Constitutionalism developed as a worldwide political movement over the course of the nineteenth century, making its impact felt in the Middle East, particularly in the Ottoman Empire1. In purely legalistic terms, it promoted a system of regulations in which political power was both legitimised and limited by the law. It was thus closely correlated to attempts to establish an administration based on rational and legal principles which marked the transformation of the State in the Middle East. Constitutionalism may however be taken in a broader sense, in which it is the main vehicle for redefining politics in line with the principles of popular sovereignty. It is thus linked to the emergence of democratic institutions and ideas such as citizenship, political representation, and the separation of powers – and is related to the Republican and liberal tendencies within Western political philosophy. Although it was a contradictory and incomplete movement, it nevertheless fed into the Persian and Ottoman constitutional revolutions (1906 and 1908 respectively), giving rise to a genuinely democratic experiment in most of the Middle East, thereby bequeathing a political legacy of capital importance to the twentieth century – a legacy which has undergone a certain political resurgence since the events of the “Arab Spring”.

Past studies of constitutionalism have looked at what it brought to the process of State centralisation and the development of modern administrations, or else its contribution to the debate about the compatibility between Islam and democratic values. But very little has been said about how it relates to intellectual history, and its political significance for the Middle East has arguably remained undervalued2. This text seeks to set out a new interpretation of constitutionalism and its impact on the Middle East by concentrating on its evolution from the Ottoman Empire.

Boatmen in front of the New Mosque in Istanbul, 1888.

The Sultans of the Ottoman dynasty.

Pre-modern ideas about consultation and the oversight of power

The idea that the power of the sovereign was subject to laws and to some degree of oversight existed in Islamic empires well ahead of the emergence of modern constitutionalism. Islam curbed the exercise of power, which had to conform to sharia – even though the possibility of interpreting divine law provided the sovereign with fairly extensive room for manoeuvre. The Islamic tradition also included the principle of “consultation”, referred to in Arabic by the terms Shura and Mashwara, and in Turkish by the words Şûra and Meşveret. The key textual references were to passages in the Koran (III, 153/159 ; XLII, 36/38), corroborated by a large number of hadiths (observations attributed to the Prophet Muhammad), which enjoined the caliph to seek the opinion of the community of faithful before taking decisions. Electoral and consultative practices in the early days of Islam were also cited to emphasise the sovereign’s duty to consult the community3.

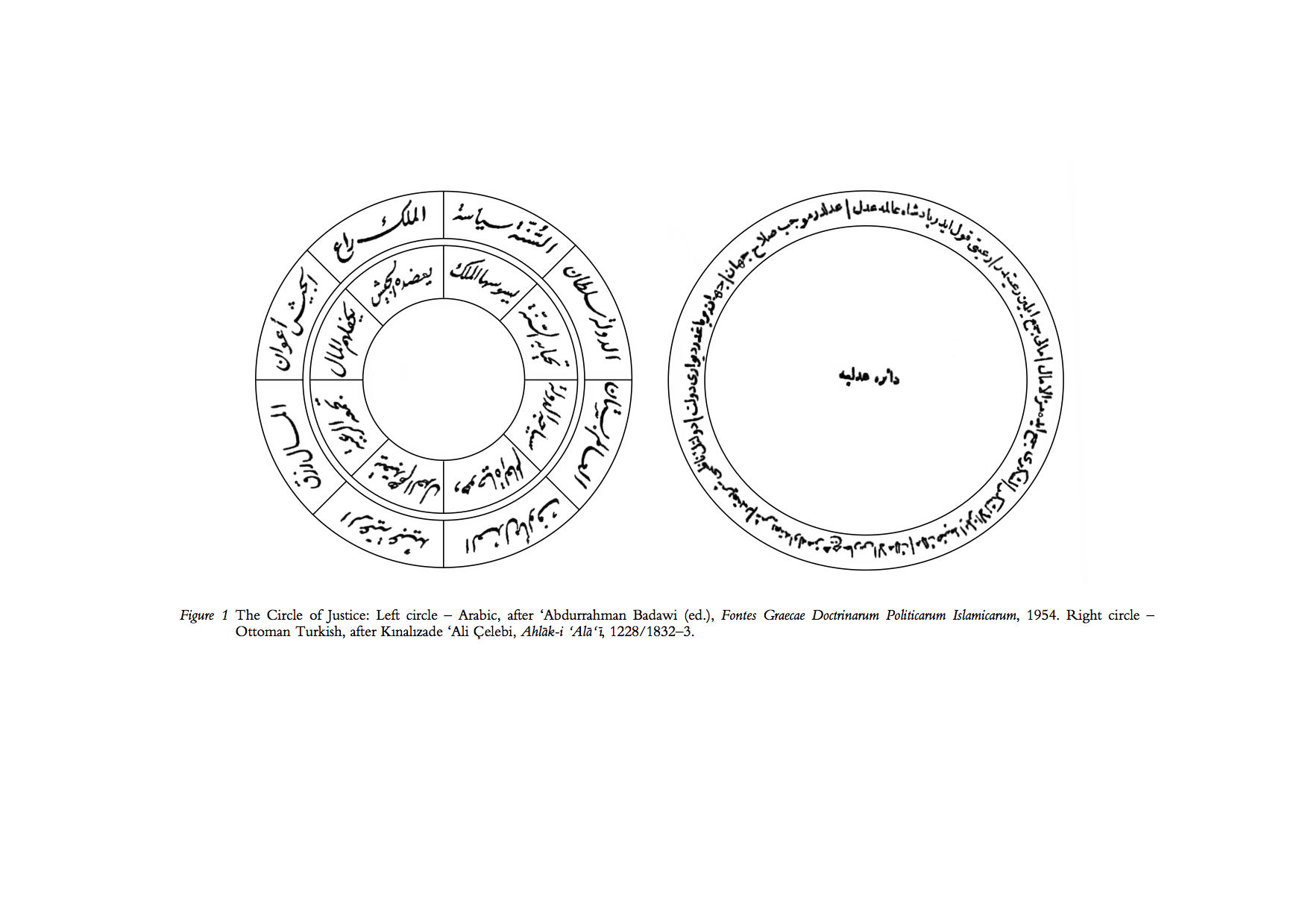

Nevertheless, and contrary to what fundamentalist Muslims and Orientalist observers seem to conjointly suggest today, religion has never been the sole basis for political and social life in Muslim countries. The main political legitimacy of Islamic states was the ideal of justice, as expressed in the “Circle of Justice”. This aphorism of Greco-Persian origin proposed an imperial order corresponding to the cyclical nature of agrarian society and the economy. Imperial power relies on armed force, enabling the sovereign both to carry out conquests and ensure order and justice. Justice primarily entails the well-being of his subjects, particularly of peasants, who drive economic production and guarantee the prosperity of the State. That provides for a strong army which gives the sovereign the tools he needs to secure the rule of justice. The Sultan is thus obliged to listen to his subjects to protect them from abuses and from all forms of arbitrary power4. This virtuous circle of justice was regularly put forward by writers to describe the ideal of a just reign to which the Sultan was to be held, and to proscribe the despotic wielding of power.

