contrary, that the ‘political’ is just another word for the ‘social’ and that denies the existence of specifically political socialisation’ (this equating of the political order with the social order is ascribed to Pierre Bourdieu)100. Sophie Maurer suggests considering these two conceptions as two levels that make up individuals’ relationship to the political. The first level – the relationship to politics as a specialised world (parties, ideologies, elections) – is learnt through specific political socialisation, particularly at school, and is officially normative. The second level – individuals’ political relationship to the social world – extends beyond the political field in the strict sense of the term. It involves representations of social divisions, class relations, and mechanisms for the distribution of wealth, as well as how conflicts are prioritised and different ways of being and doing (speaking, dressing, eating) that position individuals, giving them a particular political place, and constitute a range of social markers likely to be interpreted from a political point of view. Wilfried Lignier and Julie Pagis’s study on how children ‘speak’ and learn the ‘social order’, with its hierarchies, proximities and ‘distances’100, has as much to contribute to the sociology of childhood socialisation as it does to that of political socialisation.

Dialog Between Tristan et Jacques Martin, 1994. See the video on INA.

However, this second level presents the drawback of opening up the field of investigation ‘to infinity’. Sophie Maurer therefore suggests an initial way of restricting it, through the notion of conflict (by defining politics on the basis of diverging interests and therefore power relations). Florence Haegel and Sophie Duchesne101 on the one hand, and Camille Hamidi 103 on the other, have since examined in greater depth this call to identify and define conflict and the rise in the level of generality as markers of the political. This alternative between two conceptions of the ‘political’ in socialisation – one state-centred and the other expressed more in terms of ‘politicisation’ – remains relevant today: it was posited, for example, in the introduction to the 2014 workshop on ‘Examining the notion of political socialisation’103.

Based on the previous examples, we would suggest considering political socialisation as including three dimensions: socialisation to objects that are specific to the political field; socialisation to a ‘mobilised relationship to one’s social condition’, as Yasmine Siblot puts it104, and socialisation to a ‘mobilised’ relationship to social power relations (even when this is not based on direct experience of these relations).

Pursuing research and refining our analysis of processes

Everything points to the need to develop a broad and dynamic understanding of political socialisation. Looking for other agents than the family to account for primary political socialisation; looking at adult secondary socialisation as another moment at which to study socialisation; examining political learning outside the ‘political’ in its strictest sense. All these scientific endeavours go hand-in-hand with a more refined, detailed approach and reflect a broader interest in processes of socialisation themselves. Today, the issue at stake could be approaching and analysing processes of socialisation empirically. This means taking distance from mechanistic determinism (which, for example, simply equates a strong variable and a given political orientation or attitude) and also from empty, unsubstantiated calls for various forms of freedom in political determination (which simply posit the ‘agency’ of actors without defining or demonstrating how the content being passed down is ‘re-appropriated’ or ‘selected’).

With her early calls to take into account the fact that children are not passive beings and to clarify the mechanisms of transmission, Annick Percheron already paved the way for this approach105. However, her positions were coupled with an extremely voluntarist and subjectivist view of the activities of the ‘socialisers’ – i.e. parents with socialisation intentions (whereas a distinction should probably be drawn between parental educational intentions and the partly subconscious and involuntary mechanisms of socialisation) – and the ‘socialised, presented as being able and willing to deal with this transmission in such a way as ‘to construct their personal identity’ by only retaining, for example, ‘part of their heritage’. There is therefore a strong lack of symmetry between the times when socialisation is analysed as the ‘product of transmission’ and those when it becomes a ‘tool for inventing each person’s system of values’106, – and, as such, is less analysed than it is invoked as the social magic of free will. The hiatus between these two analytical registers makes it difficult to link transmission and reception, or tie together different moments of socialisation.

Conversely, in 2002 Daniel Gaxie’s analysis of a series of in-depth interviews showed the links between the different processes of socialisation conditioning political investments and preferences throughout life cycles and the congruency or dissonance between the latter, while also formulating hypotheses about conditions of the hysteresis or, on the contrary, the disappearance of dispositions resulting from primary political socialisation107. In doing so, this research not only addressed the influence of secondary socialisation, it also questioned the synchronic and diachronic links between the different processes making up ‘continuous socialisation’, composed of dispositions that are formed and transformed over a lifetime, in the political field and beyond109. In Florence Haegel and Marie-Claire Lavabre’s work, shifting scale – by focusing on the individual and thereby obtaining localised knowledge about global changes – and using case studies, framed theoretically, enabled them to account for the three moments of political socialisation in the life of one woman named ‘Janine’. These stages were family political socialisation, marital socialisation, and a reverse form of socialisation through the political norms conveyed by her son110.

