What have been the main environmental effects of the war in Donbas since 2014?

Prior to Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, there had been both direct (“physical”) and more “institutional” consequences of the war lingering in Donbas since 2014. Many of these consequences were analysed and summarised in several of our publications with the OSCE1. One can talk at length about repeated attacks on industrial facilities and critical infrastructure, including chemical plants, water treatment facilities and similar. Some of such incidents have resulted in spills of toxic chemicals, burning fuel tanks threatening people’s health and ecosystems. Other incidents were related to impeded access to facilities close to the “line of contact”, so that even regular situations could not be managed well (one example is the overflow of a livestock-waste storage south of Bakhmut in 2016). Cities and smaller settlements have been shelled or devoid of basic services, making water supply, wastewater treatment, waste management challenging if not impossible.

A widespread problem has been the gradual flooding of Donbas’s abundant coal mines: first due to electricity shortages, later by conscious decisions in areas not controlled by Ukraine. As a result, highly contaminated mine waters have gradually moved up, on their way polluting ground- and surface water supplies. Besides pollution, this is causing the waterlogging and deformation of the ground with potential long-term consequences for roads, pipelines, communications and buildings.

Valuable nature has been damaged in fighting, with fortifications built in protected areas, forests abused for cover, and animals scared and killed by shelling, mines and unexploded munitions. Some of the protected areas like the Meotida national park were separated by the “line of contact” and could no longer be managed as single entities. Wildfires in the areas of fighting in 2015 were 2-3 times more frequent than in the adjacent regions with a similar weather; this was both due to high-temperature impacts, and to the difficulties of putting down fires near frontlines.

The integrity of the region’s environmental monitoring system, once among the most advanced in Ukraine, has suffered too. Ukraine’s government has lost access to large parts of the monitoring network and environmental data, and it has not been known with any certainty how much monitoring has continued in those areas.

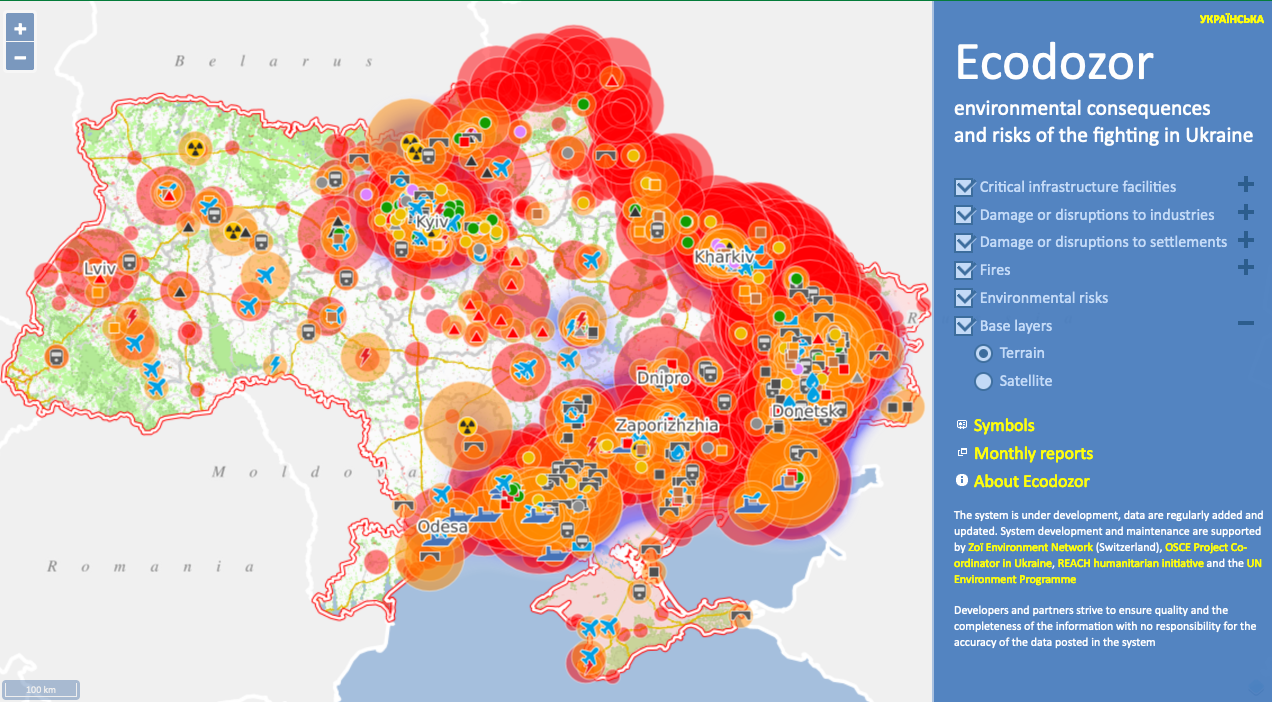

Environmental consequences and risks of the war in Ukraine.