Abdurrahman Badawi (ed.), Fontes Graecae Doctrinarum Politicarum Islamicarum, 1954. Kınalızade Ali Çelebi, Ahlâk-i Âlâî, 1228/1832–3

Circle of Justice, Ibn Khaldun, al-Muqaddimah, 15th c. MS, British Library Add. 9574, s. 29v.

This concept of “justice” stemming from Middle Eastern philosophy left a strong mark on political thought in the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman State, which emerged as a power in north-western Anatolia in the early fourteenth century, rapidly expanded its territory in the Balkans and Middle East over the course of the two following centuries, thereby becoming an empire. It was heir to the long imperial tradition in Islam, which it took up within its political philosophy. The image of “Oriental despotism” elaborated in Enlightenment philosophy was far from corresponding to the actual structure of Ottoman power. In principle the Circle of Justice as a form of legitimisation for political authority was accompanied by a quest for some degree of legality, in reference to a glorified imperial period of the past, sometimes identified as the reign of Sultan Suleiman (1520-1566) or that of Alexander the Great. Religious scholars and bureaucrats championed a legalistic conception as of the seventeenth century, thereby operating a certain distinction between the State and the sovereign. The power of the sovereign was also counterbalanced by the military Janissary corps. Although they lost some of their military clout as of the seventeenth century, they were able to exert control over imperial power, notably by voicing the discontent of urban populations about imperial measures viewed as unjust, and by calling on the Sultan to respect “the ancient law” so as to ensure the rule of justice. Their interventions could go as far as deposing a Sultan accused of having failed to abide correctly by the law5.

In addition to this, there was indeed a form of consultation within various administrative institutions of the Ottoman Empire, exerted via petitions, imperial surveys, and “consultative councils” (Meclis-i Şûra/Meşveret). These councils – composed of high-ranking statesmen, and sometimes representatives from professional corporations or religious communities – held sporadic assemblies during which a consensus was sought on decisions to be taken. There was a marked proliferation in these councils over the course of the eighteenth century, at a time when the Ottoman Empire found itself in an increasingly precarious military and economic situation. They thus clearly expressed a sense of crisis6.

All in all, pre-nineteenth-century political philosophy in the Middle East visibly did enquire into the oversight of power, the legality of imperial authority, and the merits of consultative practices. These were a major inspiration behind the elaboration of constitutionalist principles. In the first half of the nineteenth century, for instance, considerable insistence started to be placed on “justice”. In parallel to this, the Islamic principles of consultation gave rise to a whole body of works asserting the compatibility between Islam and modern political values, drawing on fairly free reinterpretations of ancient principles meant to support a new and radically different way of conceiving of politics.

Yet the principle of Meşveret had never included the possibility of consulting the people, referring only to high-ranking dignitaries. Any broader consultative practice was on the contrary denounced as inducing political paralysis, and consequently disorder, thereby interrupting the Circle of Justice. The idea of justice, in its classical political conception, tended to be linked to the absolute exercise of power, for only a strong sovereign was deemed able to ensure the protection of the weak. No treaty ever called into question the Sultan’s prerogative to legislate. Consultation with qualified political figures was presented as an affirmation of sovereign law in a hierarchical society stratified into immutable categories. Equally, the ideal of justice and ancient law represented retrograde points of reference, only acquiring meaning within an immobile and cyclical conception of politics and time.

It was thus primarily disruptions to this pre-modern conception that led to constitutionalism emerging as a political movement in the Middle East over the course of the nineteenth century, mainly inspired by foreign ideas and associated with new forms of western influence.

The economic and military ascendancy of Europe of the Industrial Revolution and the restructuring of the world under Western domination decisively altered the balance of power between Europe and the Ottoman Empire. The Ottoman elite were quick to note the superiority of the West, leading in turn to the question of why the Empire was weak. Hence the desire to alter the internal organisation of State so as to conduct deep reform of Ottoman society and bring it closer in line with the new ideal of “civilisation”7. This transformation was supported by the European powers, first among which were France and Britain, who reckoned that the existence of a centralised State and unified market running from the Balkans to the Middle East and Northern Africa would further their economic expansion in these regions. Ottoman reform was thus closely bound up with the integration of the Empire into the capitalist economy and the process of global uniformisation in accordance with Western norms.

The Tanzimat and the reconfiguration of the Ottoman political sphere

New forms of political mobilisation sprang up in several Ottoman provinces, before spreading to the central State, and were often accompanied by early references to constitutionalism. In 1797 the Greek writer Rigas Velestinlis-Feraios, taking his cue from the ideas of the French Revolution, suggested forming a constitutional federated State taking in the Balkans and Anatolia. In the 1820s the Greek War of Independence was conducted in the name of the constitutionalist ideal, thus becoming a reference for international liberalism. The first organic law of the Ottoman Empire, called the “Turkish Constitution” and relating to the organisation of the autonomous Principality of Serbia, was promulgated by imperial decree in 1838.

The Greek crisis in particular was a decisive event in pushing the central State to initiate a process of transformation. This started in the 1820s during the reign of Mahmud II (1808-1839), and was expanded after his death in the period known as the Tanzimat – literally the “reorganisation”. The reform policy asserted the sovereignty of the central State in an empire which had been decentralising over the course of the two previous centuries, to such an extent that the writ of the capital often existed only on paper, with local potentates exercising their autonomy. The purpose of the reform movement was to set up a new and direct relationship between the State and its subjects, and to establish a rational-legal order based on a programme of centralisation and the expansion of State power by adopting western norms.

This is the context within which the idea of giving written form to administrative practices and codifying the power of the State first emerged. One first such attempt dates from the beginning of the reign of Mahmud II, when an assembly of central administrators and provincial notables agreed on a document setting limits to the power of the Sultan in exchange for recognising his authority in the Ottoman provinces. This document, known as the Sened-i İttifak (Charter of Alliance), is considered in the legalist school as the first constitutional text in Turkish history. Like the Magna Carta, to which it is often compared, the Sened-i İttifak was not followed by any effects. Instead its importance only became apparent retrospectively, as symptomatic of a new political awareness distinguishing between the State and the sultan, and putting forward a new framework for the exercise of power8.