Following on from Bernard Lahire’s work on the transmission of cultural capital in primary socialisation, the equivalent of political ‘family portraits’110 have yet to be painted. This would allow us to return to an analysis of primary socialisations that is fuelled by interest in the details of how processes function – an interest born, in turn, from taking into account adult socialisations and how they interlink. Taking the most systematic approach possible, this would mean starting by examining family configurations and then asking what is being transmitted and observing how this actually happens. Who are the actors that actually make up the ‘agent’ of socialisation known as the ‘family’ (mother, father, stepmother111, siblings etc.)? Through which concrete practices is the ‘political’ actually transmitted (from family conversations to media use and experience of institutions, or any another practical areas highlighted by the investigation)112? Finally, the aim would be to create the means to offer a sociological analysis of the modes on which this socio-genesis of political dispositions is received and internalised. This is what Camille Masclet does, for example, for a case of transmission of a feminist legacy, showing how, among two siblings who are children of second wave feminists, a distinction can be drawn between the way the sister appropriates this legacy (due to her gender, her professional trajectory, but also the family transmission of academic capital) and the way the brother internalises practical, non reflexive, and more limited dispositions113.

Such an approach could offer a new way of addressing the still-unresolved question of class- and gender-based political socialisation from a perspective closely focused on the actual processes involved and how these intersect. Another potential avenue to explore, provided by sociologies of socialisation, particularly gender-based socialisation, could involve working on atypical cases more: the case of ‘female politicians’ maps onto the classic question of women ‘doing male jobs’ but could raise a more general question about what socialisation processes produce political dispositions that are unexpected, because they are out of sync with the classes (social, gender, religious, etc.) to which someone belongs? Despite the many studies published and the undeniable progress made in analysing political socialisation, what this overview of the topic has revealed above all is just how much we still do not know – including on questions as seemingly ‘classic’ as primary political socialisation, gender socialisation, or national socialisation.

Notes

1

Muriel Darmon, La Socialisation, Paris, Armand Colin, 2016.

2

Lucie Bargel, “Socialisation politique”, Dictionnaire des mouvements sociaux, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 2009, p. 510-517; “Socialisation politique”, Dictionnaire genre & science politique, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 2013, p. 468-480.

3

Herbert Hyman, Political Socialization. A Study in the Psychology of Political Behavior, New York, Free Press, 1959; Fred I. Greenstein, “The Benevolent Leader: Children’s Images of Political Authority”, The American Political Science Review, vol. 54, n° 4, 1960, p. 934-943; Robert D. Hess, David Easton, “The Child’s Changing Image of the President”, Public Opinion Quartely, vol. 24, n° 4, 1960, p. 632-644; David Easton, Jack Dennis, Children in the Political System. Origins of Political Legitimacy, New York, McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1969; M. Kent Jennings, Richard G. Niemi, “The Transmission of Political Values from Parent to Child”, American Political Science Review, vol. 62, n°1, 1968, p. 169-184.

4

Charles Roig, Françoise Billon-Grand, La Socialisation politique des enfants. Contribution à l’étude de la formation des attitudes politiques en France, Paris, Armand Colin, 1968.

5

Angus Campbell, Philip E. Converse, Warren E. Miller, Donald E. Stokes, The American Voter, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1960.

6

Virginia Sapiro, “‘Not your parents’ political socialization: Introduction for a New Generation”, Annual Review of Political Science, vol. 7, no 1, 2004, p. 1-23.

7

Raewyn W. Connell, “Why the ‘Political Socialization’ Paradigm Failed and What Should Replace It”, International Political Science Review / Revue internationale de science politique, vol. 8, no 3, 1987, p. 215-223.

8

Philip E. Converse, Georges Dupeux, “Politicization of the Electorate in France and the United States”, Public Opinion Quarterly, vol. 26, no 1, 1962, p. 1-23.

9

Annick Percheron, L’Univers politique des enfants, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 1974; “La socialisation politique: défense et illustration”, in M. Grawitz, J. Leca (dir.), Traité de science politique, vol. 3, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 1985, p. 165-235.

10

On the left or the right, in a form of adaptation of the U.S. Republican/Democrat divide.

11

Annick Percheron, “Les études américaines sur les phénomènes de socialisation politique dans l’impasse? Chronique d’un domaine de recherche”, L’Année sociologique, vol. 31, 1981, p. 69-96.

12

Steven A. Peterson, Albert Somit, “Cognitive Development and Childhood Political Socialization: Questions about the Primacy Principle”, American Behavioral Scientist, vol. 25, no 3, 1982, p. 313-334.

13

Annick Percheron, “La socialisation politique: un domaine de recherche encore à développer”, International Political Science Review / Revue internationale de science politique, vol. 8, n° 3, 1987, p. 199-203.

14

Annick Percheron, “La socialisation politique: un domaine de recherche encore à développer”, International Political Science Review / Revue internationale de science politique, vol. 8, n° 3, 1987, p. 199-203.

15

Simone Abendschön (ed.), Growing Into Politics: Contexts and Timing of Political Socialisation, Colchester, UK, ECPR Press, 2013.