How does Zoï Environment Network work? What contacts do you have with environmentalists in Ukraine?

We have a long history of cooperation with Ukraine, its authorities and the environmental community. Already before Zoï officially came into being in 2009, we helped the UN and the OSCE expand Ukraine’s environmental information and assessment capacities. Part of that work included assessing environment-security linkages and “hot-spots” with a wide range of Ukraine’s organisations and experts. As the “hot-spots” included Crimea and Donbas, we have worked with experts and organisations there on specific environmental concerns such as coal mining, as well as helped promote collect and broadly disseminate environmental information. In later years we were part of the European effort at developing a Shared Environmental Information System in Ukraine and the entire EU’s Eastern Neighbourhood region, as well as supported the OSCE with assessing the environmental impacts of the war in Donbas described above. The results of all this work, the contacts and networks have helped us continue our support to Ukraine today.

How can we access valuable information (data) on these issues? Which institutions produce data from the field?

Access to data is never easy, certainly not at the time of war. In our work we use much open sources, above all traditional and social media as well as the available official information. Governmental agencies certainly collect environmental data, and share them to the extent they see possible given the precarious situation. Certainly, like before in Donbas, a part of monitoring capacities has unfortunately been lost or activities have been temporarily scaled down. Some of the obtained data are not shared being part of ongoing criminal investigations of environmental damage. Non-governmental and international organisations monitor the environmental side of the war too, among other sources relying on satellite data and citizen science. Growing cooperation among all these players strengthens the common factual base. Still, much of the data accessible today are of a secondary or remote nature. The amount of first-hand information coming directly from the field, in particular closer to frontlines, remains extremely limited, while field access to liberated areas is difficult due to widespread mining and unexploded ordnance.

How has the war since February affected the environment on the territory of Ukraine? What distinguishes this conflict from past wars from an ecological point of view?

This is the question we are frequently asked. One perspective is that we see today all over Ukraine what we have seen in Donbas since 2014, but on a much larger and more brutal scale. This is a modern war in a highly industrialised and urbanised country, with widespread damage from military activities, and continuous attacks on cities and civilian infrastructure, also affecting lands and nature. Looking back at experiences with WWI and WWII, cleaning up the already accumulated environmental remnants of this war may take decades if not centuries. This war is also unique by being waged in a country with 15 operational reactors at 4 nuclear power plants, including the largest in Europe Zaporizhzhia NPP, and with the site of the biggest nuclear disaster the world has seen to-date at Chornobyl. The risk of a new nuclear disaster – whether intentional or accidental – unfortunately remains high.

But in addition to the scale and the brutality of the warfare and its impacts, one difference from past conflicts may somewhat paradoxically be in the much broader and stronger awareness of its environmental effects. Much owing to the recognition and broadcasting of them by Ukraine, media attention to this aspect of the war has been unprecedented, and so has been the concerted effort of various organisations working in this field. Hopefully this will make a difference to post-war justice for the aggressor and to Ukraine’s reconstruction and recovery agenda.

Does the growing international concern for environmental issues play a role in Kyiv's policies during the war?

From the very beginning of the war, Ukraine has continuously brought up its environmental dimension to the attention of the world. This was much due to the efforts of the Ministry of Environment Protection and Natural Resources as well as many environmental NGOs. President Zelensky’s “peace formula” presented at the G20 summit in November 2022 included among its 10 points putting an end to Russia’s ecocide and the need for the immediate protection of the environment. Sustainability is also one of the eight principles included in the Lugano Declaration, a political framework for reconstruction in Ukraine agreed in July 2022. This stand by Ukraine has certainly been reinforced by attention among international organisations, the civil society, the expert community and it he media. The United Nations, the OSCE, the EU have all made repeated statements on this topic and have systematically pursued the environmental dimension in their support to Ukraine. This trend needs to continue and strengthen once the war ends and the recovery begins.