The wish to expand the reform beyond the upper echelons of the bureaucracy and to give it lasting form led to the emergence of certain pragmatic considerations which have become the pillars of constitutionalism. The first of these was the oversight of power. The intention was to redefine the State’s spheres of authority within a shifting political landscape, with an attendant concern for developing and rationalising administrative practices, which ultimately laid down the bases of the idea of a division of powers. The second pillar, integrating the people within the overall reform project, was deemed necessary so as to affirm the authority of the State in the various regions of the Empire, and at different layers of society, thereby seeking to redefine political relations in the long run.

Initially, however, constitutionalism was primarily used as an instrument to other ends. Following on from the economic liberalisation ushered in by the 1838 Anglo-Ottoman trade treaty, the new class of high-ranking westernised bureaucrats pushed for an official declaration reformulating the relationship between the Sultan and his subjects whilst according greater autonomy to the upper echelons of the bureaucracy. In November 1839 the imperial Edict of Gülhane was proclaimed. This introduced a series of administrative reforms, relating inter alia to tax collection and military service. It referred directly to the status of the Ottomans, and guaranteed life and dignity to all subjects. The edict, though couched in traditional political language, is once again indicative of the significance of the pre-modern idea of justice, proclaiming a new “just” rule bringing together the “community of the faithful”9. But there was something new about this document, for it operated within capitalist parameters, leading to a clean break with the Ottoman tradition.

Ottoman Sultan Abdülmecid (1839-1861).

The main point of reference for discussion of justice henceforth became the idea of civilisation rather than that of Islam. For the State elite, Europe and the Empire alike subscribed to this new ideal turned resolutely towards the future. Equally, the firman established for the first time the right to property for all Ottomans. Furthermore, these new elements were confirmed by the ceremony held for the proclamation of the edict, during which the new sultan, Abdülmecid (1839-1861), publicly undertook to respect his principles. The sultan thus no longer transpired as a sovereign by the grace of God and protector of his subjects’ well-being, but as a sovereign bound to respect the rights of the Ottomans. In 1856 the second major document of the Tanzimat, the “Imperial Reform Firman”, set out the reform principle. This was partly a concession to the great powers who had supported the Ottoman Empire during the Crimean War against Russia (1853-1856), as well as reflecting the supposed integration of the Empire into the “European concert” governed by liberal economic and political ideals. It set out the idea of equality between Muslim and non-Muslim Ottomans which had already been sketched out in the previous edict. All male Ottomans were declared equal before the law, in what was a seismic shift in the Muslim world10. Unlike the 1839 edict, the imperial firman did not use the language of Islam, indicating the rate at which traditional political ideas were becoming marginalised.

The reform policy, which had initially focused on the central administration of State, now started to affect the population more directly with the implementation of measures announced in the 1839 and 1856 edicts. These included the introduction of direct taxation, the launching of public schooling, the introduction of military service, and a series of judicial reforms (strongly influenced by the French model) seeking to establish a uniform and integrated legal system based on private property and the equality of all male Ottomans. Thus the 1856 firman defined civic freedoms and modern citizenship in the Ottoman territories. The setting up of representative provincial councils – intended to represent the population and composed of members elected by notables – also dates from this period.

Yet these changes were clearly not effected to introduce democratic practices or institutions11. They were rather an attempt by the new class of high-ranking bureaucrats to affirm their political power over the palace, whilst accommodating the wishes of the European powers. But despite this, the principle of the oversight of power is one of the axioms of the Ottoman transformation. Equally, there was a gradual redefinition of what it was to be Ottoman, who went from being subjects to being citizens, stemming from the idea that the people needed to be integrated within the reform process, and leading to the principle of political representation.

Prior even to the first of the Tanzimat edicts in 1839, a new idea of politics had started to take hold in the Middle East. Positive references to the parliamentary practices of European countries circulated in the Ottoman Empire as early as the 1820s, in accounts that were mostly written by travellers and diplomats. They attributed the strength of the West to the fact that its representative practices integrated the energy of the people into State affairs. These writings thus suggested that the relationship between the State and the people be reconsidered. The Egyptian writer Rifa’a al-Tahtawi (1801-1873) provided the first detailed description of parliamentarianism in an account of his trip to Paris in 1834. At the same period the Ottoman diplomat Sadık Rifat (1800-1858) wrote a series of memoranda which show that new political ideas were beginning to take hold in the Empire.

Rifat, in seeming reference to constitutionalist debates in Europe during the 1830s, though without any real show of liberal inspiration, emphasised the need for Ottoman reform to be effective, arguing that the prosperity of the people and their integration into the transformation project would give stability to the policy of change. Nevertheless, he introduced several new concepts into Ottoman political discourse, for he took the Ottomans to be “citizens”, supposed the existence of a “nation”, and referred to the “people”, “freedom”, and “civic rights”. In his writings the distinction was no longer solely between the sultan and the State, but also between the State and the people. This ultimately led to a new idea of politics, with the people being taken as the object of political endeavour. Whilst the State and people (or nation) were not yet presented as having potentially divergent interests, the autonomy of the people and the nation was asserted. For Rifat, not only did the people and the nation exist independently of the State, but the State existed to serve the people. To his mind the secret of a strong State resided specifically in the concordance between the State and its citizens. European countries were said to have managed to realise such a fusion, and it was suggested that the Ottoman State now needed to carry out the same mission in order to catch up12.

The ideas expressed by Rifat did not yet amount to a coherent political theory. Nevertheless his writings show that the ideological characteristics of Ottoman constitutionalism started to take shape during the 1830s. For years these did not extend beyond the upper echelons of State. But these new political ideas were able to spread thanks to the redefinition of the status of Ottomans by the Tanzimat edicts and the flourishing modern public sphere which expanded the potential for communication. The Tanzimat edicts, contrary to the intention of their authors, gave rise to a new political language based on equality, freedom, and civic rights to develop, which was then taken up by various actors. This language paved the way to new political demands. And so there arose conflicting interpretations of the meaning of the Tanzimat, opposing a purely administrative interpretation of the reform programme to one which defined it as a global political process of emancipation13.