16

Daniel Gaxie, Le Cens caché. Inégalités culturelles et ségrégation politique, Paris, Le Seuil, 1978.

17

Russel J. Dalton, “The Pathways of Parental Socialization”, American Politics Quarterly, vol. 10, n° 2, 1982, p. 139-157.

18

Nancy Burns, Kay Lehman Scholzman, Sidney Verba, Family Ties. Understanding the Intergenerational Transmission of Participation, s.l., Russell Sage Foundation Working Paper Series, 2003.

19

Alice Simon, “Political Competence of Children and Social Background: Results of a Study with French Primary School Children”, communication au Congrès de l’IPSA, 2014.

20

Jan W. van Deth, Simone Abendschön, Meike Vollmar, “Children and Politics. An Empirical Reassessment of Early Political Socialization”, Political Psychology, vol. 32, no 1, 2011, p. 147-174.

21

Anne Muxel, “Socialisation et lien politique”, in T. Blöss (dir.), La Dialectique des rapports hommes-femmes, Paris, PUF, 2001, p. 27-45.

22

Alan S. Zuckerman, Josip Dasovic, Jennifer Fitzgerald, Partisan Families. The Social Logic of Bounded Partisanship in Germany and Britain, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2007.

23

Jean-Claude Passeron, François de Singly, “Différences dans la différence: socialisation de classe et socialisation sexuelle”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 34, no 1, 1984, p. 48-78.

24

Asmaa Jaber, “La socialisation politique enfantine dans des familles d’origine immigrée”, Recherches familiales, n° 12, 2015, p. 247-261.

25

Vincent Tournier, “Modalités et spécificités de la socialisation des jeunes musulmans en France”, Revue française de sociologie, 2011, vol. 52, no 2, p. 311-352.

26

Yves Deloye, “Socialisation religieuse et comportement électoral en France. L’affaire des ‘catéchismes augmentés’ (19e-20esiècles)”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 52, no 2, 2002, p. 179-199.

27

Anne Muxel, Toi, moi et la politique. Amour et convictions, Paris, Le Seuil, 2008.

28

Bernard Lahire, Tableaux de familles (1995) Paris, Le Seuil/Gallimard, 2012.

29

Vincent Tournier’s study involving collège pupils (equiv. years 7 to 10 in the UK or 6th grade to 9th grade in the US) in the Isère department (“Comment le vote vient aux jeunes. L’apprentissage de la norme électorale”, Agora Débats/Jeunesse, n° 51, 2009, p. 79-96) concluded that “the contribution of the peer group appears negligible”. However, it is reasonable to think that the quantitative analysis framework and the questions asked about political discussions with friends only offer an imperfect way of understanding peer socialisation processes operating at collège age.

30

Vincent Tournier, “Les ‘Guignols de l'Info’ et la socialisation politique des jeunes (à travers deux enquêtes iséroises)”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 55, n° 4, 2005, p. 691-724.

31

Wilfried Lignier, Julie Pagis, L'Enfance de l'ordre, Paris, Le Seuil, 2017.

32

Alexandra Oeser, “Genre et enseignement de l’histoire. Étude de cas dans un Gymnasium de la ville de Hambourg”, Sociétés & Représentations, no 24, 2007, p. 111-128.

33

Sébastien Michon is also studying the effects of students’ academic careers on political socialisation: “Les effets des contextes d’études sur la politisation”, Revue française de pédagogie, n° 163, 2008, p. 63-75 (online).

34

Roberta S. Sigel (dir.), Political Learning in Adulthood. A Sourcebook of Theory and Research, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1989.

35

Johanna Siméant, Frédéric Sawicki, “Décloisonner la sociologie de l’engagement militant”, Sociologie du travail, vol. 51, 2009, p. 97-125.

36

Claude Pennetier, Bernard Pudal (dir), Le Sujet communiste. Identités militantes et laboratoires du “moi”, Rennes, PUR, 2014.

37

Nathalie Ethuin, “De l'idéologisation de l'engagement communiste. Fragments d'une enquête sur les écoles du PCF (1970-1990)”, Politix, n° 63, 2003, p. 145-168.

38

Yasmine Siblot, “Ouvriérisme et posture scolaire au PCF. La constitution des écoles élémentaires (1925-1936)”, Politix, no 58, 2002, p. 167-188.

39

Claude Pennetier, Bernard Pudal, “Écrire son autobiographie (les autobiographies communistes d’institution, 1931-1939)”, Genèses, n° 23, 1996, p. 53-75; Ioana Cîrstocea, “‘Soi-même comme un autre’ : l’individu aux prises avec l’encadrement biographique communiste (Roumanie, 1960-1970)”, in C. Pennetier, B. Pudal (ed.), Le Sujet communiste. Identités militantes et laboratoires du « moi », Rennes, PUR, Rennes, 2014, p. 59-78.