The Young Ottomans, the First Constitutional Period, and the case of Egypt

Experimentation with constitutional ideas at the administrative level continued over the course of the 1860s, combining a desire to establish a rational-legal order and the political demands of the emerging elite. In 1861 the autonomous province of Tunisia passed an organic law, often presented as the first constitution in the Muslim world. In fact it only set up a sort of national council to counterbalance the power of the local sovereign, without referring to the principle of political representation. Within the Empire, non-Muslim religious communities adopted internal regulations in accordance with their autonomous status guaranteed by Ottoman law (in 1862 for Greeks, 1863 for Armenians, and 1865 for Jews), which were named “constitutions”, echoing the political tendencies of the era. They provided the new secular elites with a means of asserting their authority over traditional groups. The Armenian constitution in particular acted as a catalyst for constitutional debate at the Ottoman imperial level.

Above all, it was with the emergence of public opinion as a new actor in the Ottoman political realm that constitutionalism went from being an administrative measure to a political movement. The launch of the first private newspapers in the 1860s turned the press into a realm for intense political debate, to such an extent that the government introduced restrictive regulations. At the end of the decade these changes led to the emergence of the Young Ottomans, the first constitutionalist movement in the Middle East, who were immediately persecuted by the State. Their newspapers addressed the literate class and used a political language based on freedom and fatherland, in conjunction with criticism of the government. Their stance led to the idea of a constitution taking on a normative, ideological meaning, emerging as a political force invoked in the name of modern citizenship.

What had started out for constitutionalism as pragmatic considerations – the oversight of power and integration of the people – became political principles. For the Young Ottomans the weakness of the Empire and its inferiority to the great powers were attributable wholly to the poor management of the country by a non-representative government, whilst the arbitrary exercise of power only continued to exist due to the self-interested policies pursued by European countries. The fusion between the State and citizens via political representation and the effective oversight of State power were, to their minds, the preconditions for Ottoman reform. This yoking together of general political principles with criticism of the current situation imbued the idea of a constitution with a utopian dimension. It henceforth held out the promise of a renaissance of the Ottoman Empire as a strong, sovereign country protected from European interference.

Thus the idea of a constitution was presented both as a means of Westernisation and as a criticism of the way Europe exerted imperialist domination over the Middle East. From this perspective constitutionalism was apprehended by the Young Ottomans not as an idea imported from the West but as a value complying with Islamic tradition. Indeed, they were the first to put forward an Islamic interpretation of constitutionalism, emphasising how Islamic principles were in agreement with this Western political philosophy. This interpretation was taken up and expanded by various Muslim reformists over the following years, such as Jamal ad-Din al-Afghani (1839-1897) and Muhammad Abduh (1849-1905). Like the Young Ottomans, they presented Islam as a religion that was open to progress, contrary to Western visions that described Islam as backward and incapable of change (along consequently with Muslim societies). The abundant literature on how Islam and democracy were compatible had its starting point in the interventions of these intellectuals during the 1860s and 1870s.

Constitutional ideas became more popular over the course of the 1870s when the Ottoman Empire started to be rocked by economic, financial, and political crises. In 1875 the Ottoman State had to declare bankruptcy, and the following year two sultans were deposed before Abdulhamid II (1876-1909) was enthroned. In the realm of diplomacy, Russia threatened to declare war, taking the protection of Christians in the Balkans as its pretext. On 23 December 1876 the Sultan issued the Ottoman Constitution by imperial decree. The surprise declaration sought primarily to circumvent scheming by the great powers, who had gathered in Istanbul to find a way out of the diplomatic conflict. For the Empire, a constitution offered a way of presenting itself as a civilised power in comparison to a backward, despotic Russia14. But the Ottoman Constitution cannot be thought of simply as a manoeuvre, for it also reflected changes in political ideas that were taking place within Ottoman society.

The Ottoman Constitution in Bulgarian.

This constitution set up the first parliamentary regime outside the Americas and Europe (leaving the complex history of the Republic of Liberia aside). It guaranteed Ottomans fundamental rights, endorsed the principle of political representation, and granted legislative power to parliament. Historians tend to accuse it of lacking “maturity” in the way it asserted popular sovereignty, in particular because it ascribed sacred status to the sultan and granted him significant executive powers. But such criticisms overlook that the Ottomans were following what was at the time the most widely copied and adapted example of a constitution, namely the 1831 Belgium constitution whose purpose (inspired by the 1814 French Constitutional Charter) was clearly to assert the legitimacy of the sovereign, and to reach an accommodation between a monarchic system and the parliamentary principle15. For that matter no sooner had the Ottoman parliament been set up than events showed that the Constitution led to a crucial change in ways of thinking about politics.

The first Ottoman parliament, composed of a Chamber of Deputies and a Senate, convened on 19 March 187716. It immediately demonstrated that it was not going to content itself with a merely consultative role, and to everyone’s surprise displayed a combative turn of mind against the government17. The parliamentary principle appeared to be firmly established and fed into the opposition being voiced in the public domain. The press became increasingly critical of power, to such an extent that this period has been presented as a “Young Turk Republic”18. Just a few weeks after the opening of parliament the Empire went to war against Russia, with disastrous effects. The existence of an opposition became very problematic for the government. Sultan Abdulhamid II – despite having promised on acceding to the throne to promulgate the constitution and to respect parliamentary order – suspended the Ottoman parliament on 14 February 1878, thereby putting an end to the Empire’s first experiment with democracy. This brief experience nevertheless bequeathed a significant political heritage, for the principles of the constitution were henceforth regarded as major points of political reference.

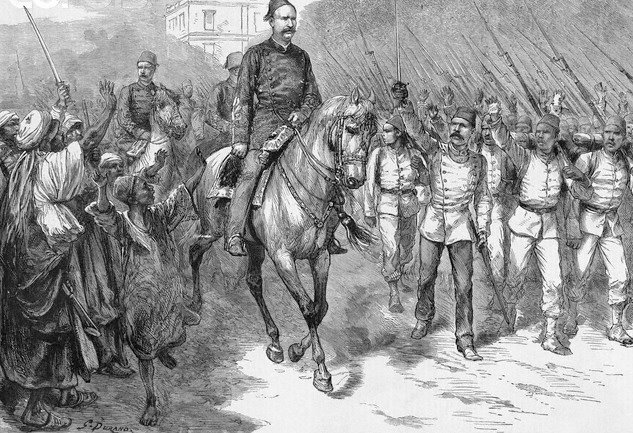

The Urabi Revolt.