40

Isabelle Sommier, “Engagement radical, désengagement et déradicalisation”, Lien social et politiques, n° 68, 2012, p. 15-35; Olivier Fillieule, “Le désengagement d’organisations radicales”, Lien social et politiques, n° 68, 2012, p. 37-59. These two articles were published in an issue entitled “Radicalités et radicalisations”, edited by Pascal Dufour, Graeme Hayes, and Sylvie Ollitrault.

41

Isabelle Sommier, “Engagement radical, désengagement et déradicalisation”, Lien social et politiques, n° 68, 2012, p. 24.

42

Lucie Bargel, Jeunes socialistes / Jeunes UMP. Lieux et processus de socialisation politique, Paris, Dalloz, 2009.

43

Daniel Gaxie, “Économie des partis et rétributions du militantisme”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 27, no 1, 1977, p. 123-154.

44

Bernard Pudal, Prendre parti, Paris, Presses de la FNSP, Paris, 1989; Claude Pennetier, Bernard Pudal, “La Certification scolaire”, Politix, n° 35, 1996, p. 69-88.

45

Yasmine Siblot, Faire valoir ses droits au quotidien. Les services publics dans les quartiers populaires, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 2006.

46

Marie Cartier, Les Facteurs et leurs tournées. Un service public au quotidien, Paris, La Découverte, 2003.

47

Catherine Leclercq, Julie Pagis, “Les incidences biographiques de l'engagement. Socialisations militantes et mobilité sociale”, Sociétés contemporaines, n° 84, 2011, p. 5-23.

48

See all publications in n° 109 of Politix, 2015 (special section “Appropriations ordinaires des idées féministes”) Catherine Achin, Delphine Naudier, “Trajectoires de femmes ‘ordinaires’ dans les années 1970”, Sociologie, vol. 1, no 1, 2010, p. 77-93; Alban Jacquemart, “L’engagement féministe des hommes, entre contestation et reproduction du genre”, Cahiers du Genre, no 55, 2013, p. 49-63.

49

Annie Collovald, Erik Neveu, “Le néo-polar. Du gauchisme politique au gauchisme littéraire”, Sociétés & Représentations, n° 11, 2001, p. 77-93; Sylvie Tissot, Christophe Gaubert, Marie-Hélène Lechien (dir.), Reconversions militantes, Limoges, Presses de l’université de Limoges, 2005.

50

Jacques Lagroye, “Être du métier”, Politix, no 28, 1994, p. 5-15.

51

Lucie Bargel, Jeunes socialistes / Jeunes UMP. Lieux et processus de socialisation politique, Paris, Dalloz, 2009.

52

Olivier Nay, “L’institutionnalisation de la région comme apprentissage des rôles. Le cas des conseillers régionaux”, Politix, no 38, 1997, p. 18-46. See all the articles in this issue devoted to “L’institution des rôles politiques”.

53

Éric Fassin, Christine Guionnet (dir.), “Dossier ‘la parité en pratiques’”, Politix, no 60, 2002; Catherine Achin, Lucie Bargel, Delphine Dulong, Éric Fassin, et al., Sexes, genre et politique, Paris, Economica, 2007; Maud Navarre, Devenir élue. Genre et carrière politique, Paris, PUR, 2015.

54

Delphine Dulong, Frédérique Matonti, “Comment devenir un(e) professionnel(le) de la politique? L’apprentissage des rôles au Conseil régional d’Île-de-France”, Sociétés & Représentations, no 24, 2007, p. 251-267.

55

Catherine Achin, Sandrine Lévêque, “La parité sous contrôle”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 204, 2014, p. 118-137.

56

Anne-Catherine Wagner, “Syndicalistes européens”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, no 155, 2004, p. 12-33; Hélène Michel, Cécile Robert (dir.), La Fabrique des “Européens”. Processus de socialisation et construction européenne, Strasbourg, Presses universitaires de Strasbourg, 2010; Willy Beauvallet, Sébastien Michon, “Professionalization and Socialization of the Members of the European Parliament”, French Politics, vol. 8, no 2, 2010, p. 145-165; Lucyna Derkacz, Socialisation politique au Parlement européen. L’exemple des eurodéputés polonais, Windhof, Promoculture, 2013.

57

Didier Georgakakis (dir.), Le Champ de l’Eurocratie. Une sociologie politique du personnel de l’UE, Paris, Economica, 2012.

58

Didier Georgakakis, Marine de Lassalle, “Genèse et structure d’un capital institutionnel européen”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, no 166-167, 2007, p. 38-53.

59

See However Jean-Luc Bodiguel, “La socialisation des hauts fonctionnaires. Les directeurs d’administration centrale”, in CURAPP (dir.), La Haute administration et la politique, Paris, PUF, 1986, p. 81-99; Guillaume Courty (dir.), Le Travail de collaboration avec les élus, Paris, Michel Houdiard Éditeur, 2005; Patrick Le Lidec, Didier Demazière (dir.), Les Mondes du travail politique. Les élus et leurs entourages, Rennes, PUR, 2014; Grégory Daho, “La socialisation entre groupes professionnels de la politique étrangère”, Cultures & Conflits, no 98, 2015, p. 101-131.