The next constitutional episode took place in Egypt where constitutionalism emerged as a popular movement for the first time. The introduction of financial supervision over the Egyptian State by the European powers in 1876 fed into popular discontent, triggering a political crisis. Colonel Ahmed Urabi became the representative of this discontent, channelling it in a constitutionalist direction. In 1881 he assumed leadership of a revolt and imposed a new political system on Khedive Tawfik19. On 7 February 1882, the newly elected Egyptian assembly passed an organic law. This was of great symbolic value, for it was the first time a constitution had been declared by a representative assembly rather than being promulgated by a sovereign20.

Opening of the Ottoman Parliament, 1877.

This constitution turned out however to be even more short-lived than the Ottoman Constitution. France and Great Britain, judging their interests to be under threat, condemned the constitutional regime. In July 1882 they took action, bombarding Alexandria. Urabi established a government in Cairo, but in September his peasant army had to retreat in front of British forces. An alliance between the local landowning class and the great powers put an end to the first popular constitutional experiment in the Middle East. The power of the elite surrounding the khedive was restored, and Egypt formally declared to be under British occupation. The Egyptian example thus established a precedent which subsequently marked the twentieth-century history of constitutionalism in the Middle East. Western powers, in order to protect their interests, were ready to enter into alliances with anti-democratic local elites and to act against constitutional movements.

The Hamidian regime, the Young Turks, and the Iranian Revolution

The experience in Egypt probably confirmed Abdulhamid II’s decision to suspend the Ottoman constitution indefinitely. The need to establish a new order in the wake of the Russo-Turkish war of 1877-78 provided the Sultan with the opening he needed to impose autocratic rule. At the beginning of his reign he was obliged to commission books to legitimise the return to absolute rule and present himself as a “just” monarch, being the sole authority able to guarantee the coherence and sovereignty of the Empire21. Over the course of the following years he set up a government excluding any form of representative body. His regime was marked by surveillance, the exile of his opponents, and the stifling of all political debate. But the constitutionalist idea shifted and became reformulated within an alternative public domain when the Young Turks emerged in the 1890s, going on to become a mass constitutionalist movement.

This movement made its breakthrough during the Armenian crisis of 1895 when the great powers seemed fixed on putting an end to the independence of the Ottoman Empire. Henceforth the Young Turks embodied opposition to the Hamidian regime. Many of them were exiles, mainly in Paris, and to argue for their positions they set up clandestine journals which were distributed throughout Ottoman territory as well as in the Balkans and Caucasia. Political debate was largely banned within the Empire, meaning these journals became the main forum for constitutional ideas. The Young Turks systematised the constitutionalist tendencies that had been coming to the fore since the first half of the nineteenth century, and constitutionalism thus emerged as the driving force behind a powerful political cause.

The Young Turks formed an extremely disparate movement, based around three core beliefs: an ideology of progress imbued with scientism, according to which the future of society lay with scientific order; virulent opposition to Sultan Abdülhamid, labelled the main culprit for the backwardness of the Ottoman Empire; and a call for the establishment of a constitutional system, presented as the remedy for the many ills afflicting the Empire. This combination provided an effective means for mobilising political support. The Young Turks attacked the Sultan as a figure from a bygone era despising the will of the nation, and whose reign failed to comply with the needs of modern times, plunging the Empire into obscurantism and rendering it inferior to the West. The charge of despotism referred not solely to the power wielded by a selfish individual, but to an entire system which corrupted society and prevented the Ottomans from recognising their true interests. The return to a parliamentary regime would, in contrast, guarantee prosperity, independence from the great powers, and fraternity between all the peoples in the Empire. The constitution was thus a revolutionary project, alone able to fuse the government and the people and create a civilised society.

The Young Turks also embodied a dimension of constitutionalism which had existed in latent form in early projects without having been clearly spelt out--namely the need to establish an adequate political culture to accompany a constitutional political regime. Whereas their predecessors had regarded the declaration of a constitution as somehow automatically generating political effects, the Young Turks took due note of the failure of past constitutional experiments and of the complexity of modern society. They reckoned that a new political structure would only be viable if rooted in a culture of citizenship supporting the parliamentary architecture. In this context they displayed an obsession with education they had inherited from the pedagogical spirit of the Enlightenment, and revealed a desire to channel the scope for emancipation that constitutionalism held out. They hence devised a concept of citizenship based not only on the rights of Ottomans, but also on their duties, defined as the responsibility each had towards the fatherland and universal civilisation.

Unlike the Young Ottomans, the Young Turks did not try to put forward a synthesis between Western constitutional theory and the Islamic tradition. They just noted that there was no opposition between the constitution and Islamic law. Thus debate about Islamic constitutionalism was not taken up in Ottoman and Turkish political culture subsequent to the Young Ottomans. The attempt to give an Islamic dimension to constitutionalism was carried forward primarily by Arab and Iranian intellectuals.

A postcard celebrating the 1908 Young Turk revolution, showing “liberty”, and “fraternity” between the different nations of the Ottoman Empire.

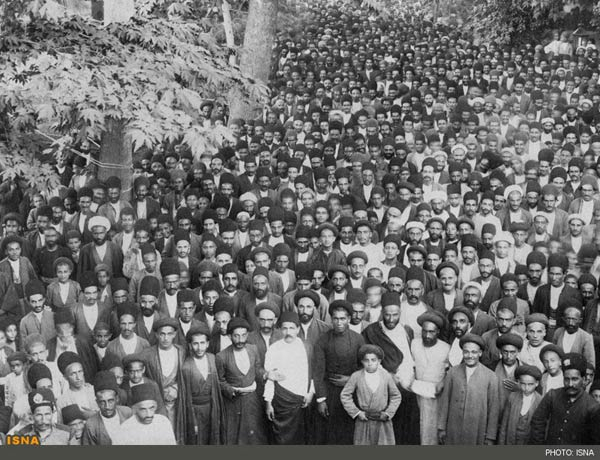

This tradition was very clearly at work in the Iranian constitutionalism of 1906 to 1911. One of the particularities of this constitutionalist movement was that it was based on the extensive involvement of clerics. The Iranian Revolution took place within a worldwide cycle of revolutions ushered in by the Russian Revolution of 1905, a cycle which had affected over a quarter of the world’s population by the outbreak of the First World War (with revolutions in Russia in 1905, Iran in 1906, the Ottoman Empire in 1908, Portugal in 1910, and then Mexico and China in 1911)22. The constitution – declared after a mass movement and approved by an assembly of elected delegates in December 1906 – sought to adhere to the principles of sharia, thereby reflecting the clear influence of clerics. However, this Islamic approach to constitutionalism needs to be distinguished from the fundamentalist interpretations which subsequently developed over the course of the twentieth century. In 1906 divine law was to place limits on the constitution, but it did not provide a basis for legislation23.

Teheran, summer 1907.

Source: http://www.payvand.com/news/13/aug/1034.html

The backing of the clerics was nevertheless ambiguous. They largely withdrew their support when the constitutional regime failed to deliver the reckoned order. Parliament was taken by force in June 1908 on the order of the Shah and with the agreement of Russia and Great Britain (who had divided Iran into spheres of influence). Iran entered a period of disorder that split society and weakened the country, reducing the constitution to a document with little political effect, even though it remained in force up until the Islamic Revolution of 1979.

The 1908 Young Turk Revolution and the Second Constitutional Period

As the Iranian parliamentary buildings were being attacked in Teheran, the constitutional revolution was swinging into motion in the Ottoman Empire. A military revolt launched by the Young Turks in Macedonia gathered impetus and became a genuine revolution. On 23 July the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP), the largest Young Turk organisation, placing their faith in the protest movement they had unleashed, declared the 1876 Ottoman Constitution to be reinstated.

This sent a shockwave across the Balkans and the Middle East24. The slogan of the French Revolution – “Liberty, Equality, Fraternity” – resonated on all fronts, and it seemed a new society was about to see the light of day. General elections were held in the autumn. On 17 December 1908 a crowd of 300,000 people gathered to attend the opening of the Ottoman parliament. The Chamber was quick to take up the pugnacious attitude of the First Constitutional Period, and displayed great political confidence. It exerted powers in fields exceeding the restrictive framework imposed by the constitution, making and unmaking cabinets, and assuming full legislative power. Popular sovereignty as represented by the Ottoman Chamber underwent a political shift, becoming the source of legitimacy for Ottoman politics. However this Second Constitutional Period was to have a troubled history.

“Liberty, Equality, Fraternity”: Postcard and tissue.

The first ordeal came in April 1909 when a revolt broke out in Istanbul, triggered by clerics and those disappointed in the revolution. Ethnic tensions resurfaced in the ensuing chaos, and several tens of thousands of Armenians were killed in the town of Adana. The army had to step in to suppress the counter-revolution and re-establish constitutional order. The sultan was identified as the culprit for the revolt, and the Senate and the Chamber, sitting together as a National Assembly, opted to depose him. Abdulhamid II was not the first Ottoman Sultan to be deposed, but he was the first to fall from power in the name of the nation. In a way it was the peak of the revolution, for popular sovereignty as represented by parliament was affirmed against the monarchic principle, consequently reinforcing the constitutional system.

The enormous hope placed in the constitution was nevertheless undermined by this counter-revolutionary episode. In fact it initiated various traits which subsequently marked the history of the Ottoman parliament, and went on to have a significant and more general impact on constitutionalism in the Middle East over the course of the twentieth century.

First, the Adana massacres gave rise to doubts about parliament’s capacity to establish itself as a transcommunal political body and to meet the needs and aspirations of all citizens. The various communities in the Empire continued to work within the constitutionalist framework, but with an increasingly pronounced tendency to set up parallel political forums, whilst the State progressively went down the path of an ethno-nationalist policy defining Muslims – and in particular Turks – as the true pillars of the Empire, to the detriment of other Ottoman groups25. Second, the political elite became increasingly distrustful of the people, doubting their attachment to the parliamentary principle. It was the army who had put down the counter-revolt, not the population itself. This appreciation led to an increasingly authoritarian turn in Ottoman constitutional thought. Third, and for the same reason, the army became a full-fledged political actor, elevated to the status of the guardian of the parliamentary system, thereby creating a virtually organic link between the army and parliament, in which the latter could be placed under military supervision.

These various trends posed complex challenges to the liberal current within constitutionalism. With the progressive destabilisation of the political order in the wake of the Italo-Turkish War (1911-1912), the two Balkan Wars (1912-13), and finally the First World War, these challenges turned out to be insurmountable, and the authoritarian tendencies won out. In January 1913 a military coup led by the CUP unseated the Chamber. It re-formed in the summer of 1914, but the parliamentary session only lasted a few months due to the war. The CUP thus established a dictatorial regime operating largely above any parliamentary oversight, even though its institutions were not abolished.

The Ottoman constitutional experiment thus bequeathed a contradictory legacy to the Middle East. Apart from the fact that it demonstrated that constitutionalism was an incomplete and fragile project, exposed to internal and external threats, it generated a new form of authoritarianism not unrelated to the constitutive paradoxes of parliamentary democracy since the French Revolution. The CUP did not in fact develop its authoritarian regime by denying the principles of constitutionalism and popular sovereignty. Instead, it reckoned that in a crisis requiring authoritarian policies, it best represented national interests. This example went on to establish a model for a modern yet dictatorial political regime that has been of great significance in the history of constitutionalism in the Middle East.

Afterword. The Ottoman legacy of constitutionalism to the Middle East

The history of constitutionalism after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire was equally troubled. The French and British occupation of most of the Middle East and the emergence of nation states shifted the constitutional struggle in new directions. It had to grapple with the divergent agendas of various forces: religious and monarchic groups who at best viewed constitutionalism as a means to an end, new nationalist groups trying to entrench their position as an elite, and imperialist powers ready to turn against parliamentary regimes whose policies ran counter to their interests. All of these forces could unite to combat the socialist movement, which endeavoured to take up the constitutional struggle and carry its utopian dimension to new levels.

Apart from the case of Israel, it is in the Republic of Turkey that constitutionalism has existed with the greatest degree of continuity. After the First World War Turkey was the only independent State of the former Ottoman Empire. Even though the country went through a period of single-party rule lasting until 1950, and has experienced countless political crises marked in particular by army interference – which on three occasions (in 1960, 1971, and 1980) invoked its role as guardian of the constitution it had inherited from the Ottoman experiment – the parliamentary system and democratic practices, though far from exemplary, have enjoyed a degree of stability that is unique in the region. Up to the present day, the constitutionalist ideal is regularly put forward to demand that the rule of law and civil liberties of all citizens be respected, as part of a quest for a more democratic society, in opposition to an increasingly pronounced populist authoritarianism that attempts to push back on basic civic rights.

In Iran, the Civil War and intervention by foreign powers during the initial Constitutional Period left a more fragile political heritage. During most of the twentieth century the Iranian parliament was a puppet, and power was concentrated in the hands of the Shahs with the backing of Western powers. This was one of the main reasons for the rise of Islamism, which presented herself as an alternative political movement to the existing constitutionalism. The constitution adopted in the wake of the 1979 Islamic Revolution was directly inspired by the constitution of the French Fifth Republic, in that it established an authoritarian presidential republic26. The Iranian constitution is however unique in according predominance to religious over political institutions, thereby establishing a theocratic system.