60

Olivier Fillieule, “Postface. Travail, famille, politisation”, in I. Sainsaulieu, M. Surdez (dir.), Sens politiques du travail, Paris, Armand Colin, 2012, p. 350.

61

Philippe Gottraux, Cécile Péchu, “Le réalignement politique à droite d’un petit commerçant: complexité de l’analyse des ‘dispositions politiques’”, in I. Sainsaulieu, M. Surdez (dir.), Sens politiques du travail, Paris, Armand Colin, 2012, p. 155-170.

62

Ivan Sainsaulieu, Muriel Surdez (dir.), Sens politiques du travail, Paris, Armand Colin, 2012, p. 18.

64

Élise Cruzel, “‘Passer à l’Attac’: éléments pour l’analyse d’un engagement altermondialiste”, Politix, n° 68, 2004, p. 135-163.

65

Annick Percheron, La Socialisation politique, Paris, Armand Colin, 1993, p. 173-189.

67

Nancy Burns, Kay Lehman Scholzman, Sidney Verba, Family Ties: Understanding the Intergenerational Transmission of Participation | Russell Sage Foundation, s.l., Russell Sage Foundation Working Paper Series, 2003.

68

Julie Pagis, Mai 68, un pavé dans leur histoire. Événements et socialisation politique, Paris, Presses de la FNSP, 2014, p. 76.

71

Julie Pagis, “La politisation d’engagements religieux”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 60, no 1, 2010, p. 61-89.

72

Julien Fretel, “Quand les catholiques vont au parti”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 155, 2004, p. 76-89.

73

Johanna Siméant, “Socialisation catholique et biens de salut dans quatre ONG humanitaires françaises”, Le Mouvement social, n° 227, 2009, p. 101-122.

74

Florence Joshua, “‘Nous vengerons nos pères…’ De l’usage de la colère dans les organisations politiques d’extrême-gauche dans les années 1968”, Politix, n° 104, 2014, p. 203-233.

76

Bernard Lahire, Portraits sociologiques, Paris, Nathan, 2002.

76

Elsa Rambaud, “L'organisation sociale de la critique à Médecins sans frontières”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 59, n° 4, 2009, p. 723-756.

77

Jean Piaget, “Le développement, chez l’enfant, de l’idée de patrie et des relations avec l’étranger”, in Travaux de Sciences Sociales, Paris, Droz, 1977, p. 283-306.

79

Annick Percheron, La Socialisation politique, Paris, Armand Colin, 1993.

80

Ernest Gellner, Nations and Nationalism, Ithaca-NY, Cornell University Press, 1983.

80

Benedict R. Anderson, Imagined Communities Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, London-New York, Verso, 1983.

81

Anne-Marie Thiesse, La Création des identités nationales. Europe XVIIIe-XXe siècle, Paris, Le Seuil, 1999.

83

Michael Billig, Banal Nationalism, Newcastel, SAGE, 1995.

83

Jon E. Fox, Cynthia Miller-Idriss, “Everyday nationhood”, Ethnicities, vol. 8, no 4, 2008, p. 536-563; Michael Skey, National Belonging and Everyday Life. The Significance of Nationhood in an Uncertain World, New York, Palgrave Macmillan, 2011.

84

Anders Linde-Laursen, “Nationalization of trivialities: how cleaning becomes an identity marker in the encounter of Swedes and Danes”, Ethnos, vol. 58, no 3-4, 1993, p. 275-293.

85

Tomke Lask, “‘Baguette heads’ and ‘spiked helmets’: children’s construction of nationality at the German-French border”, in H. Donnan, T. M. Wilson (dir.), Border Approaches. Anthropological Perspectives on Frontiers, Lanham, Anthropological Association of Ireland-University Press of America, 1994, p. 63-73; Marco Antonsich, “The ‘Everyday’ of Banal Nationalism – Ordinary People’s Views on Italy and Italian”, Political Geography, 2015, p. 32-42.

86

Katharine Throssell, Child and Nation. A Study of Political Socialisation and Banal Nationalism in France and England, Berne, Peter Lang, 2015.

87

Yasmine Siblot, Faire valoir ses droits au quotidien. Les services publics dans les quartiers populaires, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 2006.

89

Alexis Spire, Faibles et puissants face à l’impôt, Paris, Liber, 2012.

89

Gérard Noiriel, “Un concept opératoire: ‘l'habitus national’ dans la sociologie de Norbert Elias”, Penser avec, penser contre. Itinéraire d’un historien, Paris, Belin, 2003, p. 171-188.