Constitutionalism in the Arab countries has had a harder time. The policies of France and Britain who ruled the region after having carved it up into mandates were set to ethnicise the populations and to win over local traditionalist elites, and made it difficult to resurrect the liberal heritage of constitutionalism once Arab states won their independence. This political framework gave rise to the authoritarian regimes that tend to be associated with contemporary Arab political culture. They present themselves as replicas of the authoritarian Ottoman example, rooting their power in the army and establishing a single-party regime. But whereas at the beginning of the twentieth century politics was driven by a global ideal of justice, a century later these parliaments come across as mere simulacra of popular sovereignty. Electoral practices for their part have been converted into instruments to legitimise the existing systems. Although economic development policies have been able to guarantee a degree of national stability – at the price of repressing discordant voices – these regimes have been discredited by economic difficulties and the rise of nepotism.

And so it is not surprising that the aspirations for political renewal expressed during the Arab Spring did not issue from established institutions but from outside official political circuits. The mass protests of unprecedented scale that drove the Arab Spring, though their long-term results are uncertain, show that ideas connected historically to the constitutional struggle still have the power to fire the political imagination. The rejection of corruption, insecurity, and arbitrary power, as well as calls for representation and justice continue to act as major vectors for political mobilisation. Above and beyond the repetitive sterile debates about the authoritarian culture of the Middle East or the compatibility of Islam and democracy, the future of politics resides in the ways the men and women concerned will reformulate, transform, and add to these vectors, and thereby develop new projects.

Notes

1

This work has been undertaken as part of the research project “Trans-acting Matters: Areas and Eras of a (post-)Ottoman Globalization”, funded by the French National Research Agency (ANR-12-GLOB-003).

2

Two recent works are: Elizabeth Thompson, Justice Interrupted. The Struggle for Constitutional Government in the Middle East, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2013; and Charles Kurzman, Democracy Denied, 1905-1915. Intellectuals and the Fate of Democracy, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2008.

3

Bernard Lewis, “Mashwara”, Encyclopedia of Islam, 2nd edition vol. 6, p. 724-725.

4

Linda T. Darling, A History of Social Justice and Political Power in the Middle East. The Circle of Justice from Mesopotamia to Globalization, London, Routledge, 2013.

5

Nicolas Vatin and Gilles Veinstein observe that between the regicide of Osman II (1618-1622) and the reign of Mahmud II (1808-1839), no fewer than half of the fourteen Ottoman sultans were deposed. Nicolas Vatin, Gilles Veinstein, Le Sérail ébranlé. Essai sur les morts, dépositions et avènements des sultans ottomans. xive-xixe siècle, Paris, Fayard, 2003, p. 63-64. See too: Baki Tezcan, The Second Ottoman Empire. Political and Social Transformation in the Early Modern World, New York, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

6

Carter Findley, “Madjlis al-Shura”, Encyclopedia of Islam, 2nd edition, vol. 5, p. 1082-1083.

7

Erdal Kaynar, “Occidentalisation”, in F. Georgeon, N. Vatin, G. Veinstein (eds.), Dictionnaire de l’Empire ottoman, Paris, Fayard, 2015, p. 871-873; Şerif Mardin, The Genesis of Young Ottoman Thought. A Study in the Modernization of Turkish Political Ideas, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1962, p. 177-180.

8

Niyazi Berkes, The Development of Secularism in Turkey, Montreal, McGill University Press, 1964, p. 90-91. The text may be consulted on the website of the Parliament of the Republic of Turkey, which is indicative of the importance attributed to the document (available online: https://www.tbmm.gov.tr/kultursanat/yayinlar/yayin001/001_00_004.pdf)

9

Butrus Abu Maneh, “The Islamic Roots of the Gülhane Rescript”, Welt des Islams, vol. 34, no. 2, 1994, p. 173-203; Frederick Anscombe, “Islam and the Age of Ottoman Reform”, Past and Present, n° 208, 2010, p. 158-199.

10

For the cheikh-ul-islam, the supreme Islamic religious authority in the Ottoman Empire, the declaration of the firman was a day of mourning and sorrow for Muslims, and the patriarch of the Greek Orthodox Church was offended at the idea that Greek Christians would now be equal to Jews, stating that he preferred the inequality prescribed by the Islamic hierarchy. See Şükrü Hanioğlu, A Brief History of the Late Ottoman Empire, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2008, p. 72-75.

11

Elizabeth Thompson, Justice Interrupted. The Struggle for Constitutional Government in the Middle East, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2013, p. 35-38

12

Arai Masami, “Citizen, Liberty and Equality in Late Ottoman Discourse”, in N. Clayer, E. Kaynar (eds.), Penser, agir et vivre dans l’Empire ottoman et en Turquie. Études réunies pour François Georgeon, Louvain, Peeters, 2013, p. 3-13; Şerif Mardin, The Genesis of Young Ottoman Thought. A Study in the Modernization of Turkish Political Ideas, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1962, p. 179-187.

13

It will be noted for instance that in the Mount Lebanon rural revolt of 1858-1860, the peasants called for equality and self-management, systematically expressed by reference to the 1856 imperial firman and the Tanzimat promises of freedom and equality. Ussama Makdisi, The Culture of Sectarianism. Community, History, and Violence in Nineteenth-Century Lebanon, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2000, p. 101-102; Elizabeth Thompson, Justice Interrupted. The Struggle for Constitutional Government in the Middle East, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2013, p. 61-76. For attempts to overthrow the sultan making use of the new language of the Tanzimat see Burak Onaran, Détrôner le sultan. Deux conjurations à l’époque des réformes ottomanes: Kuleli (1859) et Meslek (1867), Leuven/Paris, Peeters, 2013.

14

François Georgeon, Abdülhamid II. Le sultan-calife, Paris, Fayard, 2005, p. 64-65.

15

Robert H. Davison, Reform in the Ottoman Empire. 1856-1876, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1963, p. 388. Cf. Martin Kirsch, Monarch und Parlament im 19. Jahrhundert. Der monarchische Konstitutionalismus als europäischer Verfassungstyp, Göttingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1999, p. 27-35.

16

Cf. Hasan Kayalı, “Elections and the Electoral Process in the Ottoman Empire, 1876-1919”, International Journal of Middle East Studies, no. 27/3, 1995, p. 265-286.