90

Gérard Noiriel, La Tyrannie du national. Le Droit d’asile en Europe, 1793-1993, Paris, Calmann-Lévy, 1991; Sarah Mazouz, Didier Fassin, “Qu’est-ce que devenir français ?”, Revue française de sociologie, vol. 48, no 4, 2007, p. 723‑750; ”Une célébration paradoxale. Les cérémonies de remise des décrets de naturalisation”, Genèses, n° 70, 2008, p. 88‑105.

91

Abdelmalek Sayad, “Les enfants illégitimes: 2e partie”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 26, 1979, p. 117-132.

92

Patrick Weil, Qu’est-ce qu’un Français ? Histoire de la nationalité française depuis la Révolution, Paris, Gallimard, 2005 (revised and expanded edition).

93

Bruce E. Cain, D. Roderick Kiewiet, Carole J. Uhlaner, “The Acquisition of Partisanship by Latinos and Asian Americans”, American Journal of Political Science, vol. 35, no 2, 1991, p. 390.

95

Christophe Broqua, Olivier Fillieule, Trajectoires d’engagement. AIDES et Act Up, Paris, Textuel, 2001.

96

Cécile Péchu, Droit Au Logement, genèse et sociologie d’une mobilisation, Paris, Dalloz, 2006.

96

Christophe Traïni, “Entre dégoût et indignation morale. Sociogenèse d’une pratique militante”, Revue française de science politique, vol 62, n° 4, 2012, p. 559-581.

97

Laura Stoker, M. Kent Jennings, “Life-Cycle Transitions and Political Participation: The Case of Marriage“, The American Political Science Review, vol. 89, no 2, 1995, p. 421.

98

Beanne Fahs, “Second Shifts and Political Awakenings: Divorce and the Political Socialization of Middle-Aged Women”, Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, vol. 47, no 3-4, 2007, p. 43-66.

100

Sophie Maurer, École, famille et politique. Socialisations politiques et apprentissages de la citoyenneté. Bilan des recherches en science politique, Dossier d’Étude CNAF, n° 15, 2000, p. 6.

100

Wilfried Lignier, Julie Pagis, “Quand les enfants parlent l'ordre social. Enquête sur les classements et jugements enfantins”, Politix, n° 99, 2012, p. 23-49; “Inimitiés enfantines. L'expression précoce des distances sociales”, Genèses, n° 96, 2014, p. 35-61; L'enfance de l'ordre. Comment les enfants perçoivent le monde social, Paris, Le Seuil, 2017. See also: A. Lareau, Unequal Childhoods. Class, Race, and Family life, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2011.

101

Florence Haegel, Sophie Duchesne, “La politisation des discussions, au croisement des logiques de spécialisation et de conflictualisation”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 54, n° 6, 2004, p. 877-909.

103

Camille Hamidi, La Société civile dans les cités. Engagement associatif et politisation dans des associations de quartier, Paris, Economica, 2010.

103

Organised by Yassin Boughaba, Alexandre Dafflon and Camille Masclet at the University of Lausanne.

104

That is to say “all the ordinary modalities through which awareness of one’s position and social belonging is formed, and all the dispositions aimed at enhancing and defending one’s interests – and this across all spheres of social life: at work, in family and home life, in residential spaces and practices of sociability, in the relationship to school, to institutions, in public life, etc.” (Yasmine Siblot, Faire valoir ses droits et se faire entendre. Rapports mobilisés à sa condition sociale en milieu populaire, Accreditation to supervise research dissertation, Paris IV, 2010, p. 36).

105

Annick Percheron, “La transmission des valeurs”, in F. de Singly (dir.), La Famille, l’état des savoirs, La Découverte, Paris, 1991, p. 183-193; “Histoire d’une recherche”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 44, n° 1, 1994, p. 100-126.

106

Annick Percheron, “La transmission des valeurs”, in F. de Singly (dir.), La Famille, l’état des savoirs, La Découverte, Paris, 1991, p. 191.

107

Daniel Gaxie, “Appréhensions du politique et mobilisations des expériences sociales”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 52, n° 2-3, 2002, p. 145-178.

109

Muriel Darmon, La Socialisation, Paris, Armand Colin, 2016.

110

Florence Haegel, Marie-Claire Lavabre, Destins ordinaires. Identité singulière et mémoire partagée, Paris, Presses de la FNSP, 2010.

110

In his book Tableaux de familles [Family portraits], Bernard Lahire puts forward a methodological and theoretical framework aimed at shedding light on the concrete modalities of the processes making up primary family socialisation. This involves observing social facts at an individual and family level, taking into account the effect of individuals’ social characteristics when analysing singular, or even atypical, cases, following the principle that transmission is not automatic, and giving importance to the material conditions, moments, and occasions of socialisation, etc. See B. Lahire, Tableaux de familles [1995], Paris, Le Seuil-Gallimard, 2012.

111

Manon Réguer-Petit, Les Belles-mères et la politique, Paris, L’Harmattan, 2012.

112

In the case of the transmission of “feminism” studied by Camille Masclet, we can see, for example, how transmission operates largely through control of language and recreational activities, rather than through the distribution of domestic tasks, as one might have imagined: “Le féminisme en héritage? Enfants de militantes de la deuxième vague”, Politix, n° 109, 2015, p. 45-68.

113

“More than family socialisation – which in this case appears relatively homogeneous among the siblings – their different trajectories through different spheres from childhood onwards, as well as their respective sex, affected and created variations in the opportunities for them to update and reinforce dispositions inherited in the family sphere”, Camille Masclet, “Le féminisme en héritage? Enfants de militantes de la deuxième vague”, Politix, n° 109, 2015, p. 45-68.

Bibliographie

Simone Abendschön (dir.), Growing into Politics: Contexts and Timing of Political Socialisation, Colchester, ECPR Press, 2013.

Catherine Achin, Lucie Bargel, Delphine Dulong, Éric Fassin, Sexes, genre et politique, Paris, Economica, 2007.

Catherine Achin, Delphine Naudier, “Trajectoires de femmes ‘ordinaires’ dans les années 1970”, Sociologie, vol. 1, no 1, 2010, p. 77-93.

Catherine Achin, Sandrine Lévêque, “La parité sous contrôle”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 204, 2014, p. 118-137.

Benedict R. Anderson, Imagined Communities Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism, London-New York, Verso, 1983.

Marco Antonsich, “The ‘Everyday’ of Banal Nationalism – Ordinary People’s Views on Italy and Italian”, Political Geography, 2015, p. 32-42.

Lucie Bargel, Jeunes socialistes / Jeunes UMP. Lieux et processus de socialisation politique, Paris, Dalloz, 2009.

Lucie Bargel, “Socialisation politique”, in Dictionnaire des mouvements sociaux, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 2009, p. 510-517.

Lucie Bargel, “Socialisation politique”, in Dictionnaire genre & science politique, Paris, Presses de Sciences Po, 2013, p. 468-480.

Willy Beauvallet, Sébastien Michon, “Professionalization and Socialization of the Members of the European Parliament”, French Politics, vol. 8, no 2, 2010, p. 145-165.

Michael Billig, Banal Nationalism, s.l., SAGE, 1995.

Jean-Luc Bodiguel, “La socialisation des hauts fonctionnaires. Les directeurs d’administration centrale”, in CURAPP (dir.), La Haute administration et la politique, Paris, PUF, 1986, p. 81-99.

Christophe Broqua, Olivier Fillieule, Trajectoires d’engagement. AIDES et Act Up, Paris, Textuel, 2001.

Nancy Burns, Kay Lehman Scholzman, Sidney Verba, Family Ties: Understanding the Intergenerational Transmission of Participation | Russell Sage Foundation, s.l., Russell Sage Foundation Working Paper Series, 2003.

Bruce E. Cain, D. Roderick Kiewiet, Carole J. Uhlaner, “The Acquisition of Partisanship by Latinos and Asian Americans”, American Journal of Political Science, vol. 35, no 2, 1991, p. 390-422.

Angus Campbell, Philip E. Converse, Waren E. Miller, Donald E. Stokes, The American Voter, Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1960.

Marie Cartier, Les Facteurs et leurs tournées. Un service public au quotidien, Paris, La Découverte, 2003.

Ioana Cîrstocea, “‘Soi-même comme un autre’: l’individu aux prises avec l’encadrement biographique communiste (Roumanie, 1960-1970)”, in C. Pennetier, B. Pudal (dir), Le Sujet communiste. Identités militantes et laboratoires du “moi”, Rennes, PUR, Rennes, 2014, p. 59-78.

Annie Collovald, Erik Neveu, “Le néo-polar. Du gauchisme politique au gauchisme littéraire”, Sociétés et représentations, n° 11, 2001, p. 77-93.

Raewyn W. Connell, “Why the ‘Political Socialization’ Paradigm Failed and What Should Replace It”, International Political Science Review / Revue internationale de science politique, vol. 8, no 3, 1987, p. 215-223.

Philip E. Converse, Georges Dupeux, “Politicization of the Electorate in France and the United States”, Public Opinion Quarterly, vol. 26, no 1, 1962, p. 1-23.

Guillaume Courty (dir.), Le Travail de collaboration avec les élus, Paris, Michel Houdiard Éditeur, 2005.

Élise Cruzel, “‘Passer à l’Attac’: éléments pour l’analyse d’un engagement altermondialiste”, Politix, n° 68, 2004, p. 135-163.

Grégory Daho, “La socialisation entre groupes professionnels de la politique étrangère”, Cultures & Conflits, no 98, 2015, p. 101-131.

Russel J. Dalton, “The Pathways of Parental Socialization”, American Politics Quarterly, vol. 10, n° 2, 1982, p. 139-157.

Muriel Darmon, La Socialisation, Paris, Armand Colin, 2016.