17

Henry George Elliot, Some Revolutions and Other Diplomatic Experiences, London, John Murray, 1922, p. 252-253. Cf. Robert Devereux, The First Ottoman Constitutional Period. A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Press, 1963.

18

Bernhard Stern, Jungtürken und Verschwörer. Die innere Lage der Türkei unter Abdul Hamid II, Leipzig, Grübel & Sommerlatte, 1901, p. 153-158.

19

The khedive was the sovereign of Egypt, which at the time depended partially on the Ottoman Empire.

20

Nathan J. Brown, Constitutions in a Nonconstitutional World, Albany, State University of New York Press, 2002, p. 26-29.

21

Abdülhamit Kırmızı, “Authoritarianism and Constitutionalism Combined: Ahmed Midhat Efendi Between the Sultan and the Kanun-i Esasi”, in C. Herzog, M. Sharif (eds.), The First Ottoman Experiment in Democracy, Würzburg, Ergon, 2010, p. 53-65.

22

Cf. Charles Kurzman, Democracy Denied, 1905-1915. Intellectuals and the Fate of Democracy, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2008, p. 4-5.

23

Said A. Arjomand, “Islam and Constitutionalism since the Nineteenth Century: the Significance and Peculiarities of Iran”, in S. A. Arojomand (ed.), Constitutional Politics in the Middle East, London, Hart, 2008, p. 33-34.

24

For an overview, see François Georgeon (ed.), L’Ivresse de la liberté. La Révolution de 1908 dans l’Empire ottoman, Louvain, Peeters, 2012.

25

Bedross Der Matossian, Shattered Dreams of Revolution. From Liberty to Violence in the Late Ottoman Empire, Stanford, Stanford University Press, 2014.

26

Said A. Arjomand, “Islam and Constitutionalism since the Nineteenth Century: the Significance and Peculiarities of Iran”, in S. A. Arojomand (ed.), Constitutional Politics in the Middle East, London, Hart, 2008, p. 53.

Bibliographie

Butrus Abu Maneh, “The Islamic Roots of the Gülhane Rescript”, Welt des Islams, vol. 34, n° 2, 1994, p. 173-203.

Frederick Anscombe, “Islam and the Age of Ottoman Reform”, Past and Present, n° 208, 2010, p. 158-199.

Said A. Arjomand (dir.), Constitutional Politics in the Middle East, Londres, Hart, 2008.

Said A. Arjomand, “Islam and Constitutionalism since the Nineteenth Century: the Significance and Peculiarities of Iran”, in S. A. Arojomand (dir.), Constitutional Politics in the Middle East, Londres, Hart, 2008, p. 33-62.

Niyazi Berkes, The Development of Secularism in Turkey, Montreal, McGill University Press, 1964.

Nathan J. Brown, Constitutions in a Nonconstitutional World, Albany, State University of New York Press, 2002.

Linda T. Darling, A History of Social Justice and Political Power in the Middle East. The Circle of Justice from Mesopotamia to Globalization, Londres, Routledge, 2013.

Robert H. Davison, Reform in the Ottoman Empire. 1856-1876, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1963.

Robert Devereux, The First Ottoman Constitutional Period. A Study of the Midhat Constitution and Parliament, Baltimore, Johns Hopkins Press, 1963.

Henry George Elliot, Some Revolutions and Other Diplomatic Experiences, Londres, John Murray, 1922.

Carter Findley, “Madjlis al-Shura”, Encyclopedia of Islam, 2e édition, vol. 5, p. 1082-1083.

François Georgeon, Abdülhamid II. Le sultan-calife, Paris, Fayard, 2005.

François Georgeon (dir.), L’Ivresse de la liberté. La Révolution de 1908 dans l’Empire ottoman, Louvain, Peeters, 2012.

Şükrü Hanioğlu, A Brief History of the Late Ottoman Empire, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 2008.

Erdal Kaynar, “Occidentalisation”, in F. Georgeon, N. Vatin, G. Veinstein (dir.), Dictionnaire de l’Empire ottoman, Paris, Fayard, 2015, p. 871-873.

Hasan Kayalı, “Elections and the Electoral Process in the Ottoman Empire, 1876-1919”, International Journal of Middle East Studies, n° 27/3, 1995, p. 265-286.

Abdülhamit Kırmızı, “Authoritarianism and Constitutionalism Combined: Ahmed Midhat Efendi Between the Sultan and the Kanun-i Esasi”, in C. Herzog, M. Sharif (dir.), The First Ottoman Experiment in Democracy, Würzburg, Ergon, 2010, p. 53-65.

Martin Kirsch, Monarch und Parlament im 19. Jahrhundert. Der monarchische Konstitutionalismus als europäischer Verfassungstyp, Göttingen, Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht, 1999.

Charles Kurzman, Democracy Denied, 1905-1915. Intellectuals and the Fate of Democracy, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2008.

Bernard Lewis, “Mashwara”, Encyclopedia of Islam, 2e édition, vol. 6, 1991, p. 724-725.

Ussama Makdisi, The Culture of Sectarianism. Community, History, and Violence in Nineteenth-Century Lebanon, Berkeley, University of California Press, 2000.

Şerif Mardin, The Genesis of Young Ottoman Thought. A Study in the Modernization of Turkish Political Ideas, Princeton, Princeton University Press, 1962.

Arai Masami, “Citizen, Liberty and Equality in Late Ottoman Discourse”, in N. Clayer, E. Kaynar (dir.), Penser, agir et vivre dans l’Empire ottoman et en Turquie. Études réunies pour François Georgeon, Louvain, Peeters, 2013, p. 3-13.

Bedross Der Matossian, Shattered Dreams of Revolution. From Liberty to Violence in the Late Ottoman Empire, Stanford, Stanford University Press, 2014.

Nader Sohrabi, Revolution and Constitutionalism in the Ottoman Empire and Iran, Cambridge/New York, Cambridge University Press, 2011.

Bernhard Stern, Jungtürken und Verschwörer. Die innere Lage der Türkei unter Abdul Hamid II, Leipzig, Grübel & Sommerlatte, 1901.

Baki Tezcan, The Second Ottoman Empire. Political and Social Transformation in the Early Modern Word, New York, Cambridge University Press, 2010.

Elizabeth Thompson, Justice Interrupted. The Struggle for Constitutional Government in the Middle East, Cambridge, Harvard University Press, 2013.

Nicolas Vatin, Gilles Veinstein, Le Sérail ébranlé. Essai sur les morts, dépositions et avènements des sultans ottomans. XIVᵉ-XIXᵉ siècle, Paris, Fayard, 2003.