Yves Deloye, “Socialisation religieuse et comportement électoral en France. L’affaire des ‘catéchismes augmentées’ (19e-20e siècles)”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 52, no 2, 2002, p. 179-199.

Lucyna Derkacz, Socialisation politique au Parlement européen. L’exemple des eurodéputés polonais, Windhof, Promoculture, 2013.

Jan W. van Deth, Simone Abendschön, Meike Vollmar, “Children and Politics: An Empirical Reassessment of Early Political Socialization”, Political Psychology, vol. 32, no 1, 2011, p. 147-174.

Delphine Dulong, Frédérique Matonti, “Comment devenir un(e) professionnel(le) de la politique? L’apprentissage des rôles au Conseil régional d’Île-de-France”, Sociétés & Représentations, no 24, 2007, p. 251-267.

David Easton, Jack Dennis, Children in the Political System. Origins of Political Legitimacy, New York, McGraw-Hill Book Company, 1969.

Nathalie Ethuin, “De l'idéologisation de l'engagement communiste. Fragments d'une enquête sur les écoles du PCF (1970-1990)”, Politix, n° 63, 2003, p. 145-168.

Beanne Fahs, “Second Shifts and Political Awakenings: Divorce and the Political Socialization of Middle-Aged Women”, Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, vol. 47, no 3-4, 2007, p. 43-66.

Éric Fassin, Christine Guionnet (dir.), “Dossier ‘la parité en pratiques’”, Politix, no 60, 2002.

Olivier Fillieule, “Le désengagement d’organisations radicales”, Lien social et politiques, n° 68, 2012, p. 37-59.

Olivier Fillieule, “Postface. Travail, famille, politisation”, in I. Sainsaulieu, M. Surdez (dir.), Sens politiques du travail, Paris, Armand Colin, 2012.

Jon E. Fox, Cynthia Miller-Idriss, “Everyday nationhood”, Ethnicities, vol. 8, no 4, 2008, p. 536-563.

Julien Fretel, “Quand les catholiques vont au parti”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, n° 155, 2004, p. 76-89.

Daniel Gaxie, “Économie des partis et rétributions du militantisme”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 27, no 1, 1977, p. 123-154.

Daniel Gaxie, Le Cens caché. Inégalités culturelles et ségrégation politique, Paris, Le Seuil, 1978.

Daniel Gaxie, “Appréhensions du politique et mobilisations des expériences sociales”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 52, n° 2-3, 2002, p. 145-178.

Ernest Gellner, Nations and Nationalism, Ithaca-NY, Cornell University Press, 1983.

Didier Georgakakis (dir.), Le Champ de l’Eurocratie. Une sociologie politique du personnel de l’UE, Paris, Economica, 2012.

Didier Georgakakis, Marine de Lassalle, “Genèse et structure d’un capital institutionnel européen”, Actes de la recherche en sciences sociales, no 166-167, 2007, p. 38-53.

Philippe Gottraux, Cécile Péchu, “Le réalignement politique à droite d’un petit commerçant: complexité de l’analyse des ‘dispositions politiques’”, in I. Sainsaulieu, M. Surdez (dir.), Sens politiques du travail, Paris, Armand Colin, 2012.

Fred I. Greenstein, “The Benevolent Leader: Children’s Images of Political Authority”, The American Political Science Review, 1960, vol. 54, no 4, p. 934-943.

Florence Haegel, Sophie Duchesne, “La politisation des discussions, au croisement des logiques de spécialisation et de conflictualisation”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 54, n° 6, 2004, p. 877-909.

Florence Haegel, Marie-Claire Lavabre, Destins ordinaires. Identité singulière et mémoire partagée, Paris, Presses de la FNSP, 2010.

Camille Hamidi, La Société civile dans les cités. Engagement associatif et politisation dans des associations de quartier, Paris, Economica, 2010.

Robert D. Hess, David Easton, “The Child’s Changing Image of the President”, Public Opinion Quarterly, vol. 24, no 4, 1960, p. 632-644.

Robert D. Hess, Judith V. Torney, The Development of Political Attitudes in Children, Chicago, Aldine, 1969.

Herbert Hyman, Political Socialization. A Study in the Psychology of Political Behavior, New York, Free Press, 1959.

Olivier Ihl, “Socialisation et événements politiques”, Revue française de science politique, vol. 52, n° 2-3, 2002, p. 125-144.

Asmaa Jaber, “La socialisation politique enfantine dans des familles d’origine immigrée”, Recherches familiales, n° 12, 2015, p. 247-261.

Alban Jacquemart, “L’engagement féministe des hommes, entre contestation et reproduction du genre”, Cahiers du Genre, no 55, 2013, p. 49-63.

M. Kent Jennings, Richard G. Niemi, “The Transmission of Political Values from Parent to Child”, American Political Science Review, vol. 62, no 1, 1968, p. 169–184.